1953–62

Stalin was reported dead on 5 March 1953. The people mourned, and some were even crushed to death trying the see the vozhd. Others celebrated, first and foremost Lavrenty Beria, but the last years of Stalin were replete with fear. At the 19th Party Congress, the Politburo was replaced by the Presidium with twice as many members as before. Was Stalin preparing a purge of the old guard to make way for a new, younger Stalin cohort? Dmitry Shepilov, a member of the Central Committee of the party and later editor of Pravda, attended the Congress which he found awe-inspiring but Stalin’s behaviour troubled him. He was condescending towards his closest colleagues and hurled accusations at them. Marshal Kliment Voroshilov was guilty of ‘espionage’; Vyacheslav Molotov and Anastas Mikoyan had ‘capitulated to American imperialism’.

Could all this be a product of Stalin’s schizophrenic paranoia? … To question Stalin or try to object – these outlandish ideas did not occur to anyone. The pronouncements and views of the genius Stalin could only be reverently and rapturously acclaimed.

(Shepilov 2007: 235)

In January 1953, Pravda had announced the discovery of a Doctors’ Plot. Since 1945 several leading politicians had allegedly been murdered by a group of doctors, most of whom were linked to a Jewish organisation run by the Americans. One of those accused confessed that he had been ordered to ‘eliminate the leading cadres of the Soviet Union’, and this included Comrade Stalin. The newspaper assured readers that documentary evidence to prove these heinous crimes was available. Ministries were accused of slackness and the Komsomol of lacking vigilance, and Stalin devoted a lot of time to the fabrication of evidence against the ‘wrecker doctors’. Their patrons were to be found in the Ministry of State Security.

The minister, Semyon Ignatiev, suffered the full force of Stalin’s foul-mouthed insinuations which included calling officers ‘hippopotamuses’ and he was going to ‘drive them like sheep and hit them in the mug’. Several leading doctors who treated the Kremlin elite were arrested in October and November 1952, and Stalin told investigators to use torture. The Minister informed Stalin that two of his most skilled torturers had been assigned to the case but there was resistance to the brutal methods being deployed. A Party Presidium meeting, on 4 December 1952, passed a resolution on the work of the Ministry of State Security.

Many Chekists [Ministry of State Security officials] hide behind … rotten and harmful reasoning that the use of diversion and terror against class enemies is supposedly incompatible with Marxism-Leninism. These good for nothing Chekists have descended from positions of revolutionary Marxism-Leninism to positions of bourgeois liberalism and pacifism.

In a closed session, Stalin made clear what he wanted done. ‘Communists who take a dim view of intelligence and the work of the Cheka, who are afraid of getting their hands dirty, should be thrown down a well head first’ (Khlevniuk 2015: 308). Rumours swirled around Moscow about possible pogroms and the expulsion of Jews from Moscow and other cities. No evidence has come to light that Stalin was planning anything comparable. Then suddenly, on 23 February 1953, the whole campaign was dropped. Shortly after Stalin’s death, the so-called plot was acknowledged as a fabrication, and the deputy Minister of State Security was indicted and executed.

After Stalin’s death a collective leadership of Malenkov, Molotov and Beria would ‘prevent any kind of disorder or panic’, but the collective leadership could only last until a new, strong leader took over. Tension was relaxed at home and abroad. Georgy Malenkov had already talked about peaceful coexistence in 1952 and now promised the Soviet population higher living standards; and he held out an olive branch to Tito and assured the capitalist world of the Soviet Union’s peaceful intentions. Beria launched a few initiatives of his own, proposing the promotion of non-Russians (he himself was a Georgian) in non-Russian republics. He also released many from the gulag, and they flooded back to Moscow demanding justice and compensation for their ordeal, and he even toyed with the idea of a unified, neutral Germany which meant sacrificing the German Democratic Republic (GDR). The uprising in East Berlin and elsewhere in the GDR, on 17 June 1953, took him to Berlin. While he was there Khrushchev organised a cabal against him; the day after he returned, he was arrested and executed along with some of his subordinates later in the year. The intriguing question remains: had Beria become dominant in Moscow, would Germany have been united and the situation in Eastern Europe transformed? The uprising in East Berlin ensured that the GDR could not be sacrificed. As Khrushchev later argued, it could have led to the unravelling of the Soviet position in Eastern Europe.

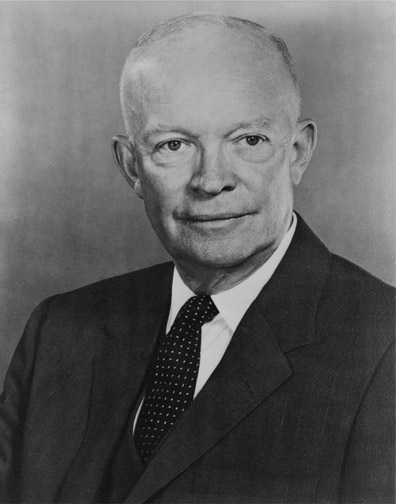

When Stalin died there was a new president in the White House, Dwight D. Eisenhower, a war hero and former commander of allied troops in Europe. He was a rara avis (a rare bird), a world politician who was a modest man. There was also a new secretary of state, John Foster Dulles – he was not a modest man. He had served under Truman and regarded himself as an expert on foreign affairs. Eisenhower’s vice president was Richard Nixon, who had made his name as a communist-bashing lawyer.

If the Cold War could be attributed to Stalin, it could now be expected to end. The vozhd did not think his minions were up to the task of running the great country he had created. Stalin and Molotov decided foreign policy so his successors would be faced with challenges which would be novel to them. Khrushchev, with Stalin safely dead, commented that the Boss had laid too much store on military might and, needless to say, his former colleagues blamed the vozhd for all the failures of the post-war era – the Korean War, the Berlin Blockade and the estrangement of Iran and Turkey. However, the new leaders shared one of Stalin’s maxims: the bloodletting of the war had accorded the Soviet Union a preeminent position in Europe and this permitted Moscow to determine the fate of Europe.

Churchill sensed that with a new collective leadership in Moscow there was an opportunity to negotiate a better relationship, so he proposed a four-power meeting to Eisenhower. The new US president was hesitant but Secretary of State Dulles was unequivocal. No good would come out of negotiating with communists. Again the 17 June uprising in East Berlin, where the Soviets had used tanks to put down the rebellion, muddied the waters. The day after its suppression, at a National Security Council meeting, Eisenhower commented that the events ‘provide the strongest possible argument to give to Mr Churchill against a four power meeting’. An allied foreign ministers’ meeting did take place in Berlin in January and February of 1954 but there was no agreement on the German question. A further meeting in Bermuda did not take place but the foreign ministers convened again, in Geneva, from April to June 1954. Whereas the previous meeting had dealt with Europe, this meeting focused on Korea and Indochina. This was the occasion when Dulles ostentatiously refused to shake Zhou Enlai’s hand.

One of the reasons for the lack of interest in détente by the Eisenhower administration was that it could have jeopardised German rearmament because reunification was to be based on the country becoming neutral. The prevailing view in Washington was that the Soviets were waxing strong while America was falling behind but, in retrospect, this was nonsense and analyses which argued that the Soviet threat was diminishing were ignored. All in all, a great opportunity was missed to engage with the new, inexperienced Soviet leadership which also wanted to reduce tension with the capitalist world. Another problem was that there was an interest group that could benefit from exaggerating Soviet military potential: the military-industrial complex.

Georgy Malenkov appeared the natural successor to Stalin. He was head of the party and the government but offered to relinquish one of these posts on 14 March and chose to remain as prime minister, a position which permitted him to chair Party Presidium meetings. Beria was feared by all and he was close to Malenkov but the latter was not a natural leader – just like Molotov – and the others were afraid he could be manipulated. The comrade with leadership qualities turned out to be Khrushchev. The latter learnt about foreign policy from Mikoyan and he learnt fast. Molotov, again foreign minister, remained fixed in Stalinist mode and was incapable of launching the new initiatives the country needed.

With Beria out of the way, Khrushchev was elected First Secretary of the party in September 1953. In September 1954, Malenkov lost the right to chair Party Presidium meetings, and in November all documents from the Council of Ministers appeared under the signature of Nikolai Bulganin, his deputy. Malenkov had to resign in February 1955 and confess that he had underestimated the need to promote heavy industry over light industry; he was also accused of stating that nuclear war would mean the end of civilisation. The view was that the leadership could hold such a view but it should not be revealed to the general public. The removal of Malenkov meant that the opportunity for détente had passed as Khrushchev followed Stalin in believing that more military might meant more security.

Khrushchev had little formal education but possessed considerable peasant cunning (this is meant as a compliment). His lack of formal education led Viktor Sukhodrev, his English language interpreter, to castigate him as ‘uneducated, uncouth, a peasant if you will’. In his memoirs, he recounts translating Khrushchev’s claim that Soviet citizens had no interest in owning a house or a car and mumbling to himself: ‘I want a car! I want a house!’ Sukhodrev also interpreted for Gorbachev at summits with Reagan and Bush. Gorbachev’s language was a challenge as it ‘was frequently very convoluted and it was hard to really find out what he was trying to say because he used too many words to spell out something simple that he had in mind’ (this is a clever parody of Gorbachev speak) (The Times, 29 May 2014).

The Soviet leader regarded China as very important and agreed repeatedly to Chinese requests to increase aid but ignored the views of technical experts that such a vast aid programme was beyond the country’s capabilities because, to him, it was a political question first and foremost. His first foreign visit was to Beijing in September and October 1954 to mark the fifth anniversary of the founding of the People’s Republic. It was deeply symbolic to Mao as it was the first time a Soviet leader had visited the Middle Kingdom. Khrushchev hugged and kissed the Great Helmsman – which greatly offended him – and provided huge gifts which included, among other things, fifteen new industrial projects; a loan of 520 million roubles for military enterprises; the transfer of all Soviet stock in joint Sino-Soviet companies in Xinjiang and Dalian; the construction of a railway from Urumqi to Alma Ata; and withdrawal of Soviet troops from the Port Arthur naval base (and Dalian) ahead of schedule and returning the base to the Chinese free of charge. On the other hand, Khrushchev did not make any concessions on Mongolia. Mao grasped the opportunity to ask for more Soviet specialists to be sent. Overall, he concluded that Khrushchev was a weak leader and needed Chinese support.

The number of Soviet technical experts rose 46 per cent in 1955, 80 per cent in 1956 and 62 per cent in 1957, and Moscow also provided 31,440 technical documents and a huge number of other technical aids. During the Chinese First Five-Year Plan (1953–7), Beijing received about 50 per cent of the aid to socialist countries, and this permitted an annual growth rate of 11.3 per cent. Aid to the Middle Kingdom was about 7 per cent of Soviet national income – a heavy burden for a state struggling to improve living standards.

Whereas the First Five-Year Plan had been drafted by Soviet specialists, the Second Five-Year Plan (1958–62) was drawn up by the Chinese. It involved a request for 188 new industrial projects and help to establish a nuclear industry. Mikoyan visited China in April 1956 and agreed to fifty-five Soviet projects and the construction of a railway from Lanzhou to Antigay in Kazakhstan. In May, Chinese planners arrived in Moscow to discuss the 188 projects and asked for assistance in undertaking another 236 projects but were told that their plans were too ambitious. Eventually, the Soviets agreed to assist the Chinese in designing 217 new projects. Soviet specialists were provided in non-technical areas, including government, law and security, and they also helped draft the new Chinese constitution.

Estimates of Soviet loans during the 1950s are as high as $2.7 billion with 95 per cent of loans during the Korean War going to the military. In March 1961, Khrushchev offered a loan of a million tonnes of grain and half a million tonnes of Cuban sugar to alleviate the famine at that time, and Beijing accepted the Cuban sugar. In 1964, China paid off all existing Soviet loans and hence declared it had no foreign debts (Shen and Xia 2015: 103–10).

The Korean War had drained US resources, and Eisenhower wanted to link increases in military expenditure to the growth of the economy. The Soviet threat was economic as well as military, and this had to be borne in mind.

The atomic stockpile grew from 169 weapons in 1949 to 823 in 1952. By 1956, hydrogen (or thermonuclear) weapons were part of the nuclear arsenal; one could wipe out an entire city. Eisenhower’s New Look policy, adopted on 29 October 1953, was based on four criteria:

- Defence expenditure was not to undermine the dynamism of the US economy; and therefore increases in one part of the armed services had to be accompanied by cuts elsewhere.

- Nuclear weapons were the main deterrent.

- The CIA was to engage in covert actions against pro-Soviet regimes.

- Defences of allies were to be strengthened and friends won abroad.

As a consequence, the Strategic Air Command was given greater prominence and land and naval forces cut. Local wars, using nuclear weapons, could be fought but a nuclear war against the Soviet Union was now unthinkable. The president was to be the sole judge of when nuclear weapons could be used, but gradually he moved away from regarding them as a weapon of first resort. Threatening a nuclear attack became a salient part of diplomacy known as brinkmanship. There was even discussion of a preventive war after the Soviet Union became a nuclear power in 1949 but this was ruled out in late 1954. Europeans, especially, opposed nuclear war because the continent would inevitably be devastated.

The first time that brinkmanship and the threat of a nuclear strike were tried was in March–May 1954 when the French, at Dien Bien Phu in north western Vietnam, appealed for air strikes to break the Viet Minh siege. The French wanted to strengthen their position at the Geneva talks, which began in April, and then leave Vietnam with some honour, but the Americans wanted to defeat the Viet Minh because they saw them as a proxy for the Chinese. Plans for a nuclear strike were drafted but eventually discarded because it would have had a very negative effect on US standing in the world, and its military efficacy was also doubtful. Brinksmanship and nuclear threats thus failed to save the French. At the Geneva conference, Vietnam was divided in two along the 17th parallel with elections to reunite the country in two years’ time. The Americans decided to extend aid to the South Vietnamese government and thus began US military involvement in Indochina.

The next test for brinkmanship and nuclear threats was the Taiwan crisis of 1954–5. The US aimed to keep the Chinese guessing about their military intentions, and Henry Kissinger dubbed this the ‘uncertainty effect’. Mao Zedong also met brinkmanship with brinkmanship, but what the Americans did not fully grasp was that Mao was trying to draw the Soviet Union into a nuclear confrontation with the US. An example of this was in September 1954, when John Foster Dulles was flying to Manila for the formation of the South East Asian Treaty Organization (SEATO) – which involved the US, UK, France, New Zealand, Australia, the Philippines, Thailand and Pakistan – and China began shelling Quemoy and Matsu. Mao was aware that SEATO was to contain China.

In total, President Eisenhower was called upon to launch nuclear strikes five times:

- In April 1954, to aid the French at Dien Bien Phu; the argument was that nuclear weapons should be made available to the French;

- In May 1954, when France was on the verge of defeat;

- In June 1954, when rumours circulated that China was about to intervene in the Indochina War;

- In September 1954, when China began shelling the islands of Quemoy and Matsu;

- In November 1954, when long prison sentences were handed down to a dozen captured US pilots; Marshal Zhukov intervened at Eisenhower’s request and they were released.

On 23 November 1954, Dulles and the Taiwanese ambassador initialled a defence treaty between the US and Taiwan which included the Pescadores Islands, but it did not mention Quemoy and Matsu and other territories close to the Chinese mainland. It was inevitable that Mao would attempt to retake some of these small islands. On 18 January 1955, China invaded the Dachen and Yijiangshan Islands, not covered by the treaty, and the US reacted by evacuating Guomindang forces. But Mao ordered the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) not to fire at the Americans. Dulles hurled threats at the enemies of the US and, in February 1955, during a visit to Thailand, he stated the US was ready to go to war to counter the ‘expansionist aims and ambitions of China’. On 15 March 1955, Dulles warned that the US would deploy nuclear weapons to counter any new communist offensive, and it was not a paper tiger. President Eisenhower, the next day, thought that tactical nuclear weapons were no different from a bullet or anything else (Burr and Kimball 2015: 23–37).

Mao beat a hasty retreat and made it clear that China did not want war with the US. His aim had been to show China’s potential, and the crisis was put to rest. It had achieved its objective by placing the People’s Republic at the centre of world politics. Mao made Moscow fear that it might be drawn into a nuclear confrontation with the US, and this underlined Mao’s foreign policy strategy of creating tension with both superpowers simultaneously. Khrushchev complained to Mao that he did not understand Chinese policy. If the aim of shelling the islands was eventually to capture them, why was this not done? Khrushchev did not grasp that Mao did not want to take the islands but preferred to be able to shell them so as to create Taiwan crises in the future. He knew he could shell the islands with impunity whereas an attack on Taiwan would have provoked a massive US response.

After the first Taiwan crisis, Sino-American relations made little progress as China would only discuss the withdrawal of the US from Taiwan, and the US required China to renounce the use of force to solve the Taiwan question. There were 136 meetings between US and Chinese ambassadors (mostly in Warsaw) between 1955 and 1971, and the only agreement reached was to permit citizens trapped by the civil war to return home (Kissinger 2012: 160). It really was a dialogue of the deaf. One of the reasons for stagnant US relations with China during the 1950s was that the State Department was dominated by Soviet specialists – most Chinese specialists had left in the aftermath of the witch-hunt to discover who ‘lost’ China. The Soviet specialists were convinced that any rapprochement with China risked war with Soviet Union (Kissinger 2012: 200) – unfortunately, a false judgement.

Dulles was credited with inventing brinkmanship. He commented:

the ability to get to the verge without getting into the war is the necessary art. If you cannot master it, you inevitably get into a war. If you try to run away from it, if you are scared to go to the brink, you are lost.

(Life, 30 January 1956)

Dulles said there was a change under Eisenhower ‘from a purely defensive policy to a psychological offensive, a liberation policy which will try and give hope and a resistance mood within the Soviet Empire’. As regards communist dominated countries, the US must demonstrate that it ‘wants and expects liberation to occur’. He regarded containment as ‘futile, negative and immoral’. Churchill had a low opinion of his diplomatic skills (Mosley 1978: 65):

He is the only bull I’ve ever met who carries his own china shop around with him … he is a dull, unimaginative, uncomprehending, insensitive man. I hope he will disappear … he is a terrible handicap … he preaches like a Methodist minister and his bloody text is always the same … nothing but evil can come out of meeting [with the Soviets] … I am bewildered. It seems that everything is left to Dulles. It appears that the President is no more than a ventriloquist’s doll.

(Larres 2002: 310)

Nevertheless, Eisenhower thought Dulles was the best secretary of state the US ever had, but he had to reprimand him at times and told him not to use the expression ‘instant retaliation’ in his speeches. Eisenhower stated ‘peace is our objective and we reject all talk of and proposals of preventive war’. After Sputnik 1 the churches called for ‘massive reconciliation’ instead of ‘massive retaliation’. Dulles commented, in 1957, that there had been a shift in the balance of power in the world, and that shift had been in favour of communism. It should also be mentioned that Eisenhower thought he knew as much or even more than Dulles about foreign policy. Even though Dulles was normally bellicose about communism, he came to believe that a ‘peaceful evolution’ would eventually lead to communist states collapsing. Peace would result in their final demise, and he was right. When Dulles died he was succeeded, in April 1959, by the fragile Christian Herter.

Despite the bellicosity, Eisenhower’s strategy can be regarded as subtle and nuanced, resting on seven pillars (Ferguson 2015: 344–5):

- Feasibility of deterrence;

- The necessity of a secure ‘second strike’ capability;

- The abandonment of forcible ‘rollback’ of the Soviet Empire as a US goal;

- The recognition of the long-term character of the Cold War;

- The strengthening of US alliances in Europe and Asia;

- The pursuit of realistic forms of arms control;

- Bombing would not achieve these goals and had to be accompanied by diplomacy, psychological warfare and covert operations.

The key question, of course, was: would nuclear weapons be used in any conflict? Eisenhower did not believe that fighting a limited nuclear war was feasible because it would inevitably escalate, and there was also the point that US allies in Western Europe did not want any war to go nuclear for the simple reason that they would be wiped out.

General Douglas MacArthur, reflecting on the 1950s, commented (MacArthur 1965: 186):

Our government has kept us in a perpetual state of fear – kept us in a continuous stampede of patriotic fervor – with the cry of grave national emergency. Always there has been some terrible evil at home that was going to gobble us up if we did not blindly rally behind it by furnishing the exorbitant sums demanded. Yet, in retrospect, these disasters seem never to have happened, seem never to have been quite real.

A sobering comment by a top military man.

Moscow had always linked Germany and Austria and, in the latter, there were Soviet, US, British and French zones, and Vienna was divided into sectors. Shortly after Stalin’s death Khrushchev raised the question of Soviet troops leaving Austria, but Molotov strongly objected and as foreign minister ensured there was no progress for about two years. What forced Molotov’s hand? The imminent accession of West Germany to the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO). The Soviets did not want Austria and West Germany coming together to form a union (Anschluss) similar to that in 1938 so Molotov offered a peace treaty and withdrawal of forces if the country became neutral like Sweden or Switzerland and the peace treaty was signed in May 1955. There was another bonus for Moscow as neutrality meant that NATO forces could not move to Italy through Austria and would now have to go via France.

During an official visit, the Austrian chancellor, Julius Raab, handed a gift to Nikita Khrushchev, the Soviet Party leader. It was an original letter by Karl Marx providing information about revolutionary exiles in London, Paris and Switzerland. He received the equivalent of $25 for each missive. In other words, Marx was a paid agent of the Austrian secret service but there is no record of how Khrushchev reacted to this information.

This was the high point of Soviet détente at the time. Hopes were raised that a four-power meeting in Geneva, in July 1955, would resolve the German and other questions. Khrushchev was already top dog in Moscow but had no official state position to permit him to attend the summit. Bulganin was prime minister and formally headed the Soviet delegation. However, when Bulganin was asked a question, Khrushchev butted in and answered it, and this revealed who was now boss. Marshal Zhukov had pressed Eisenhower to attend, and he did, but the marshal was unusually sombre at the meeting. A reason for this may have been his discovery that the US had a plan – Operation Dropshot – which envisaged dropping 300 hydrogen bombs on Soviet targets and destroying 85 per cent of the Soviet Union’s industrial capacity. Dulles thought that Soviet power could be rolled back. The Geneva ‘spirit’ dissipated quickly as no progress was made on bringing East and West together, and the conclusion that Khrushchev drew was that the capitalists were as afraid of war as the Soviets. He told the French foreign minister that the whole of Germany would soon fall into the Soviet lap like a ‘ripe plum’. The Americans assessed Khrushchev as a leader who acted on emotion – a sharp contrast to the sober, calculating Stalin. Khrushchev, on the other hand, knew how far Dulles would go. In his memoirs, he says that the secretary of state was aware of how far he could push the Soviet Union and never went too far. An example was the Middle East crisis of 1958 involving Syria and Lebanon when Dulles stepped back from the brink of war. US and British troops pulled back, partly under the pressure of world opinion but also partly as the result of Dulles’s prudence.

Diplomatic relations were established between the Soviet Union and the Federal Republic of Germany in September 1955. The German chancellor, Konrad Adenauer, conceded that the Soviets would not agree to a united Germany. Why did Moscow agree to diplomatic relations? They needed German technology and know-how. The remaining German prisoners of war were repatriated, some choosing to go to the GDR.

Khrushchev liked to tell a joke about Adenauer:

Adenauer likes to speak in the name of the two Germanies and to raise the German question in Europe as though we couldn’t survive without accepting his terms. But Adenauer does not speak the truth. If you strip him naked and observe him from the rear, you can see clearly that Germany is divided into two parts. However, if you look at him from the front, it is equally clear that his view of the German question never did stand up, doesn’t stand up and never will stand up.

The first Soviet ambassador to Bonn was Valerian Zorin, who had masterminded the communist coup in Prague in February 1948, but he was so unsuccessful that he was withdrawn in July 1956. This indicated that there was no need to worry about a German-Soviet rapprochement which could lead to a German withdrawal from NATO. Bulganin and Khrushchev were invited to Britain in 1956, and the visit was a success.

Khrushchev is in a foul mood. He comes into the Kremlin and spits on the carpet. ‘Tut, tut’, says an aide, ‘that is uncouth behaviour.’ ‘I can spit on the carpet as much as I like. The Queen of England gave me permission.’ ‘How come?,’ asks the incredulous aide. ‘Well, I spat on the carpet in Buckingham Palace and the Queen said: “Mr Khrushchev, you can do that in the Kremlin if you wish but you can’t behave like that here.”’

The Geneva spirit led to the flowering of US-Soviet cultural exchanges with the Soviet pianist Emile Gilels and the violinist David Oistrakh delighting American audiences; Gershwin’s Porgy and Bess was staged in Moscow. The New York, Chicago and Los Angeles Symphony Orchestras gave concerts, and pianist Van Cliburn and violinist Isaac Stern wowed Soviet audiences. Igor Moiseev’s Folk Dance Company, the Beriozka Dance Troupe, and the Bolshoi Ballet toured the US.

Khrushchev’s Secret Speech at the 20th Party Congress, in February 1956, rocked communism in Eastern Europe to its foundations. He highlighted the dangers of unlimited power in the hands of one man which had resulted in Stalin dealing brutally with those who disagreed with him; he was capricious and despotic, and this was labelled the cult of personality. Foreign policy after 1945 resulted in complications for the Soviet Union because it was decided by one man. The Congress resolution underlined a new policy: peaceful coexistence, peaceful transition and peaceful competition, and thus a peaceful transition from capitalism to socialism was possible. The Secret Speech – so called because it was delivered to a selected group of delegates at the Congress – did not remain secret for very long. On 1 March, the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU) Presidium printed 150 copies of the speech, and Soviet embassies handed them to the Central Committee of the Communist Parties. The Polish Party printed copies, and a Reuters journalist was slipped a copy in March. Eventually, it was published by the CIA for worldwide consumption.

The speech caused consternation in Georgia (Stalin was Georgian). After the contents became known there was a mass wreath laying at Stalin’s statue in Tbilisi. Demonstrations grew and tens of thousands, carrying portraits of Stalin, demanded the resignation of Khrushchev, Malenkov and Bulganin and their replacement by Molotov. The demonstrations spread to all cities in Georgia and were, eventually, bloodily suppressed. At least a hundred were shot by Soviet Army soldiers in Tbilisi.

The release of tens of thousands of Soviet prisoners – many of them political – in 1956 added to the excitement in Poland. Violence exploded in Poznań, in June 1956, when factory workers came out and demanded higher wages and an end to food shortages; soon half the city was involved in demonstrations. Communist Party buildings were fired at and set on fire. The communist leadership ordered the military and police to shoot workers; over 150 died and hundreds of others were injured. One of the architects of the massacre was Józef Cyrankiewicz, the prime minister, who was a great toy collector – apparently, a whole room in his apartment was full of them, and he was said to spend hours playing with them. Cyrankiewicz, in the eyes of Edward Ochab, party leader from March to October 1956, was a weak man who had been broken during his time in Auschwitz.

Khrushchev, three members of the Soviet Presidium and the commander of Warsaw Pact forces, Marshal Ivan Konev, flew into Warsaw unannounced. When he saw Edward Ochab, he shook his fist under his nose and began screaming abuse. The Polish leader asked him not to make a scene at the airport and that everyone should repair to the Belvedere where foreign guests were received. Khrushchev wanted a plenum of the PUWP, the Polish Communist Party, which was to propose Władysław Gomułka as the new leader, cancelled. Ochab (reminiscing in 1981) told Khrushchev this was out of the question and that the plenum would go ahead.

I’ve spent a good few years in prison and I’m not afraid of it; I’m not afraid of anything. We’re responsible for our country and we do whatever we think fit, because these are our internal affairs. We’re not doing anything to jeopardise the interests of our allies, particularly the interests of the Soviet Union.

Khrushchev countered by saying that they’d come as friends, not as enemies. Ochab replied: ‘We don’t use such methods towards our friends … We’ll not back down … and Polish affairs will be decided by our Politburo.’ The Soviet leader complained that the Polish Politburo was taking decisions without consulting him. Ochab, rather cheekily, asked: ‘Do you consult us about the makeup of your Politburo or your Central Committee?’ Ochab described the discussions with the Soviet leaders as ‘bitter and difficult’ (Toranska 1987: 76).

Khrushchev ordered Soviet troops in Poland to halt their move towards Warsaw, and Gomułka warned Khrushchev that Poles would resist Soviet military intervention. The growing crisis in Hungary was also a contributory factor in staying the hand of Moscow. Mao, who shortly before had spoken of Soviet great power chauvinism, reported to a meeting of his Politburo that he had received a letter from the Polish leadership asking for help. ‘The relations between the USSR and Poland are no longer those between teacher and pupil. They are relations between two states and Parties.’ Mao summoned the Soviet ambassador to his bedroom (contrary to protocol) and told him: ‘We resolutely condemn what you are doing. I request that you immediately telephone Khrushchev and inform him of our view. If the Soviet Union moves its troops, we will support Poland.’

Khrushchev invited representatives of socialist countries, including China, to come to Moscow for consultations. It was logical for Mao to oppose Soviet military moves in Poland because if Khrushchev had used force and Mao had acquiesced, it would have set a precedent as Khrushchev could have used the same tactic to intervene militarily in China and remove Mao. The Great Helmsman again summoned the ambassador to his bedroom and told him that he was greatly displeased by Khrushchev’s anti-Stalin policy (Pantsov 2015: 179).

Gomułka managed to get compensation for additional coal deliveries, and he also succeeded in getting the Polish born Soviet Marshal Konstantin Rokossovsky (Rokossowski in Polish), minister of defence since 1949, to pack his bags and return to Moscow. On his return, despite having had eight teeth knocked out by the NKVD while under arrest in 1937, he refused to participate in Khrushchev’s anti-Stalin campaign. He commented: ‘For me, comrade Stalin is sacred.’

A decisive factor in allowing the Poles to choose their own communist leader was Gomułka’s promise to remain loyal to Moscow and the Warsaw Pact Organisation.

One of the reasons why the previous party leader, Edward Ochab, had failed was because he had fallen out with the Roman Catholic Primate of Poland, Stefan Wyszyński. The Primate had entered into a secret agreement with the communists in 1950, which permitted the Church to own property, separated Church and state and permitted the Church to select bishops from a list of three drawn up by the state. Wyszyński was arrested in 1953, and Ochab made the mistake of cancelling the agreement about the appointment of bishops. Gomułka was much cleverer, and he released the Primate and restored him to office. Wyszyński appealed to Poles to forget about heroics and lead a normal life. It was a remarkable tandem. Religious instruction was provided in schools on demand, masses were crowded and Poland became the most religious state in Europe with a new state-Church social contract emerging. How different things were in Hungary. When the Primate, József Mindszenty, was released from prison, in 1956, he sided with the insurgents and thereby fuelled the civil war.

Pax, from the 1950s, an official Catholic party, was represented in parliament, controlled its own press and publishing house, educated children and built many churches. From 1956, it was replaced by Znak which also sat in the Sejm and from which many oppositionists emerged, including Tadeusz Mazowiecki who became prime minister in 1989. From the 1960s onwards, the Church was permitted to engage in a huge construction programme of churches, seminaries and sanctuaries, unprecedented since the eighteenth century. The prevailing Modernism did not apply to ecclesiastical designs (Hatherley 2015: 192–3).

Poles hoped that the second coming of Gomułka would herald a new political, social and cultural dawn for the country. They were to be bitterly disappointed as Gomułka turned into a narrow-minded communist bureaucrat who dissipated the legitimacy he enjoyed in 1956. Initially, he got on well with the intelligentsia but gradually it resented the censorship and encouraged student revolts. The regime began to identify the Jewish origins of many of those involved and ugly anti-Semitism appeared; this was to result in the expulsion of many Jews in 1968. Gomułka, according to Ochab, was afraid of democratisation because it would open the door to ‘hostile elements’ (Toranska 1987: 84).

He simply had a nationalistic mania. But I’d never suspected he would go as far as an anti-Semitic campaign. Still, he shouldn’t be seen in an entirely negative light; you can’t judge him solely on the basis of his nationalistic mania, his autocratic aspirations, his lunacies – I think they were symptoms of a disease: megalomania and persecution mania. Such manias tend to flourish in the difficult circumstances in which our government is developing.

Ochab states that his disgust at the anti-Semitic campaign led to his resignation from all his party and state posts. He died on 1 May 1989, when communism in Poland was on its last legs.

Events in Hungary took a much more tragic turn in 1956. Both the reformers and conservatives looked to China for support but the embassy locked its gates and refused contact with everyone. When members from the former Rákosi government sought refuge, the doorman told them to go to the Soviet embassy.

Anastas Mikoyan had travelled to Budapest in July 1956 to insist that Mátyás Rákosi depart as communist leader, and Khrushchev had him flown to Moscow and put under house arrest there. Mikoyan also met and considered János Kádár as the new leader but Ernö Gerö was chosen. The Kremlin was aware that picking a Jew, Gerö (né Singer), to succeed another Jew, Rákosi (né Rosenfeld) would make it difficult for the party to win over the population. Gerö had spent much time in the Soviet Union and was regarded as a ‘Moscow’ communist, not a national communist, and Khrushchev later conceded that they had picked the wrong comrade. The party permitted the reburial of László Rajk, a former minister of the interior, who had been executed as a Titoist. Hungarians now regarded him as a martyr. On 23 October, thousands lined the streets of Budapest, and Rajk’s widow was told by Imre Nagy that Stalinism would soon be buried there too. Nagy, a popular prime minister from 1953–5, was readmitted to the party.

Liu Shaoqi and other members of the Chinese delegation flew to Moscow on 23 October and engaged in eight days of discussions with Khrushchev and other members of the Presidium. On several occasions, the first on 24 October, Liu and Deng Xiaoping attended Presidium meetings. Khrushchev explained to them that whereas the Polish crisis had been an intra-party dispute, the Hungarian concerned the overthrow of communist power.

Students issued a manifesto calling for Soviet troops to leave Hungary and ‘Comrade Imre Nagy’ to become prime minister. On 23 October, the huge Stalin statue which dominated central Budapest was toppled. Khrushchev instructed Gerö to appoint Nagy prime minister immediately but Gerö then made a hard line speech which infuriated many. Soviet troops and tanks moved into Budapest the next day and fighting broke out. Pál Maléter, a colonel in the Hungarian army, became the face of opposition to Soviet domination. Imre Nagy was appointed prime minister on 24 October and remained in office until 4 November.

On 28 October, the Kremlin ordered its troops out of Budapest to be replaced by Hungarian troops. It appeared that Khrushchev had conceded that a reform communist could run Hungary, and Maléter became minister of defence in a coalition government which included members from the reformed Social Democratic Party and Smallholders’ Party. This was a national government, and it also included János Kádár, the new leader of the Communist Party.

Mao did not comment on events until 29 October, when he phoned Liu and told him Moscow should loosen its grip on the Eastern European states and that peaceful coexistence should extend to socialist state to state relations. Also on 29 October, in consultation with Liu, Khrushchev agreed to draft a statement, which was to be published the next day, declaring full equality between the Soviet Union and Eastern European states. When the security situation became more desperate, Khrushchev and Liu changed their minds and agreed to resort to force, but Mao intervened and recommended that events should be allowed to ‘go further’; the Soviets then decided not to use force.

Anastas Mikoyan and Mikhail Suslov, in Budapest, approved the appointment of Kádár and the composition of the coalition government, but they were taken aback by Nagy’s statement that the government would begin negotiations with the Soviets to remove their armed forces from Hungary. Resistance fighters began hanging hated policemen and communists from lamp posts in Budapest.

On 30 October, the Soviet Presidium accepted the five principles of peaceful coexistence proposed by the Chinese:

- Respect for sovereignty and territorial integrity;

- Non-aggression;

- Non-interference in internal affairs;

- Equality;

- Peaceful coexistence.

This revealed that the Chinese view that the Hungarian crisis should be resolved peacefully had prevailed. The Soviet Party Presidium decided thereupon to withdraw all Soviet troops from Hungary and all socialist states and to work towards a peaceful solution. On the same day, the Soviet Presidium adopted a declaration which stated that ‘countries of the great community of socialist states can base their mutual relations only on the principle of … non-interference in one another’s domestic affairs.’ However, the situation changed dramatically, and Khrushchev changed his mind and declared: ‘troops will not be withdrawn from Hungary and Budapest and will take the initiative in restoring order in Hungary.’ On the evening of 31 October, as the Chinese delegation were at the airport en route to Beijing, Khrushchev and the Presidium explained the reversal of the decision to resolve the situation peacefully. The Chinese concurred that force was necessary (Pantsov 2015: 180–2; Shen and Xia 2015: 172–6). Hence in Poland and Hungary, China played an important role.

On 1 November, Kádár voted in favour of Hungarian neutrality as a member of the coalition government, but the same evening he flew to Moscow and was accompanied by Ferenc Münnich, a ‘Moscow’ communist. The next day, they met the Soviet leadership but not Khrushchev, who was in Eastern Europe briefing leaders on the reasons for the deployment of force. Kádár was unaware that the Soviets had picked him as the next Hungarian leader and told them that he had voted for neutrality and was against military force. On 3 November, Kádár changed sides and became Moscow’s comrade in Budapest and in doing so betrayed his own comrades. Because the Communist Party had lost all authority, he became prime minister. The Communist Party, eventually renamed the Hungarian Socialist Workers’ Party, would have to be rebuilt, and once that had been achieved he would again become party leader.

On 2 November, Khrushchev and Mikoyan flew to see Tito on Brioni to explain why they had decided to use force. Hungary was withdrawing from the Warsaw Pact and was to become neutral, but if Hungary left the ‘socialist camp’ Stalinists in the Soviet Union would receive a massive boost. Hungarian minorities in Romania and Slovakia, if Hungary became independent, would lobby to return to Hungary and thereby undermine the existing communist governments. There was a window of opportunity afforded by the Anglo-French attack on the Suez Canal which was then under way. Under this cover the Soviet Army could get away with using massive force. The Soviets misread the Suez attack, thinking it was American-inspired. As such, an invasion of Hungary could now follow to suppress the Revolution.

The intervention was wholly Soviet but it was packaged as a Warsaw Pact intervention. An ‘invitation’ was extended by the Hungarian coalition government and collective support came from other Warsaw Pact countries.

The suppression of the Hungarian Revolution took four days (4–7 November 1956); over 2,000 died and 20,000 ended up in hospital. Subsequently over 100,000 were arrested on ‘counter-revolutionary’ charges. Several hundred were executed. Over 100,000 fled Hungary and formed a Western diaspora which was not well disposed to the Soviet Union, to say the least. The communists were pleased to see them go.

Imre Nagy sought refuge in the Yugoslav embassy and was assured safe passage when he left the embassy on 23 November but was immediately arrested and taken to Romania. He remained under house arrest until 1958 when he was tried in Budapest and hanged. Maléter and another rebel were also hanged. It was long believed that these deaths were ordered by Moscow but this was not the case. It was Kádár who wanted the executions as he regarded Nagy as a dangerous political opponent. At his trial, Nagy stated that he knew one day there would be a new trial which would rehabilitate him and that he would also be reburied. He was remarkably prescient as all these things later occurred.

Communist regimes did adjust after 1956, and they introduced reforms which made contacts with the West easier. Vice President Richard Nixon was given an enthusiastic welcome in Warsaw in 1959, and there were even slogans such as ‘Long Live America’.

The events of 1956 proved that the Communist Party of the Soviet Union was still a Leninist party. It would shed the blood of workers to stay in power, and this reality had a profound impact on Eastern Europe. Violence would be ineffective against the regime, and opposition would have to be more subtle. If economic prosperity could be achieved, then dissent would have little impact, and this meant that the greatest threat to communist power would result from failure to raise living standards. There was severe repression in Hungary in the late 1950s as the communists strengthened their grip, and Kádár, a morose, miserable comrade at the best of times, turned out to be a suitable choice of a defeated nation. He and Yuri Andropov, who had been Soviet ambassador in Budapest in 1956, and later head of the KGB, got on very well. What a peculiar friendship! The story goes that Andropov’s wife was kept awake by the screams of prisoners being tortured which led to her suffering a deep depression.

In other parts of Eastern Europe, national communists dominated, and this was the case in Romania, Bulgaria, Albania, Yugoslavia and Poland. All the leaders wanted to have the power of Stalin and discovered that the best way to achieve this was to pose as saviours of their nation. As time was to show, Romania and Albania were to join Yugoslavia in distancing themselves from Moscow.

The suppression of the Hungarian Revolution had a dramatic effect on communism worldwide as droves of comrades in Europe and elsewhere abandoned the party. Some of those who left stated that they remained Marxists but were no longer communists. Those who remained demonstrated that they were willing to accept that Leninism – the use of brute force to suppress dissent – should not be revised.

The Polish and Hungarian crises had revealed divisions in the Soviet leadership, and the bill to maintain Soviet power in Eastern Europe was increasing by the day as Poland had to be given loans and Budapest had to be repaired. The other important lesson was that the West would not intervene militarily. The US had considerable strategic superiority but it was not aware of this at the time.

In July 1955, President Eisenhower announced that the US would launch an artificial earth satellite, but the Soviet Union got there first with the success of Sputnik 1 (meaning ‘fellow traveller’) in October 1957. It was an enormous propaganda coup for Moscow. Moscow was now ahead in space, and plans got under way to launch the first human in space. Sputnik was a tremendous shock, and a wave of near hysteria swept the US. The governor of Michigan expressed his dismay in verse (Andrew and Mitrokhin 2005: 6):

Oh, Little Sputnik, flying high

With made-in Moscow beep

You tell the world it’s a Commie sky

And Uncle Sam’s asleep

West Germany joined NATO in 1955, and in 1956 began to contemplate producing its own nuclear weapons. How would Khrushchev, in 1958 prime minister as well as First Secretary, respond? He returned to Stalin’s tactic: force the Western allies out of Berlin and thus began the second Berlin crisis. In November 1958, a note was sent to the Western allies accusing them of grossly violating the Potsdam Agreement on Germany; West Berlin was being turned into a mini-state, and this undermined the unification of Germany. The Soviet Union would transfer its occupation rights to the GDR, and West Berlin might become a Free City. The allies had to abandon West Berlin within six months. The US moved nuclear weapons to West Germany in such a way that the Soviet military mission in Frankfurt-am-Main, West Germany, could monitor events. The Americans also created a fleet of nuclear bombers which were permanently airborne and ready to strike when necessary. Khrushchev engaged in brinkmanship and thought the Allies would not go to war over Berlin, and his military told him it could take the city in six to eight hours. As during the crises in Poland and Hungary, Anastas Mikoyan was the voice of reason and encouraged Khrushchev not to provoke conflict. He was sent to Washington in January 1959, but nothing was achieved. Then the Soviet Union signed a peace treaty with the GDR.

Khrushchev and Eisenhower met at Camp David, Maryland, in September 1959, during his visit to the US. The US president was hoping to agree to a ban on nuclear testing and move towards verification but such was the mutual distrust that nothing came of these initiatives.

To President Eisenhower’s great relief, he was never called upon to sanction the use of nuclear weapons. As a soldier, he was aware that after the first salvo of nuclear weapons, there would be such devastation that the ‘fog of war’ would be such as to make planning for a second stage valueless.

In his memoirs, Khrushchev conceded that he had been forced to

economise drastically in the building of apartments, the construction of communal services and even in the development of agriculture in order to build up our defences. I even suspended the construction of subways in Kiev, Baku and Tbilisi so that we could redirect these funds into strengthening our defences and attack forces.

(Khrushchev 1971: 545)

Khrushchev was very impressed by American agriculture on his visit, especially the role of maize. On his return he ordered maize to be planted as the solution to the fodder problem. This earned him the nickname of Comrade Kukuruznik (‘Comrade Maize’), and he was lampooned far and wide.

The Soviets land on the moon. The Kremlin asks: ‘What do you see?’ ‘Well, there’s a short, bald man planting maize!’

The failure of maize was one of the reasons for his removal in October 1964. He gave the impression that the Soviet Union was ahead in rocketry, also in intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs), but this was a fiction and sooner or later the Americans would rumble him. Eisenhower was criticised for the ‘missile gap’ which had opened up with the Soviet Union. Khrushchev’s brinkmanship was based on false premises because he hoped that Soviet advances in rocketry would solve all his security problems within a few years. American overflights were aimed at discovering the real state of affairs but Soviet missiles could not bring them down.

On 1 May 1960, the US spy plane U-2 was shot down over Sverdlovsk (now Ekaterinburg). Captain Gary Powers was on a mission from Pakistan to Norway to photograph several highly sensitive nuclear sites in the Urals. At a height of 20,000 metres he felt safe, but three hours into the mission and over the Urals the autopilot failed. Instead of staying within the narrow speed and altitude ranges, it began pitching up and slowing down. Should he attempt to return to base or carry on? He decided to carry on. That meant another six hours flying, and he had to fly the aircraft manually and still operate the huge cameras under it.

The Soviets had no MiG aircraft which could fly higher than 17,500 metres but there was a new Sukhoi (Su-9) which was being delivered, unarmed, from the factory. One of the delivery pilots was ordered to fly the aircraft without pressure suit or helmet. ‘Your mission is to intercept the target and ram it,’ his commander told him – a suicide mission. The Su-9 climbed and attempted to approach Powers from the rear at Mach 2 (twice the speed of sound). The pilot was travelling about a thousand miles an hour faster than Powers, but he could not find the U-2. Ground control ordered him to cut his afterburner and he fell to earth. Two MiGs scrambled above Sverdlovsk but could not reach Powers, so the only hope now was to launch missiles. Three were fired but only one ignited and it took off the U-2’s tail and the wings also went. Powers went into a vertical spin. He managed to extricate himself and landed by parachute. He should have destroyed the cameras and the aircraft but he put his own safety first. Miraculously, he survived and the only person to die was a Soviet pilot who had been sent up to intercept Powers but had been hit by a stray Soviet rocket.

The Paris summit, which opened on 16 May, collapsed two days later, and Eisenhower’s proposed visit to the Soviet Union was cancelled. The U-2 incident dashed the hopes of a comprehensive Test Ban Treaty as the centrepiece of disarmament talks between the superpowers. It also ended the prospect of an end to the Cold War. President de Gaulle was personally affronted by Khrushchev’s behaviour and the failure of the Paris summit, and the outcome was that he turned away from the Soviet Union for five years and sided with the US on international relations.

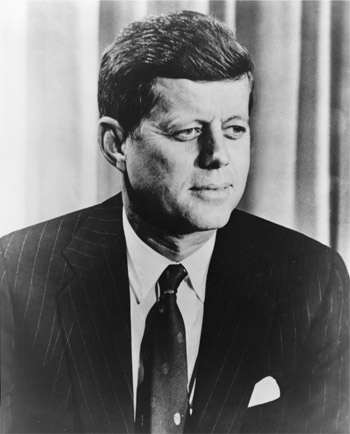

After Castro seized power in Cuba, a band of Cuban exiles was set up in Nicaragua and funded by the CIA. Eisenhower did not give them the go-ahead to attack Cuba, but under Kennedy they formed the core of the April 1961 attack at the Bay of Pigs. The president was informed by his Joint Chiefs of Staff that the invasion had a ‘fair chance’ of success. Kennedy assumed this meant it was quite likely to succeed while the chiefs actually meant it had a 25 per cent chance. Greater precision would have avoided this misunderstanding and prevented the fiasco which resulted.

Khrushchev deduced that Kennedy was a weak president, and the Bay of Pigs debacle revealed that he was not at all intelligent, and it followed he would wilt under pressure. Kennedy met Khrushchev in Vienna in June 1961 and came off second best. He was warned not to engage in polemics with a master such as Khrushchev but he failed to follow this advice. This strengthened Khrushchev’s resolve to force concessions in Berlin and, more daringly, in Cuba. Walter Ulbricht had been advocating stemming the tide of refugees to West Germany for some time, as socialism could not be built in the GDR if skilled personnel walked away. A wall was needed, and he had asked for one to be built at a Warsaw Pact meeting in March 1961 but was flatly turned down. Khrushchev eventually agreed, and the Berlin Wall went up on 13 August 1961 – the anniversary of the birth of Karl Liebknecht, one of the founders of the Communist Party of Germany (KPD). The Soviet leader did not think he was risking war, and to remind everyone of Soviet power, nuclear tests resumed. This underlined the fact that the Soviet leader believed nuclear threat diplomacy was effective and he had been practising it since the Suez crisis when he had incorrectly concluded that his threat to launch a nuclear attack on US bases in Britain had forced the Anglo-French pull out of Egypt.

The Western powers accepted the Wall but one dangerous incident did occur. On 27 October 1961, ten US and ten Soviet tanks faced one another at Checkpoint Charlie for sixteen hours. The reason was the refusal of the GDR authorities to allow a US diplomat access to East Berlin; he had insisted that he could enter without any passport checks. Khrushchev was attempting to end free access to East Berlin by the Western powers. Kennedy sent his brother, Robert, to inform a Soviet official that if the Soviets removed their tanks, the Americans would do the same within twenty minutes. Dean Rusk, secretary of state, instructed General Lucius Clay, the president’s personal representative in Berlin, that entry to Berlin was not a ‘vital interest’ and would not justify the use of force to ‘protect and sustain’ it. The next morning, the Soviet tanks withdrew, followed by the US tanks half an hour later. At the 22nd Party Congress, then in session, Khrushchev announced that he was withdrawing his Berlin ultimatum. The crisis revealed that Kennedy was willing to make concessions by back channel contacts to conceal from the public that he had backed down.

In November 1958, a secret military organisation, Live Oak, had been set up by the three Western military powers for the defence of Berlin. During the aforementioned crisis, they sent military vehicles along the autobahn to Berlin to discover if the GDR or Soviet authorities would interfere with the traffic. Had they done so, it would have led to escalation and possibly to nuclear war. From a conventional point of view, the Western military position in West Berlin was untenable, and the only way to defend the city was by deploying nuclear weapons. The West had made it clear that any attempt to blockade Berlin, as in 1948, would lead to escalation. General Clay, from his experience in 1948, was convinced that Khrushchev was bluffing and would not risk nuclear war; he turned out to be correct but no one could be certain, least of all the president. It was a baptism of fire for him and prepared him for an even greater test the following year. The Berlin crisis also confirmed in Kennedy’s mind that a limited nuclear conflict – for example, over Berlin – was not credible. A nuclear conflict would be all or nothing.

There were incidents in 1962 when Soviet aircraft interfered with flights to West Berlin. This led to the US sending jet fighters to accompany US aircraft. The second Berlin crisis can be said to have ended in October 1962. This was when the Cuban Missile Crisis was resolved, and this underlined the fact that the two crises were interlinked. Had Khrushchev got his way in Berlin and Cuba, the geopolitical map of the world would have been redrawn. NATO would have turned out to be a fig leaf, and Bonn would have been in Moscow’s pocket. The stakes for Kennedy were that high, and because of this the US was prepared to fight a nuclear war over Berlin and Cuba.

On 29 June 1960, Khrushchev received from the KGB an alarming piece of intelligence about US military intentions (Andrew and Mitrokhin 2005: 38).

The Pentagon is convinced of the need to initiate a war with the Soviet Union as soon as possible. Right now, the USA has the capability to wipe out Soviet missile bases and other military targets with its bomber forces. But over the next little while the defence forces of the Soviet Union will grow … and the opportunity will disappear … As a result of these assumptions, the chiefs at the Pentagon are hoping to launch a preventive war against the Soviet Union.

Khrushchev took this totally false analysis at face value and, on 9 July, warned the US that the Soviet Union had rockets with a range of 13,000 km and could defend Cuba if the Pentagon dared to intervene there. Raúl Castro, visiting Moscow later that month, conveyed Fidel’s gratitude for Khrushchev’s speech. Was this misleading report the genesis of the plan to place medium range missiles on Cuba?

On 29 July 1961, Aleksandr Shelepin, head of the KGB, presented to Khrushchev a grand plan to create circumstances in different parts of the world which would divert American attention and tie it down during the settlement of a ‘German peace treaty and West Berlin’. National liberation movements, armed by the KGB, were to launch attacks on ‘pro-Western reactionary governments’. Top of the list, together with Cuba, was the establishment of a second communist state in Nicaragua. The Frente Sandinista de Liberaciȯn Nacional de Nicaragua (FSLN), headed by Carlos Fonseca Amador, guided by the KGB and the Cubans, was to attempt this. A revolutionary front, headed by Cuba and Nicaragua and directed by the KGB, would become active in Latin America. The KGB was providing thousands of dollars through its embassy in Mexico City. Sandinista guerrilla groups were also being trained in Honduras and Costa Rica and other guerrilla groups appeared in Colombia, Venezuela, Peru and Guatemala. Peru became a disappointment because the most effective guerrilla group was the Sendero Luminoso (Shining Path) which was Maoist. This was a constant problem for Moscow as it battled to counter the appeal of the extreme left Maoists.

American advantage in intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs) was 9 to 1, and the Soviets only had twenty-five delivery vehicles to hit the US, but the Americans did not know this at the time. Because a Soviet ICBM could reach the US, the Cuban missile crisis was more about power and prestige than about missiles. The US had already stationed missiles in Turkey. It occurred to Khrushchev that if the Soviet Union could place medium- and intermediate-range nuclear missiles in Cuba, they could strike at many US cities. The CPSU Presidium accepted this in May 1962, and shortly thereafter a small delegation was sent to Havana to seek Castro’s approval. The latter commented later that had it only been about Cuba’s defence he would have rejected the missiles, but in a show of solidarity with the Soviet bloc he agreed. Khrushchev concluded that the Americans would accept the missiles if they were installed before the (mid-term congressional) elections in November. This was based on his own judgement as he had not requested an intelligence report on the likely reaction of the US. Anastas Mikoyan was unhappy, saying that the Americans would never tolerate it and he, as usual, had a better nose for superpower relations. He was to prove, as in domestic policy, the voice of reason who had to rein in the wild risk-taking of the First Secretary.

In April 1961, the Americans had attempted in the Bay of Pigs to overthrow Castro’s regime; Moscow thought they would try again and they were right. It was called Operation Mongoose. Secret Operation Anadyr was launched, and even the Soviet ambassador in Washington was not informed. Five missile regiments with modern medium-range missiles were dispatched; about 42,000 troops were involved. Soviet ships docked 183 times to deliver 23,000 tonnes of military ordnance. In October, Soviet troops had 152 nuclear missiles as well as Ilyushin Il-28 bombers and the most modern nuclear submarines armed with submarine-launched ballistic missiles (SLBMs) as well as nuclear torpedoes. The Americans only discovered the arsenal on 15 October as a result of U-2 overflights, and it would have taken longer if the Soviet troops had thought of camouflaging the launch sites. The Soviets, therefore, had carried out a brilliant secret mission under the noses of the Americans. President Kennedy found himself confronted with a painful dilemma: accept the presence of the missiles, bomb the sites or negotiate them away. His military favoured a surgical strike, but when he asked if they could guarantee 100 per cent success, they were silent. Kennedy rejected a military in favour of a diplomatic solution. Nevertheless, SAC had 912 bombers on fifteen-minute ground alert with every bomber carrying three or four thermonuclear bombs. By early November, when the crisis was abating, SAC had increased the number of bombers on alert from 652 to 1,479 and nearly 3,000 nuclear weapons were ready for launching. One hundred and eighty-two ICBMs were ready to be fired as were all 112 Polaris missiles. Soviet bomber and missile forces were also on high alert. Both sides threatened massive retaliation.

On 22 October, Kennedy demanded that Khrushchev remove the military installations and return the missiles to the Soviet Union; on 23 October he discussed an all-out nuclear exchange with his advisers; on 24 October he announced a quarantine of Cuba; on 24 October DEFCON (Defense Readiness Condition) 2 was set in motion – this was one step from imminent nuclear war. On 25 October, Soviet ships heading for Cuba were turned back, and the US placed a quarantine zone around the island. The most dangerous day was 27 October, when everything could have gone pear- or rather plume-shaped when a Soviet submarine almost fired a nuclear torpedo. On the same day, a U-2 reconnaissance aircraft drifted into Siberian airspace in error, and Soviet MiGs were scrambled to shoot it down; fortunately F-102As got there first and guided the US plane safely to Alaskan airspace. Had the MiGs shot it down, the Soviets might have interpreted it as the last reconnaissance flight before American missiles rained down on the Soviet Union.

On 28 October, Khrushchev announced, after a secret exchange of letters, that the missiles would be transported back to the Soviet Union. Kennedy agreed not to attack Cuba and to withdraw US missiles from Turkey, but the latter part of the deal was not to be made public.

Khrushchev did not need to judge whether Kennedy was bluffing or not. As the Soviets had broken the American codes, he could read all American communications, and when he found out that Kennedy had placed US forces worldwide on full alert – one step from going to war – he was shocked and gave in.

Castro was not involved in the negotiations and learnt of the climb down from the radio. When an official reported what he had heard, it took Castro about five minutes to take it in. He berated the Soviet leader as a ‘bastard, an idiot without balls and a homosexual’. To say that the Cuban leader was livid would be an understatement. The KGB chief in Havana warned Moscow that ‘one or two years of especially careful work with Castro will be required until he acquires all the qualities of Marxist-Leninist Party spirit’ (Andrew and Mitrokhin 2005: 40–6). The volatile Cuba leader was proving a hot potato for Moscow to handle and would increasingly become so in the future.

Anastas Mikoyan, the comrade for all seasons, was dispatched to explain to Castro that the decision had been right. Mikoyan was not the only one who thought that the world had been a hair’s breadth from a Third World War. The experience exposed the danger of the lack of direct links between Moscow and Washington, and the telephone hotline was the result.

On 2 November 1962, Gervase Cowell, an intelligence officer in the British embassy in Moscow, received a phone call. The call consisted of three short blows of breath, and a minute later the phone rang again. Once more there were three short blows of breath. Cowell was the officer who was running Colonel Oleg Penkovsky, one of the most important Soviet agents ever recruited. The calls were the prearranged signal to announce that a Soviet nuclear attack on the West was imminent. At the time Britain’s nuclear armed V-bombers were still on high alert.

What did Cowell do? He pondered and then did nothing! He did not even inform his ambassador or London, as he concluded that Penkovsky had been arrested (he had been taken on 22 October) and that the information had been beaten out of him. What an extraordinary stunt to pull! Did Khrushchev give the go ahead? Had Cowell misjudged the information, the sky could have been black with nuclear missiles. What would have happened had a CIA officer received the call? It does not bear thinking about.

It is now clear that the Berlin crisis and Cuba were linked (as were Vietnam and Laos). On 16 October, Dean Rusk, US secretary of state, commented that ‘Berlin is … very much involved in this … for the first time. I’m beginning really to wonder whether maybe Mr Khrushchev is entirely rational about Berlin’ (International Security, Vol. 10, no. 1, 1985:177).

In January 1963, a joint US-Soviet note to the UN Secretary-General officially ended the Cuban conflict. Both the US and USSR concluded, on the basis of the Cuban crisis, that nuclear war would devastate their countries. On 20 June 1963, a hotline was established between the US and the USSR. During the crisis, it had taken Washington up to twelve hours to receive and decode a 3,000-word message from Moscow. By the time Washington had drafted a reply, a tougher message from Moscow had arrived, and this made for confusion. The hotline was never a telephone line. At first, teletype equipment was used, then replaced by facsimile units in 1988 and since 2008 by a secure computer link over which messages are exchanged by email.

What impact did the Cuban crisis have on the average American? Tom Hanks, in Bridge of Spies (2015), plays James Donovan, a lawyer who defends Rudolf Abel, a Soviet spy later exchanged for Gary Powers. He reminisces:

I was six and I remember the way every adult I knew was carrying around this thing, which was fear. I didn’t know the world was any bigger than Redding, California, but it was the beginning of this reality that carried right through to the 1970s – that the Third World War was inevitable, round the corner. It could be staved off for a while, but not for ever – and we might lose.

(The Sunday Times, 15 November 2015)

Khrushchev loved travelling. In 1963 he spent almost half the year away from Moscow and, in 1964, an astonishing 150 days abroad. His opponents struck when he was on holiday at Pitsunda, on the Black Sea, on 12 October 1964. He received a phone call from Leonid Brezhnev and was summoned to a meeting of the Central Committee which was to discuss agriculture and ‘some other matters’. He had been told by his son, Sergei, that there was a plot under way but had given it little thought.

No one met him at the airport – ominous. Furious, he rushed to the Kremlin and barged into the room where the Presidium was in session. ‘What’s going on here?,’ he thundered. ‘We’re discussing Khrushchev’s removal from office,’ Suslov calmly replied. ‘Are you crazy? I’ll have you all arrested here and now.’ Khrushchev stormed out of the room and rang Marshal Rodion Malinovsky, the minister of defence. ‘As Commander-in-Chief I order you to arrest the conspirators at once.’ Malinovsky countered that he would only carry out the orders of the Party Central Committee. Rebuffed, Khrushchev then rang Vladimir Semichastny, chair of the KGB. Again he declined, stating that he was bound to carry out the orders of the Central Committee.

Who stood to gain most from the removal of Khrushchev? Leonid Brezhnev and Nikola Podgorny: the latter became president of the Soviet Union when Brezhnev became the new First Secretary. According to Vladimir Semichastny, head of the KGB, Brezhnev had proposed the assassination of the First Secretary on several occasions. A car or plane crash could be arranged. Semichastny avers that he rejected all these suggestions.

There were many accusations:

- Khrushchev had tried to develop a new cult of personality.

- He had ignored the elementary rules of leadership, giving his colleagues insulting, obscene names.

- He had presided over the economic decline of the country; labour productivity was down.

- The US was economically further in front than ever.

- Five-storey apartment blocks were less efficient than 9–12 storey blocks.

- Twenty years after the war, agriculture was in such a mess that ration cards had to be reintroduced and 860 tonnes of gold sold to import food from capitalist countries, and living standards in the countryside had not improved.

- Economic aid to the Third World was a failure; Guinea received considerable Soviet investments but ‘we were pushed out’; in Iraq, the Soviet Union was involved in over 200 projects; despite this, the new leader was an enemy of the Soviet Union and communists; the same happened in Syria and Indonesia; large amounts of aid and arms were sent to India, Ethiopia and other countries.

- He banged his shoe at the United Nations.

- He turned his son-in-law, Aleksei Adzhubei, whom he had made editor in chief of Izvestiya, into his unofficial foreign minister.

- He was guilty of adventurism (high risk-taker) in foreign policy and had brought the country to the verge of war on several occasions: during the Suez crisis the Soviet Union was within a hair’s breadth of war; on Berlin he issued Kennedy an impossible ultimatum to make Berlin a ‘Free City’: ‘we are not foolish enough to think it is worth starting a war to make Berlin a Free City’; the Cuban missile crisis forced the country into a shameful retreat.

- He called Mao Zedong an ‘old boot’ and Castro was a ‘bull who would charge any red flag’; he threatened to drive foreign opponents ‘three metres into the ground’; he told the West German ambassador: ‘We’ll wipe all you Germans off the face of the earth.’

- He was ignorant, incompetent, caddish and an adventurer in domestic and foreign policy.

(Pikhoya 1998: 212–14)

Kissinger has characterised Khrushchev’s foreign policy as that of the quick fix: the explosion of a super-high-yield thermonuclear device in 1961; the succession of Berlin ultimata; the Cuban Missile Crisis in 1962. His aim was to achieve a psychological equilibrium in negotiations with a country that Khrushchev, deep down, knew was considerably stronger (Kissinger 2012: 162).

The death of Stalin in 1953 resulted in a deep exhalation of breath by the literati. The conformity and fear of the Stalin years now gave way to reflection about the past and why writers and the population had remained silent. The first breakthrough novel was Ilya Ehrenburg’s The Thaw (1954), which gave its name to the first part of Khrushchev’s dominance of Soviet politics. It relates the story of a tyrannical ‘little’ Stalin boss and his wife’s voyage from conformity to eventually leaving him. The spring thaw symbolises the thaw in cultural life but also her emotions. Ehrenburg, a prolific wartime author, went on to write several other novels and memoirs. The diversification of culture and language undermined the staid conformity of the Stalin era. Uniformity, coherence and apparent stability would never be the same again. Terms such as sincerity and genuine, prevalent in the 1920s, were again discussed passionately. The more conservative elements in the literary hierarchy took umbrage at the pace of change, and a vigorous debate unfolded in the most popular journals, with Novy mir publishing the new wave and Oktyabr the traditional perceptions. A startling move was to publish Alexander Solzhenitsyn’s One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich in Novy mir in 1962 (his whole sentence is treated as a day because each day was the same). It brought the experience of the camps (gulags) to a wide Soviet and international audience. It was a sensation and, even more surprising, its publication had been personally approved by Khrushchev.

Soviet cinema began producing entertaining films, and one won the Palme d’Or at the Cannes Festival in 1958. Ballet was a Russian passion; the greatest ballerina was Maya Plisetskaya, but she was under a cloud in the post-war years because she was Jewish. Her father, a dedicated communist, had been executed in the purges, and her mother was sent to the gulag. Her interpretation of the Dying Swan (by Saint-Saëns) was enough to bring tears to anyone’s eyes. She danced for Stalin and Mao Zedong at the Bolshoi on the occasion of the dictator’s seventieth birthday, and as the daughter of a disgraced family, she was afraid to look Stalin in the eye. She reappeared in Swan Lake (by Tchaikovsky) at the Bolshoi in 1956. After the first act, the audience exploded. The KGB tried to dampen the enthusiasm and dragged members of the audience out screaming, kicking and scratching, but after the performance the KGB retreated and conceded defeat to the exultant audience. She was then permitted to travel abroad in 1959 and was feted worldwide. She always returned to Moscow despite pleas by her Western friends to defect. She confessed that, of all the great theatres in the world where she had performed, she loved the Bolshoi the most.

Fashion made a comeback during this period. Normally there were no dresses on sale, only material, so girls had to make their own dresses. This gave rise to a semi-independent clothes industry based in seamstresses’ homes. Designs were inspired by Western films and magazines. I was always struck by how well girls were dressed in Moscow and how badly men were attired.

The Virgin Lands scheme, launched by Khrushchev to increase grain output, was a Komsomol project – over 300,000 volunteers were mobilised – mainly in northern Kazakhstan and western Siberia in 1954. Conditions were so primitive that many of them returned home. ‘It seemed that if we did a little bit more, and a little bit more, we would find ourselves in paradise,’ the pioneer Viktor Mikhailov remembered. ‘We thought we were bringing the future to this country.’ Tens of thousands of students, soldiers, lorry and combine harvester drivers, and equipment were transported there annually on a seasonal basis. A combine harvester brigadier commented:

We didn’t have enough machinery. We started harvesting in August and stopped when the snow came. Then we tried to complete the work in spring. Sometimes we just piled the grain up in the fields. Not enough lorries and no roads.

(Swanson 2008: 131–2, 142)