12 Me, myself and I

Life goes on here without fading or flowering, or rather death never ends. The many kinds of objects differ only in their rhythm of attrition or renewal, not in their fate. A pencil lasts a week; then it has run its course and is replaced by an identical one … The rush-seat chair is allotted three years until it is due to be replaced, the individual who sits out his life on it some thirty or thirty-five years of service; then a new individual is seated on the chair, just the same as the old one.

— Stefan Zweig1

Do you ring a doorbell with a finger or a thumb? The answer will reveal your age almost as accurately as the way you dance or how wrinkly your hands are. The older you are, the likelier you will be to press it with a finger, probably your index finger. If you are younger, you may well use a thumb, because it will have been exercised so thoroughly by typing text messages and gunning down digital assailants on game consoles that it is likely to be stronger and nimbler than any of your fingers.

Ringing a doorbell is one of those mundane actions to which we give little thought, but execute instinctively, as efficiently as possible. Making the unconscious choice to use a thumb, rather than a finger, demonstrates how changes in our designed environment can affect our behaviour. Another example is how many once-useful skills, often painfully acquired, have become, if not quite obsolete, no longer as valuable as they once were. Who needs a good sense of direction in the age of Google Maps and satellite navigation systems? An ability to spell now we have spellcheck programs? A talent for mental arithmetic when phones have calculator apps? And as for being good at inventing games, useful though that once was, these days there is World of Warcraft or Angry Birds.

Conversely, we have acquired new skills; so many that one of them is an aptitude for change. The contents of our daily lives have changed more dramatically since the Internet’s invention in 1991 than at any time since the introduction of electricity at the turn of the twentieth century.2 Think of the dozens of new technologies we have to learn to use every year. Controlling a computer by moving your hands once seemed thrillingly futuristic, but is now a standard component of video games. The same goes for passing through airport security without showing your passport because you can verify your identity by popping into a booth to scan your irises,3 and for checking on to a flight using your smartphone rather than a printed boarding pass. So many technologies come and go that no sooner have we trained ourselves to use a new form of hardware or software than another appears and the learning process starts again.

We have become equally adept at multitasking. There was a time when being ‘on the phone’ served as both an excuse and an explanation as to why you could not be expected to do anything else. Now, it is a means of giving a running commentary on whatever else you are doing at the time on a plethora of screens and networks. Using several devices at once has enabled us to do various things simultaneously in other areas of our lives too. Not that it necessarily helps us to concentrate on each one, at least not as intensely as we might wish. When the novelist Zadie Smith cited her ten rules for writing, number seven was to ‘work on a computer that is disconnected from the Internet’.4

Another new skill is synthesizing. Thanks to Moore’s law, we are assailed with so much information that we have had to learn how to ignore the flotsam and spot the gems. We then assess its quality in terms of accuracy and objectivity. Some of the sources will be familiar and trustworthy, like a news app you read every day. Others will be unknown, such as bloggers you have not heard of and may never encounter again, or sources we know to be risky, like Wikipedia. The degree to which the information has been synthesized will vary too. It may have been meticulously researched, fact-checked and edited in the traditional way. Or you may have unearthed raw opinion that could turn out to be anything from scrupulously objective to the type of ragingly opinionated Twitter blasts that the American computer scientist Jaron Lanier described in his book You Are Not a Gadget as reducing personal tragedy and humanitarian disasters to a maximum of one hundred and forty characters.5 How can you tell which is which? With difficulty, but we have all had to try, which is how we have learnt, however laboriously, to become sharper at synthesizing the information that is presented to us online and off. Our visual processing skills have improved for the same reasons, making us more proficient at analysing rapid streams of visual information and at identifying individual images, even ones we see briefly.6

As well as prompting us to learn new skills and to jettison old ones, our experience of the designed environment has changed our expectations. One is that we expect the pace of life to be faster. We are also more amenable to collaboration thanks to all the online petitions we have signed, and useful insights unearthed from collective endeavours like Wikipedia. And we are more questioning, which is not surprising given that all our synthesizing has taught us to be constructively sceptical, as has the knowledge that every image we see, still or moving, may have been digitally altered. Once, when people saw something astonishing, they would say: ‘I can’t believe my eyes.’ Now, we do not expect to be able to. How could we, when we know that the movie star on a magazine cover may not be as slim as she appears, or that pimply teen stars can be ‘cured’ of acne by a few clicks of a mouse?

Significant though all these changes are, another shift in our expectations has even more radical implications for design: the desire to express our individuality. It is easy to understand why self-expression has become so important. Think of the way we use the Internet. If you and I typed the same question into the same search engine, we would be presented with an identical list of web entries, but would probably choose to explore different ones, in different sequences. Once we had checked out a particular entry, each of us might decide to flit off into another blog or website, doubtless different ones again. We may end up with the same answer, but we would be unlikely to have found it in the same way. Even if you personally put the same question to the same search engine on different days, the results could be equally diverse. The way in which you choose to analyse the available information would depend on your mood, the amount of time you had to spend on the search and how preoccupied you were with other matters. Every time we use the Internet, we determine our own idiosyncratic paths around it, picking a route, deviating from it at will and ending it at random, having pieced together the information bit by bit.

We determine our own destinies in video games too, and in the experience of conceiving, planning, designing and constructing virtual worlds in games like The Sims and Spore, or online environments such as Second Life and YoVille. We spin our life stories on Facebook, comment on them on Twitter and illustrate them on Instagram. When we write an email, print a letter or read an ebook, we expect to choose which size and style of font to use, turning some of us into amateur type buffs. (Hence the outcry when IKEA abandoned the purist modernist font Futura in its corporate logo for the digital typeface Verdana.7) If we do not like the look of a website, we can redesign it with an app like Readability, and do the same on an iPad with Instapaper.8 And we are rapidly becoming accustomed to redesigning all – or parts – of ourselves. If you do not like a photograph of yourself, you can digitally erase the offending features, or you can achieve similar effects for real with cosmetic surgery, prostheses, hair dye, wigs, coloured contact lenses, make-up and other extreme, and not so extreme, ‘beauty’ treatments.

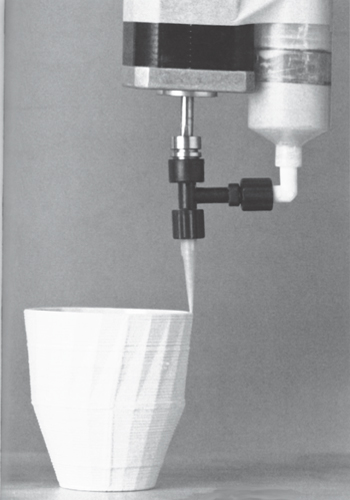

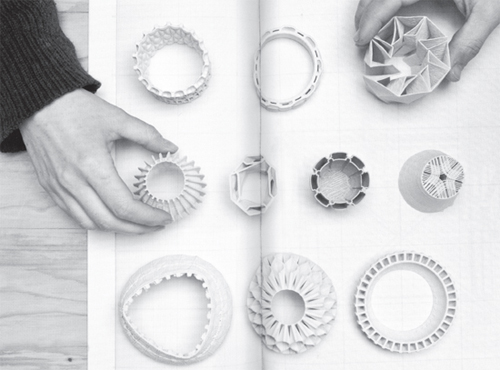

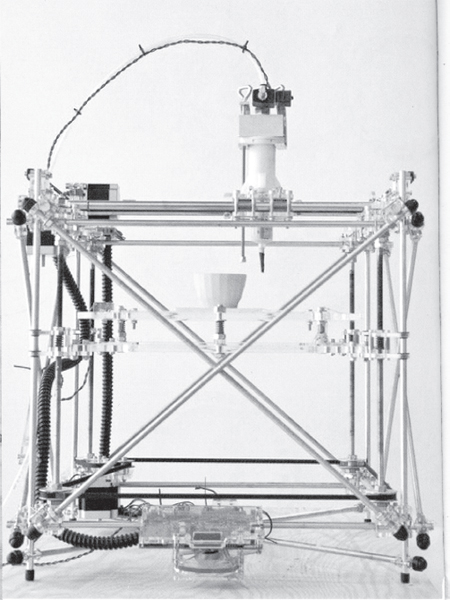

Unfold’s experiments with 3D printing technology

The outcome is that we are increasingly eager to take design decisions ourselves, rather than delegating them to designers. Not that personalization is new. Wealthy people have always been able to pay for things to be designed and made specially for them, as Qin Shihuangdi did by orchestrating his fantastical afterlife and Louis XIV by founding Gobelins as a personal luxury-goods production plant. At the other end of the economic scale, the poor often have no choice but to fend for themselves. Wherever you go in the world, you will find inspiring examples of the ‘necessity is the mother of invention’ principle of design ingenuity. The roads of Asian and African cities are filled with rusty bicycles that have been converted into ersatz trucks and people carriers. Farmers have protected their land for centuries by constructing drystone walls from stones they have found on nearby land. A well-built wall can last for decades, marking boundaries and providing shelter for wildlife, as well as for the insects, mosses and lichen that live among the stones.9

In developed economies, customization was the norm for rich and poor alike until the Industrial Revolution, when mechanization made it possible to manufacture huge quantities of standardized objects more cheaply and efficiently than producing them individually. At the time, uniformity seemed seductively new, which is one reason why late eighteenth-century socialites were so besotted by Josiah Wedgwood’s factory wares. Standardization felt even more alluring to early twentieth-century modernists, for whom it was no longer a novelty but seen as a means of building a better future. Their optimism was shared by the management theorists of the day, notably the American engineer-turned-author Frederick Winslow Taylor. Having declined a place at Harvard to become an apprentice machinist, he rose up the ranks of a Philadelphia steelworks by spotting clever ways of improving its operations. Taylor distilled what he learnt there in his 1911 book The Principles of Scientific Management, which proposed standardizing every aspect of management and production, including the design of the finished products.10 Among his admirers was a young Detroit automotive engineer Henry Ford, who put Taylor’s principles into practice at the Ford Motor Company, where he defined the ‘Fordist’ formula for running an efficient assembly line by combining standardized design and production – just like Qin’s weapon makers – with relatively generous wages for his workers and competitive prices for the cars.11 ‘Any customer can have a car painted any colour that he wants so long as it is black,’ said Ford, after discovering that waiting for the paint to dry took up more time than any other part of the manufacturing process, and that black was the fastest-drying shade.12 Such ploys helped the price of the Model T Ford to fall from just over $800 in 1908 to $250 in 1919, making it affordable for most skilled workers in the United States.

Over half a century after the publication of Taylor’s book, the legacy of Fordism could be seen in a 1965 film of Martha and the Vandellas performing their single ‘Nowhere to Run’ on the Mustang production line at Ford’s huge Baton Rouge plant. The manufacturing process continued uninterrupted while Martha Reeves, Rosalind Ashford and Betty Kelly sang the song. Dancing past a row of painters aiming spray guns at panels of the cars, they jumped into a half-built Mustang on a hydraulic assembly line. Clicking their fingers, they sang from the car’s seats while the workers put panels into position, fitted wheels and winched in the engine. By the time the song ended, the car was finished and Martha and the Vandellas jumped out, making way for its delighted ‘owner’. They waved him off as he drove away in his new Mustang. The song lasted for less than three minutes.13

By then, the corporate enthusiasm for standardization was reinforced by the official edicts of national standards institutes, safety regulators and consumer watchdogs, as well as a labyrinth of legislation imposed by individual countries and international bodies such as the European Union to regulate the size, weight, density, power and other facets of countless products and services. The benefits have been immense, not only by giving millions of people access to cheaper products, but by making many of them safer, more efficient and less damaging to the environment.

The downside is that standardization can also make our lives seem soulless. Take the colours of the fabrics used to upholster the chairs designed by Charles and Ray Eames in the post-war era. When Hella Jongerius analysed the colours used by Vitra, which manufactures the Eameses’ furniture in Europe, she noted that technically they were the same shades specified by the designers years before, even though they looked subtly different. The hues of the original fabrics were slightly variegated, which made them appear warmer and more nuanced. Vitra’s technicians had continued to use the same colours, but they had gradually become more homogeneous as the chemical specifications of the dyes and finishes were tweaked to comply with changes in safety regulations. Jongerius’s solution was to combine marginally different versions of the same shades to recreate the original effect.14

Compared to improved safety, greater reliability and the other practical advantages offered by standardization, marginally duller furniture is a minor concern. But even tiny issues like this can grate in an age when, having enjoyed the benefits of standardization for so long, we take them for granted, and yearn for idiosyncrasy. The popularity of vintage fashion, the revival of interest in craft and folklore, and the fad for dangling trinkets from mobile phones are all attempts to stamp our personalities on our possessions, as are the crazes for ‘hacking’ tech products by modifying them and ‘steampunking’ objects by presenting them in fantastical, antique guises. And professional designers have become adept at finding ways of enabling us to personalize the things that fill our lives on a larger scale by assuaging our desire for individuality, without sacrificing the practical benefits of standardization.

Sometimes, it is enough simply to give us the impression that an object is unique. Hella Jongerius designed the various patterns on her Repeat upholstery fabric for the American textile company Maharam so that none of them would be repeated for long enough to spoil the illusion that each length of cloth is distinctive. She also programmed the production process of her B-Set dinner service to add tiny flaws to the glazing. After decades of industrial ‘perfection’, those glitches look so incongruous that we associate them with the charming quirks of handcrafted ceramics even though they are identical on each piece.15 The Japanese retailer Muji achieves a similar effect, by omission, not inclusion. The name Muji is an abbreviation of mujirushi, which means ‘no brand’ in Japanese, and there is no visible branding on its products.16 Once you have bought something from a Muji store and removed the price sticker, all traces of its origins disappear, and it feels as though that product really is yours.

A similar transition has been made in architecture. In Farshid Moussavi’s book The Function of Form, she describes how Mies van der Rohe applied Fordist principles to the construction of buildings by using the then-innovative method of steel frame construction.17 He also experimented with different configurations of prefabricated steel components to open up the interiors to their surroundings: the frenzy of New York’s streets in the case of the Seagram Building on Park Avenue, and the natural beauty of the Czech countryside for Villa Tugendhat in Brno.18 Towards the end of his career Mies was criticized for repeating similar forms, specifically in the Bacardi Building in Bermuda and the Neue Nationalgalerie in Berlin. He replied by stating that he ‘refused to design a new architecture every Monday morning’. Whereas Rem Koolhaas’s practice OMA conceived the China Central Television headquarters in Beijing so that the building would never seem quite the same. If you look at the structure, it appears to distort slightly each time you change the angle at which you are seeing it, or move closer towards it, or further away. As a result, whenever you see the building it feels intensely personal because you know that no one else, not even you, will ever observe it in quite the same way again. Impossible though it seems for something as massive as the CCTV building to move or morph, the complex geometry of OMA’s design fosters the impression that it does just that.19

In the 1960s and early 1970s, the avant-garde architecture group Archigram sketched fantastical projects like the Plug-In City, which had a limitless capacity to expand or contract as different units were plugged in and out.20 The French brothers Ronan and Erwan Bouroullec have applied similar principles to familiar objects by designing modular products that can be personalized by their users when they add or subtract various elements to change their size or purpose. The Joyn office system that the brothers designed for Vitra was inspired by the long wooden table in the kitchen of their grandparents’ farm in Brittany. At any one time, several people might have been eating at the table while another prepared food and a couple of children pored over their homework. Joyn consists of a series of desks of differing lengths to which screens can be added, to create workstations of varying sizes and provide privacy in open-plan offices and studios. The space allocated to each person can be adjusted whenever people join or leave the team, and the desks cleared to create a conference table for meetings.21

Other designers have deployed software programs to ensure that the same object can be reproduced in an infinite number of ways. Breeding Tables, a project by the Swedish-German design team led by Reed Kram and Clemens Weisshaar, uses computer-controlled laser-cutting technology to create distinctive bases for each of a series of tables. The actual shape is chosen at random by the software.22 A similar principle was applied to My Private Sky, a collection of bespoke plates they designed for the German porcelain maker Nymphenburg. My Private Sky is a set of seven plates that collectively depict an astrological map of the sky on the night when the owner was born. The date, time and place of birth are punched into a computer, which draws a digital map of the hundreds of stars, planets and galaxies in the sky that night to be painted on to the plate by one of Nymphenburg’s artisans.23

An alternative is to introduce a spontaneous element to the development process, as the Slovakian designer Tomáš Gabzdil Libertíny did by delegating the making of his Honeycomb Vase to a hive of forty thousand bees. Having cast solid beeswax into the shape of a conventional vase, he placed it inside a hive, where the bees determined the final shape by adding layer after layer of beeswax on to the mould. Beautiful and unique though each vase is, Libertíny’s template will only ever work on a small scale. The vases have to be made in April, May and June, when the bees are at their most active. Even then, finishing each one can take as long as a week.24

Personalized objects like these tend to be expensive, but there are more affordable approaches. We customize smartphones and computers instinctively, by loading them up with different software programs, apps, files and screensavers. The physical structure of the device remains identical, but the contents of its screen will be distinctive. Even if you and I downloaded the same apps on to our phones, we would arrange them in different ways, according to the frequency with which we expected to use them and where we thought they looked best. Glimpsing the screen of someone else’s phone or computer is akin to reading their diary, or scrutinizing the content of their bookshelves. Why else would lecturers look so embarrassed when their graphic interfaces are accidentally projected on to the screen? Even if the contents are uncontentious, they may prefer not to display them in public: doing so risks revealing more about themselves than they might wish.

Graphic interfaces change constantly, depending on whatever we happen to have parked on our screens at particular times. More than any other aspect of a digital product, it is they that make it feel as if it is ‘ours’, because we have decided what will be seen on them, not the designer or manufacturer – though no graphic interface will feel quite as personal as one containing an app you have designed yourself, as the tens of thousands of mostly self-taught developers of applications have discovered.

The app phenomenon typifies the do-it-yourself spirit that has already fuelled the crazes for tinkering, steampunking, hacking and Maker Faires, and put pressure on even the largest companies to open up their development processes. Once it was deemed the height of corporate chic for products to be developed in deepest secrecy. Steve Jobs relished whipping up speculation about Apple’s product development plans by refusing to disclose details in advance and revealing the finished object to a rapturous audience. Spectacularly effective though it was, corporate mores have changed, and many areas of design have embraced the open source process, whereby the development of a design project is open to public scrutiny for other people to comment on and learn from. Open source design was pioneered in the software industry, partly thanks to the efforts of Dennis Ritchie, who insisted that ‘Hello, world’ and the other programs in C language should be ‘open systems’ that could be used on different types of computers. Ben Fry and Casey Reas have applied open source principles to the development of Processing, as has Poonam Bir Kasturi in her work on Daily Dump.

In the same spirit of transparency, some companies have utilized digital technology to enable customers to personalize their products from the outset. Nike has an online service with which consumers can choose different colours, materials and finishes for sports shoes. If you click on part of a running shoe, such as the heel clip or ankle cuff, a menu flashes up explaining the possibilities. You can change the colours, or pick a translucent sole rather than an opaque one. It is also possible to customize the functional attributes of some shoes, such as soccer boots, whose soles can be given extra cushioning to reduce the pressure applied by the studs, or less cushioning for faster response times.25 Other businesses have used crowd-sourcing techniques to enable their customers to influence the design process, like Local Motors in Arizona, which invites people to contribute ideas to the development of energy-efficient cars.26

The most radical approach to customization is the development of exceptionally fast, precise and flexible digital production processes, such as three-dimensional printing. By rendering it as easy and inexpensive to make things individually or in very small quantities as in very large ones, 3D printing promises to reverse the commercial logic of the economies of scale that has made standardization so profitable since Josiah Wedgwood’s day. The Economist has described it as a transformative technology like ‘the steam engine in 1750 – or the printing press in 1450, or the transistor in 1950’, and predicted that 3D printing could herald the start of a new era of mass customization.27

The first stage of 3D printing is to download the design template for an object on to a computer and to tweak it. Maybe you will decide to change the colour or finesse the shape. Once you have adjusted it to suit your wishes, you press ‘print’ to instruct a nearby 3D printer to make it, and collect the finished piece from there, just as if you were printing a document from a computer. The location of the printer is chosen with your convenience in mind, not the manufacturer’s or designer’s, It makes no difference if it is thousands of miles away from them, or in a neighbouring building. The object is built by adding fine layers of material on top of one another, not unlike the way in which the bees constructed the delicate beeswax structure of the Honeycomb Vase for Tomáš Gabzdil Libertíny. A similar process, known as ‘rapid prototyping’, has long been used to produce highly detailed models of buildings for architects and of cars for automotive design studios. One limitation is that, so far, 3D printing is only suitable for specific types of plastic, resin and metal. Another is that it can make only solid blocks of material, such as an iPhone case, but not its contents. A third constraint is cost. Until recently, 3D printers were too expensive to be used on anything other than an experimental basis, but their prices have fallen significantly and will be even lower in future.

The technology is already being used to customize objects of dramatically different sizes and degrees of complexity. It can personalize simple, everyday products, such as cups and pens, by making stylistic tweaks.28 Other objects can be adapted to make them easier to use by people with physical impediments. If you have arthritic hands, you are likely to have difficulty gripping cooking utensils like knives or spoons. The process can tackle that problem by widening the handles until they are easier to hold. The extreme precision of 3D printing also enables it to produce larger, more complicated components, including aircraft and car parts, which will be capable of withstanding extremes of temperature, weather, speed, weight and tension. NASA has installed a 3D printer in the International Space Station for emergency repairs. These components are often lighter than existing ones, thereby reducing the fuel consumption of the aeroplane or vehicle. Similarly, the technology can be used to make tiny medical devices which need to fit neatly into particular parts of the body, such as hearing aid cases and dental crowns, as well as artificial hips and jawbones. The curvature of a human bone is impossible to replicate using conventional manufacturing techniques, whereas 3D printing can not only match it exactly, but reproduce the lattice-like internal structure to create an implant which is stronger, lighter, and sits more comfortably inside the body. As a result, it also promises to transform the production of prostheses, like Aimee Mullins and Hugh Herr’s artificial legs.

As the technology advances, it will be possible to apply it to a wider range of materials and objects. And as the cost of 3D printers falls, they will appear in more and more places, where many more people will have access to them. Eventually, they could be installed in villages and towns all over the world for the local communities to use.29 For centuries, people would go to a nearby blacksmith’s forge to have things made or repaired; in future they may do the same at a nearby 3D printer. Similarly, construction projects need no longer be held up if there is a delay in delivering an important part, or a faulty one needs to be replaced, because the specifications can be sent immediately to the closest 3D printer.

The growing use of such processes is likely to have an aesthetic impact on the products that fill our lives. Just as leaps in design and construction software have enabled architects such as OMA, Zaha Hadid, SANAA and Farshid Moussavi to construct buildings in complex forms, 3D printing will develop a new vocabulary of shapes for objects.30 These three-dimensional versions of the eerily intricate digital forms we see on our computer screens will be the contemporary equivalents of other shapes that have come to dominate design whenever new technologies have enabled designers to produce something different: the smooth geometry of 1920s ‘machine age’ furniture; the luscious curves of 1960s plastic ‘pop’ pieces; and the ubiquitous ‘blobs’ that defined product design in the 1990s when some designers got carried away with their newly acquired design software. The work of OpenStructures, Unfold and other design groups committed to developing new ways of working with new production technologies suggests that the surreal aesthetic of 3D printing will also be adept at reflecting the cultural shift away from the twentieth-century illusion of clarity and uniformity by expressing the contradictions and inconsistencies of human nature,31 as conceptual designers like Anthony Dunne and Fiona Raby have done in their experimental projects.

Design has already influenced the early development of 3D printing, and its contribution will become increasingly important as the technology evolves. A critical challenge for industrial design is to ensure that manufacturers and consumers are able to make the most of the practical benefits of such processes to develop products that are more efficient, less expensive, more durable and better suited to their users’ needs. Impressive though all of that sounds, 3D printing also offers an important opportunity to make progress on the sustainable front.

If the only material used in the manufacturing process is the exact quantity needed to make the object in question, there will be no waste, which is not only beneficial environmentally, but financially too because it reduces the risk of manufacturers wasting money on superfluous raw materials. Similarly, if more products are ordered on a bespoke basis, there will be less need for manufacturers and retailers to carry stock which could end up being scrapped should it remain unsold. Nor will it be necessary for them to ship as many products or components from far-flung subcontractors to warehouses and stores, thereby saving fuel. Each product can also be expected to last for longer because repairs will be simpler. All in all, there should be substantial savings in energy, materials and other resources, with tremendous environmental benefits.

The possibility of making products in tiny quantities also promises to usher in a new era of experimentation, as designers and manufacturers become increasingly confident about testing new or unusual ideas. They will be able to gauge the response to a few pieces, or to variations of a design proposal, before making the hefty investment required to put them into volume production, if they still consider that to be necessary in the dynamic new age of ecologically smart customization.