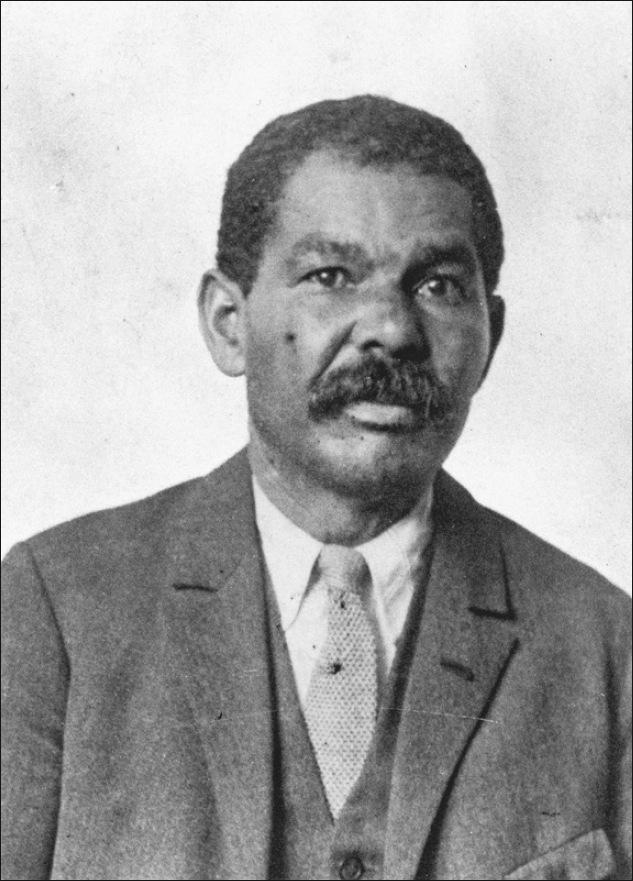

Langston Hughes, c. 1924. Portrait by James L. Allen (illustration credit 3)

Langston Hughes, c. 1924. Portrait by James L. Allen (illustration credit 3)

I’ve known rivers:

Ancient, dusky rivers.

My soul has grown deep like the rivers.

Nineteen years old, Langston Hughes published “The Negro Speaks of Rivers” in the June 1921 issue of The Crisis. For the first time, his work appeared in a national journal. In a real sense, his career as a writer had begun. “The Negro Speaks of Rivers” would become his signature poem. He usually chose it to end each of his many public readings in the years to come.

In September of that year, Hughes arrived in New York City to attend Columbia University. He did so with financial support from his father, who had suddenly reentered his life in 1919 after many years of estrangement. Soon after his birth in Joplin, Missouri, in 1902, his father moved to Mexico. An attempted reconciliation in Mexico failed, and Hughes’s parents divorced when he was five. With his mother often away, he spent most of his childhood in the care of his grandmother in Lawrence, Kansas. After her death in 1915, he joined his mother and her second husband in Lincoln, Illinois, and then in Cleveland, Ohio. There he attended Central High School (1916–1920), where he published his first poems and stories in the school magazine. In 1921, after a year living with his father in Toluca, Mexico, following his high school graduation, he set off to attend Columbia.

Hughes lasted only one year (1921–1922) at Columbia, which he found generally unfriendly, before withdrawing from the school. He then worked at various odd jobs, including delivering flowers in Manhattan and as a gardener on a vegetable farm on Staten Island. He also sought out members of the African American community in Harlem, which later would become central to his life. From 1921 until 1923, living in or near New York City, he worked steadily at his verse even as he befriended other gifted African American writers such as Jessie Fauset, Countee Cullen, and Alain Locke of Washington, D.C.

TO JAMES NATHANIEL HUGHES [ALS]

[On Hotel America, 145-155 West 47th Street stationery]

September 5, 1921

Dear father:1

I arrived last night after a fine trip. The sea was very calm all the way and none of the passengers were sea-sick so we enjoyed the voyage. I am here at the Hotel America for a day only as the boat arrived so late yesterday that the inspection was not passed until nearly 10 P. M. and, not knowing New York, I came here with a number of other travelers from Mexico and Cuba as this Hotel is the center of Spanish speaking travelers. This morning, however, I found a room at the colored Y.M.C.A. at 181 West 135th St. where you can write me, Room 422. I shall not stay there long if I can find any place cheaper as they charge $7.00 a week, but the secretary tells me that it is difficult to find anything much cheaper in a decent house as Harlem is very crowded and those having rooms to rent charge high. He will help me, tho, to find another place, unless I can enter the school dormitory soon. Today being Labor Day the University is closed so I can find out nothing until tomorrow, when I shall go up there, however, send my mail to the Y.M.C.A. address until I get in school and if there are any letters in Toluca2 for me send them, too, please. I will write you again tomorrow giving you the name of a bank where you may send the money and tell you whether I am to be admitted or not.

Mr. Medina was at the docks with me in Vera Cruz. His brother was to leave for Spain on the 1st of this month.

Write soon.

TO JAMES NATHANIEL HUGHES [ALS]

Oct. 6, 1921

Dear father,

I have received no letters from you whatever since being here. The one in which you say you sent the money has not been received in New York according to the Post Office. After paying my preliminary fees and a twenty-five dollar deposit on my dormitory room for ten days, which was up yesterday, I had nothing left to pay on my tuition and the balance due on my room which I was lucky enough to get. Expecting to receive money from you at any moment I procured a postponement of payment until Oct. 3 and then when nothing came had to ask for another postponement until Wednesday when my dormitory fees were also due. I sent you a telegram on Saturday and another on Tuesday from which I received no answers, so, unable to wait any longer, I called upon Mr. C. L. Rossiter3 at his offices, explained matters, and he was kind enough to send a check for $100 and a personal letter to the school asking them to grant me another postponement, which they did until Oct. 20. The money loaned by Mr. Rossiter covered my dormitory fee and $37.50 of my tuition, leaving $120.50 to be paid. I was also compelled to borrow $10 from a person I met here in order to eat and buy the most necessary books, altho there are several such as the “Physics” which cost 3.00, which I cannot get until I receive money, and so am afraid I shall be behind in my classes. Please send me enough to pay the remainder of my fees before the twentieth for if I have to drop the course, all the amounts I have paid will be lost. It is very strange about your registered letter. If you will send me the number of your stub the P.O. here may be able to trace it. Please write to Mr. Rossiter about the money he let me have due to Mr. Danley’s4 signature on my application. His address is 30 Vesey St. I am taking dinner with a family I met in Cleveland until I can afford to eat here at school where board averages about seven a week. I hope to hear from you at once as I wish to pay back the money I have borrowed and buy my books and laboratory materials. In my next letter I will let you know about the school, and the exact amounts paid for fees, books, etc. Now I must go to class. Write me at 111 Hartley Hall, Columbia University.

Your son,

Langston Hughes

TO JAMES NATHANIEL HUGHES [ALS]

[On Hartley Hall, Columbia University, New York stationery]

October 27, 1921.

Dear Father:

Your letter of 13 inst. was received and I was certainly very glad to hear from you. The Post Office here has not yet received your registered letter as I have just inquired there, as well as at the Y. M. C. A. I think it must have gotten lost. It cannot be traced from this end as the P.O. here has no record of its arrival. I have not received the forwarded letter either but they do not matter. If you cannot trace the drafts and wish to send me the duplicates I will pay Mr. Rossiter and deposit the remainder with the school until I need it, as they keep funds for the students here.

Mrs. Danley was very kind about delivering the $250. She came over here to the University but could not find me, so left a note which I did not get until two days later as I was not expecting to receive letters at the school and had not called at the Office. However, I went to her home in Brooklyn where she had it for me.

The poem of mine in the June “Crisis” was copied in the “Literary Digest” of July 2 on their poetry page.5 I am unable to get an old number or would |have| sent it to you. It was also copied by the “Topeka Daily Capital.” I understand that some other newspapers published it, too, but I have not seen them. I just received today an invitation from Miss Fauset, Literary Editor of “The Crisis,” to take lunch with her next Tuesday.6

I am trying out for “The Spectator,” the daily newspaper published here at Columbia.7 The candidates receive 3 classes a week in newspaper work free.

I hope to hear from you soon.

Affectionately,

Langston Hughes

TO JAMES NATHANIEL HUGHES [ALS]

[On Hartley Hall, Columbia University, New York stationery]

February 14, 1922.

Dear Father:

I am sorry to tell you that the draft for $300 which you sent me on December 26 will not be sufficient to last me through the present term. I have now only enough money for my expenses until the end of March. Unless you are able to help me then, please send a letter to the Dean of the College asking that I be allowed to withdraw. I cannot do my best work here as long as I have to worry about my expenses, work after school, and stay up half the night washing my clothes. As this may be my last year in college I should like to get all that I can out of it and make a good record in case I should get a chance to return or to enter another school.

I did very well last term. According to my French instructor, my paper, which received an “A” mark, was the best one given to him in the final examinations. I received an “A-” on my term’s report. In Contemporary Civilization I also received an “A” on the three hour examination. It gave me a B+ on the report. As you will see when you receive it, my other marks were a “B” in English, a “B” in Physical Education, a “B-” in Oral French and a “C” in Phy. Ed A3 (Hygiene). I have been chosen this term as a member of a picked group of students (supposed to be the best) who are to do more advanced work in English than the other pupils, and are to receive the best instructors.

Have you read “Batouala?” You know the work of René Maran,8 the Negro, who received the Prix de Goncourt lately in France and is being so widely discussed. I have just borrowed a copy from Mr. Dill9 and find its French not hard to read.

I hope I shall be able to remain here until June.

Sincerely,

Your Son,

Langston.

TO JAMES NATHANIEL HUGHES [ALS]

March 2, 1922

Dear Father: I have your letter of Feb. 21. Enclosed you will find the itemized statement which you wish and also a letter which I received from the Dean showing that I have done good work here. The amounts which I received from you and which are not listed on the statement were used for food, laundry, and incidental expenses. I should need $150 to finish the term which ends June 14.

Please don’t think that I am trying to cheat you or am spending your money foolishly. If you think that, I had rather you give me nothing. Besides I never like to ask you for funds because I feel that you do not wish or cannot afford to give them, as I know you care very little about my going to college here and that you are not interested in what I want to study. You probably think that I am a bad investment and that you have more valuable things in which to put your money, so, as I stated in my letter of February 14, if you are unable to or do not desire to keep me here until the end of term, please send a request for my withdrawal to the Dean immediately and the amounts which I have paid for tuition for the rest of the semester will be reimbursed to you. That is fair, is it not? I don’t want to burden you if you can’t keep me in school. Besides, I cannot study and worry at the same time about every cent of money I must spend.—Your magazine subscriptions have been paid, the $2.25 was sent to the firm in Chicago, and your several letters of the dates to which you referred were received.

Sincerely Yours,

Langston

TO JAMES NATHANIEL HUGHES [ALS]

2289 Richmond Avenue,

Staten Island, New York,

June 22, 1922.

Dear Father:

I was very glad to get your letter and to hear that you are able to be about again.10 I still have the one hundred dollars you sent me last which I will return to you if you need it. If not I will keep it for my classes next fall which I want to take in extension. I did rather well in college but I don’t want to go back. My final grades were three “B’s” and a “C”. In trigonometry I failed. Columbia was interesting.11 Thanks for the year there. I am working on Staten Island for the summer but will be back in New York in the fall as I want to continue some of my classes in Columbia’s extension. Next spring I hope to go to France. I wish I could come to Mexico, if I could be of any help to you, but I don’t like Toluca. Take good care of yourself until you are well again and don’t overwork even then. Don’t send me anymore money. I have had enough; and do not worry about things—rest, get well.

Write to me soon. I hope you are regaining your health rapidly and that you will have completely recovered in a little while. Give my regards to the Fräu.12 Tell her I would write her but I am afraid she wouldn’t answer.

Affectionately, your son,

Langston.

TO JAMES NATHANIEL HUGHES [ALS]

2289 Richmond Avenue,

Staten Island, New York,

August 20, 1922.

Dear Father:

I have your letter of July 30th and was indeed glad to hear from you, but I am sorry to know that your arm does not seem to be improving with more rapidity. One must have patience though, I suppose.

Perhaps, by this time you have received the German paper which I sent you, but if not, its name, as nearly as I can spell it from memory is “Vossiche Zeitung.”13 The Fräu can probably tell you. It is a Berlin daily and my poem appeared as the conclusion to an article called “The American Negro” in the issue for Saturday, April 1st.

An interesting bit of news here at present is that Negro theatrical attractions are very much the vogue in New York now. After “Shuffle Along”14 closed a run of a year and two months (the record for a colored show), there have been four Negro companies playing in white theatres down town this summer, and one of them, after meeting with great success in a small house, has moved to the newest and, according to reports, the finest theatre in the city. “Shuffle Along” has gone to Boston for the summer. Then it will do Chicago, after which they have contracts for Europe. Its authors have signed to produce a play a year for the 63rd Street Theatre here for five years, besides doing numerous supper shows for the New York and Atlantic City cabarets. So the Negro theatrical world is booming. Bert Williams, did you read in the papers, left some $200,000 according to his will.15 Reports in Harlem say there is more, but it is being kept secret in order to avoid income tax.

James Nathaniel Hughes, c. 1930 (illustration credit 4)

Did I tell you that Miss Fauset has been reading my poems in the New York City high schools in her lectures on modern Negro poetry? They seem to take them seriously. Ha! Ha!

Please do not write me here after the third of next month as my month ends the tenth and I am returning to New York. What’s my job here?—You’d never guess—farming!!! Yes, a real 43 acre farm for me to exercise my talents on.16

Love,

Langston

S.S. West Hassayampa,17

Jones Point, N. Y.

February 6, 1923.

Dear Mr. Locke:18

I have had your delightful letter for a long while and I have wanted to answer you sooner, but so many things have intervened, a bad cold and a birthday,—I am twenty-one! And then I am a terrible correspondent. But I should like to know you and I hope you’ll write to me again.

It is too bad I am not living in New York anymore. I am missing so many interesting people. I am chasing dreams up here, though, and that’s an infinitely more delightful occupation even than being in New York, where all my old dreams had been realized; college, (horrible place, but I wanted to go), Broadway and the theatres—delightful memories, Riverside Drive in the mists, and Harlem. A whirling year in New York! Now I want to go to Europe. Stay for a while in France, then live with the gypsies in Spain (wild dream, isn’t it?) and see the bull-fights in Seville. My Spanish is good from having lived in Mexico and there’s no sport in the world as lovely as a “corrida de toros,” to those who like them.

Jeritza is wonderful, isn’t she?19 I fell in love with her last year and waited at the stage door for a smile and a rose. But have you seen Chaliapin in “Boris”?20 If you haven’t, please do. It’s the experience of a lifetime. And did you see the Moscow Art players?21 I couldn’t get in, so I comforted myself with seeing the “Chauve Souris”22 for the third time, and Jane Cowl’s Juliet.23 I suppose you saw Barrymore’s Hamlet,24 and maybe “Rain.”25 I have been telling all my friends to see it—“Rain”—but none of them take my advice. For me, it’s the finest thing, aside from “Hamlet,” I’ve seen this season, and stands out in my mind as “Anna Christie”26 from last year’s plays.

Countee27 told me about seeing the “World We Live In”28 with you. He has been doing some very beautiful poems lately, hasn’t he?

Jones Point is about forty miles up the Hudson from New York—a little white village almost pushed into the water by the snow-covered hills. And the Hassayampa is one of five “mother ships” anchored in the river in a forest of masts and cables belonging to a hundred other long old sea-going boats waiting for the Subsidy to pass, or something to happen to take them back to the sea. The sailors up here are the finest fellows I’ve ever met—fellows you can touch and know and be friends with. And after the atmosphere of college last year, being up here on the long ships is like fresh air and night stars after three hours in a dull movie show.

No I haven’t a single dramatic sketch.

I would be glad to hear from you again and to enjoy your friendship.

Sincerely,

Langston Hughes

Dear Mr. Locke:

I am writing this very hurried note because I want you to get it before you leave for New York. It would be inconvenient for you to come up to Jones Point and I can’t come down to the city just now, so I am afraid we will have to postpone our meeting until some other time. This is the most out of the way place and our ship is at the very end of the fleet, a good half mile of slippery gang-planks and icy decks from the shore landing. And then, at the end of your journey, you would find a very stupid person because I am always dumb in the presence of those whom I want to be friends with. You have written me such an understanding letter that I would like to know you, but I’d rather you wouldn’t come up here to see me.

I shall write you again soon.

Sincerely,

Langston Hughes

S.S. West Hassayampa,

Jones Point, New York,

February nineteenth, 1923.

Dear Countee:

Certainly it is very kind of you to offer to read my poems for me at the library and very beastly of me not to have written a single line since returning from New York. I’m an absolutely shameless person, am I not? But, anyway, I hope you liked some of the poems I sent you but if you didn’t, and would like to, you may read some of my old things,—“The Negro” or “The Negro Speaks of Rivers,” or the group of poems from last March’s “Crisis,” or any of the published stuff that you choose. Miss Fauset can send them to you. “Our Land” and “Dreams,” though, are going to be used in “The World Tomorrow” so perhaps you’d better not read them. “Joy” and “Tragedy” were sent out a month ago to “The Bookman”29 but I’ve heard not a word about them, nor have they been returned, you may use them, if you like. But please don’t read “Fascination.” But does that leave you enough to choose from? I wrote Miss Rose, in answer to her letter, that I had sent my material to you, and that you had very kindly offered to read for me.30 You know, I wouldn’t dream of reading anything, if I were there.

What’s happened to “Kelley’s”31 and have you or I had anything in “The Crisis” recently?

Thanks a lot for your “To a Brown Boy.” I don’t know what to say about the “For L.H.” but I appreciate it, and I like the poem. I’m glad it was accepted.

Ridgely Torrence wrote me asking if I would send something for a special Negro number of “The World Tomorrow”.32 They returned my “Three Poems of Harlem,” but kept “Dreams,” “Our Land” and another that I don’t believe you have,—“Poem for the Portrait of an African Boy after the Manner of Gauguin.” (Terribly long title, isn’t it?) I was surprised at their keeping them as I was afraid they weren’t quite the thing that they’d want.

I’ve had another delightful letter from Mr. Locke. Did you see him in New York over the holiday week-end? He wrote me that he would be there and that he wanted to come up here, which frightened me stiff. He writes such charming letters that I would be afraid to meet him because I know he’d find me terribly stupid.

Have you seen the Moscow Art Theatre yet? I see they’re staying for an extra four weeks.

I haven’t written Donald.33 I have had so very much to do. We are moving from one ship to another. And it takes me hours to write a decent letter. Then, too, I’ve been working on my poems, copying manuscripts and getting them together as I may be moving soon. You know, spring’s coming and I feel the call of the road, or shall it be the sea this time. Do you know that poem of Edna St. Vincent Millay’s, “Travel,” I believe it’s called, that closes:

“My heart is warm with the

friends I make

And better friends I’ll not be

knowing

Yet there isn’t a train I

wouldn’t take

No matter where it’s going.”

Don’t you ever get that feeling sometimes? To go somewhere, anywhere, just to be going. I suppose that’s one of the reasons why I couldn’t stay in college. I spent more time last spring on South Street looking at the ships than I did in the Dorms.

Say, there’s a most beautiful Pierrot cover on La Vie Parisienne34 for February third. If you’re ever down on Sixth Avenue some time stop in one of the little French bookshops and see it. The copy we have up here is the Swede’s or I’d send it down to you.

Write me soon.

Sincerely,

Langston

Box 37

Jones Point, N.Y.

March 4, 1923.

TO COUNTEE CULLEN [ALS]

Dear Countee:

I am sorry, but I have not another thing that you can read unless you want to be divertingly original and give them this:

SYLLABIC POEM

Ah ya!

Ah ya!

Ky ya na mina.

So lee,

So lee nakyna.

Ky ya na mina,

Ky ya na mina.

Tell them that it is the poetry of sound, pure sound, and that it marks the beginning of a new era, an era of revolt against the trite and outworn language of the understandable. Wouldn’t that be amusing? Then they could discuss the old question as to whether artists and poets are ever sane. I doubt if we are. But, seriously, I haven’t anything else decent to send you. Read my old things, if that would help you any.

Tell me about the programme.35 Who’s on and who’s coming?

If you wanted me to come, I’m sorry that I won’t be able to. But I may perhaps be in New York anyway soon. The Subsidy failed to pass so our fleet may be left alone to rust.36

Your friend,

Langston

Box thirty-seven,

Jones Point, New York,

March seventh, 1923.

Box Thirty Seven

Jones Point

April Sixth, 1923

Dear Friend,

I am sorry I have been so long in writing you but it seems that letters are always my hardest tasks—not the actual writing of them, but the getting ready to write them. And the time slips by so rapidly! But I did enjoy your last letter a great deal and I believe that you are a Sympathetic friend. So many friends aren’t. They are only well meaning.

I can quite understand why you like the Germans. I like them, too,—those whom I have known. I met a number of them in Mexico (our housekeeper happened to be a German lady and they were delightful people).

Do you teach Greek or the classics? I have read nothing but the Odyssey and a few of the tragedies but love them. They were the only things college gave me, (other than a supreme dislike for college). But I am glad that I’ve known Telemachus and the beauty of Homer’s wine dark sea. The Odyssey is truly a marvelous thing!

Up here I have been reading Nietzsche and Conrad, Walt Whitman and Pio Baroja.37 Down in New York I saw “Will Shakespeare,” Jane Cowl’s “Romeo and Juliet,” Nazimova’s “Salome”38 and the Moscow Art Players do “The Lower Depths”.39 Did you ever see Duse40 in Europe? I want to. And did you ever see Mimi Aguglia? She and Grasso41 gave some very fine performances at the Irving Place Theatre last winter. I saw them do Benavente’s “Malquerida.” I didn’t get to hear a single opera this winter, and I wanted to, especially those of the “Ring”.42 But I did both hear and see “Liza” and it’s a perfect diamond of joy!43 Didn’t you think so?

Tell me sometime about the Howard Players and your work with them.

Do you know a young fellow at Howard by the name of Moon (Edward, I believe) from Cleveland?44 We both graduated there in the same year. And do you know Jean Toomer?45 I have liked some of his work very much in “The Liberator” and “The Crisis.”46

An Easter card from Countee |Cullen| in Washington told me that he was having a delightful time. You must be a charming friend for poets. And you say that we are reaching the poet’s dangerous age. I don’t know, but anyway I do want your help, and friendship, and criticisms. And how good you are to offer them to me! So I am sending you an envelope of poems to read. I am afraid that none of them are particularly good, but if you should like any of them well enough to send out for me, I would be very glad. I had thought of Poetry and the Little Review, but then I was afraid |they weren’t| good enough for one nor eccentric enough for the other.

I shall perhaps be here only a month or so more, until the spring comes over the high hills and down to the river’s edge. There are fruit trees all along the west bank waiting for flowers. I’ve had a glorious winter. I’ve made strange friends for whom I care a great deal and met many poets, although they never write their poems, and potential artists, who do not develop their talents (but I have persuaded one to take a correspondence course and another to try to enter an art school when he goes to New York). And there have been nights of sailor’s chanties and songs in Swedish and German, Italian and Spanish, and games, and stories of days on sailing ships, and trips around the Horn, and nights in Bombay and Cape Town. Do you wonder that of my four volumes, Nietzsche and Conrad, Walt Whitman and Pio Baroja, I have finished and well read but one? Of course, I’m stupid and only a young kid fascinated by his first glimpse of life, but then after so many years in a book-world and so much striving to be a “bright boy” and an “intelligent young man” it’s rather nice to come here and be simple and stupid and to touch a life that is at least a living thing with no touch of books.

But I am boring you, no? Anyway, I hope you’ll write me soon.

Sincerely,

Langston Hughes

Dear Countee:

I was very glad to receive both your letter and your card from Washington, where you must have had a delightful time. Tell me about it. You visited Howard, of course. How is it? What else did you do? Is Mr. Locke married? I have just written to him and mailed off an envelope of poems.

Thanks so much for your criticisms. I’ll bet Donald |Duff| was the friend who checked the poems, wasn’t he? For who else could have liked just those things? So the Poetry Evening came off nicely? Who all were there? Mr. |Augustus Granville| Dill must have been as he writes me that he’s heard of my being in town numbers of times and not even calling him up. He says that Hall Johnson, the violinist, has written for permission to do a musical setting for my “Mother to Son” and wonders what my “reaction to that will be.”47 Have you seen Miss Fauset lately?

At last, I’ve heard from Kelley’s. He’s keeping my stuff for the Amsterdam News. But not a word from The Bookman yet. Isn’t that a scream of a poem over my “Black Pierrot”? I’d rather have written it.

Seen any new plays lately? I haven’t done a thing intellectual since returning from New York, except to write a few verses, and attempt to discover (to my financial embarrassment) the secret of luck in poker. Now I shall be here until sometime in May.

I am sending you an envelope of things—Miss Fauset’s article on color from last year’s Negro Number of the “World Tomorrow,” an article on your beloved Housman from the Lib,48 a Sailor’s Song that I rather like, and a song from Andalusia that I translated myself. And two poems of my own in rhyme. How’s the “chansons vulgaires” for vulgar songs? Is it good French? I have another beauty of a cabaret poem that came to me in New York <unfranc ish>. Do you ever visit any of those little cellar places? They’re interesting and very Harlemish.

Write to me soon. Where’s the poem you were going to send?

Sincerely,

Langston

Box thirty seven,

Jones Point, N.Y.

April seventh, 1923.

|c. May 1923|

Dear Mr. Locke:

I was very glad indeed to receive your letter and interested by what you told me about my poetry, and about your summer plans,—Knickers and sandals on the German roads, then Egypt, the tombs and the pyramids. How wonderful! I wish I were going with you.

I have read a little about the German Youth Movement and I remember seeing a motion picture showing a band of young folk tramping to an old baronial castle for a holiday. By the way, did you read about Countee |Cullen|’s speech to the League of Youth in New York?

You are right that we have enough talent now to begin a movement. I wish we had some gathering place of our artists,—some little Greenwich Village of our own. But would our artists have the pose of so many of the Villagers? I hate pose or pretension of any sort. And especially sham intellectuality. I prefer simple, stupid people to half-wise pretenders. (But perhaps it’s because I’m stupid myself and half ashamed of my stupidity. I don’t know. I never studied psychology. I wish that I had.)

I am going to have some pictures taken this week, (one for Mr. Kerlin’s “Negro Poets”)49 and I shall send one to you. Then if we meet on some strange road this summer we shall recognize one another. I think that I should know you although I have never seen you. Perhaps it’s because I do know you and like you that makes me feel as though I have already seen you.

Have you ever been to Spain? It must be a gorgeous land. I’ve always dreamed of going there.

Have you ever read D’Annunzio’s “The Flame of Life”?50 It is pagan and very lovely, filled with the beauty of Venice in autumn, and half-dead myths.

Do you like Walt Whitman’s poetry? His “Song of the Open Road” and the poems in “Calamus”?51 I do, very much. And have you read, or tried to read, Joyce’s much discussed “Ulysses”?

I shall see the Chicago Players in “Salome” when I go down for the pictures. Thanks for telling me about them as I hadn’t heard before.

Write to me again soon.

Sincerely,

Langston Hughes

Jones Point, New York,

Thursday

TO ALAIN LOCKE [ALS]

|c. May 1923|

Dear friend,

Your charming and generous letter has been on my table for the last two weeks and I have not been able to bring myself to answer it,—disappointingly, at least for me. But I can’t go with you this summer. My “I wish I could go with you” did really mean so, but for more than one reason, I must work the entire summer. Even at that, though, I may get to Europe or northern Africa as I hope to work on a freighter going to the Mediterranean. Perhaps, some fine day, we may even meet in Piraeus or Alexandria. I shall try to let you know what ports I touch. And how delightful it would be to come surprisingly upon one another in some Old World street! Delightful and too romantic! But, maybe,—who knows?

Anyway, I am sending you the promised picture. It does look something like me. I am not autographing it for you, but I will, if you wish it, when I come to Howard, as I hope to, for a visit at least, if not to continue my suddenly and gladly (though sadly) interrupted education.

Please write to me soon as I shall not be here much longer. The hills are at their loveliest now and I do not like to go, but then there are other rivers in the world to see besides the Hudson. And Oh! so many dreams to chase!

Your friend,

Langston Hughes

Jones Point, New York,

Friday

1 In 1903, James Nathaniel Hughes (1871–1934) began work at the American-owned Pullman Company in Mexico City. Fired without explanation in 1907, he moved to Toluca in 1909 to work for the American-owned Sultepec Electric Light and Power Company. Eventually, he owned property in Mexico City, a house in Toluca, and a ranch in the mountains nearby.

2 His father, who wanted Langston to become an engineer and settle in Mexico, agreed to fund one year of study at Columbia, with the prospect of further support if he did well as a student. Father and son got along poorly. Writing about the summer of 1919, which he had spent with his father in Toluca, Hughes later declared in The Big Sea that it was “the most miserable I have ever known. I did not hear from my mother for several weeks. I did not like my father. And I did not know what to do about either of them.”

3 C. L. Rossiter was a New York–based executive of the Sultepec Electric Light and Power Company.

4 R. J. M. Danley, another official of the Sultepec Electric Light and Power Company, was an American colleague of James Hughes in Mexico. He and his wife also made a personal loan to Hughes of $250 (see letter dated October 27, 1921).

5 Founded in 1910 by W. E. B. Du Bois (1868–1963), The Crisis is the monthly magazine of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). This appearance marked Hughes’s first publication in a national magazine with an adult readership (in January, his poems “Fairies” and “Winter Sweetness” had appeared in The Brownies’ Book, a magazine for black children, with ties to The Crisis). The poem was reprinted later that year in The Literary Digest, which had a mainly white readership.

6 Jessie Redmon Fauset (1882–1961) was the literary editor of The Crisis from 1919 to 1926, and the author of There Is Confusion (1924) and three other novels. Hughes wrote in The Big Sea that Fauset, along with Charles S. Johnson and Alain Locke, had “midwifed the so-called New Negro literature into being. Kind and critical—but not too critical for the young—they nursed us along until our books were born.”

7 The student-run Columbia University Spectator published four poems by Hughes using the pseudonym “LANGHU” or “LANG-HU.” However, as Hughes wrote in The Big Sea, “when I tried out for the Spectator, they assigned me to gather frat house and society news, an assignment impossible for a colored boy to fill, as they knew.”

8 When the French writer René Maran (1887–1960) received the Prix Goncourt in 1921 for his novel Batouala, he became the first person of African descent to win it. Since 1903, the Prix Goncourt has been awarded annually for the best new book of prose written in French. Hughes would meet Maran in Paris in 1924 (see letter dated July 4, 1924).

9 Augustus Granville Dill (1881–1956) was the Harvard-educated business manager of The Crisis until 1928, when his mentor W. E. B. Du Bois summarily fired him after his arrest by the police for alleged homosexual activities. In The Big Sea, Hughes loyally described Dill as “a short, voluble man of middle-age who, besides running the magazine, was a fine musician on the pipe organ and the piano forte (as he always said) as well. He attended the Community Church, where John Haynes Holmes preached, and sometimes played the organ for services there. He told them of my poetry, and that church was, I believe, the first church in which I was invited to read my poems.”

10 In May, James Hughes suffered a severe stroke. Although he made a substantial recovery, his right arm remained paralyzed.

11 In The Big Sea, Hughes wrote: “I had no intention of going further at Columbia.… I felt that I would never turn out to be what my father expected me to be in return for the amount he invested. So I wrote him and told him I was going to quit college and go to work on my own, and that he needn’t send me any more money. He didn’t. He didn’t even write back.”

12 Bertha Schultz was James Hughes’s housekeeper. She became his wife in January 1924.

13 A German liberal newspaper published from 1911 to 1934.

14 The landmark musical Shuffle Along, which opened in 1921, helped to launch the Harlem Renaissance. It was written by Flournoy Miller and Aubrey Lyles, with music and lyrics by Noble Sissle (like Hughes, a graduate of Central High in Cleveland) and Eubie Blake. The four men comprised the first African American team to develop a successful Broadway show.

15 Bert Williams (1874–1922) was one of America’s greatest vaudeville stars. After the death of his partner, George Walker (c. 1873–1911), who had been a childhood friend of Hughes’s mother in Lawrence, Kansas, Williams pursued a successful solo career. He joined the Ziegfeld Follies as its only black performer and became its highest-paid star.

16 Despite his year at Columbia, the color line barred Hughes from many jobs before he was hired to work on a vegetable farm on Staten Island belonging to two Greek brothers and their wives. In The Big Sea, he wrote that they “didn’t care what nationality you were just so you got up at five in the morning and worked all day until it was too dark to see the rows in the field.” Despite the long hours, he found this job deeply satisfying.

17 In mid-October of the previous year, Hughes had started to work as a mess boy at Jones Point. The U.S. Shipping Board mothballed a large fleet of vessels there (109 during Hughes’s tenure) after World War I. Hughes served aboard the Oronoke, the Bellbuckle, and the West Hassayampa.

18 With degrees from Harvard and some years at Oxford, where he had been a Rhodes scholar, Dr. Alain Locke (1886–1954) was the chair of the Department of Philosophy at Howard University in Washington, D.C., from 1921 until his retirement in 1953. His books include The New Negro (1925), The Negro in Art (1941), and (with Bernard J. Stern) When Peoples Meet: A Study in Race and Culture Contacts (1942). Sent Hughes’s address by Countee Cullen, Locke wrote in February to tell him that each of Hughes’s friends “insists on my knowing you. Some instinct, roused not so much by the reading of your verse as from a mental picture of your state of mind, reinforces their insistence.”

19 The Austrian American soprano Maria Jeritza (1887–1982), who sang the part of Marietta in the first Vienna performance of Erich Wolfgang Korngold’s Die tote Stadt in 1920, reprised the role at her Metropolitan debut in 1921.

20 The Russian operatic bass singing star Feodor Chaliapin (1873–1938) performed the title role of Modest Mussorgsky’s Boris Godunov at the Metropolitan Opera House in 1921.

21 The Moscow Art Theatre was founded in 1898 by Constantin Stanislavsky and Vladimir Nemirovich-Danchenko. Their innovative approach to theatrical production helped to create modern theater. The Moscow Art Theatre began its American tour with an eight-week engagement in New York City that opened at Jolson’s 59th Street Theatre on January 8, 1923.

22 The Chauve-Souris, or the Bat Theatre of Moscow, was a theater group led by Nikita Balieff (1876?–1936), a vaudevillian and former member of the Moscow Art Theatre. On February 3, 1922, Balieff and his troupe began an engagement lasting seventeen months in New York City. The Chauve-Souris gave its four hundredth performance on January 4, 1923, in honor of the recent arrival of the Moscow Art Theatre company in America.

23 A playwright and actress, Jane Cowl (1883?–1950) appeared as Juliet in Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet at Henry Miller’s Theatre on 43rd Street in Manhattan in 1923.

24 John Barrymore (1882–1942) performed the title role of Shakespeare’s Hamlet at the Sam H. Harris Theatre on Broadway from November 1922 to February 1923.

25 Rain: A Play in Three Acts (1923) is John Colton’s adaptation of W. Somerset Maugham’s short story “Miss Thompson,” later called “Rain” (1921).

26 Anna Christie won Eugene O’Neill the Pulitzer Prize for Drama in 1922.

27 Countee Cullen (1903–1947), Hughes’s close friend and literary rival, was a major poet of the Harlem Renaissance. Unlike Hughes, he preferred traditional forms, such as the villanelle and sonnet, and found his main inspiration in the European classics. He won several literary prizes for poems that appeared in periodicals such as Opportunity, The Crisis, Harper’s, and The American Mercury. In 1925, Harper & Brothers published his first volume of poetry, Color.

28 The World We Live In, also known as The Insect Comedy or The Insects, was written by the Czech brothers Josef and Karel Capek. It ran on Broadway at Jolson’s 59th Street Theatre from October 1922 to February 1923.

29 The Bookman, a prominent American review published from 1895 to 1933, accepted neither “Joy” nor “Tragedy.” “Joy” first appeared in The Crisis in February 1926. “Tragedy” (its first lines are “Pierrot / Took his heart / And hung it / On a wayside wall”) was retitled “Heart” and first appeared in One-Way Ticket (1949).

30 Ernestine Rose (1880–1961), a white librarian and social activist, organized popular evenings of poetry readings, lectures, and social events at the 135th Street Branch Library in Harlem.

31 William M. Kelley (1894–1958) was the editor of the Harlem-based New York Amsterdam News. The paper published the poems “A Black Pierrot” and “Justice” in its April 4 and April 24, 1923, issues.

32 Ridgely Torrence (1874–1950), a white poet, dramatist (the landmark Three Plays for a Negro Theater, 1917), and editor of The New Republic from 1920 to 1924, prepared a special number on blacks for the magazine The World Tomorrow (May 1923). He chose three poems by Hughes (“Dreams,” “Our Land,” and “Poem: For the portrait of an African boy after the manner of Gauguin”). This marks the first time Hughes’s work (apart from reprintings) appeared in a journal circulated mainly to a white audience.

33 Probably Donald Duff, a close friend of Countee Cullen and Harold Jackman, with ties to the leftist magazine The Liberator. Cullen dedicated his poem “Tableau” to Duff.

34 La Vie Parisienne was an erotic French magazine.

35 Cullen read some of Hughes’s poems as well as some of his own at a poetry reading at the 135th Street Branch Library.

36 Hughes asserts in The Big Sea that he left because “I thought it was about time to leave the dead ships and find a vessel that was moving. So I quit the fleet and went back to New York, determined now to get on a boat actually going somewhere.”

37 Pío Baroja (1872–1956) was a Spanish author whose trilogy of novels, La Lucha por la Vida (“The Struggle for Life”), published between 1922 and 1924, depicts the world of the Madrid slums.

38 The world-famous Russian-born actress Alla Nazimova (1879–1945) partially financed, produced, and starred in Salomé, a silent screen adaptation of Oscar Wilde’s play of the same name. The film was released in February 1923.

39 The Lower Depths, first produced by the Moscow Art Theatre in 1902, is perhaps the best-known play by the Russian writer Maxim Gorky (1868–1936).

40 Eleanora Duse (1858–1924) was a renowned Italian actress. At Jones Point, Hughes had read Gabriele D’Annunzio’s novel The Flame of Life (1900), in which he drew on his intimate friendship with Duse. Later that year, when Hughes attended the premiere of Duse in Ibsen’s La Donna del Mare at the Metropolitan Opera House, he was disappointed: “She seemed just a tiny little old woman, on an enormous stage, speaking in a foreign language, before an audience that didn’t understand.”

41 Mimi Aguglia (1884–1970) and Giovanni Grasso (1873–1930) were Italian actors and two of the founders of the Sicilian Theatrical Company.

42 Richard Wagner’s four epic operas The Ring of the Nibelungen (1853) are often called The Ring Cycle.

43 Liza, an all-black musical comedy, introduced the dance sensation called the Charleston to New York during its run on Broadway from November 1922 to April 1923.

44 Probably Henry Lee Moon (1901–1985), a friend from his teenage years in Cleveland who later worked as a prominent journalist for the New York Amsterdam News and as editor of The Crisis. Moon also accompanied Hughes and twenty other young African Americans on a visit to the Soviet Union in 1932 to work on a film (soon abandoned) about American race relations.

45 Jean Toomer (1894–1967) was an influential African American poet and fiction writer. Published that year (1923), his book Cane is a collection of poems and stories about black life in Washington, D.C., and in the rural South. The sections of Cane that appeared in The Liberator are “Georgia Dusk” (September 1922), “Carma” (September 1922), and “Becky” (October 1922). “The Song of the Son” appeared in The Crisis (June 1922).

46 The Liberator was the successor to the Greenwich Village left-wing magazine The Masses.

47 Hall Johnson (1888–1970), an African American choral director, composer, and violinist, set Hughes’s poem “Mother to Son” to music. Passionate about preserving the spirituals, he founded the renowned Hall Johnson Choir in 1925.

48 A. E. (Alfred Edward) Housman (1859–1936) was an acclaimed British classics scholar and poet. His collection of lyrical verse A Shropshire Lad (1896) brought him international fame. Floyd Dell’s article “Private Classics,” which appeared in the January 1923 issue of The Liberator, discusses Housman’s volume Last Poems (1922).

49 Robert T. Kerlin (1866–1950), a controversial white professor of English and History, edited the landmark anthology Negro Poets and Their Poems (1923), which includes Hughes’s poem “Negro.” In 1921, the Virginia Military Institute fired him because of his various publications on behalf of black rights.

50 Gabriele D’Annunzio (1863–1938), an Italian poet and playwright, was the author of the novel The Flame of Life (1900). See also letter of April 6, 1923, fourth footnote.

51 Whitman’s group of poems called “Calamus,” introduced in the 1860 edition of Leaves of Grass, is often noted for its homoeroticism.