LIFESTYLE

LESSONS

05 MARRIAGE

What better way to celebrate your love than by getting married? Well, maybe by not getting married.

06 MAKING BABIES

People seem to like making babies – but is there a moral imperative to adopt or foster pre-existing children?

07 EATING MEAT

Vegetarianism looks like an ethical response to the horrors of the meat industry, but isn’t veganism better? How do we meet all these moral concerns?

08 SHOPPING

‘Commodity fetishism’ isn’t a sex thing – it’s a powerful concept for explaining our attitudes to all the junk that we’re tempted to buy.

‘Life is more than earning a living, and if you’re not in the habit of thinking about it, you can end up middle-aged or even older and shocked to realize that your life seems empty.’

Martha C. Nussbaum

Every so often we’re faced with big life decisions: should I get married? Should I have a baby? Should I eat meat? And the smaller ones: should I buy that brand-new pair of sneakers even though my old ones are barely worn? Our answers to these questions constitute our style of living – or, more pithily, our ‘lifestyle’. This is the focus of the present chapter.

Much of the time, if we’re thinking about marriage or making babies, the question is not whether but when. Should I marry this person now? Am I at a stage in my life when I can look after a bawling infant? The aim in this chapter is to look at the ‘whether’ questions: whether I should get married at all; whether I should have a baby (and if so, how?) We’re also going to look at more routine activities. Most people eat meat and go shopping on a daily basis; what are the ethical quandaries these situations provoke? If we don’t eat meat, what can we eat? And are ‘commodities’ really as straightforward as they first appear?

One thing that will become clear over the following pages is that all these questions are interlinked. Being a vegetarian isn’t just about what food you put in your mouth; it’s about what clothes you buy and who you vote for. Likewise, the decision to have a baby may have just as many environmental consequences as factory farming. This thought, that there are no discrete areas of ethical concern, is found in the work of philosophers from Aristotle to Patricia Hill Collins. It’s one to keep in mind as we go through the following lessons.

MARRIAGE

There are countless reasons to get married. You and your partner are head-over- heels in love. You want to announce your commitment to each other by enacting one of the oldest love rituals in human history. You also like tax breaks – just one of the many practical benefits enjoyed by married couples. Other benefits include improved social standing and certain legal rights (relating to inheritances and hospital visits). Visas are another reason to get married. And if those weren’t enough, think of the snazzy dresses and blowout parties.

Collectively these reasons might seem persuasive, but what about individually? Imagine you ask a bride-to-be why she’s getting married and she answers, ‘Because of the tax-breaks.’ Her husband-in-waiting adds: ‘And my visa.’ Huh? Neither response seems to be in ‘the spirit’ of marriage – this ancient institution is being seen as a way of attaining practical benefits. If you ask someone why they’re eating an apple and they say, ‘Because it’s low in calories,’ they might as well eat a rice-cake. If they say ‘Because I love the appley taste!’ you can only say, ‘Fair enough’.

Philosophers often separate things into intrinsic goods, i.e. ones that are essential to an activity, and extrinsic goods, which are not. Tax breaks, visas, parties, rings and party rings are extrinsic goods – and while they might constitute reasons to get married, they might also constitute reasons to, for example, enter into a civil partnership. They’re ‘add-ons’.

The Cambridge philosopher Clare Chambers suggests that marriage is an institution that people enter into largely because of the meanings it represents. Add-ons aside, there’s something about marriage itself that’s seen to be valuable. In her essay, ‘The Marriage-Free State’ (2003), she writes:

‘Couples may marry so as to obtain various practical benefits, but a key aspect of most marriages is the statement the couples make about their relationship. For the marrying couple and for society in general, the symbolic significance of marriage is at least as important as its practical aspects … This being the case, it is impossible to escape the history of the institution. Its status as a tradition ties its current meaning to its past.’

So some folk think marriage is valuable in and of itself – because of what it means – and, as Chambers indicates, its meaning is a function of the historical, cultural processes that produced the tradition. The wedding ceremony is one example of the way in which marriage can provide a rich vocabulary – of symbolic gestures and rites – with which a couple can declare their mutual love and commitment, in front of society and (depending on their religious inclinations) in front of God. These things are intrinsic to the ancient tradition.

That all seems fine … until we start looking at this history more closely. What are we really buying into when we say ‘I do’?

BUILDING NEW TRADITIONS

In her essay, Clare Chambers describes marriage’s troubling past. It figures, unfortunately, as an institution that has given rise to numerous human rights violations – most obviously, against women. Philosophers and historians, from Simone de Beauvoir to Ralph Wedgewood, have described how, from its earliest days, marriage has construed women as commodities to be exchanged. Brides are seen as bargaining chips, used to secure advantageous links between families – and of course, for the production of heirs.

We may, of course, think the institution no longer functions in this way. Same-sex marriage is now widely, if not universally, recognized. Women can even keep their names if they like! Sure, the response goes, the whole thing used to be rather suspect, but institutions can change. Once upon a time, Western democracy denied women the right to vote. It’s different now. Can’t the same be true for marriage?

Chamber’s central point is that most people see marriage as valuable because of its symbolic significance (rather than the add-ons). They’re interested in its status as a tradition – and this, interestingly, pushes its problematic past to the fore. It’s not something that can be ignored.

Think of the symbolism that runs throughout the wedding ceremony. The father-of-the-bride ‘gives away’ his daughter. But in the normal course of things, we only give away things we own and we don’t tend to own people. The officiating priest tells the groom he ‘may now kiss the bride’. But the bride’s wishes are not considered – she’s given no opportunity to decline.

What about the white dress, which is supposed to symbolize the bride’s virginity? Women, says the dress, should not have sex before marriage. That seems ill-advised, not to say unfair – especially since the same rule is not applied to men. And think about the traditional exclusion of same-sex couples, which is closely woven into the heterosexist fabric of the wedding rites.

When people marry because they value the tradition, it appears to follow that they value these troubling symbolic associations. This is why philosophers like Clare Chambers and Elizabeth Brake suggest we should reassess our attitude towards marriage. As the title of her essay indicates, Chambers advocates a ‘marriage-free state’. By constructing new legal arrangements, we can, she says, get the benefits of the add-ons (parties, taxbreaks, etc) without any of the symbolic violence. Brake’s position is slightly different. In her book, Minimalizing Marriage (2011), she encourages us to retain the term ‘marriage’ but to use it subversively to apply to all legal-bound, caring adult relationships.

Marriage is an old and well-recognized institution. As a tradition, it’s popular and pervasive. The questions Chambers and Brake encourage us to ask ourselves are, should it be? And what could we put in its place?

MAKING BABIES

There’s no denying it: with their squishy faces and tiny hands, babies can be pretty adorable. Sure, they have downsides – they can’t talk, or use toilets and are prone to vomiting – but on the whole, we like them. In fact, a lot of people like them so much, they try and make their own.

It’s not hard to see why humans are such big fans of procreation. For one thing, we’ve been doing it since … well, forever. Since the Year Dot. It can be the product of a famously pleasurable pastime – and it’s sort of expected, isn’t it? Like dying, creating your own child is seen to be an inevitable part of human life. Find a partner, make a baby. That’s just how it goes. Plus they’re cute. Did I mention that already?

People love babies – and philosophers, unsurprisingly, love to talk about them.

Take, for instance, the superbly titled B.U.M.P. project (Better Understanding the Metaphysics of Pregnancy) at the University of Southampton. Set up in 2016, Elselijn Kingma’s research group looks at the metaphysical puzzles that pregnancy creates. Is a foetus a part of its mother? What about an egg? At what point do these things become distinct entities? At what point does the baby actually come into existence?

There’s also the epistemological angle. What puzzles do pregnancy and procreation raise for the production of knowledge? In her fascinating paper ‘Mother Knows Best’, Fiona Woollard persuasively suggests that women who have experienced pregnancy have a privileged sort of knowledge that others lack. Woollard says that the phenomenology of the event is special. There’s no other phenomenon quite like ‘the mystery of living with two heartbeats knocking out their rhythms’ (as Chitra Ramaswamy puts it in her book Expecting, 2016). Pregnancy is a mind-expanding experience.

The epistemology of pregnancy also leads us into the sphere of ethics. A central claim in Woollard’s essay is that, by virtue of their unique perspective, mothers have a particular contribution to make to political debates about pregnancy. There’s something relevant that these women know, which other people don’t, that bears on how abortion is debated. If you don’t know what it’s like to be pregnant, how can you ask someone to remain pregnant against their will? How can men have informed opinions about such things?

Mothers are giving birth all around us, all the time – around 353,000 every single day – and it’s easy, perhaps, to forget how wonderful and fascinating this actually is. You’re somewhere, reading this, and POP, there’s another baby, and POP there’s another one, and POP another – and isn’t that incredible? And a little bit overwhelming?

EXISTENCE PROBLEMS

Babies are cute, and pregnancy is obviously philosophically intriguing. But are there any ethical puzzles about the biological creation of an infant? Philosophers Tina Rulli and David Benatar, and Queer theorist Lee Edelman, would answer that there are.

In his book No Future (2004), Edelman suggests that the reasons we typically give for procreating usually have little to do with the baby itself. Consider why you might want to create your own child. Well, you may say, babies are adorable. Plus, having a son or daughter can give your life meaning. It changes your perspective on the world. Having a baby is also a profound expression of love for your partner (you love them so much you want your DNA to meld together!) All well and good, but these reasons configure the baby instrumentally. That is, this imagined baby is seen as a means to an end – be it the enhancement of your life, or your partner’s or of society in general.

When we think about having babies, we can’t help but think of them in instrumental terms. Why? Because they don’t exist (we’ll talk more about existence in Chapter 3). Their hopes and desires can’t figure in our decision to procreate because nonexistent things don’t have hopes and desires. Imagine prospective parents telling you what their future baby will want from life – to be a doctor, say. That would feel odd, because there’s nothing to which the desires can be ascribed! It’s not surprising, then, that when it comes to procreation, the focus shifts onto the hopes and desires of existent things (like ourselves).

Tina Rulli, a philosopher at the University of California, encourages us to spend more time thinking about existing children. In her article ‘The Ethics of Procreation and Adoption’ (2016), she points out that there are kids up for adoption or fostering, whose lives would be immeasurably improved by having the stable home you’re thinking of providing for your as-yet-nonexistent offspring. There is, she proposes, a relatively uncontroversial moral obligation to look after people who are already suffering rather than to create new people for you to invest these energies in. It’s not rocket science: if you’ve got a sad baby and can help it, why would you focus on creating a completely new baby?

There are obviously more dimensions to this discussion, but the question raised is an important one. Why would you biologically create your own child rather than foster or adopt? Is it because you want a baby that looks like you? Is it because you’re naturally inclined to procreate? Are you worried that foster kids are somehow ‘damaged’? Do any of these reasons really trump Rulli’s moral principle that it’s better to care for the living than create a new recipient for your love?

EATING MEAT

In the 1970s, the Australian moral philosopher Peter Singer wrote a book called Animal Liberation: A New Ethics for Our Treatment of Animals (1975). It quickly became one of the most well-known and influential philosophical texts of the 20th century. One of the reasons for this was an argument Singer includes about hamburgers.

Okay, fine, the argument isn’t just about hamburgers – it’s about a bunch of other tasty foodstuffs too. Chicken nuggets. Roast duck, veal and caviar. Beef, meat loaf and bacon. It’s an argument that says we should stop eating them.

Singer takes his philosophical lead from the 18th-century social reformer, Jeremy Bentham – one of the founders of the philosophical movement known as utilitarianism. The central utilitarian principle, which Singer commends, is that we should do whatever causes the greatest good and minimizes the most suffering. That’s a fairly straightforward rule of thumb, isn’t it? Suffering is wrong – and minimizing it seems like a good idea.

Singer’s main innovation was to couple this moral principle with a critique of something called ‘speciesism’ – the prejudice displayed by certain species (mentioning no names, Homo sapiens…) against beings of other species. It’s not hard to be impressed, like Singer, by the idea prevalent in Algonquin and Iñupiaq culture, that humans are part of a continuum in nature just as much as other animals. There’s no real reason, says Singer, for us to think of ourselves as having any particular privileges because of the species to which we belong. And this applies in the moral sphere as much as any other.

His thought, then, is that nonhuman animals shouldn’t be treated like ‘wind-up clocks’ (despite what the Cartesians say). They feel pain, they feel pleasure. They can suffer. And their capacity for suffering is morally relevant. When we’re doing our utilitarian equations, totting up the good and bad, we need to factor in the suffering of cows and sheep and all the other creatures we serve for dinner.

‘The question’, as Bentham himself put it, ‘is not, “Can they reason? Can they talk?” but, “Can they suffer?”’ The answer, Singer thinks, is an emphatic YES. And it’s difficult to disagree. Many of us have seen those gut-churning documentaries about how hamburgers are made. How fish are farmed. The horrible living conditions of battery chickens. The butchering of cattle. Of course, we derive a certain amount of pleasure from eating meat – but it isn’t, Singer thinks, nearly enough to weigh the balance in favour of the brutalizing of nonhuman animals.

There are points for and against Singer’s position, and as he points out himself, his argument has been considerably less effective than he’d hoped (just look at the continued expansion of the fast-food industry). Still, there remains something profoundly powerful about the ideas fleshed out in Animal Liberation – and something disturbing about how easily we exclude beings of other species from our moral calculations.

HOW COME YOU’RE NOT A VEGAN?

One question vegetarians routinely get asked is, How come you’re not a vegan? – which is, it must be said, a rather irritating thing to ask. Unfortunately, like a lot of irritating things, it’s also quite important. The utilitarian principle seen to motivate vegetarianism also goes beyond it.

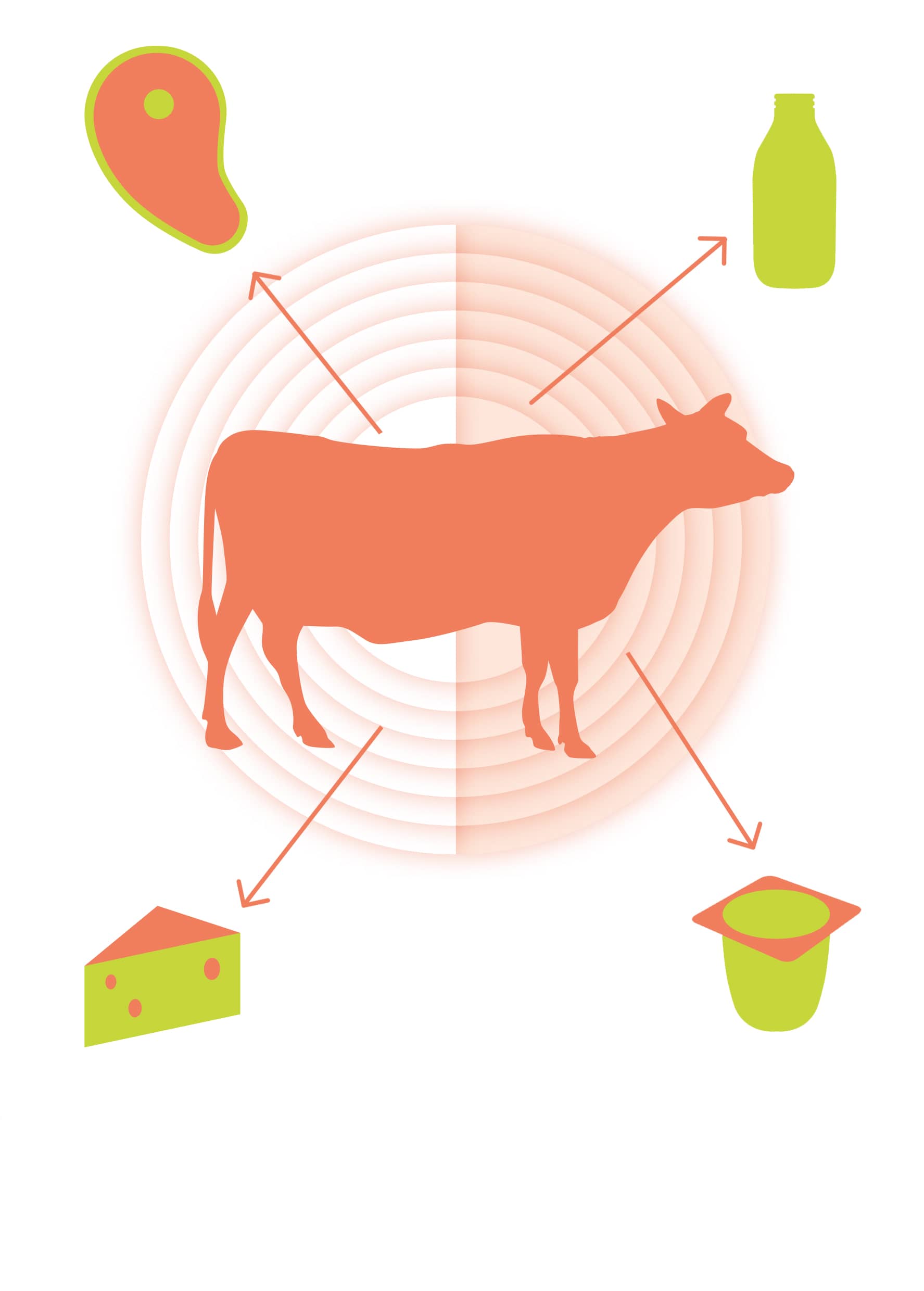

The dairy industry is – by Singer’s reasoning – almost as bad as the meat industry. For instance, cows only produce milk once they’ve given birth, so they have to have babies once a year to keep lactating. Once a year! Can you imagine? Furthermore, all of the male calves are killed and (at best) ground down into mincemeat (and at worst … well, it’s better not to ask). If I want to minimize animal suffering, I have to stop drinking milk and eating cheese and yoghurt as well.

And the problems don’t stop there. Veganism brings its own issues. Vegans need protein – and with cheese and meat off the menu, they’ll turn to nuts to get their recommended daily allowance. But the nut industry is susceptible to just as many problems as the meat and milk industries. Take almonds: they require a huge amount of water to grow, and extensive water re-direction can (and does) lead to widespread drought in almond-growing communities. On top of that, not all countries have the climate for nut-growing, so supermarkets have to ship them in – and, guess what? The fumes from boats and planes are contributing to global warming.

When you’ve got too much on your ethical plate, it’s good to remember a lesson learned from Onora O’Neill: ought implies can. We want to be good people. We have moral codes and these codes tell us what things we ought to do. But the suggestion that we ought to stop harming animals only makes sense if it’s possible for us to stop harming animals. We can’t be expected to do things that it’s not possible for us to do.

Given how most of us live, given the kinds of shop-bought things we wear and eat and use, it’s difficult (if not impossible) to be sure whether animal suffering has been a by-product of their manufacture. It would be a full-time job mapping out the causal chain that resulted in the making of this sandwich, or that chocolate bar – it’s just not practically possible.

This doesn’t, however, mean that we should just give up. The wonderful Ruth Barcan Marcus, in an essay titled ‘Moral Dilemmas and Consistency’ (1980), describes a ‘second order regulative principle’. Roughly speaking, this principle holds that instead of trying, impossibly, to meet all these various moral demands (which will result in moral burn-out, if not outright conflict), we have a responsibility to get ourselves into a position where it’s possible to address these concerns. You don’t want to be the cause of needless animal suffering, but you only have finite resources to prevent this from happening. You should invest these resources wisely, she says. You should use practical judgement so that your moral practice can become sustainable.

Living a moral life isn’t simply a matter of deciding which things you should and shouldn’t do. It’s a matter of building a lifestyle around these aims. Not all of them will be immediately achievable. You may think it’s better to be a vegan than a vegetarian, but it may well take some time researching delicious oat-based milk substitutes before you can finally fulfil this ambition.

SHOPPING

‘A commodity appears, at first sight, a very trivial thing, and easily understood. Its analysis shows that it is, in reality, a very queer thing, abounding in metaphysical subtleties and theological niceties.’

That’s Marx. Karl, not Groucho. He’s talking about iPads and sofas and frisbees and novelty hats and those tiny figurines you get in Kinder Eggs and the Kinder Eggs too. He’s talking about commodities – those everyday items we put in our houses our cars and our places of work – all commodities.

Marx, the 19th-century Prussian-born philosopher and economist, spent a huge amount of time thinking about these ostensibly ordinary objects. The quote above comes from the first chapter of his magnum opus, Capital: Critique of Political Economy (1867), in which he describes the economic models underpinning what he saw as ‘capitalist’ society. It’s a hefty tome, jam-packed with novel thoughts – but for present purposes, we’re just going to look at his view of these supposedly ‘trivial’ things.

A commodity, roughly speaking, is something you can buy, which has been produced by human labour. That’s pretty vague, isn’t it? It includes cups and saucers, but also computer programs, and more abstract things, like an hour with a management consultant or a package holiday to the Maldives.

Commodities, according to Marx, have two distinct properties. On the one hand, they have ‘use value’. The use value of something like a wooden spoon relates to what you can do with it (use it for stirring, say). They also have ‘exchange value’. What can you exchange a spoon for? In ye olde days, we might have exchanged a well-carved spoon for a duck or a brace of turnips. Nowadays, we’re more likely to exchange it for an hour or two’s hard graft in the office through the medium of money. You get paid a certain amount for your labour and you use the money you earn to buy a beautiful spoon.

For Marx, the focus in a capitalist economy is very much on the latter of these two values. Capitalists aren’t especially interested in what the object is or how it can be used, but in what you can exchange it for and whether or not it will make a profit. The market is geared to that end, the production of profit rather than the production of useful items … which is probably why there’s so much stuff around the place.

BEHIND THE CURTAIN

Lke all good magical items, commodities appear out of nowhere. Most of the time, we see them on the shelves, as though they’ve just popped into existence. Sure, we’re aware people stock the shops, but our thoughts rarely go beyond that. In the normal run of things, we have absolutely no contact with a commodity’s producers. We don’t see them and we certainly don’t exchange things with them directly. Long gone are the good old days of turnips and wooden spoons. Indeed, a lot of the time, each commodity (your digital watch, say) is produced by a huge number of people, and these producers themselves rarely see, let alone speak to each other either.

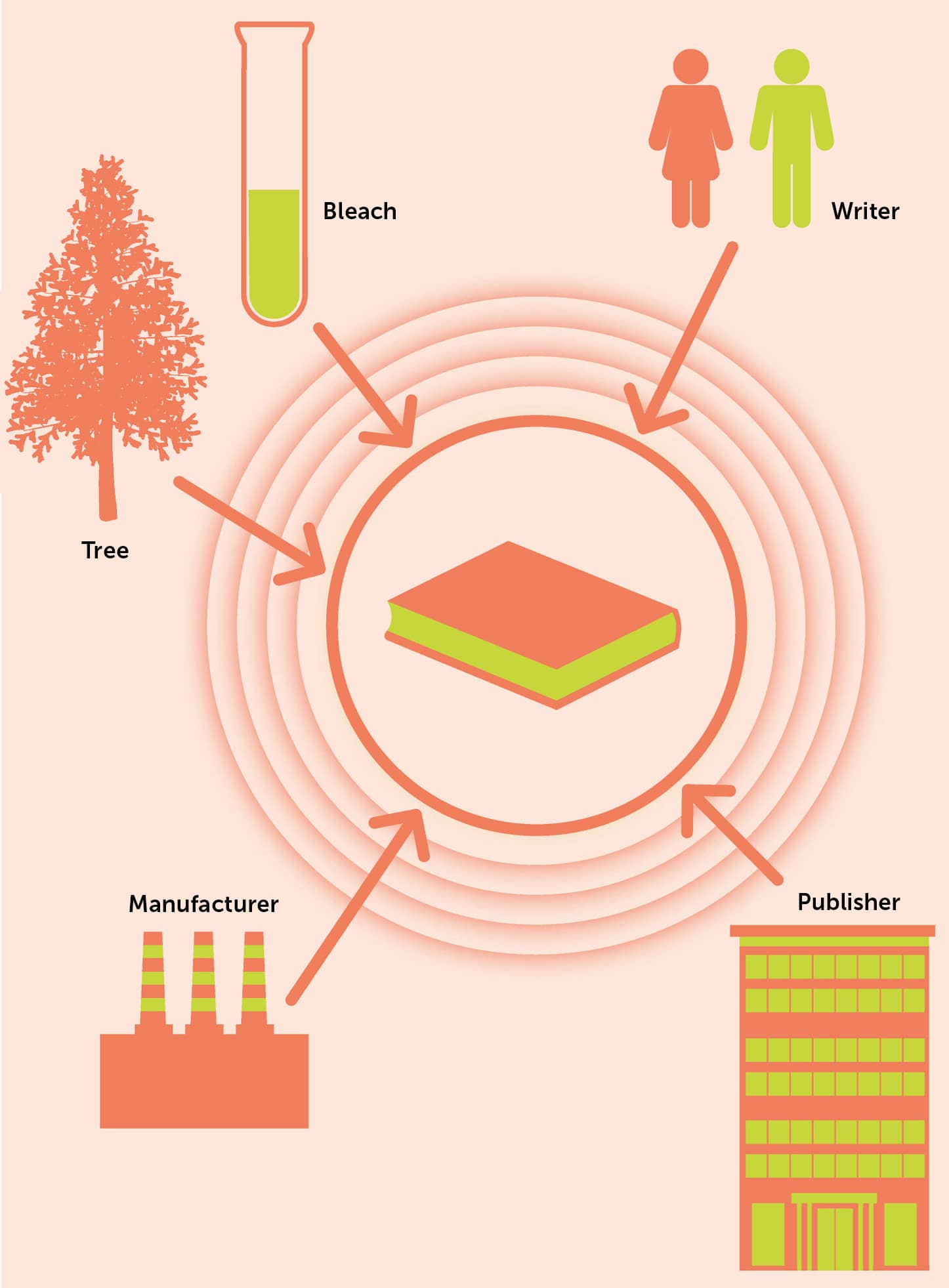

Think of all the various materials that have gone into making this book. The paper, for one thing. The bleach that’s turned the paper white, the glue that’s glued the spine. The ink, the plastic, or the laminate that gives it a glossy shine. All of these have different origins and yet we engage with the book as a single, unified object. In actual fact, it’s designed to look like that. The manufacturers have taken incredible care to erase the signs of its production.

We don’t think of books as being produced by people. As you’re reading this, you’re unlikely to be thinking of the hours I’ve spent sitting at my desk typing out these words, or about how much I’m getting paid. It’s unlikely you’ve thought at all about the working conditions of the designers, the editors, the printers and publishers. Or the foresters who grow the trees that make the paper, or the chemists who’ve made the pigment to make the ink. These aspects of the book are well and truly hidden – and that’s the magic of commodities. We don’t see them as the products of human labour. We don’t think about the people who made them or about how these people are treated.

At the end of the day, ‘commodity fetishism’ is not a particularly impressive type of magic. It’s like David Copperfield; the producers haven’t actually disappeared – it’s a trick of the light. The often exploitative social relations are still there. In Marx’s book Capital (1867), he was trying to pull back the curtain to show how we’re being duped. The next time you go out to buy something, try and think about its use value, its exchange value and the producers that made it happen.

TOOLKIT

TOOLKIT

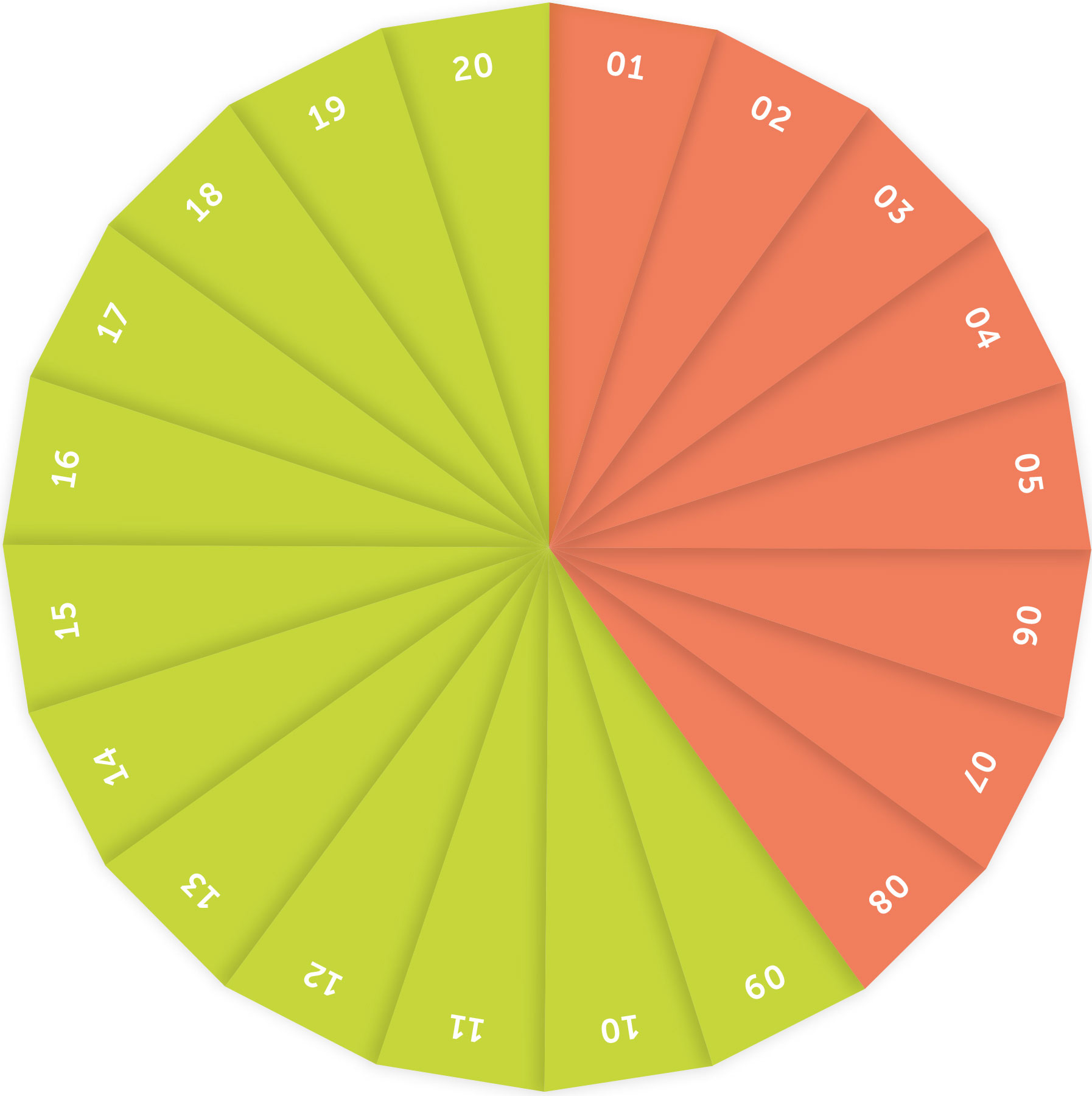

05

The institution of marriage has a disturbing history. If we celebrate it as a tradition then it’s hard not to celebrate its troubling past.

Thinking point Are there any traditions that don’t have a troubling past?

06

Having children is a wonderful, mind-expanding experience, but there might be a moral imperative to look after existing children rather than create new ones.

Thinking point Does this mean humans should stop having babies?

07

Animal suffering motivates us to change what we eat. To avoid becoming overwhelmed by ethical demands, we need to recognize our limited personal resources and deploy them sensibly.

Thinking point Can there ever be good reasons to stop yourself caring about injustice?

08

By fixating on the commodity rather than on the means by which it is produced, we tend to forget that many of our everyday purchases are the result of exploitative labour.

Thinking point What do you need to do in order to buy better?

FURTHER LEARNING

FURTHER LEARNING

READ

We Are What We Eat

Cathryn Bailey, Hypatia (2007)

If You’re an Egalitarian How Come You’re So Rich?

G.A. Cohen (Harvard University Press, 1996)

Exploitation

Nancy Holmstrom, Canadian Journal of Philosophy (1977)

LISTEN

‘The Morality of Parental Rights’, The Moral Maze

BBC Radio 4 debate presented by Michael Buerk with Ed Condon, Raanan Gillon, Carol Iddon and Dominic Wilkinson. The Moral Maze is one of the BBC’s political debate programmes that often features interesting contributions from philosophers.

WATCH

The Spectre of Marxism

Academic and broadcaster Stuart Hall explores Karl Marx and the history of Marxism in this in-depth BBC documentary from 1983.

Carnage

A fascinating (and often hilarious) fusion of fact and fiction, this docudrama directed by Simon Amstell discusses the impact of meat- eating in the 21st (and 22nd) centuries.

VISIT

Phil.Cologne

In 2017, over 12,000 people attended the fifth Phil.Cologne festival in Cologne, which speaks to the growing popularity of philosophical discussion in Germany. The organizers do a good job of getting a range of philosophical opinions.

Festival of Questions

Part of the famous Melbourne Festival, the Festival of Questions gathers together politicians, philosophers and comedians to discuss (sometimes provocatively) important issues facing 21st-century Australians.