Following a series of shootings, the Seattle City Council discussed the city’s response at a public meeting on May 29, 2012, with police officials. At the meeting, Seattle City Council member Tom Rasmussen found nothing new in the police department’s proposals to address the violence, observing, “I have some skepticism about whether this will have any effect. We have seen many community vigils, community mobilizations. We’ve heard about these strategies before. What’s going to change?”1

The very next day, Seattle was hit by yet another all-American shooting rampage. This mass murder was at a “quirky Seattle hangout,” a coffee shop and bar known for its “eclectic music and friendly vibe.”2 The latest murders struck at Seattle’s historic association with popular music. Ray Charles played at jazz clubs and made his first recording in Seattle. Jimi Hendrix, a Seattle native, got his start there. Decades later, the grunge era of the 1990s launched Nirvana and other bands.3 The New York Times noted in 2010 that “a growing number of young musicians have been focused on building an autonomous scene, something distinctive and homegrown.” One of these young musicians’ venues was Café Racer, “distinctly postgrunge, with its scuffed floor and mismatched furniture, its thrift-store paintings on boldly colored walls.”4 The cafe is also the “Official Bad Art Museum of Art (OBAMA)” where one can “gaze in wonder at the astounding paint-by-number and black velvet paintings.”5

The whimsy ended just before eleven A.M., Wednesday, May 30, 2012, when Ian L. Stawicki, holder of a concealed-carry permit, walked in. Stawicki, forty, had been thrown out of Café Racer previously and banned because of his “loud, bizarre behavior.”6

This erratic behavior—the hallmark of all too many of America’s concealed-carry killers—was familiar to Stawicki’s family. His father said Ian had suffered from mental illness for years and his behavior had gotten “exponentially” more erratic. He claimed his son enlisted in the U.S. Army after high school but lasted only about a year before getting an honorable discharge.7 (An army spokesperson said it had no record of Stawicki’s having served.8) In any event, the family failed to convince Ian to seek help. Those who knew Stawicki said his life’s history was “dotted with clues, including failures, social rejection, episodes of apparent delusions, spasms of violence and a strong interest in guns.”9 None of this stopped Stawicki from getting his “shall issue” concealed-weapons permits from Seattle and Kittitas County10 Nor did it prevent him from legally buying three 45 caliber and three 9mm semiautomatic pistols.11

The familiar combination of a mentally unstable person legally carrying concealed handguns had its predictable result. Sixty-three seconds after Stawicki—with two 45 caliber pistols in his pockets—walked into Café Racer and was refused service, he had shot four people to death and critically wounded another. Stawicki paused to steal a “bowler style” hat from one of his victims, then left. By 11:30 A.M., he had confronted a businesswoman in a parking lot, shot her to death, and fled in her Mercedes-Benz SUV. He gave “the finger” to bystanders coming to her aid.12 Police cornered Stawicki at around four P.M. He knelt on the sidewalk and shot himself fatally in the head.13

The familiar public ritual commenced. “The city is stunned and seeking to make sense of it,” Mayor Mike McGinn said. “I think we have to start by acknowledging the tremendous amount of grief that’s out there from the families and friends of the victims.”14

Yet one of the purposes of this book is to ask the uncomfortable question: How are rituals of community healing, however heartfelt, going to stop the violence with which the gun industry is polluting America? How are makeshift memorials of candles and teddy bears going to stem the flood of militarized killing machines—assault weapons and high-capacity semiautomatic pistols—that abound in every community in America?

The sad but self-evident truth is that the fleeting ritual embrace of public sorrow is not action. At best, these moments of public ritual give the image-hungry media a few seconds of self-conscious sentimentality, and they give policy makers safe platforms to strike “caring” postures. Memorial events are tough-question-free zones. Eventually the cameras leave, the plastic flowers fade, the stuffed toys rot. And in the end, nothing has changed.

At worst, these weepy rituals play into the hands of the gun industry and its lobby. After major shootings, the NRA, the gun industry, and their cohorts suffocate any discussion of effective policies to stop gun violence. They piously argue that “now is the time to mourn.” Their self-righteous surrogates pretend that it is disrespectful to discuss gun-violence prevention while families and survivors are grieving—regardless of the fact that it is often fellow victims and survivors from prior attacks who make such demands. No one in his or her right mind would dream of making such a foolish argument in the wake of the crash of a passenger jet. Or after a terrorist attack.

The blizzard of gun violence documented in this book is not a “gun safety” problem. Nor is it a problem of legal versus illegal guns. It is a gun problem. It is the direct and inevitable consequence of the gun industry’s cynical marketing, the proliferation of lethal firepower, and the waves of relaxed state laws—concealed carry, shoot first, shoot anywhere, shoot cops, just shoot, shoot, shoot—that the gun industry’s handmaiden, the NRA, has inflicted on the country to promote new markets for the industry.

How can it be that Americans tolerate this relentless slaughter, when they have willingly spent trillions of dollars and surrendered their dearest constitutional rights to protect themselves against the comparatively minuscule threat of terrorist attack? One explanation might be that Americans simply don’t care about gun violence or its victims—until it strikes them, or their families, or their neighbors, or their co-workers, or the people they worship with, or the artists they create with or listen to. In truth, some clearly do not care. Hypnotized by sepia-tinted fables of “gun rights” and socially impaired by their lack of empathy, they believe that no sacrifice is too great for others to bear so that they can enjoy unbridled access to their deadly toys, their lethal security blankets, and their pretended defense of liberty. The pro-gun writer and advocate Dave Workman, for example, “a loyal foot soldier in the pro-gun publishing and lobbying empire of convicted felon Alan Gottlieb,”15 uttered an incredibly thick-witted explanation to the local NPR affiliate in Seattle following the Café Racer shooting. Nothing can be done, Workman argued, because the rest of us must respect the choices of gun-toting misfits like Ian Stawicki. “We can’t treat him like a child, he’s got his own life to live and he can make his own mistakes no matter how horrific those mistakes turn out to be.”16

But most Americans do care about gun violence. They want change. What they lack first is information about its true dimensions and causes. The media whiteout and the gun industry lock-down of data leave Americans so poorly informed about how common and widespread gun violence is that they are surprised when it strikes them and often write it off to mere chance. They ignore the contradictions inherent in their own observations about the more frequent types of gun violence, such as how the previously law-abiding shooter “seemed like such a nice person, we would never have thought he would do such a thing,” or “things like this just don’t happen in our community.”

From policy makers, the press, and self-appointed experts, we are often presented with statements and plans of action that reinforce common misperceptions about gun violence instead of challenging them. The result is that America lacks a clear national plan of action to significantly reduce gun violence. The essential elements of such a plan are fact-based public health action programs that have been proven effective over decades. “In 1900 the average life expectancy of Americans was 47 years,” David Hemenway, director of the Harvard Injury Control Research Center and the Youth Violence Prevention Center, wrote in his 2009 book about the public health approach. “Today it is 78 years. Most of this improvement in health has been due to public health measures rather than medical advances.” Hemenway explained that “the concern of public health is to improve the health of societies,” and its focus is “not on cure, but on prevention.”17

Motor vehicle safety—which most Americans now take for granted—is a prime example of fact-based public health action. Between 1966 and 2000, the combined efforts of government and advocacy organizations reduced the rate of motor vehicle death per 100,000 population by 43 percent. This represents a 72 percent decrease in deaths per vehicle miles traveled.18 And as a direct result of these public health measures, motor vehicle death and injuries continue to decline. In 2010, the number of fatalities in motor vehicle traffic crashes was 32,788—the lowest level since 1949. This drop took place despite a significant increase in the number of miles Americans drove.19

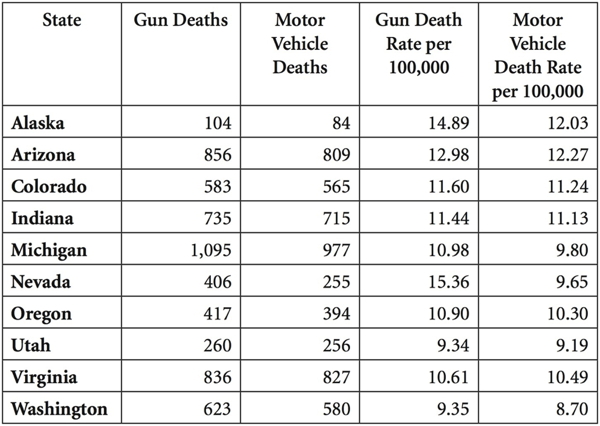

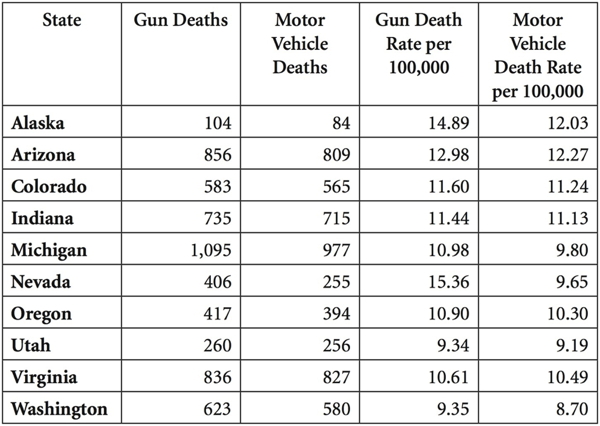

Yet as motor vehicle-related deaths have declined, firearm deaths have continued unabated—the direct result of the failure of policy makers to acknowledge and act on this ubiquitous public health problem. In shocking point of fact, gun fatalities exceeded motor vehicle fatalities in ten states in 2009. In that year, as figure 11 shows, gun deaths outpaced motor vehicle deaths in Alaska, Arizona, Colorado, Indiana, Michigan, Nevada, Oregon, Utah, Virginia, and Washington.20

What is the difference? It is that firearms are the last consumer product manufactured in the United States that is not subject to federal health and safety regulation. As Hemenway explained in another book, “The time Americans spend using their cars is orders of magnitudes greater than the time spent using their guns. It is probable that per hour of exposure, guns are far more dangerous. Moreover, we have lots of safety regulations concerning the manufacture of motor vehicles; there are virtually no safety regulations for domestic firearms manufacture.”21 Examples of federal agencies and the products for which they are responsible include: Consumer Product Safety Commission (CPSC), household products (except for guns and ammunition); Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), pesticides and toxic chemicals; Food and Drug Administration (FDA), drugs (including tobacco) and medical devices; and the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA), motor vehicles.

Figure 11. Firearm Deaths Exceeded Motor Vehicle Deaths in Ten States in 2009

In 2009 there were 31,236 gun deaths nationwide for a rate of 10.19 per 100,000 and 36,361 motor vehicle deaths (both occupant and pedestrian) nationwide for a rate of 11.87 per 100,000 (both totals include data only for the fifty states). WISQARS database, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Before the advent of the public health approach, the focus in motor vehicle safety was on changing the behavior of the “bad driver” or “the nut behind the wheel,” and it had limited results.22 The establishment of NHTSA in 1966 marked a distinct change. It was part of a sustained decades-long public health effort to develop and implement a series of injury-prevention initiatives that work and have saved countless lives. These public health initiatives made changes in both vehicle and highway design. Vehicles incorporated such new safety features as better headlights and brakes, head rests, energy-absorbing steering wheels, shatter-resistant windshields, safety belts, and air bags. Roads that vehicles travel have been improved by more effective marking of curves, use of breakaway signs and utility poles, better lighting, barriers separating oncoming traffic lanes, crash cushions at bridge abutments, and guardrails.23 Experts also cite the increase in the use of seat belts, beginning in the mid-1980s as states enacted belt-use laws, and a reduction in alcohol-impaired driving as Mothers Against Drunk Driving and other organizations changed the public’s perception of the problem and laws were enacted to increase the likelihood that intoxicated drivers would be punished. Graduated licensing laws are credited with helping to reduce the number of teen drivers crashing on our nation’s roadways.24

It is extremely important to note that the creation of NHTSA’s comprehensive national data system was a vital part of this success, because it “enabled scientists to determine the main factors affecting road safety and which public policies were and were not effective.”25 Pioneers in vehicle safety “insisted that the injury field be based less on opinion and more on science.”26

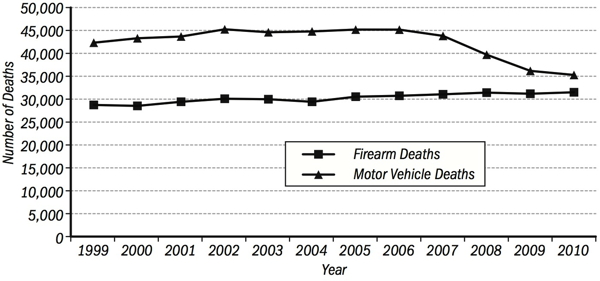

America’s failed approach to gun death and injury has been the exact opposite of what has been proven to save lives in hundreds of other fields. Data and information have been shut down. Driven by ideology, triangulation, and flatly misinformed opinion, attention remains focused on “bad people” and exaggerated “rights,” not on the greed of the gun industry and on the reckless features of its militarized products—guns that hitherto “good people” use dozens of time a day to kill each other and themselves. The result is that, although more than 90 percent of American households own a car,27 and fewer than a third of American households contain a gun,28 the year-by-year trends of deaths nationwide from these two consumer products are on a trajectory to intersect.

These trends will be encouraged for the worse as the gun industry and the NRA—with the compliant support of many state legislatures—continue to weaken gun control laws in order to hype markets for their deadly products. The reason for the gun industry’s frantic efforts is the handwriting that they have seen on the wall. Not only is gun ownership declining in America, it is in free fall among younger cohorts. In the 1970s, approximately 45 percent of respondents under thirty years of age reported that their household owned a gun. Recent surveys have shown that number now to be below 20 percent, a decline of more than half.29 As one author observed:

Barring a wholesale return to rural living or a boom in hunting, it seems unlikely that this trend will reverse. Demographic diversity will also likely contribute to a continued decline in gun ownership. White males own guns at higher rates than members of other groups, while gun ownership among African-Americans is lower, and ownership among Latinos and Asians is lower still. Every projection by demographers shows whites declining as a proportion of the American population in the next few decades, and Latinos are now the country’s largest and fastest-growing minority group. These factors will likely produce a continued, if not accelerated, decline in gun ownership.30

Figure 12. Firearm and Motor Vehicle Deaths 1999 through 2010

But there is no reason to simply wait for demographics to erase the American gun industry. Hundreds of thousands of lives are literally at stake if we do nothing while the gun industry strikes out more and more dangerously, like a wounded rattlesnake in its final throes. There are a number of specific things that can and ought to be done by all Americans who want to see gun violence drastically diminished—and specific groups like activists in all progressive causes, policy makers, the media, foundations, and public health practitioners:

1. Stop accepting excuses from politicians. Americans who care about gun violence need first to take back control of this issue from those politicians who refuse to act forcefully. Politicians who are leaders on gun violence prevention are the exception, not the norm—despite the effects guns have on citizens in every state in the nation. The NRA and the gun industry control this issue because the majority of politicians we elect (and reelect) let them control it. The cries of the victims of gun violence are muffled by poll-driven positions and the comfort of accepted political wisdom of those ensconced in their golden triangle.

The degree to which the gun lobby can control the political debate was starkly illustrated in August 2009 at a White House press conference. During that month, a spate of armed protestors began showing up at presidential events. In Portsmouth, New Hampshire, a man with a gun strapped to his leg stood outside a town hall meeting with a sign reading, “It’s time to water the tree of liberty”31 The reference was to a letter in which Thomas Jefferson wrote, “The tree of liberty must be refreshed from time to time with the blood of patriots and tyrants. It is its natural manure.”32 In Phoenix, Arizona, about a dozen people carrying guns, including one with an AR-15 assault rifle, milled around among protesters outside the convention center, where the president was giving a speech. A spokesman for the Secret Service admitted that incidents of firearms being carried outside presidential events were a “relatively new phenomenon,” but insisted that the president’s safety was not being jeopardized.33

But, one might fairly have asked, what about the safety of other ordinary citizens who aren’t carrying guns and don’t want to carry guns? What about their rights, and their preferences? What about the intimidation inherent in the open display of guns at political events by people who are, to put it mildly, clearly angry? What will be the effect of this precedent on future presidents—and other public figures? What about the possibility of people showing up with more advanced firepower—such as freely available 50 caliber antiarmor sniper rifles?

When asked about these events, White House Press Secretary Robert Gibbs spoke only to the parochial interests of gun enthusiasts, saying merely that people are entitled to carry weapons outside such events if local laws allow it. “There are laws that govern firearms that are done state or locally,” he said. “Those laws don’t change when the president comes to your state or locality.”34 But as the commentator E.J. Dionne incisively observed at the time, Gibbs’s technical response missed the bigger point. “Gibbs made you think of the old line about the liberal who is so open-minded he can’t even take his own side in an argument. What needs to be addressed is not the legal question but the message that the gun-toters are sending.”35

It was a “teachable moment.” But instead of using these events as an opportunity to speak out about “the message that the gun-toters are sending,” Gibbs’s meek response only validated their threatening actions, further empowering them. Americans must demand that such appeasement of the gun industry and extremist gun enthusiasts end.

2. Demand an end to the lockdown on gun and gun violence data, and insist on the creation of comprehensive databases and open information about guns and gun violence. Chapter 7 demonstrated how the gun industry and its accomplices in Washington have locked down data and information about guns and gun violence. But data and information are essential to the public health approach, to assessing which policies work to reduce death and injury and which do not. It is fundamental to understanding virtually every firearm-related issue—including the effects of concealed-carry and shoot-first laws, the role of assault weapons, traffic in guns abroad, the effects of guns in the home, and more.

Americans, including activists and especially including policy makers, need to understand that the true reason behind this information lockdown is simply and completely protecting the gun industry from accountability for its depredations. The shameful argument that withholding tracing data protects law enforcement officers and the integrity of investigations is plainly fraudulent.

All of the so-called Tiahrt restrictions on crime-gun data should be ended. But much more needs to be done. The federal government should create a comprehensive reporting system—preferably separate from the weak and compromised ATF—that gathers and integrates in one system data about every aspect of firearms and their use in America. Public health analysts, policymakers, and ordinary citizens should be able to find out as much about the trends in gun violence as that which is freely available today about trends in tire blowouts, baby stroller design, tainted foodstuffs, and virtually every item of consumer usage. The industry will argue that such a database would make it possible to compile the wholly imaginary but nonetheless dreaded “national list of gun owners,” a supposed prelude to “confiscation.” This argument is an extension of paranoia beyond all reason but an excellent fund-raiser for the NRA and others who trade in fear, loathing, and paranoia. If the argument must be taken seriously, it would not be at all difficult to craft a system of data collection and retrieval that would yield the necessary data without including any details of individual ownership.

In the meantime, local activists should aggressively find and pursue sources of data about guns and gun violence in their communities and states, compile it as best they can, and regularly make the information available to the news media in creative reports. These sources include public information such as state Uniform Crime Reports (UCR) data, information from states that participate in the National Violent Death Reporting System (NVDRS) and other statewide information-gathering systems, medical examiners’ records, police and court records, legislative hearings, and local government action. This also includes developing personal contacts with people in the community whose work brings them into contact with incidents of gun violence.

3. Understand that gun violence is not “someone else’s” issue. Gun violence is not an issue just for gun violence prevention activists. Gun violence affects virtually every community—socioeconomic, racial, ethnic—in America, not to mention workplaces, schools, shopping centers, and children’s soccer games. Moreover, the gun lobby and gun industry are supported by the agenda of a well-funded, well-organized rightwing coalition. Groups and people who work on the progressive side of issues of domestic violence, school safety, youth violence, and drug abuse, for example, or who work in minority communities should understand that the gun industry, guns, and faux “gun rights” are the ultimate drivers of many of the problems they face. It is their issue too. What is needed is a much grander, better-informed, and better-funded coalition.

Funders—from the largest foundations to the smallest individual donors—and policy makers need to understand that these issues cannot be walled off from each other. For example, guns from the United States empower the criminal organizations in Latin America that produce most of the drugs sold on our streets. Guns empower the organized gangs that sell these drugs at retail in the United States. And guns are often used in the domestic violence that breeds in families and communities shattered by drug abuse.

4. Learn about guns and the gun industry. Gun control may be one of the few issues in America in which all opinions, no matter how under- or misinformed, are given equal weight. Few things are as disheartening as listening to a longtime advocate or well-intentioned policy maker talk about guns and the gun industry in a way that makes it clear that she or he has not done the homework. Expounding on assault weapons, for example, without understanding the specific design features that distinguish them from sporting rifles (or fully automatic machine guns) and make them so dangerous does more harm than good.

And yet there is nothing all that complicated about how guns work or how the industry operates. It’s not rocket science. Those who want to be involved in this issue should educate themselves about the underlying facts before expounding on solutions. The Violence Policy Center (vpc.org) and other organizations, as well as leading researchers, have posted dozens of monographs online that explain in detail virtually every issue in gun control. These reports and studies contain voluminous notes about the sources on which they are based. They are nothing less than a free university for advocates.

A corollary to this is “know your enemy.” Join the National Rifle Association and read their magazines if you plan to become an advocate. Just as most Americans have no idea what the gun industry has turned into, few understand what today’s NRA represents. The conspiracy theories and venom that reside between the covers of its activist publication, America’s 1st Freedom, would leave most Americans torn between laughing and crying. I hope they’d get angry and take action.

5. Look upstream for gun violence prevention measures. Once vehicle safety advocates stopped trying to reform people and started looking at the actual designs of vehicles and roads, enormous strides were made in saving lives and preventing injuries. This is precisely what needs to be done to turn around America’s gun violence problem. We need to prevent injury before it happens. To do that, we need to look upstream at the gun industry, its products, and how they are distributed.

Policy makers need, for example, to look at what impact the designs of specific guns have on their use. What, for example, is the effect on death and injury of the proliferation of higher-caliber handguns in smaller sizes? This cannot be divined from the gun industry’s or the NRA’s self-serving assertions. If the gun industry insists on calling semiautomatic assault rifles “modern sporting rifles,” let them. But collect detailed data about make, model, and caliber of guns—their sales and their use in crime and other forms of gun violence. A database that includes all the details of incidents of gun violence—similar to databases on contaminated drugs, automobile crashes, and injuries from defective children’s furniture—would yield invaluable information, no matter what label the industry chooses to use in its marketing programs. The gun industry’s marketing and distribution programs, coupled with the increasingly lax laws about access to guns, are the equivalent of the badly designed, dangerous, and poorly marked roads before the advent of the vehicle safety public health approach. The crazy-quilt system that currently purports to regulate the manufacture, import (and smuggling) into and out of America, and sale or transfer of guns within America is clearly ineffective. It benefits no one but the gun industry.

6. Learn from successful programs. One of Wayne LaPierre’s stock horror stories is that some eggheads in America think that we might learn something about gun control from other nations of the world. He’s right. We can learn a lot from the successful experiences of other free and industrialized countries, including those that have sprung from the Anglo-Saxon heritage of which the NRA and the right wing are so protective. Other countries do not suffer the same torrent of needless gun death and injury for the simple reason that neither their citizens nor their leaders will tolerate it.

Moreover, some states in America have succeeded in implementing reasonable and effective gun control programs. In California, for example, key stakeholders—including the foundation community, the gun violence prevention movement, and sympathetic lawmakers—decided to take on the gun lobby directly after a shocking series of high-profile shootings. They broke the gun lobby’s grip on California politics. California is also a good example of how the first round of legislation may not solve a problem, and therefore continued work is necessary. The California assault weapons law was not perfect when it first went into effect, but advocates continued to study how it was working, how the industry was evading it, and what changes were needed to make it effective. In the face of ongoing industry attempts to subvert the law, these efforts continue to this day.

These ideas are intended to suggest taking a different approach to the problem of gun violence—not a third way, not a fourth way, but the right way. America will get the kind of gun violence prevention programs that it deserves only when, and if, the vast, silent majority realizes that strong and effective fact-based policies that significantly reduce gun death and injury are in their interest—and then does something about it.