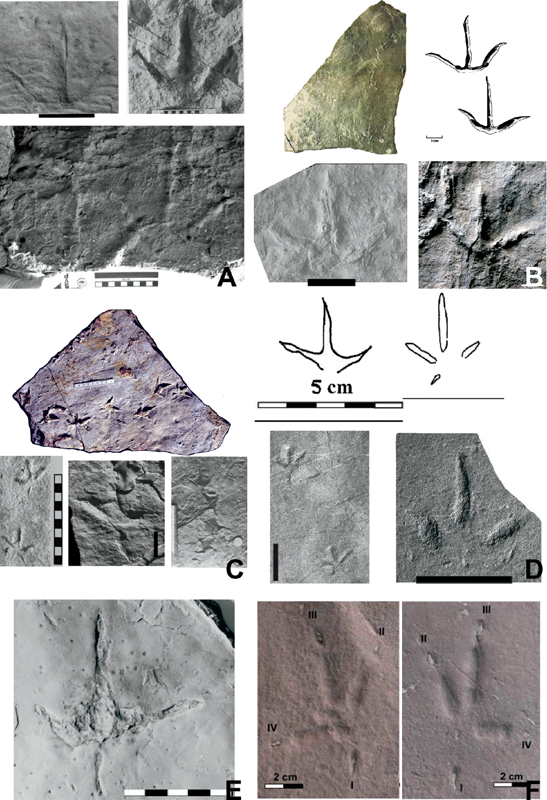

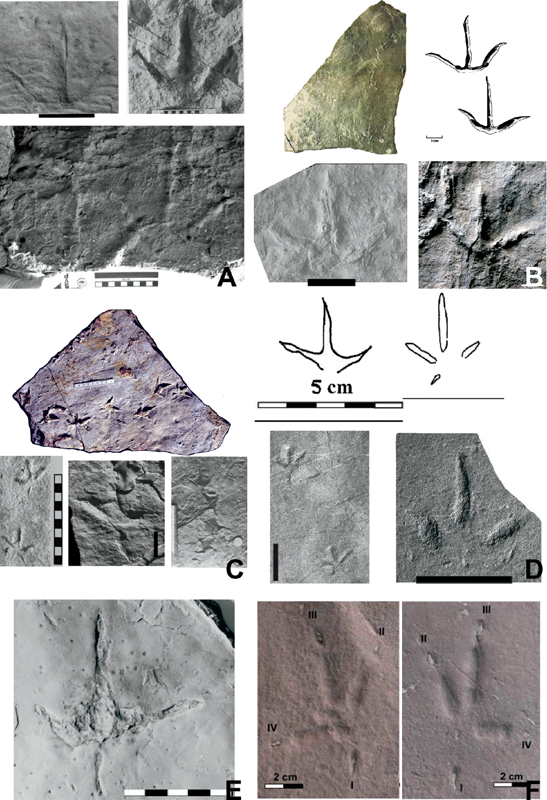

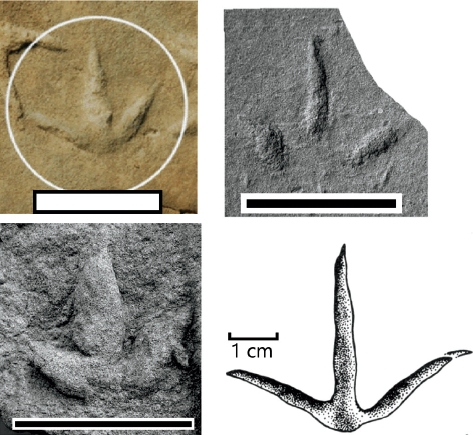

15.1. Ichnofamilies considered in this study. (A) Magnoavipes, a previously contentious ichnogenus originally described as the trace of a large avian but now considered to be that of a nonavian theropod (Matsukawa et al., 2014). (B) Avipedidae and Limiavipedidae: (upper left) Avipeda (modified from Vialov, 1965); (upper right) Aquatilavipes swiboldae, scale = 1.0 cm (modified from Currie, 1981); (lower right) Aquatilavipes izumiensis, scale = 1.0 cm (modified from Azuma et al., 2002); (lower left) Limiavipes curriei, scale = 5.0 cm (reassigned from Aquatilavipes curriei, McCrea and Sarjeant, 2001; McCrea et al., 2014). L. curriei is much larger than any Mesozoic ichnospecies of Aquatilavipes. (C) Ignotornidae: (top) Ignotornis mcconnelli, holotype (Lockley et al., 2009); (lower left) Goseongornipes markjonesi (Lockley, Houck, et al., 2006); (bottom center) Ignotornis yangi (Kim et al., 2006); (lower right) Hwangsanipes choughi (Yang et al., 1995). Scale divisions in centimeters. (D) Koreanaornipodidae: (top) Koreanaornis hamanensis (Kim, 1969); (lower left) Pullornipes aureus (Lockley, Matsukawa, et al., 2006); (lower right) Koreanaornis dodsoni (Xing et al., 2011). Scale bar = 5.0 cm. (E) Jindongornipodidae. Jindongornipes kimi (Lockley and Rainforth, 2002). Scale = 5.0 cm. (F) Shandongornipodidae. Shandongornipes muxiai (Lockley et al., 2007): (left) left track LRH-DZ70 and (right) right track LRH-DZ67 (from the Qingdao Institute of Marine Geology). Both tracks from S. muxiai holotype trackway LRH-DH01. Scale = 2.0 cm.

Analyzing and Resolving Cretaceous Avian Ichnotaxonomy Using Multivariate Statistical Analyses: Approaches and Results |

15 |

Lisa G. Buckley, Richard T. McCrea, and Martin G. Lockley

SEVERAL NEW ICHNOTAXA OF AVIAN TRACKS HAVE BEEN described in recent years, adding to the known ichnodiversity of Cretaceous avians. The naming of new avian ichnospecies and ichnogenera has resulted in the creation of several avian ichnofamilies, but due to the challenges of documenting bird tracks, there are several ichnogenera that to date remain unassigned to any ichnofamily. Multivariate statistical analyses can be used to quantitatively test avian ichnotaxonomic assignments. Ichnospecies within the ichnofamilies Avipedidae (Aquatilavipes swiboldae, A. izumiensis, and A. curriei), Ignotornidae (Ignotornis mcconnelli, I. yangi, I. gajinensis, Hwangsanipes choughi, Goseongornipes ichnosp., G. markjonesi), Koreanaornipodidae (Koreanaornis hamanensis, K. dodsoni, Pullornipes aureus), Shandongornipodidae (Shandongornipes muxiai), and Jindongornipodidae (Jindongornipes kimi), were analyzed. Also included are the ichnotaxa Magnoavipes (M. lowei, M. caneeri, M. denaliensis), Uhangrichnus chuni, Dongyangornipes sinensis, Morguiornipes robusta, Barrosopus slobodai, and Tatarornipes chabuensis, and data from 59 tracks of small theropods from the Early Cretaceous of western Canada.

The results show strong statistical support for all described ichnogenera and ichnofamilies. The ichnogenus Magnoavipes does not group with any other avian ichnotaxon in this analysis, suggesting that interpretations of a nonavian affinity for the ichnogenus are accurate. Also, several unassigned ichnogenera occupy the same morphospaces as those of described ichnofamilies. However, the statistically well-differentiated ichnofamilies Koreanaornipodidae and Avipedidae occupy a similar morphospace despite large morphologic differences. The data also show that both avian and theropod tracks have overlapping morphologies that make a 100% separation improbable. Total digit divarication is a reliable discriminatory value only on a population level. Trackway data (pace and stride lengths, track rotation, pace angulation) provide the most accurate data in separating bird trackways from those of theropods.

Multivariate statistical analyses have the potential to both test ichnotaxonomic assignments and show morphospace groupings that reveal previously undocumented patterns. However, a multivariate data set is only as strong as the most incomplete data table and is not immune to a priori assumptions regarding ichnotaxonomic assignment, data collection techniques, and/or preservational condition of the specimens in question. Increasing the number of measured parameters when reporting new avian ichnotaxa will serve to strengthen the utility of multivariate analyses in vertebrate ichnology.

INTRODUCTION

Avian track types (or morphotypes) can be generally assigned to ecological niches using overall track size and pace and stride data (i.e., long-legged wading birds vs. short-legged shorebirds). Other track features, such as the extent of interdigital webbing and the degree of rotation of individual tracks in a trackway, may also provide information that allows ichnologists to propose a well-supported modern analogue for the Cretaceous avian trackmaker. In recent years, many novel traces attributed to Mesozoic birds have been described, as well as higher order classifications, such as avian ichnofamilies (Lockley et al., 1992; Lockley, Matsukawa, et al., 2006; Lockley and Harris, 2010). Avian ichnotaxonomy exists to provide a means by which to both document and discuss discrete patterns in the variation of footprint shapes that are attributable to now extinct birds. Ichnotaxonomic groupings for traces identified as avian in origin have the potential to not only identify ecological partitions among extinct avians (Falk, Martin, and Hasiotis, 2011), but also to potentially describe the biologic diversity of known Mesozoic avians whose traces are preserved within the ecological niches of “shorebird” and “wading bird.”

Avian ichnites are assumed to avoid many of the pitfalls ascribed to large vertebrate tracks due to their nature; however, many of the features that are considered synapomorphy-based (presence of halluces) and phenetic-based (e.g., size, digit slenderness, divarication, morphology of unguals) characters are influenced by both anatomical and preservational variation (Buckley, McCrea, and Lockley, 2015, and references within). Avian tracks are subject to metatarsal or “heel” drag and digit drag marks, sediment displacement bulges, track margin collapse, and so on, as seen with features interpreted as toe drag marks in trackways of Pullornipes aureus (Lockley, Matsukawa, et al., 2006). Close examination of multiple qualitative (visual) differences among groups of avian ichnites is more likely to reveal anatomical features of the trackmaker.

The study of avian ichnites, however, is not without challenges. First, the challenge of identifying the potential track-maker of “large bird” versus “small nonavian theropod” for certain ichnotaxa remains despite many efforts to clarify the issue (Lockley, Wright, and Matsukawa, 2001; Wright, 2004; Fiorillo et al., 2011; Xing et al., 2015): this is not surprising given that Aves occur within Theropoda. Wright (2004) observed many bird-like features in dinosaur tracks and noted many of the issues distinguishing the tracks of bipedal, tridactyl dinosaurs and avians that may be subject to similar functional constraints in locomotion. However, theropod locomotion is more hip-driven (Gatsey, 1990; Farlow et al., 2000) than knee-driven, as it is in birds (Rubenson et al., 2007), but the extent to which these factors contribute to qualitative and/or quantitative ichnotaxonomic differences is unknown. Whereas a high average total divarication (~110°) has been used to tentatively identify avian tracks (e.g., Lockley, Wright, and Matsukawa, 2001), using an average calculated from a large sample to determine the identity of one track has the potential to be misleading. The tracks of many extant shorebirds (Scolopacidae) exhibit divarications as low as 75° (i.e., Tringa solitaria, PRPRC NI2012.01 [Peace Region Palaeontology Research Centre]), which is in the range of potential total divarications seen in the tracks of small theropods. Also, divarication can be highly variable within an individual trackway. The total divarication within one extant shorebird trackway (PRPRC NI2012.01) ranges between 75° and 116°, which is an observation that can also be made of fossil bird tracks: tracks from Korea assigned to Aquatilavipes ichnosp. (Huh et al., 2012) range in total divarication from 70° to 134°.

One ichnotaxon in particular is problematic in identifying the affinity of the trackmaker. Magnoavipes (Fig. 15.1A) was first described by Lee (1997) as a trace attributable to a large avian from the Woodbine Formation (Cenomanian) based on the slender digits and wide total divarication. A reanalysis of the ichnogenus led Lockley, Wright, and Matsukawa (2001) to attribute Magnoavipes to a theropod, rather than avian, trackmaker based on large size, lack of a hallux (as seen in extant large wading birds), and narrow trackway. However, Fiorillo et al. (2011) describe a new ichnospecies of Magnoavipes (M. denaliensis) and attribute it to an avian trackmaker based on the high total divarication. The strengths of the opposing diagnostic criteria (high total divarication vs. trackway characteristics) have yet to be statistically tested.

Second, while bird tracks are generally immune to common extramorphologic features sometimes preserved in the tracks of much larger animals, they do exhibit variability in preservation of certain morphologic features, specifically of digit I (hallux) and of webbing. There are examples in the literature where, within an individual trackway, the hallux (i.e., Goseongornipes markjonesi, Kim et al., 2012:fig. 9A) is inconsistent. The presence of semipalmate webbing (webbing restricted to the proximal part of the digits) may be difficult to detect due to sediment consistency and preservation.

A Brief Review of Avian Ichnofamilies from the Mesozoic

There are six ichnofamilies currently attributed to avian traces from the Mesozoic. Refer to the references cited within this section for more detailed information on the systematics of these ichnofamilies and the assignments of the ichnogenera therein.

Avipedidae

Avipedidae (Fig. 15.1B) was originally described by Sarjeant and Langston (1994:12) as containing “avian footprints showing three digits, all directed forward. Digits united or separate[d] proximally. Webbing lacking or limited to the most proximal part of the interdigital angles.” The type ichnogenus for Avipedidae is Avipeda (Vialov, 1965), whose original diagnosis and description was emended by Sarjeant and Langston (1994) to remove the “wastebasket” nature of both Avipeda and the ichnofamily (or morphofamily of Sarjeant and Langston, 1994) for which Avipeda is the type ichnogenus. Sarjeant and Langston (1994) also assign Aquatilavipes swiboldae (Currie, 1981) to Avipedidae. Avipedidae, to date, includes A. swiboldae (Currie, 1981), and A. izumiensis (Azuma et al., 2002).

Limiavipedidae

It has been known for some time (Lockley and Harris, 2010) that Aquatilavipes curriei (McCrea and Sarjeant, 2001) did not match the ichnomorphology of other ichnospecies of Aquatilavipes (A. swiboldae, A. izumiensis). A. curriei prints are attributed to “large, long-legged avian track-maker[s] … [with a] functionally tridactyl pes tracks with no obvious webbing” (McCrea et al., 2014:86). Tracks attributed to Limiavipedidae also possess no hallux impressions and have a pace and stride that are relatively short compared to similarly sized theropod ichnotaxa but that are longer when compared to other avian ichnotaxa. Tracks of the Limiavipedidae are also strongly rotated toward the midline of the trackway. McCrea et al. (2014) erected a novel ichnofamily, Limiavipedidae, for avian ichnotaxa that are attributed to those tracks previously described as A. curriei. Currently, the only two ichnospecies ascribed to Limiavipedidae are Limiavipes curriei (McCrea and Sarjeant, 2001; McCrea et al., 2014) and Wupus agilis (Xing et al., 2015).

Ignotornidae

The ichnofamily Ignotornidae was first erected by Lockley et al. (1992:121) and diagnosed as “tetradactyl, slightly asymmetric bird tracks with variably preserved, posteriorly directed hallux impressions typically showing significant medial rotation towards trackway midline.” Originally, Ignotornidae included both Koreanaornis hamanensis and Jindongornipes kimi, which were originally assigned to the ignotornids based on the presence of a well-defined, posteriorly oriented hallux. However, as more tetradactyl bird tracks were discovered with halluces of varying lengths and orientations, Ignotornidae was revised (by the emendation to Ignotornis by Kim et al., 2006) to include only those ichnotaxa that possess a slight proximal webbing prominent posteromedially oriented hallux impression, including Hwangsanipes choughi (Kim et al., 2006), and Goseongornipes markjonesi (Lockley, Houck, et al., 2006) (Fig. 15.1C).

Koreanaornipodidae

Koreanaornipodidae (Fig. 15.1D) was erected by Lockley, Houck, et al. (2006:95) to include all “small, wide sub-symmetric functionally tridactyl tracks with slender digit impressions, and wide divarication between digits II and IV … small hallux occasionally present and posteromedially directed about 180° away from digit IV.” This differs in the diagnosis of Avipedidae in that a hallux is not usually preserved in avipedids. Koreanaornipodidae includes not only the type ichnogenus K. hamanensis but also K. dodsoni (Xing et al., 2011) and Pullornipes aureusaureus (Lockley, Matsukawa, et al., 2006).

Jindongornipodidae

Jindongornipodidae (Fig. 15.1E) was named by Lockley, Houck, et al. (2006) in their emendation of Ignotornidae. Jindongornipodidae is diagnosed by medium sized tetradactyl tracks with digit II shorter than digit IV, and a moderately long, posteriorly directed hallux (Lockley, Houck, et al., 2006). To date, Jindongornipodidae is a monoichnospecific ichnofamily, whose type ichnospecies is J. kimi (Lockley et al., 1992).

Shandongornipodidae

Shandongornipodidae (Fig. 15.1F) represents traces attributable to tetradactyl, paraxonic, zygodactyl avians (Lockley et al., 2007), and is currently represented by only one ichnospecies, Shandongornipes muxiai (Li et al., 2005).

Rationale for Study

The goals of this study are (1) to examine the current ichnotaxonomic assignments of bird tracks using multivariate statistical analyses for additional statistical support and (2) to examine data of both bird and small theropod tracks and trackways to test other morphologic criteria by which to distinguish between tracks of birds and small theropods. The working hypothesis to be tested is that footprint proportions, as expressed by ratios will reveal significant differences between the tracks of theropods and birds.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Data Used

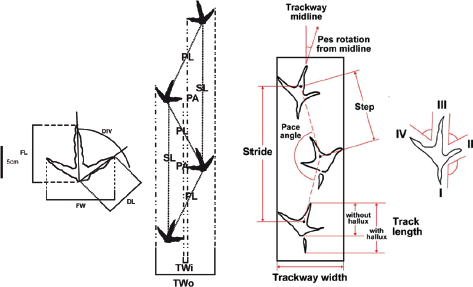

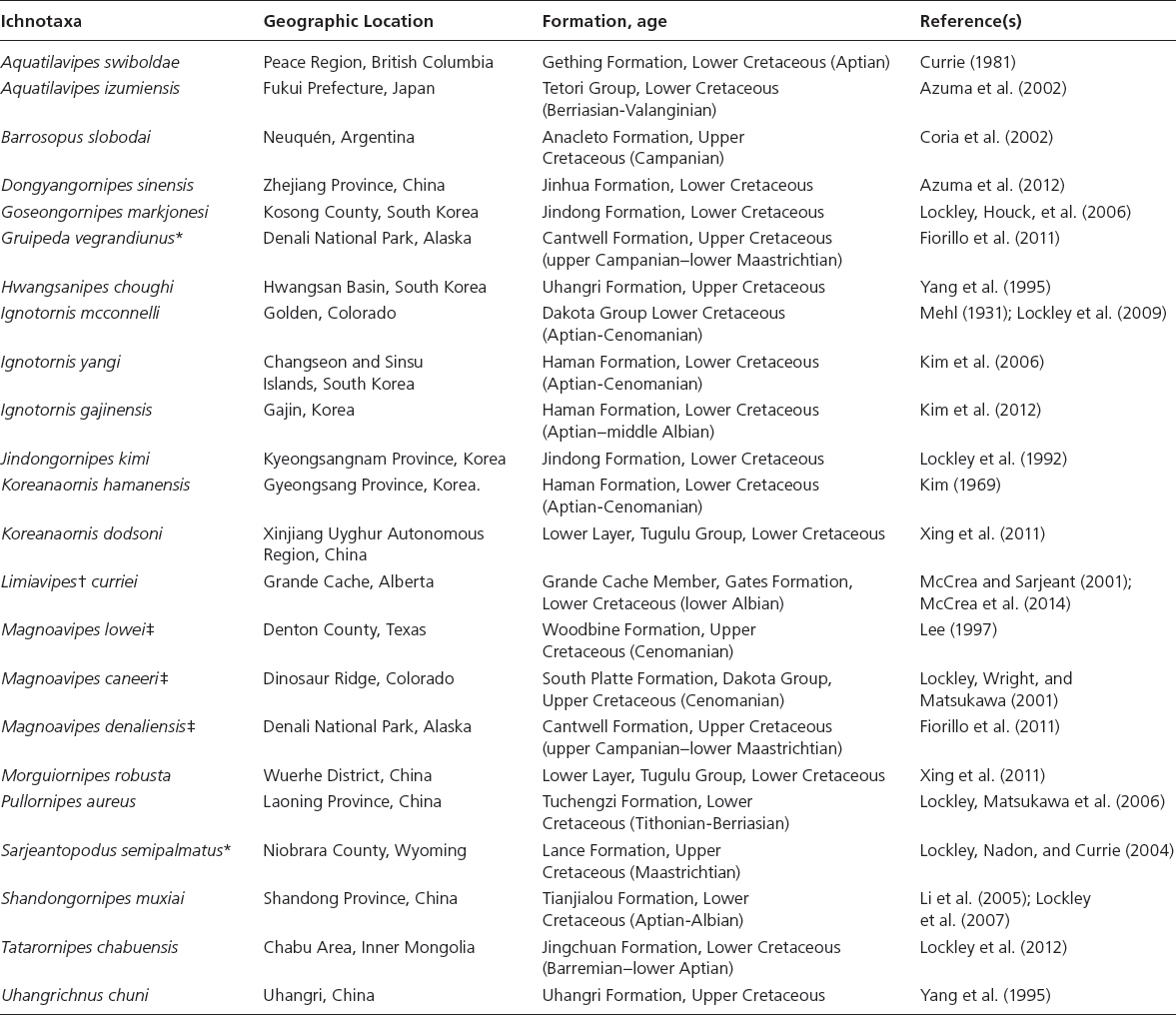

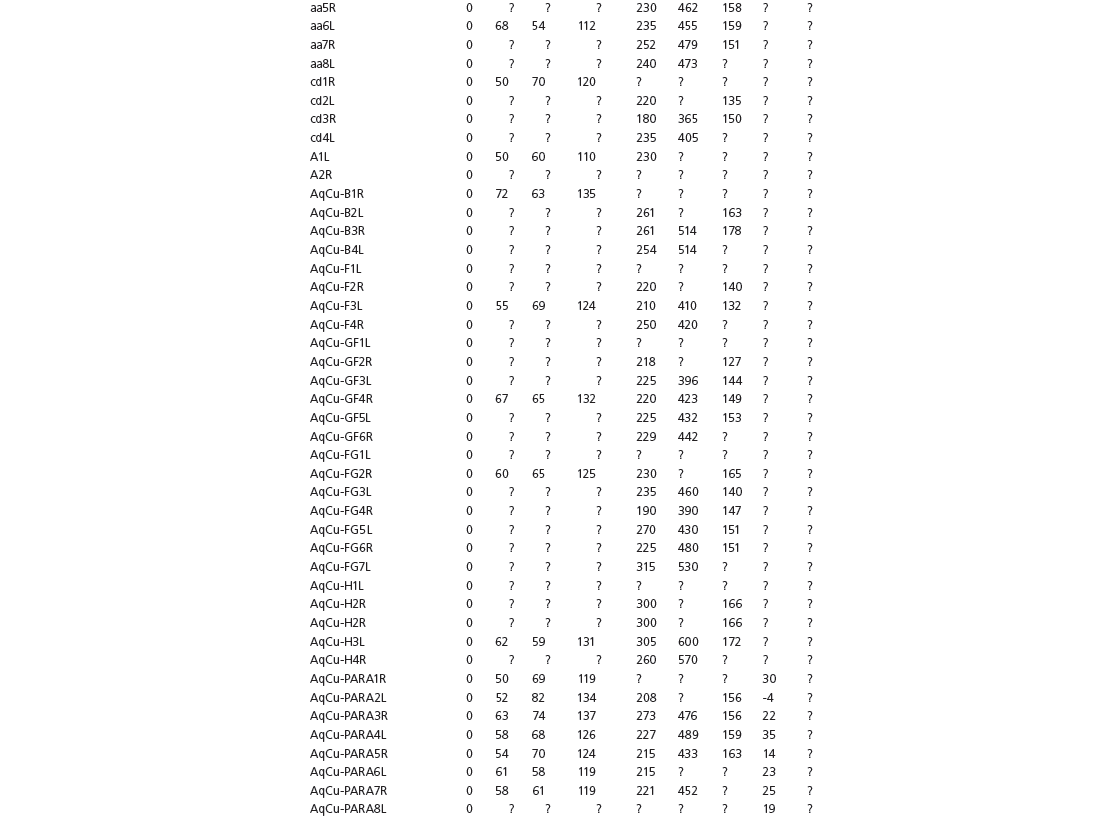

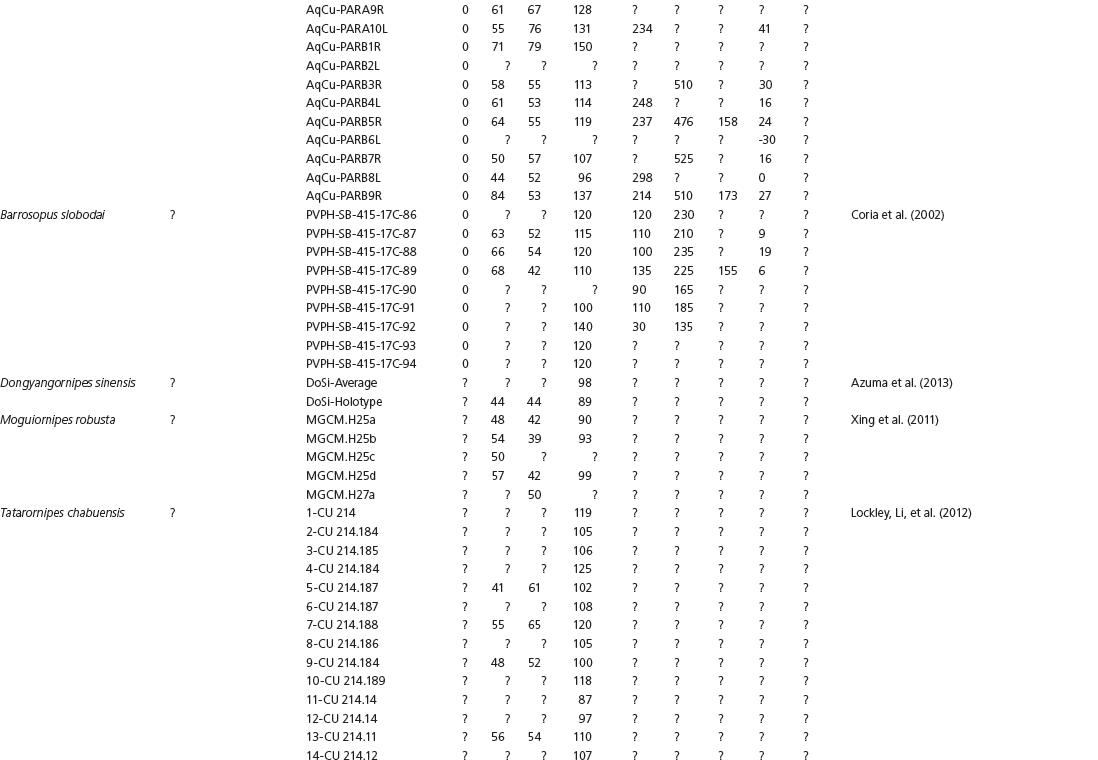

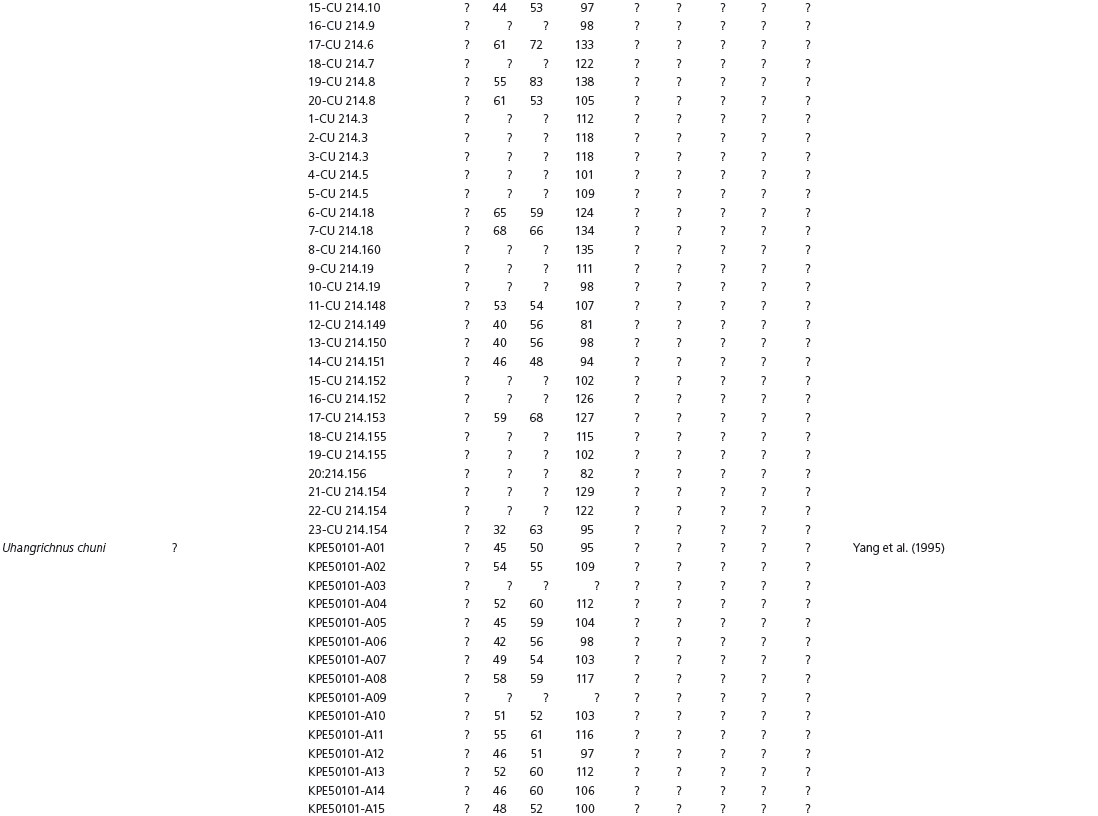

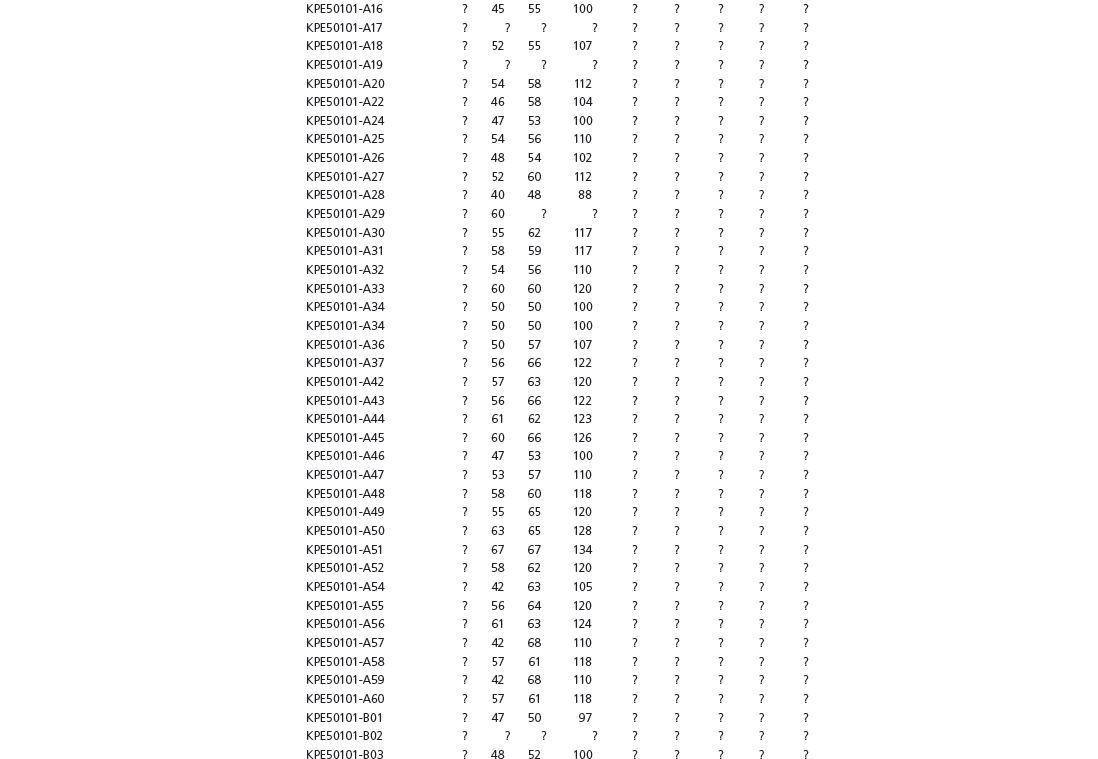

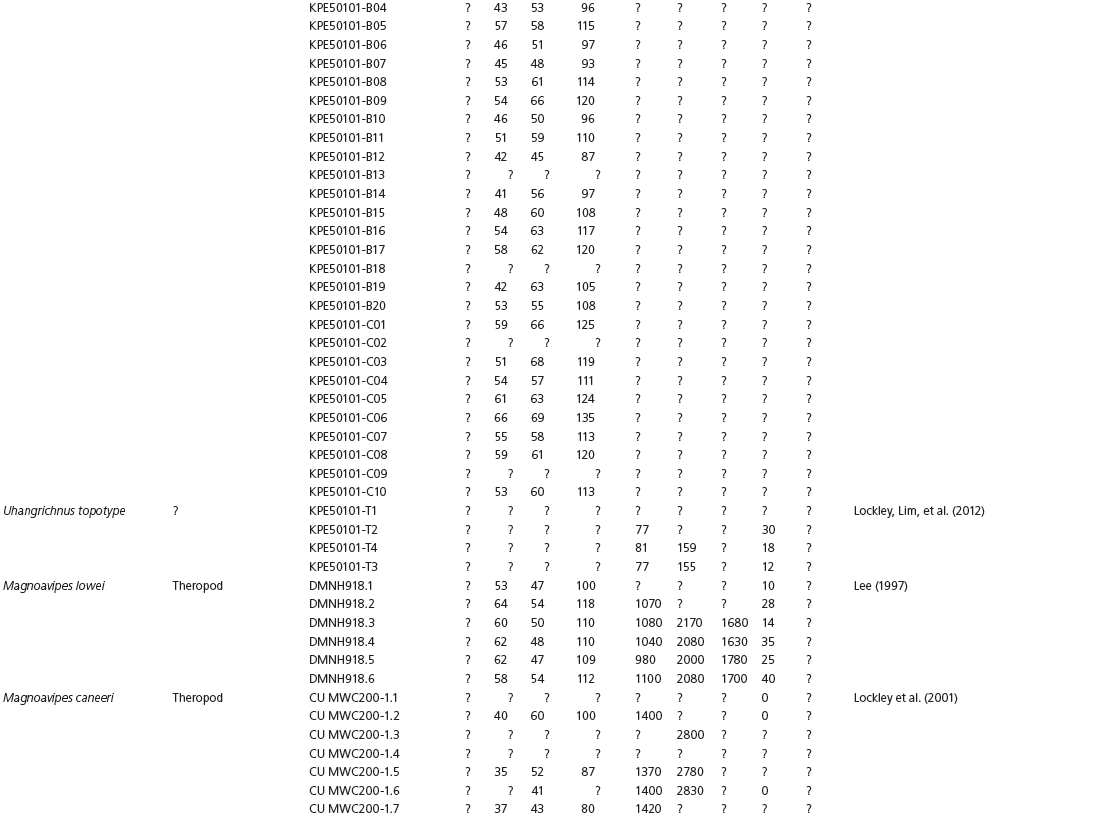

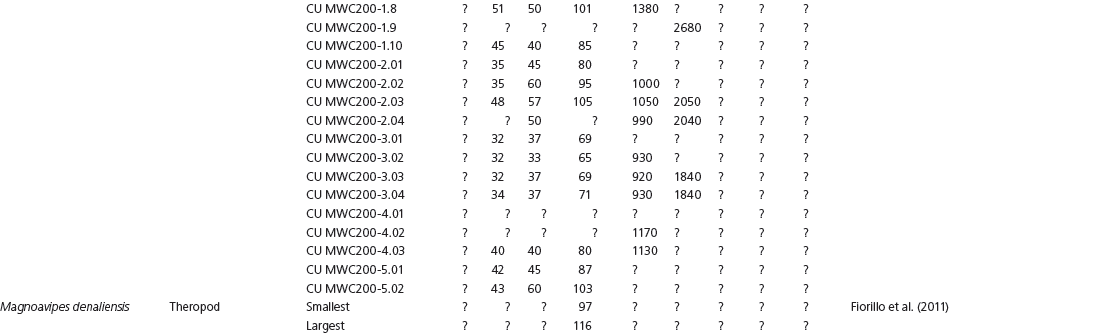

The linear and angular data (App. 15.1) for 584 tracks was collected from ichnotaxonomic descriptions and data tables made available in the avian ichnology literature (see references and App. 15.1 for a complete list). The avian ichnotaxa examined in this study are listed in Table 15.1. The amount and types of data collected varied considerably: some data reported only maximum values and averages for the ichnotaxa were reported, whereas the data for all measured tracks were presented for other ichnotaxa (App. 15.1).

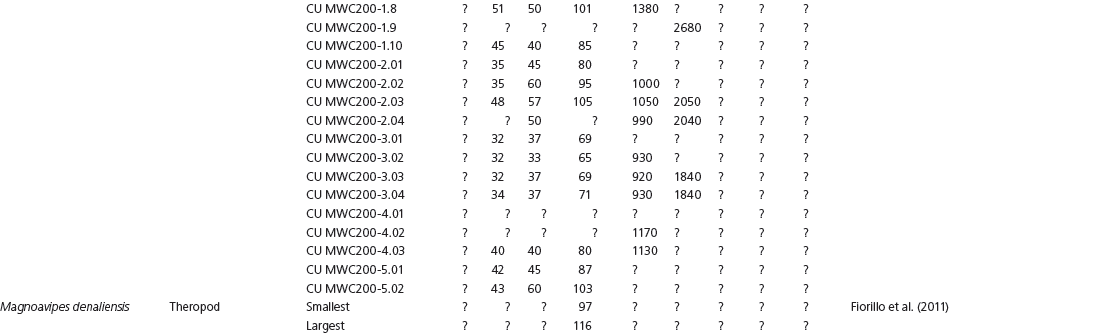

Table 15.1. Avian ichnotaxa used in this study

Source: Amended from Lockley and Harris (2010)

Notes: * Denotes ichnotaxa for which there is too little data reported to be used in the multivariate statistical analyses. † The ichnospecies Aquatilavipes curriei (McCrea and Sargeant, 2001) has been recently redescribed as not belonging to the ichnogenus Aquatilavipes but reassigned to the ichnofamily Limiavipedidae and redescribed as Limiavipes curriei (McCrea et al., 2014). ‡ Denotes ichnotaxa whose assignment to Aves is contentious: Lockley, Wright, and Matsukawa (2001) convincingly demonstrate that Magnoavipes is an ichnogenus attributed to theropods.

Standardization of Data

Data also varied in the number of variables that were reported. Some ichnotaxa were reported only with their length, width, and total divarication, whereas other ichnotaxa were presented with more comprehensive data. All data were converted to millimeters. Data were entered to fit into a standard table (App. 15.1). Data that were not available, either due to exclusion in the published data sets or due to incompleteness of the measured tracks, were entered as a question mark. The data set is set up to accommodate tetradactyl tracks (digits I–IV), and for tridactyl tracks digit I was coded as 0 mm (rather than a question mark for missing) to indicate the absence of that digit for the ichnotaxon in question. For ichnotaxa with trackways where digit I is inconsistently preserved, however, digit I was coded as a question mark to indicate missing data. This allows for tridactyl and tetradactyl tracks to be analyzed together, and the structural presence (or absence) of digit I to be recognized in the total analysis. If digit I were coded as a question mark for functionally tridactyl footprints, the multivariate program Paleontological Statistics (PAST) version 2.17 would treat functionally tridactyl tracks as having missing data and use pair-wise substitution (Hammer, Harper, and Ryan, 2001) for the value digit I instead of recognizing that digit I was not present.

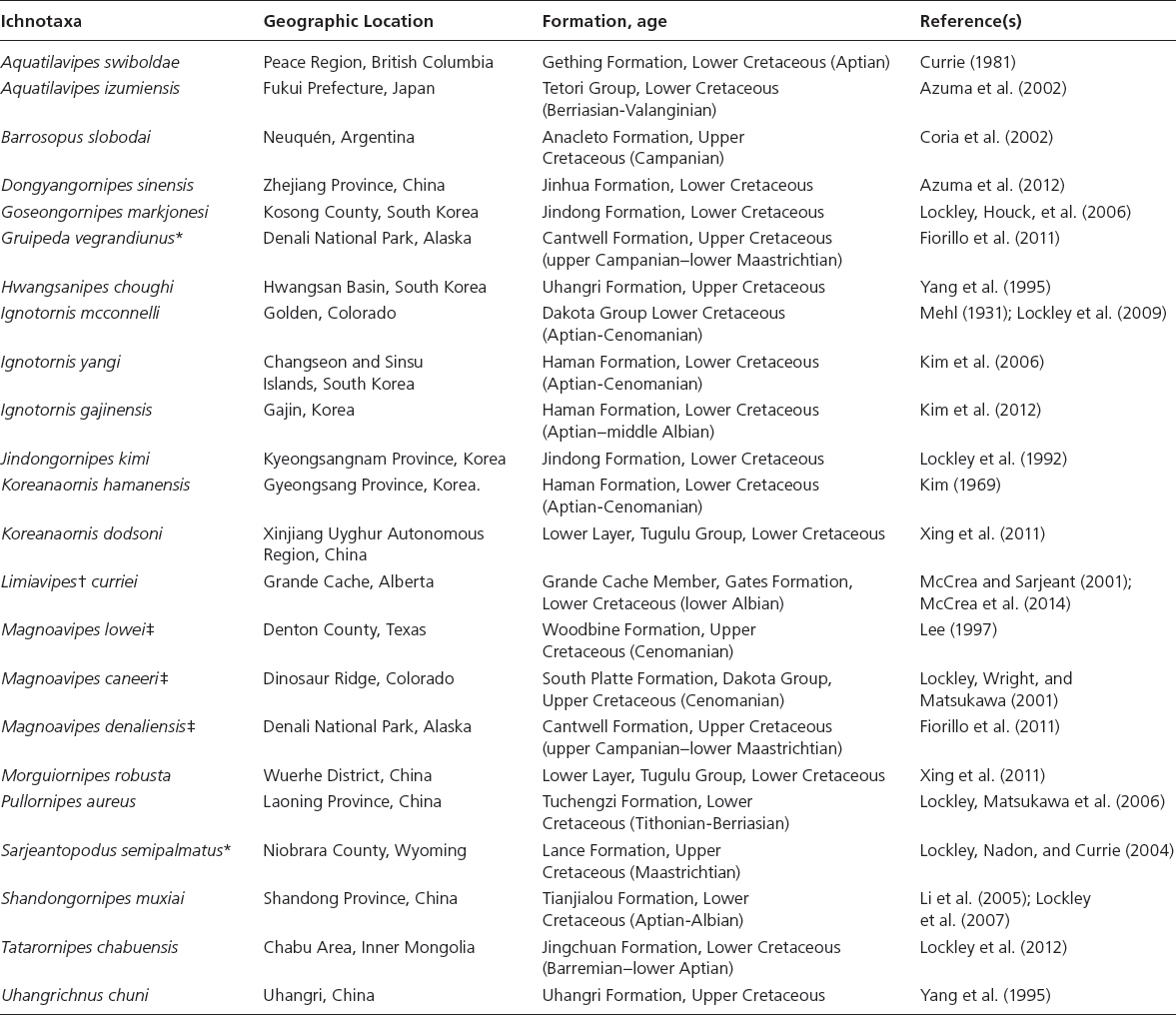

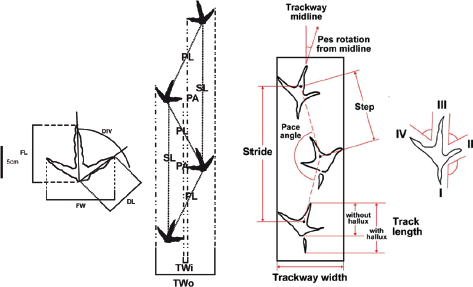

Linear measurements

The following linear measurements are used in this study.

• Digit lengths (DL): the lengths of the individual digits (DL-I, digit I length; DL-II, digit II length; etc.) as measured from either the footprint center or the entire preserved proximodistal length of the footprint, whichever is best preserved;

• Digit widths (DW): the mediolateral widths of the individual digits (DW-I, digit I width; DW-II, digit II width; etc.) as measured at the most proximal point of the free digit;

• Footprint center: not a linear measurement but a point of reference, as measured from straight lines drawn from the distal ends of digits II–IV to their proximal point of convergence;

• Footprint length (FL): the distance as measured from the caudal (posterior) margin of the metatarsal pad (or, lacking the preservation of the metatarsal pad, the caudal points of digits II and IV) to the most distal end of digit III. In some cases, the length of digit III is used as FL;

• Footprint length with hallux (FLwH): the distance as measured from the distal tip of digit III to the distal tip of digit I. If no hallux is present, FLwH is treated the same as the same as FL;]

• Footprint width (FW): the distance as measured from the most distal point of digit II to the most distal point of digit IV;

• Pace length (PL): the distance measured from a distinct point (usually footprint center) on one footprint to the next footprint in the sequence of the trackway (left footprint to right footprint, or right footprint to left footprint);

• Stride length (SL): the distance measured from a distinct point (usually footprint center) from left footprint to left footprint, or from right footprint to right footprint.

Angular measurements

The following angular measurements are used in this study.

• Divarication of digits I and II (DIV I–II): the angle formed between the distal points of digits I and II, with the footprint center as the origin of the angle;

• Divarication of digits II and III (DIV II–III): the angle formed between the distal points of digits II and III, with the footprint center as the origin of the angle;

• Divarication of digits III and IV (DIV III–IV): the angle formed between the distal points of digits III and IV, with the footprint center as the origin of the angle;

• Footprint rotation (FR): the angle at which the individual footprint is rotated toward (positive) or away (negative) from a straight line running through the center of the footprint that is parallel to the midline of the trackway;

• Pace angulation (PA): the angle formed by three consecutive footprints in a trackway, with the angle formed at the footprint center of the middle footprint of the consecutive sequence;

• Total divarication (DIVTOT): the angle formed between the distal points of digits II and IV, with the footprint center as the origin of the angle. DIVTOT is also known in the literature as DIV II–IV.

Ratios

Ratios are useful in comparing ichnologic data as they remove the size component from the analyses.

• Footprint length to footprint width ratio (FL/FW): the ratio obtained by dividing FL by FW. This value can also be described as the splay of the digits of a footprint. FL/FW is the only ratio that is consistently calculated in vertebrate ichnology.

Digit length ratios: the ratios of the different digit lengths provide the relative lengths of one digit as compared to the other digit in the ratio. The following digit length ratios are used in this analysis.

• DL-I/DL-II: the ratio of digit I length and digit II length;

• DL-I/DL-III: the ratio of digit I length and digit III length;

• DL-I/DL-IV: the ratio of digit I length and digit IV length;

15.2. Measurements collected for avian ichnites. (Left) Complete data that is recommended to be collected (where possible) for both previously described and novel avian ichnotaxa; (right) an example of thorough data collection in the reassessment of Ignotornis mcconnelli (Lockley et al., 2009). Abbreviations: DIV, digit divarication; DL, digit length; FL, footprint length; FW, footprint width; PA, pace angulation; PL, pace length; SL, stride length; TWi, inner trackway width; TWo, outer trackway width.

• DL-II/DL-III: the ratio of digit II length and digit III length;

• DL-IV/DL-III: the ratio of digit III length and digit IV length.

Divarication ratios: the ratios of divarication data describe the percentage of splay on each lateral side of the footprint of the total divarication. The following digit divarication ratios are used in this study.

• DIV II–III/DIVTOT: the percentage of divarication between digits II–III of the total divarication;

• DIV III–IV/DIVTOT: the percentage of divarication between digits III–IV of the total divarication;

• DIV II–III/DIV III–IV: the ratio of DIV II–III as compared to DIV III–IV.

Statistical Analyses

Bivariate and multivariate analyses on the avian and theropod data set were performed using PAST version 2.17 (Hammer, Harper, and Ryan, 2001). Analyses performed were the t-test (bivariate), and principle component, discriminant, and canonical variate analyses (i.e., multivariate; Hammer and Harper, 2006).

Principal components analysis (PCA) is the two-dimensinoal (2-D) projection of multivariate data to identify the components that account for the maximum amount of variance in the data (Hammer and Harper, 2006). It reveals the relative variation contributed to the data set by each measured variable, produces principal component ordinance plots that visually project three-dimensinoal (3-D) plots of specimens in 2-D, and may reveal discrete groupings among specimens. PCA ordinance plots are often displayed with variance vectors that show the relative amount of variation that each measured variable contributes to the overall variation in the data set (Hammer and Harper, 2006). The first principal component (PC1) represents variation based on size (even in log-adjusted data) and is usually the largest principal component in terms of percentage of total variance within the sample (Hammer and Harper, 2006). However, careful examination of the variance vectors is required to determine the exact nature of PC1. PCA was used to find the percentage of total variation (variance) that each measured variable, or combination of variables, contributed to the total variation in the data set. It replaces missing data using pairwise substitution (Hammer, Harper, and Ryan, 2001). The strength of PCA is not in determining the significance of the differences among qualitative groupings – PCA is not statistics (Hammer and Harper, 2006) – but in revealing which variables contribute to distinguishing among ichnotaxonomic groups.

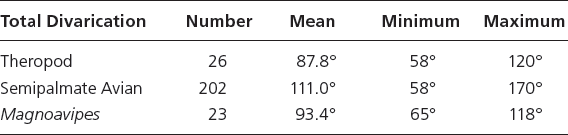

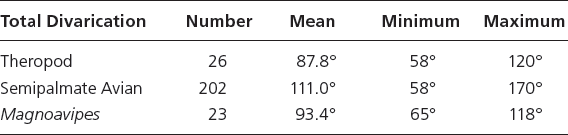

Table 15.2. Comparative total divarication data for Mesozoic tridactyl semipalmate avian tracks, the tracks of the ichnogenus Magnoavipes, and Early Cretaceous theropod tracks

Note: The data show that, although there are large differences among the mean total divarications of the three groups, the minimum and maximum value range has a great deal of overlap. This amount of variation between the total divarication of theropod and bird tracks makes using the average total divarication value (or the total divarication of an isolated footprint) problematic.

Discriminant analysis (DA) projects a multivariate data set down to one dimension in a way that maximizes separation between two a priori separated groups: in this case, the a priori groups are ichnotaxonomic assignments of Mesozoic bird tracks. This is a useful tool for testing hypotheses of morphologic similarity or difference between two groups. A 90% or greater separation between two groups is considered sufficient support for the presence of two taxonomically distinct morphotypes (Hammer and Harper, 2006); however, 100% is ideal. Canonical variate analysis (CVA) compares specimens a priori categorized in three or more groups using the same principles as DA does. The psame between two a priori groups was determined using Hotelling’s t-squared test (the multivariate version of the t-test; Hammer and Harper, 2006) to determine significance at p ≥ .05.

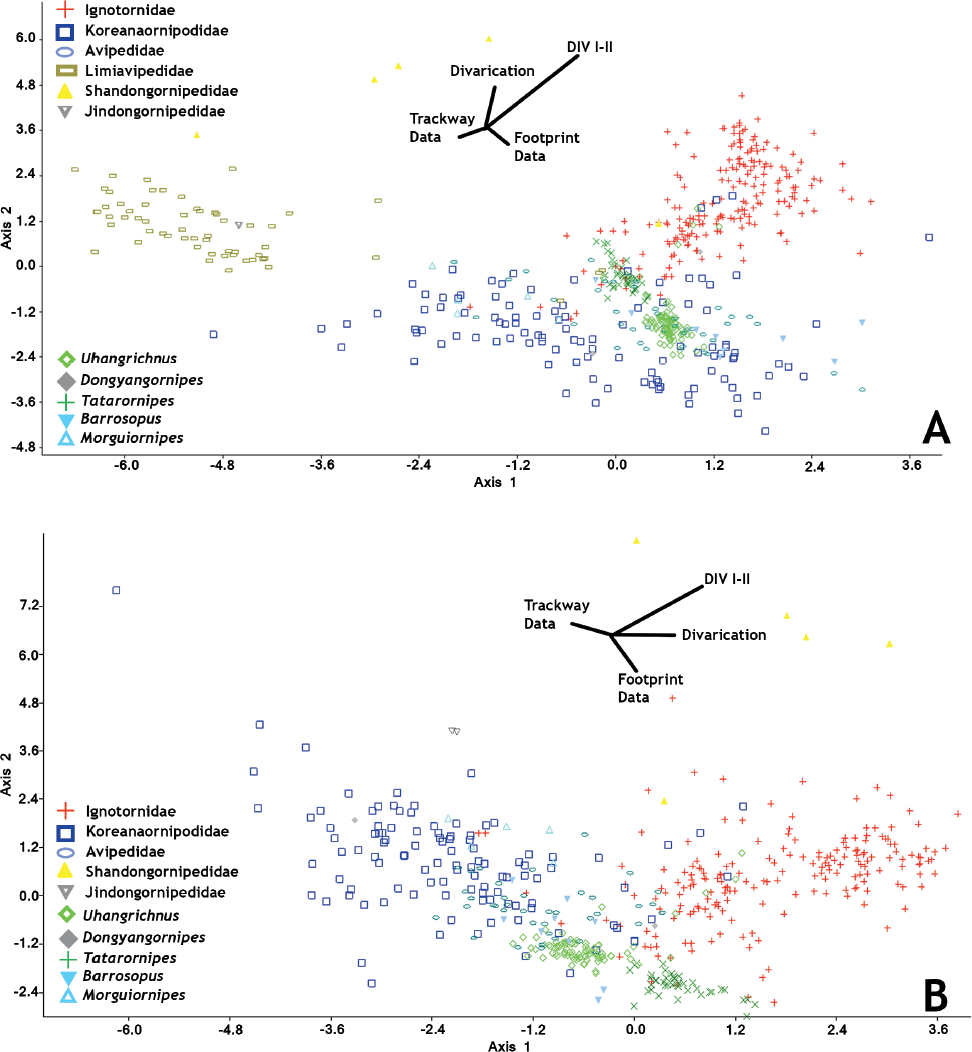

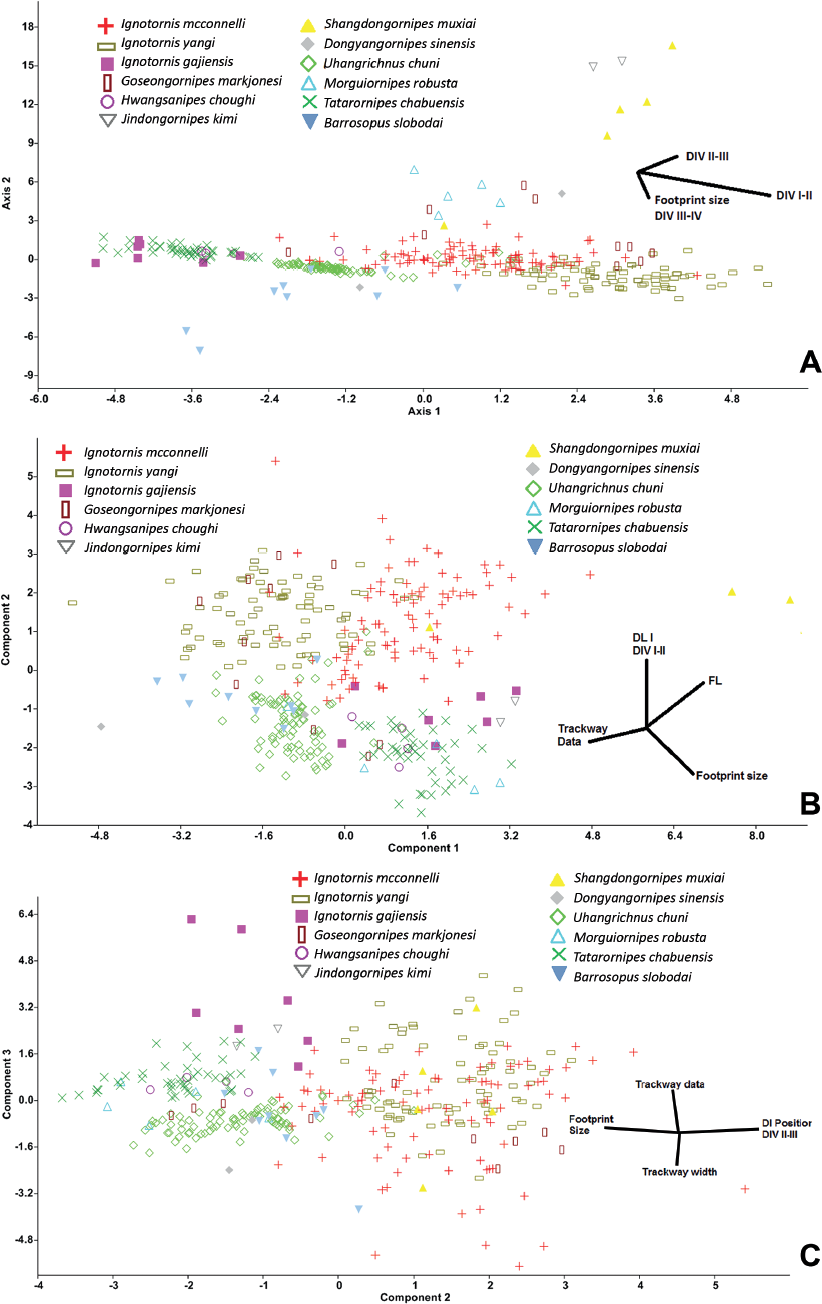

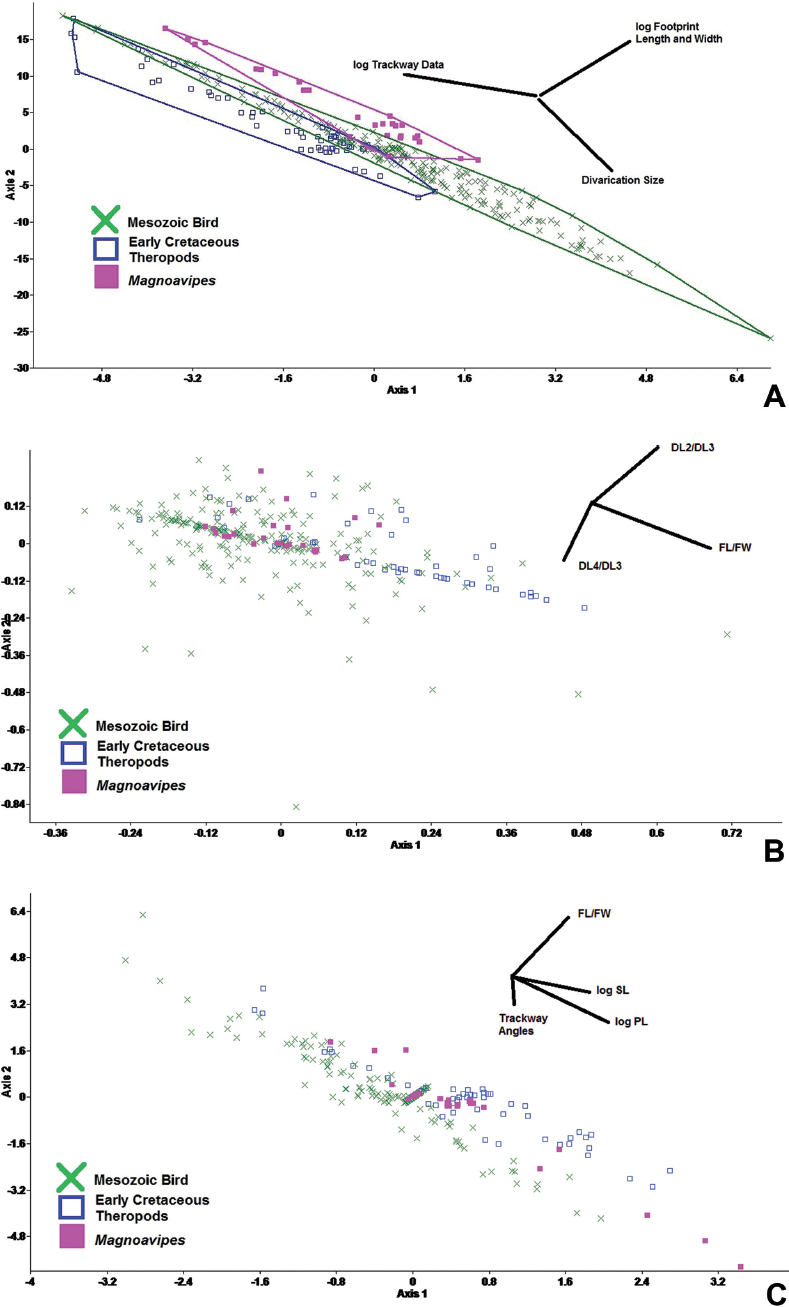

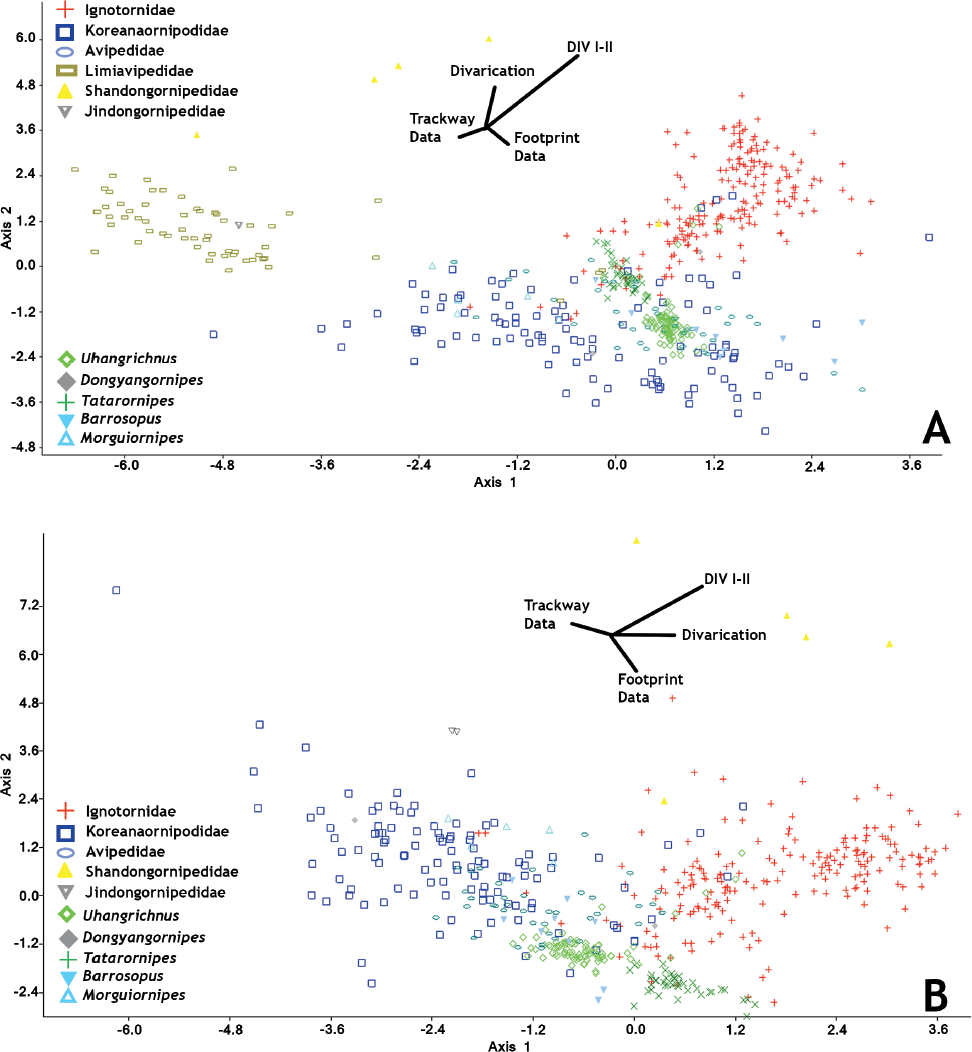

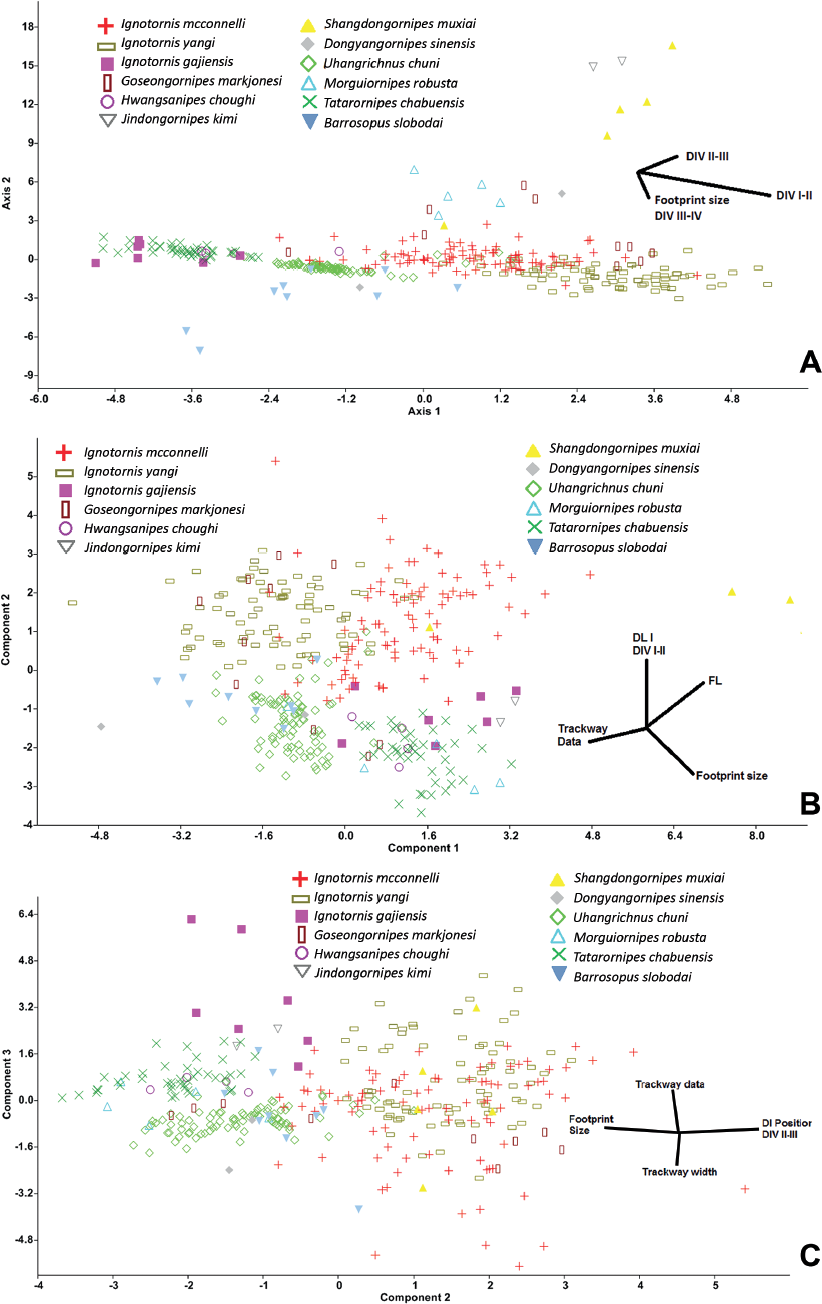

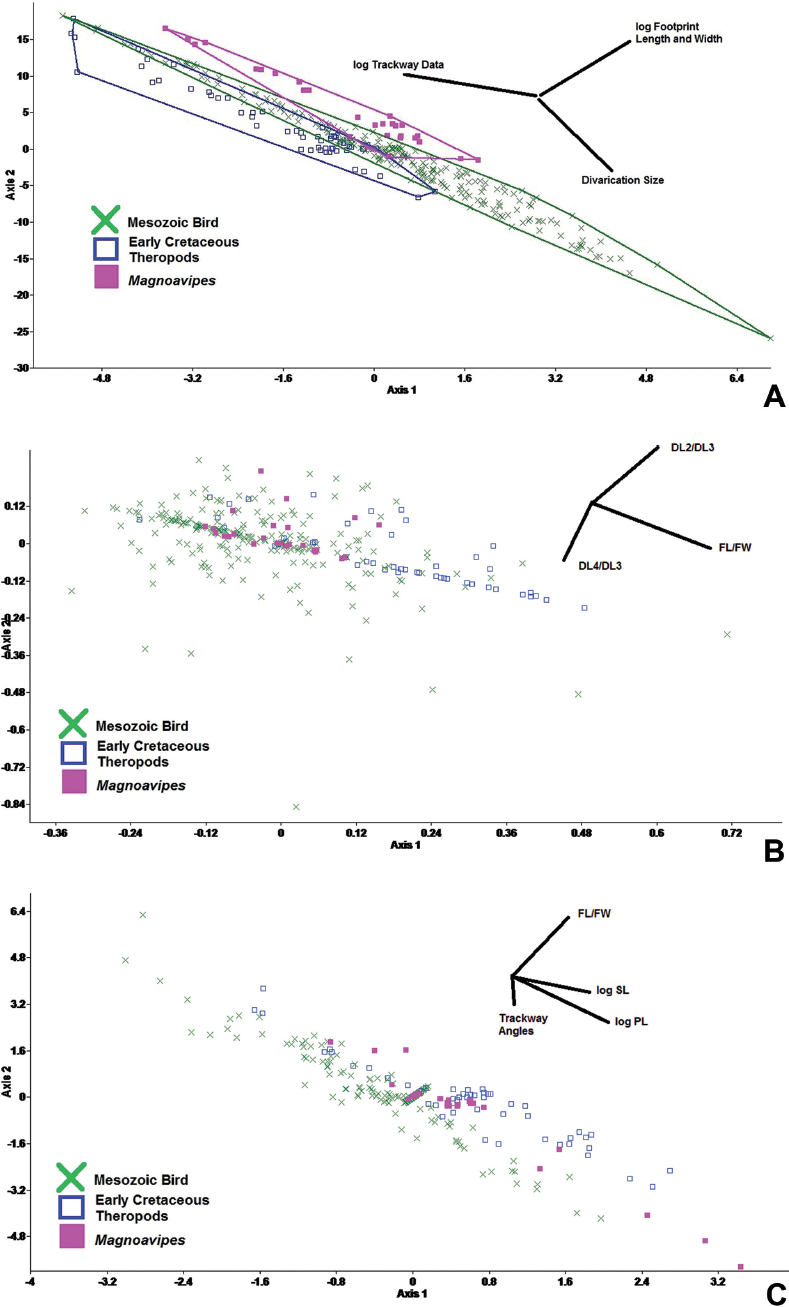

15.3. (A) Canonical variate analysis plot of all Mesozoic avian ichnofamilies (except for Sarjeantopodus and Gruipeda, see Table 15.1). The inclusion of the Limiavipedidae (Limiavipes curriei), whose tracks are much larger than the rest of the Mesozoic avian ichnotaxa, restricts the other ichnotaxa data points into one section of morphospace. All avian ichnogenera as categorized as ichnofamilies are shown to be significantly different from one another, despite their apparent overlap in morphospace (Table 15.3). (B) Canonical variate analysis plot of Mesozoic avian ichnofamilies excluding Limiavipes curriei. The removal of the much larger L. curriei allows for a more accurate analysis of the smaller avian ichnotaxa. There is a general grouping between tridactyl (lower left) and tetradatyl (upper right) avian tracks. Shandongornipes muxiai and Dongyangornipes sinensis cluster discretely from the rest of the analyzed Mesozoic avian tracks. Vectors show the relative amounts of variation each measured variable contributes to the total data set. Abbreviation: DIV, digit divarication.

Challenges and Assumptions of Performing Multivariate Statistical Analyses on Ichnologic Data

Limited data and small sample size

In the cases where only maximum values and averages were presented in ichnotaxonomic descriptions, those ichnotaxa provided limited data to the overall analysis. Sample sizes of less than three will cause a multivariate analysis of a specimen to fail. Despite their limited contribution of variation data, J. kimi, D. sinensis, and M. denaliensis were left in most of the analyses to determine where in morphospace these ichnotaxa were likely (but not conclusively) to group if more data were available. However, only sparse data (or the mean values of data) for Sarjeantopodus semipalmatus (Lockley, Nadon, and Currie, 2004) and Gruipeda vegrandiunus (Fiorillo et al., 2011) were provided with the ichnotaxonomic descriptions, and they were not included in the analyses.

Assumption of consistency in data collection techniques

Unless specifically described in the methodology section of each published data source (i.e., Lockley et al., 2009) (Fig. 15.2), there is an assumption of a general standardized method for collecting both track and trackway data for the analyses herein.

The importance of size in multivariate statistical analyses of avian tracks

Given the large size range of the ichnotaxa in this study, analyses were conducted on log10-transformed data. However, there is justification for performing both nontransformed and log10-transformed data. Extant shorebirds reach adult size quickly, decreasing the likelihood that a significant difference in size between two ichnomorphotypes is ontogenetic. Although shorebird young are precocial and their young mature at a slower rate relative to birds with altricial young (Gill, 2007), the young of shorebirds reach maturity quickly: young of Charadrius vociferus (killdeer) leave the nest within 24 hours of hatching, and at day 17 the growth curve of chicks asymptotes (Bunni, 1959; Jackson and Jackson, 2000), and the young of Actitis macularia (spotted sandpiper) reach 82% of their adult wing-tip to wing-tip length at day 15 (Oring, Graym, and Reed, 1997). In terms of hind limb development, long bones of the hind limb are roughly 30% to 35% of adult length at the time of hatching in Larus californicus (California gull) and increase isometrically (along with foot surface area) with body mass (Carrier and Leon, 1990). Unless two different track size classes are documented within the separate ichnotaxon in question, it is parsimonious to assume that the trackmakers of each ichnotaxon are of or approaching adult size. Two avian ichnotaxa that exhibit a significant difference in size may reflect two separate track-making species. The quick attainment of adult body size by many extant shorebirds allows us to assume that, given their equal investment in both cursorial and aerial locomotory modes (Dial, 2003), shorebird hind limbs become functional shortly after hatching (Carrier and Leon, 1990) and foot length of shorebirds reaches adult body size within days to weeks (Bunni, 1959; Carrier and Leon, 1990; Oring, Graym, and Reed, 1997; Jackson and Jackson, 2000).

A priori groupings and contentious avian ichnotaxa

One must proceed with caution when comparing data from ichnotaxa that have different potential trackmakers with a potential for large morphological similarities. Only specimens for which the affinity of the trackmaker is unambiguous should be used in a multivariate statistical analysis, as many of the comparisons rely on accurate a priori ichnotaxonomic assignments, especially when testing the strength of ichnotaxonomic assignments.1 As such, ichnologic specimens from the Jurassic Period are not considered, because there is not enough data available to determine whether the trackmakers were true Avialae, nonavian theropods or whether they belonged to an intermediate branch of the theropod – avian phylogeny.

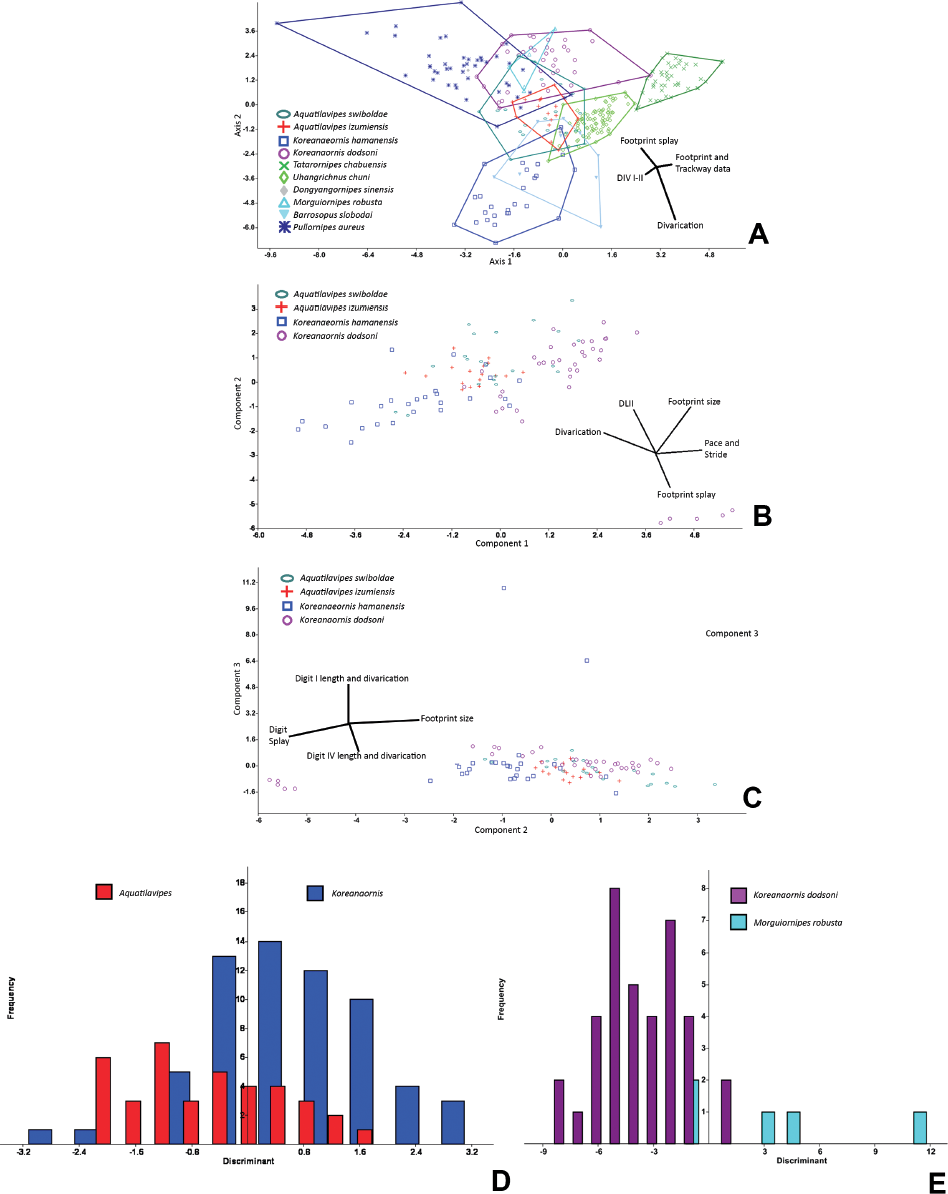

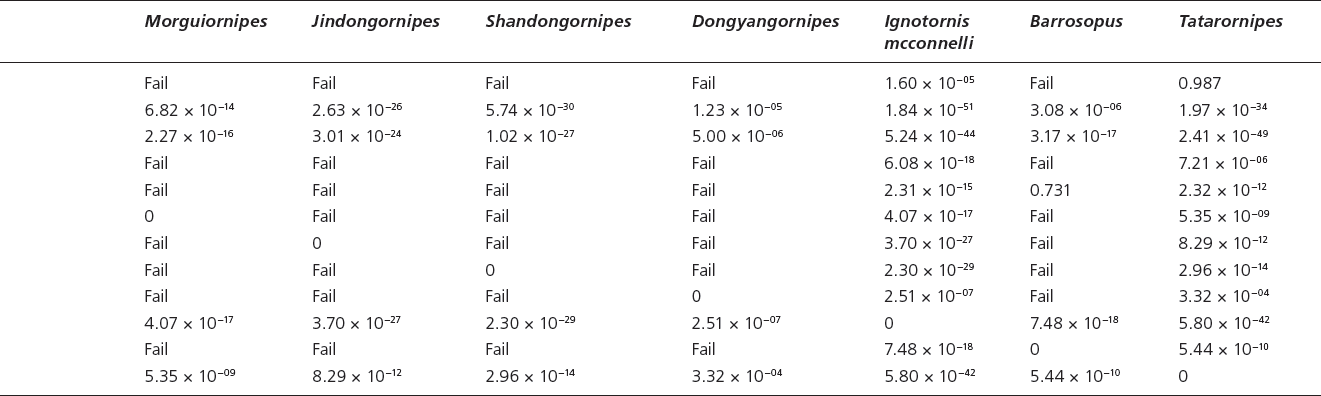

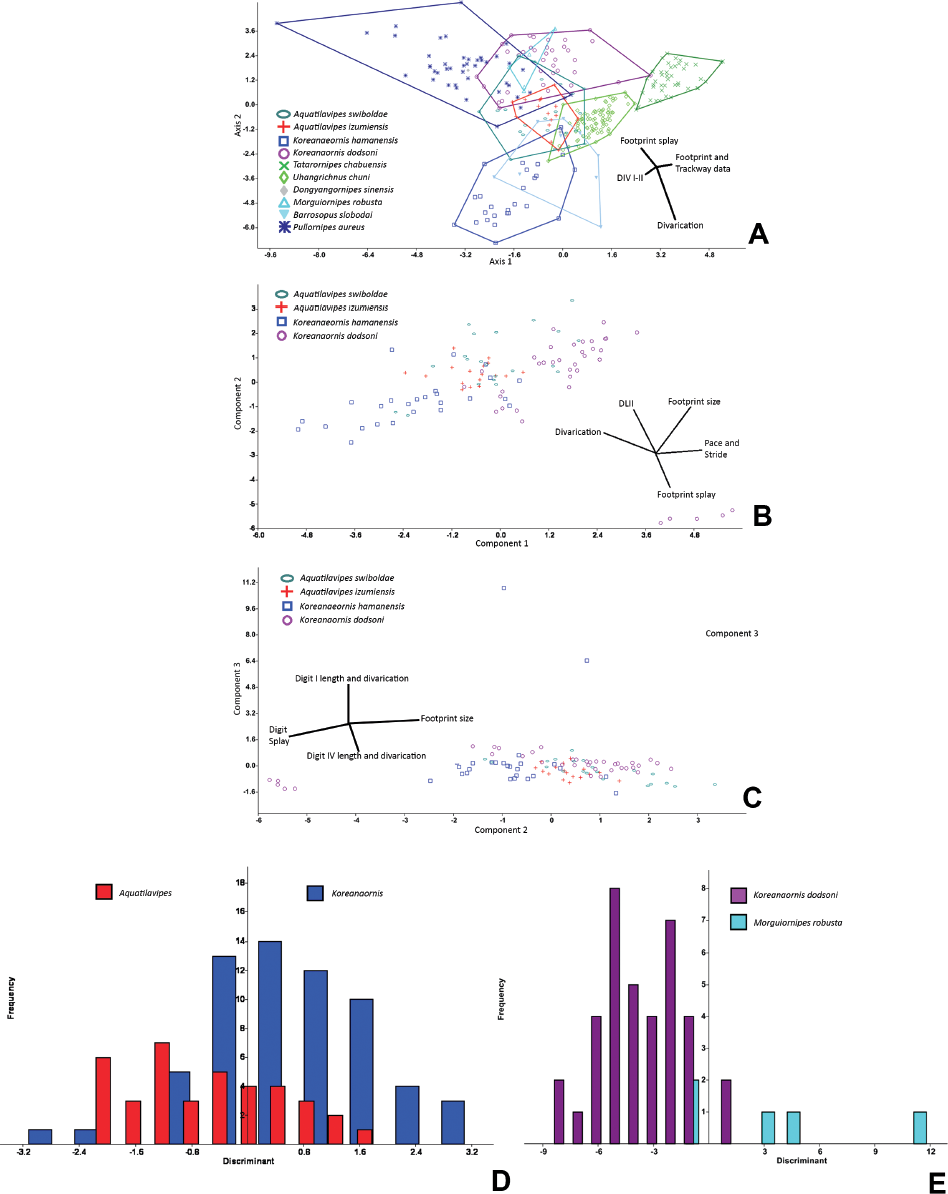

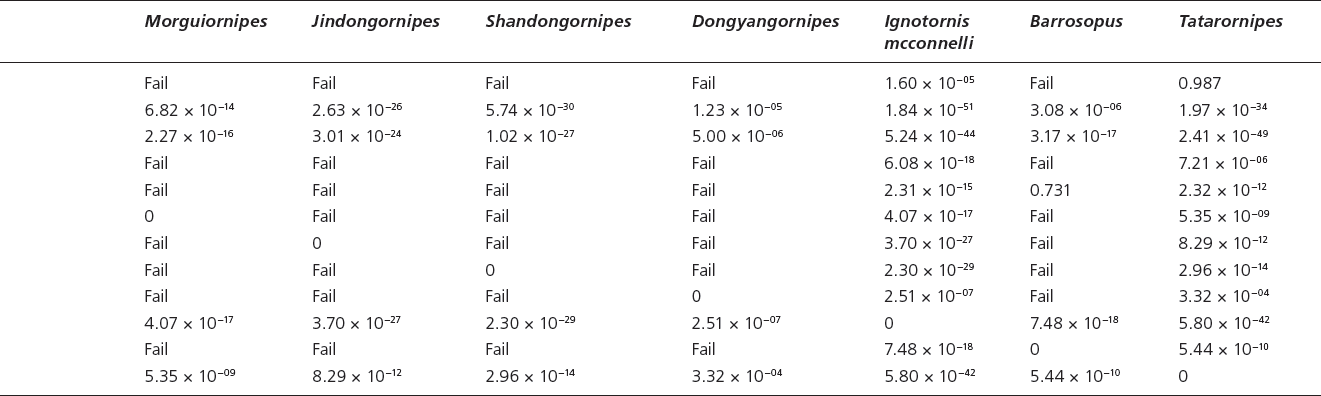

15.4. (A) Canonical variate analysis plot of the ichnospecies of Avipedidae (Aquatilavipes izumiensis, A. swiboldae), the Koreanaornipodidae (Koreanaornis hamanensis, K. dodsoni, Pullornipes aureus) and those ichnotaxa not currently assigned to an ichnofamily (Uhangrichnus, Dongyangornipes, Barrosopus, Morguiornipes, Tatarornipes). Despite being assigned to the same ichnogenus, K. hamanensis and K. dodsoni are significantly different and have 100% separation in morphospace. Due to the overall similarity in shape, there is a great deal of morphospace overlap between the avipedids and the koreanaornipedids. Tatarornipes forms a discrete cluster, suggesting that Tatarornipes does not belong within either the avipedids or the koreanaornipedids. (B) Principal component (PC) analysis graphical results of PC1 (footprint size) and PC2 (divarication/digit splay ratio) axes of ichnospecies of Avipedidae (Aquatilavipes izumiensis, A. swiboldae) and Koreanaornipodidae (Koreanaornis hamanensis, K. dodsoni, Pullornipes aureus), with ichnospecies unassigned to an ichnofamily. (C) Principal component analysis graphical results of PC2 (digit divarication/splay ratio) and PC3 (digit I length/DIV III–IV ratio) axes of ichnospecies of Avipedidae (Aquatilavipes izumiensis, A. swiboldae) and Koreanaornipodidae (Koreanaornis hamanensis, K. dodsoni, Pullornipes aureus), with ichnospecies unassigned to an ichnofamily. Pullornipes has a relatively larger pace and stride, whereas Barrosopus has relatively larger digit lengths. (D) Discriminant analysis graphical results of a comparison between the ichnogenera Aquatilavipes and Koreanaornis. The similarity between the two ichnogenera makes the results of the discriminant analysis contradictory: the two groups are significantly different (psame = 9.80 × 10−04), yet the percentage of individual prints correctly assigned to their a priori groups was only 72.3%. (E) Discriminant analysis on Koreanaornis dodsoni and Morguiornipes. Despite the large amount of overlap between the two ichnotaxa in Figures 15.5A–15.5C, these two taxa are not significantly different (psame = .0569), with 90.5% of the footprints correctly assigned to their a priori determined groups. Abbreviations: DIV, digit divarication; DL, digit length.

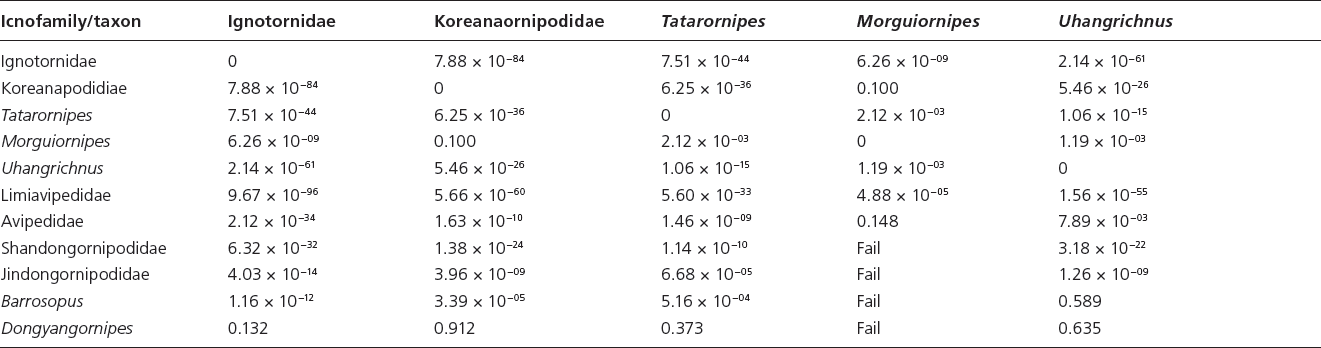

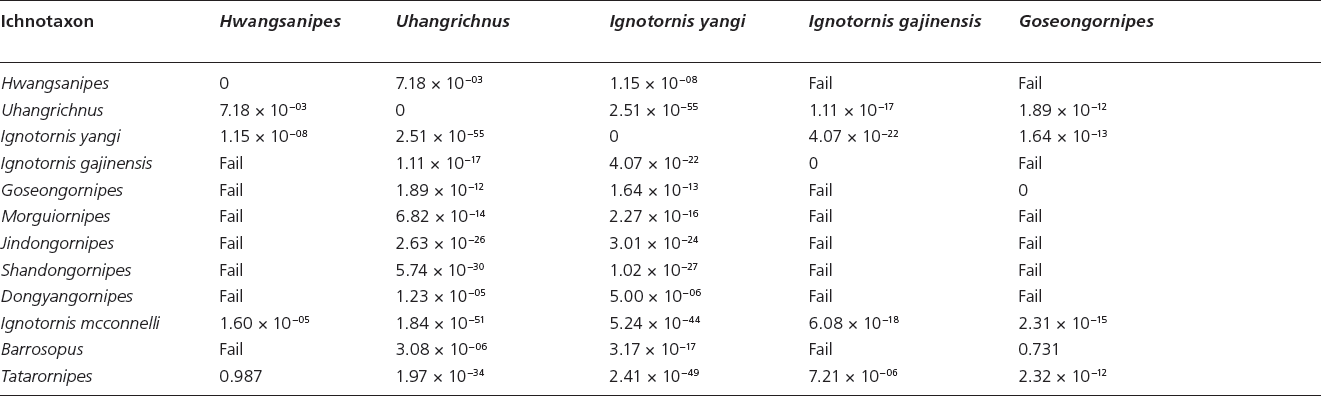

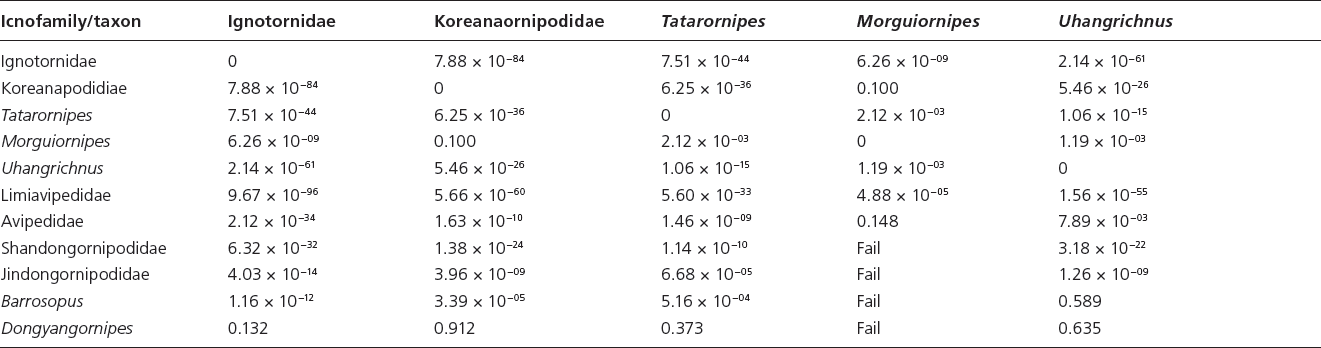

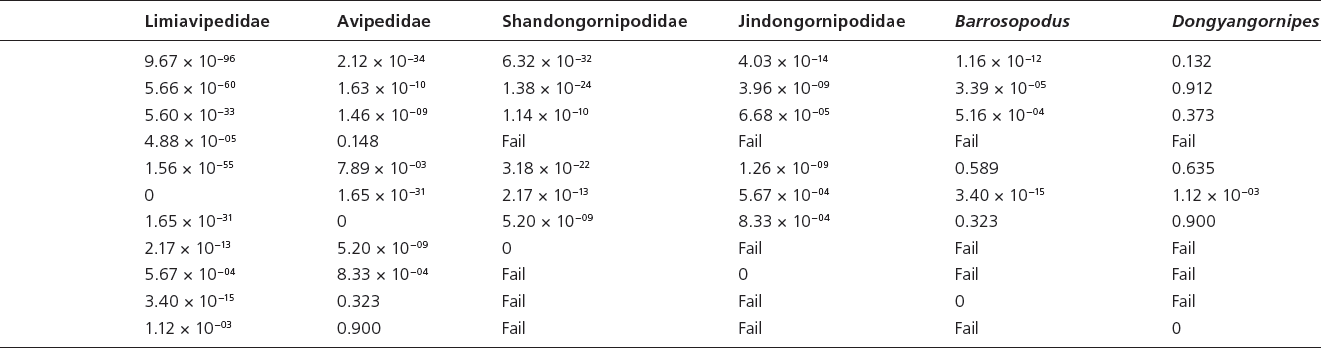

Table 15.3. Canonical variate analysis results of log10-transformed linear and unadjusted angle data (App. 15.1) of Mesozoic avian ichnotaxa a priori assigned to current ichnofamilies and those Mesozoic avian ichnotaxa currently unattributed to ichnofamilies

Note: “Fail” indicates a priori groups for which too few data were available for statistical analysis

Ichnotaxa for which the trackmaker is of debatable affinity are also problematic in a multivariate statistical analysis. For example, the trackmaker for the ichnogenus Magnoavipes has been described by different authors as either avian (Lee, 1997; Fiorillo et al., 2011) or theropod (Lockley, Wright, and Matsukawa, 2001) (Table 15.2). In such cases, the strength of the a priori assignment of either avian or theropod for the ichnotaxon in question may be tested in separately run analyses.

Also, PAST version 2.17 does not offer more than 16 separate symbols for a priori categorization of specimens. This required that the ichnotaxa be a priori grouped by ichnogenera when analyzing all specimens. Specimens were coded as ichnospecies when in smaller analyses that involve fewer a priori groupings.

RESULTS

Support for Current Avian Ichnotaxonomic Assignments

Avian ichnofamilial assignments

Canonical variate analyses show that there is strong statistical support for all ichnofamilies analyzed (Hotelling’s t-squared: psame <<< .01) (Table 15.3). There is overlap in the graphical projection of the 3-D data onto a 2-D xy graph (Fig. 15.3A). The inclusion of L. curriei results in the data points of the much smaller ichnotaxa to concentrate on one side of the morphospace plot due to the larger overall footprint size and trackway dimensions, despite their significant differences. For example, Dongyangornipes is not significantly different from the Ignotornidae (psame = .132), Koreanaornipodidae (psame = .912), Tatarornipes (psame = .373), Uhangrichnus (psame = .635), and Avipedidae (psame = .900), despite the obvious visual differences between Dongyangornipes and the members of these ichnofamilies. Removing L. curriei from the ichnofamily analyses allows for a more accurate interpretation of the morphospace groupings among the remaining avian ichnotaxa. Canonical variate analyses with L. curriei removed still show strong statistical support for all analyzed ichnofamilies (Hotelling’s t-squared: psame <<< .01) (Fig. 15.3B); however, Morguiornipes (psame = .187) and Barrosopus (psame = .112) are not significantly different from the Avipedidae in this specific analysis.

Tridactyl and functionally tridactyl tracks

Avipedidae Due to the close association of Avipedidae and Koreanaornipodidae, the results of the analyses for both ichnofamilies will be discussed together (Fig. 15.4A, canonical variate graph; 15.4B, 15.4C, principle component analyses; and 15.4D, 15.4E discriminant analyses). The initial CVA of all of the ichnotaxa currently assigned to Avipedidae (Aquatilavipes izumiensis, A. swiboldae) with the ichnotaxa assigned to Koreanaornipodidae and the unassigned ichnogenera reveals the same results as the analyses that included all avian ichnotaxa: the inclusion of Limiavipes curriei (McCrea et al., 2014) skews the results by forcing the ichnogenera with smaller overall footprint size into a concentrated area of morphospace.

The CVA of the tridactyl tracks reveals interesting results. Tatarornipes chabuensis forms a discrete cluster in morphospace, save for one footprint of Koreanaornis dodsoni (Fig. 15.4A). T. chabuensis has a larger footprint width and digit III length relative to the other ichnotaxa in the analysis.2

Uhangrichnus chuni and Dongyangornipes sinensis are not significantly different (psame = .282), which is not surprising given their overall visual similarities (see “Ichnotaxonomic revision of Dongyangornipes sinensis”). However, the small sample size of D. sinensis prints in the data set may be also resulting in the nonsignificant differences seen both in the analysis of ichnofamilies (Fig. 15.3) and in the analysis of tridactyl prints only (Fig. 15.4A–15.4C). Aquatilavipes swiboldae and A. izumiensis show 100% overlap in morphospace despite a significant difference (psame = 9.87 × 10−03), whereas Koreanaornis hamanensis and K. dodsoni show 100% separation and are significantly different (psame = 6.26 × 10−19). However, A. swiboldae shows considerable overlap with Pullornipes, Morguiornipes, and K. dodsoni.

It is not unexpected that Aquatilavipes and Koreanaornis should occupy a similar morphospace: tracks of Aquatilavipes and Koreanaornis are not significantly different in footprint length (FL, t-test: psame = .86), or footprint splay (F/W ratio, t-test: psame = .56). However, tracks of Aquatilavipes and Koreanaornis do differ significantly in their total digit divarication (DIVTOT, t-test: psame = .02). Also, Aquatilavipes has not been reported with a preserved digit I (Currie, 1981; Azuma et al., 2002), whereas Koreanaornis hamanensis has been illustrated with a small, posteromedially oriented hallux (Lockley et al., 1992) (Figs. 15.1B, 15.1D). The combination of both qualitative and quantitative differences between Koreanaornis (small hallux and higher total divarication, respectively) and Aquatilavipes are enough to justify their separation as discrete ichnomorphotaxa, and the high degree of morphospace overlap between these two ichnogenera can easily be explained by their similarities in footprint length and digit splay. Discriminant analyses on Aquatilavipes and Koreanaornis reveal contradictory results. While the two groups are significantly different (psame = 9.80 × 10−04), the percentage of individual prints correctly assigned to their a priori groups was only 72.3% (Fig. 15.4D).

Principal component analysis on only Avipedidae and Koreanaornipodidae also provides equivocal results. The first principal component (size, 27.5%) does not reveal much information, except to group the ichnotaxa by size, with K. hamanensis being smaller (mean FL = 26.3 mm, n = 24) and K. dodsoni being larger (mean FL = 45.5 mm, n = 37) (Fig. 15.4B). Principal components two (PC2, divarication/digit splay ratio) and three (PC3, digit I length/DIV III–IV ratio) do little to differentiate the ichnotaxa in morphospace (Fig. 15.4C).

Avipedidae shows considerable overlap with the Koreanaornipodidae along PC1–PC2 in a PCA that includes all tridactyl ichnotaxa. There is a small separation seen between A. izumiensis and A. swiboldae along PC3 (PL and SL – digit lengths ratio): A. izumiensis has a slightly smaller mean footprint length (x = 37.7 mm) than A. swiboldae (x = 39.0 mm), although the difference is not significant (t-test: psame = .69). There is also a slight, although not significant (t-test: psame = .27), difference in total divarication between A. izumiensis (x = 120°, n = 17) and A. swiboldae (x = 114°, n = 20), which results in a separation along PC3 (digit splay – digit divarications ratio) (Figs. 15.4B, 15.4C).

Morguiornipes robusta is not shown to be significantly different from either ichnospecies of Aquatilavipes (A. izumiensis, psame = .544; A. swiboldae, psame = .744). Discriminant analyses comparing M. robusta to Aquatilavipes show that they are significantly different and have above 90% correct assignment to a priori categories (A. izumiensis: psame = 5.91 × 10−03, 100%; A. swiboldae: psame = .0241, 90.1%).

Koreanaornipodidae Canonical variate analysis on the ichnospecies within Koreanaornipodidae (Koreanaornis hamanensis, K. dodsoni, and Pullornipes aureus) and other tridactyl ichnospecies shows similar results to that of the CVA results of the Avipedidae. There is no overlap between K. hamanensis and K. dodsoni (Fig. 15.4A). Pullornipes aureus shows a small amount of morphospace overlap with K. dodsoni (psame = 3.11 × 10−15), and no overlap with K. hamanensis (psame = 3.78 × 10−22). Morguiornipes occupies almost the exact same morphospace as K. dodsoni does (psame = .610). Although there is neither statistical nor morphospace support for the separation of K. dodsoni and Morguiornipes, they are visually distinct. In discriminant analyses, Morguiornipes robusta is not significantly different from Koreanaornis dodsoni (psame = .0569), although 90.5% of prints were correctly identified (Fig. 15.4E). Also, Barrosopus and K. hamanensis occupy a similar morphospace and are not significantly different (psame = .092) (Fig. 15.4A) despite visual differences. (See “Avipedidae” for detailed results of the comparison between Avipedidae and Koreanaornipodidae.)

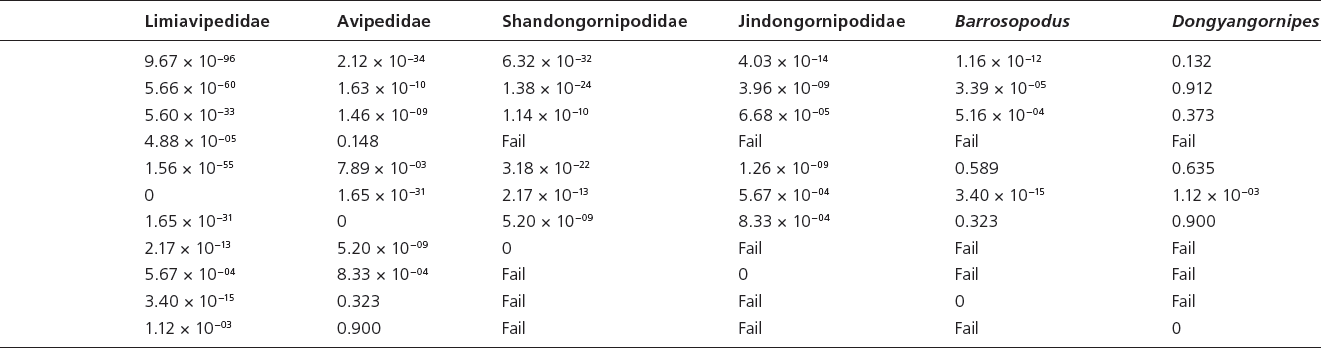

15.5. (A) Canonical variate analysis of tetradactyl Mesozoic avian ichnites and the unassigned avian ichnotaxa (Uhangrichnus, Dongyangornipes, Barrosopus, Morguiornipes, Tatarornipes). Shandongornipes muxiai and Jindongornipes kimi form discrete groups, whereas the ignotornids separate into the I. mcconnelli –I. yangi–Goseongornipes, and the Hwangsanipes–I. gajiensis groups. (B) Principal component (PC) analysis graphical results of the tetradactyl Mesozoic avian ichnotaxa and the unassigned avian ichnotaxa. PC1 represents data related to digit I, whereas PC2 represents the footprint and trackway size data/divarication ratio. As in Figure 15.6A, Ignotornis mcconnelli and I. yangi cluster together. This grouping is due to similarities in divarications and footprint size, specifically having a relatively larger DIV I–II with a smaller foot and pace and stride. Shandongornipes muxiai forms a discrete cluster due to the relatively larger divarications between digits I and II and total divarication. (C) Principal component analysis graphical results of the tetradactyl Mesozoic avian ichnotaxa and the unassigned avian ichnotaxa with PC1 (relative size of digit I) removed. The PC2 axis represents digit I placement-/footprint size ratio, and PC3 represents trackway size/trackway width ratio. The groupings show more overlap, but as in Figures 15.6A and 15.6B, Ignotornis mcconnelli and I. yangi cluster together. Abbreviations: DI, digit I; other abbreviations as in Figure 15.2.

Tetradactyl avian tracks

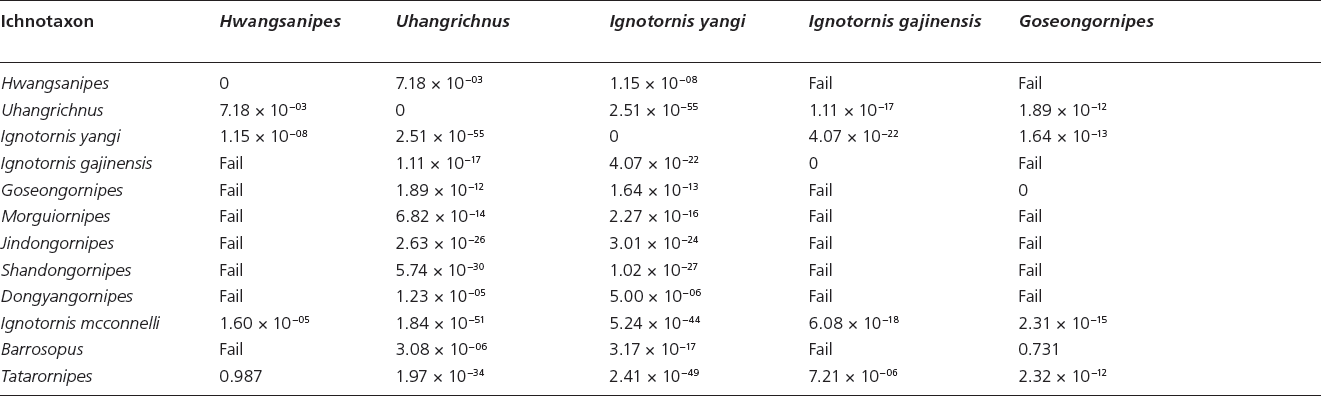

Ignotornidae The individual ichnogenera within the Ignotornidae (Ignotornis, Hwangsanipes, Goseongornipes) occupy the same morphospace, although Hwangsanipes and Goseongornipes occupy the outer edges of the Ignotornis morphospace (Figs. 15.1C and 15.5; Table 15.4). Canonical variate analysis of the ichnospecies within the ichnofamily Ignotornidae analyzed with avian ichnotaxa currently not assigned to an ichnofamily reveals that, despite the strong statistical support for all of the individual ichnofamilies, there is a strong grouping in morphospace for Ignotornis mcconnelli, I. yangi, and Goseongornipes markjonesi (Fig. 15.5A). However, I. gajinensis does not occupy a similar morphospace to that of I. mcconnelli, I. yangi, and G. markjonesi (and is significantly different from these ichnospecies) but occupies a similar morphospace for Hwangsanipes (Ignotornidae) and Tatarornipes (ichnofamily unassigned) (Fig. 15.5A). A principal component analysis performed on these ichnotaxa reveals that the main quantitative difference between the I. gajinensis – Hwangsanipes group and the Ignotornis-Goseongornipes group is the size of digit I: the Ignotornis-Goseongornipes group has a longer digit I, as presented in the PCA morphospace plot (Fig. 15.5B, 15.5C).

Given the morphologic similarity between Ignotornis and Jindongornipes, it was expected that the two ichnogenera would occupy a similar morphospace: both ichnogenera have a well-defined digit I, digits II and IV have wide angles of divarication from digit III, and some indication of webbing between digits III and IV. One issue that affects the analysis of Jindongornipes is that there are only two data points made available from the systematic description of J. kimi. However, based on the available data, the Ignotornidae and Jindongornipes are significantly different based on DA (psame = 2.97 × 10-−17). The Ignotornidae are smaller, have a longer digit I relative to footprint length and a higher digit divarication between digits I and II, whereas Jindongornipes has a relatively higher divarication between digits II and III (Fig. 15.5). The results of this analysis could be greatly altered by the inclusion of more data.

Shandongornipodidae There is both strong qualitative and quantitative support for the ichnofamily Shandongornipodidae. Shandongornipes muxiai is the only described trackway of a zygodactyl trackmaker from the Mesozoic: the unique positioning and splay of the digits makes this ichnotaxon easily distinguishable from other described Mesozoic avian ichnotaxa. In CVA, S. muxiai forms a discrete cluster in morphospace (Fig. 15.5A, with the exception of one track that contained a large amount of missing data, which groups with I. mcconnelli). Principal component analysis reveals that S. muxiai is distinguished from the other tetradactyl avian ichnotaxa by the footprint length including the length of digit I along PC1 (footprint size–trackway dimensions ratio) (Fig. 15.5B). When size (PC1, 19.5% of total variation) is removed, S. muxiai groups with the tetradactyl ichnotaxa possessing a relatively large digit I and a high digit divarication DIV III–IV (PC2, 17.4% of total data set variation) (Fig. 15.5C).

Jindongornipodidae The avian ichnofamily Jindongornipodidae is represented only by one ichnospecies, Jindongornipes kimi. Other than the observations made when compared to the Ignotornidae, the amount of footprint and trackway data available in the literature for these analyses (n = 2) caused many of the analyses to fail. However, with the data available, J. kimi does form a discrete group in the CVA.

Avian ichnospecies currently unassigned to ichnofamilies

Tatarornipes chabuensis In the analyses of tridactyl ichnotaxa, Tatarornipes chabuensis forms a discrete cluster from the Avipedidae, the Koreanaornipodidae, and the unassigned ichnospecies. The qualitative assignment to a discrete ichnospecies is justified statistically (psame <<< .01). Tatarornipes is separated from the rest of the tridactyl ichnotaxa by its relatively large footprint width and digit III length (Fig. 15.4).

Table 15.4. Canonical variate analysis results of log10-transformed linear and unadjusted angle data (App. 15.1) of tetradactyl Mesozoic avian ichnotaxa a priori assigned to current ichnospecies and those Mesozoic avian ichnotaxa currently unattributed to ichnofamilies.

Note: “Fail” indicates a priori groups for which too few data were available for statistical analysis.

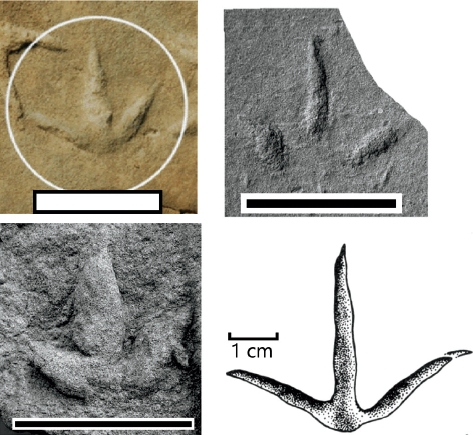

Morguiornipes robusta As described in the results of the Avipedidae and Koreanaornipodidae analyses, Morguiornipes robusta is not statistically different from Aquatilavipes izumiensis, A. swiboldae, and Koreanaornis dodsoni. Principal component analysis shows that M. robusta groups with the individual tracks of A. swiboldae, K. hamanensis, K. dodsoni, and Barrosopus slobodai with similar digit lengths (App. 15.1). However, this grouping is due to similarity in variables: M. robusta is qualitatively distinct from Koreanaornis and Aquatilavipes in that it has much thicker (or wider) digits than the two aforementioned ichnogenera. The thickness of the digits is reminiscent of that observed in Tatarornipes chabuensis, but the digits of M. robusta do not taper sharply distally as the digits do in T. chabuensis (Fig. 15.6).

Barrosopus slobodai Prints of Barrosopus slobodai are not significantly different from Aquatilavipes izumiensis, A. swiboldae, or Koreanaornis hamanensis (Fig. 15.4A, Table 15.3). Discriminant analysis confirms the quantitative similarities of B. slobodai and A. swiboldae (psame = .831, 76.7% correctly identified), A. izumiensis (psame = .403, 73.1% correctly identified), and K. hamanensis (psame = .755, 82.9% correctly identified). Barrosopus and K. hamanensis occupy a similar morphospace due to shared characteristics in overall footprint and trackway dimensions: they do not significantly differ in total divarication (t-test: psame = .50), pace length (t-test: psame = .12), or digit splay (FL/FW, t-test: psame = .087).

Avian Ichnites versus Small Nonavian Theropod Ichnites (Magnoavipes)

Magnoavipes is a contentious ichnogenus: the relatively large size, with footprint lengths approaching 200 mm or more (App. 15.1) is indicative of a small theropod trackmaker, whereas its high divarication (M. lowi = 110°, M. caneeli = 85.1°, M. denaliensis = 107°) suggests a trackmaker of avian affinity (Table 15.2). Divarication and trackway data were analyzed separately on Mesozoic avians, Magnoavipes, and Early Cretaceous theropods (ntotal = 59; McCrea, 2000) to determine the diagnostic strength of total divarication and trackway data for distinguishing between bird and theropod ichnites.

First, using total divarication as a discriminatory tool between theropod and avian tracks holds when using t-tests of means: comparing the means of the total divarication of theropods (Irenichnites, Irenisauripus, Columbosauripus, and an unidentified small theropod; mean = 87.8°, n = 26) and tracks of semipalmate avians (Aquatilavipes, Koreanaornis, Tatarornipes, Morguiornipes; mean = 111°, n = 202) does show a significant difference (psame = 5.40 × 10−08). However, the range of data shows a considerable amount of overlap (Table 15.2). The total divarication of Magnoavipes is not significantly different than that of the theropod sample (t-test: psame = .245), but the total divarication of Magnoavipes is significantly different than that of the semipalmate avians (t-test: psame = 7.23 × 10−05).

Discriminant analyses on DIV II–III, DIV III–IV, and DIVTOT confirm the univariate statistical results. Magnoavipes is not significantly different than the sampled theropods (psame = .179, 67.8% correctly identified). Magnoavipes is significantly different than the avian sample (psame = 1.37 × 10−03, 71.3% correctly identified), and the theropod sample was significantly different than the avian sample (psame = 2.79 × 10−04, 67.8% correctly identified). In all three DA, there was difficulty in correctly assigning each print to its a priori ichnotaxon. This is likely due to the large amount of variation in digit divarication of both birds and theropods: theropod tracks can reach total divarications of 120°, and bird tracks can exhibit total divarications as low as 60° (Table 15.2; App. 15.1). There is no one divarication value that clearly separates bird from theropod tracks.

Because of the great disparity in size between the tracks attributed to birds and those attributed to theropods and the ichnogenus Magnoavipes, the CVA comparing these ichnotaxonomic groups was performed on log10-transformed linear data and unaltered angle data. The results show that all three groups are significantly different, but there is a great deal of overlap among the three groups (Fig. 15.7A). Although the largest amount of relative variation occurs along the footprint data – trackway data axis, in morphospace there is very little separation among the three ichnotaxonomic groups along this axis.

In order to determine whether footprint ratios could be used to discriminate between the tracks of birds (including Limiavipes curriei) and theropods (and to remove size as a factor in the analyses), the footprint ratios were analyzed using CVA. Even though birds, Magnoavipes, and theropods were all significantly different from one another, they all occupy the same morphospace. The only indication of any ichnotaxonomic grouping was that tracks of Magnoavipes occupy almost the same morphospace as that occupied by tracks of the theropod sample (Fig. 15.7B). It is evident that the footprint data alone (save for size) is not sufficient to separate the tracks of theropods from those of birds in a multivariate analysis.

Trackway data (pace and stride length, pace angulation, and footprint rotation) were analyzed using CVA, and the results show that both theropods (psame = 1.66 × 10−31) and Magnoavipes (psame = 1.94 × 10−27) are significantly different from birds, whereas the prints of Magnoavipes are not significantly different from prints of theropods (psame = .987). However, these differences are largely size-based, so the same analysis was run using log10-transformed pace and stride lengths. The results are similar: both theropods (psame = 9.84 × 10−35) and Magnoavipes (psame = 7.27 × 10−20) (Fig. 15.7C) are significantly different from the trackways of birds. These results are supported by the bivariate statistics: log10-pace lengths are significantly different between theropod and bird trackways (psame = 1.68 × 10−6), and between bird trackways and the trackways of Magnoavipes (psame = 2.00 × 10−03), whereas the difference between the log10-pace lengths of Magnoavipes and theropod trackways is significant at p ≥ .05 but not at p ≥ .01 (psame = .014).3

ICHNOTAXONOMIC REVISION OF DONGYANGORNIPES SINENSIS

Uhangrichnus chuni was established by Yang et al. (1995) and was the first described functionally tridactyl, palmate avian track. The description of U. chuni was emended by Lockley, Lim, et al. (2012) based on the description by Lockley and Harris (2010) of a topotype specimen of U. chuni with a short, posteromedially directed hallux. However, the emended diagnosis states that “web configuration palmate (i.e., well-developed) and equally developed in hypices between digits II and III and III and IV” (Lockley, Lim, et al., 2012:20). This is different than the webbing reported for Dongyangornipes sinensis (Azuma et al., 2013:5), stating: “although similar to U. chuni in size and general morphological characteristics, Dongyangornipes sinensis differs in that the anterior margin of the web impression is connected from the apex of digit III to the apex of digits II and IV in U. chuni,” and “the web impression between II and III is connected from the apex of digit II to the posterior third of digit III, whereas the web impression between digits III and IV is linked from the apex of digit IV to the middle of digit III.”

15.6. Functionally tridactyl Mesozoic avian footprints: (upper left) Tatarornipes chabuensis (Lockley, Li, et al., 2012); (upper right) Koreanaornis dodsoni (Xing et al., 2011); (lower left) Morguiornipes robusta (Xing et al., 2011); (lower right) Aquatilavipes swiboldae (Currie, 1981). Despite their morphologic differences, these four ichnotaxa tend to group together in multivariate statistical analyses due to the similarity in their measured variables. Collecting the variable of digit width might cause these groups to separate in morphospace. Scale = 5.0 cm.

We now consider these differences in webbing to be more parsimoniously explained by preservational variation: it is not uncommon for webbed tracks of one trackmaker to present a variety of webbing conditions. Several of the tracks of Uhangrichnus chuni pictured in figure 5 of Yang et al. (1995) display the webbing conditions (connected at the apices of digits II and IV and connecting on the posterior third and middle of digit III, respectively; asymmetrical web impressions) described as unique to Dongyangornipes sinensis and that separate D. sinensis from U. chuni. Also, the tracks of U. chuni and D. sinensis are similar in size, as noted by Azuma et al. (2013): the average (presumably) D. sinensis is described as footprint length of 3.64 cm and footprint width of 3.96 cm. This falls within the size range reported for U. chuni (FL: 3.30–4.62 cm, average 3.70 cm; FW: 3.8–5.4 cm, average 4.58 cm). The only quantitative difference between U. chuni and D. sinensis is that of footprint splay, as represented by total (II–IV) divarication and FL/FW. U. chuni has a wider splay (L/W: 0.81, total divarication 110°) than D. sinensis does (L/W: 0.87, total divarication 100°); however, given the small sample size of D. sinensis compared to that of U. chuni, there are prints of U. chuni that also exhibit the same footprint splay seen in D. sinensis.

Given that the unique webbing characteristic of Dongyangornipes reported by Azuma et al. (2013) to separate Uhangrichnus from Dongyangornipes is also observed (if not reported) in the original description of Uhangrichnus, and that the sample size of Dongyangornipes is reasonably too small to preserve a sporadically preserved hallux, we feel that there is very little to visually differentiate Uhangrichnus and Dongyangornipes. We consider Dongyangornipes sinensis a subjective junior synonym of Uhangrichnus chuni.

15.7. (A) Canonical variate analysis on log10-transformed footprint and trackway data of a priori separated groups of Magnoavipes, Mesozoic tridactyl semipalmate avians, and Early Cretaceous theropods (Irenisauripus, Irenichnites, Columbosauripus, and one unidentified small theropod ichnite). There is a large amount of overlap among the three groups, and a slight separation of the Magnoavipes and theropod groups along the footprint size axis. Both Magnoavipes and the theropods occupy a close, but not overlapping, section of morphospace. (B) Canonical variate analysis on footprint measurement ratios (FL/FW, DL2/DL3, DL4/DL3) of Magnoavipes, Mesozoic tridactyl semipalmate avians, and Early Cretaceous theropods (Irenisauripus, Irenichnites, Columbosauripus, and one unidentified small theropod ichnite). The footprint ratios used in this analysis did not provide any for separating theropod ichnites from bird ichnites, but they did show that theropods, because of the narrower splay on their digits, have a relatively larger FL/FW. All a priori groups are significantly different from one another. (C) Canonical variate analysis on log10-tranformed pace (PL) and stride (SL) data, footprint rotation (FR), pace angulation (PA), and footprint length/footprint width ratios (FL/FW) of Magnoavipes, Mesozoic tridactyl semipalmate avians, and Early Cretaceous theropods (Irenisauripus, Irenichnites, Columbosauripus, and one unidentified small theropod ichnite). Birds have a relatively larger pace angulation and footprint rotation, whereas Magnoavipes and theropods have a relatively larger FL/FW. Magnoavipes and bird trackway data are significant (psame = 2.00 × 10−03), whereas Magnoavipes and theropod trackway data are significant at p ≥ .05 but not at p ≥ .01 (psame = .014).

Systematics

Class Aves

Ichnofamily indet.

Uhangrichnus chuni (Yang et al., 1995;

emend. Lockley, Lim, et al., 2012)

Referred material

Chun, 1990:10a

“tracks of a bird with webbed feet”

Lockley et al., 1992:figure 9

Uhangrichnus chuni Yang et al., 1995:figure 5

Uhangrichnus chuni Yang et al., 1997:figures 3–5

Uhangrichnus chuni Lockley &

Rainforth, 2002:figure 17.12B

Uhangrichnus chuni Kim et al., 2006: figure 3D

Uhangrichnus chuni Lockley, 2007:figure 1D

Uhangrichnus chuni Lockley &

Matsukawa, 2009:figure 15D

Uhangrichnus Lockley & Harris, 2010:figure 9C

Dongyangornipes sinensis Azuma et al., 2013

Emended diagnosis Small, functionally tridactyl tracks of a web-footed bird with small, posteromedially directed hallux trace are sporadically preserved. Web configuration palmate, with the posterior margins of the webbing ranging from equally developed between digits II and III and digits III and IV, to connecting at the middle to the posterior third of digit III. Footprint, excluding hallux, wider (W) than long (L), averaging 3.70 and 4.58 cm, respectively (L/W = 0.81), but footprint length with hallux slightly longer than wide (L/W = 1.1). Trackway narrow with short step and stride (7.8 and 15.7 cm, respectively) and strong inward rotation (mean 20°) of digit III relative to trackway midline.

DISCUSSION

Qualitative Ichnotaxonomic Assignments of Avian Ichnotaxa Have Statistical Support

Multivariate statistical analyses have been shown to be a useful tool in testing the qualitative ichnotaxonomic assignments of avian ichnotaxa. These qualitative assignments, for the most part, are well-supported statistically. Although taxonomic assignments of ichnology specimens have received some criticism for being too subject to preservation and substrate consistency, the strong statistical support for the current standing avian ichnotaxa demonstrates that the assignment of vertebrate ichnotaxa is not random: the qualitative and simple quantitative differences observed in Mesozoic avian ichnotaxa have strong quantitative support.

Separating Tracks of Large Avians from Small Theropods

Save for size, there is a great deal of overlap in the track morphology data of small theropods and large avians. The multivariate statistical analyses support the assignment of the ichnogenus Magnoavipes to a theropod, rather than an avian, trackmaker by Lockley, Wright, and Matsukawa (2001). The strongest support came from the trackway data: for all of the avian characteristics of the tracks of Magnoavipes (high total divarication, narrow digit widths; Lee, 1997), the data suggest that the trackmaker of Magnoavipes walks more like a theropod than a bird. The difference in pace angulation and footprint rotation between theropods and avians has long been observed: trackways attributed to theropods have higher angles in pace angulation (footprints placed closer to the midline of the trackway) and lower footprint rotation (footprints closer to parallel with the midline of the trackway) (Lockley, Wright, and Matsukawa, 2001).

Also, total divarication (DIV II–IV, as used in the original description of Magnoavipes, Lee, 1997) is unreliable for separating bird tracks from theropod tracks, and there is a large amount of overlap in the range of total divarications exhibited by Mesozoic avian ichnites and those of Early Cretaceous theropod ichnites (Table 15.2). Also, digit divarication can vary considerably within a single trackway in both avians and theropods (App. 15.1). Determining the affinity of a trackmaker based largely on the average total divarication is arbitrary and ignores both extant avian track data and fossil data for tracks of both theropods and avians alike. Given that both extant and extinct shorebirds are capable of such relative extremes in digit divarication, ichnologists must accept that Mesozoic analogues to extant shorebirds were likely capable of such relative extremes in digit divarication as well.

Trackways ratios, using the most common data collected for both avian and theropod tracks (footprint length; footprint width; digit lengths II, III, and IV; digit divarications) have the benefit of removing absolute size from the analyses but do not contain enough data to discriminate between avian and theropod tracks. Analyzed together, the number of measured footprint parameters outnumbers the trackway parameters, which may account for the lack of separation in morphospace between birds and theropods.

Multivariate Statistical Analyses Are Not a Primary Tool for Ichnotaxonomic Assignment

While multivariate statistical analyses are a useful tool for testing previously established ichnotaxonomic assignments, and are also useful to test the quantitative support of the systematic assignment of future avian ichnotaxa, multivariate statistical analyses should not be used as the sole tool in either assigning an ichnite to an ichnotaxon or as the sole means of identifying the potential trackmaker of one footprint. Statistics, whether they be bivariate or multivariate, are best in a supporting role in vertebrate ichnology rather than as the primary source of interpretations.

Criticisms of using multivariate analyses as the sole means of identifying the trackmaker of an ichnite have been discussed in length by Thulborn (2013) in his analysis of the reinterpretation of the large tridactyl trackmaker in the famous Lark Quarry track site (Romilio and Salisbury, 2011). Many of these criticisms are valid: one cannot use a multivariate statistically determined “cut-off” value between two groups with any morphologic similarity to determine the accurate placement of single ichnites, or even single trackways (Thulborn, 2013). Statistically determined threshold values used to either assign previously unassigned ichnites to existing ichnotaxa or to determine trackmaker affinity are only as accurate as the degree of separation between the samples used to create the threshold value. The analyses are subject to the initial a priori assignments of the researchers. Any threshold value established between two groups with less than 100% separation will be inaccurate depending on the amount of morphologic overlap between the two groups: the more overlap, the greater the inaccuracy of the identification of the ichnite using the threshold.

Recommendations for Future Data Collection and Data Reporting

Multivariate statistical analyses are only as accurate as the data used within the analyses. The analyses herein would have been greatly improved had data been reported for all of the track and trackway variables. This is not referring to the missing data that is inherent in so many vertebrate ichnology data sets: data cannot be reported for prints that are incompletely preserved. Data should, however, be collected for all footprint and trackway variables that can be measured, even if they do not immediately aid in the systematic classification of the ichnite in question. Depending on the nature of the avian ichnites, all data variables may not be available to collect. For example, Aquatilavipes swiboldae (Currie, 1981) and Uhangrichnus chuni (Yang et al., 1995) were described from specimens where individual trackways were difficult to discern, making the accurate collection of trackway data unfeasible. However, where feasible, thorough footprint and trackway data should be both collected and reported.

Reexaminations of avian ichnotaxa for which the original descriptions did not supply a large amount of data (either due to the original paucity of specimens at the time of description or lack of publishing the originally collected data), such as the reexamination of Ignotornis mcconnelli by Lockley et al. (2009), are extremely important to the study of avian ichnotaxonomy. As more specimens of existing avian ichnotaxa are recovered, such reexaminations of existing avian ichnotaxa will be beneficial for further resolving avian diversity in the Mesozoic.

CONCLUSIONS

This is not the final statistical review of Mesozoic avian ichnotaxonomy. As more specimens of existing avian ichnotaxa are recovered, and as novel avian ichnotaxa are erected, the results herein will undoubtedly be refined. The analyses herein do reveal useful information in demonstrating that the valid Mesozoic avian ichnotaxa have strong statistical support. These analyses also demonstrate that ichnotaxa erected using qualitative observations on size, shape, and basic statistical data are not arbitrarily named shapes. Ichnotaxonomy is a discipline that will continue to draw heavily on qualitative information, and thus far qualitative information has proved reliable. However, with the development of new data collection technologies, useful quantitative data can be used to support the qualitative observations.

To aid in the future quantitative analyses of vertebrate ichnites, we offer the following recommendations:

1. A reanalysis of the existing avian ichnotaxa, in the manner of Lockley et al. (2009), to amend the previously published data sets;

2. Collect and publish as many track and trackway variables as is feasible for each specimen. It is not enough to merely report averages of novel ichnotaxa; all data should be made available for more accurate comparisons and future statistical analyses;

3. As potentially useful as multivariate statistical analyses are, the utility of such analyses in resolving contentious ichnotaxonomic assignments or providing information to support a novel ichnotaxonomic assignment will only be as accurate as the input data.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We wish to first thank the researchers who collected and published the data used in this statistical review. We also wish to thank J. Milàn, an anonymous reviewer, and A. Richter for their helpful reviews of the manuscript.

NOTES

1. Even though ichnotaxonomy is the focus of this study, this caveat is applicable to all morphotaxa used in multivariate statistical analyses.

2. One of the diagnostic characteristics of Tatarornipes chabuensis is the robust width of the proximal digits (Lockley, Li, et al., 2012). Digit width is not a variable that is often reported in avian tracks: one exception is Azuma et al. (2013), who report digit width in their description of Dongyangornipes sinensis. Due to the large amount of missing data that digit width would have introduced to the analyses, digit width was not included.

3. Note in proof: since the production of this manuscript, two studies have been submitted for publication (Xing et al., 2015; Buckley et al., 2015) which detail new metrics and considerations for distinguishing between the tracks of large avians and those of small nonavian theropods.

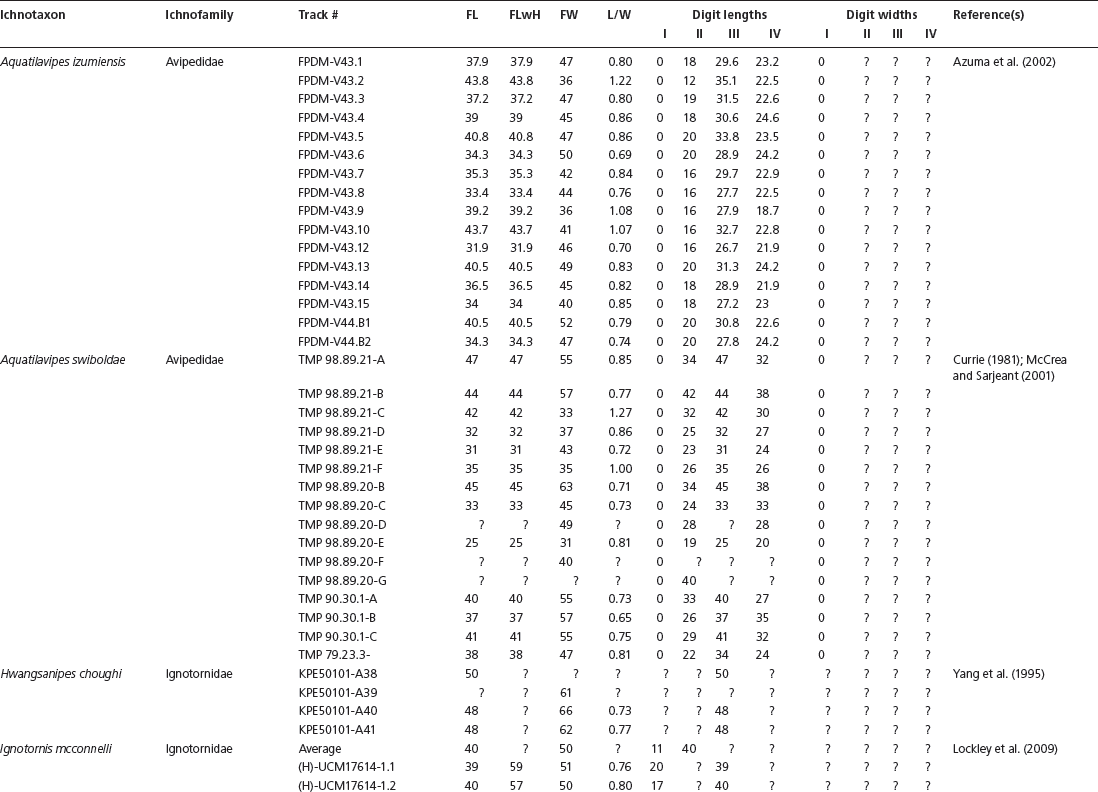

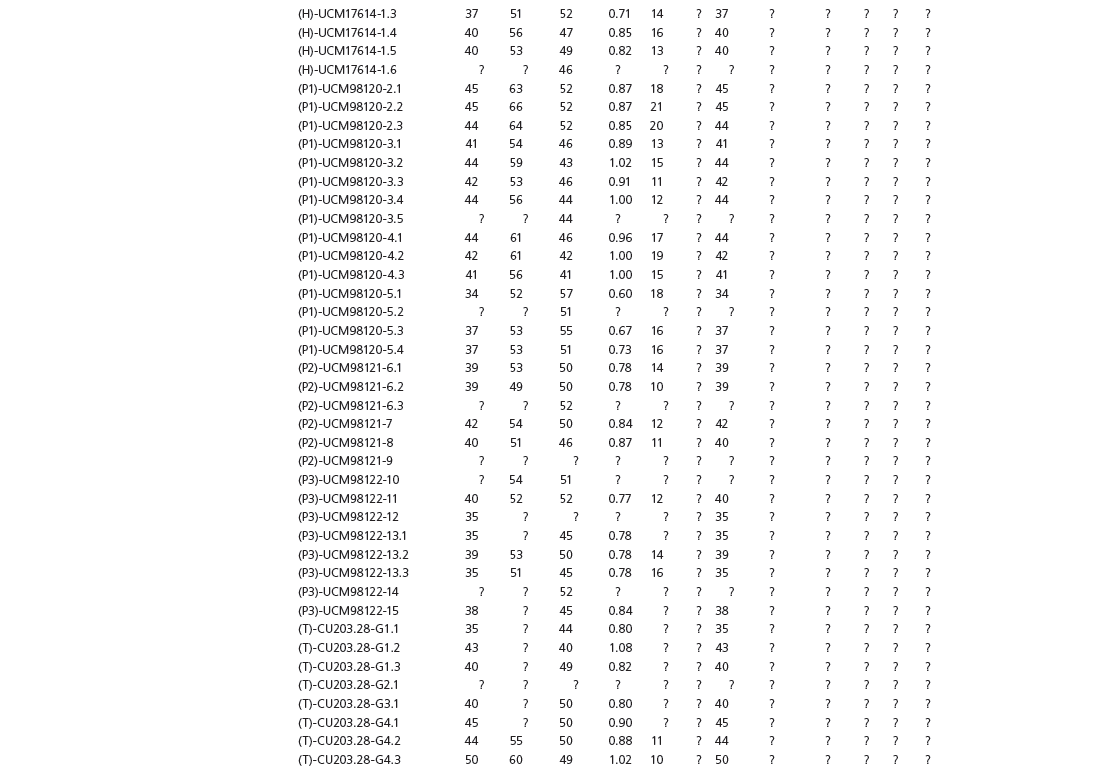

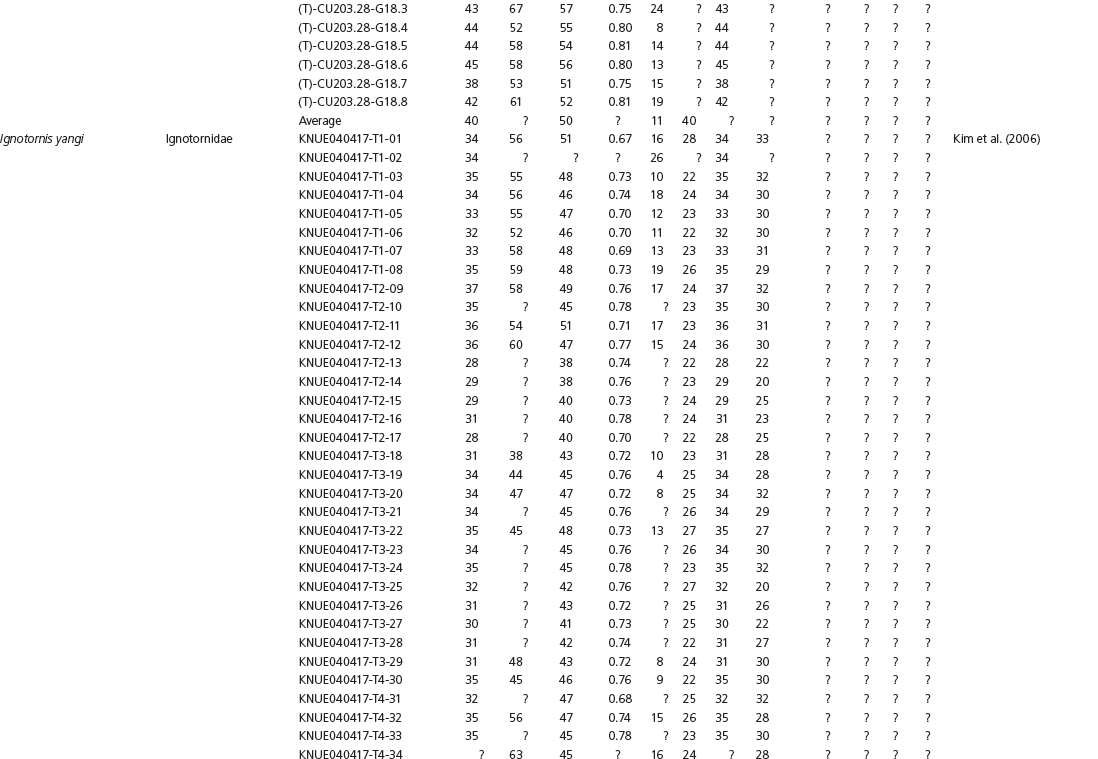

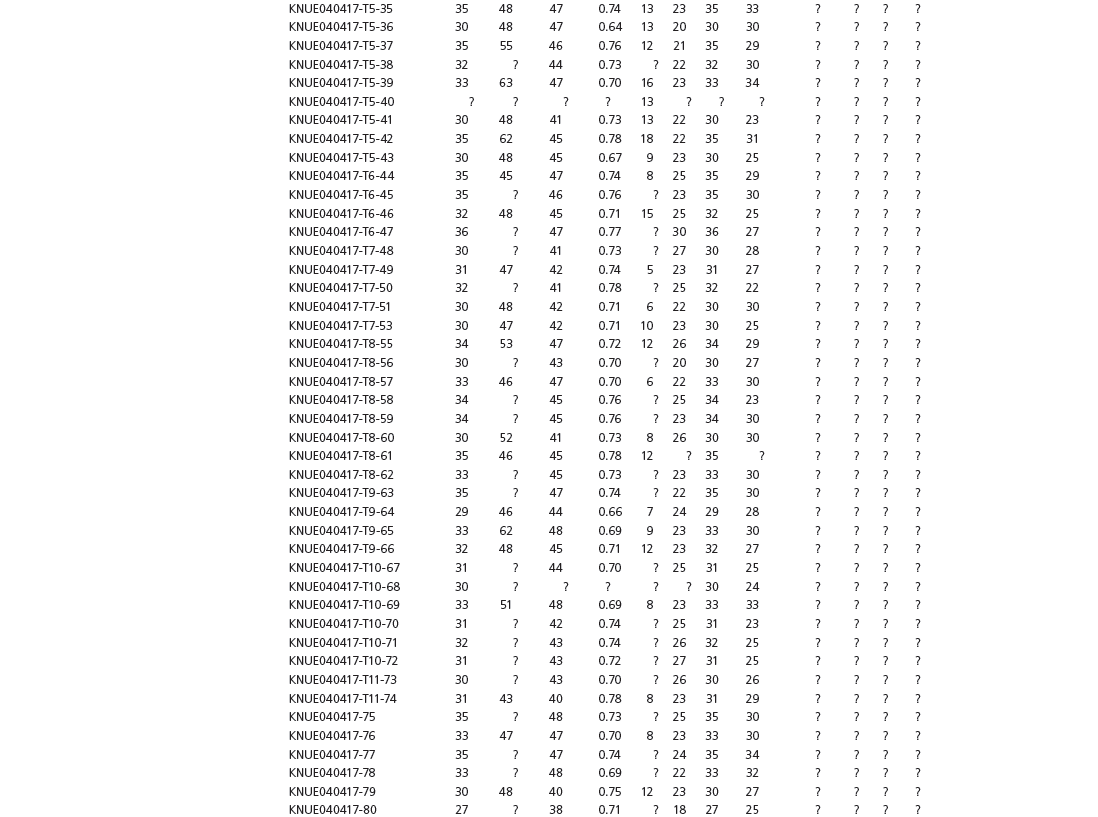

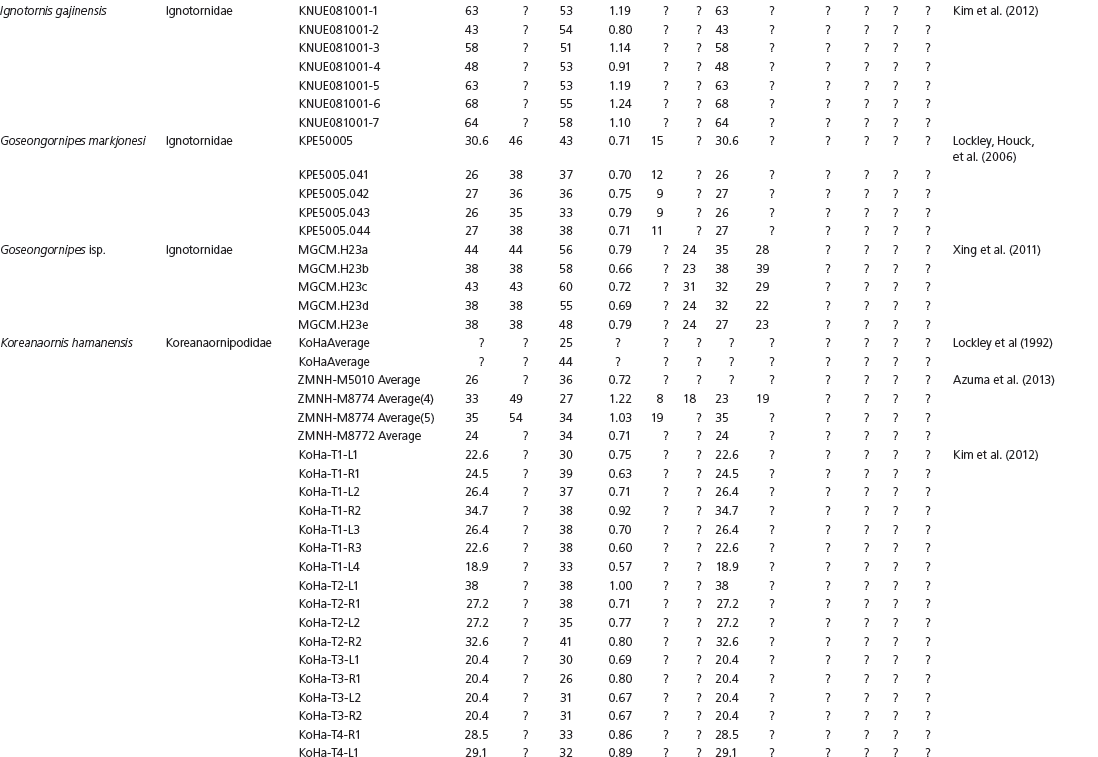

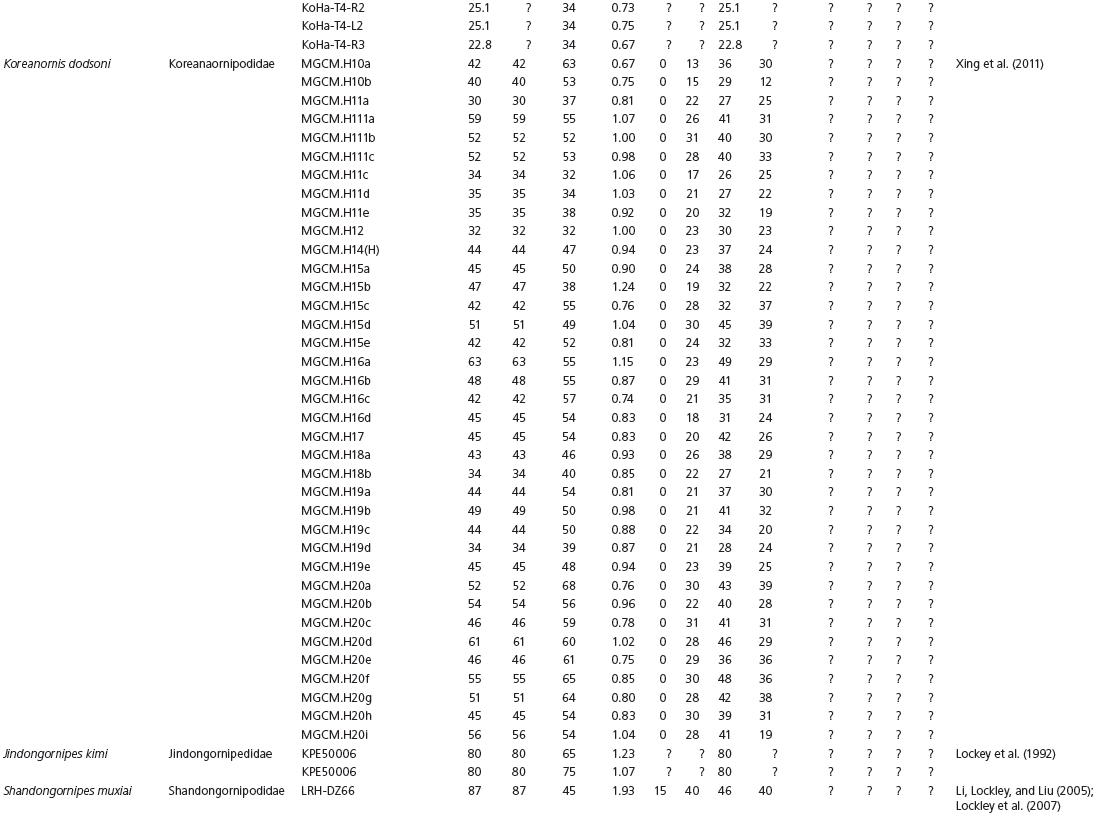

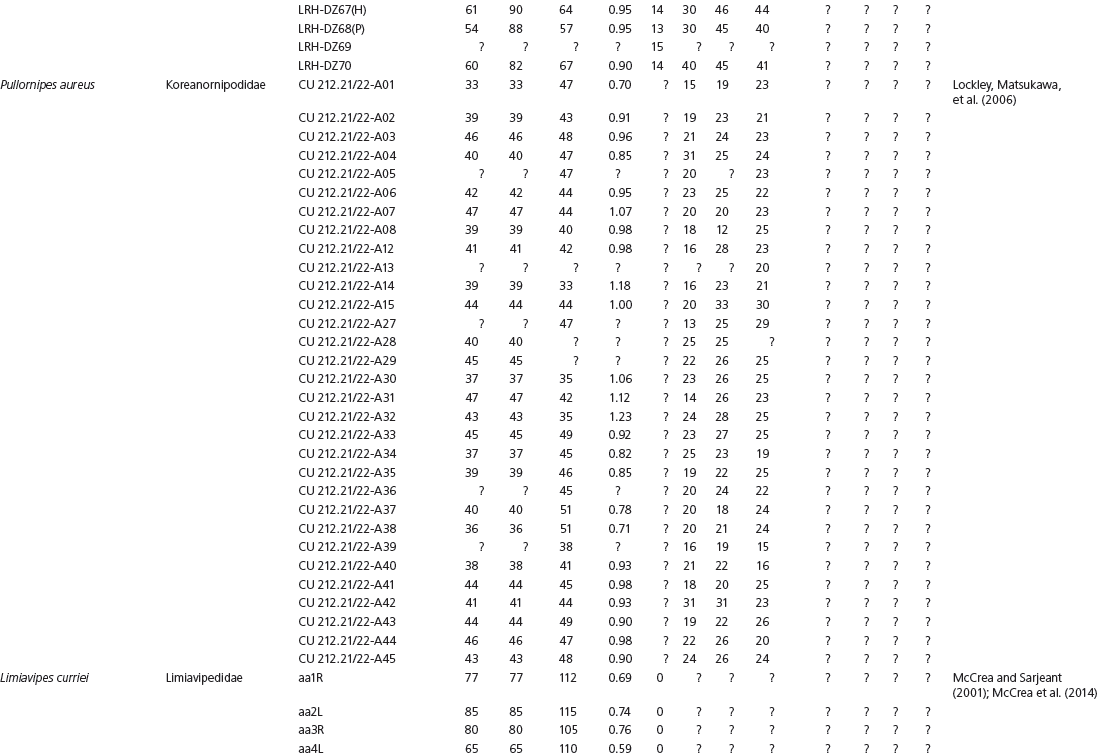

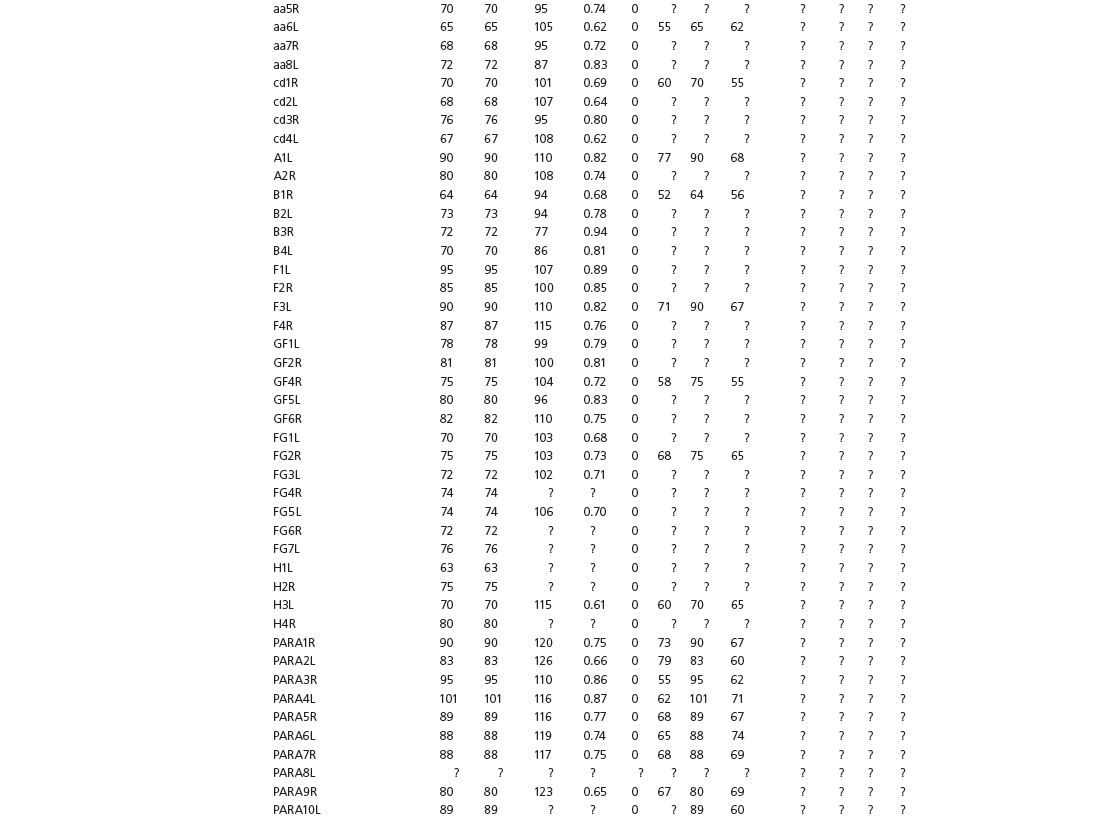

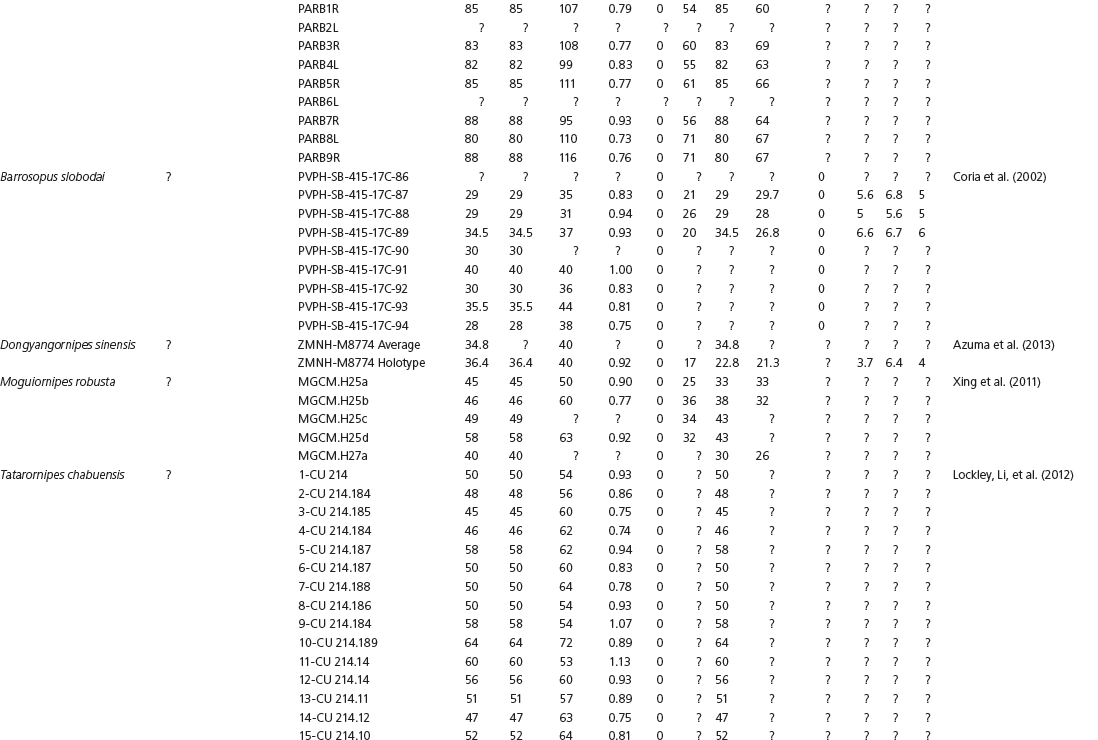

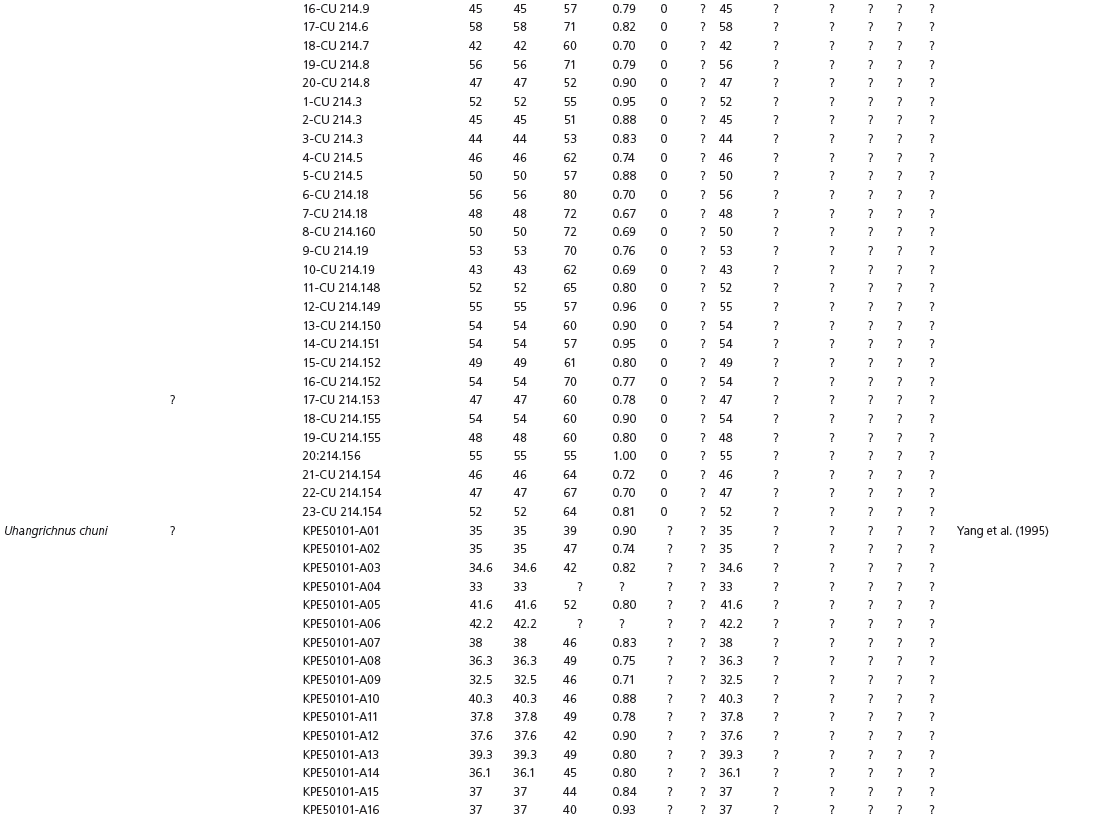

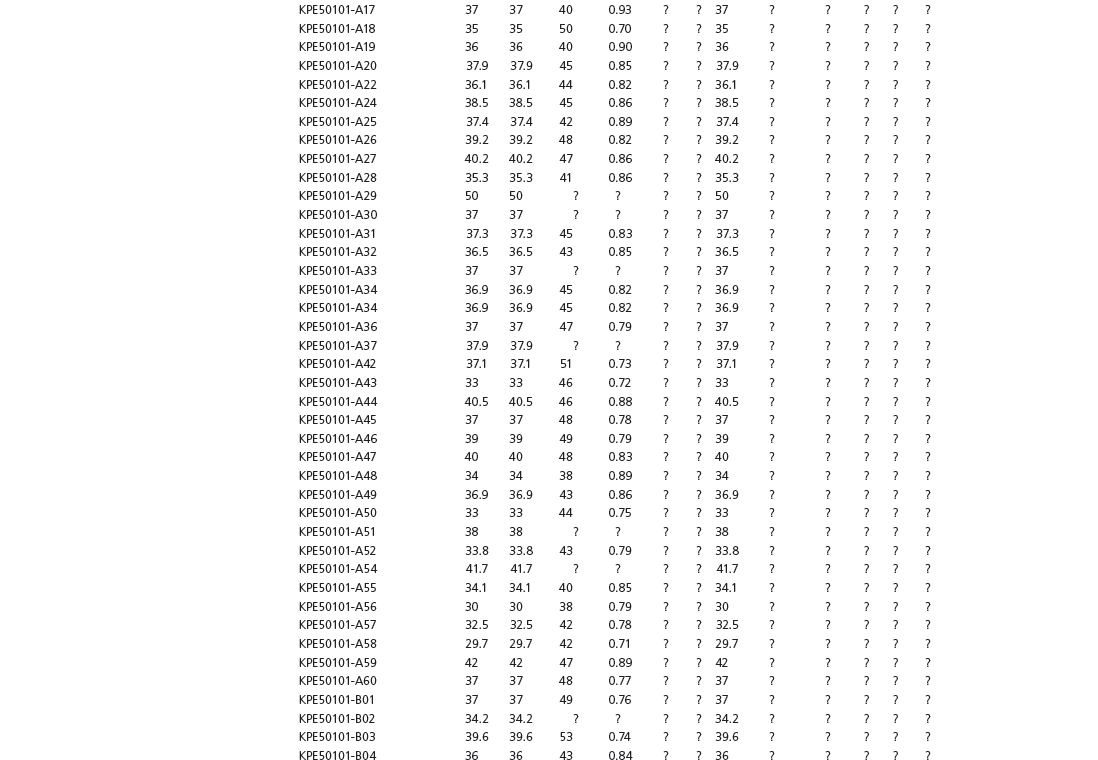

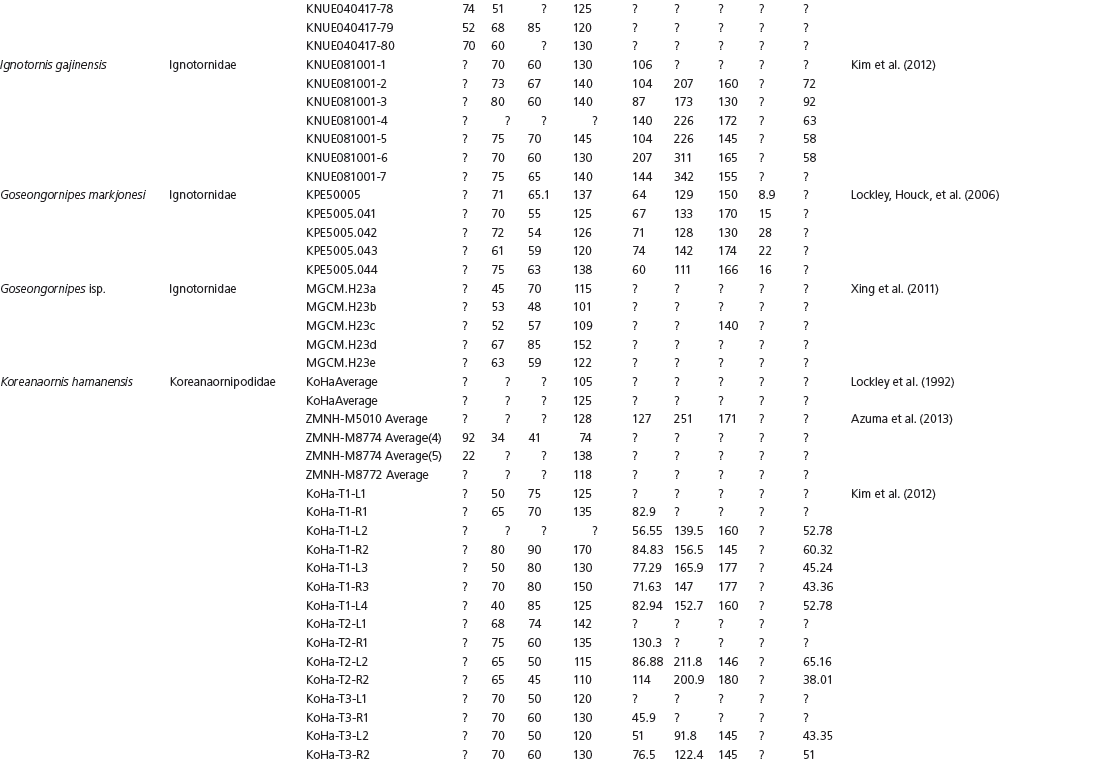

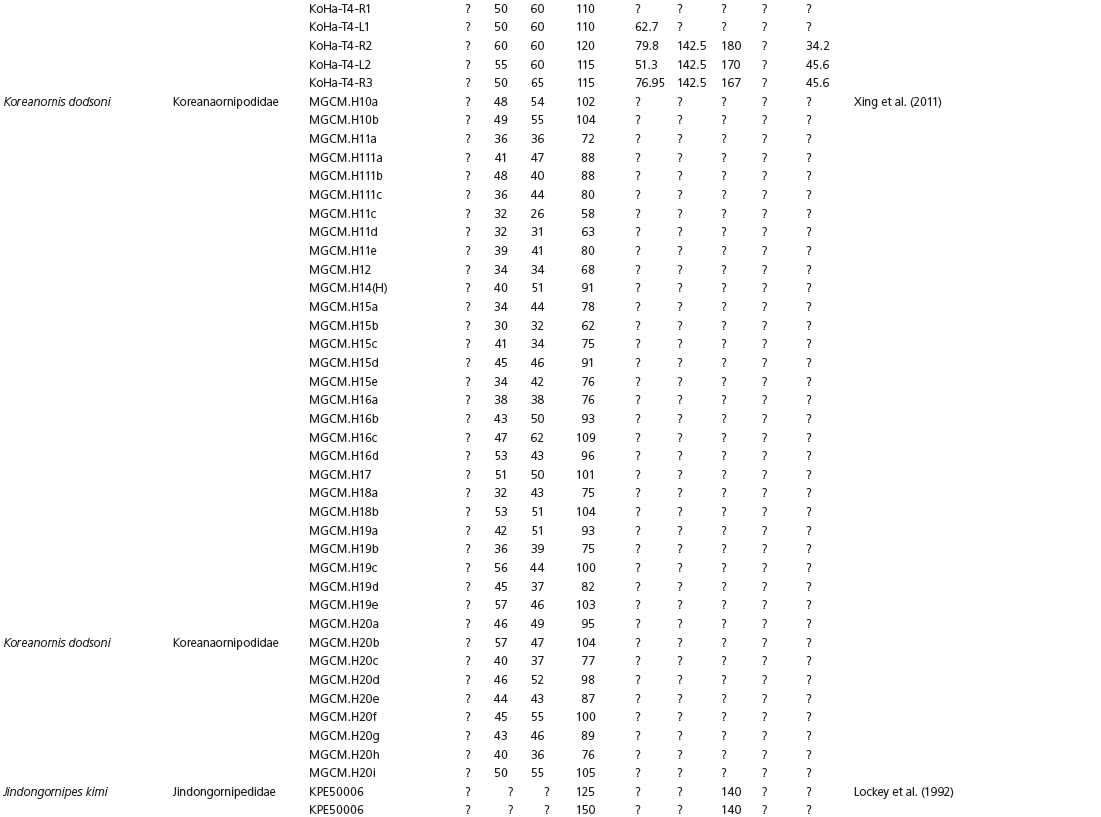

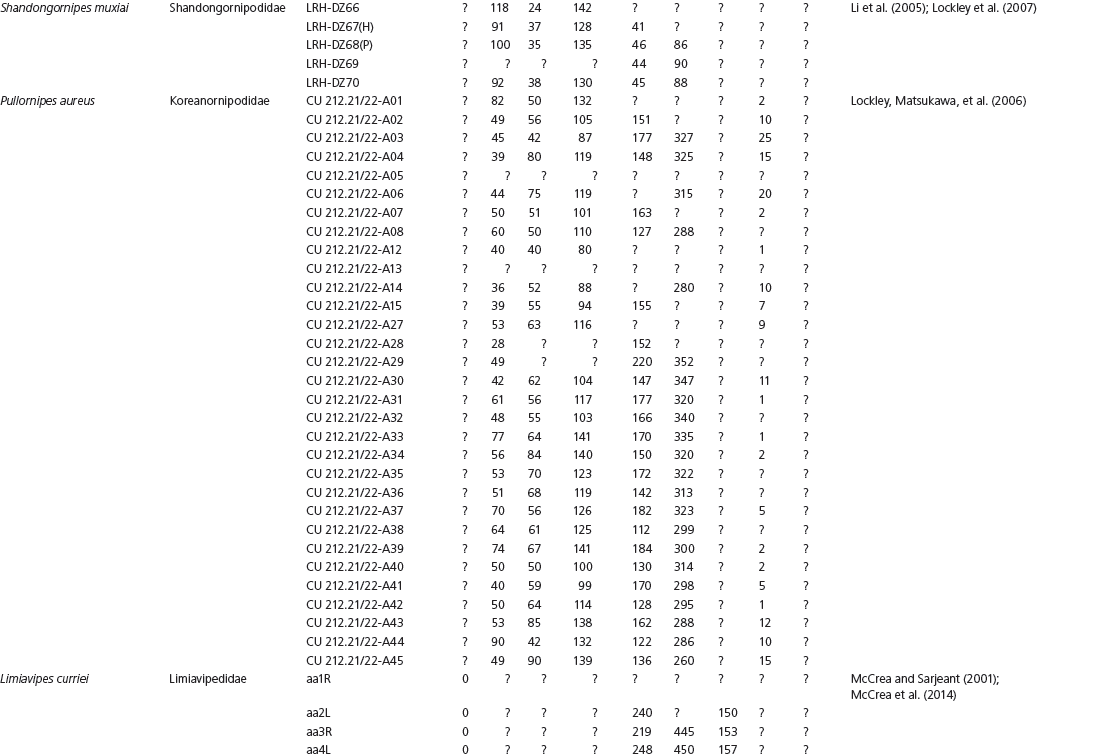

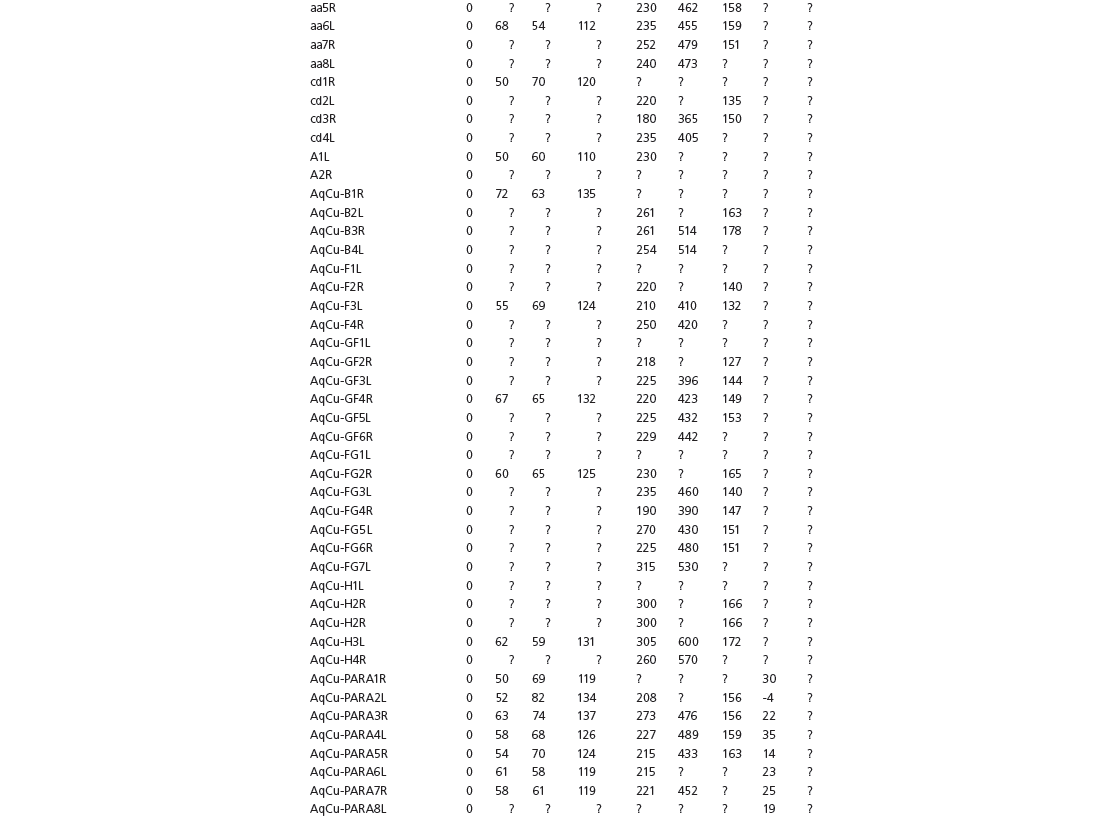

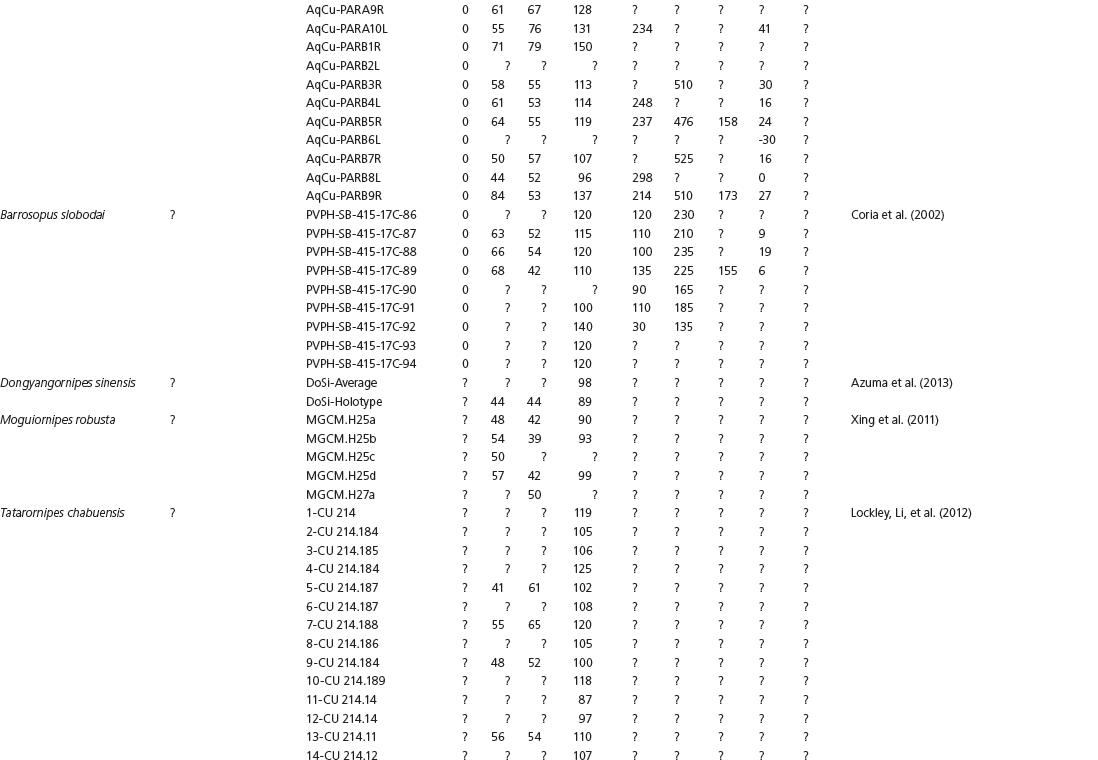

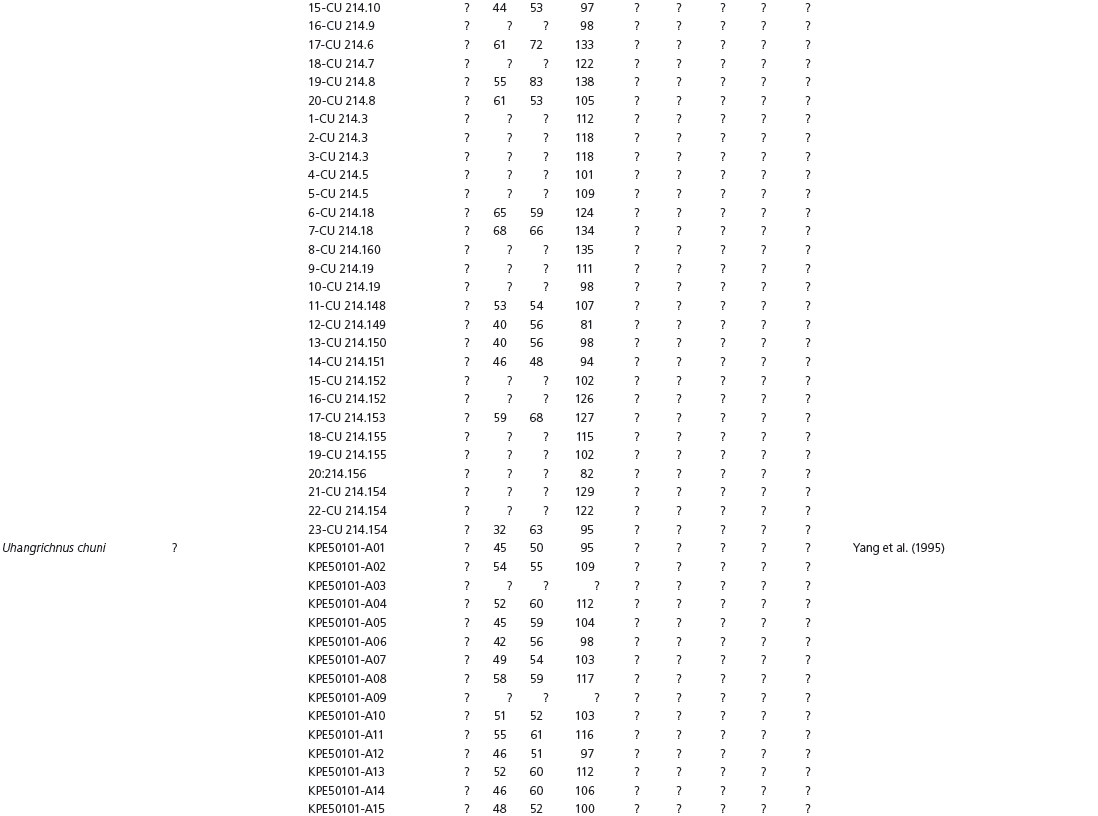

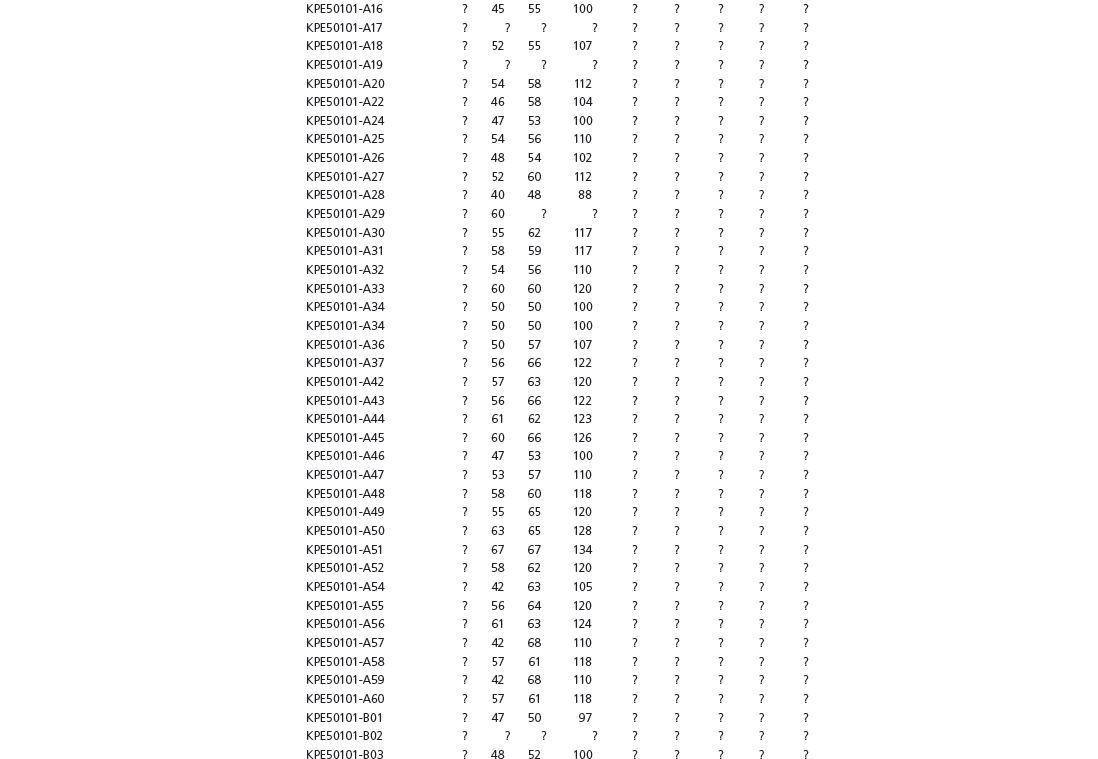

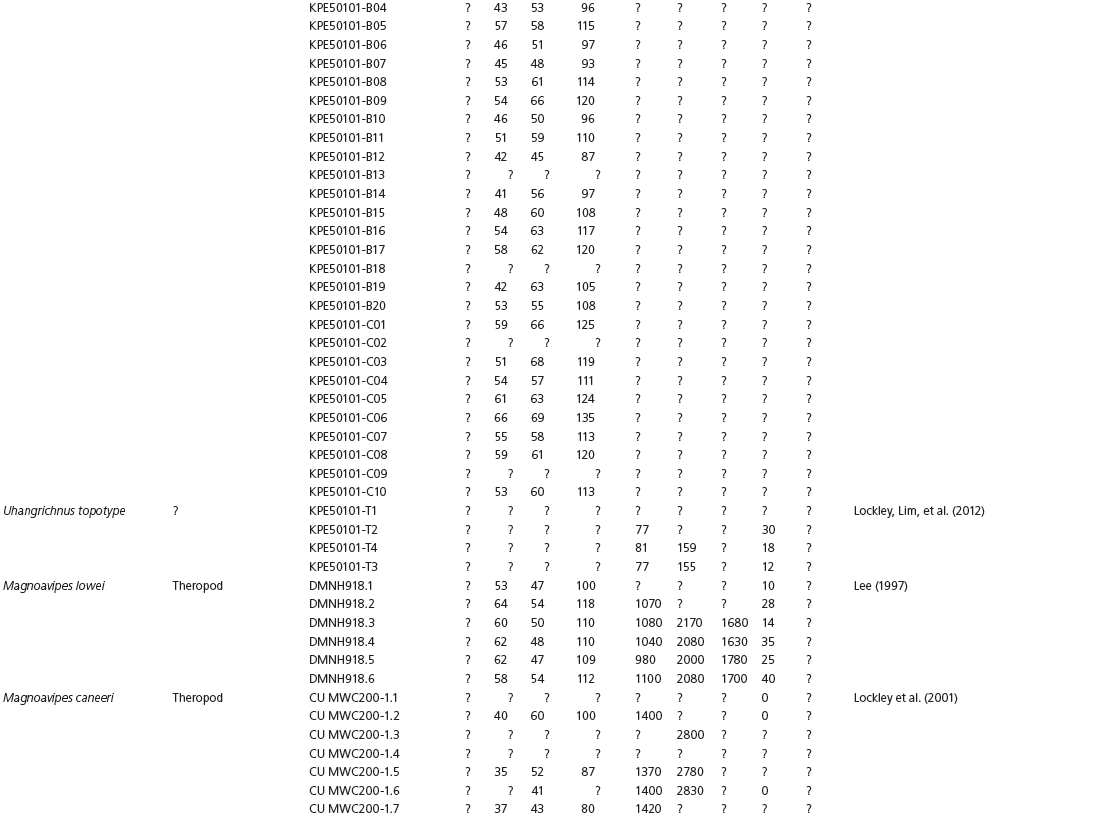

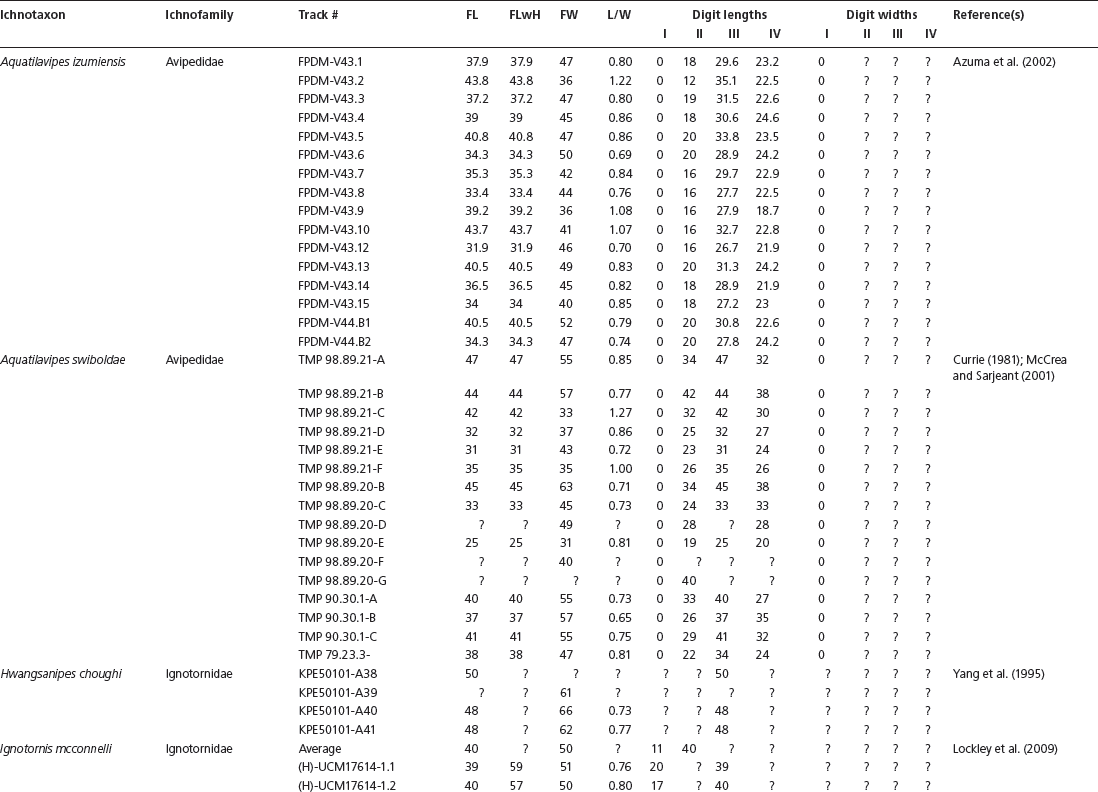

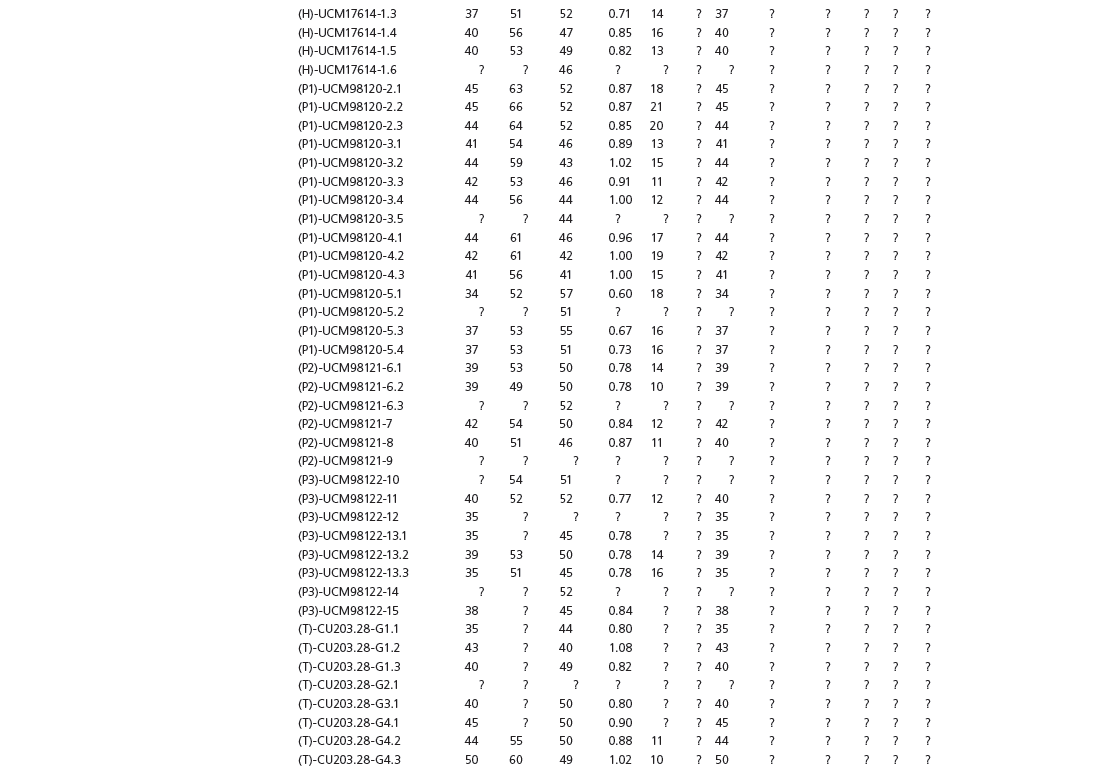

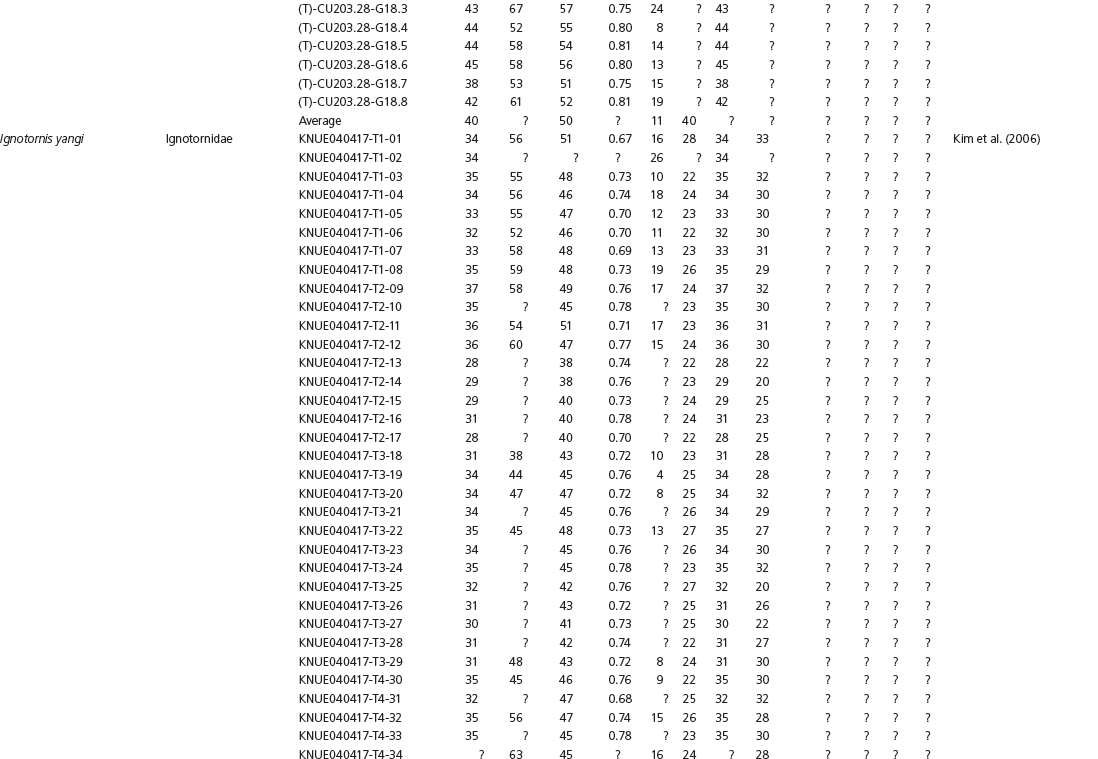

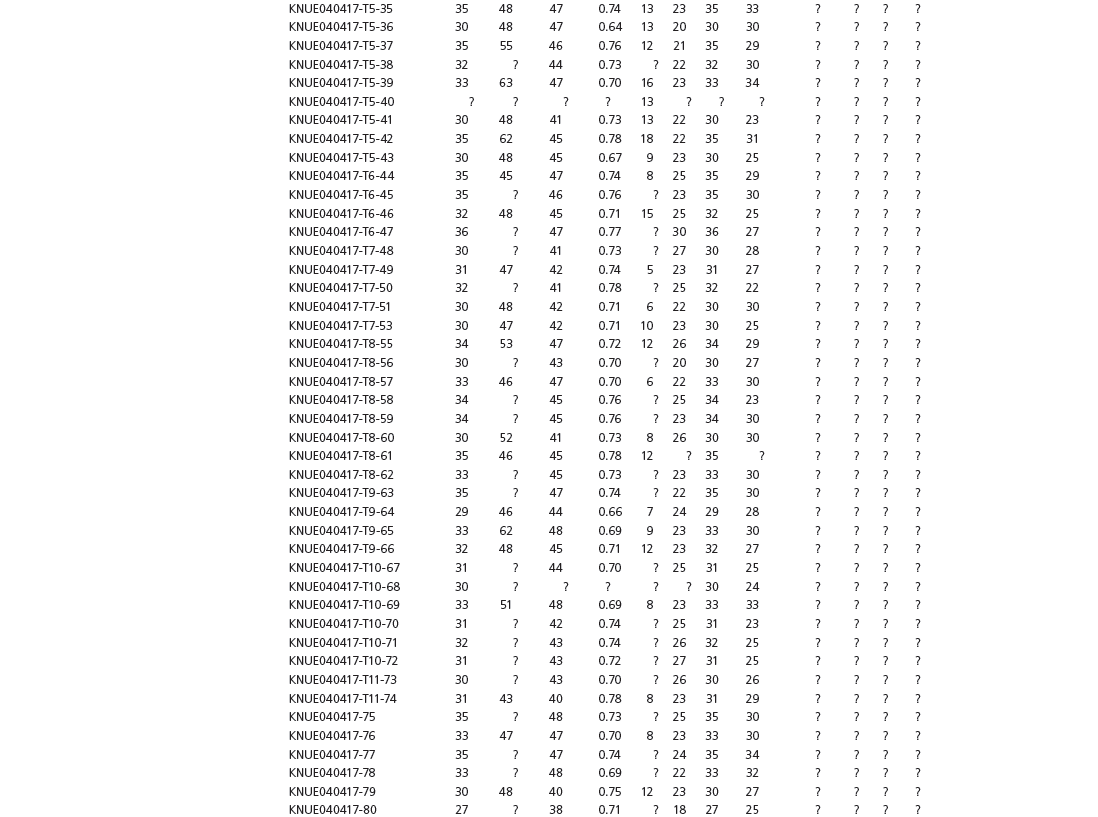

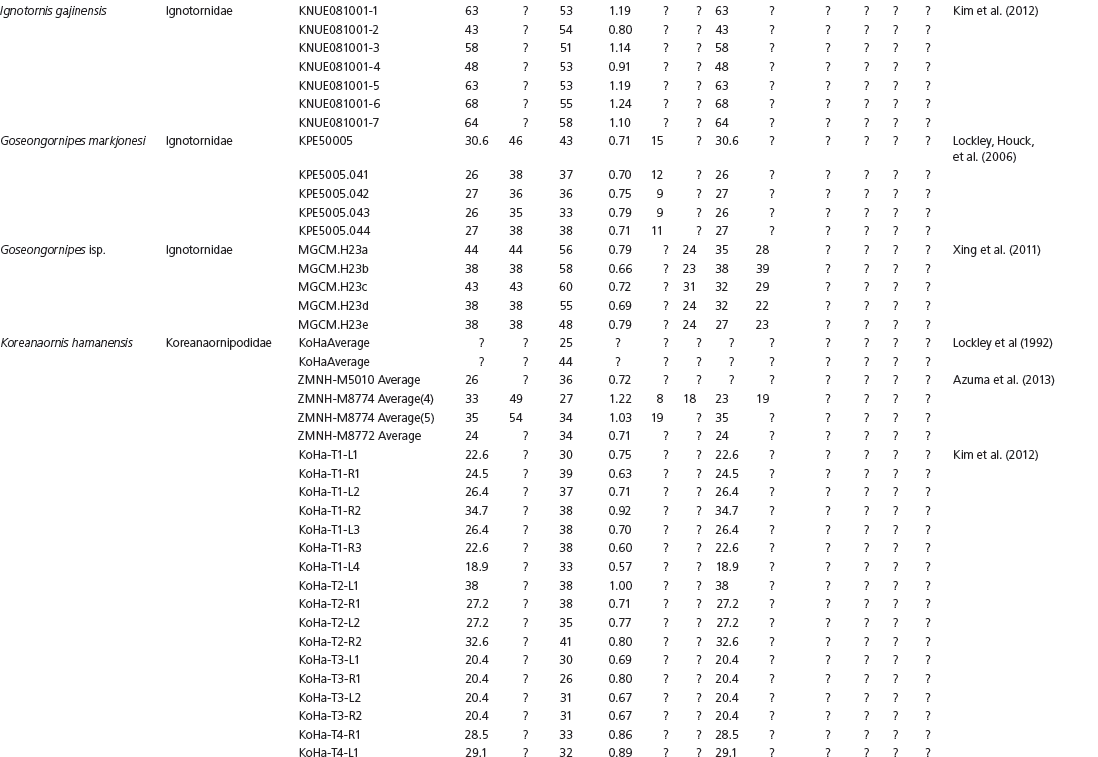

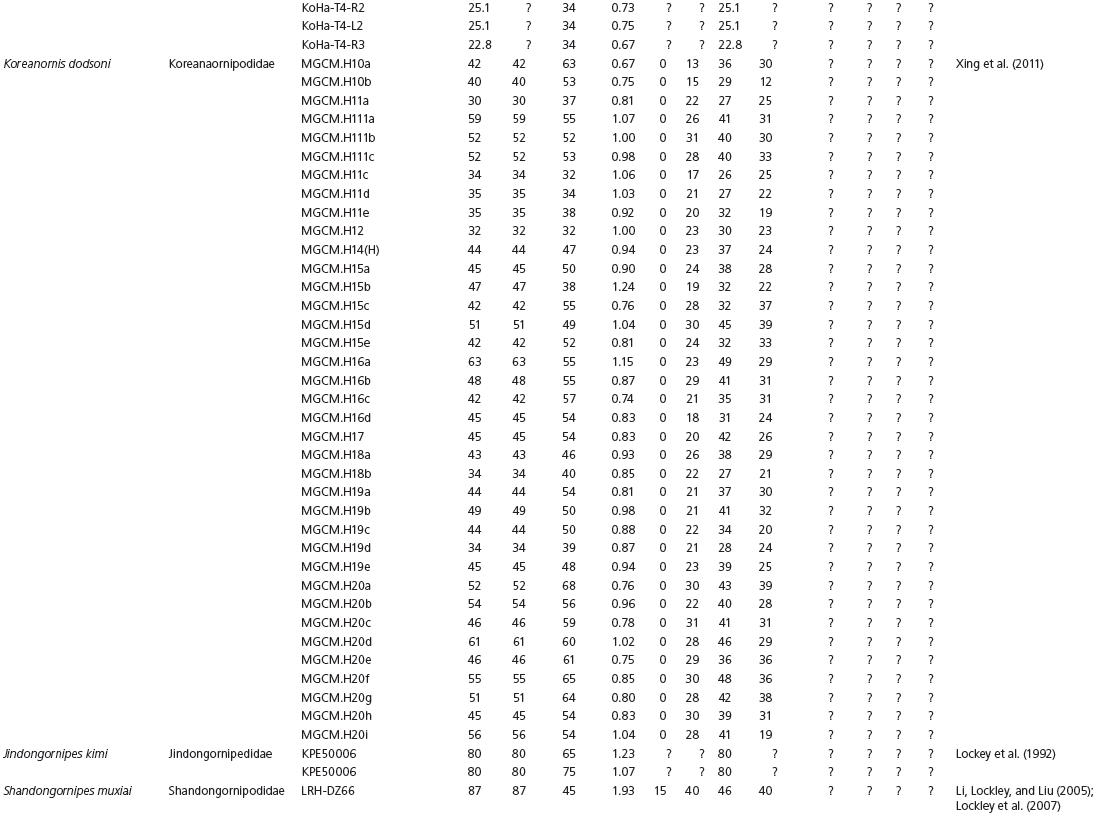

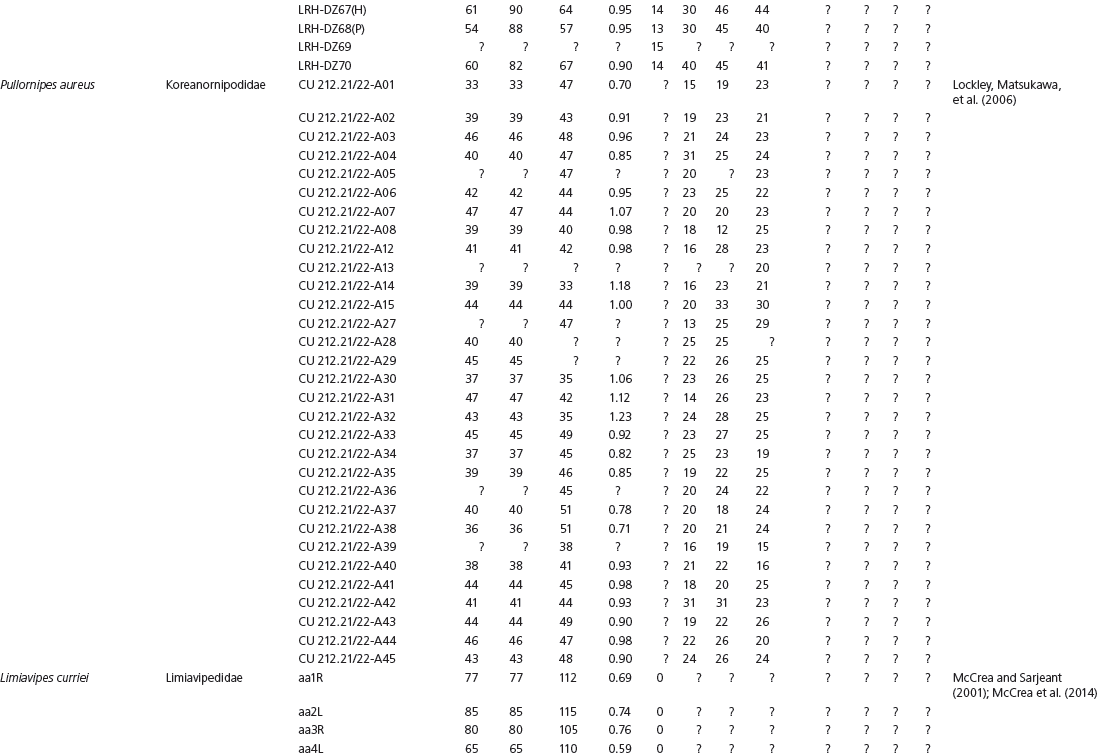

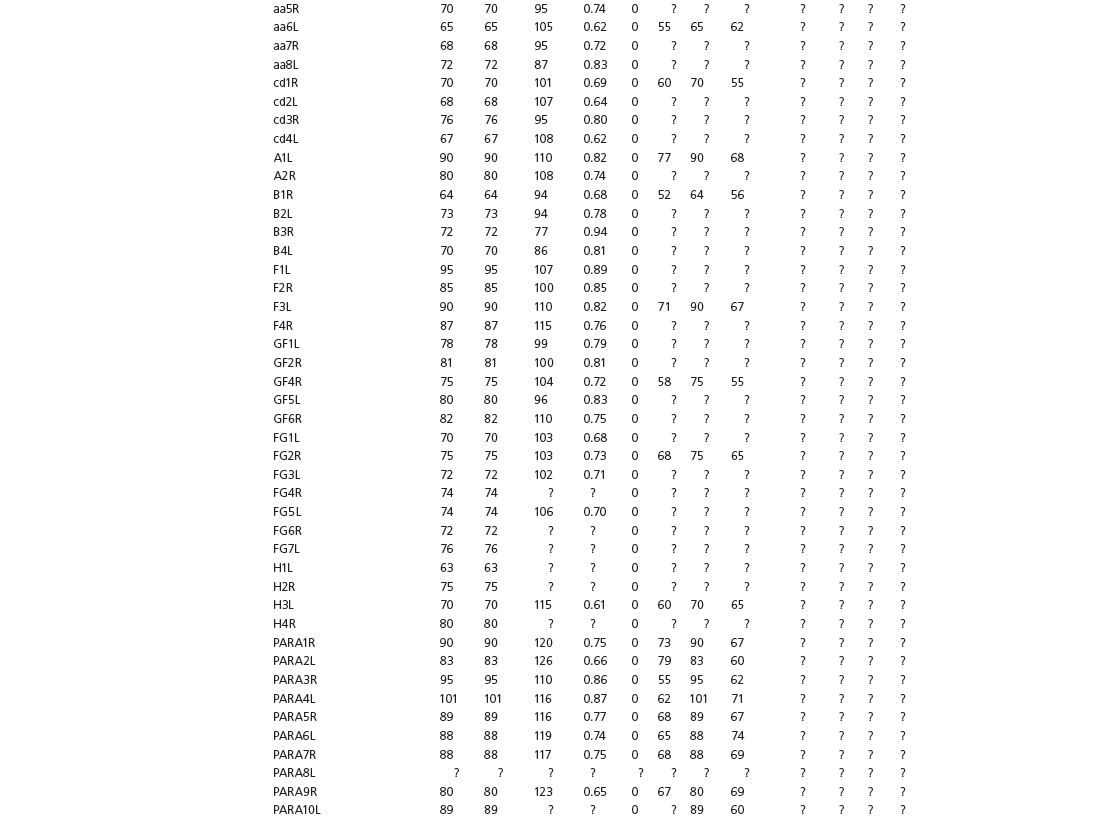

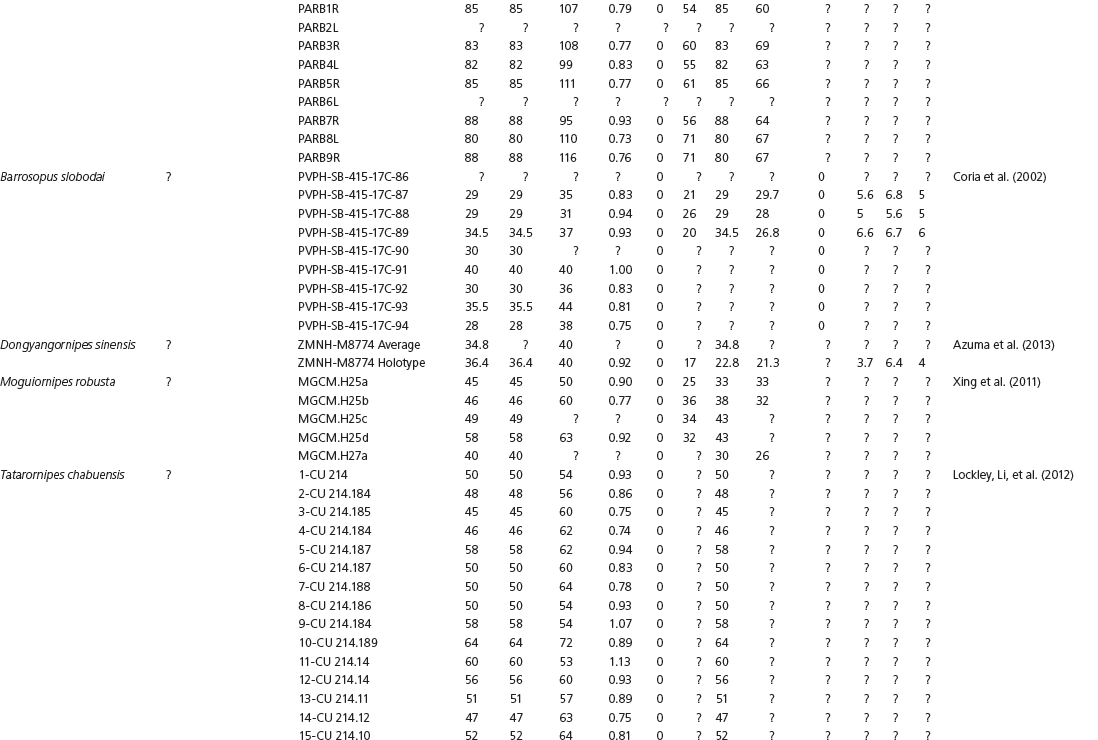

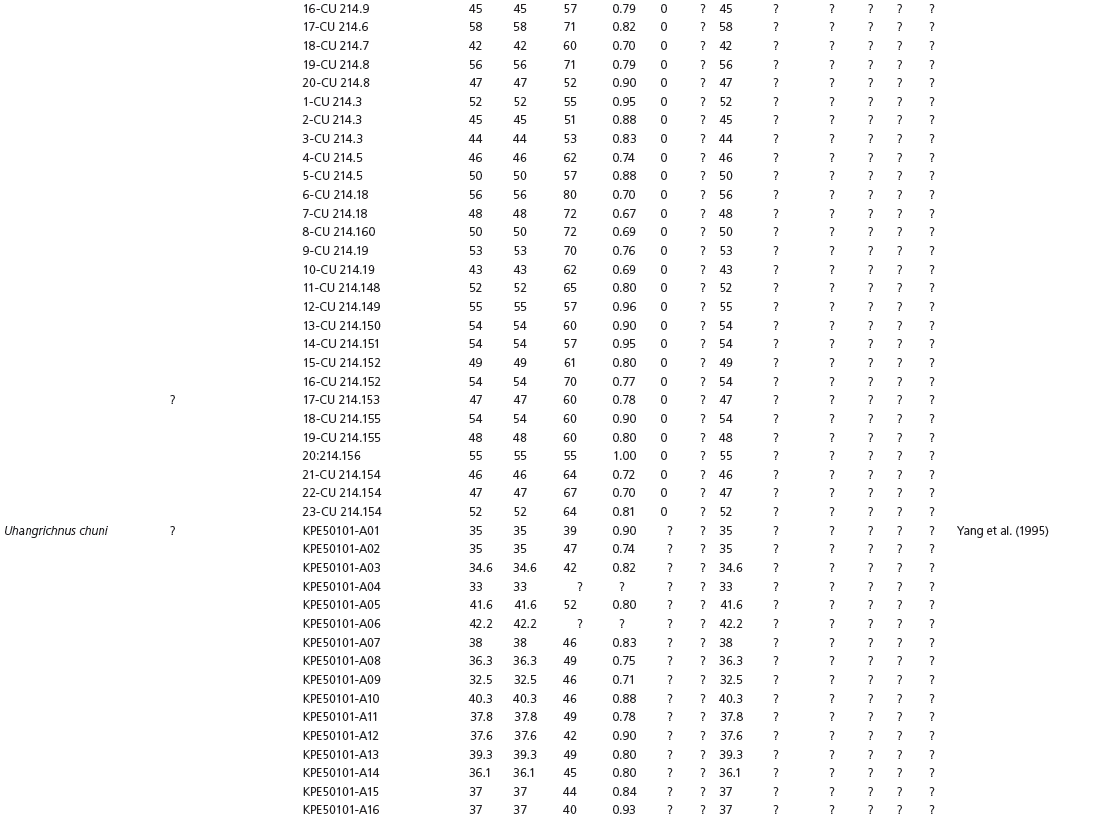

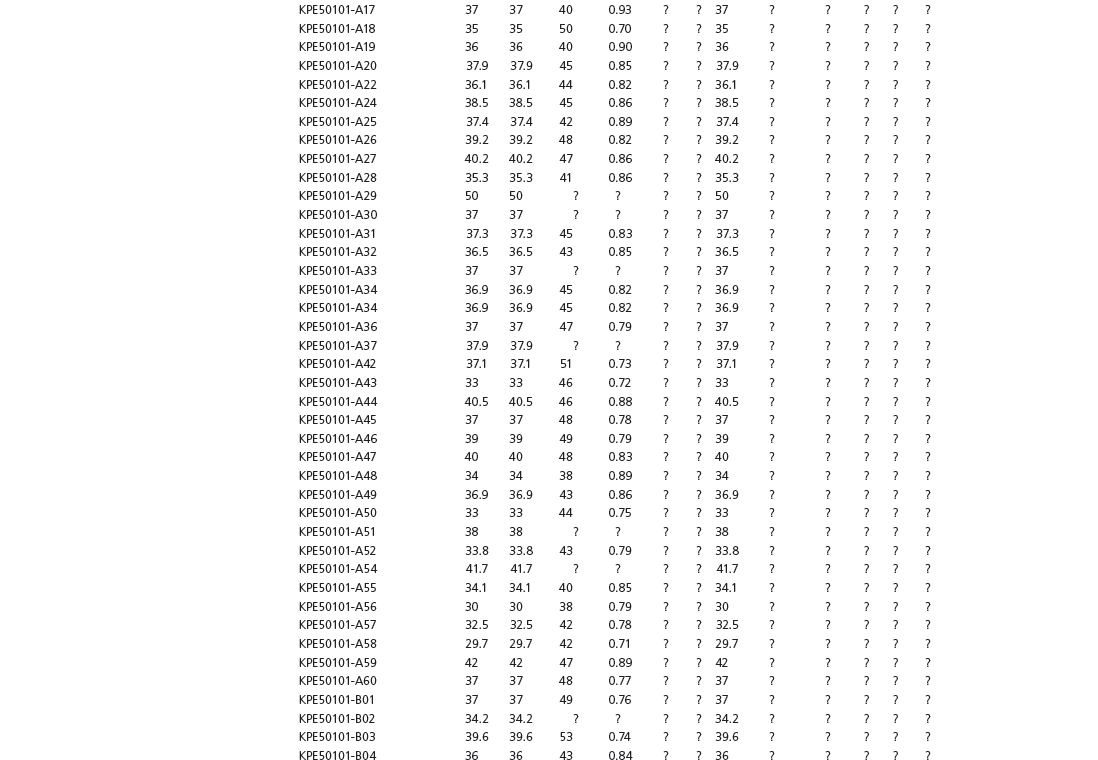

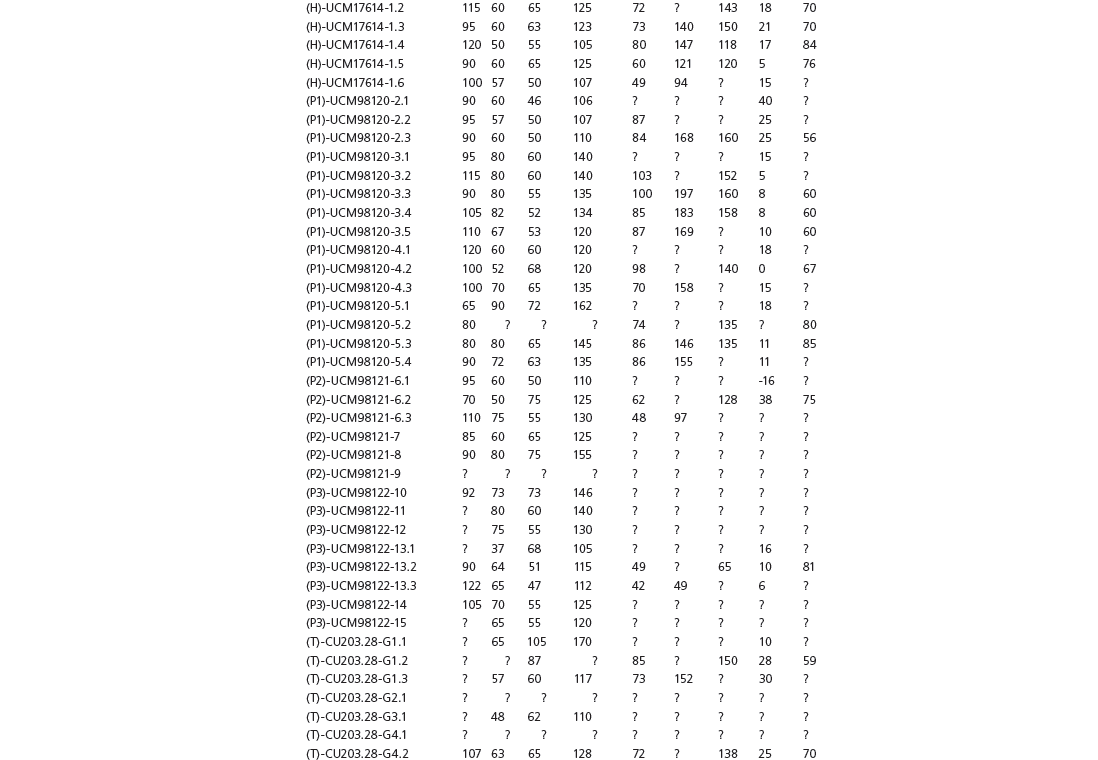

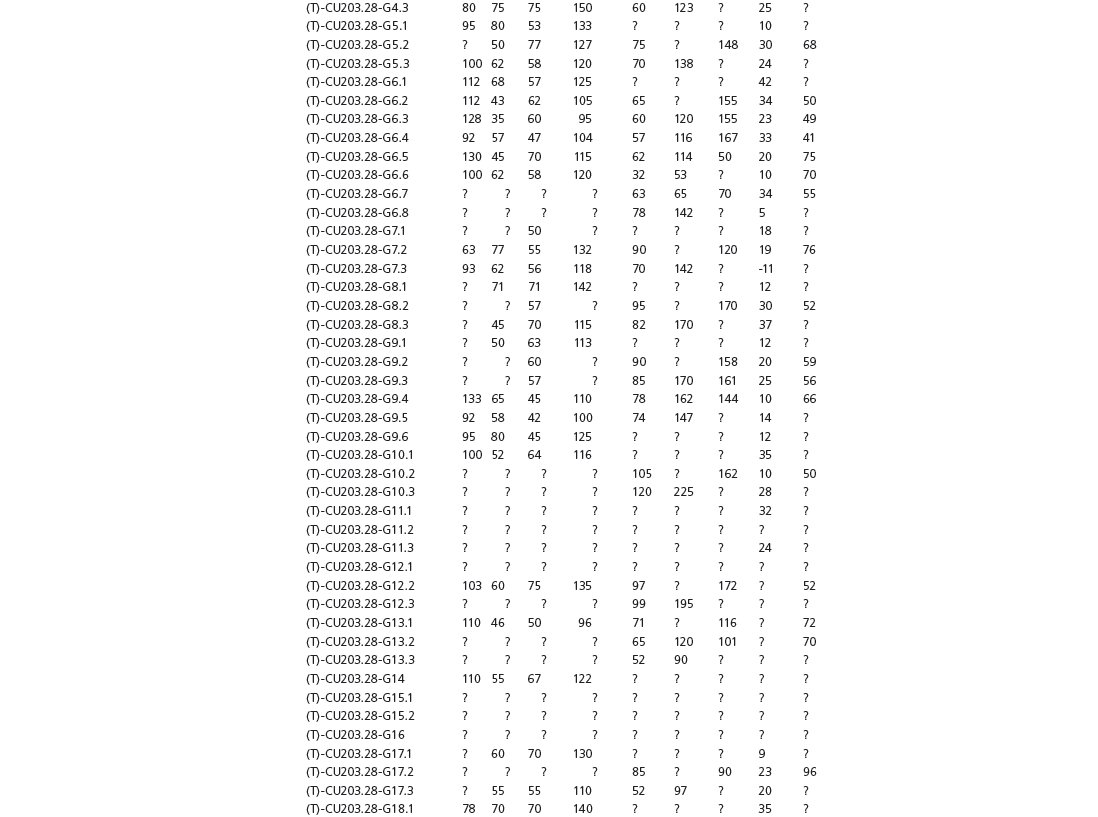

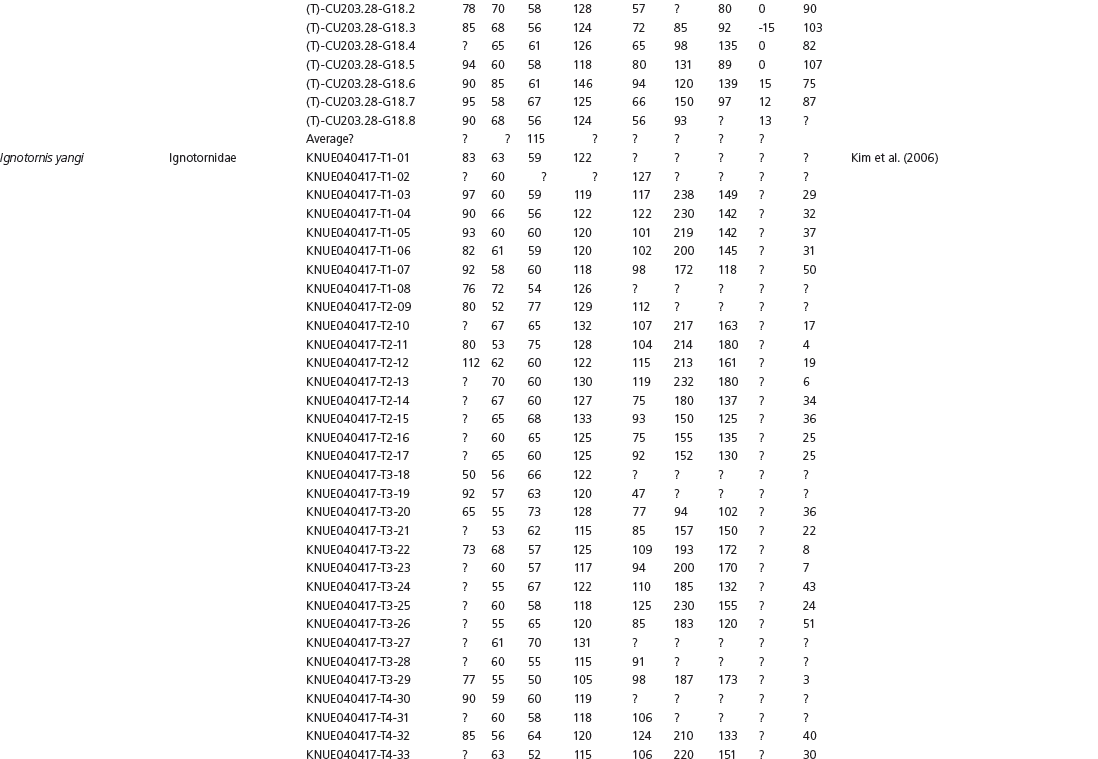

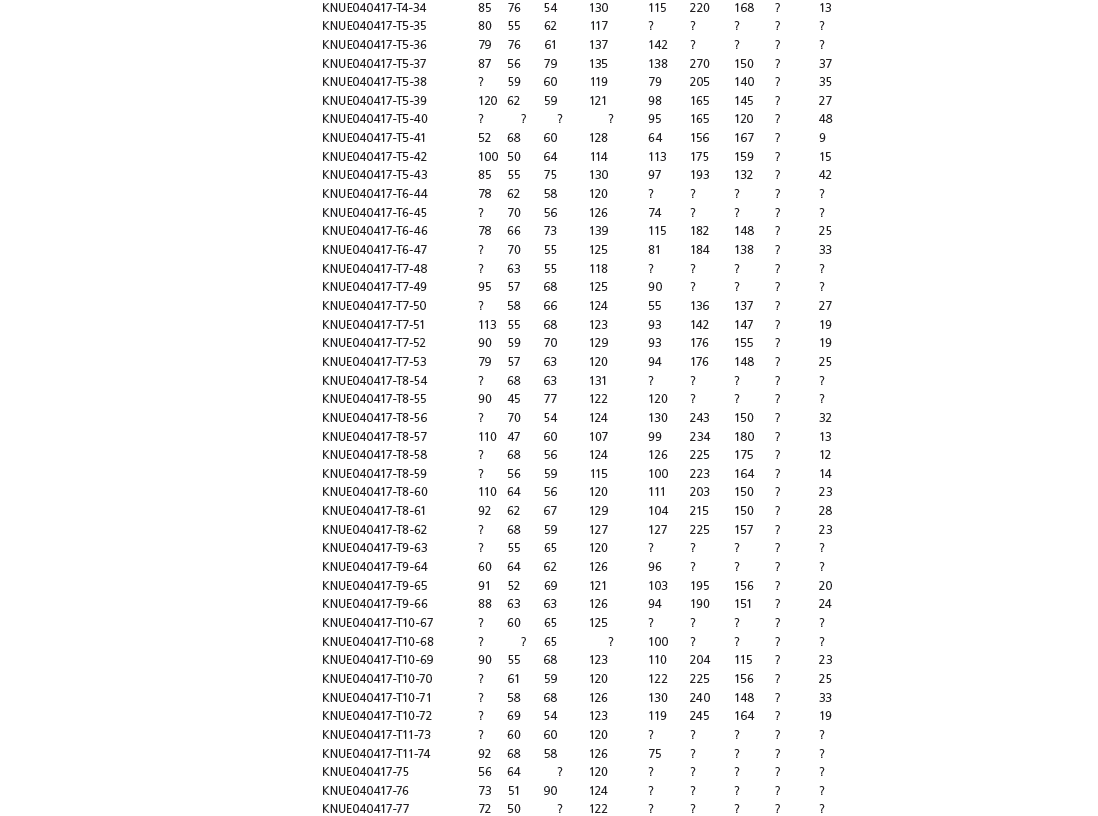

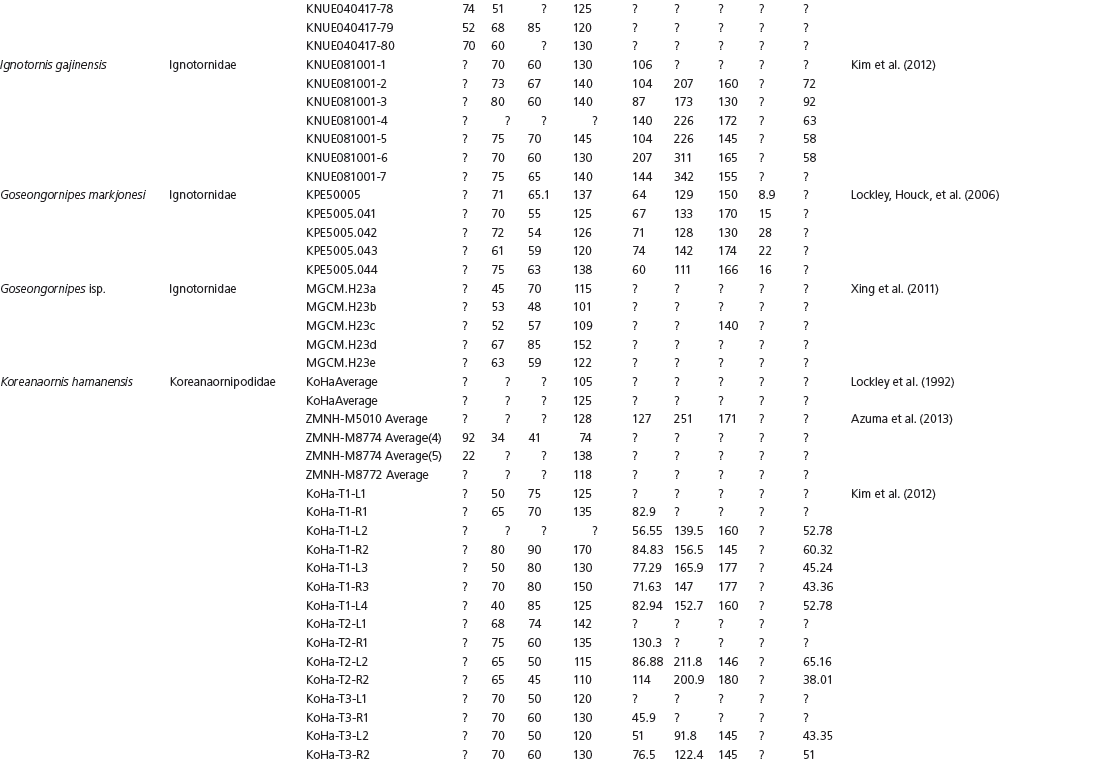

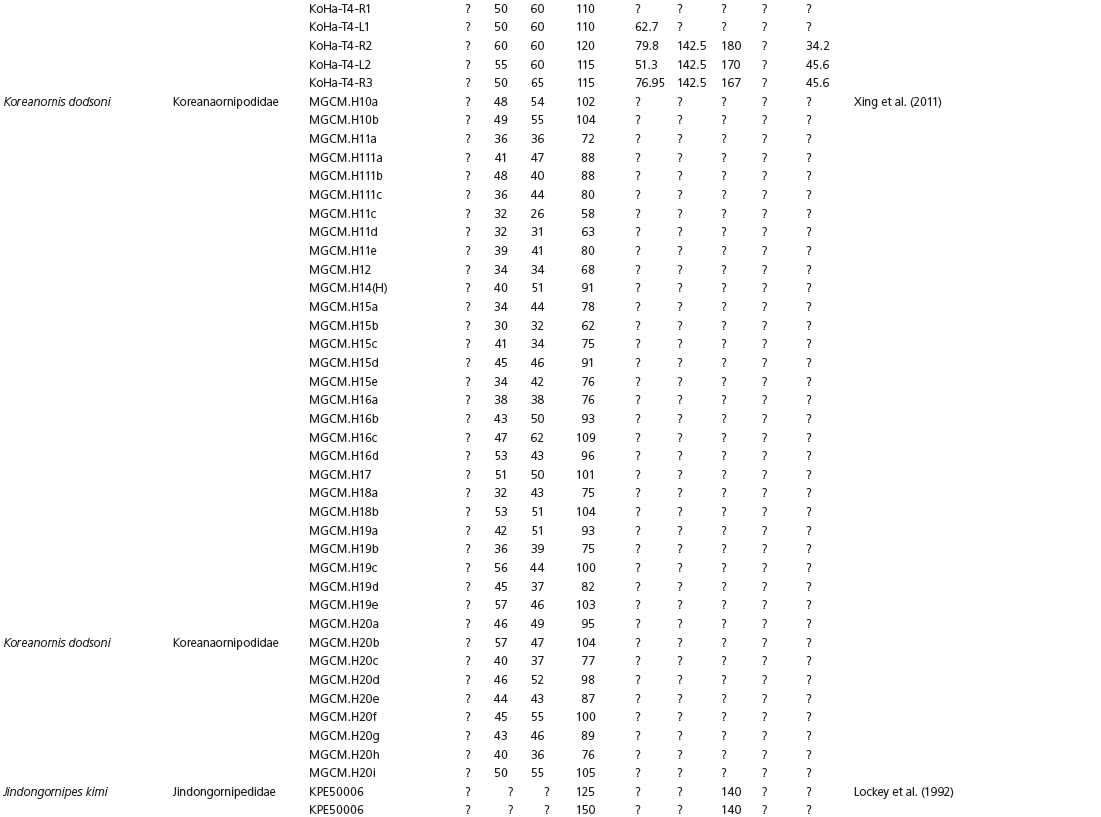

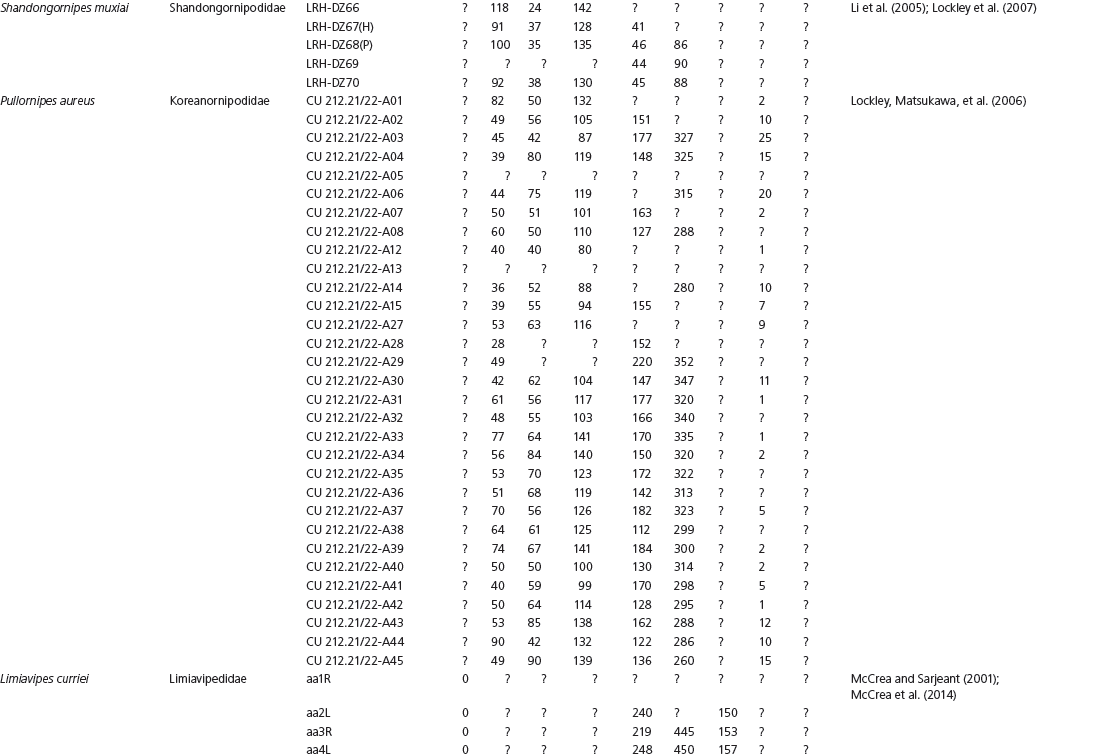

APPENDIX 15.1

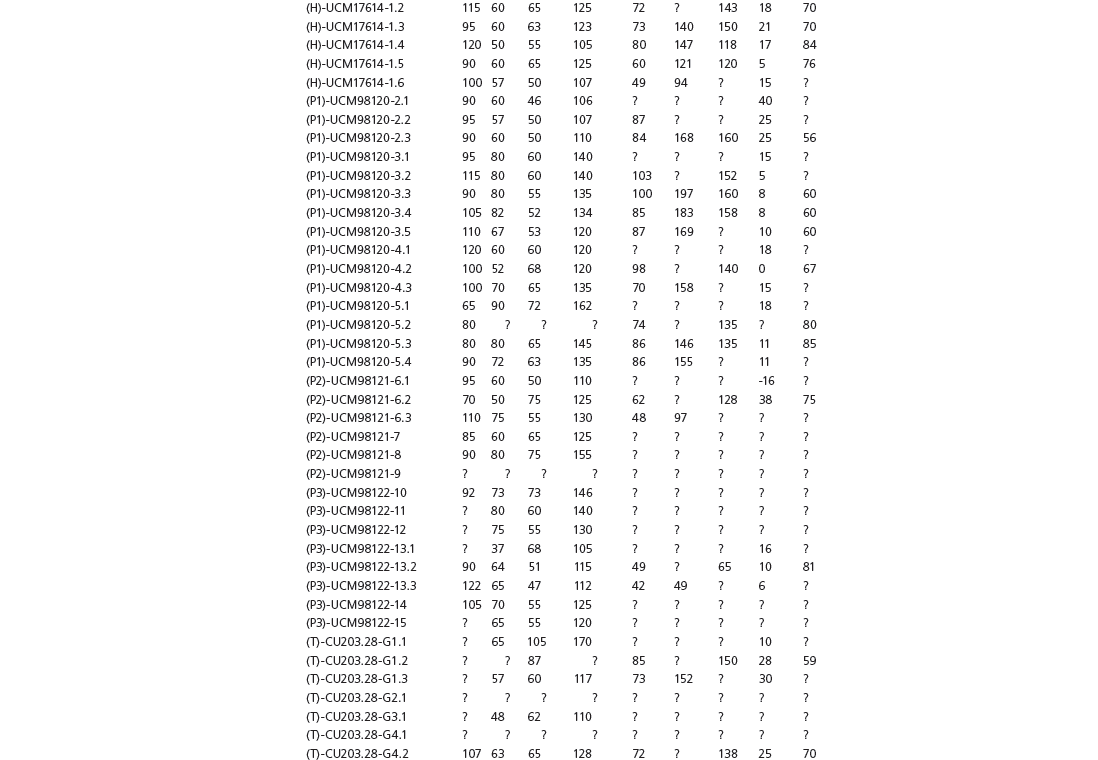

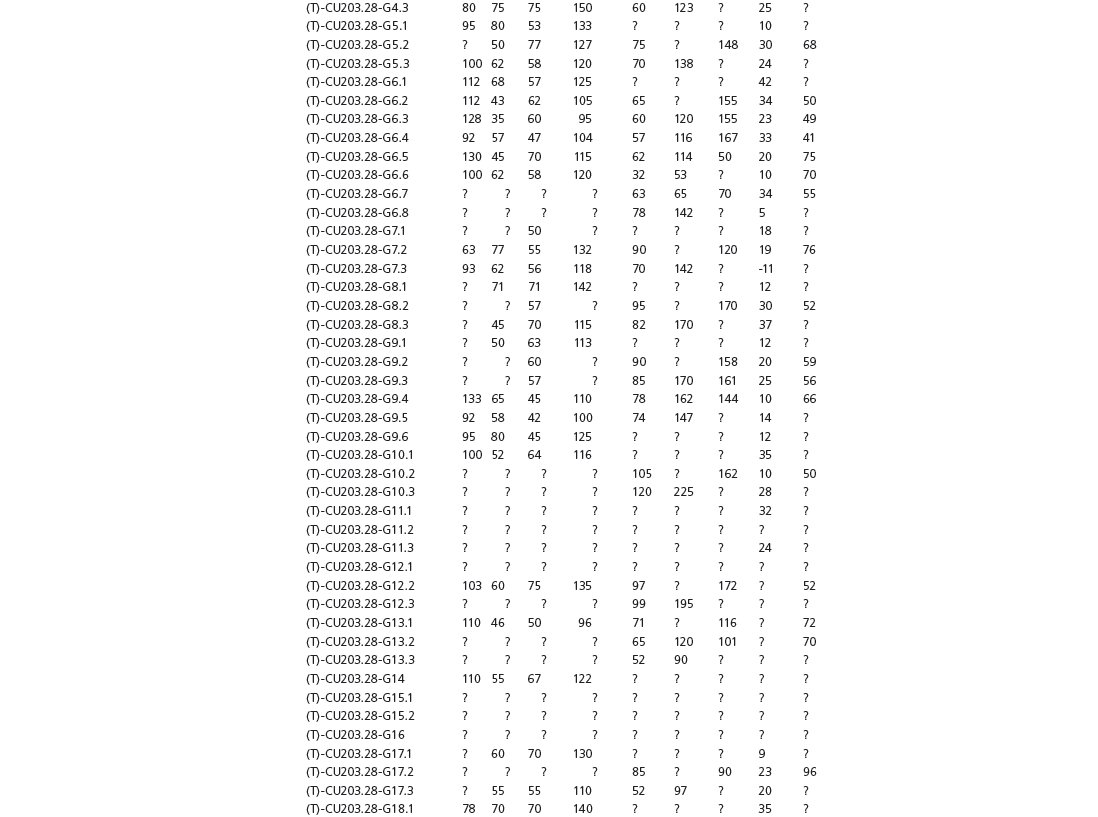

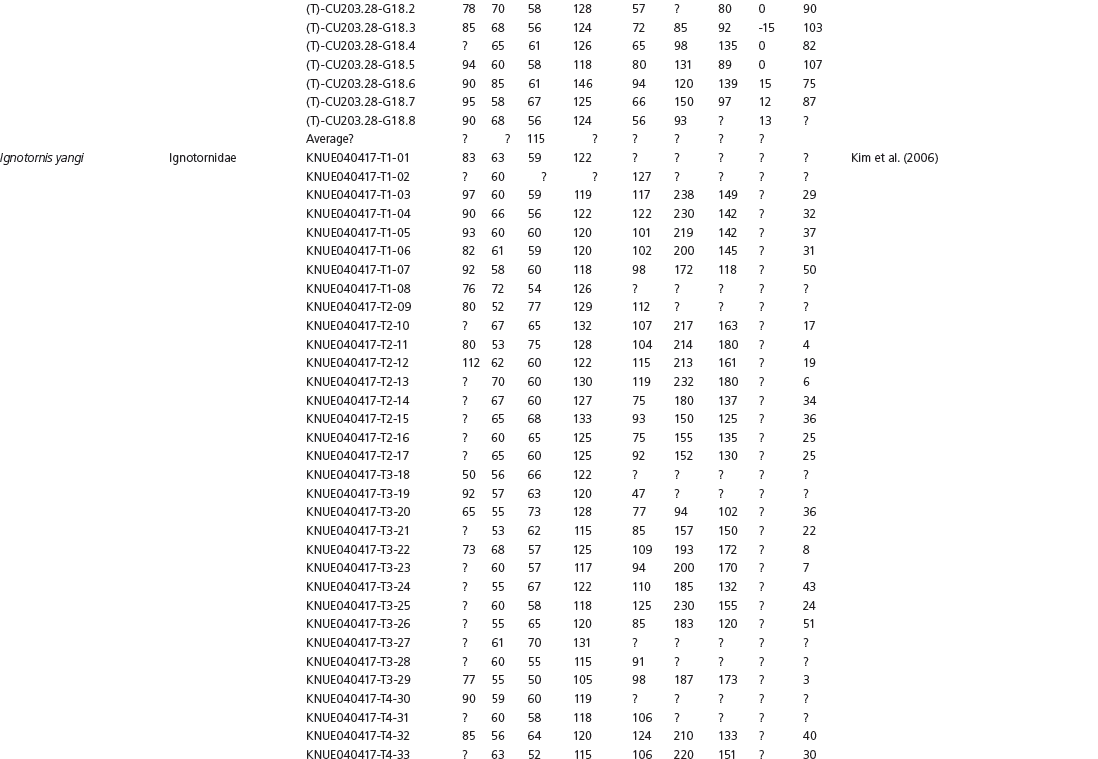

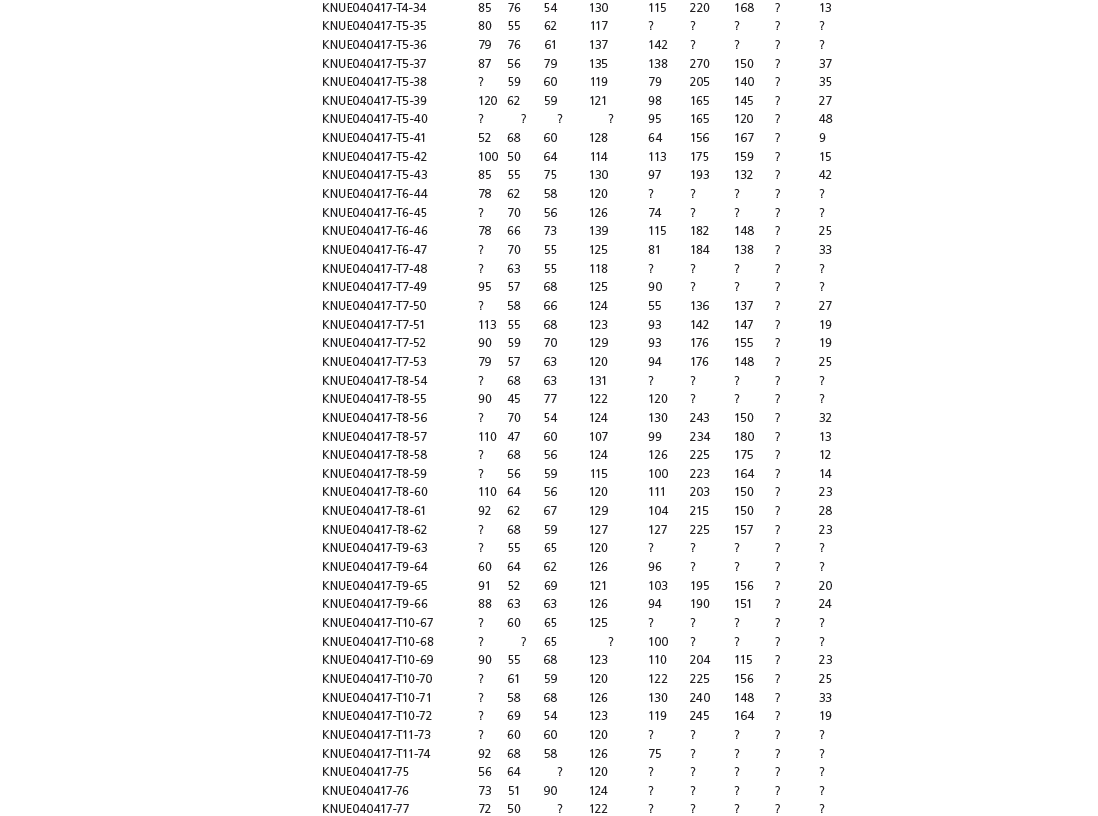

Data used in multivariate analyses of Mesozoic avian ichnotaxa. Data were compiled from references cited within the table. All data were standardized to fit the table presented here. Missing data are indicated by a question mark. Data that are not present due to morphology (i.e., no digit I) are indicated by a zero. All linear measurements are in millimeters. All angle measurements are in degrees. All data are unadjusted.

DATA ABBREVIATIONS

DIV, digit divarication; DIVTOT, digit divarication II–IV; DL, digit length; DW, digit width; FL, footprint length; FLwH, footprint length including hallux; FR, footprint rotation; FW, footprint width; (H), holotype; I, digit I; II, digit II; III, digit III; IV, digit IV; KoHa, Koreanaornis hamanensis; L/W, footprint length to footprint width ratio; (P), paratype; PA, pace angulation; PL, pace length; SL, stride length; (T), topotype; TW, trackway width.

INSTITUTIONAL ABBREVIATIONS

CU, University of Colorado Denver, Dinosaur Tracks Museum; DMNH, Denver Museum of Natural History, Denver, Colorado; FPDM, Fukui Prefectural Dinosaur Museum, Japan; KNUE, Korea National University of Education, Cheongwon, Chungbuk, Korea; KPE, Kyungpook National University, Earth Science Education Department, Taegu, South Korea; LRH, Qingdao Institute of Marine Geology; MGCM, Moguicheng Dinosaur and Bizarre Stone Museum, Xinjiang, China; MWC, Museum of Western Colorado; PVPH, Paleontolga de Vertebrados, Museo del Neuquen, Argentina; TMP, Tyrell Museum of Palaeontology; UCM; University of Colorado Museum of Natural History at Boulder, Colorado; ZMNH, Zhejiang Natural History Museum, Zheijiang, China.

Table 15A.1. Linear measurements

Table 15A.2. Ratios

REFERENCES

Azuma, Y., Y. Arakawa, Y. Tomida, and P. J. Currie. 2002. Early Cretaceous bird tracks from the Tetori Group, Fukui Prefecture, Japan. Memoir of the Fukui Prefectural Dinosaur Museum 1: 1–6.

Azuma, Y., J. Lü, X. Jin, Y. Noda, M. Shibata, R. Chen, and W. Zheng. 2013. A bird footprint assemblage of early Late Cretaceous age, Dongyang City, Zhejiang Province, China. Cretaceous Research 40: 3–9.

Bunni, M. K. 1959. The Killdeer (Charadrius vociferus), Linnaeus, in the breeding season: ecology, behavior, and the development of homoiothermism. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan, 348 pp.

Buckley, L. G., R. T. McCrea, and M. G. Lockley. 2015. Birding by foot: a critical look at the synapomorphy- and phenetic-based approaches to trackmaker identification of enigmatic tridactyl Mesozoic traces. Ichnos 22(3–4): 192–207.

Carrier, D., and L. R. Leon. 1990. Skeletal growth and function in the California gull (Larus californicus). Journal of Zoology 222: 375–389.

Chun, S. S. 1990. Sedimentary processes depositional environments and tectonic setting of the Cretaceous Uhangri Formation. Ph.D. dissertation, Seoul National University, Department of Oceanography, Seoul, Korea, 328 pp.

Coria, R. A., P. J. Currie, D. Eberth, and A. Garrido. 2002. Bird footprints from the Anacleto Formation (Late Cretaceous) in Neuquén Province, Argentina. Ameghiniana 39: 1–11.

Currie, P. J. 1981. Bird footprints from the Gething Formation (Aptian, Lower Cretaceous) of northeastern British Columbia, Canada. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 1(3–4): 257–264.

Dial, K. P. 2003. Evolution of avian locomotion: correlates of flight style, locomotor modules, nesting biology, body size, development, and the origin of flapping flight. Auk 120(4): 941–952.

Falk, A. R., L. D. Martin, and S. T. Hasiotis. 2011. A morphologic criterion to distinguish bird tracks. Journal of Ornithology 152: 701–716.

Farlow, J. O., S. M. Gatesy, T. R. Holtz, J. R. Hutchinson, and J. M. Robinson. 2000. Theropod locomotion. American Zoologist 40: 640–663.

Fiorillo, A. R., S. T. Hasiotis, Y. Kobayashi, B. H. Breithaupt, and P. J. McCarthy. 2011. Bird tracks from the Upper Cretaceous Cantwell Formation of Denali National Park, Alaska, USA: a new perspective on ancient northern polar diversity. Journal of Systematic Palaeontology 9(1): 33–49.

Gatesy, S. M. 1990. Caudofemoral musculature and the evolution of theropod locomotion. Paleobiology, 170–186.

Gill, F. B. 2007. Ornithology. 3rd edition. New York: W. H. Freeman and Company, 758 pp.

Hammer, Ø., and D. A. T. Harper. 2006. Paleontological data analysis. Wiley-Blackwell, Malden, Massachusetts, 351 pp.

Hammer, Ø., D. A. T. Harper, and P. D. Ryan. 2001. PAST: paleontological statistics software package for education and data analysis. Palaeontologia Electronica 4: 9 pp.

Huh, M., M. G. Lockley, K. S. Kim, J. Y. Kim, and S. G. Gwak. 2012. First report of Aquatilavipes from Korea: new finds from Cretaceous strata in the Yeosu Islands Archipelago. Ichnos 19(1–2): 43–49.

Jackson, B. J., and J. A. Jackson. 2000. Killdeer (Charadrius vociferus); in A. Poole (ed.), The Birds of North America Online. Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, New York. Available at http://bna.birds.cornell.edu.login.ezproxy.library.ualberta.ca/bna/species/517, doi:10.2173/bna.517. Accessed November 9, 2015.

Kim, B. K. 1969. A study of several sole marks in the Haman Formation. Journal of the Geological Society of Korea 5(4): 243–258.

Kim, J. Y., S. H. Kim, K. S. Kim, and M. G. Lockley. 2006. The oldest record of webbed bird and pterosaur tracks from South Korea (Cretaceous Haman Formation, Changseon and Sinsu Islands): more evidence of high avian diversity in East Asia. Cretaceous Research 27(1): 56–69.

Kim, J. Y., M. G. Lockley, S. J. Seo, K. S. Kim, S. H. Kim, and K. S. Baek. 2012. A paradise of Mesozoic birds: the world’s richest and most diverse Cretaceous bird track assemblage from the Early Cretaceous Haman Formation of the Gajin tracksite, Jinju, Korea. Ichnos 19(1–2): 28–42.

Lee, Y. -N. 1997. Bird and dinosaur footprints in the Woodbine Formation (Cenomanian), Texas. Cretaceous Research 18(6): 849–864.

Li, R., M. G. Lockley, & M. Liu. 2005. A new ichnotaxon of fossil bird track from the Early Cretaceous Tianjialou Formation (Barremian-Albian), Shandong Province, China. Chinese Science Bulletin 50(11): 1149–1154.

Lockley, M. G. 2007. A 25-year anniversary celebration of the discovery of fossil footprints of South Korea. Haenam-gun, Jeollanam-do, southwestern Korea; pp. 41–62 in Proceedings of the Haenam Uhangri International Dinosaur Symposium, February 22–23.

Lockley, M. G., and E. Rainforth. 2002. The tracks record of Mesozoic birds and pterosaurs: an ichnological and paleoecological perspective; pp. 405–418 in L. Chiappe and L. M. Witmer (eds.), Mesozoic Birds above the Heads of Dinosaurs. University of California Press, Berkeley, California.

Lockley, M. G., and J. D. Harris. 2010. On the trail of early birds: a review of the fossil footprint record of avian morphological and behavioural evolution; pp. 1–63 in P. K. Ulrich and J. H. Willett (eds.), Trends in Ornithology Research. Nova Science Publishers, Hauppauge, New York.

Lockley, M. G., and M. Matsukawa. 2009. A review of vertebrate track distributions in East and Southeast Asia. Journal Paleontological Society of Korea 25(1): 17–42.

Lockley, M. G., G. Nadon, and P. J. Currie. 2004. A diverse dinosaur-bird footprint assemblage from the Lance Formation, Upper Cretaceous, eastern Wyoming: implications for ichnotaxonomy. Ichnos 11(3–4): 229–249.

Lockley, M. G., J. L. Wright, and M. Matsukawa. 2001. A new look at Magnoavipes and so-called big bird tracks from Dinosaur Ridge (Cretaceous, Colorado). Mountain Geologist 38(3): 137–146.

Lockley, M. G., J. Li, M. Matsukawa, and R. Li. 2012. A new avian ichnotaxon from the Cretaceous of Nei Mongol, China. Cretaceous Research 34: 84–93.

Lockley, M., K. Chin, K. Houck, M. Matsukawa, and R. Kukihara. 2009. New interpretations of Ignotornis, the first-reported Mesozoic avian footprints: implications for the paleoecology and behavior of an enigmatic Cretaceous bird. Cretaceous Research 30(4): 1041–1061.

Lockley, M. G., K. Houck, S. Y. Yang, M. Matsukawa, and S. K. Lim. 2006. Dinosaur-dominated footprint assemblages from the Cretaceous Jindong Formation, Hallyo Haesang national park area, Goseong County, South Korea: evidence and implications. Cretaceous Research 27(1): 70–101.

Lockley, M. G., R. Li, J. D. Harris, M. Matsukawa, and M. Liu. 2007. Earliest zygodactyl bird feet: evidence from Early Cretaceous roadrunner-like tracks. Naturwissenschaften 94(8): 657–665.

Lockley, M. G., S. Y. Yang, M. Matsukawa, F. Fleming, and S. K. Lim. 1992. The track record of Mesozoic birds: evidence and implications. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 336(1277): 113–134.

Lockley, M. G., J. D. Lim, J. Y. Kim, K. S. Kim, M. Huh, and K. G. Hwang. 2012. Tracking Korea’s early birds: a review of Cretaceous avian ichnology and its implications for evolution and behavior. Ichnos 19(1–2): 17–27.

Lockley, M. G., M. Matsukawa, H. Ohira, J. Li, J. Wright, D. White, and P. Chen. 2006. Bird tracks from Liaoning Province, China: new insights into avian evolution during the Jurassic-Cretaceous transition. Cretaceous Research 27(1): 33–43.