1949–53

The dropping of the atomic bombs on Japan had a dual purpose: force the Japanese government into an early surrender and intimidate the Soviets and make them, in the words of Secretary of State James Byrnes, ‘more manageable’ when discussing the post-war world (Burr and Kimball 2015: 12). The dominant US position led to the practice of nuclear threat diplomacy. Nuclear weapons were deployed, their use was threatened and nuclear alerts were carried out to coerce adversaries into concessions or to cease activities which were judged inimical to US interests. Hence nuclear policy was both a deterrent strategy but also one to coerce and intimidate.

The US administration concluded that in order to ensure its continued wellbeing, no adversary or coalition of adversaries could be allowed to dominate Europe and Asia. This led to the policy of establishing foreign bases worldwide to cope with military threats and the risk of being cut off from raw materials and foreign markets. It was natural to conclude that the Soviet Union was becoming the greatest military threat to American power. Despite the fact that President Truman abhorred the use of nuclear weapons because of their indiscriminate destruction of military targets and civilians, he and his military advisers set out to ensure that the US was capable of waging a nuclear war successfully. It was thought that the threat of conventional or nuclear bombing would undermine the enemy’s resolve and thereby secure victory. Immediately after the nuclear attack on Japan, the air force was thinking of forming a group which could drop atomic bombs on any part of the planet and, as a result, the Strategic Air Command (SAC) was set up in March 1946. A secret agreement with the Royal Air Force to construct nuclear storage sites at two air bases was concluded. SAC assumed the key role in US nuclear thinking, but by the end of 1947 there were only eighteen B-29s capable of carrying nuclear bombs and only thirteen bombs which could be used. By late 1948, there were thirty B-29s and fifty-six bombs available, but this was far short of the 200 needed to destroy key Soviet targets. During the Berlin blockade, bombers were based in West Germany and England but were not capable of carrying atomic bombs, and it was a game of bluff as the Soviets could not be sure that atomic weapons would not be used. The Berlin crisis also led President Truman to agree to the use of nuclear weapons in the first instance, as he concluded that deploying sufficient conventional armed forces would be prohibitively expensive and would ruin the US economy (Burr and Kimball 2015: 13–17).

Scientists and politicians wrestled with the problem of what would happen when the Soviet Union developed its own atomic bomb. Bertrand Russell, the famous British mathematician, advocated a nuclear strike against the Soviets in October 1946, and by 1948 he was proposing a preventive war to eliminate a Soviet nuclear threat. John von Neumann, the founder of game theory and a leading nuclear scientist, in 1950, said: ‘If you say bomb them tomorrow, I say why not today? If you say today at five o’clock, I say why not one o’clock?’ (Trachtenberg 1991: 104). George Kennan, in June 1950, commented that a war with the Soviet Union before it had built up its nuclear arsenal might, in the long term, ‘be the best solution for us’ (Trachtenberg 1991: 103). Charles Bohlen, of the State Department, also ruminated about what Americans might think in the future about not acting in the present.

The Berlin Blockade was the first time since 1945 that a military conflict between the Soviet Union and the West could have erupted. Washington had a plan for a preventive war (First Strike), with thirty-four atomic bombs being dropped on twenty-four Soviet cities if the crisis escalated. The atomic First Strike would provide the time to mobilise conventional forces. On 10 May 1949, the blockade was lifted by Moscow and the crisis passed but it had major ramifications. The danger from the East led to the formation of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) on 4 April 1949. Truman regarded it as a ‘gamble’, and George F. Kennan and Charles Bohlen believed it to be a mistake. Would it get through Congress? It did with an overwhelming majority, as Stalin had frightened the Americans into guaranteeing the security of the Western Europeans.

With the blockade over, the West attempted to overturn communism in Albania in December 1949. It was a disaster because Kim Philby, a Soviet agent in British intelligence, then in Washington, revealed what was being planned. The explosion of the Soviet atomic bomb in August 1949 ended any hopes of military action to remove a communist regime. The bomb also demonstrated the inadequacy of US military planning which had assumed that its nuclear monopoly protected it against a Soviet conventional attack. Washington now had to spend to bring its conventional forces up to the levels of the Soviet. This was not popular, and Truman still hoped for some accommodation with Moscow, but the war in Korea ended such dreams. NSC-68 was the result and it envisaged a massive increase in defence spending. This led President Truman to lament on 9 December 1950: ‘I have worked for peace for five years and six months and it looks like World War III is near. I hope not.’

The Korean War was the first time that the use of nuclear weapons was seriously considered. Washington incorrectly concluded that the North Koreans had initiated the conflict without consulting Moscow and worried that the latter might intervene. The Americans hesitated to use nuclear weapons against another Asian nation, but the entry of China changed the situation. President Truman, on 30 November 1950, stated that the US would deploy ‘every weapon we have’ against Chinese and North Korean civilian and military targets. Worldwide opposition forced him to retract his words and declare that the atomic bomb would not be used. Nine atomic bombs were deployed in Guam, but the North Koreans and Chinese paid no attention. As a result, the president gave up threatening a nuclear strike because the enemy did not believe him.

President Eisenhower and Secretary of State John Foster Dulles had no such qualms about the use of nuclear weapons, and it became integral to their military thinking as they regarded the atomic bomb as just another weapon. Control of nuclear weapons passed from the Atomic Energy Agency to the Department of Defense in April 1953. The president came to believe that his threat to use nuclear weapons had played a ‘decisive part in terminating the Korean War’ (Burr and Kimball 2015: 22). This is almost certainly incorrect, but that is irrelevant because the president believed it, and it strengthened his conviction that nuclear threats were an effective way of conducting diplomacy.

In February 1949, the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) took Beijing, and in October it secured the last remaining key city in the south, Guangzhou. Chiang Kai-shek’s only option was to decamp to Taiwan.

So why did Mao defeat Chiang? Even in 1949 Chiang had more troops than Mao. Chiang, in Taiwan, analysed the reasons for his defeat. The Guomindang or Nationalists had not learnt enough from Mao. ‘Disdaining the dialectic was the reason why we lost,’ mused Chiang. The Guomindang should have adopted democratic centralism, set up a youth movement and made workplace cells the basic building block of the party. The Leninist model was thus superior to the American model of democracy and a liberal market economy. Mao found it astonishing that the US military did not intervene to save the Nationalists. The communist tactic of unleashing a class war in the countryside (ironically pioneered by the Nationalists) was a great success. The Guomindang could never control inflation. This can be illustrated by the following: in 1940, 100 yuan bought a pig; in 1943 a chicken; in 1945 a fish; in 1946 an egg; and in 1947 one third of a box of matches. Neither could corruption be tamed.

Just before the People’s Republic came into being, Mao outlined three major goals: set out a separate stove; put our house in order before inviting guests; and one-sidedly follow the Soviet Union. The first two goals implied that the task was to remove the influence and impact of imperialism in China. A long list of imperialists had ruled China. The Jin and Yuan dynasties ruled from 1115 to 1368. A Han Chinese dynasty, the Ming, took over from 1368 to 1644. Then China again succumbed to foreign rule, the Manchu Qing dynasty lasting until 1911. Hence over the previous thousand years, a Han Chinese dynasty only ruled for about a quarter of this period. Britain, the US, Russia, Italy, Germany, Portugal, France and Japan had all occupied parts of China. The years between 1839 and 1949 are known in China as the ‘century of humiliation’. Soon the Soviet Union was to join the league of imperialists. For Mao, it was time the Han Chinese took control of their destiny. The third goal allowed China to join the communist commonwealth and hence the world of the future.

The People’s Republic of China was proclaimed by Mao Zedong in Tiananmen Square on 1 October 1949. Why was 1 October chosen and not 25 September, for instance? The Qing dynasty was toppled in October 1911 and the Bolsheviks seized power during October, so October had symbolic significance. The new national flag was red or communist but also identified with China’s red earth. The four yellow stars which surrounded the larger star in the left-hand corner represented the national unity of the classes in society: the bourgeoisie, the petit bourgeoisie, the workers and peasants. The new order in China would be communist, nationalist and pro-peasant.

Mao declared that China was no longer ‘on its knees’ and it would stop kowtowing before foreigners. The task was to destroy the old world and create a new one. China had accounted for 30 per cent of the world gross domestic product (GDP) as late as 1820 – an amount greater than the GDP of Europe and the US combined – and was still the largest world economy in 1860.

Taking power was a stupendous achievement and modernisation would now follow a communist and not a capitalist model, but Mao had no understanding of economics, at least in the sense of raising living standards. The goal was to make China militarily strong enough to be able to stand on its own feet. The ‘century of humiliation’ had come to an end, and henceforth China would seek to develop in a way which corresponded to Chinese characteristics. Foreigners, first and foremost the Soviet Union, still possessed concessions on Chinese soil, and persuading them to leave was an important task.

China, economically, was in a poor state with the vast majority of the population below the poverty line. Investment and know-how would mainly have to come from one source: the Soviet Union. Capitalism had not industrialised China, and in 1952 industrial output accounted for less than 3 per cent of GDP. The state would now industrialise the country, but American capital and expertise would not be accepted.

In order to gain the maximum advantage from the Soviet connection, Mao had to be obsequious to Stalin. He had played this game during the 1930s when he knew that the vozhd could have removed him with a flick of his finger. The Stalinist model was de rigueur if he wanted the boss’s support. In the early stages – until the mid-1950s – it was the Leninist model which was more relevant:

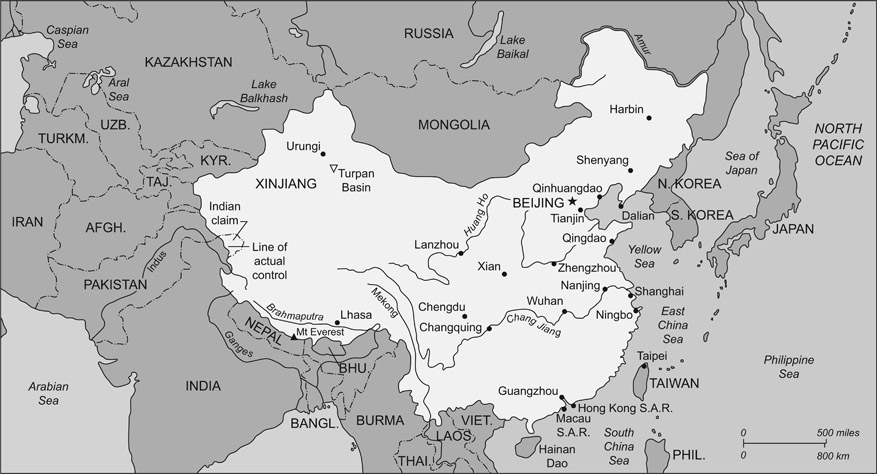

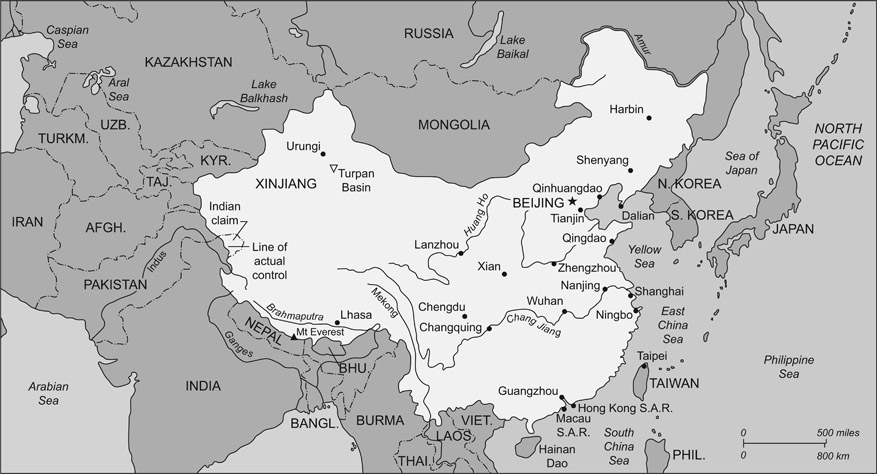

Map 2.1 The People’s Republic of China

a single dominant party claiming the monopoly of power; democratic centralism to ensure a power vertical; a ruling bureaucracy; a cadre party where iron discipline was enforced; the ruthless use of terror to eliminate opposition in the party and outside; a powerful secret police to strike fear into opponents; a military devoted to the party; the commanding heights of the economy in state hands; state control of foreign trade; and predominantly private agriculture with market prices being regulated by the state. Lenin had provided a master plan of how to take and keep power, but Mao pretended that he had learnt it all from Stalin.

Mao’s problem was that Stalin had no intention of developing China into a state which could challenge the hegemony of the Soviet Union in the communist world. The risk for Moscow was that China, not the Soviet Union, would become the beacon of hope for Asia and the developing world. Mao could turn into an even more formidable Tito. Hence the master’s first priority was Soviet security.

Mao kept on asking for permission to visit Moscow but Stalin kept him at arm’s length. On 26 April 1948, Stalin agreed that Mao could come to Moscow but retracted his invitation on 10 May. On 4 July 1948, he informed the vozhd that he was about to leave Harbin and fly to the Soviet capital. A reply came ten days later, but he was told that because of the harvest, leading comrades would leave in August and remain away until November, so the end of November would be an appropriate time for the Chinese leader to come to Moscow (Mao saw through this flimsy excuse). Mao informed Stalin that his bags had been packed, leather shoes acquired and a thick woollen coat made, and he kept on asking for an invitation. On 28 September 1948, he wrote that on a ‘series of questions it is necessary to report personally to the Central Committee and the glavny khozyain (big boss)’. Stalin agreed he could come in late November, but the visit was postponed, and on 14 January 1949 Stalin again suggested Mao postpone his trip. Anastas Mikoyan, the vozhd’s diplomat for all seasons, was dispatched to tell Mao that such a visit would be understood in the West as one to receive instructions. This ‘would lead to a loss of prestige for the Communist Party of China (CPC) and would be used by the imperialists and the Chiang Kai-shek clique against the Chinese communists’.

Mikoyan stayed in China from 30 January to 8 February 1949. The talks were wide-ranging and Mao went out of his way to portray himself as a ‘humble student of Stalin’. Mikoyan viewed the Chinese revolution as an event of worldwide importance and believed that the CPC’s experience enriched Marxism. Mao asked for military aid, a loan of $300 million and Soviet specialists to help run the country. Mikoyan advised the nationalisation of Japanese, British and French but not American property. Mao wanted Outer Mongolia to unite with Inner Mongolia (which was part of China) but Mikoyan retorted that Outer Mongolia was already independent. If they did unite in the future, they would form an independent state. Moscow regarded the 1945 Sino-Soviet Treaty as an unequal one and was willing to withdraw its forces from Port Arthur, but the Changchun Railway, on the other hand, had been built with Russian money and was therefore not part of the unequal treaty.

In August 1945, Chiang Kai-shek, the Guomindang leader, had been forced by the US to sign a thirty-year Sino-Soviet Treaty of Friendship and Alliance, along with other agreements. These stemmed from accords reached at the Yalta conference in February 1945, which awarded the Soviet Union territories lost as a result of the Russo-Japanese War of 1904–5. The Chinese Changchun Railway would be jointly owned and operated by China and the USSR; Outer Mongolia was recognised as a Soviet satellite and it became the People’s Republic of Mongolia; the Port Arthur naval base was to be jointly used by China and the Soviet Union; and a long-term lease on the port of Dalian was agreed. In return, Stalin recognised Chiang as the leader of China and advised the CPC to submit to him. The geopolitical aim of reclaiming all that Tsarist Russia had lost in north east China took precedence over supporting the CPC, and the latter was advised not to expect Soviet assistance in its struggle for power. In June 1948, a request for arms to launch an attack in Manchuria was turned down by Moscow. However, the Soviet Union stepped up economic aid, including restoring railway lines and building bridges. The CPC supported the expulsion of Yugoslavia from the Cominform.

A CPC delegation, led by Liu Shaoqi, arrived in the Soviet Union on 26 June 1949 and left on 14 August. This was the first high-level delegation to the Soviet Union since Mao had achieved supremacy in the CPC. In late June, Mao declared that the CPC’s policy of ‘leaning to one side’ (the Soviet Union) while Liu was in Moscow (actually he had decided on this policy a year earlier). The political base for the alliance was being laid.

The Chinese would get a $300 million loan at 1 per cent interest, and the first group of specialists were ready to leave for China. Stalin hoped the CPC would accept more responsibility for assisting national democratic movements in colonial and semi-colonial states since the Chinese revolutionary experience would be highly relevant to these countries. The boss proposed a division of labour: China would concentrate on the East and the Soviet Union on the West. Despite these fine words, the Korean War was to demonstrate that Stalin had no intention of affording China primacy in Asia. The USSR would assist China in constructing an army, air force and navy, but Stalin made clear that he would not support an attack on Taiwan as it could trigger a Third World War. In May and June 1949, a US diplomat discussed US-China relations with a senior communist official. Nothing came of these talks as Mao had already decided to side with the Soviet Union (Shen and Xia 2015: 11–37).

In the euphoric days after the founding of the People’s Republic, Mao waited for the invitation of invitations: a summons from the vozhd. None came and so on 8 November he sent a telegram saying he would like to come and would put the Sino-Soviet Treaty of 1945 at the top of his agenda. Zhou Enlai, now number three in the party hierarchy and foreign minister, was dispatched to tell the Soviet ambassador that Mao would like to pay his respects to Stalin on his seventieth birthday, on 21 December 1949. He was thinking of spending four months away – one month negotiating a new Sino-Soviet treaty with Stalin, two months in Eastern Europe and a month relaxing at a Soviet spa. Stalin grudgingly agreed but made clear it was not to be a state visit. Mao would be visiting Moscow as one of a group of communist leaders all cackling about how wonderful the master was. Mao left Beijing on 6 December 1949 by train and arrived in Moscow ten days later. The station clock dramatically struck twelve as he arrived, but Mao did not take with him his number two (Liu Shaoqi) or his number three (Zhou Enlai). He was greeted by Molotov and Bulganin, the latter resplendent in his marshal’s uniform. Stalin received Mao in his Kremlin office later that evening, but when he met Stalin, Mao excluded his own ambassador as he expected to be humiliated and wanted to ensure that no one witnessed his discomfort.

The brief Stalin received described Mao as

unhurried, even slow … He moves steadily towards any goal he sets, but not always follows a set path, often with detours … is a natural performer; is able to hide his feelings and can play whatever role is needed.

The Chinese leadership referred to Stalin as the ‘old man’. During the first meeting Mao did not present a list of demands. He just requested advice and listened attentively to the Boss’s remarks. Responding to Mao’s question about the Sino-Soviet agreement, Stalin made clear that he preferred to retain the accord but was willing to make concessions in favour of the People’s Republic. Annulling it could permit ‘England and America’ to reconsider the treaty’s provisions awarding the Kurile Islands and southern Sakhalin Island to the USSR. Mao did not see through this obfuscation at the time but he did later. Stalin said that aid would be extended to the infant state, but Mao had not achieved his main objective, annulling the Sino-Soviet agreement; this would have to wait until later. Stalin even said that Mao’s collected writings would be published in Russian.

Mao was ensconced in a dacha – bugged, of course – about 30 km from Moscow. All he could do was fume and look out at the snow. A succession of minions came to see him, and their task was to draw up a psychological portrait of the new Chinese Emperor. Mao complained about the food and the bed, but every now and then he was given a little treat. On one occasion he was taken to a collective farm to gaze at some cows. He was keen to meet other communist leaders but Stalin ensured he only met the Hungarian chief. On 21 December, he was seated on Stalin’s right at the birthday festivities in the Bolshoi Theatre and was the first foreign guest to speak. The audience roared: ‘Stalin, Mao Zedong!’ Mao responded with: ‘Long live Stalin, Glory to Stalin.’ The Hungarian Party leader thought the ovation reached heights that the Bolshoi had seldom experienced. Then Mao returned to his dacha. He became so frustrated that he shouted at one of Stalin’s aides that he had come to Moscow to negotiate not to ‘eat, shit and sleep’ and talked about returning to China a month early.

Mao met Stalin on 24 December, but the vozhd would not discuss another pet theme: the arms industry. Further, Mao’s birthday on 26 December was ignored. Mao then decided to call Stalin’s bluff. He shouted – in order to ensure it was heard – that he was ready to do business with the US, Britain and Japan. Diplomatic relations were established with London on 6 January 1950, and a rumour was leaked to the British press that Stalin was holding Mao under house arrest. Stalin engaged in a volte-face and began to negotiate seriously. Zhou Enlai and other officials were summoned to Moscow but they were instructed to take their time and come by train.

Only on 22 January 1950 did talks between Stalin and Mao and his team get under way – in the boss’s Kremlin office. A Sino-Soviet Treaty of Friendship, Alliance and Mutual Assistance was agreed on 14 February 1950 and various other agreements were also signed. The Soviet Union lost almost all the gains it had achieved at Yalta and in the Sino-Soviet treaty. The Changchun Railway and Port Arthur, instead of passing to the USSR for thirty years, were to be returned by 1952. Property leased in Dalian was to be returned to China immediately and thereby the USSR lost its only ice-free port on the Pacific. The People’s Republic renounced all claims on Outer Mongolia. A $300 million loan was extended, at 1 per cent interest, over five years, and to go on defence. The Soviet Union would begin building fifty large industrial projects and in return, Mao conceded – through gritted teeth – that Manchuria and Xinjiang were Soviet spheres of influence. The Soviets were to exploit their industrial and raw material wealth and Moscow also had the right to acquire ‘surplus’ tungsten, tin and antimony for fourteen years. This prevented China from selling these valuable products on the world market for dollars until the mid-1960s. Deng Xiaoping told Mikhail Gorbachev, in 1989, that of all the unequal treaties signed with Tsarist Russia and the Soviet Union, this was the most painful. China not only had to pay the wages of Soviet engineers – often ten times what a Chinese engineer earned – but had to compensate their home enterprises for the loss of their labour as all Soviet citizens were outside Chinese jurisdiction. This was reminiscent of the days of European imperialism, but the Soviet Union did agree to a treaty guaranteeing to intervene if China were attacked by Japan or its allies, in particular the US. At the signing ceremony, Stalin warned Mao that any leader who imitated Tito would soon be replaced.

Mao told Stalin that the People’s Republic needed up to five years to consolidate and restore the economy. How many years of international peace would prevail? Stalin was very optimistic and pointed out that Japan and the US would not invade China. Peace might even last twenty-five years or even longer, so a military alliance between the two countries was not needed.

Stalin did pay his respects at a reception at the Metropol Hotel on the evening of 14 December to mark the signing of the treaty. He wanted it to be held in the Kremlin, but Mao demurred and eventually Stalin gave in. A handwritten invitation arrived addressed to Stalin and his wife, and this revealed that the Chinese knew nothing of the vozhd’s private life. As was customary, there were lots of toasts proposed and responded to. Stalin hosted a farewell luncheon on 16 February, and the Chinese delegation left the next day by train (Khlevniuk 2015: 288–93).

Throughout the negotiations Stalin addressed Mao as Gospodin (Mr.) and refused to call him comrade. This was deeply insulting to the Great Helmsman and revealed that the vozhd was not certain that he was a communist. He even referred to him as a ‘margarine’ communist.

So why did Stalin make so many concessions to Mao? He was wary of China going its own way and Mao turning into another Tito, and Sino-American relations might develop in a manner inimical to Soviet interests. He abandoned his strategic interests in north east China, but it occurred to him that there were ice-free ports and naval facilities in Korea.

In 1945, Korea was divided along the 38th parallel. Japanese forces surrendered to the Red Army in the North and to the Americans in the South. In the North, the Soviets installed a thirty-three-year-old Red Army officer, Kim Il-sung (literally ‘Become the Sun Kim’), and in the South, the Americans installed a seventy-year-old professor, Syngman Rhee, who had spent thirty-three years in exile in the US. Skirmishes between North and South were the order of the day, and both sides concluded that the only way to reunite Korea was by military force. Stalin was cautious and his instructions to Soviet representatives in the North, in May 1947, were: ‘We should not meddle too deeply in Korean affairs.’

Kim Il-sung visited Moscow in March 1949 to ask for help in taking over South Korea but Stalin declined. He kept Kim in check until he had the atomic bomb, the communists had taken over China, and Korean units fighting with the Chinese Red Army – amounting to about 50,000 troops with their weapons – had returned to North Korea. To increase the pressure on the vozhd, Kim even hinted of reorienting his country’s policy towards China. Only the Soviet Union could provide the North with weapons, and the Chinese were also dependent on Soviet military assistance. Perhaps reverses in Western Europe could be compensated for in the East. Soviet occupation forces began to leave North Korea in late 1948, and US forces left South Korea in June 1949.

On 12 January 1950, Dean Acheson, US secretary of state, articulated a new Asia policy as Washington was washing its hands of Chiang Kai-shek’s Guomindang. On 30 December 1949, the National Security Council had concluded that the ‘strategic importance of Formosa [Taiwan] does not justify overt military action’, and President Truman made it clear that the US would not extend military aid to Chiang. Acheson then went on to state that the greatest threat to the People’s Republic was the Soviet Union which was detaching Outer Mongolia, Inner Mongolia, Manchuria and Xinjiang from China and annexing them to the Soviet Union. He also stated that the integrity of China was in America’s national interest irrespective of China’s communist ideology. The secretary of state was, in fact, proposing a new Sino-American relationship (Kissinger 2012: 119–20). Stalin reacted as if stung – Acheson’s intention – and sent foreign minister Andrei Vyshinsky and Vyacheslav Molotov to inform Mao and ask for a rebuttal of the Acheson ‘slander’, but Mao merely asked Xinhua, the Chinese news agency, to publish a rebuttal. Acheson went on to define the US military defence perimeter in the Far East. It ran from the Aleutians through Japan and the Philippines. South Korea and Taiwan were not mentioned, nor was Vietnam. This was not an innovation as he was merely reiterating what General Douglas MacArthur had stated in March 1949. The Soviet ambassador in Pyongyang sent a telegram about Acheson’s speech and reported that Kim Il-sung had asked repeatedly for a meeting with Stalin to discuss the reunification of Korea. In September 1949, the Soviet Politburo had expressly prohibited the North Koreans from engaging in any military measures near the 38th parallel. On 30 January 1950, Stalin changed his mind saying he would talk to Kim Il-sung. If North Korea won the war the whole of Korea would fall under Soviet control. If it lost the war, the situation would be so tense that the Chinese would request that Soviet troops remain in Port Arthur and Dalian.

Kim flew to Beijing, on 13 May 1950, to report on his talks with Stalin, reporting that the Soviet leader had approved his plans to attack the South. Mao wondered if the US would intervene, but Kim thought that even if it did, the North would have occupied the South beforehand. Mao offered to deploy three armies along the Sino-Korean border, but Kim waved this aside saying his own forces did not need any help (Chen 1994: 112). Mao asked Zhou Enlai to cable Moscow and seek Stalin’s confirmation of Kim’s narrative. The vozhd replied that the decision to go to war was to be taken by China and North Korea, but if there was disagreement, they should postpone the attack. Kim returned to Pyongyang on 16 May with Mao’s support for war – or at least this is what he told Stalin. Stalin did not think the US would intervene but he was wrong, and so were US policymakers who believed that China would not intervene. Mao saw the US intervention in South Korea as an act of war against Asia and it was thus inevitable that China would join the war sooner or later. What was Mao’s objective and why did he intervene when he did?

Mao’s goal was a pre-emptive strike to take US military planners by surprise and thereby sow confusion about China’s intentions. China saw very quickly that North Korea would lose the military conflict and set about preventing this. Chinese strategy normally exhibits three characteristics: meticulous analysis of long-term trends; careful study of tactical options; and detached exploration of operational decisions (Kissinger 2012: 135). The Chinese had intended to invade Taiwan just before the Korean War but the US fleet prevented this. They could then switch these troops – over 250,000 – to the Sino–North Korean border, and these moves were in place even when the North was winning in the South. The Chinese military believed it could defeat the Americans, who they calculated could only deploy half a million soldiers while the PLA could muster four million. China also had logistical advantage and they calculated that most of the world would support them. A nuclear attack was discounted. Zhou Enlai thought that if the US won in Korea it would move against Vietnam, so it had to be blocked in Korea.

On 25 June 1950, the North Koreans crossed the 38th parallel and initially were unstoppable. The Americans acted immediately as they regarded the offensive as a plan to expand communist influence which would eventually embrace Europe. The Americans managed to get a UN mandate from the Security Council; this was possible because the Soviet delegate had been boycotting the UN Security Council. A UN coalition, including US, Britain, Turkey and twelve other nations, turned the tide. The Northern gamble to take over the South before large numbers of American troops arrived failed, but despite taking most of South Korea by September the communists could not administer the killer blow. MacArthur invaded at Inchon (predicted by the Chinese) and crossed into North Korea, took Pyongyang and most of the North, and it appeared the Americans would sweep Kim Il-sung into the sea.

On 1 October, Stalin requested that Chinese volunteers dressed in North Korean uniforms intervene north of the 38th parallel, but he remarked he had not informed the North Koreans of this. The vozhd was willing to pledge military support and, if there was going to be a major international war, it would be better to fight it now before Japan recovered its military might. Was Stalin serious about launching a war against the US? No. The balance of forces was still against the USSR, and Stalin’s aim was to tie US forces down in Korea and prevent a US-dominated Korea and Japan emerging as a ‘new’ NATO in East Asia.

On 11 October, Zhou Enlai and Lin Biao – who had refused command of the North East Border Defence Army – arrived at Stalin’s villa on the Black Sea. Zhou and Lin had orders to inform Stalin that without Soviet supplies, China might not commit itself to the planned invasion. The vozhd made it clear that the Soviet air force was not ready to provide air cover for invading Chinese troops. On 13 October, Stalin told Kim:

We feel that continuing resistance is pointless. The Chinese comrades are refusing to take part militarily. Under these circumstances you must prepare to withdraw all troops and military hardware. Draw up a detailed plan of action and follow it rigorously. The potential for fighting the enemy in the future must be preserved.

(Khlevniuk 2015: 296)

Stalin proposed that Kim set up a Korean government in exile in Manchuria, something which was bound to annoy Mao. The Soviets informed the Americans that if General Douglas MacArthur halted at the 38th parallel, they would convince the North Koreans to cease fighting and agree to a UN delegation entering to organise a general election.

On 18 October 1950, over 180,000 Chinese troops crossed into Korea under night cover and took UN forces completely by surprise, obliging them to retreat. It has been called the greatest ambush in modern warfare. The Soviet air force would defend Manchurian airspace but not Korean. On 1 November, the Soviet air force took part in a battle over the Yalu River (the border between China and North Korea). On the same day, MiG fighters shot down two F-82 planes and anti-aircraft guns another two, but the Soviet side suffered no losses. Peace negotiations could have begun after the Chinese defeated the UN forces in North Korea, but Mao did not want peace. The coalition defeat underlined the catastrophic misjudgement of Chinese military potential by General MacArthur. The Chinese took Seoul, the South Korean capital, in early 1951, but the South counterattacked and it appeared no side would win.

Kim asked Mao for a ceasefire in June 1951, but China wanted the war to wear down the Americans and their allies. The longer the war lasted the more arms factories he could ask for from Moscow. In February 1953, the new US president, Dwight D. Eisenhower, warned China he might use the atomic bomb; this was great news for Mao, so he asked Stalin for an atomic bomb. On 28 February 1953, Stalin decided that the war had to end, and on 5 March 1953 he was dead.

Mao did not bother to go to the funeral and Zhou Enlai went instead. He then moved into Eastern Europe. Harry Pollitt, the chief of the Communist Party of Great Britain, asked him for a $5,500 donation to refurbish Marx’s grave in Highgate Cemetery, in London. The Chinese had better things to do with their money.

An armistice was signed on 27 July 1953. China sent three million men into Korea and lost about 400,000 and the coalition counted 142,000 dead including 30,000 Americans. The Soviet air force won the air war, and twelve Soviet air divisions were deployed with 72,000 airmen involved in combat. The Soviets claimed they shot down 1,097 enemy planes and anti-aircraft guns accounted for another 212, with the Soviets losing 335 planes and 120 pilots. Among the dead was Mao’s eldest son. Moscow provided the Chinese with hundreds of MiG warplanes.

The war came at an inappropriate time for China as it needed all its resources to develop the country. There was also the risk that war could lead to greater internal opposition, but it also permitted Mao Zedong Thought to be emphasised, with the Americans – and by extension capitalism – clearly the enemy. Widespread purges were carried out during the Korean War and as many as five million may have been executed. The Korean War resulted in forced grain requisitions, and millions starved as grain was taken by force to feed the military. However, on balance, it was a great victory for Mao and the People’s Republic as, for the first time in a century, China had come out of a war victorious and this swelled national pride. The communists could now boast that they could defend the motherland against any foreign devil and, as a result, Mao’s prestige reached a record high.

Between 1950 and 1953, China imported technical equipment worth 470 billion roubles, or 69 per cent of what had been ordered; this permitted the construction of forty-seven industrial projects. The 19th Congress of the All-Union Communist Party (Bolsheviks) – it was renamed the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU) at the Congress – in October 1952 increased the assistance. Over the years 1950 to 1953, 1,093 technical experts worked in China, and the number involved with Chinese projects in the USSR rose by 30,000. The Soviets designed about 80 per cent of all projects, provided 80 per cent of the equipment and provided technical materials free of charge. Over the same period, Moscow sent 120,000 books and reference materials and 3,000 scientific documents free of charge. Thousands of Chinese students and specialists went to the Soviet Union to study. The Soviets, therefore, provided the science and technology base which permitted the Middle Kingdom to industrialise rapidly (Shen and Xia 2015: 89–90).

The war poisoned Sino-American relations for almost two decades, and it ensured that Beijing had to look to Moscow for support. Just after the outbreak of the Korean War, the US Seventh Fleet moved into the Taiwan Strait; this prevented the PLA from launching an attack to take the island. It also made it possible for Chiang Kai-shek to develop the island into an anti-communist fortress. If Taiwan was protected, Tibet was not. The US stood aside as Beijing invaded and the UN General Assembly refused to debate the Chinese takeover.

The People’s Republic could not move to socialism without Stalin’s say-so. Mao sent Liu Shaoqi to Moscow, in October 1952, to attend the 19th Congress to ask Stalin if China could start building socialism. The vozhd said it could but it had to proceed ‘gradually’, and he advised Mao not to rush collectivisation.

The Korean War led many Americans to fear that a war against the Soviet Union was inevitable. Even Henry Kissinger viewed the USSR, at that time, as a revolutionary power which, inevitably, would have to fight the US because it was the bulwark of capitalist democracy. When war came, thought Kissinger, the best location would be the Middle East rather than the vast plains of the Soviet Union where the Soviets had a strategic advantage. Washington had to avoid being sucked into wars on the Soviet periphery, such as Korea, where the Americans had limited or no ground forces. Hence the policy of containment of the Soviet Union around the world would not be effective and the only way of achieving real deterrence was the threat of a nuclear war with the US. The devastation of Korea would encourage small states to purchase neutrality in order to divert Soviet forces elsewhere. Western Europeans needed to expand their defence budgets to give the impression they were willing to fight. Limited American ground forces would be deployed there and diplomatic aid would be guaranteed (Ferguson 2015: 315–17).

In January 1951, a meeting took place between the Soviet leadership and top officials from the eastern bloc. The Soviet side was represented by Stalin and several members of the Politburo and military. Eastern European countries sent their party leaders and defence ministers (only the Polish Party leader was absent). General Sergei Shtemenko, chief of the General Staff of the Soviet armed forces, spoke about the growing threat from NATO and the need to counterbalance it by increasing the military capability of the socialist countries. The Soviet satellites were told to increase greatly their military might within three years and to create a military-industrial complex to make this possible. Shtemenko laid down specific targets for each country.

The Polish defence minister, Marshal Konstantin Rokossovsky, pointed out that such an expansion was planned for 1956 and therefore could not be realised by 1953. Other states also doubted their ability to attain such targets, but Stalin stood firm and insisted the goals be reached. Rokossovsky’s point about 1956 was fine, said Stalin, providing he could guarantee that war would not break out before 1956. Because he could not, the original plan was to be implemented.

Stalin was preparing for an eventuality which included a military confrontation. The Soviet military, reduced to 2.3 million by 1949, had grown to 5.8 million by 1953. Military expenditure grew by 60 per cent in 1951 and 40 per cent in 1952, but these are estimates and the actual outlay may have been higher. Investment in the civilian economy, on the other hand, only grew by 6 per cent in 1951 and 7 per cent in 1952.

Highest priority was afforded nuclear weapons, rocket technology, jet bombers and fighters and an air defence system for Moscow. During his last year, Stalin was determined to surpass the defence capacity of his adversaries. In February 1953, he launched major programmes in aviation and naval ship construction. There were to be 106 bomber divisions by the end of 1955 – instead of the thirty-two in 1953. This involved constructing 10,300 new planes over the period 1953–5 and increasing naval and air force personnel by 290,000. The naval expansion involved the building of medium and heavy cruisers by 1959. Soviet military bases were established in Kamchatka and Chukotka, near the maritime boundary with the US (Khlevniuk 2015: 297–8). Did this huge military build-up presage a Soviet pre-emptive strike against the West? Given Stalin’s state of mind in 1953, anything was possible.

In early 1951, Stalin proposed the holding of another Cominform conference and to nominate Palmiro Togliatti, the general secretary of the Italian Communist Party (PCI) as the general secretary of the Cominform. But Togliatti declined the offer and no conference was held. What was behind Stalin’s proposal? Was he contemplating encouraging Western European communist parties to attempt to seize power?

During the 1930s, the Cambridge spies (Guy Burgess [leader], Kim Philby, Donald Maclean, Anthony Blunt and John Cairncross) – dubbed the Fabulous Five – provided Stalin with voluminous material. The talent spotter, recruiter and mentor of the spy ring (he did not recruit Philby) was James Klugman who was a CPGB functionary and had spent time at Mao’s base camp at Yan’an and played a decisive role in convincing Churchill to support Tito and the communist Partisans (The Spectator, 5 December 2015). Burgess, for instance, forwarded 4,604 documents (over twice as many as Blunt) before 1939, but Stalin suspected that they were a plant, having been so detailed and informative. The Soviets received so much intelligence material they could not cope with all of it. The wartime material was invaluable to Stalin as it provided him with British and American negotiating positions at all the Big Three meetings, and American spies sent US analyses and goals as well. Burgess and Maclean defected to the Soviet Union in 1951 and Philby in 1963. Blunt confessed in 1964 and was granted immunity and John Cairncross admitted spying in 1951 but was not prosecuted.

It was not all one-way traffic. Wilfrid Mann, a brilliant British physicist involved in the Manhattan Project, spied for the Soviet Union but was turned and worked for the CIA. In 1951, he joined the National Bureau of Standards as the head of its Radioactivity Section. For the next thirty years he was the most influential radionuclide meteorologist in the world.

The Fab Five caused enormous damage to Western intelligence but Britain owes a huge cultural debt to them. They ‘changed the country beyond all recognition by wrecking the smug assumptions of the post-war ruling class, shaking the intelligence community to its foundations and ushering in a new world: less comfortable and complacent and above all, less clubby’. The establishment was deeply shocked, often unwilling to believe that men born to privilege, educated at public schools and Cambridge, could possibly be communist spies. Burgess was at Eton, Maclean at Gresham’s, Philby at Westminster and Blunt at Marlborough, all of whom were members of the most prestigious clubs. (Cairncross was the exception and studied at Glasgow University, the Sorbonne before going to Cambridge.) Class protected them from suspicion. Philby described the ‘genuine mental block that stubbornly resisted the belief that respected members of the establishment could do such things’. He understood this mentality and exploited it ruthlessly. The archives reveal the slow realisation that the service ‘had fallen victim to its own ingrained assumptions about class, background, education and social status’. The old boy network has never recovered from this catastrophe, and the scandal did much to undermine deference to wealth, accent and privilege. The Fab Five accidentally made Britain a more egalitarian country.

[The] best symbol of the transformation wrought by the Cambridge spies is James Bond himself. Ian Fleming was a clubman but 007 is not. While ‘M’ takes Bond to lunch at the fictional Blades club, Bond is not a member. An orphan at 11, Bond has no father to ease him into the right clubs.

He is classless and independent, and this stands out in Spectre, the 2015 film. He defends the establishment but is outside it, and he becomes the perfect post-war spy (The Times, 23 October 2015).

The Briton who possibly became the most famous Soviet spy was Rudolf Ivanovich Abel. He was born William Fisher in Newcastle upon Tyne in 1903. His father, Genrikh Fisher, was a metal worker in St Petersburg and a Marxist who had moved to Germany and then England. William was proficient in English, French, German and Russian. The family moved back to Soviet Russia in 1921, and William joined the Red Army as a radio operator and translator. He joined the OGPU, secret police, and was posted to Oslo and London during the 1930s and became involved in radio deception. He entered the US in 1948 as part of a spy ring in New York City. He did not have diplomatic cover and worked at various jobs while running agents. By then, he was known as Rudolf Abel. The name was that of a dead KGB colonel. Eventually, he was betrayed by an associate in Brooklyn and arrested in 1957, but he avoided the electric chair and was imprisoned and then exchanged in February 1962 – as KGB Colonel Vilyam Fisher – for Gary Powers at the Glienicke Bridge, which connected West Berlin to Potsdam, in the German Democratic Republic (GDR). Abel died in 1971 and was honoured on a Soviet postage stamp. He is the subject of the 2015 Steven Spielberg film, Bridge of Spies, and Abel is brilliantly played by Mark Rylance.

The most successful Soviet spy in Israel was Avraham Marek (Marcus) Klingberg, an internationally acclaimed expert on chemical and biological weapons who, as deputy director of Israel’s secret Ness Ziona biological weapons research centre, had access to all Israel’s top secrets in this clandestine field. It is reasonable to assume he handed all these secrets on to ‘Viktor’, his Soviet handler (they met in the Russian Orthodox Church in Tel Aviv); Moscow, in turn, passed the information on to Arab countries. Israel admits that Klingberg did more harm than any other spy in the country’s history. After the Soviet Union and Israel severed diplomatic relations in 1967, they met in Switzerland and at international conferences. Born in Warsaw in 1918, into a Hassidic Jewish family, Klingberg studied medicine at Warsaw University, and when Germany invaded, he moved to the Soviet Union and completed his medical studies in Minsk. He served in the Red Army at the front but was sent to Perm to study epidemiology and became chief epidemiologist in Belarus. The war over, he returned to Warsaw and began working for the Polish government. He married another communist, and in 1946 they moved to Sweden (they could not obtain a US visa), where he established contact with Soviet intelligence; in 1948 they emigrated to Israel. A brilliant research scientist, he became an officer in the Israeli army and then joined the Israel Institute for Biological Research which, it is believed, manufactured poisons used by Mossad, the Israeli secret service. He went on research visits to the US, Norway, London and Oxford, where any information he was able to glean about biological and chemical warfare weapons was passed on to Moscow. He was unmasked by a double agent in 1983, kidnapped by Israel security, tried and given the maximum sentence of twenty years, but he then simply disappeared. In fact, he was imprisoned under a false name and kept in solitary confinement for ten years. In 1993, after the collapse of the Soviet Union, Israel admitted that he was being held prisoner and in 2003 he was released. In his memoirs, Der Letze Spion (The Last Spy), published with Michael Sfard and Wiebke Ehrenstein in 2014, he argued that he was always motivated by Marxism and that, scientifically, the sensitive material he had access to should be shared internationally. His grandson commented: ‘He remained a communist to the end and faithful to communists and Russia’ (The Times, 8 December 2015).

The Office of Strategic Services (OSS) was set up on 13 June 1942 and headed by ‘Wild Bill’ Donovan to provide mainly intelligence about Germany, and it was wound up on 20 September 1945. The CIA appeared on 18 September 1947. As there was an urgent need for information about the Soviet Union, a Research and Analysis Division was set up staffed by many prominent academics, including leading Marxists such as Paul Sweezy, Franz Neumann and Herbert Marcuse – the OSS’s leading analyst on Germany. The latter concluded that the only credible opposition to Nazism in Germany were the communists. Finding out what was happening in the Soviet Union was a problem, as copies of Pravda and Izvestiya arrived in Washington six weeks late. Due to lack of Soviet data, they used German material to estimate what was happening on the Eastern Front. They correctly predicted that the Wehrmacht could not win at Stalingrad because of the insuperable logistical problems, but they did foresee the looming problem of dealing with the Soviet Union after the war. It was pointed out that the USSR would be a growing power, the US a satisfied power and Britain a declining power. Concessions to Moscow should be made in order to secure peaceful coexistence. One of the best British sources turned out to be the Japanese ambassador in Berlin whose reports to Tokyo were decoded by Bletchley Park (where Enigma was deciphered). The ambassador reported that Stalingrad was the greatest German defeat since Napoleon had smashed the Prussians at Jena in 1806. The Soviets provided London and Washington with very sparse information about what was happening on the Eastern Front.

Towards the end of the war, thoughts turned to acquiring the Wehrmacht’s intelligence network on the Eastern Front. Lt Colonel Reinhard Gehlen, senior intelligence officer of the Wehrmacht on the Eastern Front, became a German star. He proved no more accurate at predicting where Red Army attacks would occur than the General Staff and was sometimes completely wrong. The reason his reputation grew was his skill in recruiting agents behind the Soviet front line who provided valuable information which influenced how the Wehrmacht was deployed. The conclusion is that he was one of the most influential intelligence officers on either side during the war. On the other hand, the latest information suggests he was brilliantly misled by Soviet intelligence. One of his key agents was Aleksandr Demyanov, codenamed Max who, in reality, was an NKVD officer feeding him information, some of which Stalin himself authorised. One of the ways the Soviets built up his credibility was to report his group had conducted railway sabotage near Gorky (now Nizhny Novgorod), and newspapers duly report this canard. Max provided a constant flow of reports about the Red Army’s order of battle and strategic intentions, and Berlin was overjoyed to receive such valuable material. Stalin was taking a huge risk in providing some accurate information about the battle plans of the Red Army, presumably to secure even greater military advantage elsewhere.

Gehlen, once he had perceived that Germany would be defeated, concluded that the next conflict would be between the Soviet Union and the West. He therefore gathered all the material of his intelligence apparatus and ensured it was not destroyed. After defeat, he offered the Americans his services including all his personnel and files; Washington welcomed him with open arms. The Gehlen Bureau later became an important part of the CIA’s operations in Europe. This delighted the NKVD (it became the MSS in 1946 and the KGB in 1954) and the GRU (military intelligence) to no end. After all, they controlled almost all his sources and were aware of most of the others (Hastings 2015: 223–38, 544–5).

In 1944, the young American physicist Ted Hall, working on the Manhattan Project, told his NKVD handler that ‘There is no country except the Soviet Union that can be entrusted with such a terrible thing’ (Hastings 2015: 524). Around fifty of the scientists in Britain and the US provided atomic secrets to Moscow, and it was the greatest espionage coup of the war for the NKVD and GRU. It did not affect the war against Germany and Japan but it had a formative influence on the atomic age.

In 1940, Soviet scientists concluded that an atomic bomb from enriched uranium was feasible, and on 16 September 1940 Donald Maclean – one of the Fabulous Five of British spies – forwarded a report to Moscow on a project codenamed Tube Alloys. In August 1941, Klaus Fuchs, a German-born physicist and committed communist, was recruited by a GRU agent. In March 1942, Beria sent Stalin a report on British atomic research, mainly supplied by John Cairncross.

Robert Oppenheimer, now leading the Manhattan Project, met the NKVD rezident in San Francisco and told him of Einstein’s 1939 letter to Roosevelt about the Germans working on an atomic bomb. He may also inadvertently have provided hints about the US project. In January 1943, Bruno Pontecorvo, an Italian-born British subject, reported to the NKVD about the first nuclear chain reaction, and by July 1943 Moscow had received 286 classified US documents on the Manhattan Project. In Britain, Melita Norwood, recruited in 1937, was providing vital information (she was only unmasked in 1999 but not prosecuted) and proved to be Moscow’s most important atomic spy in Britain, but Soviet spies could get it wrong. On 1 July 1943, the NKVD station in New York reported that 500 individuals were working on the Manhattan Project, but the correct figure was 200,000, which was to rise to 600,000 if all subcon-tractors are added. In late 1943, Klaus Fuchs was transferred to the US and began to provide regular weekly reports on progress. The Washington rezident’s office received 211 rolls of classified documents in 1943, 600 in 1944 and 1,896 in 1945. These included valuable material on radar, wireless technology, jet propulsion and synthetic rubber which permitted Soviet industry to advance. Beria became suspicious about the flow of classified material because it was so easy to obtain. Twelve days before the US bomb was assembled at Los Alamos, Fuchs and Pontecorvo provided descriptions of the bomb to their handlers. When the first Soviet atom bomb was detonated, in August 1949, it was very similar to the ‘Fat Man’ plutonium bomb dropped on Nagasaki.

American security gradually improved and Julius Rosenberg was sacked from Los Alamos because of his Communist Party membership. After the war, a Soviet specialist estimated that the FBI had only uncovered half of the Soviet network (Hastings 2015: 524–35).

In January 1950, the confession of Klaus Fuchs that he was a communist spy led to an intensive investigation by the US and British authorities. He had handed over 246 pages of secrets between August 1941 and October 1942 and a further 324 pages by November 1943. Another British spy, Alan Nunn May, acquired 142 pages on the Manhattan Project and passed them on to his Soviet contact. Another key scientist, never identified, supplied about 5,000 pages of secret documents (Haslam 2011: 62). Bruno Pontecorvo defected to the Soviet Union in September 1950, and he had worked on the British atomic bomb at Harwell under Sir John Cockcroft.

Fuchs identified Harry Gold as his courier and he was arrested in the US in May 1950; the latter revealed that David Greenglass was another source. His sister, Ethel Rosenberg, and her husband, Julius Rosenberg, were arrested and accused of passing atomic secrets to the Soviet Union. Greenglass’s wife Ruth was in fact a spy, but Greenglass, in order to save his wife, identified Ethel Rosenberg as a spy. Allegedly, she had typed some documents for her husband, but she was innocent because Greenglass’s wife had typed the documents. Julius and Ethel Rosenberg were executed in April 1953; they were the only US civilians to suffer such a fate for passing Manhattan Project secrets to Moscow. Greenglass served time in prison and the charges against his wife were dropped, but he never expressed remorse for his false testimony which led to his sister being sent to the electric chair. He said he expected to be remembered as the spy who ‘turned his family in’. Others were more successful in covering their tracks; Alger Hiss, for example, fooled his interrogators.

In February 1950 the revelations about spying were seized upon by the junior senator from Wisconsin, Joseph McCarthy, who declared dramatically that he had evidence that the State Department was replete with communists. He claimed to have a list of no fewer than 206 members of the Communist Party of the USA in the Department. Allegedly, there were communists in the military and elsewhere. He argued that Truman was soft on communism and had ‘lost’ China, but the claims were dismissed by the Truman administration. The witch hunt for communists, labelled McCarthyism, reached hysterical heights, and it revealed the deep insecurity of the US facing a Soviet Union with nuclear weapons. It is worth noting that the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC), in hearings involving Hollywood (up to 1958) heard evidence from seventy-two ‘friendly witnesses’ who identified 325 film people as present or past communists.

One of the puzzles about espionage is why so many British and American specialists spied for the Soviet Union; they appeared to regard the Soviet Union as an earthly paradise in the making but ignored all the information about how brutal the Stalin regime was. Many of them were well off and, in the case of several of the British spies, from a privileged background.

National Security Council Report No. 68 (NSC-68) established a framework for US defence which lasted for most of the Cold War. Paul Nitze chaired the committee, which drafted the report after President Truman had requested it in January 1950; the president approved it in 1951. The dramatic language adopted was typical of the era. The ‘issues that face us are momentous involving the fulfillment or destruction not only of the Republic but civilization itself.’ It called for a rapid increase in defence spending to contain the expansionary policies of the Soviet Union. Hence it can be called a military response to Kennan’s diplomatic vision of containment, but rollback or offensive military action was excluded. Kennan opposed the massive increase in military spending. The goal was to build a coalition of nations to prevent the advance of communism; if this was not achieved then the Soviet Union could develop to the point where no coalition of the willing could successfully oppose it. Hence it expected the USSR to rapidly expand militarily and economically. There were those who regarded this as much too optimistic but the Korean War won over many. Secretary of State Dean Acheson acknowledged that the war provided the critical impetus; Truman opposed a rapid expansion of the military budget but gave in. In 1950 defence accounted for 5 per cent of GDP and climbed to 14.2 per cent in 1953. The military-industrial complex was gathering momentum. This term is associated with President Eisenhower, who used the expression in his Farewell Address on 17 January 1961. He had originally intended to say military-industrial-congressional complex as a result of some congressmen, including his successor as president, who kept harping on about a missile gap which had to be closed at all costs (Ferguson 2015: 463n).

There was an alternative to the use of military force: psychological warfare (PW). The concept surfaced in 1950 and was promoted by William Yandell Elliott III, who participated in the setting up of Radio Liberty, which targeted the Soviet Union. He also favoured cultural exchanges to bring young people to the US to imbibe the American experience, and they were to be trained to run their own countries. Hearts and minds also had to be won at home as it was unwise just to rely on US values, such as the free market, to carry the day. The first time PW was deployed was during the Italian elections of April 1948 to prevent communists and socialists winning a majority. Financial aid permitted the Christian Democrats to engage in black propaganda such as warning Italians that if the communists took over, all males would be deported to the Soviet gulag! Frank Sinatra and other Hollywood stars wrote to their relatives warning them of the dire consequences of a communist victory. The Christian Democrats won 305 seats, a clear majority. An Office of Special Projects (later the Office of Policy Coordination [OPC]) was set up. The OPC specialised in founding front organisations: the National Committee for a Free Europe, which ran Radio Liberty; the Free Trade Union Committee; Americans for Intellectual Freedom; and the Congress for Cultural Freedom, to name only a few. PW was hugely popular and every agency wanted to get involved, but this resulted in confusion. A Psychological Strategy Board (PSB) was set up in 1951 to speak with one voice, but this was never achieved as some wanted to wipe communism from the face of the earth and others merely to engage in coexistence; the net result of all its activities was rather disappointing (Ferguson 2015: 263–4). President Eisenhower was a cautious conservative but he had a heart of steel. He defined PW as the struggle for the minds and wills of men and American values had to beat Soviet values. George Kennan had pointed out that a revolutionary state such as the Soviet Union was permanently insecure and that the battle of ideas would continue until one side won and took over the world.

During the Korean War, in 1951, the PSB sent Henry Kissinger to South Korea to write a report on civil-military relations. He concluded that military officers had to be alert to the fact that civil affairs were of critical importance in achieving political and military objectives. He next went to Germany, where he found a pervasive distrust of the US and propaganda did not work because it was too reminiscent of Goebbels. In the western zones, Americans were perceived as more brutal and arrogant than Russians and were inconsiderate, insensitive and cynical. The Soviets were much more successful because they stressed peace and the unification of Germany. The Americans would not win until they emphasised the ‘psychological component’ of their political strategy. The solution was to found a ‘university, large foundation, newspaper and similar organization’. Germans and Americans needed to work together in joint projects and establish a community of interests in study groups, cultural congresses, exchange professorships and intern programmes, under non-governmental auspices (Ferguson 2015: 270–1). PW would then carry the day. Nowadays, this is called ‘soft power’.

Some wondered that if Moscow was willing to use force in an attempt to reunite Korea, could the same policy be adopted in Germany? More NATO troops were needed in Europe. Konrad Adenauer, the West German chancellor, began talks about founding a new German army in 1950, but it was not until November 1955 that the Bundeswehr appeared; this was because of opposition by other European powers, especially the French. General Dwight D. Eisenhower was named Supreme Allied Commander in Europe, and more US divisions were expected to be moved there.

Japan’s fortunes changed as well, as it had supplied the lion’s share of the provisions needed by the UN forces in Korea. In September 1951, a peace treaty was signed in San Francisco which envisaged American withdrawal by May 1952. All belligerent states signed except the Soviet Union, China, North Korea and other communist states. The US retained some military bases and Japanese security was guaranteed by Washington. The Philippines, Japan, Australia and New Zealand signed security pacts with the US, and in Europe, Greece and Turkey joined NATO. The Americans then turned their attention to the Middle East. Stalin could decipher the Soviet Union being surrounded by a ring of states who owed their security to Washington (Cohen 1993: 58–80; LaFeber 1993: 99–145).

Stalin regarded Germany as the key country in Europe, but he did not envisage it being divided into two states – one communist and the other capitalist – so his German policy was always pan-German. His major objective was to ensure Germany never again threatened Soviet security and this could be achieved in various ways. The favoured option was that Germany become a neutral, demilitarised state. The four occupying powers would still retain responsibility for ensuring that Germany never became a military threat but the Berlin Blockade transformed the situation. It led to the formation of the Federal Republic of Germany (FRG) in the west and the German Democratic Republic (GDR) in the east. The FRG was gradually integrated into Western Europe, and this ensured it would develop as a capitalist state and be under American influence.

Stalin’s response was the note of 10 March 1952, which proposed a German peace treaty and a united, neutral, demilitarised Germany. Freedom of speech and assembly were guaranteed, and all occupation forces would leave within a year of the signing of a peace treaty. The note was made public by the Soviets, a move which compromised diplomatic negotiations. This has led many historians to view the note as an attempt to sway the West German public and halt the integration of West Germany in Western Europe. West Germany was to be included in the European Defence Community (EDC), but it never came into existence because the French National Assembly voted against it. A further note followed on 9 April and other notes came on 24 May and 23 August. The Western response was dominated by Konrad Adenauer, the West German chancellor, who regarded it as insincere and as a delaying tactic to prevent the integration of West Germany in the EDC and other European institutions. He was also aware that a united Germany almost certainly would elect a social democratic government, and his Christian Democratic Union–Christian Social Union party would thus lose its majority in a pan-German parliament.

The failure of the Western powers to respond positively to the notes gave rise to a heated controversy about a ‘missed opportunity’ to reunify Germany. The valid point was made that Stalin’s sincerity should have been put to the test. It is striking that Winston Churchill, again British prime minister, did not argue in favour of negotiations to test Soviet intentions; the US administration was also lukewarm and deferred to Adenauer.

Soviet archives reveal that the origin of the 10 March 1952 note goes back to 1951. It was regarded as a delaying tactic, and Stalin only consented to it being sent after being assured that it would be rejected. There is no indication that Moscow was willing to sacrifice the GDR to obtain a united, neutral Germany which would have been capitalist.

Stalin loved watching films until the early hours, and members of the Politburo were required to attend. Stalin sat alone in his row behind everyone else. One visitor, the director of the film, was searched fifteen times before he was allowed to sit down. Then Stalin’s secretary brought him a message. ‘What’s this rubbish?,’ he commented, but the director thought he was commenting on his film, fainted and was carried out. And ‘they didn’t give him a new pair of pants for the ones he had soiled, either,’ commented the Boss. Among Stalin’s favourites were The Great Waltz about Johann Strauss, which he saw dozens of times. He loved the Tarzan films and saw every one – so did everyone else. The Red Army had seized many American films in Berlin, including those starring Johnny Weissmuller, and they were gradually released to the public. Boys would wear Tarzan haircuts and utter war cries which were said to be so piercing that they disturbed cattle on the collective farms and kept cows from giving milk! Some Russians believed Tarzan was a real person. So pervasive was the Tarzan cult that the party stepped in and started a campaign against it. Mikhail Chiaureli’s The Fall of Berlin (Padenie Berlina) was a seventieth birthday gift for Stalin in 1949. The hero and heroine are summoned to meet Stalin in his white tunic in a beautiful garden, where Stalin is carrying a hoe and listening to the birds singing. The Germans then attack, and Stalin and his generals confer during the defence of Moscow. Hitler, the corpulent Göring and the limping Goebbels (he had a club foot) are chatting with diplomats from Japan and the Vatican. The Führer rants and raves in Russian, and Göring is chatting to an American who toasts the imminent fall of Stalingrad. Shostakovich’s music accompanies the Soviet victory. At Yalta, the cunning, double-chinned Churchill puffs on a cigar, and Roosevelt nods as Stalin unfolds some maps. The battle of Berlin is dramatic, with everyone looking up as Stalin’s plane lands in Berlin; this is followed by quasi-religious scenes of adoration. The only problem is that Stalin did not go to Berlin. The film was widely distributed in Western Europe, but it was only in 1952 that it hit America. The New York Times dismissed it as a ‘deafening blend of historical pageantry and wishful thinking’. Stalin alighting in Berlin was like a ‘Gilbert and Sullivan frolic’. However, there were American critics who regarded it as a ‘masterpiece of cinema art’ (Caute 2003: 143–7). I saw the film in the 1950s and it made a great impression on me, especially the scene where Stalin descends from his plane like God from Heaven. After Stalin’s death it was lambasted by the critics. Shostakovich took his revenge on Chiaureli and claimed he could not tell a piano from a toilet bowl.

The Conspiracy of the Doomed (1950) was widely distributed. A US ambassador, MacHill – villains in Soviet Cold War–era films were usually call Mac something – arrives to arrange a crop failure to overthrow the communist government (apparently Czech). The suave diplomat is also plotting the assassination of the deputy prime minister. A devious cardinal – probably modelled on Cardinal Minszenty, Primate of Hungary – tells everyone the drought is God’s punishment for forsaking Him. It turns out that there is no grain shortage – it was being hidden by kulaks all along and workers take over and chant: ‘Stalin, Stalin’. The ambassador curses everyone and flies away. The film never reached the US but this did not stop some American critics rubbishing it based on Soviet reviews. Nevertheless, it is regarded as one of the two best Cold War films produced in the Soviet Union.

They Have a Native Land (1949) tells the story of Soviet children captured in Germany by the British and Americans and some are put on a ship for New York. They ‘want to send them to be cannon fodder in a new war’, the voiceover explains. Frau Wurst (‘Mrs Sausage’) asks a British officer for a slave girl with blue eyes and the officer obliges, but all ends happily as the children are returned to the Motherland. The British and Americans all speak impeccable Russian – they were in counter-intelligence, of course.

What message came through Soviet Cold War–era films? The Soviet Union defeated Germany and Japan without any help from the US and Britain; it did so despite an Anglo-American conspiracy to help Germany and Japan; victory was due entirely to the leadership of Stalin. The Anglo-American conspiracy appeared time and again, but Roosevelt was always held to be innocent . The Secret Mission (1950) drew protests from London and Washington. Americans are shown running away from a German offensive in January 1945. Montgomery shouts into the telephone: ‘I won’t help the Americans. They can go to the devil.’ Churchill appeals to Stalin for help and complains the Americans are ready to negotiate a separate peace with Germany. Heywood, a US senator, says: ‘We held up the second front for two years to cheat the Russians.’ Himmler replies: ‘We have left the Western front deserted.’ German troops are shown surrendering to the Americans in ceremonial order. How this fits with the beginning of the film, which showed Americans fleeing in panic, is not explained. Vice President Truman is presented as the person who sent Heywood to inform Hitler about the forthcoming Soviet offensive, and the German industrialist Krupp promises Heywood that he will preserve his military factories in West Germany but destroy those in East Germany before the Soviets arrive. Krupp thanks Heywood for all the raw materials he received to continue his war production. Heywood goes to the Balkans to meet Hitler supporters and he is told that if things get too hot to go to Yugoslavia where he will be safe. This was the film’s swipe at Tito. In the last scene, Churchill promises a new world war and expects it to cost the lives of half of the world’s population before it ends. No wonder the British and American governments were outraged at the total falsification of history. The film was a runaway success in the Soviet Union.

Silvery Dust (1953) deals with the African American question and is set in the American South. White racists are willing to sacrifice blacks in pursuit of a ‘death ray’. Blacks are sentenced to the electric chair but the Ku Klux Klan moves in to execute them themselves. A general intervenes, and the blacks are put in a laboratory cage and expected to die from ‘silvery dust’, but peace partisans raid the laboratory, rescue the African Americans and warn the white racists that they will face a people’s court one day. The American delegate even complained in the UN Security Council about the ‘extravagant fictions in which all the villains are Americans. For many years the Soviet Union has been busy at just this sort of thing.’ The Soviet representative commented that he had encountered dozens of American films which contained outrageous slanders against the Soviet Union. Cold War films, he admitted, presented superficial ‘psychological portraits’ but overall reflected the reality of the ‘imperialist conspiracy’.

The Woman on Pier 13 was one of the first ‘Red Menace’ (1949) films to be favourably reviewed. It concerned communist manipulation of labour on the San Francisco waterfront; the party ruthlessly disciplines its members. I Was a Communist for the FBI (1951) has a leading communist committing a fictitious murder. To ‘bring communism to America we must incite riots’ is a comment. Communists are portrayed as the sworn enemies of African Americans, workers and Jews. In My Son John (1952) a wholesome American mother has two sons fighting in Korea ‘on God’s side’, but the third one, John, is a red and she hands him over to the FBI. Informing on family members as a civic duty appears in many American Cold War movies. John decides to confess but his party comrades murder him before he can; however, he had taped his confession beforehand in which he confessed he was a traitor and a communist spy. Walk East on Beacon (1952) praises the FBI for protecting Americans from communism. They uncover a vast network of spies trying to steal the secrets of a path-breaking new computer. Big Jim McLain (1952) starred John Wayne as an agent who deals with communists on the Honolulu waterfront. Big Jim’s assistant is murdered, and the communist plan is to paralyse communications and halt the flow of war matériel to Korea. Big Jim has a punch-up with the bad guys before they are arrested.

An arts festival held in West Berlin in 1951–2 revealed how seriously the State Department took cultural competition with the Soviet Union. Porgy and Bess was a hit with Berlin audiences, and the Boston Symphony Orchestra and others gave concerts; the Americans enthused that US prestige had risen more in one month than in the previous seven years.

A Soviet cultural festival took place in Paris in April 1952. Works by Prokofiev, Ravel, Copland, Rachmaninov and Richard Strauss were played; Stravinsky, who had fled to Paris in 1939, returned to conduct his own work. Works by composers banned under Hitler were performed. In December 1952, six Soviet musicians ventured as far as Edinburgh to give a concert in a half empty Usher Hall, and listeners were very impressed by their technical skill.

Jazz was all the rage in the Soviet Union after 1945. The Red Army even had a jazz band and the Communist Party set up its own. Then during the Zhdanovshchina jazz was banned not only in the Soviet Union but also in Eastern Europe. It was derided as ‘black music’ and, in 1949, all saxophones were confiscated, and many jazz musicians ended up in the gulag. Many American jazz bands toured Europe and Japan. Louis Armstrong took France by storm and the Pope thanked him. The Voice of America and the US army in Germany and Austria broadcast jazz to an adoring audience. Jazz in Moscow was seen as a narcotic, a way to dope workers and hypnotise the will by machine rhythm. Paul Robeson maintained that the ‘real’ Negro music was spirituals and the blues.