The US regarded colonialism as a phase of history when European powers ruled the world. The European colonial powers in 1945 were a ragged bunch clinging to America’s coat-tails to survive the coming onslaught from communism. The Dutch had to be forced out of what became Indonesia (speaking Dutch was banned); the French, bedraggled and defeated, were quitting Indochina; but the British had the willpower to confront and defeat the Malayan communist insurgency which began in 1948. When India was granted its independence in 1947 it was inevitable that Britain would quit Asia.

So post-1945 became the post-colonial era. But how did the new states view themselves and what form of government and economy would they choose? They all shared one burning ambition: to throw off the shackles of colonialism and take control of their own destiny. Their cultures and traditions were now to flourish without alien influences.

There were two great development models: the American and the Soviet. Could the Third World come up with its own model? The American model was capitalist and thereby based on market competition; the Soviet model eliminated the market and was predicated on planners replacing the market.

The American model

- Urban-based growth in both the private and state sectors;

- Import of advanced consumer goods and the latest technology and become part of a global capitalist market and alliance with the world’s number one state;

- Democracy, involving a multi-party system;

- A free press and the rule of law;

- Secure property relations needed to protect ownership;

- Law of contract to promote business activity and enforce contracts;

- Independent courts to adjudicate disputes.

The main drawback of this model was the perception of post-colonial elites that the US was replacing the former European colonial powers. Another was that the post-colonial states did not want to become dependent on the US as their goal was to become successful independent states, choosing alliances whenever they gauged them advantageous. Another downside is that capitalism promotes inequality, as those who innovate swim to the top and inevitably acquire political influence. Foreign corporations tend to work with enterprising locals, and they then form an elite, leaving the vast mass of the population behind. The argument is that capitalism promotes economic growth and that the fruits of this trickle down to those below. This takes time, but locals wanted a tangible increase in their living standards immediately.

The Soviet

- Politics dominated by a single Communist Party which would promote economic growth through central planning (annual and five year plans, etc.)

- Mass mobilisation would provide the labour force for rapid economic transformation

- Emphasis would be placed on heavy industry (steel, iron, machine building, energy, etc.) and light and consumer goods industries would receive less investment;

- The resources for investment would come from depressing living standards in the short term and loans from Moscow;

- Huge infrastructural projects would advance the economy;

- The planned economy would operate according to prices set by planners and would not be subject to the market (supply and demand);

- Trade would be promoted with communist states;

- Soviet and Eastern European specialists would help to develop the economy;

- The military, police and security services would be trained by the Soviets and Eastern Europeans;

- All the necessary equipment would be supplied;

- The goal of social justice would be achieved because the means of production (factories, land, etc.) would be owned by the people (in reality, the state);

- Some African leaders thought that capitalism was too complex for their fledgling states and favoured a centrally directed, non-market model;

- Private trade would gradually be taken over by the state.

A major disadvantage was that the Soviet Union was viewed as less developed economically than the US; its consumer and investment goods were regarded as inferior to American and other Western products; the exception to this was the military sector.

Common to both models was the emphasis on education and science and technology. Knowledge-based growth would be accorded a high priority.

After independence, many leaders were attracted to the Soviet model (such as Indonesia and India) because it concentrated political and economic power at the centre and promoted the emergence of a dominant party. New elites could form around a dominant leader who would act as a patron, and political and economic decision making would be concentrated at the centre. The Soviet experience revealed that once a leader was in place he was there for life or when someone overthrew him. There was no mechanism for an orderly succession (China introduced one after Mao’s death). The Soviet model was particularly attractive in Africa where tribes are the dominant form of social grouping. A dominant leader from a minority tribe could emerge and legitimise his rule by arguing that he was promoting social justice and modernisation. A Marxist analysis is based on class, but some African states (e.g. Tanzania) pointed out that there are no classes there. There is only the tribal chief and his subjects. The Soviet model was based on heavy industry as the key to economic growth. The drawback here was although African was rich in raw materials, they had not been exploited. So, in the short term, they would have to be imported. A machine building industry needs to be built up to manufacture the equipment for heavy industry, so a cadre of skilled engineers has to be trained in communist countries.

India is an interesting case study. Jawaharlal Nehru, Indian prime minister from Indian independence in 1947 to 1964, studied law at the University of Cambridge and was influenced by George Bernard Shaw and other socialist intellectuals who belonged to the Fabian Society. Nehru set out to implement Fabian socialism in India. It involved the nationalisation of the steel industry, transport, electricity generation and mining. Private economic activity and entrepreneurship were discouraged and property rights downplayed. Economic life was dominated by state planning, licences were issued to regulate work and taxes were high. One of the results of this socialist experiment was that India’s share of world trade slumped and abject poverty was a feature of Indian life. It was only in the 1980s that free market reforms were introduced and the Indian economy then began to grow rapidly, lifting many out of poverty. Many Indian leaders were educated at British universities where socialist – often Marxist – economics was in vogue. This applied to other leaders of the Third World who had been educated in Britain such as Julius Nyerere, president of Tanzania from 1964 to 1985, who also implemented Fabian and African socialist ideas. He had read economics and history at the University of Edinburgh. He enforced collectivisation, and when peasants resisted, he burnt down villages. The result was economic decline, corruption and food shortages. When Tanzania tried market economics, it recorded impressive growth: gross domestic product (GDP) rose 40 per cent between 1998 and 2007.

Kwame Nkrumah studied at the London School of Economics where socialist economics was dominant. On returning to Ghana, he rushed through ‘forced industrialisation’, complete with state enterprises and ten-year plans. The inevitable result was low growth, corruption and heavy debt. Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, at various times president and prime minister of Pakistan, studied at the University of California, Berkeley and Oxford. Once he had gained power, he declared that ‘socialism is our economy’ and began nationalising the steel, chemical, cement and banking industries along with flour, rice and cotton mills. Economic growth plummeted. British academics, therefore, bear some of the responsibility for the poor economic performance of former colonies. An exception to the rule is Lee Kuan Yew, who studied at the University of Cambridge and the London School of Economics. When he returned to Singapore, he rejected the socialist economics he had imbibed and built one of the most successful economies in the Third World.

The International Monetary Fund (IMF) provides funds to governments which have short-term liquidity problems. The World Bank invests in infrastructural projects. Both institutions are based in Washington and are controlled by the US. The head of the World Bank is always an American, and the IMF is always headed by a European, usually French. The IMF provided resources for France and Portugal to resist challenges in their colonies, and without these funds, decolonisation would have begun earlier. In the new Third World states, the World Bank and IMF favoured those states which adopted the American model. They became powerful instruments in the hands of the US and often influenced private bank lending as well. When the US left the gold standard in 1971, it became easier for Third World states to access loans. The rapid rise in oil prices after 1973 made more funds available as the oil-rich states sought to invest their new-found wealth, but the Third World fell into the trap of accepting cheap loans and gradually became heavily indebted. US banks were happy to lend to Third World states assuming that Washington would bail them out if these states defaulted on their debts. The newly independent states were often dependent on exporting raw materials, but prices fell as technology advanced. The US aim was to create an international environment which promoted convergence between communism and capitalism, but the opposite occurred. Hence US policy made it more difficult for developing states to raise living standards as so much wealth had to be used to service debt. This, inevitably, contributed to the growth of left-wing movements.

US aid was always based on political and military criteria. Israel was top of the list for US aid – this was a far cry from 1948 when Czechoslovak arms, agreed with the Soviet Union, had been of critical importance in the foundation of the state. The Israelis declared an ‘unbreakable alliance with our great friend and the defender of mankind – the Soviet Union’. This changed very quickly and, a year later, Zionism was declared to be an imperialist plot to subvert the Soviet Union (Andrew and Mitrokhin 2005: 222–3). Zionism continued to be seen in this light until the late Gorbachev era. As regards US aid, Egypt was second only to Israel. Then came sub-Saharan Africa and South Vietnam.

The difficulties of constructing new, post-colonial states led to considerable instability in the Third World in the 1950s and 1960s. New leaders found themselves under attack from the left, often from Marxist movements. Marxism proved very attractive in Africa especially in Portuguese colonies (Mozambique, Angola, Guinea-Bissau and Cape Verde), Zimbabwe and South Africa.

The First World was not as powerful as it thought. The Third World discovered that it had something which was crucial to the development of advanced economies: oil. The power of oil as a weapon was revealed in 1973. OPEC (Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries) was set up in Baghdad in 1960 and consisted of Third World oil producers. It was an attempt to compete with the ‘seven sisters’, the powerful Western oil companies. After the US came to the rescue of Israel during the Yom Kippur War of October 1973, Saudi Arabia used oil to reset global politics. Angered by Israeli’s successful counterattack and push into Arab territory, Riyadh announced a complete oil embargo against the US. To ensure that Washington felt economic pain even if oil slipped in through the back door, Saudi Arabia – followed by the OPEC cartel which it dominated – cut production ultimately by 25 per cent, and between September 1973 and March 1974 the oil price quadrupled. Sheikh Yamani, the Saudi Arabian oil minister, declared: ‘What we want is a complete withdrawal of Israeli forces from occupied Arab territories and then you will have the oil.’ The Saudis thus launched what became known as the ‘oil weapon’. Henry Kissinger, US secretary of state, referred to these démarches as ‘political blackmail’ and as the ‘most important of our century’. The Saudi oil minister spelled out the geopolitical implications by referring to a ‘new type of relationship’ where ‘you have to adjust yourself to the new circumstances’. The US secretary of state adjusted, Israel retreated back east of the Suez Canal and the embargo was lifted, but global politics would never be the same again. Saudi Arabia, as the swing producer, had demonstrated that it possessed the power to drive up inflation and break economies, regardless of politics in the West. That threat has been Saudi Arabia’s entry pass to the global political stage, and it is still there today, but that entry pass is only valid as long as Riyadh is the swing producer. It was the first time that a group of relatively weak states had provoked such dramatic changes in the lives of the vast majority of people on the planet. The consequence eventually was a world economic crisis, but the raising of the oil price was only one factor. The US had abandoned the gold standard in 1971, and as a consequence the Bretton Woods system collapsed. Thereby the long period of economic growth in the developed world ended. In West Germany driving was banned on Sundays, and the autobahn was given over to pedestrians and cyclists. GDP there fell by 1.5 per cent, and unemployment climbed above one million.

The sharp rise in the oil price spurred research into alternatives, and nuclear power was promoted. This aroused considerable opposition because it was associated with the Cold War. The Iranian Revolution of 1979 cut the amount of oil available on international markets, and in 1981, the price of a barrel rose to $41 and kept on rising. As a result, Western Europe turned to the Soviet Union for oil. It was bonanza time for Moscow, and the Soviets became more and more reluctant to export oil at low Comecon prices to Eastern Europe. One estimate puts the Soviet subvention to the region in the ten years after 1973 at $118 billion, and this covered oil and other raw materials. The GDR, for example, exported the cheap Soviet oil and gas to Western markets at a handsome profit and, needless to say, the Soviets were not amused. In January 1989, a GDR delegation travelled to Moscow to ask for an extra two million tonnes of oil on top of the seventeen million expected. The Soviet leadership regarded this as brazen cheek and threatened to deliver less than seventeen million. The oil producing Gulf States and Saudi Arabia amassed huge dollar reserves, and per capita income was above that of the US. However, the vast wealth did not trickle down, and the average Arab remained poor.

The downside of the oil bonanza for the Soviet Union was that it put off the need to launch economic reforms. It was at precisely this moment that the Soviet economy began to decline, but this was only realised later. The high oil and gas prices halted necessary reforms for a decade.

After Stalin, Soviet leaders resolved to deal with Third World states at the level of government. Sukarno’s Indonesia, Nasser’s Egypt and Nehru’s India were high on the list of priorities. Why? They were viewed as anti-Western and radical. Khrushchev’s first important foreign trip was to Beijing in 1954, and he went on to Burma (Myanmar), India and Afghanistan the following year. The welcome in India was so effusive that crowds almost crushed him to death. Everywhere he stressed the Soviet Union’s willingness to cooperate with non-socialist countries economically and militarily, and their common enemy was colonialism and imperialism. Stalin’s view of the Third World was blinkered, but now Moscow should reach out to non-socialist parties and national movements. New institutes for the study of Africa and Latin America were set up, and the KGB and GRU (military intelligence) were to roam the Third World collecting useful information.

In 1960, at the United Nations, Khrushchev talked up the alliance with national liberation movements as the best way to spread communism around the world. Together with the Soviet Union, a bright economic future beckoned. Sputnik 1 had shocked the Americans and astonished the world, and Yuri Gagarin was the first man in space in 1961. Social revolution was like an irresistible tide which would drown capitalism and lead to global communism within a generation. The self-confidence of the Soviet Union was boundless. How would the US respond? (Westad 2005: 66–72).

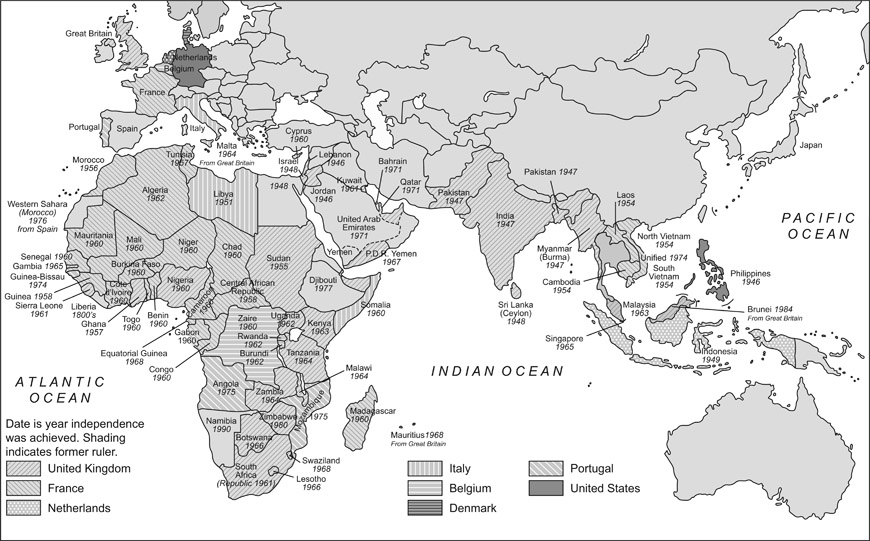

Map 4.1 Decolonisation in Africa and Asia since 1945

Both Moscow and Washington competed to attract Third World states to their side. They regarded it as a zero sum game: a country which joined the other side was a loss, but many Third World states did not wish to become embroiled in Cold War politics and preferred to forge their own identities. Could they reject East and West and, through solidarity, become a force in the world? Five Asian states – Indonesia, India, Pakistan, Burma (Myanmar) and Sri Lanka – launched an initiative which grew into the largest gathering of Asian and African countries ever assembled; they convened in Bandung, Indonesia, in April 1955. France had just been evicted from Indochina, and many African colonies were on the road to independence. Twenty-nine countries were represented, including the People’s Republic of China, but the Soviet Union was not invited although most of its territory lay in Asia. They counted 1.4 billion people, over half of the world’s population, and the goal was to articulate a common ideology which would supersede capitalism and communism. Sukarno, the Indonesian leader, spoke of fusing nationalism, Islam and Marxism into a new moral ideology. Morality, he claimed, was better understood by Third World countries because they had suffered the indignities of colonialism. Jawaharlal Nehru, the Indian prime minister, rejected the efforts of Iraq, Iran and Turkey to label Soviet control of Eastern Europe as colonial, and Zhou Enlai promoted peaceful coexistence and non-alignment. The meeting did not endorse the armed struggle of the national liberation movements but called for an end to apartheid in South Africa and support for Palestine.

The Bandung conference was viewed with mounting distrust in Washington. The Third World was moving left, and Dulles even thought of organising an anti-Bandung conference of pro-Western states but dropped the idea quickly. Nikita Khrushchev warmed to the prospect of declining Western influence, but the desire for independence worried him as this would make it more difficult for the Soviet Union to promote its agenda in the Third World as local Communist parties might be seen as taking orders from a foreign power. He was further disconcerted by the meeting on Brioni Island, Yugoslavia, of Nehru, the Egyptian leader Nasser and Tito. Khrushchev was aware that Tito had no intention of ever subordinating himself to Moscow. A nightmare scenario would be hordes of Titos running the Third World.

What about economic cooperation after Bandung? It turned out to be very disappointing. Why was this so? One reason was that Third World countries had complementary economies – they wanted to export primary products and import technology which was best sourced from the First World. Another difficulty was the lack of credit available to trade among themselves as Western banks concentrated on promoting trade between the Third and First Worlds. Third World states favoured barter agreements among themselves because they had so little hard currency.

In September 1955, Nasser signed an arms deal to procure large quantities of Soviet arms via Czechoslovakia. This move came as a tremendous shock to the West. The KGB made Nasser aware of British plans to assassinate him just before the Anglo-French attack on Suez in October 1956. The crisis brought home to Third World countries the need to procure military hardware, and the main source was the Soviet Union and its Eastern European satellites. Nasser began supporting the armed struggle in north Africa much more directly and, in Algeria, the Front de Libération Nationale (FLN), the national liberation movement, was recognised as a de facto government by much of the Third World.

In the 1960s, the New Left in Europe, harbouring guilt for Europe’s imperial past and present, began to identify with national liberation movements which promised a new, exciting future for those involved. It also promised to undermine the bourgeoisie in the West. They saw the Third World as the future, many Americans joined this bandwagon and the Soviet Union was viewed as conservative and having lost its revolutionary teeth.

Algeria became independent in 1962 after eight years of bitter civil war which cost the lives of a million Muslims and led to the expulsion of about the same number of French settlers (les pieds noirs). Ahmed Ben Bella, its leader, became the spokesman for the Third World. China recognised the FLN in 1958 and the Soviet Union in 1960. The pro-Soviet Algerian Communist Party thought that another revolution was necessary to correct the errors of the first. An attempt by the KGB to conclude an intelligence agreement with the new government failed.

Many national liberation movements had offices in Algiers, and Algeria provided weapons and military training for the struggle to liberate Africa. Among those who were inspired were Nelson Mandela and the African National Congress along with Yasir Arafat, and al Fatah received considerable support from the FLN.

Ben Bella was given a hero’s welcome in Havana during the Cuban missile crisis and echoed Castro’s judgement that Khrushchev had ‘no balls’; when he returned to Algiers, he berated the Soviet ambassador for the climb down. When a border conflict between Algeria and Morocco broke out in October 1963, Cuba came to Algeria’s aid, not the Soviet Union. It sent tanks and combat troops, but these were not needed. The tanks had been provided by the Soviet Union and were not to be used in Third World countries, but Castro had ignored this. As the US would not sell arms to Algeria, the Soviet Union stepped in and provided substantial quantities. Ben Bella was feted in Moscow, in May 1964, but he was overthrown a year later in a military coup.

Twenty-five countries gathered in Belgrade in 1961 to establish the Non-alignment Movement (NAM). National self-determination, mutual economic assistance and neutrality were the founding principles, and Algeria was the country to emulate. The meeting took place during the Berlin crisis, and the leaders of all states present sent identical letters to Khrushchev and Kennedy, warning about the potential for war and arguing for a peaceful outcome. The Third World saw itself as having arrived on the international stage.

The Sino-Indian Border War of October 1962 – provoked by the Indians establishing outposts on the Chinese side of the border which had been delineated under British rule whereas Beijing was protecting the outer limits of the Chinese Empire – and Indo-Pakistani War three years later (Moscow and Washington had to step in to broker a peace in both conflicts) badly dented India’s image. Bandung had underlined that disputes should be resolved through diplomatic channels. China’s aim was not to start a general war but to launch a decisive attack and then retreat so as to bring India to the negotiating table and even returned captured Indian heavy weaponry. During the June 1967 war between Israel and Egypt, Third World solidarity availed Nasser little, and he had to rely on Soviet arms to reequip his armed forces. The defeat was humiliating; the conflict was virtually decided during the first three hours when the Israelis destroyed 286 of 340 Egyptian combat aircraft on the ground, thereby leaving the ground forces without air cover during the battles in the Sinai desert. The KGB only discovered what was going on from Western news reports! This failure led the KGB to recruit academics and other specialists, among whom was Evgeny Primakov, and over 20,000 Soviet advisers were sent to Egypt.

The Organisation of African Unity (OAU) was set up in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, in 1963. Ben Bella was the main speaker.

The high hopes of the NAM and OAU were dashed by the harsh economic realities of the 1960s and 1970s. The Soviet model became more attractive as the American model and local efforts failed to generate the economic growth expected. The increasing economic and military might of the Soviet Union seemed to prove that the Soviet model was the one to choose for rapid economic advancement. Moscow had chosen to support nationalist movements in the 1960s, and gradually Marxism began to spread among Third World elites in the 1970s. Moscow could now engage ideologically with these new currents and the Cuban revolution added substance to the view that the future was bright – the future was communist. China sidelined itself during the mayhem of the Cultural Revolution (1966–76). The Soviet model was now the only game in town (Westad 2005: 97–109).

Why did the US intervene so often?

- It possessed the capability.

- Often intervention was viewed as defensive – to counter left or communist regimes; a major goal was to promote democracy but not if it helped communists to come to power; the US strongly opposed former colonial powers clinging on to their colonies – the exception was Malaya, where the UK was fighting a communist insurgency; Indochina was a struggle between colonialism and revolutionary nationalism; the armed struggle there gradually sucked in the US; it was the most effective way of exerting influence; the communist insurgency in the Philippines was crushed by 1953; China revealed the shortcomings of the American democratic model: Chiang Kaishek resisted efforts to promote democratic government and transparency; instead he prioritised the military struggle against the communists; when the Americans withdrew military support, the communists won.

- NSC-68 made the US responsible for imposing order throughout the world.

- Eisenhower, speaking in 1950, feared the US was in deep trouble in the Third World; even before the outbreak of the Korean War he confided: ‘I believe that Asia is lost with Japan, Philippines, the Netherlands East Indies (Indonesia) and even Australia under threat; India itself is not safe’(Chandler 1981: 1092).

- Vietnam was of key importance; opposition to French colonial rule gradually gave way to concerns about the rising influence of Ho Chi Minh, the North Vietnamese leader; Washington accepted the status quo and waited for non-communist nationalists to emerge (they never did); Eisenhower provided the French with $500 million annually in their conflict with the Viet Minh (League for the Independence of Vietnam);

- Vice President Richard Nixon, in December 1953:

If Indonesia falls, Thailand is put in an almost impossible situation; the same is true of Malaya and its rubber and tin; the same is true of Indochina; if Indochina goes under communist domination, the whole of south east Asia will be threatened, and that means the economic and military security of Japan will inevitably be endangered also.

(Chandler 1981: 58)

- This became known as the Domino Theory – ‘You have a row of dominos set up. You knock over the first one … What will happen to the last one is the certainty that it will go over very quickly,’ was how Eisenhower put it; it took root in American minds and led to intervention on a global scale; hence the US became responsible for protecting the world capitalist system; this led to it being willing to intervene politically, economically and militarily anywhere communism was perceived to be a threat; this involved backing dictators if they were threatened by a communist insurgency.

Iran was of special relevance to the West because of its oil; the British had very lucrative interests there, but sooner or later the Iranians would want to be master in their own house. In 1953, the government, headed by Mohammad Mossadeq, nationalised the oil industry. John Foster Dulles, secretary of state, warned President Eisenhower that this undermined the US position in the Middle East. Even more threatening, nationalisation might be a prelude to revolution and the Soviet Union would then secure these valuable assets and, if Iran went communist, other states in the Middle East would go red as well. The US ambassador regarded Mossadeq as not ‘quite sane’. When Sir Anthony Eden, Churchill’s foreign secretary, visited Eisenhower, he found him obsessed by the fear of a communist Iran.

Operation Ajax to remove Mossadeq was given the go ahead in June 1953 as a joint American-British undertaking. The young Shah, Mohammed Reza Pahlevi, did not want to be associated with this anti-constitutional démarche. Bribing local officials and helping to stage anti-Mossadeq demonstrations finally turned the tide, and the military went over to Colonel Fazlollah Zahedi, who had been hiding in the CIA mission, and Mossadeq was arrested. The coup was the first time the CIA had toppled a government abroad, and the belief grew that if it could do it in Iran, it could do it elsewhere on the planet. It did – in Guatemala – and even considered assassinating foreign heads of state who supported the ‘wrong’ side.

In 1957, the CIA and Mossad – the Israeli intelligence service – helped the Shah set up an intelligence and security service, SAVAK, which gained a reputation for brutality. In 1959, Iran and Israel signed a secret agreement on intelligence and military co-operation (Andrew and Mitrokhin 2005: 170). The KGB countered by forging documents which purported to show that Dulles denigrated the Shah and the US was plotting to overthrow regimes of which they disapproved. The Shah was taken in by all the forgeries.

On 8 December 1953, President Eisenhower delivered a speech at the UN General Assembly which was later dubbed his ‘Atoms for Peace’ speech. The president talked about nuclear energy being capable of providing abundant electrical energy to power the world. The US would provide the research reactors, fuel and scientific training to those nations which wished to establish a civilian nuclear programme. To ensure nuclear materials were not surreptitiously transferred to making weapons, what became the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) was set up under UN auspices. The ‘Atoms for Peace’ programme became a key factor in the Cold War as the superpowers offered to share nuclear expertise with their allies.

One of the first countries to take up the offer was Iran and, in 1957, a nuclear cooperation agreement was signed. In 1959 the Shah set up the Tehran Nuclear Research Centre at the University of Tehran, and in 1967 the US delivered a five-megawatt nuclear reactor together with the highly enriched uranium needed to fuel it. Iran signed the Nuclear Non-proliferation Treaty in 1968, becoming one of the first states to do so. Iranian students went to the US to be trained, and it took the country about a decade before it had a team of nuclear scientists capable of making full use of the research reactor.

In 1974, the Shah announced ambitious plans to build twenty-three nuclear power reactors during the next twenty years. In order to carry out this programme, the Shah requested that the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) accept and train young Iranian scientists and engineers. However, Washington suspected that the Shah’s real intention was to create a nuclear weapons programme and reduced the flow of sensitive technology. Uranium can be separated – spent fuel – and used for nuclear weapons; for this reason, the US opposed Iran’s plans to build a nuclear reprocessing facility. President Jimmy Carter prevented the Shah from getting the necessary technology and from obtaining it elsewhere. Eventually the Shah only signed one deal with a foreign company – West Germany’s Kraftwerk Union (a Siemens subsidiary) to build reactors at Bushehr. The Iranians formed a special group to collect the technology required to make a nuclear device (RFL/RL Iran Report, 9 July 2015). In 1979, the Shah was deposed, and Ayatollah Khomeini took over and acquired all the installations and expertise which had been built up. Since then, Iran has continued its efforts to build a nuclear bomb. So, unwittingly, Uncle Sam became the father of the present Iranian nuclear programme.

The US was not the only state which helped Iran develop its nuclear programme. China, between 1985 and 1997, was Iran’s principal nuclear partner. China provided four small teaching and research reactors, including one utilising heavy water, the key to producing plutonium and fissile material. China also provided Iran with uranium and chemicals to extract plutonium. Chinese engineers also worked with the Atomic Energy Agency of Iran, the official body responsible for implementing regulations and operating nuclear energy installations, to design a facility to be used to enrich uranium. It also helped to produce tubes and mining, and China may have helped with the centrifuge design supplied by Abdul Qadir Khan, the Pakistani scientist, who had a global black market proliferation network.

China joined the IAEA in 1984 and signed the Non-proliferation Treaty in 1993. China turned down an Iranian request for a team to observe a Chinese nuclear weapons test – an Iranian military source revealed this in 1996.

The US and China reached an agreement, in October 1997, according to which China was not to sell nuclear power plants, heavy water reactors and heavy water production plants and not to engage in any nuclear cooperation with Iran in the future. This resulted in it cancelling the delivery of two 300-megawatt power plants and a single twenty-seven-megawatt reactor.

In 2002, an Iranian opposition group revealed the existence of the Natanz enrichment facility, and Iran’s nuclear file was passed to the UN Security Council. China supported the latter’s resolutions sanctioning Iran in 2006, 2007, 2008 and 2010.

On 14 July 2015, the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action, agreed between the P5+1 group (US, UK, Russia, China, France and Germany) and Iran opened a new chapter in Iran’s nuclear relations with the rest of the world. The agreement foresees the lifting of sanctions (except those relations to human rights and terrorism). Assets worth about $100 billion will be unfrozen, and Iran’s aim is to increase its oil exports rapidly.

In 2014, Iran and Iraq each provided 9 per cent of China’s oil imports and thus were the Middle Kingdom’s fourth most important supplier. In the same year, Iran exported goods worth $24.3 billion to China, and foreign direct investment was $702 million in 2012. On the other hand, Saudi Arabia provides 16 per cent of China’s crude oil imports. China’s preferred option is stability in the Middle East and opposes regime change in Iran as Beijing perceives this to be Washington’s policy goal. The Middle Kingdom is at present involved in building six nuclear reactors in Pakistan and twenty-six worldwide (China Brief, Vol. 15, No. 14, 17 July 2015).

Growing Soviet influence in Syria led the US and Britain, in September 1957, to consider a plan to assassinate three top men in Damascus: Abd al Hamid Sarraj, head of Syrian military intelligence; Afif al Bizri, chief of the Syrian General Staff; and Khalid Bakdash, leader of the Syrian Communist Party. A joint CIA-MI6 operation envisaged frontier incidents and border clashes being staged to provide a pretext for Iraqi and Jordanian military intervention. Syria had to be seen to ‘appear as the sponsor of plots, sabotage and violence directed against neighbouring governments. The CIA and MI6 should use their capabilities in both the psychological and action fields to augment tension.’ Operations in Jordan, Iraq and Lebanon were to be blamed on Damascus. A Free Syria Committee was to be

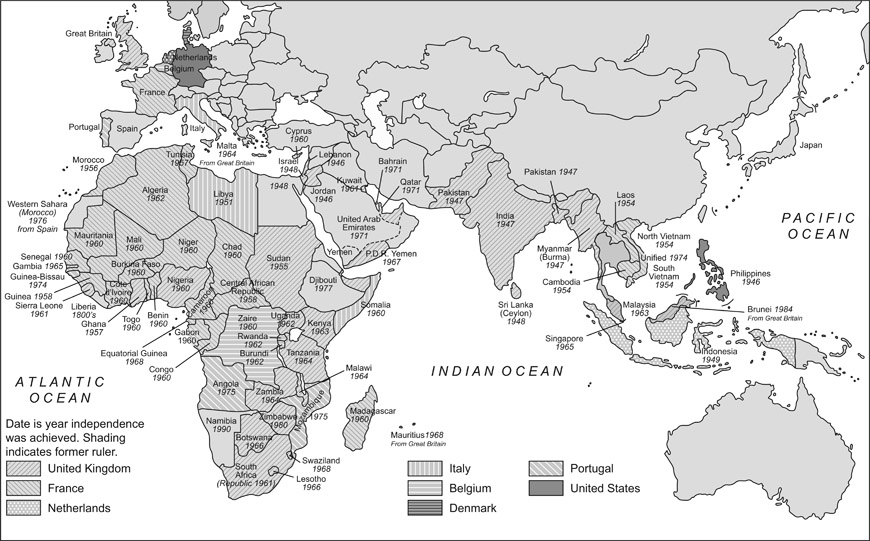

Map 4.2 The Soviet Union and the Middle East

set up and armed, and the CIA and MI6 would instigate internal uprisings – for instance by the Druze in the south – to help free political prisoners held in the Mezze prison and stir up the Muslim Brotherhood in Damascus. The Baath-communist government would be replaced by an anti-Soviet one, but this would be unpopular and repressive measures would need to be used.

Kermit Roosevelt, CIA director for the Middle East, was a major influence behind the plan and had first deployed his skills in Iran in 1953, when Mossadeq had been removed. Eisenhower and Macmillan backed the plan. It failed because Syria’s Arab neighbours refused to take action, and an attack from Turkey was deemed unacceptable (The Guardian, 27 September 2003).

In 1952, an Egyptian coup removed King Farouk, and the new leaders promised radical reform; Arab unity was another goal. Gamal Abdel Nasser, who had planned the overthrow of the monarchy, seized power in 1956, and his principal aim was to remove British influence. He had told Dulles in 1953 that the main enemy in the Middle East was British imperialism, not Soviet communism. He wanted the US to remain inactive as Arab nationalism overcame its domestic and external enemies. The main domestic enemy in Egypt was the Muslim Brotherhood. Nasser had played a leading role at Bandung; he forged a close association with Tito, and he was aware that he had to put together alliances if he were to succeed in the Middle East. The two immediate problems were taking control of the Suez Canal from the British and French and returning the Palestinian refugees to their lands and possessions. He nationalised the canal in July 1956 and began negotiations with Moscow for assistance and arms. In October, Israel attacked followed by British and French troops. President Eisenhower was furious and complained he had been double-crossed. After a week the British were within reach of their military objectives, but Washington forced a ceasefire and withdrawal of foreign forces. The British pound came under pressure and less oil was moved to Europe. Khrushchev assumed that the Americans supported the Suez adventure and that if military force could be used in Egypt it could also be deployed in Hungary. Khrushchev used the Suez crisis to threaten to intervene militarily and direct nuclear missiles at US bases in Britain. This was the first time the Soviet Union had engaged in brinkmanship and nuclear threats. Khrushchev incorrectly thought that this had forced the British and French to withdraw and concluded that nuclear threats were an effective diplomatic tool. This was put to a severe test during the Cuban Missile Crisis.

Nasser lost the war but won the peace; his standing in the Middle East rose and with it Soviet influence, as Britain and France ceased to be major players in the region.

The Eisenhower Doctrine was announced in January 1957. It promised regimes which were under threat from communism economic and military support. The president was concerned to stem the advance of pan-Arab nationalism in the Middle East and the loss of prestige there of the West in the aftermath of the Suez crisis. The nationalists could link up with communists and thereby strengthen the Soviet position in the oil-rich region. The first test came in 1958 when the US sent 14,000 soldiers and marines plus air force and naval support to support the Lebanese president; US forces stayed three months and then withdrew when the president’s term of office expired. In Iraq, the pro-Western king was assassinated, the new leaders entered into an alliance with the Iraqi Communist Party and Iraq began negotiations with Moscow for military aid. The British sent troops to Jordan to prop up the Hashemite monarchy there. Moscow warned local communists in the Middle East to be circumspect, and this turned out to be justified. In Iraq the Baath party – which declared itself to be socialist – eventually moved brutally against communists as did Nasser in Egypt. Increasing US support for Israel stoked Arab resentment as Washington began to work with Tel Aviv to counter Soviet influence in the region.

In South East Asia, the US kept 15,000 Chinese (Guomindang) troops in Burma (Myanmar) for possible use against the People’s Republic and to exert pressure on the left wing government in Rangoon (now Yangon). In Cambodia, Washington supported rebellions against Prince Sihanouk because of his cooperation with the left and the People’s Republic of China, and the Americans also paid for the armies in Laos and South Vietnam which were to counter the rise of the Viet Minh and the Left.

However, it was in Indonesia, the most populous Muslim state in the world, that the US concentrated greatest efforts to change the direction of the regime. Sukarno wanted more rapid economic growth, and a parliamentary system gave too much influence to existing elites. In 1957, he requested a loan from the US but was turned down, so Khrushchev stepped in and provided $100 million for military hardware. Sukarno then declared that there would be guided democracy overseen by four parties, one of which was the Indonesian Communist Party (PKI). The Americans decided to support separatist movements, especially in Sumatra and Sulawesi. Weapons were delivered, and US, Guomindang and Filipino pilots flew combat missions from Sumatra bases, and Dulles thought it might be possible to land US troops there. The aim was to break up Indonesia, but Sukarno was able to mobilise military and political support and survive. The capture of a US pilot, shot down on a bombing mission, proved that the US was involved and inflamed Indonesian opinion. The rebels fragmented, but the US continued to support them in northern Sumatra.

Hence during the Eisenhower era, Washington developed a strategy which involved intervening in countries regarded as going left wing. This was viewed as a halfway house towards communism. The obverse of this was that Third World countries became more resistant to the American model.

Africa was a problem for Washington in the 1950s and 1960s. As dedicated anti-colonialists, they opposed British, French, Belgian and Portuguese rule there. But were these tribal societies ready for self-rule? Would civil war and chaos follow a precipitate withdrawal of the Europeans? Africans could be quickly seduced by Marxism and lead to the rapid expansion of Soviet influence there. In the US, African-Americans lived in a segregated society deprived of many human rights. The natural ally of the US was South Africa. After winning a whites-only election in 1948, the Afrikaners replaced English with Afrikaans (the word means ‘African’ in Afrikaans) as the first national language. They also imposed strict segregation (apartheid) in a country in which 80 per cent of the population was black. The Eisenhower administration developed a good relationship with Pretoria. The police killing of Africans at Sharpeville in 1960 changed the relationship at a time when the civil rights movement was under way in the US.

The Kennedy administration viewed Africans as adolescents but dropped the idea that socialism did not fit the ‘African tribal mentality’, so America had to intervene in black Africa and not leave the continent open to Soviet influence. The CIA began backing Holden Roberto’s Frente Nacional de Libertação de Angola (FNLA) (National Front for the Liberation of Angola) and Eduardo Mondlane’s Frente de Libertação de Moçambique (FRELIMO) (Front for the Liberation of Mozambique).

The Belgian Congo (Belgium had acquired the mineral-rich colony in 1908) was home to over 200 tribes. Brussels concentrated on exploiting the riches and paid little attention to the locals. It became independent of Belgium on 30 June 1960, and Patrice Lumumba, head of the Movement National Congolais (MNC) (Congolese National Movement), was elected prime minister. He was a dapper dresser and had a taste for women, beer and the Congolese equivalent of marijuana. The US had acquired Congolese uranium to develop their nuclear arsenal and, although no longer dependent on the Congo, Washington set out to ensure the Soviet Union did not gain access to the uranium. In May 1960, the head of the CIA, informed President Eisenhower that Lumumba was being supported by the Belgian communists. There were no institutions in the country; it began to break up, and Lumumba was faced with a military mutiny. The mineral-rich Katanga province seceded, partly in response to Belgian prompting. Lumumba asked the UN to intervene and expel the Belgian military. The request was turned down, and Lumumba retorted that he was turning to Moscow for help, but this was akin to dancing with the devil. This enraged the Americans who rated Lumumba worse than Castro. Lumumba went to Washington and made a determined defence of his country’s sovereignty and the right to choose its allies. Eventually it was decided the best option was to assassinate Lumumba and replace him with a military general, Joseph Mobutu – a ‘completely honest and dedicated man’ – in the opinion of the US ambassador.

It is still uncertain who ordered the liquidation of Lumumba: the CIA or Mobutu. The assassins were not CIA agents, but it supplied the weapons they used. (The same modus operandi was deployed to assassinate Generalissimo Rafael Trujillo, leader of the Dominican Republic, in May 1961.) Lumumba was captured by Congolese soldiers in December 1960; he was handed over to his archenemies, the Katangans, who tortured him for five hours and then took him into the jungle and shot him in January 1961. His body was buried in a shallow grave with one arm protruding. He was disinterred, dismembered and the body parts dissolved in battery acid. The Belgian responsible for this pulled out two of his teeth as souvenirs. They were capped with gold (Gerard and Kuklick 2015: 194).

The ramshackle Mobutu regime managed to get rid of the Soviet, Eastern European and Chinese advisers who had clustered around Lumumba. When Mobutu visited Washington in 1963, Kennedy told him that he had saved the Congo from communism, but the brazen military intervention and the removal of a hero to many Africans were bound to stir up anti-American and anti-Western emotions throughout the continent. Che Guevara, unknown to the Americans, had headed a Cuban group to assist Lumumba and remarked later that he had learnt a lot about the weaknesses of counter-insurgency strategies there. An unresolved mystery concerns the death, in a plane crash in September 1960, of UN Secretary-General Dag Hammarskjöld, who was on his way to negotiate a ceasefire between UN and Katangan forces. Some speculated that the plane crash was not an accident and that it had been shot down.

Under Mobutu, who became the richest and most corrupt man in Africa, the country was renamed Zaire in 1971, and in 1997 it became the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

The Monroe Doctrine (1823) claimed Latin America as the US’ zone of influence, and European powers were to stay out of the region. The great inequality of wealth fostered the development of communist parties, and Washington began to be concerned lest Moscow order local communists to hold up the export of strategic raw materials.

Stalin dismissed Latin American states as the ‘obedient army of the US’, and until the late 1950s, the Soviets only maintained three embassies in the sub-continent: in Mexico City, Buenos Aires and Montevideo. Small subsides were disbursed to local Communist Parties but nothing like the money and resources extended to parties in the West and Asia.

The first time that the US intervened directly was in 1954 in Guatemala. The president, Jacobo Arbenz, legalised the Communist Party, and it began to acquire influence. He made land reform (91 per cent of arable land was owned by large landowners) the centrepiece of his programme of social justice. The CIA began to arm and train Guatemalan opposition groups in Honduras. President Eisenhower gave the go-ahead for US aircraft to attack Guatemalan military bases. The military changed sides and removed Arbenz. Most communists escaped abroad, including Che Guevara, who was there to study developments. Dulles thought that dictators were the best leaders to work with in ‘adolescent’ Latin American states.

It was Castro who awakened Soviet interest in the subcontinent which was, and is, traditionally anti-American and anti-capitalist. The lead in expanding contacts with Latin America was taken by the KGB rather than the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, and this remained the pattern while Andrei Gromyko was foreign minister. Mikhail Suslov, number two in the party and therefore the chief ideologue, shared the KGB’s enthusiasm for the Third World. Boris Ponomarev, head of the international department in the Party Secretariat, dealt with the leaders of the national liberation movements in the Third World. He was very conservative, and Khrushchev thought he was as ‘orthodox as a Catholic priest’. Gromyko despised Ponomarev who returned the favour. The KGB, Suslov and Ponomarev viewed the great contest between the Soviet Union and the US, that between capitalism and socialism, as being won by whomever was victorious in the Third World.

A boost to these views was the declaration, in the new party programme adopted in 1961, that the ‘liberation struggles of oppressed peoples is [sic] one of the mainstream tendencies of social progress’. A grand plan to use national liberation movements and the forces of anti-imperialism as a pincer movement to envelop the US was conceived, headed by the KGB.

In Brazil, in 1964, President João Goulart caused concern because of his radical economic and social agenda, and as he had also recognised Cuba and other communist countries, he had to go. President Lyndon Johnson saw him as a dangerous radical who should be removed by any means possible. The US banked on the military removing him, and it eventually did – sweetened, of course, by American largesse. The new president, Castelo Branco, did not follow the political and economic advice of a legion of American advisers. He was more concerned with dealing with his political enemies, and Brazil remained a military dictatorship until 1985. The Brazilian military became a close strategic ally of the US, and in 1965 Brazil helped Washington to invade the Dominican Republic. In 1966, Uruguay was warned that if the wrong person was elected, the country would face a Brazilian invasion (Westad 2005: 111–52).

The US made some accidental gains without any direct involvement. Military coups in the mid-1960s in the Congo, Indonesia, Algeria and Ghana took these countries out of the Soviet orbit. A key factor was the inability of the Soviets and Chinese to intervene militarily. They could in Vietnam, for instance, because it had a common border with China.