![]()

Nothing can bring you peace but yourself.

—RALPH WALDO EMERSON

In the wake of World War II and the advent of the atomic bomb, Albert Einstein posed what he believed was the most important question for each of us: “Is the universe a friendly place?” “This,” Einstein declared, “is the first and most basic question all people must answer for themselves.”

Einstein reasoned that, if we see the universe as basically hostile, we will naturally treat others as enemies. On the collective level, we will arm ourselves to the teeth and react at the first provocation. Given the weapons of mass destruction at our disposal, we will eventually destroy ourselves as well as all life on Earth. If we see the universe as friendly, however, we are more likely to treat others as potential partners. We are thus more likely to get to yes with others, beginning with those closest to us at home, at work, and in the community—and then extending the process out to humanity itself. In other words, the answer we give to this all-important question is self-confirming. Depending on our response, we will behave differently and our interactions will likely have diametrically different outcomes.

In my negotiation classes, I teach about the power of reframing, the capacity each of us has to give a different interpretation or meaning to the situation. In every challenging conversation or negotiation, we have a choice: Do we approach the negotiation as an adversarial contest in which one party wins and the other loses? Or do we approach it instead as an opportunity for collaborative problem solving in which both sides can benefit? We have the ability to reframe each difficult conversation from an adversarial confrontation into a cooperative interchange between partners. The best way to change the game is to change the frame.

But reframing isn’t always easy. Even when we see the merits of a win-win approach to negotiations, it is all too easy in the heat of a conflict to fall into the trap of win-lose thinking and to see the other side—a boss, a colleague, a client, even a spouse or child—as an adversary in a fight for scarce resources, whether it is money, attention, or power. Almost everyone has a fear of scarcity, and when that fear dominates us, getting to yes becomes tough.

So where can we get some help to be able to reframe? As I have come increasingly to appreciate, the ability to reframe the external situation comes first from an ability to reframe our internal picture of life. If we truly wish to shift from an adversarial to a cooperative approach in our interactions with others, we would do well to ask ourselves Einstein’s fundamental question. What is our working assumption? Can we think, act, and conduct our relationships as if the universe is essentially a friendly place and life is, in fact, on our side?

It is not always easy, particularly in the midst of adversity, to see life as being on our side. During the time I was writing this book, I was serving as a negotiation adviser to the president of a country that was afflicted by a long-running guerrilla war in which hundreds of thousands had died and millions had become refugees. The president wanted to start peace talks in order to explore the possibility of a negotiated end to the war, but there was a great deal of political opposition to the idea of talking with the guerrillas who were branded as “terrorists.” The president wanted an agreement on a clear and limited agenda with the guerrillas before he would announce the beginning of peace talks; and, in order to reach this preliminary agreement, secret in-depth conversations needed to take place with the guerrilla leadership.

The president and his team were faced with a problem: how could they “extract” a guerrilla commander from his jungle headquarters and fly him to a third country where these preliminary secret talks could be held without anyone’s knowledge? No one could find out about this operation—not the media, not the police, and not even the army, who would certainly try to destroy the guerrilla headquarters if they knew where it was. For this highly delicate and dangerous mission, the president charged a man I will call James. James’s task was to hire a private helicopter and fly in it to a secret meeting place in the middle of a jungle clearing to pick up the commander.

When James’s helicopter finally landed in the designated location, no one was there, but, within minutes, it was swarmed by hundreds of guerrillas emerging from the jungle, each carrying an AK-47 machine gun, all of which were aimed directly at the helicopter with James inside it. He could hear many of the guerrillas shouting excitedly to their commander that this whole arrangement was a fatal trick. The level of tension and distrust was extremely high.

It is not hard to imagine just how hostile and frightening the situation must have seemed to James. What could he do to defuse the situation? Some days after the event, he told me that after a few moments of sitting in the helicopter, nervous and unsure of what to do next, he had an idea. He opened the door, stepped out of the helicopter, walked boldly up to the enemy commander, stretched out his hand, and confidently announced: “Sir, I am now placing you under the personal protection of the president!”

In that tense moment when James found himself the target of hundreds of machine guns, he had a choice: he could choose to see the other side as hostile—and given the circumstances few of us would fault him if he did—or he could choose to see the other side as his partner. James chose the latter, and because he treated the enemy commander as a partner, the commander was able to treat him as a partner too. After a brief pause to say good-bye to his comrades, the commander boarded the helicopter, and the secret preliminary peace talks began soon thereafter in a foreign capital. Six months later, a preliminary agreement in principle was announced and full-fledged peace negotiations began.

I asked James what gave him the ability to reframe that dangerous situation and he told me he had a fundamental trust in life, an assumption that it would all somehow work out. Because he saw life as his ally, James could see the commander as his unlikely partner.

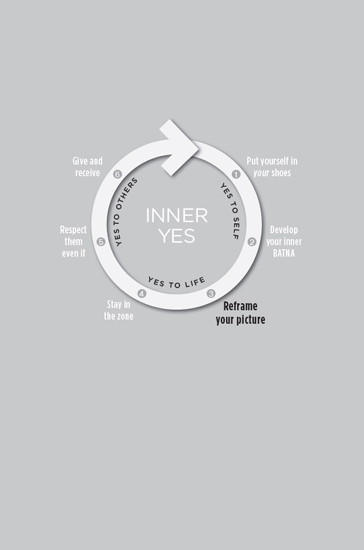

If, like James, we can learn to reframe our picture of life as essentially friendly even in the face of adversity, we will not only be able to get to yes with ourselves but will have a much better chance of getting to yes with others. In reframing your picture of life, three practices can help, in my experience. First, remember your connection to life. Second, remember your power to make your own happiness. Third, learn to appreciate the lessons that life brings you.

“A human being,” Einstein once wrote, “is part of the whole called by us ‘Universe,’ a part limited in time and space. He experiences himself, his thoughts and feelings as something separated from the rest, a kind of optical delusion of his consciousness . . .”

My original training was in anthropology—the study of human nature and culture. As I learned in my studies, the interconnectedness of human beings is an anthropological truth. We are not separate at all, as Einstein points out, but rather inextricably woven into a larger web of human and other living beings. We are intimately connected to the whole biologically, economically, socially, and culturally. We know this truth scientifically, but it is often hard for us to appreciate it fully. We all too easily forget our connection to life.

Sometimes it takes a real shock for us to see through Einstein’s optical delusion. Dr. Jill Bolte Taylor, a Harvard neuroanatomist, suffered a stroke at the age of thirty-seven that flooded and disabled the left hemisphere of her brain. “How many brain scientists have the opportunity to study their own brain from the inside out?” she shared at a celebrated TED talk. “In the course of four hours, I watched my brain completely deteriorate in its ability to process all information. On the morning of the hemorrhage, I could not walk, talk, read, write or recall any of my life.”

At the same time, to her great surprise, Taylor began to feel a sense of euphoric happiness as she shed the stress and anxieties of her life. “Imagine what it would be like to be totally disconnected from your brain chatter,” she told the TED audience. “I felt a sense of peacefulness.” Her sense of separateness—the optical delusion—vanished and she felt connected to life. Without intending it, she had reframed her picture of life from unfriendly to friendly.

It took Taylor eight long years to recover from the stroke. It was slow and difficult, but her desire to teach others about the state of happiness and peace that she had found kept her motivated. Taylor came to understand what had happened to her in terms of the strikingly different functions of the two halves of the brain.

Generally speaking, the left side of our brain is responsible for language, logic, judgment, and a sense of time, the tools we need to navigate our daily lives. “Our left brain thinks linearly, creates and understands language, defines the boundaries of where we begin and where we end, judges what is right and wrong and is a master of details, details and more details about those details . . . It focuses on our differences and specializes in critical judgment of those unlike ourselves . . .” Taylor writes. This is the side of Taylor’s brain that was affected during her stroke.

If the left side of the brain is responsible for our sense that we are separate and different from others, the right side gives us a sense of connection to life and to others. “Our right mind focuses on our similarities, the present moment, inflection of voice, and the bigger picture of how we are all connected. Because it focuses on our similarities . . . [our right brain] is compassionate, expansive, open, and supportive of others,” Taylor writes.

Clearly, we need our left brain to help us navigate in the world and to protect us against life’s dangers. The left brain is essential. But we also need our right brain to feel the kind of connection and contentment that Taylor experienced when she had her stroke. The right brain perspective helps us answer Einstein’s question in the affirmative: life is ultimately on our side.

Dr. Taylor was able to connect fully with the right side of her brain accidentally through a traumatic stroke. Once she found her way to the right brain, she was able to find it again and again. But how about the rest of us? How can we access the sense of connection that comes from the right brain and dissolve the optical delusion of separation that Einstein describes? How can we remember our sense of connection and common ground with others so that it becomes our default way of living? How can we consciously choose to leave behind the chatter of the left brain when it does not serve us?

Taylor believes that each of us can learn to engage the right side of the brain more frequently and easily. One way is to participate in creative and physical activities that exercise the right brain. For Taylor, these activities include waterskiing, playing the guitar, and making stained-glass art. Each of us has our own preferred ways.

One of my favorite activities is climbing mountains, which I have had the pleasure of doing ever since I was a boy of six living in the Swiss Alps. The view from a mountaintop is breathtaking. As I gaze out, with the whole world seemingly stretched out below and the sky above, I get the feeling that I’m dropping away. My body seems to shrink in comparison with the size of the mountains all around. I appear to fade into the background—a tiny dot taking its place on the canvas of the universe, an inseparable part of a bigger picture. The optical delusion dissolves for a moment and I can glimpse with my mind’s eye the scientific truth that all is interconnected. I feel infinitesimal and yet somehow infinite, humbled and uplifted all at once.

We are so used to seeing the world through the lens of our left brain—logical, critical, and full of boundaries—that this “bigger picture,” this sense that everything is interconnected, may seem difficult to grasp. But it is in fact the view we are all born with. Babies in the womb and at their mother’s breast naturally feel connected, having little awareness of where their body ends and their mother’s body begins. As adults, we may catch glimpses of this bigger picture—in moments when we feel deep love or wonder or beauty. We each have an innate ability to connect with the life around us. All we need to do is exercise it.

Because modern life, with all its activities and distractions, conflicts and negotiations, draws far more on our left brain, it helps to have a daily practice to develop our right brain capacity. Every day we can choose to spend some time on our “inner mountaintop”—through a walk in the park, a period of sitting in silence, or a time for meditation or prayer. We can contemplate or create a piece of art, or we can listen to or play a piece of beautiful music. By engaging in such activities, Taylor writes, we are creating neural pathways back to the right side of the brain, which grow stronger every time they are used.

Then, when we happen to face a difficult conversation or negotiation, we may find it easier to access the right brain and remember our sense of connection. I recall a walk I took in Paris just before a momentous business negotiation to seek an end to an acrimonious high-stakes dispute that had cost both parties and their families much personal grief as well as millions of dollars in legal fees. At the end of my walk, by chance, I passed by a new outdoor sculpture exhibit in Place Vendôme. The statues were startling in the bright sunlight: giant silver and golden buddhas from China with great beaming smiles, obviously enjoying life to the utmost. Contemplating these glowing statues suddenly put the heated conflict in perspective and inspired me with a simple phrase to start the negotiation.

An hour later seated at lunch, when my counterpart, a distinguished banker representing the other side, asked me why I had requested the meeting, I responded: “Because life is too short! Life is too short for these mutually destructive conflicts that consume people and their families with stress, tension, and a huge loss of resources.” That simple phrase, which called to mind the bigger connected picture, set a constructive tone for the successful talks that followed.

In negotiation, perhaps the biggest driver of win-lose thinking is a mindset of scarcity. When people feel there isn’t enough to go around, conflicts tend to break out. Whether it is a fight between different department heads in the same sales organization over their slice of the budget or a quarrel between two children over a piece of cake, the game quickly becomes win-lose. In the end, both sides often end up losing. The fight damages the working relationship between the departments so that both fall short in meeting their numbers and, in the midst of the kids’ quarrel, the piece of cake falls on the floor.

In my work as a mediator, I have found that one of the most effective negotiating strategies is to look for creative ways to “expand the pie” before dividing it up. For example, the two departments could explore ways in which, through greater cooperation, they could increase sales and justify an increase in the budget for both. Or the children could find some ice cream to add to the cake so there is more for both. There may be limits to tangible resources, but there are few limits to human creativity. I have observed hundreds of negotiations in which both parties were able to create more value for each other through such creativity.

Yet, as I have noticed, it is not always easy for people to expand the pie. Sometimes, the obstacle lies in the nature of the resource; there just seems to be no way to create more value. But perhaps more often, in my experience, the obstacle lies in our mindset of scarcity, an underlying assumption that there is a “fixed pie” that cannot be expanded. How then can we reframe the picture and change our mindset from scarcity to sufficiency or even abundance? What helps, I find, is to look for ways to expand our “inner pie,” which can then make it easier for us to expand the outer pie.

Harvard psychologist Daniel Gilbert likes to challenge his audiences by asking a question about happiness: “Who is likely to be happier: someone who wins millions of dollars in the lottery or someone who loses both their legs?” Everyone believes the answer is obvious—but it is not. The astonishing answer from the research is that, after a year passes, the lotto winners and the amputees are about as equally happy as they were before the event.

The research suggests that, with a few exceptions, major events or traumas that occur even three months earlier have little to no effect on our present happiness. The reason, Gilbert goes on to explain, is that we are able to make our own happiness. We change the way we see the world so that we can feel better. We are much more resilient than we imagine. “The lesson . . . ,” Gilbert says, “is that our longings and our worries are both to some degree overblown because we have within us the capacity to manufacture the very commodity we are constantly chasing.” As Gilbert’s research suggests, we may think that happiness is something to be pursued outside us, but it is actually something that we make inside.

This conclusion may be hard to believe, particularly because many of us have been taught from early on that happiness and fulfillment come from external conditions such as money, success, or status. Julio, a successful economist, found himself at age twenty-seven having accomplished everything he had wanted. He was a manager at a multinational strategy firm. He was in a good relationship. He had moved to New York City to open up an office and complete his MBA. Julio explains:

From the time I was young, I had this image of what success looked like: two cell phones, working all the time, traveling. And now I had achieved it. But then one day I woke up and felt a sadness and emptiness inside. I felt incomplete. None of what I had achieved made any sense to me. None of it was going to give me the feeling of peace and calm that I wanted.

Julio went in search of what was missing: He slowed down his life a little and took up meditation. He started spending more time with himself and more time in nature. “Eventually I discovered that the peace and calm I wanted was already inside me. I just had to stop and look. And then I noticed that the changes inside me produced changes outside of me,” Julio remarked. “I was less stressed at work, kinder to people, calmer. And people around me noticed. I was a better colleague, a better boss, a better employee.”

Julio discovered that the outer happiness he was pursuing was fleeting and by its very nature scarce. It came, for example, after he achieved a career goal, and then it went away. Only inner contentment, the kind he could make himself, was sufficient and enduring. By taking up activities that stimulated his right brain, like time in nature and meditation, he was able to reframe his view of life, which made him a better person to be around. By getting to yes with himself, Julio found it easier to get to yes with others.

Abraham Lincoln had a point when he reflected a long time ago: “I have come to realize that people are about as happy as they make up their minds to be.” Our ability to meet our deepest needs for happiness and contentment is, in fact, part of our nature. As children we know this instinctively but, as adults, we somehow cover up our essential nature with life’s daily worries and instead hope that others—our spouses, our bosses, our colleagues, our friends—will meet our needs. We often end up in conflicts and difficult negotiations precisely because we believe that only the other person can make us satisfied—typically by relinquishing something he or she has and that we want.

The truth is that, to a much greater degree than we might imagine, we each have the capacity to take care of our own deeper needs for contentment. It is our birthright, a capacity that has been there all the time and that we simply need to reclaim, as Julio did. Each in our own way, we can begin to discover the simple things of life that make us happy. No matter how difficult life may seem at times, it is also capable of providing us what we need most. Life is our ally.

If, as Professor Gilbert’s research suggests, we are capable of manufacturing our own happiness, then the very thing we most want, happiness, is not scarce at all, but sufficient and possibly even abundant. To a great extent, it depends on us. Could it be that we have been going thirsty while perched atop a spring of abundant flowing water?

In my work helping others get to yes, I had long made the conventional assumption that, if I can help people obtain the outer satisfaction of a good agreement, it will provide the inner satisfaction they seek. If only they can get the other person to agree to do what they want, then they will be satisfied and happy. People are naturally disappointed when the other person refuses to say yes or to properly carry out his or her part of the bargain. I have long observed the frustration, anger, sadness, and destructive conflict that ensues and wondered if there is a better way.

Over the years, I have come to realize that my original working assumption was incorrect. The outer satisfaction of a good agreement usually only brings temporary inner satisfaction. True enduring satisfaction starts inside. From inner satisfaction comes outer satisfaction that then feeds back inner satisfaction—and so on in a virtuous circle that begins from within.

The potential benefits for our negotiations and relationships are great. Paradoxically, the less dependent we feel on others to satisfy our needs for happiness, the more mature and truly satisfying our relationships with others are likely to be. The less needy we feel, the less conflict there will be and the easier it will be for us to get to yes in challenging situations.

In my experience, moreover, people who have rediscovered their capacity to create inner satisfaction are far less likely to get trapped in a mindset of scarcity and more likely to use their innate creativity to expand the pie. Here is the point I had missed before: if you want to expand the pie in your negotiations, whether with your spouse or your work partner, your children or your boss, begin by finding ways to expand the pie inside.

As my father-in-law Curt—Opa, as we called him—lay on his deathbed, succumbing to cancer, surrounded by his family, he would oscillate between moments of sheer terror and moments of profound peace. This was a man who, because of his own childhood experiences that included witnessing firsthand the firebombing of Hamburg during World War II, had definitely answered Einstein’s question in the negative. In Opa’s view, the world was an unfriendly place full of scarcity and danger. In a letter he wrote his sixteen-year-old grandson Chris, his principal advice about life was: “Don’t trust anyone.”

One day, however, a few weeks before he died, Opa announced that during the night, he had experienced a deep change in his perspective: “Here,” he declared, “we believe that everything is against us. Now I can see that everything is in our favor.” Although he had not known it, life had always been his ally, teaching him and helping him grow, even through challenging moments. On his deathbed, he had finally come to answer Einstein’s question in the affirmative. Reframing his basic assumptions about life allowed him to finally relax and to let go of his fear and distrust. Instead of resisting the dying process, he was able to embrace it with gratitude for all he had been given in his life. His emotional suffering abated and he died a fulfilled man with his family all around him, loving him.

I used to believe that gratitude for life came from being happy, but I have come to realize that the reverse is also true, perhaps even more so: being happy comes from feeling grateful for life. There may be no better gateway to happiness than cultivating our gratitude. One of the foremost scientific researchers on gratitude, Dr. Robert A. Emmons, reports:

We’ve discovered scientific proof that when people regularly work on cultivating gratitude, they experience a variety of measurable benefits: psychological, physical, and social. In some cases, people have reported that gratitude led to transformative life changes. And even more importantly, the family, friends, partners, and others who surround them consistently report that people who practice gratitude seem measurably happier and are more pleasant to be around. I’ve concluded that gratitude is one of the few attitudes that can measurably change peoples’ lives.

Gratitude for life does not mean denying what is painful, but being able to understand the bigger picture. Once, while I was beginning work on this book, my daughter, Gabi, suddenly experienced sharp pains in her abdomen and was taken to the hospital. She was suffering greatly from nausea and distention. For Gabi, Lizanne, and me, those days were filled with fear, despair, and sadness. At one low point, Lizanne and I were afraid we might be losing our precious daughter. After four days of a worsening state and continuing pain, and with an uncertain diagnosis, the doctors suddenly decided to do a major emergency operation at midnight for a total obstruction of the intestine. As it turned out, the surgery was just in time as the intestine was minutes away from bursting.

Then, gradually over the ensuing days, Gabi slowly recovered and we felt intense relief. During that difficult time, Lizanne, in particular, learned a powerful lesson about acceptance and resilience that gave her renewed confidence in her ability to handle whatever adversities might come her way. She could either lament the unfairness of life or she could practice gratitude—gratitude for Gabi’s life and her recovery and the lessons that came with it. Lizanne chose gratitude.

By feeling grateful for life, we open ourselves to the possibility of experiencing what the Viennese philosopher Ludwig von Wittgenstein called “absolute safety.” Wittgenstein was speaking from his personal experiences serving in the midst of fierce battles during World War I, watching men die by the hundreds and thousands around him. By absolute safety, Wittgenstein meant “the state of mind in which one is inclined to say, ‘I am safe, nothing can injure me whatever happens.’” Absolute safety, he observed, comes from a sense of gratitude and wonder at the very existence of the world. Our bodies remain frail and vulnerable, of course, but the feeling is one of absolute safety. By seeing the universe as essentially friendly even in times of danger, we can help address one of our deepest needs—the need to feel safe.

In Man’s Search for Meaning, Dr. Viktor Frankl tells the story of a young woman, a patient of his, who lay desperately ill in a Nazi concentration camp:

This young woman knew that she would die in the next few days. But when I talked to her she was cheerful in spite of this knowledge. “I am grateful that fate has hit me so hard,” she told me. “In my former life I was spoiled and did not take spiritual accomplishments seriously.” Pointing through the window of the hut, she said, “This tree here is the only friend I have in my loneliness.” Through that window she could see just one branch of a chestnut tree, and on the branch were two blossoms. “I often talk to this tree,” she said to me.

I was startled and didn’t quite know how to take her words. Was she delirious? Did she have occasional hallucinations? Anxiously I asked her if the tree replied. “Yes.” What did it say to her? She answered, “It said to me, ‘I am here—I am here—I am life, eternal life.’”

Here she was in a place of great suffering, about to die, lonely and isolated, away from all family and friends, yet astonishingly, Frankl describes this young woman as “cheerful” and “grateful” for the life lessons her hard fate had brought her. By befriending a tree, actually just a single branch with two blossoms, she found a way to connect with life in the face of imminent death. She was thus able to make her own happiness and relish her last remaining hours. Even in such dire conditions, she was able to answer Einstein’s question in the affirmative and experience the universe as a friend in the form of a tree.

If we can take a lesson from the experience of a young woman whose name we will never know, it might be to remember our astonishing human capacity to reframe the picture: to remember our connection with life, to find happiness even in what may seem like small things, and to appreciate life’s lessons. Life can be extremely challenging at times, but we can choose whether or not to see the challenges as being ultimately in our favor. We can choose to learn from these challenges, even the most difficult ones.

As Frankl made eloquently and poignantly clear in his book, whose original title in German was Saying Yes to Life in Spite of Everything, we have the power to choose our basic attitude toward life, which then directly influences our attitude toward others. Instead of saying no to life, seeing life as unfriendly, we can choose to say yes to life, seeing life as our friend. In making this fundamental choice, we are able to shape our lives, our relationships, and our negotiations for the better.