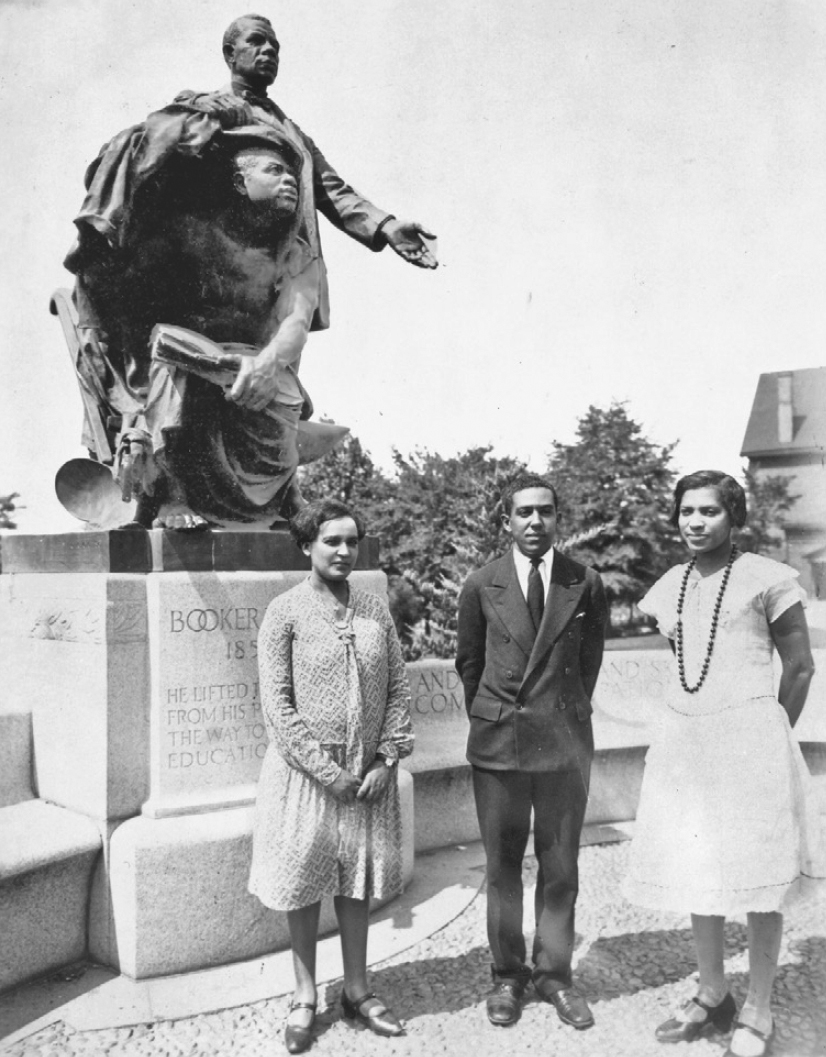

With Jessie Fauset and Zora Neale Hurston at the statue of Booker T. Washington, Tuskegee Institute, 1927

With Jessie Fauset and Zora Neale Hurston at the statue of Booker T. Washington, Tuskegee Institute, 1927

And the tom-toms beat,

And the tom-toms beat,

And the low beating of the tom-toms

Stirs your blood.

In 1923, Hughes secured a job as a mess boy on the West Hesseltine, a freighter bound for Africa. On June 13, as the ship put out to sea, he decided to throw all of his books overboard. He recalls the moment in The Big Sea: “It was like throwing a million bricks out of my heart—for it wasn’t only the books that I wanted to throw away, but everything unpleasant and miserable out of my past: the memory of my father, the poverty and uncertainties of my mother’s life, the stupidities of color-prejudice, black in a white world, the fear of not finding a job, the bewilderment of no one to talk to about things that trouble you, the feeling of always being controlled by others—by parents, by employers, by some outer necessity not your own. All those things I wanted to throw away.” In an earlier draft of The Big Sea, however, Hughes wrote that he saved one book, his copy of Whitman’s Leaves of Grass: “I had no intention of throwing that one away.”

On another voyage the following year, he crossed the North Atlantic to Rotterdam, where he jumped ship and headed to Paris. There he found a job washing dishes in a jazz club in Montmartre. These two adventures seemed to inspire him as a poet. After a month-long stay in Italy, he was about to return to the United States when thieves stole his money and passport. As a result, he was stranded in Genoa for more than a month. This ordeal moved him to write one of his best-known poems, “I, Too.”

Lagos, Nigeria,

July 21, 1923,

S/S West Hesseltine.1

Dearest Mother:2

We are at Lagos, British Nigeria, now, just eight ports from the end of our trip.3 This is the first town since Dakar at which we have had shore leave or a chance to mail letters.

I’m having a delightful trip and, you won’t believe it, but it’s cool over here, really cool. This is the rainy season and the weather is fine, and at sea always a continuous breeze.

We’ve about a hundred and fifty on board now,—our regular crew and passengers, and a gang of African helpers—Kru boys. I have two, both about the age of Gwyn4—but wonderful little workers—and smart! Their father is a head-man. The kids aren’t paid, but the men get two shillings a day, and each and every human consumes about ten pounds each of rice a meal!

Our one colored passenger is getting off here. He is a tailor and enthusiastic about business prospects in Africa. He is going to open a shop here and a school. The white missionaries are going clear down to the Congo, about two weeks yet. There we are going to load mahogany logs and palm oil and start back. I’m going to get the monk there, too.5 There are two on board already doing all sorts of pranks. I’ll write you again soon. Hope you got all my letters. Lots of love to you. One kiss.

Langston

S. S. Hesseltine,

Lagos, Nigeria,

July 21, 1923

Dear Countee:

This is our sixteenth port, Lagos, just where the coast curves south again. From here we go to Duala, and then ninety miles up the Congo to Boma and Matadi. We’ve had no shore leave since Dakar so about the most I’ve seen of Africa has been the orange-yellow sands of the coast and the roofs of white houses hidden in groves of cocoanut trees. We usually anchor out and our cargo is taken by surf boats in charge of eight oars-men whose paddles are three-pointed like Father Neptune’s fork and the oars-men themselves gorgeously naked save for a whisp of loin-cloth.

We have about sixty Kru boys from Freetown on board now as workers, so everyone has a helper. I have two kids who work excellently well, but who eat better. They each consume a dish pan full of rice at every meal, chewing untiringly, and then are not full.

Our own ship’s crew is a mixed lot. The engine room gang, from the chief down, are Irish, the sailors mostly of the “white-headed race” with a Porto Rican and a few Americans mixed in. The “old man” himself is a Dutchman whose breeches are a yard wide and his pipe almost as long. And the steward and the galley men Phillipinos. And we four, the mess-boys—one from San Juan, one from Kentucky, one from Manila, and I—where am I from?

I’ll write again at Matadi.

Sincerely,

Langston

TO COUNTEE CULLEN [ALS]

Freetown, Sierra Leone,

October 1, 1923,

S/S West Hesseltine.

Dear Countee:

We are homeward bound. Only one more port and then across to Manhattan—and Harlem. We are a month late now but then we have almost a full cargo—palm oil, cocoa beans, and mahogany logs, and here we load ginger and pepper. And then we’ve been everywhere—up rivers, branch rivers and creeks, surf ports and harbor ports, and visited about every colony on the West Coast. We have had delightful weather all the whole summer, too, but now the hot season is beginning, so I am glad we are getting away. I have had a very interesting trip, though, and have seen more of Africa than I ever expected to see. And tonight the sunset! Gleaming copper and gold and then the tropical soft green after-glow of twilight, and now stars in the water and luminous phosphorescent foam on the little waves about the ship and ahead the light of Freetown toward which we are steering through the soft darkness.

I’ll be up to see you soon after this letter. I am anxious to be back again. Just a little bit homesick for New York.

Sincerely,

Langston

Be in about November first.6

|February 4, 1924|

Dear Friend:

Forgive me for the sudden and unexpected message I sent you.7 I’m sorry. I should have known that one couldn’t begin in the middle of the term and that I wasn’t ready to come anyway. But I had been reading all your letters that day and a sudden desire came over me to come to you then, right then, to stay with you and know you. I need to know you. But I am so stupid sometimes.

However I am coming to Howard and I want to see you and talk to you about it.

I am sailing again tomorrow but you may write me in Holland—

S/S McKeesport,

c/o Agent, Cosmopolitan Line,

Rotterdam, Holland.8

I was so pleased to get your card from Cairo.

Sincerely,

Langston

Dear Countee:

I am in Paris. I had a disagreement on the ship, left, and came to Paris purely on my nerve, as I knew no one here and I had less than nine dollars in my pocket when I arrived.9 For a week I came as near starvation as I ever want to be, but I got to know Paris, as I tramped from one end to the other looking for a job. And at last I found one and then another one, and yet another!

Happily or not, I have fallen in to the very whirling heart of Parisian night life—Montmartre, where topsy-turvy, no one gets up before seven or eight in the evening, breakfast at nine, and nothing starts before midnight. Montmartre of the Moulin Rouge, Le Rat Mort, and the famous night clubs and cabarets!

I myself go to work at eleven pm and finish at nine in the morning. I’m working at the “Grand Duc” where the culinary staff and the entertainers are American Negroes. One of the owners is colored, too. The jazz-band starts playing at one and we’re still serving champagne long after day-light. This is my second cabaret job within the last two weeks. I’m vastly amused. But at my first place glasses and even bottles were hurled too often for me. The “Grand Duc” is not so wild and then our folk are quite chic. Last night we had a prince in the house and his party.

But about France! Kid, stay in Harlem! The French are the most franc-loving, sou-clutching, hard-faced, hard-worked, cold and half-starved set of people I’ve ever seen in life. Heat—unknown. Hot water—what is it? You even pay for a smile here. Nothing, absolutely nothing is given away. You even pay for water in a restaurant or the use of the toilette. And do they like Americans of any color? They do not!!! Paris—old and ugly and dirty. Style, class? You see more well dressed people in a New York subway station in five seconds than I’ve seen in all my three weeks in Paris. Little old New York for me! But the colored people here are fine, there are lots of us. I’ll tell you in my next letter. Please write me now. I did not get your Rotterdam letter.

Sincerely,

Langston Hughes

Address:

15 Rue Nollet,

Paris XVIIe, France.

Hughes doodled this streetlamp in the margin of his letter to Cullen. (illustration credit 16)

Be sure to use the XVIIe or else I doubt if anybody in the world could find this street.

I’ve just had tea over in the Latin Quarter with three of the most charming English colored girls!10—Claude McKay11 just left here for the South—Smith12 is in Brussels—Roland Hayes13 is coming.

TO ALAIN LOCKE [ALS]

15 Rue Nollet,

Paris (XVIIe) France,

April 23, 1924

Dear Mr. Locke:

It’s two months today since I came to Paris and I am just now beginning to like the city a little. Perhaps because it’s the fourth day of sunshine in the whole two months, and Parisian houses are so cold! But the gardens were lovely Sunday and the young leaves are coming out on the trees along the boulevards. Never, though, until this week, had I missed the sun so much before. And French people! (Mon dieu!!) I can’t ever love them. Yesterday I heard Raquel Meller14 sing and the old desire of seeking the sun in Spain came over me. But I think I’d better stay here for a while. Paris is still amusing. And then I have a “jazzy” job in a Montmartre cabaret where one gets a sort of back stage view of “the gay life,”—the other side of the smile, so to speak.15 It’s interesting.

Please tell me, how’s chances for me at Howard? I should like very much to come there next September. (If I save my fare. If not I shall go on to Spain.) If I come, I shall have to depend entirely on myself for all expenses. I can do almost all sorts of work now and perhaps tutor Spanish or French. Please, dear friend, let me know about this. I do want to come.

Are you coming over this summer|?| If so, of course I will see you. I hope so.

Write to me,

Sincerely,

Langston

Paris, France,

15 Rue Nollet (XVIIe)

May 25, 1924.

Dear Harold:16

Stay home! Europe is the last place in the world to come looking for a job, and unless you’ve got at least a dollar for every day you expect to stay here, don’t come! Jobs in Paris are like needles in hay-stacks, for everybody, and especially for English-speaking foreigners. The city is over-run with Spaniards and Italians who work for nothing, literally nothing. And all French wages are low enough anyway. I’ve never in my life seen so many English and Americans, colored and white, male and female, broke and without a place to sleep as I have seen here. Yet if you’d give them all a ticket home tomorrow, I doubt if ten would leave Paris. Not even hunger drives them away. The colored jazz bands and performers are about the only ones doing really well here. The rest of us, with a dozen or so exceptions, merely “get along.” The others, in “hard luck” beg, borrow, gamble, or steal for a living until something better turns up. And to be broke in Paris is a “pain.” Then a franc (six cents) over here is harder to get than a dollar in New York.

The French colored people, and there are many, seemingly live and work under about the same conditions as other Frenchmen. But those conditions are bad enough. Personally, I think I had rather be a colored worker in New York than a colored or white worker over here, as far as wages, hours, and conditions are concerned.

About mademoiselles—one will live with you forever if you only pay the room rent.17 Girls’ wages are so low here that they can’t afford to live alone. And in Montmartre, at least, nobody ever takes the trouble to get married.

If I were you, tho, I wouldn’t come over, unless you’ve got the dollars to back you up. As far as—working on boats goes,—it’s a tough life, kid. Neither you nor Countée |Cullen| is enough of a “bum” to enjoy it. And getting a boat is not so easy unless you’ve had experience. You see I did six months on the laid-up fleets before I went to sea.

I am sorry if I am discouraging you with all my would-be good advice. But if you’re like me you’ll do as you want to do, anyhow. I always do as I want, preferring to kill myself in my own way rather than die of boredom trying to live according to somebody else’s “good advice.” Besides, adventure is two-thirds uncertainty. Had I been sure about Paris, I wouldn’t have been nearly as thrilled as I was when I came here with eight dollars, and wondered how Fortune would let me live. But then I’m a “nut.” You needn’t be one. It’s better to stay home.

Sincerely,

Langston

Paris, France,

15 Rue Nollet,

June 27, 1924

Dear Countee:

Thanks for your letter. I certainly do like to hear from you. Your letters are a breath of home. But your Suicide Chant doesn’t excite me. The me and the seed, and the weed and the deed don’t quite hang together.18 If it were not for the title I wouldn’t know what it’s all about. Really, I think it is the worst thing you’ve ever done. Most of your poems are beautiful but this one isn’t. The fourth verse is nice, but the rest—Oh, mon Dieu!.… Excuse me! As to my own poem,—people are taking it all wrong.19 It’s purely personal, not racial. If I choose to kill myself, I’m not asking anybody else to die, or to mourn either. Least of all the whole Negro race. But it’s all right, the Pittsburgh Courier’s giving me a bit of free advertising anyway, aren’t they?

And have you also heard from the Boston gentleman who is also issuing a book on Negro poetry—a Dictionary |or| Negro Anthology he says?20 We’ll have plenty of books, won’t we?

I’m very anxious to see Mr. Locke, tho I came near leaving Paris yesterday,—had a sudden notion that I wanted to see the sea again. But I am going to try to stay until he comes, besides I’ve got a wonderful idea for a story that I want to work out with the night life of Montmartre as a background and colored characters. Did I tell you about my meetings with Barnes and Guillaume?21

There’s a new colored paper here in French which the Prince is putting out.22 I’ve been asked to call at the office but haven’t had a chance yet. If they want to use any of our stuff I’ll let you know so you can send something you especially like.

I think you’ve done fine with the junk I left with you. Here’s a $ to cover past postage. Keep the Southern Workman23 until I come. Don’t send to the Crisis. I’ve sent them some poems of which I’m enclosing a list. If any of them happen to be ones you have sent out, (I’ve forgotten exactly what I gave you), or ones which have been published, please notify “The Crisis” so they won’t re-use them. Don’t worry with my stuff this summer. Take a vacation.

Mother’s staying at 1200 Arctic Ave. I know she’d be glad to see you. Locke says he just missed her in Washington.

The French are very slow. After two weeks of waiting Flammarion notifies me that no more copies of |René| Maran’s first two books of poems are to be had. They’re out of print. So I’m sending you the only one I could get “Le Visage Calme.” And I’m returning Edna St. Vincent |Millay|. I hate to do it, but I imagine you like her as much as I do. Thanks. Write to me soon.

Sincerely,

Langston

TO COUNTEE CULLEN [ALS]

Paris

July 4

1924

Dear Countee:

I’ve just met René Maran and the colored prince, Kojo Tovalou. Maran says that he hasn’t even any copies of his first books himself, but that he is going to try to get them for you. He’s a darned nice fellow,—reminds me a bit of you. And talk! I don’t get a third of what he says. But it’s good practice in French so I’m going to see him often. He may come to the States to lecture next winter. I hope he does.

Send me two or three poems that you like real well. I think I can get them in “Les Continents,” and write me a little article about yourself to go along with them.24 I’ve told them who you are but I don’t know just what you’d want in a little note to go with your poems.

The Paris “Midnight Shuffle Along” opens tonight—20 colored artists. American sailors and colored Frenchmen have had several rows lately. Fists & knives. Write me, Langston

I didn’t intend for “Dream Variations” to be in The Crisis at all. I sent it to Mr. Dill in a personal letter!x*!? Now I’ll have to give Locke something else for “The Survey.”25

|August 1, 1924|

Dear Harold:

It’s fine to hear from you. I’m sorry you didn’t get over, in a way. The gardens at Versailles are worth coming from China to see,—but then home isn’t bad. And I’m glad that “ol’ divil sea” said, “—you!” Wait until you save $300 then come over and stay a few months. Don’t give up coming but let the sea alone. She’s a wicked creature.

Mr. Locke is here and we’ve been having a jolly time.26 I like him immensely. And I’ve just about “done” everything in Paris except the “Louvre” and an airplane ride over the city. I’m afraid I’ll miss those, though, because I’m going to Italy next week.

Do not write me here again. And forgive me for not writing you a longer letter now, but I have such a pile of correspondence in front of me. If I get it all answered by next August I’ll be doing well.

My “little love” from London has gone back to Piccadilly.27 And tho our hearts may be broken, they still beat.

A woman of charm is right! Miss Fauset is my own brown goddess!

Eric’s review is a terribly childish and badly written thing. And the curt impertinence of the last two sentences tempts one to want to punch him in the eye.28

I’ll send you “Song for a Banjo Dance” from my next stopping place, (wherever that might be). So long!

Sincerely,

Langston

TO COUNTEE CULLEN [ALS]

[Postcard]

Desenzano, Lago di Garda29

August 13 |1924|

Dear friend: This is where I take my daily dip. You wouldn’t believe such colors anywhere but on a post card, yet it really is here. And the sun—oh! what sun! I’m in love with Italy. This is an old up-hill town full of simple, kind people. I’d like to stay here forever,—almost. But I think I shall leave by the first.—Maran’s address: René Maran, 82 Rue de la Huchette, Paris, France.

Sincerely,

Langston

Desenzano, Brescia,

Lago di Garda, Italy,

August 24 |1924|.

Dear friend:

I understand how much the attractiveness of Italy depends upon color. Cloudy days here are as empty and devoid of beauty as those in any ordinary place. Even the lake turns gray. But when the sun shines everything is brilliant. Today there was a rare sunset, the kind that you would love. (And only the second really lovely one since I’ve been here.) The color changes lasted for more than an hour, until the various mountain ranges became merely shadows behind shadows. And the lake always a changing jewel,—blue-gold, blue, dark blue, purple, gray. If you want to stop off here for a day maybe there will be another sunset like that. Then we could go to Verona for a few hours to see the tomb of Romeo and Juliet and the arena where Duse appeared, and on to Venice.30

I wish you were here now. Your company in Paris has spoiled me for being alone.

Romeo |Luppi|’s friend from Turin is coming down tomorrow and they are expecting to leave about the twenty-ninth. If we are going to Venice, I do not want to return all the way to Turin, as that would only be a waste of good railroad fare. So I hope I hear from you soon.

You won’t forget to get my letters for me when you pass through Paris. And my book from Maran. And see that Countée |Cullen| gets some copies of the number in which his poems appear. Please.

I have just finished Madame Bovary, and think that the best thing Emma did was to kill herself. She should have done it before.

I suppose you’re enjoying the London Exposition. There must be a number of monkeys there in the African sections!

Yours sincerely,

Langston

*P. S. Your letter from Paris just came, also Claude |McKay|’s. We’ll skip Venice, if you say so, and do the Blue Coast instead so as to see McKay. But let me know. I hope he’s better.

Genoa31

Wednesday |September 1924|

Dear Friend,

How much I hated to see you leave yesterday! We really were having a delightful time together. Certainly our week in Venice was as pleasant as anything I can ever remember.

But I wish you had seen the Albergo Popolare before you left, then you wouldn’t doubt me when I say that it’s a wonder. For twenty-one lira a week one has one’s own room, a baggage locker, tax and service. And it’s very clean. Lots of German hikers are here. And it has a beautiful view. It’s on the hill way at the other side of the fort from where we were. And its windows look straight out to sea, with the harbor at one side below.

I’ve found a restaurant where it’s impossible to eat more than a five lira meal. And that’s from soup to cheese. And lovely wine. It’s a sort of family place. Yesterday my luncheon and dinner came to but seven eighty. So I’m good for at least a month here. If nothing turns up. But I worked today on the “City of Eureka.” Hung over the end on a swinging stage and painted the stern. It was fun—trying to keep from falling into the water. And I’m as “painty” as can be tonight.—$2.08.

But I like Genoa. And there’s nearly |a| full moon again. You should hear them play guitars here! Write to me. Till next time, dear friend,

Langston

Genoa, Italy

The Sailors’ Rest,

15 Via Milano,

September 25 |1924|

Dear Friend:

Still on the beach. Five of the original six have gone, so there’s only two of us here now—Americans. But there’s a wonderfully varied assortment of other beach-combers here. And of colored fellows, all the way from Porto Ricans to Abyssinians. Each with a long adventurous tale. One doesn’t have to read to be entertained here. And they have the most amusing ways of “bumming” people! One Irishman always takes off his shoes, puts them under a park bench, and runs bare-footed after the tourists. Yesterday, in his haste, he threw his breakfast away (a sandwich) thinking he was going to make a good haul. But they happened to be Germans who had no money for alms,—and no extra shoes!X! The sun’s still wonderful here, but they say it gets cold soon, and begins to rain. I could have gone to India yesterday if I’d have been a cook and a baker,—but I’m not.

I had a long letter from Claude |McKay| today, and the September Crisis. He probably won’t come down. He has too much baggage to carry. (My own is growing lighter all the time. I put the alarm clock up for sale today. And gave a shirt away to a Porto Rican friend who hadn’t any—it’s getting a bit cool.)

I’ve been reading Emerson’s essays and my Greek plays. I’ve done a couple of new poems. I have no more paper so I’m sending you one on the back of this letter.32

Be happy, dear friend. Write to me,—c/o Sailors’ Rest.

Love,

Langston

1 Hughes had left Jones Point on June 4 to take the job as a mess boy on the ship.

2 Born Carolina Mercer Langston, Carrie Clark (1873–1938) was the daughter of the abolitionist and businessman Charles Langston (1817–1892) and his wife, Mary Sampson Patterson Leary Langston (1837?–1915). Passionate about novels, poetry, and the theater, Carrie aspired in vain to become a successful actress. Her letters show that she used various forms of her first name, from Caroline to Carolyn to Carrie, as well as alternately spelled Clark with and without a final “e.” Hughes’s own “full and legal” name, as he wrote on January 21, 1960, to Arna Bontemps, is James Langston Hughes and not “James Mercer Langston Hughes,” as he called himself once, and is often called.

3 The West Hesseltine called at ports from the Azores to Lobito Bay on the Angola coast, including Lagos in what was then the British colony and protectorate of Nigeria.

4 Gwyn Clark was Hughes’s stepbrother. After her divorce from Hughes’s father, his mother, Carrie, married a sometime cook, Homer Clark, who had a son, Gwyn, by a previous union. Rebellious and a weak student, Gwyn “Kit” Clark was often a source of worry to Hughes, who nevertheless loved him as a brother. In Sierra Leone, the West Hesseltine took on men and boys from the Kru tribe to unload and load cargo as well as perform various other chores aboard the ship.

5 On October 21, Hughes returned to New York with a large red monkey named Jocko, which he had acquired in the Congo as a gift for Gwyn Clark. He writes about Jocko in The Big Sea.

6 The West Hesseltine docked in Brooklyn on October 21.

7 On February 2, 1924, Hughes had sent Locke a telegram asking for help to start at once as a student at Howard University in Washington: “MAY I COME NOW PLEASE LET ME KNOW TONIGHT WIRE LANGSTON HUGHES 234 WEST 131 ST CARE CULLEN.” Not receiving a response (Locke had mailed a letter, which apparently never arrived), Hughes sent this apology.

8 On February 5, Hughes departed on his second stint as a mess boy aboard the McKeesport, a freighter that sailed regularly between Rotterdam and New York. He observed in The Big Sea that his “second trip across was as bad as the first, so far as weather went. And worse in other respects. Several very unfortunate things happened aboard.” These things included the death of the chief engineer from pneumonia, an accidental scalding of another mess boy, and a mental breakdown of their wireless operator.

9 Hughes argued with the ship’s steward, who apparently refused to give him a piece of leftover chicken because chicken was reserved for officers. When the McKeesport reached Rotterdam on February 20, Hughes paid for a visa to enter France and took a train to Paris.

10 In Paris, Hughes met Amy and Gwen Sinclair, two sisters from Jamaica, and, from London, Anne Marie Coussey, with whom he fell in love, according to his account in The Big Sea.

11 Claude McKay (1889–1948), a poet, novelist, and editor, moved from Jamaica to the United States in 1912 and studied agriculture in Kansas and at Tuskegee Institute in Alabama. Aiming for a career as a writer (he had published two books of poetry in Jamaica), he settled in Harlem in 1914. His novel Home to Harlem (1928) is considered a major work of the Harlem Renaissance.

12 Hughes was a devoted fan of the African American singer Bessie Smith (1894–1937). Known as the “Empress of the Blues,” she has been called the most influential vocalist in the history of the blues.

13 The tenor Roland Hayes (1887–1977) was the first African American man to earn international fame as a classical concert performer.

14 Raquel Meller (1888–1962) was a Spanish actress and singer whose films include Violettes Impériales (1923) and Carmen (1926).

15 Hughes worked for Bruce, the colorful cook at Le Grand Duc nightclub in Montmartre. The club, managed by a black American, attracted a clientele that included American celebrities and even the occasional royal. Late at night, musicians and entertainers from other clubs would gather at Le Grand Duc for what Hughes describes in The Big Sea as “a jam session until seven or eight in the morning—only in 1924 they had no such name for it. They’d just get together and the music would be on.”

16 Harold Jackman (1901–1961) was a notably handsome and urbane African American schoolteacher, lover of the arts, and close friend of Countee Cullen and Carl Van Vechten. With degrees from New York University and Columbia University, he taught Social Studies in the New York public school system for thirty years.

17 In The Big Sea, Hughes recalls living for a while in a similar arrangement with a young woman he calls Sonya.

18 “Suicide Chant” appeared in Color (1925), Cullen’s first book of poetry. The poem begins: “I am the seed / The Sower sowed; / I am the deed / His hand bestowed / Upon the world.”

19 Hughes’s “Song for a Suicide” appeared in The Crisis of May 1924.

20 A proper Bostonian, William Stanley Braithwaite (1878–1962) was an African American poet and the editor of a respected annual collection of American magazine verse. Although he did not produce a volume such as the one mentioned in this letter, he included four poems by Hughes in his Anthology of American Magazine Verse for 1926. Countee Cullen dedicated his own anthology of African American verse, Caroling Dusk (1927), to Braithwaite.

21 Locke had arranged for Hughes to meet Dr. Albert C. Barnes, described in The Big Sea as “the Argyrol [a popular antiseptic] magnate, who had the finest collection of modern art in America at his foundation in Merion, Pennsylvania.” Their lunch at the Café Royale near the Louvre went poorly because the business-obsessed Barnes reminded Hughes of his father. However, Barnes arranged for Hughes to visit the home of Paul Guillaume, a well-known French collector of African art. Barnes’s art collection is now housed in a museum in central Philadelphia.

22 Prince Kojo Tovalou Houénou was the nephew of the deposed king of Dahomey (now the Republic of Benin). René Maran, a French writer of African descent, helped the prince edit Les Continents, France’s first black newspaper.

23 The Southern Workman was published by the Hampton Normal and Agricultural Institute in Virginia (now Hampton University), one of the country’s major historically black colleges. The periodical sought to document the achievements of African American educators from the end of the Civil War to the early twentieth century. Hughes’s “Danse Africaine” appeared in the April 1924 issue.

24 The July 15, 1924, edition of Les Continents included poems by Hughes (“The Negro” and “A Black Pierrot”), Countee Cullen, and Claude McKay.

25 Locke was then editing a “Negro” number of Survey Graphic, a special yearly supplement of The Survey, an influential monthly magazine devoted to national and international social problems. Locke was eager to include poems by Hughes. Although “Dream Variations” had appeared in The Crisis, Locke republished it in his special issue, which became the basis of his acclaimed anthology The New Negro (1925).

26 After corresponding for eighteen months, Alain Locke and Hughes met for the first time in Paris in late July. Locke sought to introduce Hughes to the main cultural treasures of Paris beyond the nightclubs of Montmartre.

27 In the spring of 1924, Hughes enjoyed a close friendship with Anne Marie Coussey, the daughter of a prosperous West African–born resident of London. He describes this friendship vividly in The Big Sea (1940).

28 Eric Walrond’s review of Jessie Fauset’s first novel, There Is Confusion (1924), appeared in the July 9 issue of The New Republic. His review ends: “Mediocre, a work of puny, painstaking labor, There Is Confusion is not meant for people who know anything about the Negro and his problems. It is aimed with unpardonable naïvete at the very young or the pertinently old.”

29 Romeo Luppi, a waiter at Le Grand Duc in Paris, had invited Hughes to spend August (when the club was closed) with him at his mother’s home in Desenzano on Lake Garda in northern Italy.

30 After Hughes met Locke in Verona at the end of August, they traveled together to Venice.

31 Hughes’s passport and wallet were stolen while he was traveling by train to France by way of northern Italy. Unable to reenter France without a passport, he left the train in Genoa with Alain Locke, who gave Hughes some money and headed home. Stranded, Hughes stayed in Genoa, living by his wits at times while he sought passage back to the United States.

32 On the back of this letter Hughes wrote the text of his popular poem “I, Too.”