PEOPLE SKILLS

LESSONS

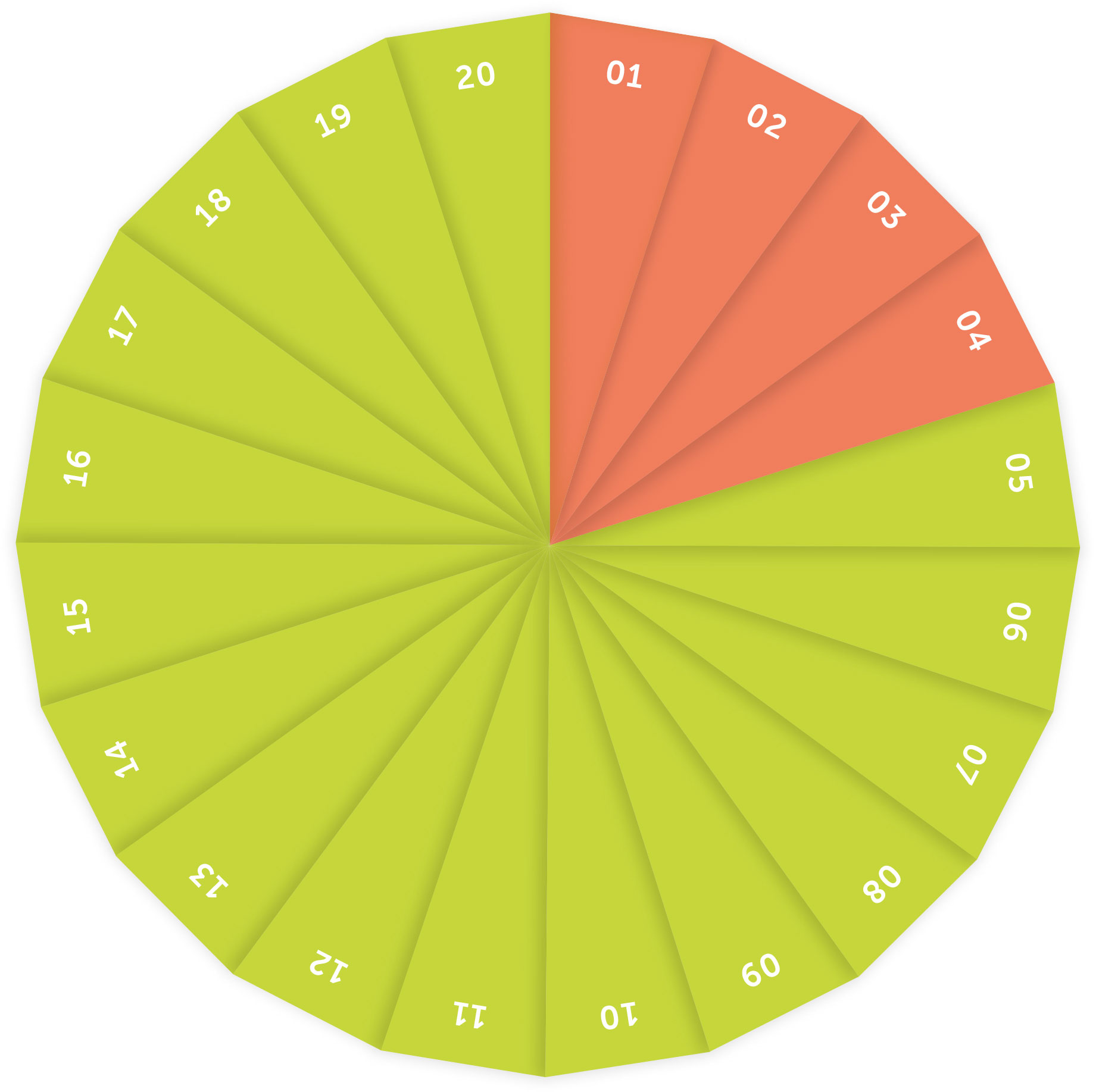

01 HOW TO ARGUE

Arguments are essential for generating new ideas. So is it weird to think they’re oppositional?

02 TELLING THE TRUTH

Is it ever okay to lie? Can a lie be a victimless act? Immanuel Kant says ‘no’ – should we trust him?

03 RESPECT

We respect different things; laws, nature and people. Do we respect them in the same way?

04 THE LIMITS OF LOYALTY

It seems obvious that loyalty is a virtue and disloyalty is a failing. But just because something’s obvious doesn’t make it true.

‘Morally as well as physically, there is only one world, and we all have to live in it.’

Mary Midgley

In this chapter we’re going to look at what folk in management would call ‘people skills’: interpersonal relationships. How do we interact with others? And, importantly, can philosophy help us see better ways of doing so? The Lessons focus on ethical behaviours we exhibit – and sometimes fail to exhibit – in our day-to-day dealings with other people. Whether at home or at work, out shopping or on the bus, the way we interact with other human beings is unendingly fascinating. Even the most humdrum encounter can benefit from philosophical investigation.

Say you’re arguing with your buddy over what to have for dinner – pizza or curry? How are you arguing? And why? Are you open to having your mind changed?

What about if you want to call in sick – is it bad to lie to your boss? Even if they don’t find out, what happens when you corrupt the capital T: Truth?

And think of all the times you’re told to ‘respect your parents’. Is this just parental propaganda? In order to know whether it’s sound advice, we have to work out what ‘respect’ is, and when and whether it’s appropriate.

Loyalty is another issue. When our friends criticize us to other people, we think they’re being ‘disloyal’. We rarely stop to wonder whether what they’ve said is justified. Maybe disloyalty isn’t such a bad thing …

In each situation, philosophical examination can help us understand what’s going on, and whether it might be ethical or unethical, effective or ineffective. Each of the lessons can be read independently of the others, although there are not insignificant links between them. At the end of the chapter, we’ll look at the lessons we’ve learned and start building our philosophical toolkit.

HOW TO ARGUE

Argument is a blood sport – that’s how many of us see it at any rate. We talk about engaging in a ‘battle of wits’, delivering ‘killer blows’ or seeing ‘fatal flaws’ in other people’s positions. When you describe the ‘cut and thrust’ of debate, you’re describing people stabbing each other – which is, it must be said, pretty grisly stuff.

Of course, these are metaphors. Things might get heated, but you tend not to literally shoot down your opponent in the middle of a conversation. In fact, a lot of the time arguments are amicable; it’s not uncommon to actively enjoy the parry and riposte element, in the same way you might enjoy a game of ping-pong. And like competitive sports, we think of arguments as things we can win or lose. If you’ve prepared your defences well and speak with sufficient dexterity, you can vanquish your adversary. You can dazzle them with rhetoric, undermine their premises or simply shout them down. It doesn’t much matter how you do it – the aim, we think, is to triumph.

But is this central to what an argument is?

The answer to this question depends, predictably, on the context in which the argument is taking place. If you’re in a debating squad preparing for a semi-final, it’s very much expected that there will be adversaries and, ultimately, a victor. Points are scored. There are judges to adjudicate. You might, if you’re lucky, even win a prize at the end.

Sadly, not all arguments work like this – most of the time we don’t get prizes. More importantly, the arguments we engage with in our daily lives are rarely so cut and dried or as static as they are in competitions.

Consider the structure of arguments. There are ‘premises’ – for example, the claims that ‘all humans are mortal’ and ‘Rebecca is a human’. And there’s a ‘conclusion’ that’s supposed to follow from the premises, such as ‘Rebecca is mortal’. In a competitive debate, you’re assigned a pre-established conclusion, like ‘Money is evil’, and you’re supposed to defend it without compromise while undermining your adversary (who holds the opposite view). There are various ways to argue that money is evil, and the debaters can deploy different premises, but ultimately they can’t relinquish their conclusion. They have to hold their position. If they don’t, we can’t say whether the debate has been won or lost.

WINNING FROM SOLVING

So here are two different forms of argument. On the one hand, an argument can be a kind of game, to be won or lost. On the other, an argument can be a way of problem-solving or exploring ideas. There are no winners per se, and participants don’t lose anything if they relinquish their original position.

Take a moment to think about how you normally argue. Do you argue to win? This is how a lot of people – from philosophers to lawyers and politicians – are trained. And it’s significant that this approach puts up tangible obstacles to understanding. The game requires you to defend your starting point, even in the face of good evidence to relinquish it. In some sense, this leads to what we might call ‘epistemic losses’, a setback in what you know. Even on its own terms, winning isn’t quite what it’s cracked up to be. Phyllis Rooney, in her paper ‘Philosophy, Adversarial Argumentation, and Embattled Reason’ (2010), puts this point well:

‘I lose the argument and you win … But surely I am the one who has made the epistemic gain, however small. I have replaced a probably false belief with a probably true one, and you have made no such gain…’

TELLING THE TRUTH

Immanuel Kant was nothing if not ambitious; in his book Groundwork of the Metaphysics of Morals (1785), he aimed to map out the structure of what he saw to be an objective moral reality. He claimed that there are incontrovertible moral facts – some acts are just always going to be wrong (murder most foul). There’s no wishy-washy, hand-waving ‘matter of opinion’. Moral truths do not depend on your perspective; they’re facts, wherever you’re standing.

It was this objective moral reality that he took himself to be tapping into with his concept of the ‘categorical imperative’. It’s a multifaceted notion of what it is, categorically, imperative that people do if they are to be moral. It’s one concept, a single, formal moral law, but it has different formulations. For the sake of present purposes, we can focus on the first two. To begin with, we’ve got the Principle of Universality, which states:

‘Act only according to that maxim whereby you can at the same time will that it should become a universal law.’

Kant isn’t really known for snappy writing – but in essence, this is a version of the ‘do unto others’ idea that you find in most religions. When you act in a certain way, you should consider whether it would be okay if everyone acted in that way. Say you decide to start filching other people’s chocolates – would it be okay if everybody did that? How would we get by if everyone was always filching everyone else’s chocolates (or money, or lives)?

The second formulation is known as the Principle of Humanity and states, roughly, that you should always treat others as ‘ends in themselves’ rather than as means to some end of your own. When dealing with friends and strangers, you have always to bear in mind that they’ve got their own lives, with their own hopes and dreams (and they must recognize that you have all of these things too). At the centre of Kant’s ethical system is the thought that we must respect the dignity and equality of human beings. If we fail to do so, if we use other people, we commit a moral violation.

Imagine, for instance, that you want to impress your boss by making your work-mate look like an idiot. Even if you don’t hold a particular grudge against Gilbert, you’d be failing to acknowledge his humanity; you’d be treating him as a stepping stone, not a person.

Kant’s moral system has its drawbacks. For one thing, as Lewis R. Gordon has pointed out (and we’ll see in Lesson 13), the man was a horrible racist – so his claims about the importance of universal respect for human beings seem hypocritical at best. For another thing, his picture is hugely formalistic. In claiming that there’s an objective moral reality, he paints our ethical world in black and white with no shades of grey.

However, despite these failings, his categorial imperitive has been hugely influential – not least because it aspires to flesh out a moral system without appear to theology. His Groundwork is an exercise in reason alone – so it speaks equally, he contends, to all human beings.

AIMING FOR TRUTH

There are a whole host of lies you can tell. You’ve got your little white lies and your whoppers, and typically we think some are worse than others. If you told me you don’t like asparagus, but secretly you do, I wouldn’t mind too much. If you told me you haven’t murdered anyone when actually you have – well, that’s another matter. Some lies seem to be more serious than others.

Kant, however, thinks all lies are equally bad – because lying, as an act, violates the second formulation of the categorical imperative, The Principle of Humanity. For Kant, human dignity and equality are of the utmost importance. We should never treat humans, he says, as anything less than what they are – free, rational agents with unique and self-governable lives. When you lie to a human, you’ve stopped treating them in this way because you’ve deprived them of the ability to assess a situation rationally and to respond to it freely.

RESPECT

Respect each other. That seems like a fairly good rule of thumb for our everyday interactions. ‘Love each other’ isn’t always workable, since love isn’t necessarily the kind of thing you can turn on or off. And ‘tolerate each other’ isn’t much better; you tolerate or ignore bad smells, and treating people like bad smells is a terrible rule of thumb – it doesn’t foster understanding or lead to harmonious living.

But is everyone worthy of respect? What about racists? Homophobes and sexists? Should we respect those who spout prejudice? If you find yourself faced with a bigot spewing dangerous hate speech, I’m guessing you’re going to find it hard to ‘respect’ them. So maybe we think there are people who aren’t worthy of respect?

Maybe … but let’s think a little harder about the issue.

Unless you lead an unbelievably sheltered life, it’s easy to find yourself confronted by people whose views you fundamentally disagree with. Arguments often result. And sometimes these arguments escalate because, in spite of your best efforts, it appears impossible to find common ground. There’s no compromise. You don’t just disagree with them, you think their views are dangerous and should be called out as such. They think, for example, that women are genetically configured to do housework – you think this is an abhorrent and ridiculous thing to say.

How does all this square with the seemingly sensible claim that we should ‘respect each other’?

Well, what is respect exactly? We respect different things in different ways. We respect nature (like the sea and its terrifying power), and concepts (like the speed limit and the law). ‘Respect’ can mean ‘don’t underestimate’; don’t underestimate the ocean and its ability to pulverize your boat. It can be a call to recognize the importance of something, and the consequences if you fail to do so. The speed limit is an important part of traffic regulations – if you don’t respect it, bad things happen.

And of course, we respect people too – also in a variety of ways. If you say, ‘I respect Martin Luther King Jr’, that would likely mean you admire him. But not everyone is so admirable. The suggestion above that we should ‘respect each other’ uses ‘respect’ in a slightly different sense. This usage is closer to what we were talking about in Lesson 2; when we respect people, we treat them as ends in themselves. We treat them as unique entities that have value in and of themselves. The political philosopher Kwame Anthony Appiah connects respect with the notion of human dignity. We’re all humans, he says, irrespective of our political views – and we need to recognize this when we’re interacting with one another. It’s not what we say that garners respect, in this sense, but what we are.

I RESPECTFULLY DISAGREE

Let’s return to the bigot. Undignified as they may seem, they’re still human and possessors of human dignity. In fact, we should probably stop calling them a ‘bigot’. It’s not helpful. Despite all the hateful things they say, they’re worthy of our respect (if not our admiration).

What does this mean in practical terms? What should we do when faced with people who say atrocious things? Shout? Jeer? Throw rotten fruit? No, says Appiah. If you respect them in this philosophical sense, then you’ll talk to them about their ideas.

It is, Appiah says in his essay ‘Relativism and Cross-Cultural Understanding’ (2010), ‘better to treat one another’s moral beliefs as responsive to reasons, because to treat a person’s moral views as bare facts about them, ungrounded in reasons, is to treat them with disrespect.’ If you respect someone, this involves seeing them as human, as beings with a capacity for thought and self-determination, as responsive to reasons. They’re more than just by-products of a cultural milieu. They’re people who can assess facts and analyze them, and come to judgments for themselves.

Imagine your grandmother says that being gay is ‘wicked’. Now, you love your grandmother but it’s a horrible thing to hear. So what do you do? Well, on the one hand you could just shrug – ‘She’s a product of her time’, you tell your friends, ‘She doesn’t know any better’. That, thinks Appiah, would be to treat your grandmother with disrespect. Of course, like anyone, there are deep-seated, culturally located reasons why she says the things she does. But your grandmother is human too. She has the capacity to think and reason, and form decisions for herself. If you respect her, and see her as a possessor of human dignity, you’ll talk to her and explain, as well as you can, why it’s hurtful and wrong to say that being gay is wicked. Her moral views are not bare facts about her.

When you revert to calling someone an idiot or close down a discussion, you’re being disrespectful insofar as you’re seeing your interlocutor as someone who can’t be reasoned with. It might be that, in the end, the obstacles are too great and neither of you can effectively communicate your rationale for the beliefs. Appiah’s point, however, is that it’s crucial to give the person the benefit of the doubt and to expect the same in return. You have to make yourself responsive to reasons, and so should whoever you’re talking to. It’s respect in this sense that one should aim for in arguments.

THE LIMITS OF LOYALTY

When was the last time you felt betrayed? Have a good think … got it? It’s a horrible feeling, isn’t it? Really gut-churning. It’s tremendously upsetting to discover someone you trusted has abused that trust. The connection you thought you had has been severed, perhaps irrevocably, and the time, effort and love that’s gone into a relationship has all gone to waste.

Betrayal comes in many forms. You can betray your partner by hooking up with others; you can betray your country by selling its secrets; you can betray your friends by talking dirt about them behind their backs. You can betray yourself too, by failing to live up to the principles you tell yourself to abide by.

The harmful effects of these betrayals can be far-reaching. If you betray your partner, you imperil your relationship. You also imperil future relationships – if you’ve cheated on someone you love, who’s to say you won’t do so again? You damage your status as a ‘trustworthy’ individual. Betrayal can be seen as an indication of weakness and inconstancy.

It’s because of these harms that we have so many damning terms for betrayers: fair-weather friends, turncoats, traitors, snitches, sneaks, weasels, rats … And it’s because of these harms that we often figure loyalty is a good thing.

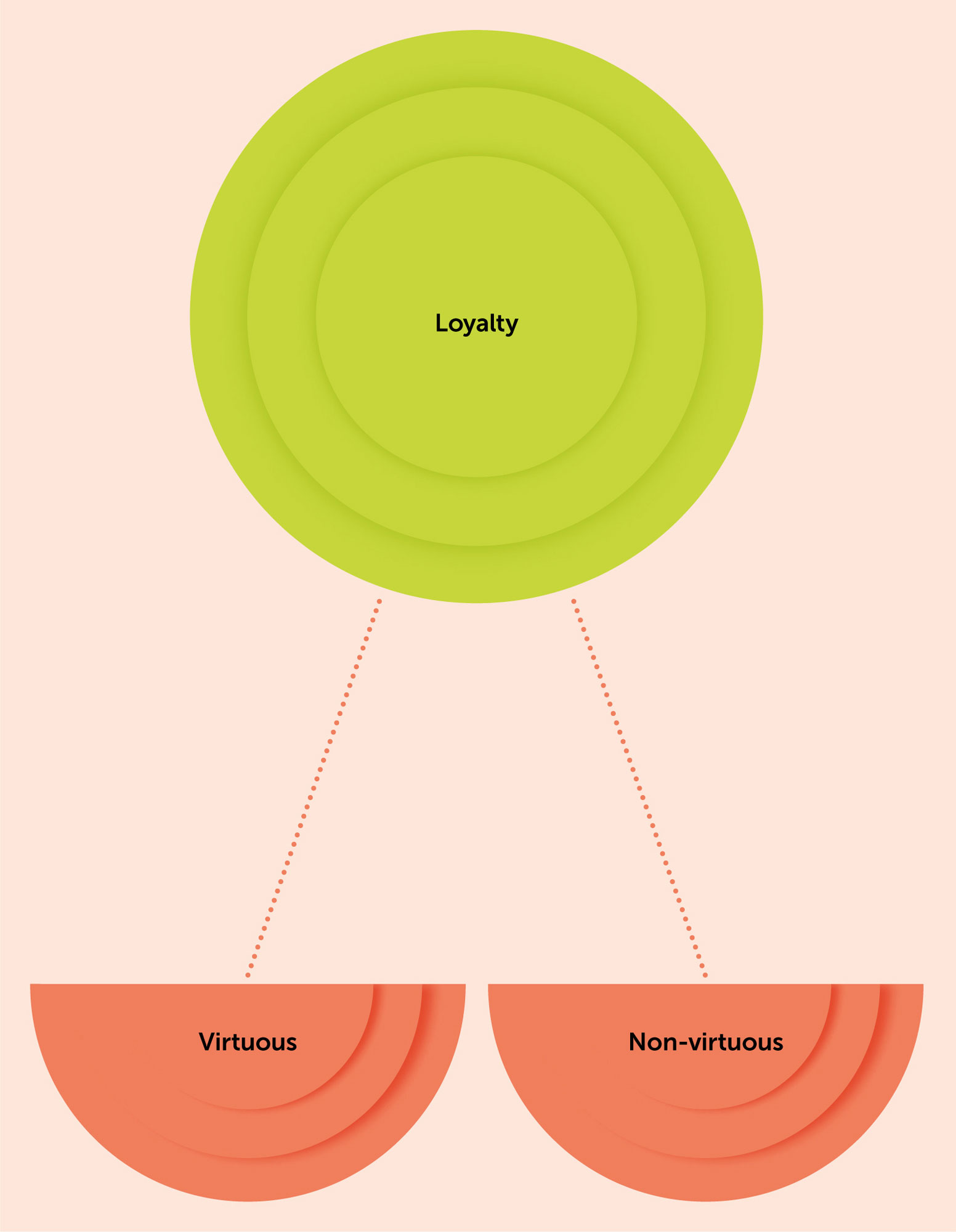

The 19th-century American philosopher Josiah Royce wrote in his book, The Philosophy of Loyalty (1908), that loyalty is ‘the willing and practical and thorough-going devotion of a person to a cause’. We can be loyal to ideals and institutions. More recently, the moral philosopher, Marcia Brown, has pointed out that we more typically take ‘loyalty’ to refer to a relationship between persons. You can be loyal to your partner if, despite being attracted to someone else, you nevertheless remain faithful. You can be loyal to your friend if, despite pressure to sell them out, you keep schtum. We tend to prize these kinds of actions and typically label loyalty as ‘a virtue’.

Loyalty offers security. If you’re the nervous type, your partner’s loyalty will offer considerable comfort. And loyalty is good for both you and the recipient. If you’re loyal to something (a football club, for example), your relationship to that thing is enhanced. You identify with the institution or person or principle that you’re loyal to. If I’m loyal to my family, and put the needs of my family before my own, it’s because, in a way, I see my own needs as inextricably tied up with theirs.

Loyalty, then, seems to be a good thing. But seeming is different from being. Is loyalty so certain a virtue?

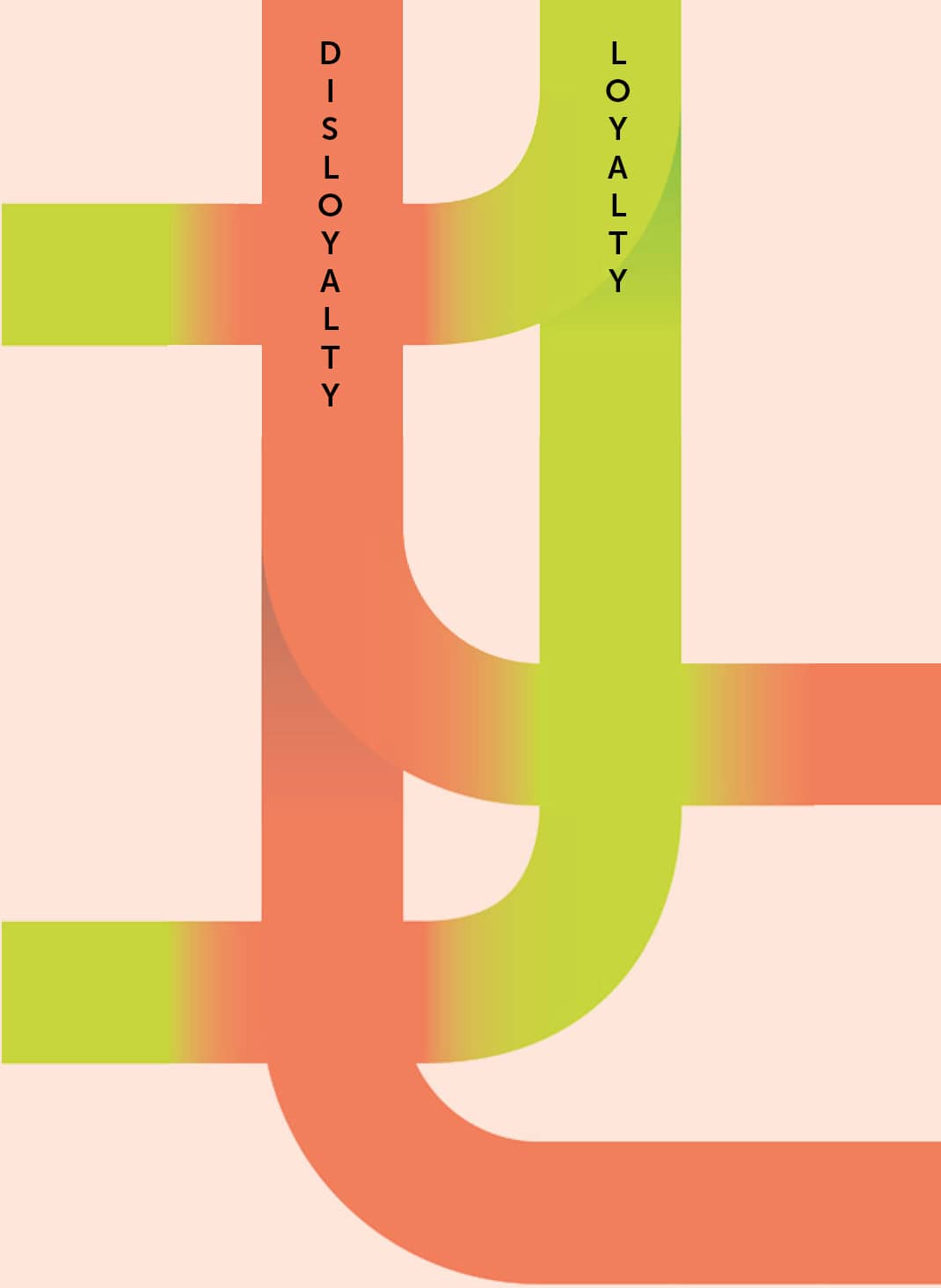

THE VALUES OF DISLOYALTY

‘Loyalty confines you to accepted opinions; loyalty forbids you to comprehend sympathetically your dissident fellows…’ Graham Greene

‘The first thing I want to teach is disloyalty till they get used to disusing that word loyalty as representing a virtue. This will beget independence…’ Mark Twain

There are, as these quotations attest, a few folk who are slightly more circumspect about the so-called virtue of loyalty. The general thought, articulated by the novelists Twain and Greene, is that loyalty is restrictive. It undermines your independence. It’s a form of control. The examples discussed above show us its positive effects, but there are plenty of cases where it can have slightly more dubious results.

Consider Akosua. She has been working hard at her job for a couple of years and has swiftly risen to managerial level. Perhaps she has been helped in some minimal way by one of the partners in the firm: a kindly old soul called John. One day Akosua discovers that John has been paying for fancy dinners with the company credit card. It’s wrong, and she knows it. So should she report him? The Johns of this world typically rely on a ‘sense of loyalty’ to keep people less powerful than themselves quiet. Would disloyalty in this situation really be a bad thing?

It’s easy to imagine even more troubling cases where people in power use loyalty to silence their employees and co-workers.

As Marcia Baron points out in The Moral Status of Loyalty (1984), there are numerous instances of disloyalty having beneficial effects and undermining objectionable institutions. Remember, it’s the concept of loyalty – to one’s queen, or lord – which supported the hugely unequal feudal society. And it’s disloyalty, or ‘whistle blowing’, that means that otherwise well-protected industries that benefit from, for example, slave labour, can be brought to justice. Disloyalty to presidents, queens and company bosses can bring to light hidden abuses of power.

Loyalty, says Baron, can stand as an obstacle to justice. It’s a dissuasive force that encourages you to leave certain things unquestioned. This thoroughgoing commitment to a person or cause overrides your ability to critique the objects of your loyalty effectively. The consequences of such loyalty can be horrendous. Take, for example, the German soldiers who were unthinkingly loyal to the Third Reich, or the British citizens who gave unswerving loyalty to the empire and its exploitative colonial activities.

Sure, loyalty can prevent you from doing bad things. It can stop you from cheating on your partner. But loyalty also protects others when they do bad things. It allows businesses to continue in their dodgy dealings, and leaves individuals open to exploitation. The effects of loyalty can be both positive and negative – and, interestingly, the same is true for disloyalty. So if loyalty’s a virtue, maybe disloyalty can be one too?

TOOLKIT

TOOLKIT

01

Much of the time we argue competitively – as though we can win or lose – but there are distinct advantages to arguing collaboratively. Two heads are better than one.

Thinking point Do you think more carefully if you’re arguing to win?

02

When you lie to someone you take away their ability to reason – so, according to Kant, you should always tell the truth (even when faced with an axe-wielding criminal).

Thinking point If reason is what matters, is it okay to lie to someone with a severe mental impairment?

03

Respect can mean either admiration or acknowledgement of human dignity. The latter means seeing someone as responsive to reasons.

Thinking point When was the last time a bigot changed your mind?

04

Loyalty can enhance your relationships with other people (and football clubs), but sometimes disloyalty can be very valuable in exposing exploitative systems.

Thinking point Are there ever cases where loyalty is more important than justice?

FURTHER LEARNING

FURTHER LEARNING

READ

Two Kinds of Respect

Stephen Darwall, Ethics (1977)

Loving Your Enemies

Martin Luther King Jr, (1957) www.kingencyclopedia.stanford.edu/encyclopedia/documentsentry/doc_loving_your_enemies.1.html

Relativism, Persons, and Practices

Amelie Rorty, in Relativism: A Contemporary Anthology (Colombia University Press, 2010)

LISTEN

‘Political Distrust’ (Episode 13), The UnMute Podcast

Presented by Myisha Cherry with Meena Krishnamurthy. You should listen to the UnMute Podcast right now! It’s full to bursting with fascinating discussions – all hosted by the excellent Myisha Cherry.

WATCH

Beau Travail

Directed by Claire Denis, this stunning and disturbing film about life in the French Foreign Legion demonstrates some of the complex ways in which lies, respect and loyalty intersect.

Fargo

A strange and blackly comic television series, FX’s Fargo examines the lies and betrayals that result after an insurance salesman, Lester Nygaard, commits murder.

Wi-Phi

‘Wireless Philosophy’ is a fantastic, free online resource of short videos covering a range of political and philosophical topics

VISIT

How the Light Gets In

The annual Hay-On-Wye philosophy and music festival brings together philosophers, politicians, novelists and musicians to discuss anything from angst to Zeno’s paradoxes. Definitely worth popping along.