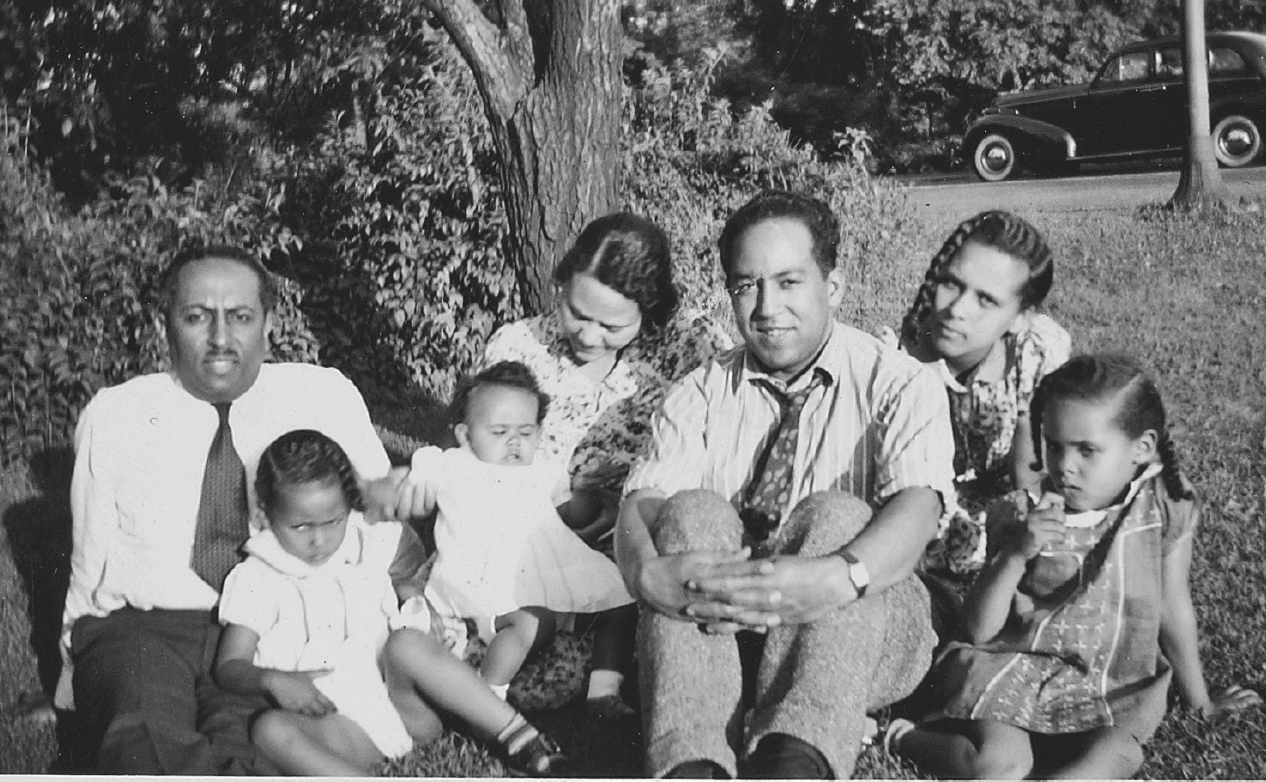

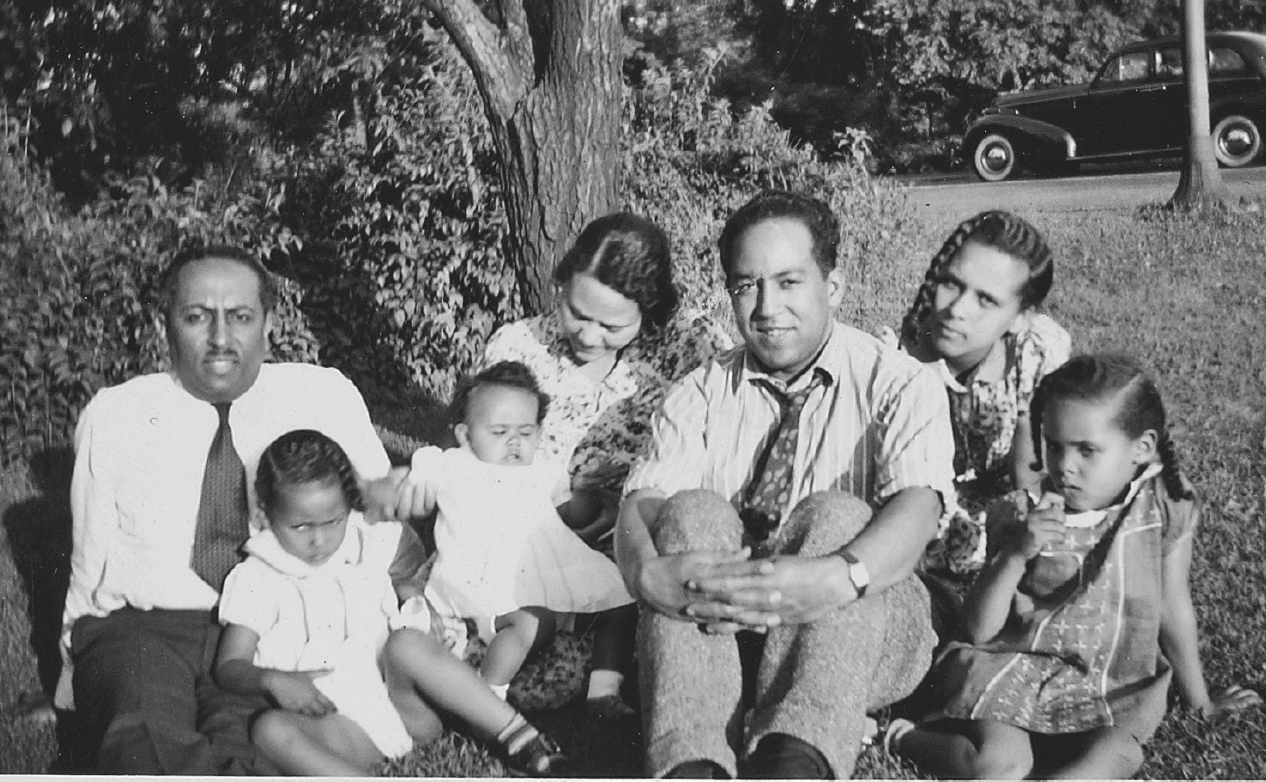

With the Bontemps family, July 1939 (illustration credit 22)

My old mule,

He’s got a grin on his face.

He’s been a mule so long

He’s forgot about his race.

I’m like that old mule—

Black—and don’t give a damn!

You got to take me

Like I am.

In January 1939, Hughes went to Los Angeles to work on a film project, Way Down South. Although this job brought him some sorely needed cash, the humiliating way in which whites in Hollywood routinely treated him and other blacks wounded him deeply. In addition, after the movie opened in cinemas in July, many liberals attacked Way Down South—and Hughes—as endorsing shabby stereotypes about blacks in the South. On the defensive, he retreated to Noël Sullivan’s Hollow Hills Farm in Carmel Valley. There he worked mainly on an autobiography, The Big Sea, which Knopf published in 1940. On its appearance, however, followers of the popular evangelist Aimee Semple McPherson loudly picketed a Pasadena hotel just before he was to publicize the book at a major luncheon there. The picketers focused on his poem “Goodbye Christ,” which denounces McPherson by name as a charlatan. The organizers canceled the talk. As negative publicity about the poem and about his political and religious views in general began to spread, Hughes holed up at Hollow Hills Farm. He lived there quietly until well into the following year, 1941.

TO NOËL SULLIVAN [ALS]

(Chicago, Ill.)1

66 St. Nicholas Pl.

New York, N.Y.

May 27, 1939.

Dear Noël,

For the past month I’ve been in seclusion in Chicago writing a book—the autobiography. I have 250 pages done—a little less than half—so I’m afraid it’s going to |be| about the size of “Gone with the Wind!”2 I’m not yet quite up to that first trip to California and the departure for Russia. I’m leaving for New York tomorrow for a month, then back to California. In the late summer, if you’d like it, I’d love to come to Hollow Hills and revise and complete the second draft there—with your help and consultation, particularly on the Carmel portions which I want to meet your approval.3 So far I’ve had a very amusing time writing it, and I hope it will make good reading to others. There |is| lots to tell!

My very best to Lee,4 Marie |Short|, the Jeffers, and Eulah |Pharr|….. In what a rush I left Los Angeles! Worked at the studio until train time, and had lectures in Kansas City 2 days later.

Affectionately,

Langston

[On Hollow Hills Farm (Carmel Valley), Jamesburg Route, Monterey, California stationery]

September 4, 1939

Mrs. Alfred A. Knopf,

501 Madison Avenue,

New York, New York.

Dear Blanche,

I have settled down in a charming little Mexican house on the side of a hill above the pear orchard here on this beautiful farm in the Carmel Valley—to finish my book. The house is entirely my own for work, and as remote and quiet a place as one would want to find, so I shall not be interrupted. I am sorry the manuscript is not ready to send you now, as I had hoped it would be, but it is going along splendidly and is two-thirds finished, so a month more of steady work should get it done. However, my difficulty at the moment is this: having turned down all lectures for this fall and put aside everything else in order to get the book done, my sources of income have temporarily ceased—and I find myself with an eviction warning from my New York landlord if I do not come through with the August rent. Which is bad enough, but not quite as bad being unable to employ a typist to assist me in the preparation of a final draft—some five hundred pages—which I shall shortly have ready to have recopied. So, much as I dislike to do it at this stage of the game, I am writing to ask you if it would be possible to now allow me an advance of $200.00 on the book, at the moment tentatively entitled THE BIG SEA and which, barring an act of God, will be ready for you in October.

I hope you had a pleasant trip to the coast. I’m sorry I didn’t get out in time to look you up. I was held up in New York doing some special song material for Marianne Oswald with Vernon Duke and Herbert Kingsley.5

My best regards to Alfred,

Sincerely,

Langston

Langston Hughes

P.S. I shall, of course, be willing to do further revision on book should you have suggestions, or find it too long, after you have read it.…. The above address good until Nov.

<COPY>

<To Roy Wilkins,

Crisis,

Sept. 20, 1939>

DEAR ROY,6

I hate to be a professional quarreler, but what you guys on THE CRISIS do to poetry is a sin and a shame. You stick it off in far corners in a column next to the ads, and put it in small type that makes it harder than it naturally is to read, and you thus hurt the poets’ souls. Poets like to be published in good spots, with lots of nice-looking margin around them that attracts the eye so somebody will look at what they have to say, otherwise they’re likely not to get looked at at all.… … But maybe you’ve reformed your make-up somewhat in your last two issues which I haven’t seen being here on a farm in the Carmel Valley finishing a book in which I shall write quite a little about the CRISIS. Perhaps portions of the book will interest you, and I shall probably send you some parts of it, in case you might like to select portions for publications.…. The enclosed poems you may return to me here in case you do not care for them. When I have others that I think you might like, I’ll send them on …… With best regards, <as ever,>

Sincerely,

Langston Hughes

TO ARTHUR SPINGARN [TLS]

[On Hollow Hills Farm, (Carmel Valley) Jamesburg Route, Monterey, California stationery]

January 20, 1940

Dear Arthur Spingarn,

Russell Jelliffe is at the Buckingham Hotel in New York this week on behalf of the Gilpin Players of Cleveland who, as you probably know, have recently lost their theatre through fire, and who are in need of immediate assistance in order to continue their activities, and to sustain them in their campaign for funds to build a new theatre.7 Mr. Jelliffe has asked me to write a few of my friends about the Gilpins. I think you already know my high regard for them. I feel that they can become the Negro Abbey Theatre. And certainly they are the ONLY permanent Negro theatre in America, and the ONLY place where Negro playwrights of talent can be sure of a chance to see their scripts tried out (and thus learn to write better in terms of living theatre). They are the ONLY colored group having (over a period of 16 years) a regular and consecutive producing program. And now that the Federal Theatre8 is gone, we need the Gilpins more than ever. The enlarged plans that they are hoping to carry through, including as they do the training of Negroes in every branch of the theatre, and the establishment of Fellowships for playwrights, etc., seem to me most important. The Jelliffes themselves have a fine free attitude about the scripts used, ranging from the religious to the radical, comedy to tragedy, folk plays to farce, and for 16 years they have fought against both the intolerance of many whites and the bigotry and ignorance of many Negroes in the Cleveland community who wanted to limit in one way or another the scope of players and their plays. But in spite of all (and a bank crash that robbed them of a laboriously built up fund) and in spite of the present fire, they’ve kept on producing. And I hope they will now find help to grow and enlarge because I think they have proven their worth and their potential (and actual) power as a force in American theatre. What they need, of course, is large sums of money to rebuild and create for themselves a center and workshop. Perhaps you can aid them in making Foundation contacts that will be helpful in this respect.

I’ve been working very hard here for the past six months on my autobiographical travelogue |The Big Sea| which Knopf has accepted and which is now just about done. I’ve also done a number of new poems and a few stories, California being most conducive to writing for me somehow. I guess it is the sunshine—and the quiet here in the country.

Please give my best to your wife and to Mrs. Amy |Spingarn|. I hope to see you all again soon as I must come East for lectures in mid-February.

Sincerely,

Langston

Langston Hughes

Hollow Hills Farm,

Monterey, California,

February 8, 1940.

Mrs. Blanche Knopf,

501 Madison Avenue,

New York, New York.

Dear Blanche,

THE BIG SEA has been sent off to you again Monday by express from San Francisco, complete except for two short chapters to be inserted when I get to New York shortly, as the material to complete them is there.

I went over the book carefully, cutting and polishing in the light of yours, Carl |Van Vechten|’s, and Ben Lehman’s comments and criticisms. It has been shortened some 50 pages, and I think thereby improved.

The portion which you liked the least has been cut one third, about thirty five pages out of a hundred in the Harlem Renaissance section. Carl, as you know, felt that most of that material was important historically and had not been written before. But I have tried to speed it up, and make it more personal, and more readable. I hope I have succeeded.…. My own feeling about that section is this: That it was the background against which I moved and developed as a writer, and from which much of the material of my stories and poems came. Also the people to whom the most space is devoted there, Carl Van Vechten, Wallace Thurman, Zora Hurston, Rev. Becton9 were people who were certainly very much a part of that era, their names known to thousands of folks. And since, I believe, a large part of the sale of my books is to readers who sort of specialize in Negro literature and backgrounds, and to schools and colleges, sociology classes, etc., it would seem to me that <that> material would be of interest. And to Negro readers as well, who would certainly give me a razzing if I wrote only about sailors, Paris night clubs, etc., and didn’t put something “cultural” in the book—although the material is not there for that reason, but because it was a part of my life. And the fault lies in the writing if I have failed to make it live. But I hope that in the revision I have bettered it.…. Many of the superfluous names have been cut, as have the excerpts from reviews of my early poems, and the <portions of the> WALDORF ASTORIA, and the chapter PATRON AND FRIEND, as you suggested. Most of the abstractions have been cut, too. So I hope you will find the whole thing somewhat better. Certainly, I have greatly appreciated yours and Carl’s help and advice.

One other observation regarding some of the material in the book and some of the names mentioned that are widely known to Negro readers (and I suppose to students of Negro life and literature): I have a large Negro reading and lecture public (as witness my annual lecture tours largely to Negro schools, clubs, etc.). For instance one could not write about life in Negro Washington without including the names I mention therein and who are nationally known to most colored people and who are very much a part of the literary and social life of colored Washington—which is, as I point out, a segregated life. I mention this so that you won’t think they’re being included as a “courtesy gesture,” they being as much a part of Negro life as Dorothy Parker would be if a white writer were writing of literary life in New York. I give you this as an example because, although I hope most of my book will <be> interesting to the general public regardless of color, some small portions of it may have vital meaning only to my own people. But that, it seems to me, would only add to the final integrity and truth of the work as a whole. And I am trying to write a truthful and honest book.10

A few minor details:

Do you think there should be an appendix of names and places?

Do you think there should be dates beneath the sub-titles of each section indicating the period covered therein, as for instance:

I. TWENTY-ONE

(1902-1923)

Do you think it will be possible (as you ask<ed> me to bring to your mind later) to get out shortly after the appearance of the regular edition, a cheaper edition (perhaps paper bound even) that might be sold exclusively by myself at lectures limited, if you wish, to Negro organizations and audiences—since many places where I speak have no bookshops in town anyhow, and most colored people cannot buy the more expensive books—but will buy them if they fall within their price range and are brought directly to them, as I do when I lecture. For several years past now, as you know, I’ve taken all my royalties in books anyhow—and probably will continue to purchase a great many of my own books to sell at lectures as long as I continue to lecture—which I guess will be a long time, as it certainly helps to sustain life.

Thanks for returning the manuscript of the poems. And for my copy of the Stevens contract.11

I’ll be in New York, I think, around the 25th or 28th at the latest. Kindly ask Miss Rubin to send all mail for me from now on to me at 634 St. Nicholas Avenue, c/o Harper, Apt. 1-D, New York, as I leave the coast day after tomorrow.

I plan to return to the coast in the early summer and write the second volume of the autobiography,12 and I hope a new novel. (But you have heard about that novel for a long while now haven’t you?) Well, all things get done in time! And it’s surely coming up.

With my best to you,

Sincerely,

Langston

Langston Hughes

[On Telluride Association, Ithaca, New York stationery]

On tour,13

Cornell College,

February 29, 1940

Dear Dick,14

I’ve been reading “Native Son” on the train. It is a tremendous performance! A really good book which sets a new standard for Negro writers from now on. Congratulations and my very best wishes for a great critical and sales success. Judging from the “New Yorker’s” early review, you’re bound to have both.

I wonder what Chicago critics (and the colored ones) will say about it? It will be fun to see.

Hastily, but

Sincerely,

Langston

P.S. I’ve been ballyhooing the book at all my lectures. Several folks want to book you to speak (naturally) but I told them I didn’t think you were engageable right now—but to write c/o Harper’s.

Hollow Hills Farm,

Monterey, California,

December 17, 1940.

(Written at Los Angeles)15

Dear Maxim,

Not dead. Nor down with flu—as is half Los Angeles. But merely entangled in that unprofitable thing known as the show business—going out to Hollywood or Beverly Hills or Hollywood every morning and not getting back to the hotel until 12 or 1 or 2 o’clock at night—since those remote districts are from where I live just about like going from Harlem to Philadelphia—and in this charming democracy of ours there seems to be no place for Negroes to live in Hollywood even if they do work out there occasionally.…. I have been intending to write you for ages and let you know how the revue is coming along, so here goes:

1. Henry Blankfort16 is (or should be) now in New York arranging to open MEET THE PEOPLE there Christmas. Address, c/o The William Morris offices. Do get in touch with him and straighten out our business.

2. We have enough material for two or three revues, both sketches and music, which we have been cutting, changing, and editing for the past six weeks. It is now only a matter of finally making up the collective mind as to just what stays in, what comes out, and how strong the social note be emphasized. It is apparently very difficult for a collective mind to make itself up. Some days it is very socially minded and most of the non-social or mildly social skits are removed from the script. A couple of days later it is somewhat more commercial and leans toward more nearly pure entertainment so the love songs go back in and the lynching numbers come out. Last night a very important audition of the material was held for about 150 writers and theatre people in Hollywood and the general opinion was that the show was too heavy, too much on the social side and not enough Negro geniality and humor for a revue that would be box-office—so today I presume we’ll swing back to entertainment. (Much of the more entertaining stuff was not done last night as the current revue committee is very socially minded and tends to insist on putting content into every last love lyric.) So

3. While the collective mind is being made up, I have decided to return to Carmel this week-end for the holidays and remain there until the general line is settled and they want to start rehearsals when, if they need me, I’ll come back, providing they vote a continuation of the $25.00 per week expense money advanced on royalties—which after this week will be down to the last $25 of the two hundred voted anyhow—and it would all have to come before their board again.

4. Personally and confidentially (to you) I do not enjoy this collective way of writing very much as I feel that when too many people are involved in the preparation of scripts, the material loses whatever individual flavor and distinction it might otherwise possess. That is probably what was the matter with ZERO HOUR.17 After everybody got their paragraph in, it was simply a depersonalized un-human editorial, well-meant but with none of the blood of life or the passion of mankind in it. I do not think plays, or even skits can be written by eight or ten people with various ways of feeling and looking at things.

5. DO YOU? Kindly answer me that as it worries me and I would like to have yours and Minna’s18 opinion on it.

6. Unfortunately, I am the only Negro writer (or Negro) on the active writing end of the committee (although William Grant Still |is| on the musical end) and it is no easy job convincing good and clever white writers that excellent and funny as much of their work is, merely putting a thing in dialect doesn’t give it a Negro or Bert Williams flavor. And that some of our material has just no feeling for a Negro or of Negroes even if it will be done by Negro actors. Since no colored writers were available here on the coast, that couldn’t be helped, however, and from a social viewpoint some really excellent stuff has been gathered together. My problem has been to guide and get it into the racial groove and keep it from having that distant and editorialized feeling heretofore mentioned. I think we have now enough material certainly for a show which would ring true.

7. As to the music, there is agreement that two or three more really hot bang up memorable tunes would be a help, but that the music, as a whole (so the group last night apparently felt) is O.K. So if you would be so kind as to call Jimmy |James P.| Johnson, Margaret Bonds, and perhaps W. C. Handy and see if they have any fresh tunes not done in shows or on the air which Henry Blankfort could hear while he is in New York or which they would care to send directly to CHARLES LEONARD,19 HOLLYWOOD THEATRE ALLIANCE, LOS ANGELES. If the tune is good, the lyrics can always be changed here on the spot to suit production ideas.

8. I have done about 15 or 20 sketches and lyrics since I’ve been here and am having them all typed up to send you. Three or four of them are apparently certain to be in the show, especially GOING MAD WITH A DIME20 which everybody seems to love and which gets a big hand and lots of favorable comment at each audition or each new committee reading. The other numbers of mine go in and come out and go in again every other day or so according to who happens to be judging material at the time. SO:

9. SINCE I LEARN THAT A SIMILAR NEGRO REVUE IS IN PREPARATION FOR THE NEW NEGRO PLAYWRIGHTS GROUP AT THE LINCOLN THEATRE following the closing of BIG WHITE FOG21 we might sell them whatever stuff is not used here, and when the script reaches you, kindly submit it to them.

10. With all this on my mind out here, it just wasn’t possible to work out anything for Moe Gale,22 as the kind of outline he would want and need with two or three really good samples would take two or three weeks of thought and preparation on my part—which I will devote to it as soon as I get back to Carmel and settled after the holidays.

11. So far I haven’t seen any sort of contract with Hollywood Theatre Alliance, unless you consider the letter you have one. I have signed nothing here (nor will I sign anything) except the checks for $25.00 weekly I’ve received which I have to sign on the back to cash and which (by the way) do not fully cover my living and transportation here, so I’ve spent here as well the income from book sales and a couple of local speaking engagements applied to living expenses while working on their revue. I have received so far six checks, $150.00 all told, and owe you commission for same which, had I been able to get two minutes ahead of the hotel bill, would have been sent you. But that being, so it seems, out of the question—since the bill presents itself regularly every Saturday even before the check arrives—would you kindly deduct said amount due you from whatever comes in on the New York end. If nothing comes in, I’ll send it to |you| myself the next time the Lord sends me a small amount of cash and I am safely at Carmel with no overhead and nothing but my art to worry about—which is a matter of soul, not material.

Charles Leonard, in charge of the show for HTA, is a swell fellow to work with, and I’ve enjoyed my experiences here very much. I do not suppose it is up to me to puzzle out how a Future Works Committee, a New Negro Theatre Board, a HTA Executive Board, a Negro Revue Committee, and Mr. Blankfort and Mr. Leonard can ever all of them and all at once agree on any one sketch or song or production idea, let alone on the 25 or 30 needed to make a show. That is why I think, now that there is certainly enough good stuff on hand to argue about from now to doom’s day, I had just as well betake myself off to the comfort and security of Hollow Hills Farm until said above collective mind is made up, as I cannot afford to stay around here indefinitely for $25.00 a week with no time or leisure for other and more lucrative (artistically at least) work which I have in mind to do this winter. DO YOU AGREE WITH ME? And if and whenever the show is set for rehearsals, if they wish me to come back and help further then, I’d be happy to do so. Or am quite willing to re-write and help edit skits and lyrics by mail if anything comes up that they need for me to assist on.

12. WHAT KIND OF AGREEMENT ARE WE GETTING FOR all this work?23 Better get Henry Blankfort to sign it while he is in New York. The revue is being produced by the HTA and they therefore must sign all papers as it is they who will raise the money, etc., and the New Negro Theatre is merely an assisting group artistically—but are broker than HTA, so be sure contracts are with Hollywood Theatre Alliance.

13. Had a long talk with Paul Robeson a few weeks ago. He liked the revue material we read him very much, is willing to be in the show here for a couple of weeks if desired to help out the project. But HTA would rather (if show is hit here) interest him in appearing in a New York company.…. If only they’d hurry and get it on before somebody else beats them to it with a Negro social revue—since the idea is now in the air.

14. From the genial efficiency of your office, I judge that you and Minna put your collective heads together and produce a single thought—but now what would you-all say is the ratio of two plus multiplied by x-y over black z divided by liberal q plus left a over the necessary b of the unified zip desired for a revue?

15. I await your answer for clarification.

Sincerely, your humble client,

Langston Hughes

Hollow Hills Farm,

Monterey, California,

December 30, 1940.

Dear Maxim,

A few days ago I sent you a copy of the words and music of AMERICA’S YOUNG BLACK JOE,24 and also the revised versions of the ballads that went to you sometime ago. I trust you have received them O.K. I am trying my best to get my desk cleared by New Year’s so I can plunge into the serialization of LITTLE HAM immediately thereafter.

Here is something I wish you could do for me, or advise me about. In its issue of December 21st, very prominently placed, (and no doubt as a result of Aimee’s doings)25 THE SATURDAY EVENING POST published without my permission, and certainly in violation of copyright, an old poem of mine entitled, GOODBYE CHRIST,26 which I had withdrawn from circulation years ago. As a result, I have issued the enclosed statement which I would like for the editors of the POST to see and publish, entirely or in part, particularly the last paragraph, if that be possible.27 What do you think? And would you be in a position to call it to their attention for me? I certainly do not choose to have Aimee and her sound trucks picketing all the lectures which I give from now on. Nor do my various sponsors.

Also would you be so good as to get from ESQUIRE the copyright to SEVEN MOMENTS OF LOVE, and from the NEW YORKER, to HEY-HEY BLUES, poems which Blanche Knopf wishes to include in my new book—sending same direct to her?28

I have almost a dozen short stories outlined which I shall send you in due time. And I also want to get off to you copies of all my revue material. Did Henry Blankfort get in touch with you, or you with him, in New York? How did MEET THE PEOPLE fare at the hands of the Broadway critics?29 If it flops I see no cullud show in Hollywood. After Moe Gale, no more show business for me—only literature. Would you not advise so, dear Maxim?

Happy New Year to you and Minna! And peace!

Sincerely,

Langston Hughes

[On Hollow Hills Farm, (Carmel Valley) Jamesburg Route, Monterey, California stationery]

Peninsula Hospital,

Carmel, California,

January 25, 1941.

Dear Dorothy,

Being ill for the past two weeks here in the hospital—an arthritis-sciatica pain in one leg that won’t let me put foot to the floor as yet30—I have thought of you often and wished I could see you. I keep thinking of the grand times we’ve had, our adventures in Conn., in the theatre with a big T, and at your delicious board with the poor dog always without the window. Tell Nicky these weeks in the hospital I sympathize with him more than ever. (In fact, if you are spiritual (can’t spell it), you must have heard me barking at your window—all the way from coast to coast! I seem to see Brooklyn—380—a lot these days.)….. I’ve really been ill since New Years—flu, worry, complications: revue, theatre, Aimee |Semple McPherson|, broke, whatnot, my doom suddenly come upon me! Anyhow, I loved your letter, which I had been waiting for a long time. And I do wish I could go to Puerto Rico this summer! Well, maybe! Spring might bring a bonanza.…. I hear the Playwrights |Negro Playwrights Company| are $10,000 (Ten!! Thousand!!!) in the hole! They have beat the Suitcase all hollow for debts! Also for committees that wrangle till dawn, I hear! Dear Dorothy, the next theatre we have will be in our own backyard. Nobody running it but us! Nobody!.…. The Los Angeles revue moves on. They phoned and wired me to come back to work, but by now evidently realize I am laid low. I’ll have some material in it, tho, no doubt. My “Mad Scene from Woolworth’s” they seem to love. Also “Hollywood Mammy”.… Well more next time. Write soon. Love, Langston

TO ARTHUR SPINGARN [ALS]

[On Hollow Hills Farm, (Carmel Valley) Jamesburg Route, Monterey, California stationery]

Peninsula Hospital,

Carmel, California,

January 30, 1941.

Dear Arthur Spingarn,

Thank you so much for your note. In it you said you had just come from the hospital. Strangely enough, the next day I went to the hospital—where I have been until now—flat on my back until this week when I have been getting up a little every day! I expect to go home, back to the farm tomorrow. New Year’s Day I took the flu. Being worried about my work in Los Angeles on a show, and little bills that needed to be met the first of the year, I guess I got up too soon. Anyway, an attack of acute arthritis laid me low so I could hardly move for 2 weeks—so here I am. But delighted to be leaving this week—altho I guess I’ll be two or three weeks really getting back to myself. And will stay here in the country.

Let us do no more about the poem.31 Knopf’s lawyer took it up, but decided to let it all drop, except to publicize my statement.

In May I shall have a new book of poems, “Shakespeare In Harlem,” on the folk and lighter side.

This June will be twenty years since my “Negro Speaks of Rivers” appeared in the Crisis. I want to do something very special for the “The Crisis”—a poem or article, for that issue. It is really 20 years of my creative career since that was my first published poem. My best to you and your wife.

Sincerely, Langston

[On Hollow Hills Farm, (Carmel Valley) Jamesburg Route, Monterey, California stationery]

February 15, 1941.

Dear Dick,

Delighted with the fact that the Spingarn Medal32 goes to you this year! Your statement to the press in acceptance was very well said indeed …… I’ve meant to thank you for a long time for sending me HOW BIGGER WAS BORN,33 but before the holidays was head over heels in the HTA Negro revue in Los Angeles, writing and re-writing songs and sketches, my own and dozens of others, as they expected to go into rehearsal the first of the year, but (as is usual in show business, left, right, colored, or white, amateur or professional) various hitches developed. I came here for the holidays, got ill with the flu and general disgustedness, got up too soon and had a relapse, went to the hospital and so am just now up and about a bit, but still house-bound.…. I was sorry to learn of the downfall of the Playwrights |Negro Playwrights Company|. It takes a terrific amount of money to run a theatre, even an amateur one, let alone professional—and cullud have got no money. This system is hardly designed to let us get much either. So for a real Negro Theatre, looks like we will have to wait until!.…. Me I am going back to words on paper and not on the stage. But I wish Ted |Ward| and the rest of you playwrights well. May your dramatization of your book be a wow—as it should be if done well. I hope I’ll be East to see it.…. Federal Music Project’s combined white and color units are doing mine and Still’s opera, TROUBLED ISLAND, about the Haitian slave revolts, in Los Angeles in April, chorus of a hundred, orchestra of seventy, Still himself conducting.34 With all those voices, they ought to sing up a breeze.

Best to you,

Sincerely,

Langston

Hollow Hills Farm,

Monterey, California,

April 23, 1941.

Dear Maxim,

Metabolism intact. Merely success deferred. None of my material is committed to anybody since we have no contract with HTA and they never made up their minds what they wanted to use of mine or made any arrangements with you or I about using it. And as you can see from the enclosed letter, it looks like they’ll just about never have a show now, at least, not a professional one, if any. So from that standpoint, I think we can feel quite free to peddle the stuff elsewhere. As to the few sketches in which Charlie Leonard is involved, I have just written him asking him to permit you to offer them for sale, and I am sure he will be willing to do so. However, there |are| only one or two such sketches, the main ones being YOUNG BLACK JOE which Leonard sometime ago gave me permission to peddle elsewhere as HTA turned it down during their last committee change. So that one is clear. He has an interest in the sketch part only of MAD SCENE FROM WOOLWORTH’S, the lyric and the song being mine with music by Elliot Carpenter.35 And I gather he is as anxious as I am to dispose of that material now. In case you would care to write him for confirmation yourself, his address is: Charles Leonard, 326 North Kilkea, Los Angeles, California.

Now, as to MOE GALE and the radio business.36 I would be delighted to come East, of course, if an advance comes forth sufficient to cover the trip. Otherwise, I am pleased to collaborate as best I can from here. You know and I know it is folly to ride any horse too hard until you get the bit in his mouth. The bit is $$$$$$, so you have been telling me lo these many years. I begin to believe you. In fact, I go farther: I do believe you. (And I know from experience that $ is the only thing that buys a train ticket.)

Re WHAT THE NEGRO WANTS,37 I recall that you used to write me every time I sent you a story that nobody would publish nary a one of them but THE NEW MASSES. And it turned out that they never saw one to publish because YOU always sold them elsewhere. So?

Next time I go to China Town I will send you a Chinese puzzle and you will see how delightful and simple they are to work compared to getting me into show business.

The government, thank God, helps out farmers, but nobody cares about playwrights. From now on I write dramatic monologues and deliver them myself under my own direction. Since you have never seen a show of mine, I will come down and give one in your office.

Metabolism intact, Jack.

Sincerely, as ever,

KINDLY RETURN ENCLOSURE.

TO ALFRED AND BLANCHE KNOPF [ALS]

Dear Alfred and Blanche,

This June marks for me twenty years of publication38—largely thanks to you as my publishers. With my continued gratitude and affection, as ever,

Sincerely,

Langston

Hollow Hills, May 17, 1941.

Hollow Hills Farm,

Monterey, California,

June 21 |22|, 1941.

Dear Carlo,

We had a very pleasant visit yesterday from Henry Miller39 at luncheon. He drove up from Hollywood with Mr. and Mrs. Gilbert Neiman.40 It turned out that Mr. Neiman has translated for NEW DIRECTIONS the same play that I did, Lorca’s BLOOD WEDDING. Henry is going to see the Jeffers today. He says he is tired of his trip and thinking of giving it up and living out here in California which he likes a great deal.…. Noël and I are delighted to hear that Fania is arriving and we very much hope she will pay the Carmel Valley a visit. I shall write her a note today.…. Judith Anderson41 is appearing at the Del Monte summer theatre in FAMILY PORTRAIT.42 And on the week-end of the 4th in the Forest Theatre in Carmel in Jeffers’ TOWER BEYOND TRAGEDY.43 I have to read it today and do a publicity piece for the PINE CONE.44 I never was much for such long poems, so I thought I would write a few letters first.…. I am so sorry to hear about Elmer Imes.45 It seems that my brother |Gwyn Clark| is in the hospital on Welfare Island46 with what he says is pleurisy.…. Tuesday I am going up to San Francisco to see CABIN IN THE SKY47 and CITIZEN CANE.48 Certainly I agree with you about Ethel Waters, and hope to do ballads about her and Mrs. Bethune, too. That you liked the BALLAD OF BOOKER T.49 and the article makes me very happy.…. Of course I will sign all the things you have unsigned when I come East in a month or so. What a wonderful title you have given the Yale collection and what a great compliment to Jim Johnson!50 I know it will furnish the basis for a collection that will grow and grow. And it must have many items in it that are unique of their kind.…. Did I tell you I had a card from Nora Holt who expects to go East soon to spend the summer with a niece in Washington, D.C.?….. And when last I saw Mrs. Blanchard51 she was thinking of going to Michigan again …… When is Barthe52 coming out? And has Dorothy |Peterson| sailed for Puerto Rico yet?….. She won’t answer letters!.…. Well, I have just heard Churchill’s speech from London.53 And I do declare! All of which will no doubt make the Communist Party change its line again. Strange bedfellows! But it’s more like Ringling’s flying trapezes. Will Muriel go all out for Britain now and she and Noël make their ideological peace?54 Will the Red Cross start sponsoring Sacks For The Soviets as well as Bundles for Britain? I’m glad I’m a lyric poet. It might be interesting to search for new rhymes for moon and June as the old ones have been worn out …… I hear the lunch bell, so,

Sincerely,

Langston

Hollow Hills Farm,

Monterey, California,

September 18, 1941.

(Clark Hotel, L. A.)55

Dear Paul,

Charles Leonard and I have just had quite a conference with Harold Clurman, producer at Columbia, and John Marc, head of the story department|,| who have expressed interest in doing a picture with you as star. Leonard and I worked out several ideas for such a picture, but the one which seems to all of us most entertaining and most “commercial”, built around a series of situations which could in no sense affront even the Solid South is, briefly, this:

The story of a great Negro singer (yourself, renamed) who wearies of the hub-bub of public life, and the trials and tribulations of an eccentric manager, gets a chance to return to the simple life when his best friend of childhood days, a Pullman porter, takes ill, is afraid if he misses his run he will lose his job, and so the singer (who greatly resembles the porter) agrees to substitute for him on the train. The main body of the picture would take place on the train, the complications of a porter’s life on a crack express, the assortment of passengers (a la Grand Hotel), the children traveling alone for whom the porter cares, who get lost and wander into town at one of the stations, the porter’s chase through the city to gather them up, the beautiful Negro maid traveling with a wealthy family with whom he falls in love, the Pullman Porters’ Quartette who, amazed at his fine voice, take up a collection to further his musical education, etc., etc. ending in the star’s manager himself getting on the train, and the attempt to hide from him who he really is.…. The whole, of course, to be tied together with a sound plot providing natural opportunities for song, and possibly ending with the appearance of the “porter” as himself, the singer, in the Hollywood Bowl.

This is, as you see, an idea at the moment, not a story. An idea based on the old “masquerade” theme with all the light and humorous implications it implies. In discussing this, Mr. Clurman felt that it might be better to not start as we had planned with the singer already famous, but to start instead at an early stage of his career, and build him up from there—keeping, however, the Pullman porter angle—which all concerned felt would be an acceptable and “natural” situation which the American public would accept and which lends itself to a mixed cast picture—not all-Negro—as the studios are wary of the latter.

Now, the studio likes the above embryo idea. As a first step before any of us go further with it, they wish to know whether or not you approve of it in general. And specifically, if so, which of the two ways of developing it seems best to you:

1. The famous singer pretending to be a porter.

2. The unknown singer as a porter working up.

In other words, do you like the general idea? Which form? A note from you on this would help Clurman to make up his mind, and to give us the go-ahead signal to develop a definite story based on the above material. Would you be so kind as to write or wire Charles Leonard, Columbia Studios, Sunset and Gower, Hollywood, at once. (Or to his home address during the week-end: 326 North Kilkea, Los Angeles, California.)

I’d love to work on a picture with you.56

Sincerely,

Langston Hughes

Dear Carlo,

Thanks for your delightfully long letter and all the nice compliments and advice. I agree with you about the second part of The Big Sea. Only I don’t want it to get so weighty that it weighs me down, too.57

|Richmond| Barthé left Los Angeles Thursday for Chicago. We enjoyed his visit greatly here. But I didn’t report it in more detail because nobody got cut, and it was just a pleasant quiet time, with some dinner parties, and teas, and cocktails. And Ethel Waters came by one Sunday morning for breakfast with Archie58 and a car full and Noël |Sullivan| took them all to call on Mrs. Blanchard.

It was too bad Eulah and I didn’t get around to having our colored party while Barthé was here. (Eulah Pharr is Noël’s housekeeper, and a very charming person who’s been with him for twelve years or more.) But we had it Thursday, cocktails 3 - 6, except that it lasted from 3 to 3 in the morning—and nobody made a move to go home before midnight, and then didn’t go. The joint jumped. We had about 50. And played plenty Lil Green.59 Everybody was dressed down, and most proper in a gay manner, and nobody got too high or anything, except one girl got mad when she heard her soldier boy intended to take another girl home, so she simply pulled all the wires out of his car so it wouldn’t budge—which left him and six other members of Uncle Sam’s citizen army stranded out here in the country, and they had to be taken back to Fort Ord in our station wagon just in time to hear “reverie” blow in the morning.

Your paragraph on the art of illustration was most interesting. And I am sure the Kauffer drawings are charming.60 But still, if they come out with NO hair on their heads—after all the millions that have been spent with Madame Walker and Mr. Murray61—my Negro public—whom I respect and like—will not be appreciative. I wrote as much to Blanche |Knopf| when I first saw the samples. Harlem just isn’t nappy headed any more—except for the first ten minutes after the hair is washed. Following that the sheen equals Valentino’s and the page boy bobs are as long as Lana Turner’s.62 And colored folks don’t want no stuff out of an illustrator on that score. Even Lil Green has finger waves. And if some of the ladies in SHAKESPEARE IN HARLEM don’t have them, too, I will catch hell—in spite of whatever “strictly, personal illumination emanates from the painter.” Do you get me?

Hughes objected to E. Kauffer McKnight’s sketches used by Knopf to illustrate Shakespeare in Harlem. These illustrations by McKnight appear, respectively, opposite the poems “50-50,” “Shakespeare in Harlem,” and “Southern Mammy Sings.” (illustration credit 23)

I’m sure Henrietta Bruce Sharon is white.63 But since I couldn’t swear it, I’ve asked Arna |Bontemps| to let you know. (But she draws heads and feet as if she were.)

Duke’s I GOT IT BAD is good. But unfortunately the words aren’t mine. They’re by Paul Webster, the white chap who wrote most of the show.64

No, Mamie Smith65 didn’t get her throat cut. She just lost her contract.

Why, I will tell you when I see you. (Leaving space at the bottom of this here letter for annotation.)

I am now on my way to hear Lotte Lehman sing.66

Ere I lay me down in questa tomba obscura I shall try to find all your letters for Yale, but they are in so many various files, boxes, suitcases, and trunks stored from here to yonder that I shall start here to finding recent ones tomorrow.

To whom are you giving your Mary Bell’s?67

The blues seem to be coming back in a big way. Every club out here now has a blues singer as a part of the floor show. And Joe Turner68 was the hit of the recent Duke show, pulling it out of polite prettiness.

Did I tell you I did a libretto of THE ST LOUIS BLUES for Katherine Dunham, a danceable story woven around the song?69 Hope she uses it. But she rather thinks she ought to do Latin American things—Cuba, Brazil, etc. Easier to sell to concert managers and Hollywood.

So,

Sincerely,

Langston

< November 8, 1941>

1 Finding Hollywood disturbingly hostile to blacks, Hughes completed his work on the screenplay for Way Down South and left Los Angeles. In early April, he joined Arna Bontemps on a lecture tour, then returned with him to Chicago, where Bontemps lived.

2 Margaret Mitchell’s best-selling novel, Gone with the Wind, was published in 1936. The film version appeared in 1939.

3 Sullivan had relocated from San Francisco to rural Carmel Valley, inland from Carmel-by-the-Sea. He settled in a spread he called Hollow Hills Farm. As with his Carmel cottage, Ennesfree, he took the name from a poem by the Irish writer William Butler Yeats.

4 A young Canadian, Leander “Lee” Crowe (1905–1989) was a close friend of Noël Sullivan. Crowe, who lived at Hollow Hills Farm, wrote short stories and poems and published his column “The Crowe’s Nest” in The Carmel Pine Cone.

5 Born in France, Marianne Oswald (1901–1985) was the stage name of Sarah Alice Bloch, who gained fame singing in Berlin cabarets but fled to Paris in the early 1930s because of rising anti-Semitism. During World War II she lived in the United States. Vernon Duke (1903–1969) and Herbert Kingsley (1882–1961) were composers.

6 In 1934, Roy Wilkins (1901–1981) replaced W. E. B. Du Bois as editor of The Crisis, the monthly magazine of the NAACP. Wilkins became executive director of the NAACP in 1964.

7 Karamu House, the Gilpin Players’ theater, was destroyed by fire in 1939. In 1949, it was rebuilt and expanded to include two theaters, exhibition space, and dance and visual arts studios through the support of the Cleveland philanthropist Leonard C. Hanna, Jr. (1889–1957), and the Rockefeller Foundation.

8 The Federal Theatre Project, part of the Works Projects Administration of President Roosevelt’s New Deal, ran from 1935 to 1939. A unit of the Federal Theatre was located in Harlem. Hughes worked later with Clarence Muse, the director of the Negro Unit of the Federal Theatre Project in Los Angeles, on St. Louis Woman, a musical version of the play by Arna Bontemps and Countee Cullen based on Bontemps’s novel God Sends Sunday (1931).

9 A controversial figure, Rev. George Wilson Becton (1890–1933) held profitable revivals regularly at the Salem Methodist Episcopal Church in Harlem (where Countee Cullen’s father had once been pastor). In The Big Sea, Hughes characterized Becton as “a charlatan if ever there was one.”

10 The Harlem Renaissance section of The Big Sea would come to be seen as an invaluable source of firsthand information on the period.

11 On January 30, 1940, Blanche Knopf sent Hughes a contract signed by George D. Stephens and a representative of Knopf for a screenplay based on Hughes’s story “Rejuvenation Through Joy,” from The Ways of White Folks (1934). Nothing came of the project.

12 The second volume, I Wonder as I Wander, was published by Rinehart in 1956 after Blanche Knopf declined Hughes’s proposal for the book.

13 On February 10, Hughes left Hollow Hills Farm to begin a poetry reading tour, with his first stop in Downingtown, Pennsylvania. He then went on to New York, Kentucky, Ohio, Tennessee, West Virginia, Illinois, and Michigan. On May 8, Hughes gave his last lecture and ended his journey in Chicago, where he stayed with Arna and Alberta Bontemps.

14 Richard Wright (1908–1960) was born outside Natchez, Mississippi. His mother was a schoolteacher, and his father was a sharecropper. He moved to Chicago in 1927 and then to New York in 1937 to run the Harlem Bureau of the communist Daily Worker. Wright’s first novel, Native Son (Harper & Brothers, 1940), was a best-seller after the Book-of-the-Month Club chose it as a main offering. Set in Chicago, it tells of a young black man sentenced to death after killing two women. Also chosen by the club, Wright’s autobiography, Black Boy (Harper & Brothers, 1945), was another best-seller. He thus became the most acclaimed and financially successful black writer in the United States.

15 In November, Hughes went to Los Angeles to work on a “Negro Revue” with Donald Ogden Stewart (1894–1980) for the leftist Hollywood Theatre Alliance (HTA). He was the only black writer creating material for the review. Although he disliked the work, he stayed on because he needed money and hoped to write a hit song. In mid-December, Hughes quietly left Los Angeles to return to Carmel. Two weeks passed before the HTA noticed his absence. The HTA asked him to return to the project, but Hughes remained in Carmel.

16 The screenwriter Henry Blankfort (1904–1993) was director of the Hollywood Theatre Alliance. Blankfort cowrote and served as stage manager for the HTA’s Broadway production of the labor revue Meet the People, which opened that year in December. In the 1950s he would be blacklisted for alleged communist affiliations.

17 The melodrama The Zero Hour (1939) tells the story of a young aspiring actress, the producer who mentors and then weds her, and the circumstances leading to his suicide.

18 Minna Zelinka (c. 1909–2011) worked for Maxim Lieber’s agency. She became his third wife in 1945.

19 Charles Leonard, born Chaim Leb Eppelboim (1900–1986), a successful screenwriter, was a member of the radical wing of the Hollywood Theatre Alliance. He was blacklisted after he was named as a communist in testimony heard by the Senate Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations of the Committee on Government Operations, the official title of the controversial unit that Senator Joseph McCarthy (1908–1957) chaired from 1953 to 1954.

20 Hughes’s sketch “Going Mad with a Dime” (or “Mad Scene from Woolworth’s”) is about a woman who goes to a dime store with only ten cents. In 1941, a song based on this sketch was briefly included by Duke Ellington (1899–1974) in his musical revue Jump for Joy (see letter dated November 8, 1941). This song was not a hit, and Ellington cut it from the revue after Hughes and Leonard approached him about royalties.

21 In May 1940 Abram Hill (1910–1986) formed the Negro Playwrights Company with Hughes, Richard Wright, Ralph Ellison, and Ted (Theodore) Ward (1902–1983), among others. Their first and only production was Ted Ward’s Big White Fog at the Lincoln Theater in Harlem in 1941. Ward wrote the play with support from the Federal Theatre Project in 1938.

22 Moe Gale, born Moses Galewski (1899–1964), a producer and talent agent, invited Hughes to develop a radio series based on Little Ham, his comedy about the numbers racket. Gale had opened the famous Savoy Ballroom in Harlem, a nightclub where whites and blacks mingled. On March 12, 1941, Hughes would send Lieber and Gale an outline for sixty-five episodes of “Hamlet Jones.” Hughes stood to make as much as $400 a week if Gale found a major sponsor. However, Hughes was once again disappointed; no such sponsor came forward.

23 As sketch director, Hughes was to be paid a royalty of one half of one percent of the gross, plus separate payments for original material. He received a weekly advance of $25 against these future royalties.

24 Hughes wrote “America’s Young Black Joe” for the “Negro Revue” project of the Hollywood Theatre Alliance. The song was for a skit about the heavyweight boxing champion Joe Louis (1914–1981).

25 Aimee Semple McPherson (1890–1944) was a notorious California evangelist who founded the International Church of the Foursquare Gospel. On November 15, 1940, when Hughes visited Pasadena to appear at a literary luncheon and promote his new book, The Big Sea, members of her church loudly protested and passed out leaflets near the site of the event. The leaflets, which included the text of “Goodbye Christ,” denounced Hughes as a communist. The luncheon was canceled.

26 Hughes’s radical poem “Goodbye Christ” attacks the gross commercial exploitation of religion by certain leading evangelists. The poem was first published, without Hughes’s permission, in Negro Worker (November/December 1932). It was also included in Nancy Cunard’s anthology Negro (Wishart & Co.: London, 1934). The leaflet from Aimee Semple McPherson’s demonstration that included the text of “Goodbye Christ” was reprinted in The Saturday Evening Post (December 21, 1940), again without Hughes’s permission (the magazine is named in the poem).

27 Hughes also sent his statement to the Rosenwald Fund, Knopf, and the Associated Negro Press, among others. In it, he described himself as “having left the terrain of the ‘radical at twenty’ to approach the ‘conservative at forty.’ ”

28 Hughes’s forthcoming book of poems was Shakespeare in Harlem (Knopf, 1942).

29 Meet the People was a satirical labor stage revue that played in San Francisco, Chicago, and New York. The Broadway production opened on December 25, 1940, and ran for 160 performances. The 1944 film took its title from the stage revue but lacked its pointed political message.

30 Hughes had claimed to be suffering from flulike symptoms for some weeks. When his illness worsened, he entered the Peninsula Community Hospital nearby on January 14. Hughes wrote to friends that he was ill with sciatica or arthritis, but hospital records show that he was diagnosed as suffering from gonorrhea. Following his release from the hospital on February 1 (his thirty-ninth birthday) he returned to Hollow Hills Farm.

31 Hughes had sought legal advice regarding a possible lawsuit against The Saturday Evening Post for its unauthorized publication of his radical poem “Goodbye Christ” on December 21, 1940. An attorney for Knopf advised against pursuing a lawsuit, and Hughes dropped the idea.

32 Joel Spingarn, then chairman of the NAACP, created the Spingarn Medal in 1914. Since then, the NAACP has awarded this gold medal annually (with the exception of 1938) to a distinguished African American. Wright received the award in 1941.

33 Wright had given Hughes a copy of “How ‘Bigger’ Was Born; the Story of Native Son” (Harper & Brothers, 1940), a pamphlet based on his lecture on March 12, 1940, at Columbia University. Subsequent editions of Native Son included this essay.

34 By 1941, the Federal Music Project (1935–1939) had been restructured as the WPA Music program (1939–1943). The WPA funding was discontinued, and this production of Troubled Island did not occur. The opera was not staged until 1949.

35 Elliot Carpenter (1894–1982) was an American composer, lyricist, and music arranger.

36 By June Hughes would learn that Gale could not find a major sponsor for the serialization of Little Ham.

37 In his essay “What the Negro Wants,” Hughes identified seven things that Negroes wanted: the chance to earn a decent living; decent housing; equal educational opportunities; participation in government; fairness under the law; common courtesy; and social equality—the end of Jim Crow. Louis Adamic (1899–1951) published the essay in his new magazine Common Ground, which was devoted to questions about multiracial and immigrant cultures. It appeared in the Autumn 1941 issue.

38 Hughes dated his career as a writer from the appearance of “The Negro Speaks of Rivers” in The Crisis in June 1921.

39 The American writer Henry Miller (1891–1980) is most famous for his sexually explicit novels Tropic of Cancer (1934) and Tropic of Capricorn (1939), published in Paris where Miller had been living. He spent three years touring the United States, gathering material for his nonfiction book The Air-Conditioned Nightmare (1945). During this trip Miller met Hughes and first saw the scenic Big Sur region (which starts about twenty-five miles south of Carmel). He would later settle there.

40 Gilbert and Margaret Neiman were friends of Henry Miller who moved to Big Sur in 1945 and lived next door to Miller at Anderson Creek. New Directions published Neiman’s translation of Blood Wedding in 1939. Hughes translated Blood Wedding in 1938, but his version would not be published until 1994, after his death (see also letter dated August 30, 1938).

41 Judith Anderson (1897–1992) was an Australian stage and screen actress who enjoyed success on Broadway and in Hollywood from the 1930s through the 1950s. Anderson was married to Noël Sullivan’s Berkeley friend Ben Lehman from 1937 to 1939.

42 The 1939 Broadway production of the drama Family Portrait (1939) by Lenore Coffee and William Joyce Cowen starred Judith Anderson.

43 Based on Aeschylus’s Oresteia, Robinson Jeffers’s poetic drama Tower Beyond Tragedy was staged in Carmel with Judith Anderson as Clytemnestra.

44 Founded in 1915, The Carmel Pine Cone is a local weekly newspaper.

45 Once married to Nella Larsen, Elmer Imes (1883–1941), a research scientist, was one of the first African Americans to earn a Ph.D. in physics. He died from throat cancer on September 11, 1941.

46 Welfare Island, in the East River of New York City, has been known as Roosevelt Island since 1973.

47 The all-black musical Cabin in the Sky by Lynn Root (book), John La Touche (lyrics), and Vernon Duke (music) opened on Broadway in 1940, and then went on a tour that ended in Los Angeles in 1941. A film version directed by Vincente Minnelli and starring Ethel Waters, Eddie “Rochester” Anderson, and Lena Horne was released in 1943.

48 The masterpiece Citizen Kane (1941) was the first feature film directed by Orson Welles (1915–1985), who also produced it, starred in it, and cowrote the screenplay.

49 Hughes’s “Ballad of Booker T.” (about Booker T. Washington) was published in Southern Frontier (July 1941) and Common Sense Historical Review (May 1953).

50 In 1941, Carl Van Vechten founded the James Weldon Johnson Memorial Collection of Negro Arts and Letters at Yale University (it opened formally in 1950). Johnson, one of Van Vechten’s dearest friends, died in 1938 when a train struck his car near his summer home in Maine. Hughes agreed at once to donate all of his papers, including his correspondence, to the JWJ Collection at Yale. Over the years until his death, he regularly sent batches of material to Yale.

51 Van Vechten’s cousin Mary Blanchard (Mrs. Frederic Mason Blanchard) was then living in Carmel.

52 Richmond Barthé (1901–1989) was a well-known African American sculptor. The Whitney Museum of American Art bought his sculptures Blackberry Woman (1932) and African Dancer (1933).

53 Presumably Hughes refers to the June 22, 1941, radio address by Winston Churchill about the German invasion of the Soviet Union, in which Churchill said that “[t]he Russian danger therefore is our danger and the danger of the United States, just as the cause of any Russian fighting for his hearth and home is the cause of free men and free people in every quarter of the globe.”

54 The poet Muriel Rukeyser (1913–1980) had met Sullivan a number of times in the San Francisco area. Sullivan was not sympathetic to the radical left, and in a letter to Ella Winter he strongly criticized Rukeyser after he heard that she had written in favor of the Soviet invasion of Finland.

55 After visiting Phoenix in August, Hughes returned the following month to Los Angeles to try yet again to break into the highly segregated Hollywood screen industry. Failing again, he retreated to Carmel.

56 Eslanda “Essie” Robeson responded on October 6 that “Paul was nervous of the rags to riches idea” and wondered if the hero could not be a worker. She continued, “What Paul really wants … is an American picture not built around him, … like, say Grapes of Wrath.” Nothing came of the film project.

57 Van Vechten had advised Hughes in his letter of November 4 that “the second volume of your life will have to be more weighty than the first. It should, I think, seriously discuss the plight of the Negro (and the hopes) in modern America.”

58 Probably Archie Savage (1914–2003), an African American dancer who had appeared with Ethel Waters in the touring production of the musical Cabin in the Sky. In 1944, he was convicted of stealing from Ethel Waters.

59 Lil Green (1919–1954) was an African American blues singer and songwriter.

60 Blanche Knopf had selected E. McKnight Kauffer (1890–1954) to illustrate Shakespeare in Harlem. Her choice distressed Hughes because the black people in Kauffer’s ten sample sketches all had unstraightened or “nappy” hair, which was then unfashionable in the community.

61 Madame C. J. Walker developed a line of hair-care products aimed mainly at black women. Murray’s Pomade was popular among black men.

62 Rudolph Valentino (1895–1926) and Lana Turner (1921–1995) were Hollywood stars.

63 Henrietta Bruce Sharon illustrated Arna Bontemps’s anthology Golden Slippers (1941). She was indeed white, as Hughes surmises in his letter.

64 Duke Ellington’s show Jump for Joy grew from the “Negro Revue” Hughes had worked on for the Hollywood Theatre Alliance. Opening on July 10, 1941, in Los Angeles at the Mayan Theater, Jump for Joy ran for 122 performances. The hit song “I Got It Bad (and That Ain’t Good),” with music by Ellington and lyrics by Paul Webster (1907–1984), originated in this revue.

65 On August 10, 1920, Mamie Smith (1883–1946) became the first black vocalist to record a blues song. Her recording, “Crazy Blues,” is said to have sold 75,000 copies within a month.

66 Fleeing the Nazis, the German opera singer Lotte Lehmann (1888–1976) immigrated to the United States in 1938. She sang at the San Francisco Opera and at the Metropolitan Opera until 1945. Her last public recital was in 1951.

67 Hughes refers to letters between the African American artist Mary Bell (1873–1941) and Carl Van Vechten. The letters are in the James Weldon Johnson Memorial Collection in the Beinecke Library at Yale University.

68 The great blues shouter Big Joe Turner (1911–1985) went to Hollywood in 1941 as a performer in Duke Ellington’s Jump for Joy revue.

69 Katherine Dunham (1909–2006), a noted dancer and choreographer, blended traditional ballet and modern dance techniques with African and Caribbean styles. Dunham founded the Negro Dance Group in Chicago in 1937, then moved her company to New York City in 1939. Hughes’s first draft of the libretto for “St. Louis Blues” is dated September 10, 1941. He outlined four potential ballet scenarios for Dunham.