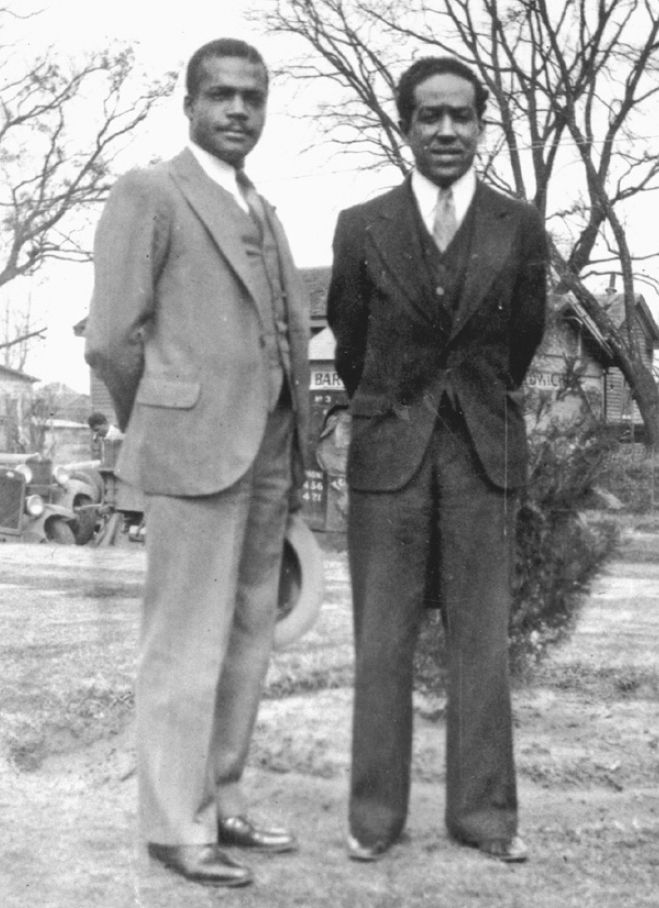

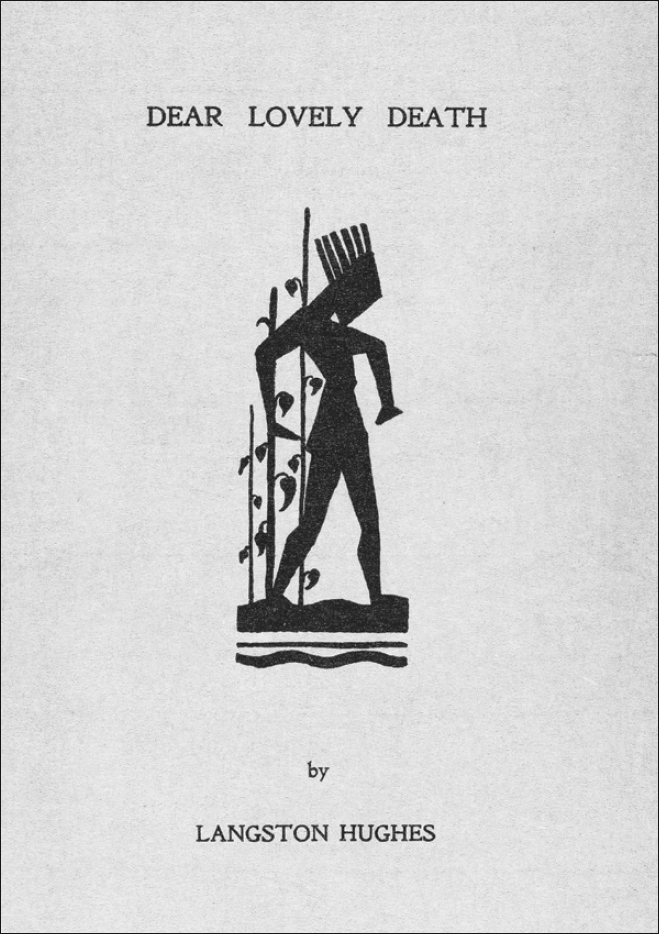

On tour with Radcliffe Lucas, 1931 (illustration credit 14)

Christ is a nigger,

Beaten and black:

Oh, bare your back!

Mary is His Mother:

Mammy of the South,

Silence your mouth.

God is His Father:

White Master above

Grant Him your love.

Most holy bastard

Of the bleeding mouth,

Nigger Christ

On the cross

Of the South.

At the suggestion of Mary McLeod Bethune, and with money from the Rosenwald Fund, Hughes toured the South and then the western United States (1931–1932) reading his work in schools and churches, taking poetry to the people. This tour helped to solidify the connection between him and a wide African American audience that would last the rest of his life. His readings would also provide him with a modest but sustaining income as he struggled to continue writing. Hughes’s commitment to the left deepened with his support of the Scottsboro Boys, nine black youths accused of raping two white women in Alabama in 1931.

Y.M.C.A.,

181 West 135th St.,

New York, New York,

August 14, 1931.

Dear Mr. Johnson,1

Just recently back from Haiti, and I found your note with the enclosure waiting for me the other day when I went after my mail. I have a lot to tell you about my impressions of the Black Republic. Would also like to talk over with you a reading tour of the South which I hope to do this fall and winter if dates and a Ford can be procured. In a Ford we came all the way from Miami for less than $20.00, so I know such a tour by car could be done cheaply. I want to help build up a public (I mean a Negro public) for Negro books, and, if I can, to carry to the young people of the South interest in, and aspiration toward, true artistic expression, and a fearless use of racial material. I am asking the Rosenwald Fund if it wishes to help me in that and in the writing of some of the many things I have in mind to do.2 I would appreciate it immensely if you would allow me to use your name should they ask me for recommendations, etc., as I suppose they will.…. I hope your summer has been an enjoyable one. I know I remember with delight the afternoon I spent at your lovely place last year with Amy Spingarn.…. I send all good wishes and best regards to Mrs. Johnson.

Sincerely,

Langston

TO AMY SPINGARN [ALS]

[On L.H. monogrammed stationery]

181 West 135th St.

New York, N.Y.,

September 24, 1931.

Dear Mrs. Spingarn,

I was happy to hear that you were back in the East again. I’m home, too, and have a lot to tell you about Haiti. I hope you had another profitable and happy time in California this year. Haiti was beautiful and strange, but depressing and very poor.…. Mr. Spingarn tells me our booklet may soon be underway, and that Zell Ingram’s drawing made a nice cut.3 He is in town for the winter now, going to the League,4 and making studies of Negro dancers. When you come to town I’d like both of you to see each other’s work.…. If I can help any on the booklet, please let me know.…. In November I’m going South on a lecture tour. The Rosenwald Fund has given me a thousand dollars to buy a Ford! Isn’t that swell?….. And I’m working on a new play. And am doing a children’s book on Haiti with another fellow.5 And have a pamphlet of dramatic recitations on racial themes coming out soon—intended for a non-literary public—with some broadsides, too.6 (You gave me the idea—with Barrel House!)7 This has been a tremendously busy month for me since my return.…. Please let me know when you’re in town. I have something for you.

Sincerely,

Langston

Dear Nancy Cunard:8

Thought your article in the CRISIS was swell.9 Also your idea of doing an international book on COLOR which I hope you will succeed in filling with new and exciting material from all quarters.10 Have been terribly busy since I got back from Haiti, and am about to leave New York again for a lecture tour of the South starting in November, but if I can help any more, I’d be happy to. Here are a lot of things enclosed from which you may select whatever you might like. Also some addresses that might be useful to you. I think there’s a lot of Negro talent in Havana, and the Cuban “son” music is grand. Zell Ingram has <many> good drawings that you might like. Write him. A girl named Pauline Murray, 437 Manhattan Ave., New York, has some poems and stories that I liked.11 Never been published. Not racial stuff, but might be worth your seeing, if she’d send you something. Also young artist, Charles H. Alston, 1945 Seventh Avenue, New York, has done some decorations for my WEARY BLUES poem that show an interesting talent.12 Completely unknown, but if you could make a few discoveries, or introduce some youngsters in your book, it mightn’t be a bad thing to do, and I believe these two show promise.… James L. Allen, 213 West 121st Street, N. Y., is probably the best photographer of Negroes in the world13.…. This month’s POETRY contains some new poems of mine from which you may select, too, if you like any of them. And of-course, you can use any from my books, if you care to, with the permission of my publishers, Alfred A. Knopf, Inc, 730 Fifth Avenue, N.Y.…. I’m sorry I wasn’t here when you were in America. Better luck <for me> next time …… With best wishes for the book,

Sincerely,

Langston Hughes

P.S. Aaron Douglas is in Paris. Perhaps you’ve met him by now.

181 West 135th Street, N.Y.

September 30, 1931.

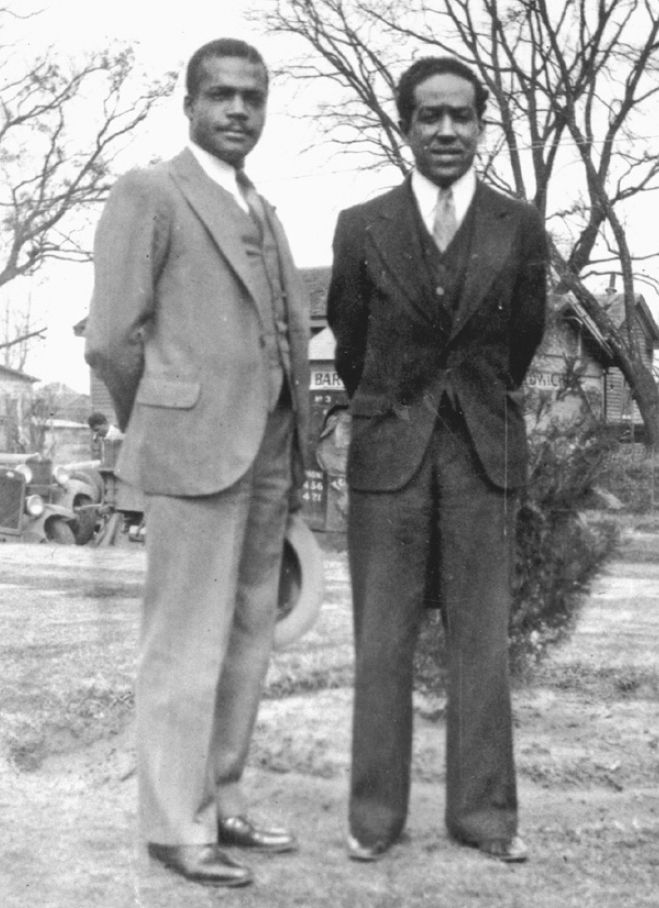

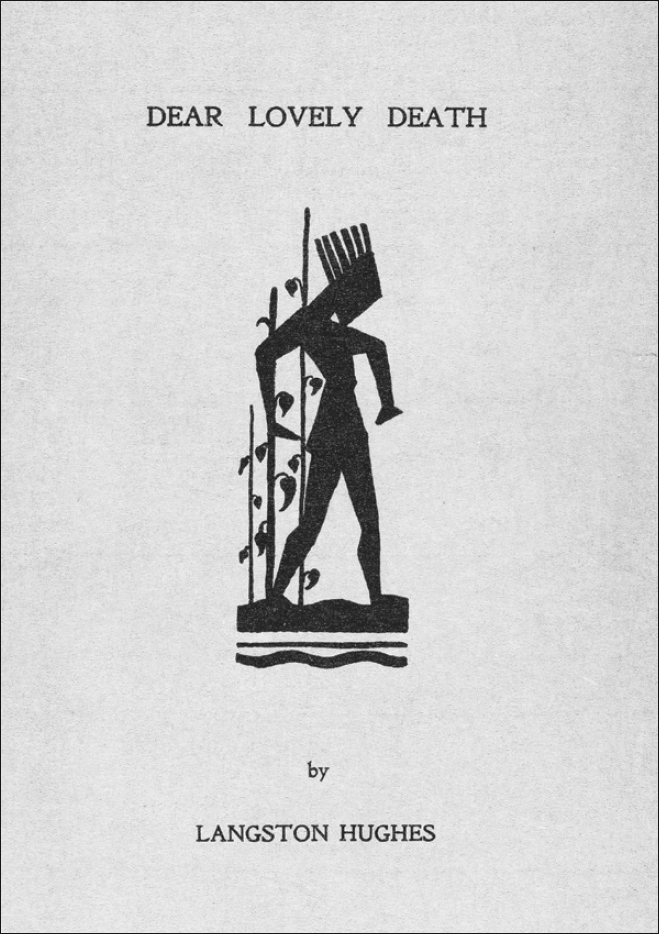

Zell Ingram’s drawing for the jacket of Dear Lovely Death (illustration credit 15)

On Tour14

High Point, NC

Dec. 8, 1931

Dear Walter,

You have my greatest sympathy in the recent death of your father. I have just heard about it from the papers.

Our engagement here in High Point has been most pleasant. This morning, I read to the various colored schools, and at the white high school. Sold gangs of books (Thanks, to you and Miss Randolph15 for the tip.).… Had a swell time in Chapel Hill, too. Paul Green had a little party for me after the reading to meet some of his friends. Then Larry Flynn (Andrew Mellon’s nephew, I learned later) opened a million bottles of home brew in my honor (Southern white ladies present at both functions). I ate dinner in one of the largest restaurants in town with the editors of Contempo. Nothing happened.16

Tomorrow Orangeburg, S. C., then return engagement at Augusta, Ga., then Florida, and, just before Xmas, your home-town Atlanta. We’re traveling every day, poeticizing at night—so haven’t much time to write. Here’s best regards to Gladys and the youngsters. Don’t work too hard. (I’m showing your picture every day to the youth of the race as one of the biggest men. That’s part of my road show.) So don’t let the race and its problems work you to death—even tho a great man becomes even greater when he dies.

Sincerely,

Langston

LANGSTON HUGHES

c/o The Crisis

69 Fifth Avenue

New York City

On Tour

Tuskegee Institute

Alabama

February 15, 1932

Miss Helen Sewell17

18 West 16th Street

New York City

My dear Miss Sewell:

I am very glad you are going to illustrate my book of poems for young people. Miss Power18 and the Knopfs are happy also.

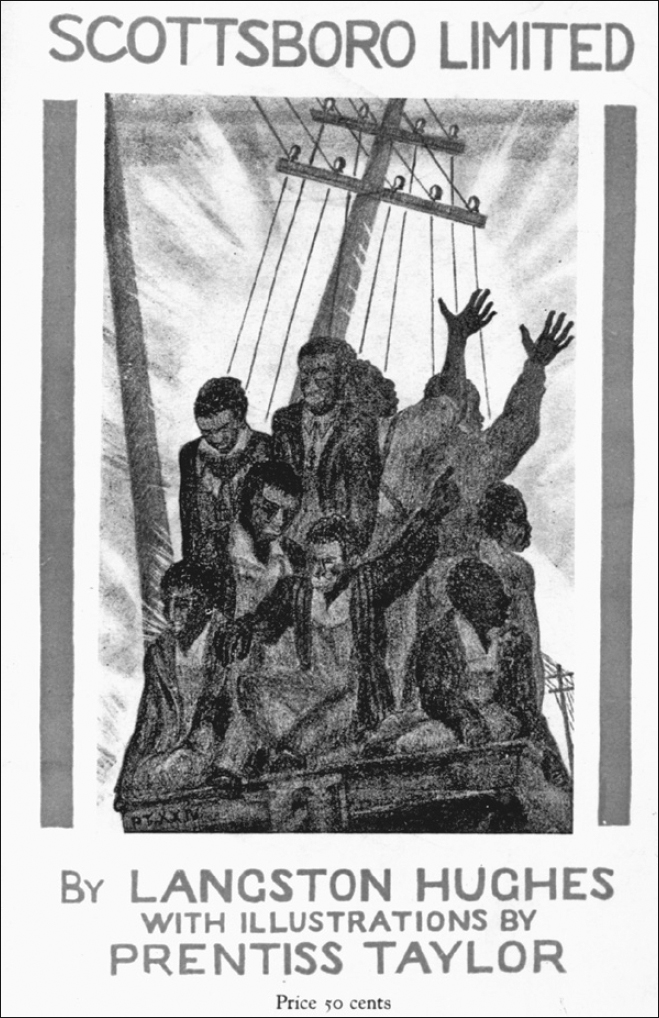

Miss Hayes19 suggests that I write you although I do not know anything that I could tell you that would help with the illustrations. Of course, if there is anything that I could tell you, you can feel free to request the information of me. The only thing I might say now is that we all hope the book will have quite a sale in the Negro schools of the South. I have been lecturing in many of those schools this winter. It seems to me that one of the great needs of Negro children is to have books about themselves and their lives that can help them to be proud of their race and to not accept the inferiority complex that many of them living in this white civilization of ours experience. I hope then that if you picture Negro children or black people in your photographs you will make them, not the usual kinky headed caricatures that most illustrators put into books of Negro child life, but I hope that they can be beautiful people that Negro children can look at and not be ashamed to feel that they represent themselves. But then I am sure you are a fine sympathetic artist and that I need not tell you this.

Sincerely yours,

LH:h

These illustrations by Helen Sewell appear in The Dream Keeper. Hughes had asked Sewell to draw “beautiful people that Negro children can look at and not be ashamed to feel that they represent themselves.” (illustration credit 16)

Tuskegee Institute

Alabama

February 15, 1932

Mrs. Mary McLeod Bethune

Bethune-Cookman Institute

Daytona Beach, Florida

Dear Mrs. Bethune:20

Of course I have been thinking about you a great deal since I left Bethune-Cookman. I am sure you must have known how I hated to leave so pleasant a place. I did not even feel like telling you goodbye that day in the dining room. I felt more like staying.

My lecture schedule has been pretty strenuous for the last month. Among other things I did ten days through Mississippi over some of the worst roads in the world, but meeting some of the most responsive groups of Negro students it has been my pleasure to read before.

At Fisk I had a long talk with James Weldon Johnson about your book and about possible people who might assist you in bringing it to pass. As to Mr. Johnson himself, there are several reasons why he cannot undertake the task. One is that he has considerable work of his own already in progress—enough, he says, for the next two or three years; another is that he feels that a woman writer might be able to do your book with greater sympathy and understanding. He suggests very strongly that you think about Jessie Fauset in connection with the matter. He feels that Miss Fauset has a thorough mastery of her style and the proper touch for an inspirational autobiography such as yours should be. Of course, she has a name in the literary world and her last book, THE CHINABERRY TREE, has been receiving splendid reviews from some of the papers. I think he might be right in his suggestion concerning your consideration of her as a person to write your book or else to work with you in doing it. Mr. Johnson feels that it would be a splendid thing to have a book about one great Negro woman by another Negro woman who has made a name for herself as a writer.

I don’t know what you will think about this yourself. I have been turning over in my mind the thought of your book in relation to myself, and whether or not I might be able to do it. This is what I think: that I could not do your book as an impersonal study of your life and do it well and with complete objectivity. I am afraid, too, that if I did it, having a personal style and tone of my own, people might expect to find the personal flavor and my own analyses of your work and your position therein. You know, of course, that I have tremendous admiration for you, but a life such as yours connected so closely with the general problems of Negro education would, if I wrote about it directly and personally, demand from me, I feel, a critical treatment that, while not in any way touching your own splendid position, might hold up to too unpleasant a criticism our entire American system of philanthropic and missionary education for the Negro, since I am becoming very critical of that system from my observation on this tour. Not that it isn’t doing good; it is. But I feel it a great pity that any group of people should have to beg for their education, and it is a worse defect in our public education systems, of course.

I feel, however, that if you would like to do your book as your own under your own name, for example, with such a title as this:

MARY MCLEOD BETHUNE

MY STORY

with, if you wish, a note or sub-title perhaps stating “as recounted to Langston Hughes”, (or whoever did most of the actual writing), that I could be of help to you in that way. The advantage of this method would be that the whole story of your life and work would have the effect of coming from your own lips and could then carry as much of the flavor of your own powerful and inspiring personality as your speeches have when you stand before an audience. At least I hope it could be written in a fashion which would convey your own force, simplicity and great sincerity. It would be then much like Jane Addams’ books,21 and I think, would perhaps have even more value to the youth than if it were written as a study of your life by someone else. Many autobiographies, you know, are not actually written by the subjects themselves. Sometimes credit is given to the actual writer, and sometimes not. In my own case, if I were to do your book in that way, it would be entirely up to you as to whether you thought it wise to name myself or not. In any case, believe me only too happy to be of service to you, if I can, in any way that I can, and certainly I hope that your book will get under way soon.

Please let me know what you think of these two ideas and whether or not you are planning to get in touch with Miss Fauset. Perhaps should the book be done in the personal manner (as your own story) Miss Fauset might be, even then, the person to do it. Being a woman, perhaps she would have greater power of putting into words some situations in your life which maybe only a woman could truly understand. Anyway I would be happy to know what you yourself think about all this.

I am enclosing my forwarding addresses for the |next| two weeks, so that you can write me without writing through New York if you would like to.

I shall never forget the cordial reception accorded me on your campus, and I send my regards to my many friends there.

With my love, I am

Sincerely yours,

LH:h

enc.

Care “The Crisis”

69 Fifth Avenue,

New York City

On Tour

Wiley College

Marshall, Texas

February 23, 1932

Mr. Prentiss Taylor22

23 Bank Street

New York City

Dear Prentiss:

A note regarding the possibility of a Scottsboro pamphlet of your declarations <I dictated “decorations!”> and my poems combined:23 Would there be a sale for such a pamphlet, or would we be doing it because we want to do it? I like the idea very much, but I would not like to do it from a commercial angle. If it were so, and I made anything from it, I would like to have it known that the proceeds were going toward either the comfort or the defense of the Scottsboro boys. Would that be agreeable to you?

As to the content, I believe I have four poems that might be included, one article, and (if you thought wise) the Scottsboro play. The booklet would hardly be, all told, as large as the “Negro Mother.” It would include, I hope, the very powerful Scottsboro drawing which you sent me at Christmas.24

The questions in my mind are these: Would Carl |Van Vechten| want to back its publication? Through what channels would we sell it? Would you like me, if we are thinking seriously of doing it, to get in touch with Theodore Dreiser’s Committee for the Defense of Political Prisoners,25 of which I am a member, or with the I.L.D.,26 to see if they would care to help us with the sales or publicity? Or would you bring it out as a limited edition with only a certain number of signed copies to sell for a price that would cover the edition and still leave something over for me to send these Scottsboro boys—if only a few cartons of Lucky Strikes?

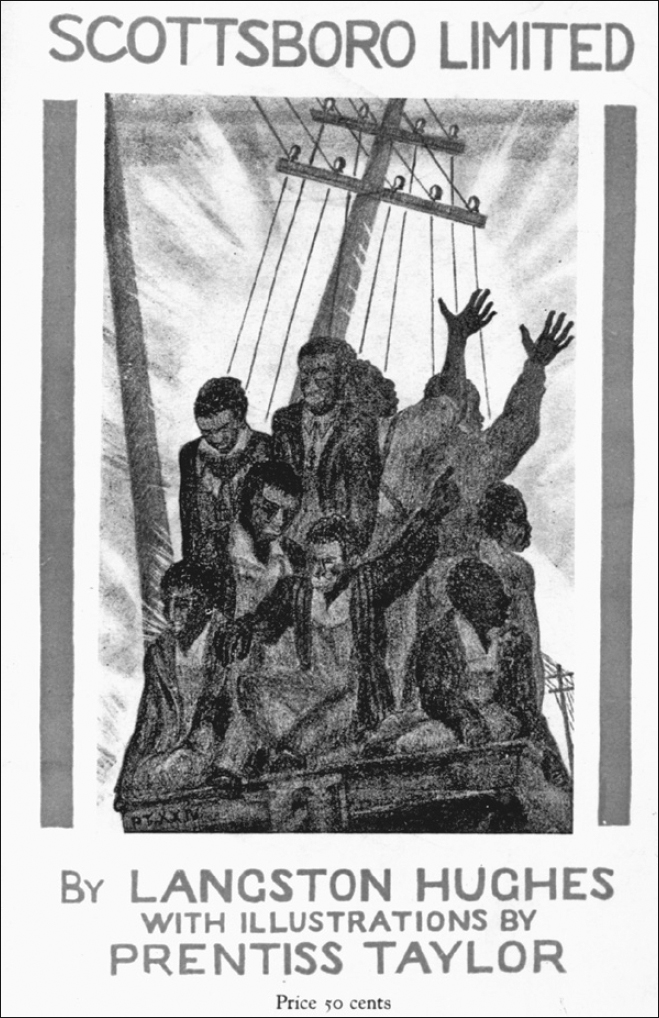

The cover of Scottsboro, Limited (Golden Stair Press, 1932)

The interest which such a booklet might help to arouse in the case would, I suppose, outweigh under any circumstances the financial returns; and that, along with the artistic reason, would be why I would especially like to do the booklet. Not being in New York, I can’t talk over these things with you, and I am so busy these days that I hardly have time to write a decent letter, but if you want to do the booklet, let me know and I shall get the material together at once. Maybe the play is too red to be included. If so, we shall use only the other things, maybe just the poems. Did you see in the Negro press the little story I wrote about visiting the boys at the prison a few Sundays ago?27 If not, I shall send you a copy.

I hope I shall receive the third edition of the “Negro Mother” soon, as we are all sold out. I didn’t answer your wire because I had just sent you a letter a day or so before, so I trust that everything is OK.

With best wishes to you, I am

Sincerely,

Langston

Langston Hughes

LH: GA

<Pardon a dictated note—but you ought to see the mail I have to answer. And no time. Mon Dieu, alors!>

<Answer at:

1227 School St.,

Y.W.C.A. Branch,

Des Moines, Iowa.>

TO EDWIN R. EMBREE [TL]

Forwarding address:

THE CRISIS,

69 Fifth Avenue

New York.

On tour,

Kansas City, Mo.,

March 5, 1932.

Mr. Edwin R. Embree,28

Julius Rosenwald Fund,

Chicago, Illinois.

My dear Mr. Embree,

On November 3rd I left New York City on my present tour of the South. With the $600.00 advanced me by the Rosenwald Fund, I bought a Ford, paid for the preliminary expenses of the tour, and started out. Since then, the tour has been paying for itself, and there has been a profit, as you see from the enclosed report, A. An itemized list of the way in which the money was expended is indicated on sheet B. And the tour route, with the states that I have covered, on sheet C. A full account of all tour incomes and expenditures has been kept, and is open to you, should you care to see it. Under separate cover, I am sending you press notices and programs in regard to the tour.

I feel that for the first time, I have met the South. I have talked with many white Southerners, and thousands of Negroes, teachers, students, and towns people. I know now attitudes and complexes I had not realized before. One is that the white people are afraid of one another in regard to things Negro: A white man of wealth speaking, “We would do a lot of things for the Negroes of this county, but the crackers won’t let us.”…… A white teacher calling me Mister in private; but Professor, Doctor, anything but Mister before her students.…. Amusing and tragic, the little things like Mister |are| not really important except as they reveal the minds behind the peonage, jim-crow schools, and lynchings.…. I spent Christmas at Huntsville where the Scottsboro girls |the accusers| live and where there are plantations all around where the Negroes haven’t been paid in a blue moon. I visited one of them Christmas day with a man who wore a red cross button in order to gain admittance to distribute fruit to kids who didn’t even know it was Christmas day.

The Negro students everywhere have been most kind to me, and seemingly intensely interested in what I had to offer them. My fees for a lecture reading of my poems have been from nothing at many grammar and high schools to $10.00 for places like Trinity that could only afford to pay expenses, to $25.00 at colleges like Rust and Piney Woods, to $50 top price for places like Talladega and Morehouse and New Orleans. Splendid crowds everywhere, and usually quite a number of white people present, even in Mississippi. I have come up now for a few engagements in the mid-west, but will return shortly to the South through Oklahoma and Texas. In April I go to California for probably ten lectures. When those are finished I want to settle down to work on my novel; then two plays; and a series of articles and short stories. There’s plenty I want to do. If the Rosenwald Fund would care to help me on a year’s creative work, I trust something worthwhile would come out of it. The main thing is to be able to pay a few months rent without worry, and to have help on typing—which takes up a great deal of time better devoted to creation. I have found several amazingly cheap cities in which one can live. They say California is cheap, too. I shall see when I get out there.

I want to thank you for your BROWN AMERICA.29 All over the South I have heard people saying good things about it; the colored students, that it is full of inspiration for them; the white people, that it is revealing and thought provoking in many ways. So you have written a book that has a meaning for both races …… Unfortunately, I haven’t read anything this winter except the poems and the manuscripts of the hundreds of brown youngsters in the South who want to be writers. I still have a brief case full of them with me now, awaiting comment. I have found a few who are really good. But your book, Miss Ovington’s30 and all the Negro novels of the season are still to be read. My tour companion reads them every night while I lecture, and tells me what they’re all about.…. He liked yours.

There is little need to say how deeply we all feel the loss of Julius Rosenwald, friend of America and of my people. Little children all over the South looked at his picture that week and were sad to know that he had gone. May my present tour, which his generosity helped to bring about, produce something worthy of his name, for I must always remember him with personal as well as racial gratitude.

On March 19th, I am to be at the C. A. & N. University, Langston, Oklahoma. I would be happy to have you send me there half of the remaining amount of my fellowship, $200.00, that I might apply it on the balance of $266.00 due on my Ford.

My New York address while on tour is: c/o THE CRISIS, 69 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y.

Sincerely yours,

Langston Hughes

[Western Union Telegram March 12, 1932]

C339 45 NL=FG KANSAS CITY MO 12

Wallace Thurman=

316 138 St. New York City

YOU HAVE WRITTEN A SWELL BOOK31 PROVOKING BRAVE AND VERY TRUE YOUR POTENTIAL SOARS LIKE A KITE BREAKING PATTERNS FOR NEGRO WRITERS I LIKE PARTICULARLY EUPHORIA’S STORY OF HER LIFE THE DONATION PARTY THE FIRST SALON AND YOUR INTROSPECTION. IT’S A REAL BOOK WALLIE THANKS=

LANGSTON.32

TO NOËL SULLIVAN [ALS]

On tour,

San Antonio,

Texas

April 8, 1932

Dear Mr. Sullivan,33

I should be happy to spend a few days with you when I come to Los Angeles (I mean San Francisco). Many of my friends have spoken so beautifully of you. As yet I do not know my coast itinerary as the bookings have been arranged by someone out there, but I will write you soon as to the time of my coming to San Francisco, as I hope to have my schedule next week.

Some of the same poems which Carpenter34 sent have also been set to music in Germany. Have you seen them? I shall bring them along.

Sincerely,

Langston Hughes

At Los Angeles

April 21st on:

c/o Loren Miller

837 East 24th Street.

On tour

837 East 24th Street

Los Angeles, Calif.

April 22, 1932.

Mr. Ezra Pound35

Via Marsala 12 Int. 5

Rapallo, Italy.

Dear Mr. Pound:

I am sorry to have been so long about answering your letter but I have been on a lecture tour of the South all winter. I was very much interested in what you had to say about Frobenius.36 Certainly I agree with you about the desirability of his being translated into English and I have written to both Howard and Fisk Universities concerning what you say and |am| sending them each a copy of your letter that was sent to Tuskegee.

Tuskegee is a very wealthy industrial school but I am afraid they have little inclinations toward anything so spiritually important as translations of Frobenius would be to the Negro race. I am enclosing here the letters with which Howard and Fisk have answered me. So you can see what they seem to think about it. They are our largest and most important Negro Universities.

Some weeks ago I sent you my books in care of INDICE.37 I hope you have received them.

I have known your work for more than 10 years and many of your poems insist on remaining in my head, not the words, but the mood and meaning, which, after all, is the heart of a poem. I never remember 10 consecutive words of anybody’s, not even my own, poems.

Thank you for bringing this great German’s work to the attention of American Negroes. I hope something will come of your suggestion and if I can do any more about it I assure you that I will.

Very sincerely yours,

Langston Hughes

1 James Weldon Johnson (1871–1938) was a highly respected poet, novelist, and lawyer who served as field secretary and general secretary of the NAACP from 1916 to 1930. His books include the novel The Autobiography of an Ex-Coloured Man (1912), the volume of poetry God’s Trombones (1927), the urban study Black Manhattan (1930), and an autobiography, Along This Way (1933).

2 Julius Rosenwald (1862–1932), the president of Sears, Roebuck and Company from 1909 to 1924, established the Rosenwald Fund in October 1917. It operated until June 1948. The fund built schools for black children in the rural South, awarded fellowships to African American scholars and artists, and also gave money to public schools and libraries. On September 17, 1931, Hughes learned that the fund had awarded him $1,000 for his proposed tour.

3 In October 1931, Amy Spingarn’s private Troutbeck Press published a limited edition of Dear Lovely Death, a booklet of Hughes’s poems with a cover designed by Zell Ingram. (“Troutbeck” was the name of Joel and Amy Spingarn’s estate in Dutchess County, north of Amenia, New York.)

4 Since its founding in 1875 on West 57th Street, the Art Students League of New York has provided classes for aspiring artists at modest fees.

5 Hughes wrote Popo and Fifina (Macmillan, 1932) with Arna Bontemps.

6 Hughes refers to The Negro Mother and Other Dramatic Recitations (Golden Stair Press, 1931), with illustrations by a young white artist, Prentiss Taylor (1907–1991).

7 Amy Spingarn made a typeset print of his poem “Barrel House: Northern City” on her own printing press. A handwritten note on the back of the print in the Moorland-Spingarn Research Center at Howard University reads: “Very rare Langston gave it to me and I printed it on my press I don’t know if it ever appeared among his poems AES.” The Lincoln News had first published the poem (a series of three sonnets) in 1928 with the title “Barrel House: Chicago.” It first appeared in book form in One-Way Ticket (1948) as “Juice Joint: Northern City” and that title has been used in all subsequent reprintings.

8 The British writer and political activist Nancy Cunard (1896–1965) was an heir to the fortune derived mainly from the Cunard fleet of luxury ocean liners. In 1920, Cunard moved to Paris, where her interest in modernist writers and in African and African American cultures deepened. Her book Black Man and White Ladyship: Anniversary, about her intimate relationship with the American musician Henry Crowder, was published in 1931.

9 “Does Anyone Know Any Negroes” appeared in the September 1931 issue.

10 Nancy Cunard’s anthology Negro (London: Wishart & Co., 1934) is a massive collection of writings on black history, culture, and social and political conditions as well as reviews of music, poetry, and the other arts. Among the contributors are Hughes, W. E. B. Du Bois, Alain Locke, Zora Neale Hurston, Samuel Beckett, and Ezra Pound.

11 Hughes helped Pauli Murray (1910–1985) to place her first published poem, “The Song of the Highway,” in Nancy Cunard’s Negro. A civil rights lawyer and legal scholar, Murray also published an admired memoir, Proud Shoes (1956). In 1977, she became the first African American woman to be ordained as an Episcopal priest.

12 Charles Henry Alston (1907–1977) started his career as a commercial artist but became a noted painter, teacher, and sculptor.

13 James Latimer Allen (1907–1977) was a well-known commercial photographer whose work remains an important record of Harlem life.

14 On November 2, 1931, Hughes and W. Radcliffe Lucas, a schoolmate from Lincoln University who served as both business manager and chauffeur, left New York on a poetry reading tour. With money from the Rosenwald Fund, Hughes had bought a new Model A Ford car. They returned to New York City on March 24, 1932. A few days later, Hughes resumed the tour when he headed for Texas with a new driver. (Hughes never learned to drive a car.)

15 Richetta G. Randolph (1884–1971?) held numerous administrative positions at the NAACP, including office manager and private secretary to James Weldon Johnson and Walter White.

16 Paul Green invited Hughes to read at the University of North Carolina in Chapel Hill. During his trip, Hughes dined with Anthony Buttita and Milton Abernethy, the young white editors of Contempo, in the dining room of a prominent café there. In I Wonder as I Wander, Hughes recalls some of the reaction to this defiance of Southern racial etiquette: “At succeeding stops in other Carolina towns my audiences were overflowing. Negroes were delighted at my having, so they said, ‘walked into the lion’s den, and come out, like Daniel, unscathed.’ ”

17 Helen Moore Sewell (1896–1957), a noted author and illustrator of children’s books, provided drawings for Hughes’s volume of poetry for young readers The Dream Keeper and Other Poems (Knopf, 1932), which he dedicated to his stepbrother, Gwyn Clark.

18 Effie Lee Power (c. 1872–1969) was director of work with children at the Cleveland Public Library and an authority on children’s books. After she suggested that Hughes publish a selection of poems for young readers, he sent her a draft of the manuscript that became The Dream Keeper and Other Poems (1932). Power later wrote the introduction to the book.

19 Most likely, Miss Hayes was employed at Knopf.

20 Mary McLeod Bethune (1875–1955), an acclaimed pioneer in the field of African American education, opened the Daytona Normal and Industrial Institute for Negro Girls in 1904. After her school merged in 1923 with one for boys, the Cookman Institute of Jacksonville, to form the coeducational Bethune-Cookman College, she remained its president until retiring in 1942. In I Wonder as I Wander, Hughes recalled the drive northward with Bethune and Zell Ingram in 1931 on his return from Haiti: “We shared Mrs. Bethune’s wit and wisdom, too, the wisdom of a jet-black woman who had risen from a barefooted field hand in a cotton patch to be head of one of the leading junior colleges in America, and a leader of her people. She was a wonderful sport, riding all day without complaint in our cramped, hot little car jolly and talkative, never grumbling.”

21 Jane Addams (1860–1935), a pioneering social worker and winner of the Nobel Peace Prize, is best known for developing Hull House, the settlement house in Chicago that became the model for many such ventures. She published two autobiographies: Twenty Years at Hull-House (1910) and The Second Twenty Years at Hull-House (1932).

22 Prentiss Taylor (1907–1991) was an illustrator and artist known for his surrealist lithographs. With a $200 loan from Carl Van Vechten, he and Hughes founded the Golden Stair Press, which was based in Taylor’s home in Greenwich Village. Their first booklet was The Negro Mother and Other Dramatic Recitations (1931), which included works by Hughes and illustrations by Taylor (see also letter dated September 24, 1931).

23 Golden Stair Press produced a booklet consisting of Hughes’s play Scottsboro, Limited, along with four poems and four lithographs on the same theme. The Scottsboro Boys were nine African American males of various ages who were falsely accused of raping two white women on a train in March 1931. After a hasty trial in April, eight of the “boys” were sentenced to death in Scottsboro, Alabama. Their case sparked international outrage. In a series of trials between 1931 and 1938, four of the defendants were acquitted. The other four were found guilty and sentenced to prison. The last was released on parole by 1950. One was pardoned by Governor George Wallace in 1967, while the other three were granted posthumous pardons by the state of Alabama in 2013.

24 The cover of Scottsboro, Limited features an illustration that Taylor dated November 1931 on a postcard he sent to Hughes. This may be the drawing to which Hughes refers in his letter.

25 The novelist Theodore Dreiser (1871–1945) was chairman of the National Committee for the Defense of Political Prisoners, which actively defended the Scottsboro Boys.

26 The International Labor Defense (ILD) was the legal arm of the communist Workers Party of America.

27 A version of Hughes’s story about visiting the defendants appeared later as “Brown America in Jail: Kilby” in Opportunity (June 1932).

28 Edwin Rogers Embree (1883–1950) was president of the Rosenwald Fund.

29 In Brown America: The Story of a New Race (Viking Press, 1931), Embree examined areas such as education, industry, and the arts. He theorized that a new brown race, a “hybrid” people who were different physically and culturally from their African ancestors, existed in America.

30 Portraits in Color (Viking Press, 1927), Mary White Ovington’s collection of biographical essays about prominent African Americans, includes one on Hughes. In 1909, Ovington (1865–1951), a white woman, had helped to found the NAACP. She served for several years as its executive secretary.

31 Thurman’s novel Infants of the Spring (Macaulay, 1932) was based in part on his life at the colorful Harlem residence (at 267 West 136th Street, dubbed “Niggerati Manor” by Zora Neale Hurston) that he, Bruce Nugent, and others had once shared. It includes a satirical portrait of Hughes as “Tony Crews,” who had published two books of poetry “prematurely.” Crews hardly ever spoke but winked and smiled a lot. He was either hopelessly shallow or “too deep for plumbing by ordinary mortals.”

32 A handwritten postscript, in French, from Carl Van Vechten appears on the telegram: “Mon cheri ami, je suis trés desolé que tu n’es pas ici mais quand je te verrai je tu donnerai les petites livres! Merci bien Van.” (“My dear friend, I am very sorry that you’re not here but when I see you I will give you the little books! Thanks a lot Van.”)

33 Noël Sullivan (1890–1956), a wealthy bachelor from a prominent San Francisco family, lived in the old Robert Louis Stevenson residence on Russian Hill. A supporter of causes such as civil rights for blacks, the abolition of the death penalty, and animal welfare, he was also a devout Roman Catholic, a trained singer, and a lover of classical music. In early March, Sullivan wrote to Hughes and invited him to stay at his home. Hughes arrived at 2323 Hyde Street on May 15, 1932.

34 John Alden Carpenter (1876–1951) was an American composer. Sullivan, a basso, had recently sung in concert a poem by Hughes that Carpenter had set to music. Among Carpenter’s works is Four Negro Songs (1926), a setting of four poems by Hughes.

35 Based in Europe, the American poet Ezra Pound (1885–1972) was a founder and key figure of literary modernism. He influenced and supported certain major writers, including W. B. Yeats, James Joyce, and T. S. Eliot.

36 Leo Frobenius (1873–1938) was a prolific German ethnologist who had traveled to Africa to study its myths and folklore. Pound, who admired Frobenius and his work, had asked Hughes whether black colleges in America might wish to underwrite an English translation of Frobenius’s volume Und Afrika sprach (“And Africa Said”) (c. 1913).

37 L’Indice was a literary newspaper based in Genoa. After Pound responded that “the Indice went bust” and that he had not received the books, Hughes re-sent them to Pound’s home.