The heading in 1:1 (The proverbs of Solomon, son of David, king of Israel) does not necessarily mean that the entire book is written by Solomon. The precise way in which they are proverbs of Solomon is not made clear, so it could imply either that he wrote them or collected them. It may be only a dedication, saying that this collection is in memory of Solomon, since it could also be translated ‘proverbs for Solomon’. However, the association of Solomon with proverbial sayings supports the option of Solomonic authorship. We know from 1 Kings 4:29–34 that he ‘spoke 3,000 proverbs’ (more than in this book), which implies that he was more than capable of writing the proverbs found in this book.

However, this heading may refer only to chapters 1 – 9, since other headings are also found in 10:1 (also The proverbs of Solomon), 22:17 (the words of the wise) and 24:23 (the sayings of the wise). The last two non-Solomonic headings suggest that these parts were either incorporated by Solomon or added to his collection at a later date. In 25:1 there is explicit mention of the men of Hezekiah (late eighth–early seventh centuries bc) who copied or edited some further proverbs of Solomon. Finally, chapters 30 – 31 have separate authorship titles (The words of Agur, The words of King Lemuel), which preclude him from being the author of the entire book. So as a book it claims to be substantially, but not entirely, Solomonic.

Some evangelical authors dispute the Solomonic authorship of chapters 1 – 9 (e.g. Lucas 2015: 6, ‘probably another anonymous, non-Solomonic, collection’), and it certainly cannot be finally established. But what has drawn scholars into disputing a Solomonic connection with chapters 1 – 9 has been the longer wisdom instructions found there, unlike the sentence sayings of chapter 10 onwards. However, Waltke (2004: 31–36) builds an argument for Solomonic authorship based on considerable evidence cited by Kitchen and Kayatz from parallel ANE (mainly Egyptian) wisdom sources. These attest to similar long instructional material well before the time of Solomon, so there would be nothing anachronistic about him writing these longer instructions as well as the shorter proverbs. Steinmann (2009: 1–19) has also argued robustly for the consistency of thought and vocabulary between chapters 1 – 9 and 10 – 24, supporting Solomon’s authorship of both parts.

In the end, authorship is not a major focus in scholarship on the book; it is acknowledged by all that proverbs usually have a long oral prehistory before they are written down. What we have in proverbial literature is ‘the wisdom of many, and the wit of one’.1 It takes a whole community to formulate and validate a proverb, even if only one person finally captures that wisdom in a pithy and memorable set of words. God has seen fit to include in Scripture these literary genres that express God-given insights developed over many years. Indeed, Agur and Lemuel (the authors of 30:1 – 31:9) were probably not Israelites, and some of chapters 22 – 23 appear to be based on (but adapted from) an Egyptian wisdom text, the Instructions of Amenemope. Certainly, Solomon has put his significant stamp on the shape and structure of at least chapters 1 – 22, but it is highly unlikely that these chapters were written from scratch by Solomon.2

All this makes the question of the date of Proverbs a little problematic. Much of it would have circulated in oral form before Solomon collected, edited and crystallized the contents. Solomon’s theological structuring of the first twenty-two or twenty-four chapters would have taken place in the tenth century bc, while chapters 25 – 29 were compiled by the men of Hezekiah’s time (late eighth–early seventh centuries bc). It appears that materials from Agur (ch. 30) and Lemuel (31:1–9), as well as the closing poem (31:10–31), were added after this time, but our lack of information about the identities of these authors make it very difficult to date. Even Waltke (2004: 36–37) and Steinmann (2009: 17–19) suggest that this final editing could have taken place as late as the post-exilic Persian period (fifth–fourth centuries bc). Proverbs is thus a book that had its core established in the time of Solomon, but its final form took shape some centuries later.

The wisdom literature of Israel, which includes Proverbs, shares much in common with a broader interest in wisdom, scribes and instruction in the ANE. The strongest links with Proverbs occur in Egypt, where there are clear parallels between the longer instructions or lectures of Proverbs 1 – 9 and a wide variety of Egyptian texts. The Egyptian instructions are first found well before Solomon (e.g. Hardjedef, Kagemni, Ptahhotep, Merikare) and continue for many centuries thereafter. While it is beyond the aims of this commentary series to explore these in any depth, this has been done elsewhere in an accessible way.3 The individual sentence sayings are less common in Egyptian wisdom, but were present in Mesopotamian wisdom at a very early stage in the Sumerian proverbs (see Alster 2005). However, even in the Egyptian texts the basic pattern of a teacher (called ‘father’) handing down instruction to his ‘son’ is reflected throughout Proverbs. There is ongoing dispute over whether the court setting of wisdom in Egypt was reflected in Israel, but at least some of Proverbs seems to reflect a similar setting (see Dell 2006: 67–79). There is fairly general agreement that at least part of 22:17 – 24:22 is a filtered adaptation of the earlier Egyptian Instructions of Amenemope (but see the cautions of Kitchen 2008: 562–563 and the discussion of Lucas 2015: 32–38). Other parallels between Proverbs and Egyptian wisdom include thematic links like those between retribution and the Egyptian concept of Ma’at (‘truth/order’), a prominent focus on speech, and similar lists of virtues and vices.

The nature of a proverb needs to be understood in light of the various literary forms actually used in the book. There is such a variety, including sentence sayings (what we normally understand as a proverb, especially in chapters 10 – 22), longer didactic discourses (common in chapters 1 – 9), numerical sayings (e.g. 6:16–19; 30:21–31), ‘better than’ sayings (e.g. 12:9; 15:16–17) and even an acrostic poem (31:10–31). Both the word māšāl, ‘proverb’, and the book itself can refer to this wide range of wisdom forms (see the next section).

A proverb makes an observation that must be confirmed by those who hear or read it. As a comment about how things are, it usually lacks an imperative. It is a generalization based on experience, or a distillation of knowledge gained by experience – it is not a revealed truth (although God may be behind the discernment process), or a law or a promise.

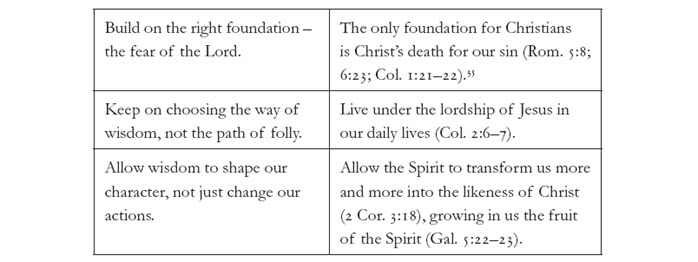

Chapter 26 warns us that a proverb is not automatically effective, as it can be misused. Thus a proverb in the mouth of a fool can be as useless as a lame man’s legs (26:7) or as dangerous as a thorny branch in the hand of a drunk (26:9). The key here is the phrase in the mouth of fools. Within chapters 1 – 9, fools are those who reject the starting point of the fear of the Lord (1:7), who keep on choosing the path of folly not the way of wisdom (9:1–6, 13–18), and who refuse to allow their character to be shaped by wisdom (2:1–11). In other words, a proverb is not fully useful unless its hearer or reader has made the fundamental and ongoing choices called for in chapters 1 – 9.

One way to misuse a proverb is to assume that it applies all the time. While the Mosaic law or a prophetic word must always be obeyed, wisdom is needed to know when to use which proverb. In Proverbs this is seen most clearly in the so-called ‘contradictory proverbs’ in 26:4, 5:

Answer not a fool according to his folly,

lest you be like him yourself.

Answer a fool according to his folly,

lest he be wise in his own eyes.

We cannot ‘obey’ verse 4 and verse 5 at the same time; we need to work out which truth is best for the situation we face.4 This ‘sometimes applicable and sometimes not applicable’ aspect can be seen in contemporary English proverbs as well:5

‘Many hands make light work’ vs ‘Too many cooks spoil the broth’

‘He who hesitates is lost’ vs ‘Look before you leap’

‘Out of sight, out of mind’ vs ‘Absence makes the heart grow fonder’

Proverbs are presented in an absolute, unqualified form, and we need to discern when to apply one and not another. Some promises (e.g. God will forgive the sins of those who trust in Jesus) are always true and apply to all circumstances. A proverb, on the other hand, is not intended to cover every situation and often needs to be fleshed out by other perspectives.6 A proverb is, however, still true, even if it does not always apply. This will mean that it is useful to balance the varying perspectives of different proverbs on the same theme (e.g. money, speech, work). Thus, we need to read the observations of the poor having few friends (14:20) together with an encouragement to be generous to the poor (14:21). In the wider canon the books of Job and Ecclesiastes give us a nuancing of the teaching of Proverbs, especially on the idea of retribution (i.e. that God rewards the righteous and punishes the wicked). This nuancing is present even within the book of Proverbs itself, for in 24:16 the writer insists that the righteous will rise and the wicked will be brought down, but that the righteous person may fall down seven times. Similarly, someone’s wealth can be taken by wrongdoers without any hint that the person deserved it (13:23).

Indeed, sometimes Proverbs observes an aspect of society without either commending or criticizing (e.g. 25:20; 20:14), although at other times the lesson is clearly implied even though not stated (e.g. 11:22). Yet Proverbs is content at times simply to describe how life is, such as the difficulty of making friends when you are poor (14:20; 19:4, 7), or the effectiveness of a bribe (18:16; 21:14). They are making sense of the world by observing what works in life and what does not.

It is also vital to understand that proverbs do not operate as guarantees. Many parents rightly value 22:6:

Train up a child in the way he should go;

even when he is old he will not depart from it.

Yet, this is not a promise to ‘claim’, but an observation that this sequence typically happens. It should not be pressed so hard as to deny that the child has any responsibility for his or her actions. It needs to be qualified by seeing that the child also has a role to play. The proverb helps us to see that parental training has a strong impact, not that it bears sole responsibility. So the proverbs impart godly wisdom to us when they are rightly understood as proverbs, not promises.

Proverbs also observes that living wisely often lengthens the years of your life (3:1–2; 9:10–11). Yet this is not meant as a ‘guarantee’ of long life for the godly (remember that Jesus died young), but is based on observations that godly persons use good sense and do not indulge in riotous living. Their lifestyle will promote health in body and mind. Thus, generally speaking, they live longer. Similarly, 3:9 urges us,

Honour the Lord with your wealth

and with the first fruits of all your produce;

then your barns will be filled with plenty,

and your vats will be bursting with wine.

While we know there are exceptions, it is true that careless living will often lead to poverty (21:17). Yet Proverbs recognizes that some will be poor because they were cheated by the wicked (13:23), so that you cannot diagnose a person’s spiritual condition from their wealth. This was the mistake of Job’s friends.

The book of Proverbs is written according to the conventions of Hebrew poetry. Even the didactic narrative in 7:6–27 is a narrative poem. The basic individual proverb is bilinear, that is, a two-line saying usually found in one verse. Hebrew poetry does not rhyme, but there is a kind of ‘thought-rhyme’ (and sometimes other features like alliteration or assonance) in which the second line echoes the first, but in a variety of ways. This is technically called parallelism.

Many proverbs have been regarded as using one of three main types of parallelism, and this remains a helpful place to start.7 In synonymous parallelism, the second line is conveying a similar idea to the first, with only a slight variation. Proverbs 18:15 is a good example:

An intelligent heart acquires knowledge,

and the ear of the wise seeks knowledge.

Antithetical parallelism occurs where the second line contrasts with the first. Proverbs 13:3 observes,

Whoever guards his mouth preserves his life;

he who opens wide his lips comes to ruin.

Most of chapters 10 – 15 are of this sort, and it is often expressed in the English versions by the conjunction ‘but’, as in 13:6:

Righteousness guards him whose way is blameless,

but sin overthrows the wicked.

Step (or synthetic) parallelism is found when the second line is neither expressing the same idea, nor a contrasting truth, but rather developing the idea of the first line into a fuller one by taking it one step further. So in 19:14:

House and wealth are inherited from fathers,

but a prudent wife is from the Lord.

The ‘better than’ sayings have a distinctive form, and are used to make a striking comparison (a form of antithetical parallelism), as in 17:1:

Better is a dry morsel with quiet

than a house full of feasting with strife.

Some proverbs are simple comparisons (possibly a type of synonymous parallelism), often using the word ‘like’, as in 26:23:

Like the glaze covering an earthen vessel

are fervent lips with an evil heart.

The numerical sayings are an elaborate form of comparison, often commenced by successive numbers (x; x + 1), as in 6:16 or 30:18:8

There are six things that the Lord hates,

seven that are an abomination to him.

(6:16)

Three things are too wonderful for me;

four I do not understand.

(30:18)

The alphabetic acrostic form is also found in the final poem of 31:10–31. Here each of the twenty-two verses begins with a different letter of the Hebrew alphabet and occurs in alphabetical order.

While the discussion of parallelism can become very technical and esoteric, most readers will find that identifying the kind of parallelism used in a proverb will help them to read it with more understanding.

Proverbs paints a picture of the good life – or better, the good community – in its daily patterns and activities. The focus on the present can be seen in its teaching about God. In terms of God’s actions in the past, they only concern the creation of the world (e.g. 3:19–20; 8:22–31) and nothing since. Most of the explicit statements about God in Proverbs speak to the present and the future – what the Lord is doing and can be expected to do: for example, he weighs the spirit (16:2), tries hearts (17:3) and searches the innermost parts (20:27). God is expected to dole out material rewards and punishments to people during their lifetime (e.g. 3:9–10; 22:4). There is no emphasis on end-time judgment, and the great majority of statements concerning consequences of behaviour does not mention God by name. In 13:21a, for example, it is not that God will punish wrongdoers, but simply that disaster pursues sinners. This is not to shut God out of causing the consequences, but rather to concentrate on the here-and-now effects of what we do in our everyday lives.

Goldsworthy points out that Proverbs is fundamentally an optimistic book, teaching that wisdom and life are within our grasp. They are so because they are God’s gift, and the human task. He suggests that ‘Proverbs defines goodness in terms that are wider than morality and ethics. It is the order that underlies the creation’ (1987: 85). Proverbs does not speak of the fall of humanity into sin, although it may be presupposed from earlier OT books. What Proverbs affirms is that any chaos brought by sin has not conquered, and that the order in creation can still be perceived. Wisdom is about living life to the full, and Proverbs calls us to a decision to stand with either the wise person or the fool.

Proverbs assumes that people are free to choose their course of action in life and are being urged to choose the way of wisdom. While a moral code undergirds the book of Proverbs, its real intent is to train a person, to actively form character, to show what life is really like and how best to cope with and manage it. Yet its flavour is so different from the stern prohibitions of the law and the strong rebukes of the prophets. Murphy (2002: 15) says, ‘It does not command so much as it seeks to persuade, to tease the reader into a way of life.’ The urging of Proverbs is not based on appeals to God’s saving acts, nor Israel’s history, nor even the distinctives of Israel as God’s chosen people. While it is addressed to Israelites, it has in view the followers of God as human beings seeking to make sense of life before the one who has created and sustains them.

While there are clear warnings about the way of folly, the book as a whole focuses more on the patterns that will lead to living well in God’s creation. This emphasis on the regularities and normal activities of daily life is a significant part of the book’s appeal to contemporary readers. While some of the OT seems foreign in its concerns, the issues explored in Proverbs are familiar and topical. McKenzie (1996: xi–xiv) has described us as living in ‘a proverb-filled world’. She imagines what our life would look like if it were shaped by the book of Proverbs, proposing what might be written on our tombstone (McKenzie 2002: 108):

I lived with a listening heart, attentive to God’s wisdom all around and within me. With my attention on Divine Wisdom, I was able largely to close my ears to the influence of foolish people and my own unruly appetites. I was faithful to my spouse and controlled my appetites for food and drink. I was industrious, controlled my temper and curbed my unruly tongue. While I came to realize that life contains a measure of mystery and that God is ultimately in charge of things, I focused on those areas of life where, by making wise choices, I could usually ensure auspicious outcomes. I ordered my life so that I knew a measure of peace of mind and worked for harmony in my community. While I respected the poor as those whom God created and loves, I worked to ensure that I would not share their lot. As a result, I secured a reputation for integrity and prudence among my peers.

That is the flavour of the book of Proverbs.

Some aspects of the structure of the book are very clear, but others are quite controversial and disputed. There is general agreement that chapters 1 – 9 are distinct from the following chapters as they contain longer, more cohesive instructions or lectures rather than the shorter sentence sayings of chapters 10 – 29. The final two chapters (30 and 31) round off the book with two further collections and a poem on wisdom exemplified as a woman.

Proverbs 1 – 9 contains long, cohesive units of thought, unlike the sentence sayings of the rest of the book. A number of scholars have identified ten major units of thought in Proverbs 1 – 9. Whybray (1994: 25) labelled them as ‘instructions’ (on analogy with Egyptian texts), but McKane (1970: 9) argues that, unlike the Egyptian texts, they are not instructions for court officials, but for young men in the broader community, with the aim of promoting a particular way of life.

Fox (2000: 45) calls them lectures (i.e. a father lecturing his son or sons on moral behaviour), comprising three parts:

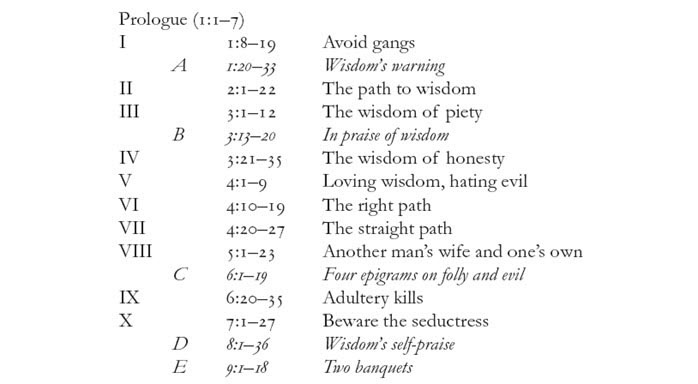

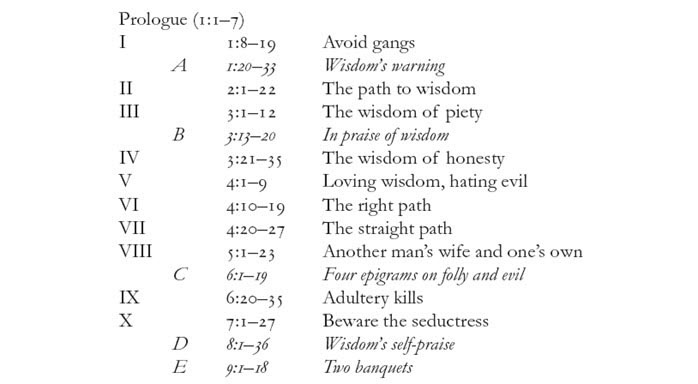

Fox (2000: 44–45) suggests that these ten lectures (I–X) are interlaced with five interludes (A–E), which are largely reflections on wisdom. He sets out the components as follows:

While there may need to be further discussion about the titles given to each section, the essential outline of these chapters seems well described by his proposal.

The remainder of the book (chapters 10 – 31) can be broadly structured by the headings found there. The first major section (10:1 – 22:16) is introduced by the title The proverbs of Solomon. This section is comprised of one- or two-line sentence sayings, which are not neatly arranged in terms of content. Every now and then there are small clusters of proverbs around a single theme, such as the use of words in 10:18–21 or the mention of kings in 16:12–15, but these are clear exceptions to the dominant, seemingly random pattern.9

There is, however, a growing desire among some scholars to read the book of Proverbs as a meaningful book, not just a waste-paper bin of gathered wisdom. Bartholomew (2001: 6–7) notes that just as in Psalms or Isaiah, attention is being paid to the shape of the book as we have it in its canonical form, with evidence of editing, gathered collections and interconnections. While clearly not every proverb is linked to the one it follows or precedes, many more are linked than was once thought, as Van Leeuwen (1988) has demonstrated in relation to chapters 25 – 27. Hildebrandt (1988: 209–218) has also drawn attention to a number of proverbial pairs (10:15–16; 13:21–22; 15:1–2, 8–9; 26:4–5), giving hints of a more cohesive structure in chapters 10 – 29. Bartholomew’s suggestion is that we should read the book of Proverbs like other books, starting at the beginning and allowing the meaning to accrue as we move along. While this is easily done in relation to chapters 1 – 9, we should ask if it is more possible in chapters 10 – 31.

A key proponent of this new trend is Knut Heim’s Like Grapes of Gold Set in Silver (2001).10 He noted that seven out of nine commentaries he surveyed acknowledged that there is some structure in this section that should affect how it is interpreted (even if there is no agreement about the details). The kind of features he points to include the following (Heim 2001: 63): ‘chapter divisions, “educational” sayings, paronomasia (the use of a word in different senses or the use of words similar in sound to achieve a specific effect, as humour or a dual meaning; commonly a pun of some form) and catchwords, theological reinterpretations, proverbial pairs, and variant repetitions’. While Heim concludes that none of these is sufficient on their own, the combination of phonological, semantic, syntactic and thematic repetition factors mounts a powerful case for a deliberate attempt to structure this section into clusters of between two and thirteen verses. In developing the analogy found in 25:11, he says, ‘The cluster forms an organic whole linked by means of small “twiglets”, yet each grape can be consumed individually. Although the grapes contain juice from the same vine, each tastes slightly different. It doesn’t matter in which sequence the grapes are consumed, but eating them together undoubtedly enhances the flavour and enriches the culinary experience.’11

Longman (2006: 38–42) has criticized Heim’s approach, saying that the criteria are so broad and varied that different scholars will come up with different clusters. These clusters can therefore be just as much a projection of the commentators as a reality that emerges from the text. Longman concludes that the sentence sayings are, in the end, arranged in a more or less random fashion, especially when it comes to their content. Each proverb is on its own for meaning.

More recently, Fox has produced his commentary on chapters 10 – 31, and has pointed out that this programme of trying to find clusters goes back to medieval Jewish commentators (twelfth century), or perhaps even earlier. He observed that Heim relied on linking devices rather than clear boundary markers. His conclusion is that the process that best explains the grouping we can find in this part of the book is that of associative thinking, that is, a word or sound or root or phrase triggers off for the compiler another proverb which is then included. He gives an example of how this process works in 19:11–14. Here patience in verse 11 triggers the thought of wrath, the opposite of patience (v. 12); which is an irritation, leading to the thought of an irritable wife (v. 13); which provokes the thought of a virtuous one (v. 14).12 Fox suggests that there is no reason to look for or assume the existence of any larger patterns, as there are other forms of literary artistry which also give unity. His image is not one of clusters of grapes, but of each proverb being like a jewel, with the book like a heap of different kinds of jewels. They do not need to be sorted into neat rows or separate piles in order to be attractive.

While Waltke (2004; 2005) has identified a number of units and subunits, this has been taken further by Lucas (2015: 15–22; see also 2016: 37–42). Lucas divides much of this Solomonic collection into ‘proverbial clusters’, but has tried to base this more on thematic connections. In this commentary I also have tried to develop some connections and groupings, largely on the basis of thematic or content links. In this matter, to quote a proverb, the proof of the pudding is in the eating. While the exact boundaries differ in these various scholarly attempts to identify groups of proverbs, the many connections identified do suggest that these proverbs have come together over a period of time rather than in a single and simple work of editing. Longman’s conclusion is to go back to the idea of interpreting the proverbs as randomly structured; mine is to assume that first the proverb is to be read on its own, but there is always a need to see if it might connect to surrounding proverbs.

There are a number of other indicators of some structuring happening in this section. Many commentators have pointed out the preponderance of antithetical parallelism in chapters 10 – 15 (on one count, 163 out of 183 proverbs), while chapters 16 – 22 are more characterized by either synthetic or synonymous parallelism. Bartholomew (2001: 11–13) has suggested that character-consequence link is very strong in chapters 10 – 15, with a stress on the contrast between the lifestyles of the righteous and the wicked. He then observes that most of the exceptions to this pattern of retribution (God rewarding the righteous and punishing the wicked) are found in chapters 16 – 22. Van Leeuwen (2005: 638) has concluded that ‘Prov. 10–15 teaches the elementary pattern of acts and consequences, while chs. 16–29 develop the exceptions to the rules.’

There are other patterns as well. With the exception of two instances in the linking passage (14:28, 35), the king is not mentioned in chapters 10 – 15, but there are many references in chapters 16 – 22 (16:10, 12, 13, 14, 15; 17:7; 19:12; 20:2, 8, 26, 28; 21:1). Chapters 16 – 22 also contain more ‘better . . . than’ sayings (12:9; 15:16–17; 16:8, 16, 19, 32; 17:1; 19:1, 22; 21:9, 19; 22:1; see also 25:7, 24; 27:5, 10; 28:6) than the rest of the book. This provides a form of prioritization as one thing is judged better than another.

These differences suggest that there is some structure in chapters 10 – 22 after all. Of particular significance here is Whybray’s observation of a high concentration of ‘Yahweh sayings’ at the seam of the two sections (chapters 10 – 15 and 16 – 22) in 15:33 – 16:9. In 10:1 – 22:16 one third of all the sayings containing the Lord are found in chapters 15 and 16, with nine out of ten verses in 15:33 – 16:9 using the Lord, making it the largest group of sayings with thematic unity (Whybray 1990; see also Dell 2006: 106 for some minor recounting). This not only gives a theological flavour to the final form of the whole Solomonic section, but also provides structure and cohesion. On balance, then, there are enough indicators of a variety of structuring devices to suggest that the proverbs of 10:1 – 22:16 are not simply randomly arranged.

Structure is less problematic in the rest of the book. Further titles are found in 22:17 (the words of the wise, covering 22:17 – 24:22) and in 24:23 (These also are sayings of the wise, covering 24:23–34). These titles introduce collections of sentence sayings. The words of the wise can be grouped into an introduction in 22:17–21 and three sections (22:22 – 23:11; 23:12–35; 24:1–22). The ‘further sayings’ are only a small section of twelve verses that are best seen as having three parts (24:23–25, 26–29 and 30–34).

They are followed by chapters 25 – 29, given the title in 25:1: These also are proverbs of Solomon which the men of Hezekiah king of Judah copied. Many have concluded that there are two collections here, as chapters 25 – 27 contain many striking metaphors and comparisons, and little antithetic parallelism, while these features are reversed in chapters 28 – 29. Van Leeuwen (1988) has done a careful analysis of chapters 25 – 27 and identified a coherent structure there, made up of six parts (25:2–27 [1–28]; 26:1–12, 13–16, 17–28; 27:1–22, 23–27). Chapters 28 – 29 can be divided into four sections (28:1–12, 13–28; 29:1–15, 16–27; so Finkbeiner 1995: 3–4).

The book finishes with the sayings of Agur (ch. 30) and Lemuel (31:1–9). Chapter 30 is a collection of wisdom proverbs, using mainly numerical sayings.13 The oracle to Lemuel is a short section of nine verses, with three parts (31:1–3, 4–7, 8–9). Finally comes a description of the perfect wife in 31:10–31, which is quite a distinct section, but possesses no title. In the opening chapters wisdom is personified as a woman, and this acrostic poem shows an example of wisdom lived out in practice. The idea of the fear of the Lord makes an important structural contribution to the book, as it brackets chapters 1 – 9 (1:7; 9:10), is found in the ‘theological kernel’ (15:33; 16:6) and here finally at the close of the book. This is a coherent unit with an introduction (31:10–12), an outline of her activities (31:13–27) and a description of those who praise her (31:28–31).

Looking for theology in Proverbs may seem to be an ambitious task. Back in 1986 Roland Murphy (1986: 87–88) wrote, ‘The Book of Proverbs would seem to be a very modest candidate for theological exegesis.’ Yet, while he concedes that the theology of Proverbs is different from the focus of ‘modern theology’, he insists that its concern with understanding people in terms of their relationship with God is deeply theological.

A number of scholars have taken the view that the book of Proverbs – and especially the sentence sayings of chapters 10 – 29 – are simply examples of ‘secular’, non-theological wisdom. Yet Alan Jenks (1985: 87–88) has argued that instead of wisdom becoming more ‘theological’, it was originally theological. Three basic theological presuppositions or principles undergird even what is usually understood to be the oldest section of Proverbs (chapters 10 – 29):

Norman Whybray (1990: 153–165) examined the ‘Yahweh-sayings’ in the book to explore what they taught about God. He finds a clear insistence that God is the Creator. Thus, 3:19–20 shows that he is the Creator of heaven and earth; also 8:22–31 Creator of earth, mountains, sky and sea; in 20:12 he gave people the ability to see and hear. The way the poor are treated matters to God (they are all his creatures, 16:4; 22:2; 29:13; those who mock the poor insult God, 14:31; 17:5; and those who are generous honour him, 14:31). Furthermore, he sees all (15:3) even into human hearts (5:21; 15:11) and he tests the human heart (16:2; 17:3; 21:2). He determines events (16:33; 20:24), often frustrating human plans (16:9; 19:21; 21:31).

Having a cluster of Yahweh sayings at the centre and seam of the largest collection in the book (15:33 – 16:9) implies that all the proverbs on either side of the seam need to be understood in the light of these theological truths, thus proposing a theological grounding for the sentence sayings. They are not just secular wisdom, good or bad; instead, they are observations that require the reader first to understand the bigger picture of where God fits in.

Lennart Boström notes that God is referred to by name throughout the book. Of the ninety-four references, twenty-one are in chapters 1 – 9; fifty-seven in 10:1 – 22:16; five in 22:17 – 24:34; seven in chapters 25 – 29 and four in chapters 30 – 31. Boström argues that God is pictured in Proverbs as both the supreme God (transcendent and sovereign) and as a personal God (seen in his attitude to the weak and to the righteous human). The idea of God as the sole Creator is not in dispute in the book, and hence creation theology is prominent. Proverbs views God as involved in the world and responsible for maintaining justice. He is simultaneously transcendent over, and engaged in, the world, intimately related to it and to individuals in it.14 The theological perspectives established by the prologue may not always be referred to specifically, but they are assumed, applied and unpacked in the many observations about how to choose wisdom and avoid folly in daily life.

Daniel Treier has undertaken an explicitly theological commentary on the text.15 His analysis of chapters 1 – 9 is guided by the theme of the ‘two ways’, which is a clear contrast drawn in the text. However, he also has a major focus on 8:22–36 because of its significance for later Christological debates (i.e. its significance for systematic theology, rather than because of its significance in the book).

Treier is at his most creative in suggesting a novel way of approaching chapters 10 – 29. Here he uses as his classification categories not topics but the classical virtues and vices. The four cardinal virtues (prudence, justice, temperance and fortitude) are derived from Greek thought, and the three theological virtues (faith, hope and charity) are derived from the Christian church during the Roman period. Thus, these are the virtues with a strong Greek aroma and a Latin aftertaste, having little real connection with Hebrew thinking. These seven virtues are matched by an equal number of capital vices (also called ‘cardinal’ or ‘deadly sins’), namely lust, gluttony, greed, sloth, wrath, envy and pride. Again these vices have been derived from Greek origins, but are shaped by Latin thought.

In the end Treier’s cardinal virtues and vices miss out on the fundamental relational dimension of Hebrew thought, as well as its social or community rather than individual focus. He majors on what kind of person should I be, rather than what kind of community should we be. In addition, from a cross-cultural point of view, his understanding echoes a modern Western right/wrong value system rather than an ANE honour/shame culture. In the end Treier’s analysis loses too much of the ecology (and so, theology) of the text.

Four specific areas of the book’s theology deserve further discussion: the idea of retribution, the fear of the Lord, God’s active involvement as Creator/Sustainer in everyday life, and the place of Proverbs in biblical theology.

The doctrine of retribution is a theory of justice often used in legal circles to justify the punishment of wrongdoers. While this dimension is present in the OT, the focus in the book of Proverbs is on the connections between our character and the consequences that follow. The way in which God orders the world (in Proverbs, largely behind the scenes rather than overtly) is that the righteous are rewarded and the wicked punished. It is part of the explanation of God’s sustaining the created, human world. In the books of the Law this retribution is seen more at a national level: God blesses his chosen people when they are obedient, and activates the covenant curses when they rebel (Deuteronomy 28).

Proverbs, however, is more concerned with the individual rather than the nation. In addition, their obligations to God and others are not specifically based on Israel’s covenant law, but on God’s broader ordering and sustaining of the creation.16 Furthermore, the link in Proverbs is not just between specific actions and consequences, but between a person’s character and the consequences that will flow.17 Proverbs simply insists that there is a correlation between character/actions and consequences without necessarily outlining the means used to reward or punish.

Proverbs clearly teaches both that the righteous will be rewarded and that the wicked will be punished. This can partly be seen in 3:9–10, where honouring God with your wealth and produce will lead to overflowing barns and bursting wine vats. In a cluster of Proverbs at the end of chapter 10 (10:27–32) there is a sustained contrast between a positive outcome for those of righteous character (life, joy, strength, security, wisdom, truth) with the opposite for the wicked. Righteousness and wickedness generally lead to different consequences (e.g. 10:3; 11:23).18 The purpose of this doctrine of retribution is to provide an incentive for readers and listeners to embrace the way of wisdom in our daily lives.

However, this does not mean that righteousness will always be rewarded and its opposite punished. Those who see an absolute correlation between our righteousness and our rewards have forgotten that proverbs were never intended to be promises or guarantees. This explains why we can find so-called ‘contradictory proverbs’ (e.g. 26:4, 5) in the book, because each proverb is not applicable in every situation or at all times. More specifically, the book itself nuances the connection between righteousness and rewards, and between bad outcomes and wickedness. So wealth may come from either wickedness (10:2; 16:8, 19; 22:16) or diligence (10:4; 12:27), and our wealth at any given instant cannot be a reliable measure of our righteousness or wisdom. There is even the explicit mention of the righteous falling seven times (24:16). If we are part of a city or nation or community, the wickedness of others can bring disaster (11:11), even if we are a righteous person. Moreover, justice can be perverted by false witness (12:17), greed, dishonesty or bribes (15:27; 16:28; 17:8; 20:10, 14, 17, 23), while lies and slander (which characterize a fool, 10:18) can bring personal and social calamity. Innocent people can meet a violent end (1:11; 6:17) or be cheated of their rights (17:23, 26; 18:5) or livelihood (13:23) (so Kidner 1985: 118). A (righteous) person may be shamed by a foolish wife (12:4), son (19:13), prostitute (22:14; 23:27) or dishonourable servant (14:35), while strife can be stirred up by a person with a hot temper (15:18). The poor can be people of integrity (19:1, 22).19 The book as a whole endorses the principle of retribution, but it does not describe all the ways in which God is at work in his world.

The fear of the Lord is the starting point or first principle of wisdom. Messenger (2015: 159) notes that ‘the central concern of the book is the call to live life in awe of God. This call opens the book (Prov. 1:7), pervades it (Prov. 9:10), and brings it to a close (Prov. 31:30).’ The frequency of the expression the fear of the Lord is quite remarkable, being found in the gateway chapters 1 – 9 (1:7, 29; 2:4–5; 8:13; 9:10; the verb fear the Lord is found in 3:7), the sentence sayings (10:27; 14:26–27; 15:16, 33; 16:6; 19:23; 22:4; 23:17; the verb is found in 24:21) and the epilogue (31:30).20 Furthermore, its structural location is very significant. The concentration of occurrences in the foundational first nine chapters is itself important, but made more so by a similar proverb at the climax to the prologue (1:7) and between the invitations of wisdom and folly in chapter 9 (9:10). These two instances bracket the first nine chapters, which also form an inclusio with its occurrence at the end of the epilogue (31:30). The concept is also structurally important in the Solomonic sayings, being found towards the beginning and end (10:27; 22:4), and concentrated in the theological seam in the middle (15:16, 33; 16:6; strengthened by the number of other Yahweh sayings here). Even the subsequent words of the wise (22:17 – 24:22) begin with the similar idea of trust . . . in the Lord (22:19), close with fear the Lord (24:21) and have an exhortation to continue in the fear of the Lord (23:17) in the middle. The expression is not found in the brief further sayings of the wise (24:23–34), the later proverbs edited in Hezekiah’s time (25 – 29) or the words of Agur and Lemuel (30:1 – 31:9), but the crucial importance of the idea has already been established. The important structural positioning of the motif testifies to the centrality of the idea in the book as a whole.

The concept of the fear of the Lord is potentially open to misunderstanding. It does not imply being terrified by, or living in dread of, God. Rather, it has a range of meanings that centre on respecting God as God and treating him as he deserves. It is this underlying attitude of treating God as God that is the only true foundation for knowledge and living wisely as outlined in the book, and is a necessary condition for living successfully in God’s world. This inner attitude is closely connected to humility (15:33; 22:4), or rightly acknowledging that the Lord is God in his world. Those who wish to be shaped by wisdom are urged to embrace this right response to God (1:29; 3:7; 24:21). It is the beginning or first principle of wisdom (1:7; 9:10), but is also our ongoing response as well (23:17). The fear of the Lord is the foundation for a godly character (2:4–5 in the setting of 2:1–11) and is a moral category that will involve the rejection of arrogance and evil actions (8:13; 16:6). As instruction in wisdom (15:33) and a fountain of life (14:27; see the parallel with the teaching of the wise in 13:14), it is to be prized highly, since it is a more valuable possession than earthly riches (15:16). It results in a satisfying life (19:23), and is amply rewarded (22:4). As such, it is fitting that the virtue of fearing the Lord (31:30) climaxes the description of wisdom lived out in practice in the closing poem of 31:10–31.

Murphy (1986: 88–89) noticed two key theological ideas in Proverbs. First, the creation theology of the book, which establishes that ‘Wisdom is more than well-turned nuggets of human observation.’ Second, there is a key concept that God (who in Israelite wisdom must be Yahweh) reveals himself in human experiences. Similarly, Brueggemann (2003: 307–308) has argued that ‘Wisdom theology in the book of Proverbs is thoroughly theological. That is, it refers every aspect of life to the rule of God.’ He comments, ‘The fact that the teaching is inductive and established case by case, however, makes the teaching no less formidable theologically, because wisdom asserts that the God who decrees and maintains a particular ordering of reality toward life is a sovereign beyond challenge whose will, purpose, and order cannot be defied or circumvented with impunity.’

In seeking to identify the theological content of the book, Van Leeuwen (2005: 638) has argued that ‘Proverbs raises the theological question of the relation of ordinary life in the cosmos to God the Creator.’ As can be seen in the thematic studies in the next section, the focus of the book does not centre on the covenant, the law or even Israel and its institutions. Rather, it concerns those areas of everyday life such as wealth, speech, families, friends, work and our inner goals (the heart) which make up ‘the good life’. Much of the rest of the OT deals with God’s active rule as King over his chosen people, living in (and sometimes travelling towards or exiled from) the Promised Land, and being under the authority of God’s law. Proverbs, like the other wisdom books, has a wider vista on all humanity, the whole earth (at times, the cosmos), and living in response to God’s ordering of his creation (see Wilson 2015: 310–312). God the Creator is pictured as the one who sustains and orders his creation, and it is in this everyday life context that we have to live wisely.

This makes the book of Proverbs a rich source of teaching about how to live in a godly and wise way in our daily lives. God is clearly the one in charge (16:1–2, 9), and he is actively at work in his work (16:4, 7). While the law is dominated by commands and prohibitions (‘you shall not . . .’) and the prophets thunder at the people ‘thus says the Lord’, Kidner (1964: 13) notes that there is in wisdom books like Proverbs a concern with those everyday details which are too small to be trapped in the mesh of the law or attacked by the broadsides of the prophets. Proverbs deals with how to approach God and especially other people, but in quite a distinctive way. It is less confined to religious actions, and more orientated to the whole of life – what we spend most of our time doing. This is why generations of believers have found it such a profitable book. Moreover, it is concerned with our character (see especially on ch. 2) and not simply with our external actions. Who we are counts just as much for Proverbs as what we do. Proverbs takes our faith out of our church buildings and into the world, arguing that God is interested in us living under his active kingly rule in that context as well. There are rich resources here for a theology of everyday life.

The Bible, including the OT, is about God revealing and establishing his active kingly rule (= the kingship or kingdom of God), teaching and enabling God’s people to live under this kingly rule. It outlines God’s people, living in God’s place, under God’s rule. As such, it concerns God’s active involvement in history, in creation, in everyday life, in the world, in God’s people, in the future – and outlining the implications of God’s kingly rule – for God’s people and for others, in terms of how we are to respond to him as King, how we are to live, what we are to look forward to, and back to. The Bible is not just about God, but about his ordering, ruling, controlling his creation and his people, regulating life in his creation and calling for response from people. It outlines God’s kingly rule past, present and future, exercised through special people and through his word, in the world and among his people, and climaxes in the life, death and victorious resurrection of Jesus.

What part does Proverbs play in such a biblical theology? It focuses on everyday life: what works, what brings success and so on. It speaks about God being in control, but not acting visibly in the world to accomplish his purposes. However, rather than God directly intervening as in the history books, there is a focus on the natural processes. In 10:3–4 God prospers the righteous, but it is achieved through their diligence. Similarly, the lazy will come to poverty through their slackness, although this is also the work of the Lord. Often Proverbs simply asserts that God does or will do something, without outlining the means he uses (e.g. 12:2–3; 15:25; 16:3, 5). There is no hint of God’s overt intervention, but in all this he is actively at work, achieving his outcomes and controlling these natural processes as he brings about his purposes behind the scenes. It is describing the work of the same God as the rest of the OT, but focuses on the regular and orderly patterns of his sustaining work, rather than on his more specific, spectacular redemptive activity that is dominant in much of the rest of the OT. Of course, other parts of the OT explore God’s work in creation, such as the creation accounts of Genesis 1 – 2, God’s power over creation in Exodus 1 – 15, some psalms (e.g. 19, 104), and even the image of the new creation in Isaiah 65:17–25. Proverbs mentions in passing God’s action in bringing creation into being (3:19–20; 8:22–31), but the main emphasis is on his sustaining activity. The one who brought creation into being now also keeps it going, and urges people to learn from how he sustains it.

Thus, Proverbs (as part of wisdom literature) adds a distinctive richness to a biblical understanding of God at work in his world. It must be read on its own terms first (so Longman 2006: 64), and in so doing it reveals that God’s purposes are broader than simply saving sinners. While this will always be at the heart of the Bible, God has seen fit to include a book like Proverbs which describes him as actively at work in shaping individuals and the community in accordance with his values, and giving much instruction for daily living. Since all of life must come under Christ’s lordship (since he is in Col. 1:15–20 Lord of both creation and redemption), then the teaching of Proverbs must be brought to the NT and reread in the light of Christ (Luke 24:27, 44). Jesus builds on the teaching of Proverbs (e.g. parts of the Sermon on the Mount) in arguing that our new life in Christ must result in a radically transformed way of daily living. Some later NT books develop that in terms of life in the church, as well as in our everyday lives in the world (e.g. James).21

Many preachers and teachers use thematic studies on the sentence sayings of the book (see Ministry issues, pp. 48–51). I will explore the issue of wealth and poverty at greater length as a guide for how this can be done, with briefer analyses of some other key themes.22

In Proverbs wealth is viewed positively, neutrally and negatively, and we must not simply ‘cherry-pick’ those sayings that suit us. Moreover, the explicit teaching of the book is that there are other matters that are of greater value than wealth.

The link between godliness and wealth is already clear in 3:9–10, where honouring the Lord with your wealth and produce leads to full storage barns and overflowing vats of wine. Wisdom is seen to be the possessor (and giver) of riches and enduring wealth (3:16; 8:18), although in these proverbs wisdom holds this wealth together with honour, righteousness and long life. This gift of wealth is viewed as an inheritance arranged by wisdom (8:21). Other sayings view riches as a blessing or reward from God (10:22; 13:21). The normal expectation according to 15:6 is that the righteous will receive treasure. However, Sandoval (2006: 156–157) notes that the proverbs which promise well-being, such as 11:18 and 15:6, require a figurative reading rather than one in dollar or shekel terms. They are true as generalizing proverbs, but should not be read as promises. Yet the normal pattern remains that embracing knowledge and wisdom will lead to riches (24:4).

So the book of Proverbs does make a connection between righteousness and wealth, and between wickedness and poverty, but it does much more than this. Waltke (2004: 463) notes that half the occurrences of wealth, hôn, in the Solomonic collection concern prizing wealth (10:15; 12:27; 13:7; 19:14; 29:3), and the other half make the balancing point of not trusting in it. Its teaching on riches is much more nuanced than is suggested by some proponents of prosperity theology.

At times, the book of Proverbs simply provides a descriptive, neutral or non-evaluative observation about money or wealth. Proverbs 10:15 observes that wealth can provide a certain measure of safety and security. This proverb is not arguing that people should trust in their wealth for security. It is simply observing that wealth provides insulation from setbacks in life, without any judgment about this being right or wrong. The proverb of verse 15a is used in 18:11–12 to warn against pride, but here it serves to ground the observation in verse 16 that the character of a person will determine whether wealth will be beneficial or harmful. Proverbs 14:20 observes that the rich have more friends than the poor (Murphy 1998: 105, ‘riches create differences in social life’), without any implication that this ought to be the case. There is no command to follow, or goal to strive for. The proverb just describes the reality that those who are rich can lavish good things on their friends, but a poor person has little to give. It is also clear that economic power is real. Proverbs 22:7 outlines a society stratified by power linked to money, but the proverb neither condemns nor commends it. It simply observes that economic power is part of reality, whether that be the greater opportunities the rich have compared with the poor, or the dependency that results when a person takes out a loan from another.

There are various observations that negate or significantly qualify a connection between righteousness and wealth. These fall into a number of groups. First, there are the many references to wicked people being wealthy. Second, there are examples of people who gain wealth wrongfully, such as through bribes, injustice, assault, adultery or even just too hastily. Corresponding to these are depictions of those who are poor, whose poverty is not due to unrighteousness. Lastly, there are some warnings about the dangers of wealth itself.

Yet the fact that Proverbs mentions those who are both wicked and rich makes it clear that there is no automatic connection between righteousness and wealth. If righteousness is always rewarded with riches, and wickedness punished by poverty, then there should be no wicked rich, but there are (11:7; 22:16; 28:6, 8, 22).

There are also a number of general descriptions of people wrongfully gaining wealth (10:2; 11:4; 21:6). Wealth cannot be pursued without weighing up the means used to attain it. Thus, we see the problem of wealth gained by bribes (17:8, 23; 29:4), dishonesty (20:10), injustice (18:5; 22:22, 28; 28:21), physical attacks on others (1:8–19; 16:19), adultery or prostitution (5:8–12; 6:29–32) and even acquired too hastily (13:11; 20:21; 28:20). The flip side of this is that there are those who are poor, not because of wickedness, but due to the wrong actions of others (13:23). It is clear, then, that Proverbs does not exclusively teach that God will always financially reward the wise/righteous and financially punish the foolish/wicked. Life does not work that way, and neither does the book of Proverbs.

So people are warned not to trust in riches (11:28) since God is the one who is to be trusted (16:20; 28:25; 29:25). Riches are seen to be fleeting (23:4–5). One of the seductions of wealth is that it offers the lure of becoming self-sufficient (18:10–11), presumably by insulating the possessor from having to worry about daily needs. Yet sometimes having wealth leads to greater danger, such as being the target of kidnappers (13:8).

The book of Proverbs also insists that there are other things more valuable than ‘mere money’. Some obvious examples will suffice: wisdom is of greater worth than wealth (8:10–11, 19), as are wholesome relationships (17:1), godly character (22:1; 28:6), righteousness (11:4) and honour (11:16). Furthermore, wealth is only of value if it is combined with the more crucial category of a godly character, grounded in the fear of the Lord, and issuing in a life of justice and righteousness. Thus, if wisdom is allowed to shape our character, then the way we use wealth must be consistent with a godly character. When it comes to money, that will involve not being greedy, or coveting what others have, not having as our goal in life to make as much money as possible (i.e. worshipping it). It will lead us to think in community terms (a godly character builds up community), and be committed to justice and righteousness. Lucas (2015: 293) notes that the prologue sets out the purpose of the book and ‘there is no indication that it offers the attainment of material wealth.’ Instead, ‘the point the prologue makes is that what you are is foundational to the good life. What you have is a secondary matter.’

A closer look at 3:1–12 is in order. Waltke (2004: 238–240) helpfully shows that verses 1–10 are a celebration of what flows from the changed character outlined in chapter 2. In the odd verses (vv. 1, 3, 5, 7, 9), he discerns the outline of a godly character, while the even verses (vv. 2, 4, 6, 8, 10) draw attention to the outcomes that will follow. When read together, the even-numbered verses announce that those who are shaped by wisdom will receive a long and peace-filled life, favour and success in the sight of both God and others, a straight path through life, physical health and healing, and abundant material prosperity. But that cannot be independent of trusting in the Lord (v. 5), fearing the Lord (v. 7) and honouring the Lord (v. 9). Indeed, the material prosperity in 3:9–10 is not linked with the size of a monetary gift, but with character (honouring the Lord, v. 9; see also trust in the Lord, v. 5; fear the Lord, v. 7). Lucas (2015: 295) comments that ‘the enjoyment of wealth is subordinated to, and dependent on, honouring the Lord.’ Of course, there is no promise of abundant wealth in 3:9–10, any more than there was a promise of long life and peace in 3:2. In fact, verses 1–10 are also followed immediately by verses 11–12, which address the situation when the prosperity, life and success of verses 1–10 do not seem to be happening.

While the faithful use of material possessions often leads to further material blessing (3:9–10), this must always be based on honouring the Lord (3:9). The depiction of character in Proverbs would involve not wanting to give wealth an inordinate place in one’s desires, so that truly honouring God would entail keeping your life free from the love of money. One clear goal of ‘the good life’ is the virtue of contentment (15:16–17; 16:8; 30:8–9).

In the book as a whole, the appropriate response to gaining wealth is not the accumulation of further riches, but rather generosity to those in need (22:9). It is clear in 11:24–26 that any growth in wealth is simply an added bonus and not the goal of the enterprise (see also 14:22). Proverbs, like the rest of the OT, endorses care for, rather than exploitation of, the poor and needy in their own community (14:31; 19:17; 22:22–23; 31:20).

Proverbs 6:16–19 lists a series of matters that are abominable to the Lord, and these climax (or reach their low point) in a person who stirs up division between brothers. Hybels (1988: 161–193) suggests that forging strong families is a key theme of the book. However, it seems to talk more about godly families – those which have been worked over or shaped by God. Godly families are certainly important for the good life. Many Western cultures define a good family as one where children are well provided for and given a lot of opportunities and experiences so that they can reach their full potential. Proverbs thinks more in terms of training children to respect others, handing down the truths of the faith and modelling the service of God. The goal is that children become people who fear the Lord and develop a godly character.

Parents have a responsibility to teach and train their children. This is part of our role and responsibility before God, and given to both fathers and mothers (1:8). One well-known saying is Train up a child in the way he should go; even when he is old he will not depart from it (22:6). While this is not a guarantee (remember it is a proverb, not a promise) that the children of godly parents will become believers themselves, it does give parents encouragement that diligent parenting is valuable and has enduring effects. Notwithstanding the exceptions that we all know, it is generally true that good teaching and discipline in a family will strike a positive response from a child. However, this proverb should not be pressed so far that we ignore either the sovereign election of God, or the real responsibility of children themselves. Proverbs 22:15 points out that folly is bound up in the heart of a child. A child can be too opinionated to learn (13:1; 17:21), idle (10:5) or self-indulgent (29:3). Children might mock or curse (30:11, 17) and waste their parents’ money (28:24; 29:3). It is unkind to leave them like that, and so parents have a responsibility to teach and train their children (23:13–14).

References to the rod are not primarily an endorsement of corporal punishment, but rather a call to teach and correct those in our charge. In ancient Israel it involved the use of the rod, but each generation needs to apply the principle of correcting children in ways that work best in their society. The warning that if we do not use the rod, we hate the child (13:24; 29:15, 17) is really an outworking of the book’s real concern to mould children to live wisely. A hard road to wisdom is better than a soft road to death (19:18; 23:14), and their character needs shaping (22:15). The encouragement of training a child (22:6) is based on the view that character is like a plant that grows better by pruning (5:11, 12; 15:32, 33).

Yet there is also the positive dimension of encouraging the next generation. We do not only prune plants, but also fertilize, feed and water them. With our children we train them by instruction (7:2, 3), having the aim of equipping them for life (3:23; 4:8–9, 12). Of course, parents must themselves model godly behaviour. As 20:7 expresses it,

The righteous who walks in his integrity –

blessed are his children after him!

The children of godly parents are blessed because they have an example to follow. Thus the glory of children is their fathers (17:6b).

Children – even youths or adult children – must respect their parents and their teaching. They are called to give due honour to their parents (23:22), which at least involves listening to them and not despising them (19:26; 20:20; 28:24; 30:11). The consequences of mocking or scorning obedience to parents are set out memorably in 30:17! So children must learn to live wisely day by day, and to adopt healthy patterns for the rest of their lives (23:19–21). The ideal is to live in such a way that their (godly) parents or grandparents delight in them (10:1; 15:20; 23:24–25; 17:6a). This focus on others rather than self is part of the counter-cultural summons of the book, then and especially now. Godly families are set in the wider context of a transformed community.

The book of Proverbs does not aim to give a comprehensive study of marriage, but it does shed light on some aspects of this particular relationship. A few matters are dealt with in passing, such as the covenantal nature of marriage (2:17), even if issues like divorce are not covered. Again, the marriages in view are between one man and one woman (5:15–20; 31:10–31), but there is no explicit polemic against polygamy, let alone the contemporary issue of same-sex marriage. There is much emphasis on the loose or foreign woman (including the prostitute and adulteress) in chapters 1 – 9 (e.g. 2:16–19; 5:1–23; 6:20–35; 7:1–27; 9:13–18). While these passages are primarily about folly personified in its clearest example, they do also disclose something about sexual relationships outside of marriage. This is not largely the focus of the later sentence sayings, but occasionally surfaces (e.g. 22:14; 23:27–28; 30:20). It is clear that young men are warned against both the prostitute and the adulteress, and that succumbing to either is a failure of both wisdom and discipline (e.g. 5:12–13, 23). However, more significant is the positive endorsement of sex (developed in the Song of Songs) within the context of marriage in 5:15–20. The explicit commendation of one’s wife in 5:18–19 suggests that chapters 5 – 7 can be used to speak not only about folly personified but also sexual temptation and transgression.

A spouse is a good gift from God (18:22; 19:14; 30:18–19), and men are urged not to stray from their home (27:8). Young people are urged to choose their spouse carefully, as a good wife enriches a person’s life (12:4), just as a poor choice makes life constantly difficult (e.g. 11:22; 19:13; 21:9, 19; 25:24; 27:15–16).23 Of course, many of the truths about friendship will apply to marriage as well. The book concludes with a long poem about an excellent wife (31:10–31). While this concluding section is mainly intended to exemplify wisdom (a counterbalance to folly ‘enfleshed’ in chapters 5 – 7), it also draws attention to a number of positive attributes in a wife (see below on the ‘good life’). Of special significance is the statement that she fears the Lord (31:30), which presumably is the foundation for her actions full of energy, care and initiative.

We need godly advice about friendship because this is a key area in which we often hurt others by our shortcomings. Indeed, most of us can tell of times when we chose the wrong friends and got hurt.24 Given the increasing strength of peer pressure, this teaching is more vital than ever. The opening chapters of the book have a repeated emphasis on young men avoiding bad male company. The negative counter-example to embracing wisdom (1:20–33; 4:10–13) is joining a gang (1:8–19; 4:14–17), while the result of the shaped character (2:1–11) is being rescued from wicked men and their ways (2:12–15). The danger of simply drifting into a bad friendship is also enunciated later in the book (13:20; 28:7b).

What kind of friend is commended in the book? A key feature of a good friend is loyalty. A true friend has an ongoing commitment and is not put off by adversity (loves at all times, 17:17). Such a friend can establish a relationship that is even stronger than our family bonds (18:24). The relationship between David and Jonathan was this type of friendship (1 Sam. 20, especially vv. 17, 41–42). They do not cease to be friends when it no longer suits them, or they no longer receive material benefit from it (e.g. gifts, 19:6). Thus, the closeness of our relationships is more important than the number of friendships we have (18:24). So friends are to be greatly valued (27:10).

Genuine or earnest advice is a valuable aspect of friendship (27:9). The best kind of friend is not one who will always agree with, flatter or affirm us, but rather one who has our best interests at heart. Thus, our friends will be those who will be honest and open with us. Kidner (1964: 44–45) reminds us that they need to say both ‘yes’ and ‘no’ – ‘yes’ to a proper request (3:27–28), but ‘no’ when it would lead to folly (6:1–5). We do not benefit from deceptive flattery (26:24–25), but we can certainly grow in character when those committed to us are brave enough to rebuke and challenge us (27:5–6; 28:23). Our wisdom ‘sharpness’ grows as we interact with our friends, like iron sharpening iron (27:17). Friends do not simply indulge us, but also hold us accountable. The words a friend uses may hurt (wound, 27:6), but they come from a faithful desire that we grow. As our friends help us to grow in wisdom, they will no doubt also help us to grow in our relationship with God.

Finally, some characteristics of others militate against establishing valuable friendships. Thus, a gossip is a person to be avoided (16:28; 17:9; 20:19; 26:20–21). Gossip is often a ‘respectable sin’ in Christian circles, sometimes disguised by ‘sharing a matter for prayer’, but it is destructive of community and of faith.

Someone who is inconsiderate or insensitive will make a poor friend. A person loudly ‘blessing’ another early in the morning (the community equivalent of waking a teenager), will not be appreciated (27:14). Humour is a great source of enjoyment in relationships, but one who does not know when to stop, or how to use humour, will also make a poor friend (26:18–19). Saying ‘I was only joking’ does not fix the hurt or betrayal. Other indications of a poor friend include overstaying a welcome (25:17) and being insensitive to someone’s pain (25:20).

Friendship is one of God’s good gifts and is too important a gift to treat lightly. Proverbs urges us to be wise in the friends we choose, for they will influence us greatly, for good or bad. We need to choose those friends who will help make our character and actions reflect the values of wisdom. Yet, in the end, the emphasis should fall not on how we should choose our friends, but on what kind of friend we should be to others (3:27). Lucas (2015: 239) comments, ‘We are not all parents, but all are children. We are not all married but are all family members. So, we all can play our part in creating functional families.’

The discussion of family and friends leads naturally to the issue of speech, possibly the most prominent theme in the book. While a contemporary English proverb says that ‘sticks and stones may break my bones, but words will never hurt me’, the book of Proverbs sees that speech has great power for both good and harm. Words have the power to bring life and cause death (18:21; 12:6); they can cause healing or inflict damage like a sword (12:18; 14:25; 15:4); they can restore joy to an anxious person (12:25). They are seldom ‘mere words’. Grace-filled words have a sweetness that revives and restores (16:24), but worthless speech is like a scorching fire, and brings strife and division (16:27–28). Wisdom and folly personified are able to be distinguished by their life-giving or life-taking words (9:5–6, 17–18). Wise words reflect what we are like inside – wise of heart (16:23; 18:4).

Proverbs both warns against the wrong use of words, and affirms the right use of words. In 6:16–19 three out of the seven things God hates have to do with false speech (a lying tongue, a false witness who breathes out lies and one who sows discord among brothers). A worthless or wicked person is characterized by crooked speech (6:12). Scoffers epitomize the wrong use of words, as their mocking speech leads to quarrels, strife and abuse (22:10; 29:8). They react angrily to correction (9:7–8a; 15:12), making them an abomination (24:9), spoilt by their pride and arrogance (21:24).25 Close to the scoffer are those who slander or insult others (10:18b). Their words reveal other people’s secrets (11:13), or wrongly curse those who deserve their loyalty (20:20).

There is a significant focus on lying in the book. The Lord hates lies and false witness (6:17, 19; 12:22), and the righteous should do so too (13:5). There are explicit or implied exhortations not to speak crookedly or lie (4:24; 12:17, 19). Agur asks for two things: neither poverty nor riches, and falsehood and lying to be removed far from him (30:7–8). Telling lies is harmful (25:18), and we should not lie to get out of an obligation (3:28; 12:13).26 It has been pointed out that ‘Throughout the book of Proverbs, the importance of telling the truth is a steady drumbeat’ (Messenger 2015: 164). It is better to be poor than a liar (19:22), which includes not keeping a promise (25:14). Lying is closely related to its more socially acceptable cousin – flattery (26:28; 28:23). This too should not characterize those who want to walk in the way of wisdom. Furthermore, we should not listen to, or tolerate, the mischievous lies of others (17:4).

There are a number of other ways in which words can be abused. We are not to use them to boast about ourselves (27:2), or to show off before others (12:23). Nor are we to speak too hastily before we have heard the full picture (18:13, 17; 29:20). A wise character is needed to know when to speak and when to refrain from speaking (26:4, 5). Words used in gossip are harmful and pointless (11:13; 18:8; 26:22), and speaking behind the backs of others is destructive (25:23). We should beware of the seductive use of words by those enticing us to do wrong. This is most clearly seen in the book in the figure of the forbidden woman with her silky smooth words (2:16; 5:3; 6:24; 7:21–22; 22:14), but others can also cause damage by disguising their harmfulness behind gracious words (e.g. 26:23–26).

However, there is also much written in the book about how words are to be used in a positive way. Indeed, the assumption is that godly speech will prevail (10:31). We need to listen to, and be shaped by, the words of wisdom as she speaks (e.g. 1:20–21; 2:1–2; 8:1–11). Wisdom’s words are true and life-giving (8:7–8, 32–35), just as every word from God is true (30:5–6). Our righteous words are designed to give life (10:11), commend knowledge (15:2) and show a winsome grace (22:11). We are to speak up for the helpless poor and needy (31:8–9), and utter true words of confession before God and others when we have done wrong (28:13). Self-control should be a feature of our speech, as we carefully weigh up when to speak and what to say (13:3; 17:27–28; 21:23). This may often lead to us speaking fewer words, as we ponder carefully how to answer a person (15:28). With fewer words we can pay more attention to their quality or truth or helpfulness (10:19). A timely comment or ‘word in season’ can be very beneficial (15:23; 25:11).

Certainly, our words should be honest (24:26), although this does not preclude us from giving correction when needed (27:5). Although our words may seek to be persuasive (16:21, 23), they must also be gentle (15:1, 4) and gracious (16:24; 31:26). A civil tongue should not simply be dismissed as a relic of a bygone era. There should be a calmness (or cool spirit, 17:27) in how we speak, as we attempt to do good and bring wholeness with our words.

The focus on daily life in Proverbs makes it a rich source of teaching about the neglected topic of daily work.27 A counterpoint to this information about work is the comic portrayal of the one who refuses to work – the lazy person or sluggard.28 The two themes are sometimes discussed separately (e.g. hard work in 27:23–27; laziness in 26:13–16), but also woven together into one for a sharper analysis (e.g. 6:6–11).

On the topic of work, the book deals extensively with a wide range of workplaces: ‘agriculture, animal husbandry, textile and clothing manufacture, trade, transportation, military affairs, governance, courts of law, homemaking, raising children, education, construction and others’ (Messenger 2015: 159–160). The woman of 31:10–31 is active in many of these areas, making it clear that the issue of work is a vital one for both men and women. The book contains reflections both on work itself, and on how workers should work.

Work is seen as the appropriate way to provide wealth and sustenance (10:4; 12:11; 28:19). It is, at the very least, a fitting way to avoid poverty (14:23), and a failure to work will result in a person not having enough to eat (20:4). A memorable example is given of the hard-working ant (6:6–8) who works without a supervisor forcing her to focus, and who plans ahead for future lean times. An interesting feature of the book of Proverbs is that there is almost no focus on job satisfaction, nor of the value of work or the danger of overworking. However, it affirms the rightness of working skilfully (i.e. performing a job well), and the observation is made that this will lead to professional advancement in future (22:29). It also indicates that work to meet our basic needs should take priority over work to make life more comfortable (24:27).

There is much greater emphasis on the attitudes we bring to our work. The Theology of Work Project helpfully draws out a number of descriptions of the wise worker (Messenger 2015: 161–186). Those shaped by wisdom will be trustworthy or honest in their work, both in their words (8:6–7; 10:18–19; 12:17–20; 14:25; 21:6) and actions (11:1; 16:11; 23:10–11). They will be diligent, working hard (10:4–5), planning for the future (6:6–8; 21:5; 24:27; 27:23–27) and contributing to the profitability of the workplace (18:9; 31:18a). Such a worker will also be shrewd (1:4–5) in the sense of showing good judgment (31:13–14), preparing for contingencies (31:21–22) and seeking good advice (15:22; 20:18). Wise workers will be both generous (11:24–26; 19:17; 28:27) and just (3:27–28; 16:8; 22:8–9, 16, 22–23). They will be careful in their speech (21:23), avoiding gossip (11:12–13; 16:27–28; 18:6–8; 20:19; 26:20–21), speaking kindly (15:1, 18; 16:32; 31:26) and using words to build up others (12:25; 15:4; 18:21). Finally, they will be modest rather than proud (11:2; 16:18–19; 21:4; 29:23) or even wealth-seeking (11:28; 22:1; 23:4; 28:22; 30:8–9).

On the issue of laziness, the book concentrates on the lazy person or sluggard rather than laziness itself.29 Longman (2006: 561) notes that ‘Proverbs is intolerant of lazy people; they are considered the epitome of folly.’ Sluggards are caricatured throughout the book. They make up fanciful stories (There is a lion in the road/outside, 22:13; 26:13) to justify their inactivity.30 They reach out for food but cannot be bothered to bring the food back to their mouth (26:15). Their only exercise is to turn over in bed (26:14). The sluggard owns a vineyard, but neglects it so much (almost as if he did not notice) that it becomes overgrown with thorns and nettles, and its protective walls are broken down (24:30–31). No other stereotype is denigrated quite as much as the lazy person. Dell (2002: 37) expresses it well: ‘Laziness is a barren land that leads nowhere.’ In an honour/shame culture, the lazy bring shame on their family (10:5) and destroy their family’s inheritance (19:13–15; 24:30–31).

Kidner (1964: 42, followed by Lucas 2015: 228) suggests that the sluggard’s problem is threefold: ‘he will not begin things . . . he will not finish things . . . he will not face things’. He prefers sleep to effort (6:9–10; 24:33); he is an irritant to those around him (10:26, like vinegar to the teeth and smoke to the eyes); he is unsatisfied (13:4; 21:25–26) and destructive (18:9); and is heading nowhere in life (12:24; 24:34). Waltke (2004: 115) notes that the sluggard is never equated with the poor whom we should help, and that the only thing he has plenty of is poverty (28:19). Being lazy causes us to miss out on the good life which hard work is intended to bring about.

The whole of the book of Proverbs could be covered under the heading of ‘the good life’ (see e.g. Whybray 2002: 161–185). While this would be both worthwhile and comprehensive, my aim in this section is to examine one cameo – that of the excellent wife in 31:10–31 – as a source of insights about the good life according to the book. This could be a very fruitful topic for a final sermon or Bible study on the book. This approach is based on the assumption (argued for in the commentary) that the wife of 31:10–31 is not simply a (possibly composite and certainly overwhelming) model of what a wife should be like, but is rather a worked example of what it means to live wisely in the world. As such, it is a useful source of instruction for both men and women who seek to live the ‘good life’.

She embodies many of the themes picked up in this section of the commentary. The Proverbs 31 woman models the achievement of a secure life for herself and her dependants, principally security from a life of poverty. She gains prosperity because of her entrepreneurial skills, hard, persistent work, good management and her business acumen (vv. 13–19, 24, 27). She trades and transports her goods (vv. 13–14, 24), buys land and starts a business (v. 16). She rises early (v. 15a), works until late (v. 18b) and provides food for her family and servants (v. 15b) as well as clothing (vv. 17, 19). Verse 27 summarizes her diligence in work:

She looks well to the ways of her household

and does not eat the bread of idleness.