![]()

He who lives not in time, but in the present, is happy.

—LUDWIG VON WITTGENSTEIN

The pressure was on. At the invitation of the United Nations and the Carter Center, I had been working as a third party in the acute political crisis afflicting Venezuela. Millions of people were on the streets of the capital city, Caracas, calling for the downfall of President Hugo Chavez. Millions of others were on the streets supporting him. People were arming themselves, rumors were circulating about imminent attacks, and international observers were seriously concerned about the possible outbreak of a civil war.

I had received a call from former president Jimmy Carter asking me to meet with President Chavez to discuss how to avert a serious escalation. A meeting was set and I wanted to make the most of this perhaps onetime opportunity to influence the country’s leader. I was preparing the most intelligent advice I could offer. But why, I asked myself, would he even listen to me, a “yanqui professor”?

As was my habit, I went for a walk in the park to seek clarity. I suspected that I would be given only a few minutes with the president, so I was outlining in my head a brief set of recommendations to make. But what occurred to me on the walk was to do the exact opposite of what I had been planning: don’t offer advice, unless of course requested to do so. Just listen, stay focused on the present moment, and look for openings. The risk, of course, was that the meeting would end very soon and I would lose my one chance to influence him with my advice, but I decided to take it.

When the day of the meeting came, tensions were high and protesters were agitating outside the presidential palace. When my colleague Francisco Diez and I arrived, we were asked to wait and then taken to a large ornate receiving room where we were greeted by President Chavez. He invited us to take sofa chairs beside his. I thanked him for the meeting, gave him President Carter’s regards, and asked him about his four-year-old daughter, who was the same age as mine. And I let the conversation unfold naturally.

Soon Chavez was talking freely about his story. He had been a colonel in the military. He had resigned in outrage that he and his troops had been ordered to shoot to kill civilians to quell a riot over food prices in Caracas. He had subsequently launched a coup d’etat and had gone to prison. When released, he ran for president. He talked of his fervent admiration for Simon Bolivar, the liberator of Latin America from Spanish rule in the early 1800s. I listened closely, trying to understand what it was like to be in his shoes.

When he finished his story, he turned to me, and asked, “Okay, Professor Ury, what do you think of the conflict here in Venezuela?”

“Señor Presidente, I have worked as a third party in many civil wars. Once the bloodshed starts, it is very difficult to end. I believe that you have a great opportunity now to prevent a war before it happens.”

“How?” he asked.

“Open up a dialogue with the opposition.”

“Negotiate with them?” He reacted with visible anger. “They are traitors who tried to mount a coup against me and kill me less than a year ago right here in this very room!”

I paused for a moment, going to the balcony. Rather than argue with him, I decided to follow his train of thought.

“I understand. Since you can’t trust them at all, what’s the use of talking with them?”

“Exactly,” he responded.

I was just focused on the present moment, looking for an opening, and a question occurred to me: “Since you don’t trust them, understandably given what happened to you, let me ask you: What action if any could they possibly take tomorrow morning that would send you a credible signal that they were ready to change?”

“Señales? Signals?” he asked as he paused to consider the unexpected question.

I said yes.

“Well, for one, they could stop calling me a mono [monkey] on their TV stations.” He gave a bitter laugh. “And they could stop putting uniformed generals on television calling for the overthrow of the government. That’s treason!”

Within minutes, the president agreed to designate his minister of the interior to work with Francisco and me to develop a list of possible practical actions that each party could take to build trust and de-escalate the crisis. The president asked us to come back to meet with him the very next day to report on our progress. A constructive process for beginning to defuse the grave political crisis had unexpectedly opened up.

As Francisco and I said good-bye to President Chavez, I glanced at my watch. I had lost track of time and a full two and a half hours had passed. I am convinced that, if I had followed my first thought to begin the meeting by reciting my recommendations, the president would have cut the meeting short after a few minutes. After all, he had a long line of people waiting to see him. Instead, because I had deliberately let go of trying to give advice and instead just stayed present and attentive to possible openings, the meeting had become highly productive.

If we want to get to yes in a sensitive situation, the key is to look for the present opportunity, the chance to steer the conversation toward a yes, as happened with President Chavez. In most situations, I find, there is an opening if we are attentive enough to see it. But it is all too easy for us to miss. I have been in so many negotiations where one party signals an opening or even makes a concession and the other party does not notice it. Whether it is a marital argument or a budget disagreement in the office, it is so easy for us to be distracted, to be thinking about the past or worrying about the future. Yet it is only in the present moment when we can intentionally change the direction of the conversation toward an agreement.

I learned this lesson of looking for the present opportunity many years ago from my mentor and colleague Roger Fisher. While the other university professors I knew focused on either understanding the history of a particular conflict or predicting its future, Roger focused on the present opportunity for constructive action. “Who can do what today to move this conflict toward resolution?” was the question he always liked to ask. Roger knew that, as interesting and informative as the past or future might be, the power to transform the conflict lay in the present moment. His focus on the ever-available opportunity to move toward a yes was an eye-opening lesson for me.

But what I did not fully appreciate at that time is the prior step that makes it possible for us to focus on the present opportunity in our interactions with others. If we are to spot the present opportunity, our internal focus naturally needs to be in the present moment. Our best performance comes from being in a state of relaxed alertness, paying attention to the here and now. Research psychologist Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi called this state “flow” in his celebrated book about the psychological state of high performance and inner satisfaction. Athletes sometimes call this state the “zone.” If tennis players, for example, get preoccupied with their last point or the next point, they will not perform well. Being fully present—being in the zone—they can surrender to the moment and play their best. Former sprinter Mark Richardson, talking about his experience of being in the zone as a runner, explains:

It’s a very strange feeling. It’s as if time slows down and you see everything so clearly. You just know that everything about your technique is spot on. It just feels so effortless; it’s almost as if you’re floating across the track. Every muscle, every fiber, every sinew is working in complete harmony and the end product is that you run fantastically well.

Just as it is valuable for tennis players, runners, and other athletes to stay in the zone, so it is for us when we are trying to get to yes with others, whether with a spouse or partner, a work colleague, or a client. As I discovered in my meeting with President Chavez, being fully attentive in the present moment makes us less likely to react, helps us pay attention to possible openings, and accesses our natural creativity so that we can more easily reach mutually satisfying agreements. In addition to its positive effects on our performance, the “zone” is also where we tend to experience the greatest inner satisfaction and enjoyment.

It is not easy at all, however, to stay focused on the present moment. Perhaps the biggest obstacle is an internal resistance or no to life as it is: we regret the past, worry about the future, and reject our present circumstances. The key to staying in the zone is to let go of this internal resistance and accept the past, trust the future, and embrace the present, just as they are. The key, in other words, is to say yes to life.

Relaxing our tight grip on life may be harder than it seems. I am reminded of my adventures as a mountain climber in my teens and twenties. After my friend Dusty and I had climbed up to the very top of a peak, we would descend by rappelling, using a rope to lower ourselves down the precipice. To rappel, we would walk backward off a ledge and then walk down the cliff face, sometimes over a thousand feet high, holding ourselves perpendicular to the surface. At first, it was unnerving and frightening to rappel down; every instinct in my body told me not to let go and let myself fall off the precipice. But if I did not loosen my grip on the rope, I would get stuck, unable to descend the mountain. My desire to control the situation—and fear of what might happen if I didn’t—stood starkly in the way of making any progress and getting what I wanted: to get back down.

Sometimes we don’t really want to let go of our controlling grip on life—just as I didn’t want to let go of the rope when I first learned to rappel. We may believe that worrying incessantly about the future will keep us out of danger. We may enjoy brooding over the past, blaming others because it makes us feel righteous and superior, or more alive through the anger. We may want to control and even fight our present circumstances when they don’t fit our expectations or our plans. As George Bernard Shaw once observed: “People become attached to their burdens sometimes more than the burdens are attached to them.”

For all these reasons, overcoming our resistance to letting go is a slow process. To learn to rappel, I started by relaxing my grip on the rope for a few seconds, feeling that I was safe, and then loosening my grip a little more, followed by holding on again, and so on until eventually I became fully comfortable and accustomed to walking backward off a cliff. Once I did let go of the rope, there was nothing to do except to enjoy the view. We need the same mixture of patience and persistence to meet the challenge of letting go and staying in the zone. After a while, it gets easier until we don’t even give it a moment’s thought.

One time, I remember vividly, Dusty and I had to rappel down from a high alpine peak in a storm with pouring rain whipping into our faces amid distant claps of thunder and occasional flashes of lightning. We found ourselves on a small rock ledge and the only thing that seemed available to serve as an anchor for the rope was a small slender pine tree clinging to the cliff. In a hurry, we wrapped the rope around the tree, tugged on the tree to test it, and proceeded.

As I began to lower myself over the lip of the high precipice and entrusted my full weight to the rope, the pine tree shivered and then—as if in slow motion—came uprooted. I grasped for the edge of the ledge and caught myself just in time. Dusty and I looked at each other, speechless, shocked by what might have happened. We stopped, looked around with some diligence, and finally found a more reliable anchor, a boulder. This time we were able to rappel safely down the mountain. Needless to say, Dusty and I learned to appreciate keenly the value of anchoring ourselves to something solid before letting go.

I find that the same lesson holds true for letting go of our tight grip on life. Our ability to relax and let life flow naturally depends on how solidly anchored we feel in a friendly world. If we can reframe our picture of life and find satisfaction from within, then we will be more willing to let go of our resentments about the past and our anxieties about the future. Reframing allows us to relax and to accept life just as it is.

“When I think of what Craig has done to me, I feel furious,” said one client of mine enmeshed in a business dispute to me during a moment of candor. “So it gives me pleasure to attack him. If I settle our dispute, what will my life be like without my private war?” He was so focused on the past and on the pleasure of revenge that he had lost sight of his true objectives in the negotiation and in life.

As a mediator in family feuds, labor strikes, and civil wars, I have witnessed the heavy shadow of the past and how it can create bitterness, resentment, and hatred. I have listened for days to blame and recriminations and who did what to whom. I have observed how easily the human mind gets bogged down in the past and forgets the present opportunity to end the conflict and the suffering.

Holding on to the past is not only self-destructive because it distracts us from reaching a mutually satisfying agreement, but it also takes away our joy and even harms our health. And it affects those around us who are our biggest supporters in life. Watching us hold on to the past and poison our present takes away their joy and well-being. It is a loss for everyone. If we truly realized how much it costs us to hold on to the past, how self-destructive it ultimately is, we might not wait so long to let go.

In the dispute above, once my client was able to let go of his temptation to dwell on the past and to settle his differences with his adversary, he told me he was a different man, feeling much lighter. Even his young children had noticed—and probably worried about—how much their father had been consumed by the conflict. When it ended, they saw, clearly relieved, a noticeable change in their father: “Daddy is not on the cell phone all the time,” they told their mother.

Letting go of the past can be truly liberating. In a speech at the UN, former U.S. president Bill Clinton recalled a question he once asked Nelson Mandela: “Tell me the truth: when you were walking down the road that last time [as Mandela was released from prison], didn’t you hate them?” Mandela replied: “I did. I am old enough to tell the truth. I felt hatred and fear but I said to myself, if you hate them when you get in that car, you will still be their prisoner. I wanted to be free and so I let it go.”

Here was a man who had spent twenty-seven years in prison and had every reason to be bitter and angry. The great and unexpected gift he gave to his compatriots was to help them let go of the heavy burden of the past so that they could get to yes and begin to build a free South Africa for all. By learning to accept and forgive his former jailers, Mandela inspired thousands of others to forgive too. One was a young fellow prisoner at Robben Island, Vusumzi Mcongo, who had been severely tortured in detention for his role in leading a student boycott. “We cannot live with broken hearts,” Mcongo said. “In time we have to accept that these things have happened to us, that those years have been wasted. To stay with the past will only bring you into turmoil.”

Forgiving those who have wronged us does not mean condoning or forgetting what they did. It means accepting what happened and freeing ourselves from its weight. The first beneficiary of forgiveness, after all, is ourselves. Resentment and anger tend to consume us and hurt us perhaps much more even than they hurt the other. Holding on to old resentments makes about as much sense as carrying our bags while traveling on a train; it only tires us out needlessly.

As important as it is to forgive others, perhaps the most important person to forgive is oneself. Without doubt, at some point each of us has felt regret, guilt, shame, self-hatred, and self-blame for all the ways in which we have broken promises to ourselves and hurt ourselves as well as others. These feelings naturally tend to fester and take our attention away from the present moment. That’s why the poet Maya Angelou urged that forgiving ourselves is crucial:

If you live, you will make mistakes—it is inevitable. But once you do and you see the mistake, then you forgive yourself . . . If we all hold on to the mistake, we can’t see our own glory in the mirror because we have the mistake between our faces and the mirror.

Accepting the past is not only about letting go of accusations toward others and ourselves; it’s also about accepting the experiences life has given us, however challenging these might be. If we don’t let go of our resentment and regret, we become prisoners of the past. To accept our past, it helps to reframe our stories and give a positive meaning to even the most difficult life events. We may have no power to change the past, but we do have the power to change the meaning we assign to it.

If I did not believe before in the power of reframing our stories, certainly the experience with my daughter Gabi’s medical challenges has persuaded me of it. In the early years after Gabi’s birth, my wife, Lizanne, told me she felt she was in a dark tunnel out of which she would never emerge. But over time she and I learned to paint a different picture of the experience. The truth was that, as painful and difficult as it was to watch our daughter undergo medical procedure after medical procedure, it challenged Lizanne and me to grow as human beings and to draw on our inner resources. We can only be grateful for the valuable life lessons Gabi’s journey brought to us—lessons reflected in this book. I personally deepened my ability to observe my thoughts and feelings, to put myself in my shoes, to see life as an ally and friend. Looking back, Lizanne and I have come to appreciate the entire experience as a “blessed shock,” one that paradoxically woke us up to life’s potential for experiencing joy in the present. While we would not have voluntarily chosen this path, I can say without a doubt that each of us is happier and more fulfilled today because of all we learned as a result. In fact, I do not believe I would be writing this book were it not for these experiences.

Once when I was speaking to a group of businesspeople about the critical importance of developing your BATNA—your Best Alternative To a Negotiated Agreement—a man came up to me and said, “Yes, that’s true. But I also like to think about my WATNA—my Worst Alternative To a Negotiated Agreement.”

“Why is that?” I asked, my curiosity piqued.

“Because I worry a lot about what’s going to happen if things go wrong in the negotiation,” he replied. “It helps me to think about the worst thing that could happen because then I can say to myself: ‘If they’re not going to kill me, then I will probably survive.’ And I laugh it off.”

There is a lot of truth in that man’s comment. We do tend to worry a lot in negotiation and in life, in general, about all the bad things that could happen. While keeping an eye on the future can be useful, worrying about it continually only takes us away from the present moment so that we no longer operate at our best.

I am well acquainted with fear from my work in dangerous conflicts. I have often watched fear take hold of me and of others. But what I’ve learned over the years is that the vast majority of our fears are baseless. As the French philosopher Michel de Montaigne noted four centuries ago: “My life has been full of terrible misfortunes most of which never happened.” In the end, fear ends up doing more damage to us than the very danger it imagines. “He who fears he shall suffer,” Montaigne concluded, “already suffers what he fears.”

The alternative to fear is trust. By trust, I don’t mean the belief that there will be no challenges or painful experiences. Rather, I mean the confidence that you will be able to deal with the challenges that come your way. That trust is what enabled me to have the productive conversation with President Chavez described at the beginning of this chapter. If I had listened to my fear of failure, I would never have let the conversation flow naturally into what became a real opening in the negotiation.

Trust is not a onetime shift in attitude, but rather a conscious choice we face many times a day. In every interaction with others, a client or a boss, a spouse or partner, we can choose between fear and trust. Will we obey the no voice that counsels us not to look foolish or ridiculous? Or will we listen to the yes voice that encourages us to take a chance and follow our intuition?

Winston Churchill once quipped, “The pessimist sees the difficulty in every opportunity. The optimist sees the opportunity in every difficulty.” He went on to say, “I am an optimist. It does not seem much use being anything else.” Trust in the future, as he knew well from the horrors of war, does not mean ignoring life’s problems. On the contrary, trust is an attitude with which we can actively deal with our problems. Why not try out this attitude and see if trusting—that you can handle whatever life brings you—works better for you than continually worrying about the future?

A number of practical methods can help us let go of our fear of the future. You can observe the fear when it shows up and then consciously release it, shaking it off a bit like a dog shakes off the water after plunging into a lake. You can take a deep breath or two, bringing oxygen into your brain so you can see things more clearly. Or like the businessman I cited earlier, you can also ask yourself a simple but powerful reality-testing question when you are anxious about a particular future outcome: What is the worst thing that can happen here? By facing your fears from a place of clarity, you’ll be better able to relax and to stay in the zone. Our bodies do not distinguish between real threats and imagined threats as they gear up for fight or flight, so in the great majority of situations, a little bit of perspective can go a long way in helping us let go of fear.

In the end, perhaps the surest way to free yourself from unnecessary fears is to remember your inner BATNA and your yes to life. Your commitment to take care of your needs and your confidence that life is on your side will give you a sense that, no matter what happens in the future, everything will be okay in the end.

An old Chinese proverb counsels: “That the birds of worry and care fly over your head, this you cannot change, but that they build nests in your hair, this you can prevent.”

Once we release ourselves from the burden of the past and from the shadow of the future, then we are freer to live and act in the present. We can visit the past from time to time to learn from it and we can visit the future to plan and take necessary precautions, but we make our home in the only place where we can make positive change happen: in the present moment. It is by being present and spotting the present opportunities in our negotiations that we can most easily get to yes with others.

It is all too easy in today’s world of cell phones, texts, and e-mail to get distracted from the present moment. Underlying our tendency to distract ourselves is a resistance to the way that life is for us right now. We tend to have idealized expectations of how life should or should not be, and our inner judge is constantly comparing our reality to that expectation. We keep score. “I should have made the sale by now.” “I should not have just spoken that way to my boss.” “My spouse should be nicer to me.” A telltale sign of expectations are the words should and should not.

Accepting life as it is does not mean resigning ourselves to the way things are. In fact, constructive change starts from accepting reality regardless of how painful it might be—not from losing time and energy resisting it. My friend Judith had a very difficult time when her son Ben went through a phase of rebellion that had started when he was nine and reached a peak of intensity when he was thirteen. Ben would repeatedly—and harshly—reject her and her attempts to connect with him. Judith was on a roller coaster of hurt and anger, helplessness and determination, grief and tears. She felt as though she was falling apart.

“I would not let go. I felt like I was fighting for my life and for that of my son,” Judith explained. “My husband was running up and down the stairs to the basement family room where Ben had moved, like a frantic mediator attempting to carry messages between the rebel forces and the crumbling government.”

Judith was expressing a loud no to Ben’s behavior, essentially a no to life as it showed up in the present moment. No matter how much she struggled and resisted, however, she was unable to force Ben to accept her at that point. It is not easy to let go of trying to control life, particularly when the stakes seem high.

Behind our fear of letting go may be the false assumption that if we don’t control all the circumstances around us, then everything will fall apart and our lives will be destroyed. Our instinct is to protect our idealized version of how life ought to be. The irony, of course, is that resisting our present reality is destructive not only to us, but also to those around us. In Judith’s case, her relationship with her husband was severely strained by their mutual judgment, blame, hurt, and helplessness.

So how do we, in fact, let go?

Judith learned to let go by testing her assumptions about the future, which motivated much of her need to control her relationship with her son. One day, while walking on the trail behind her home, she asked herself: What is the worst thing that could happen here? “Other than my child dying,” Judith realized, “the worst thing I could imagine was that I would end up having active relationships with only two of my three children.” In negotiation terms, she was asking herself a reality-testing question, a question about her best alternative if she was not able to get to yes with her son.

Suddenly Judith’s situation didn’t seem so dire. She asked herself: Can I live with this? Can I be happy even if I never have a good relationship with my son? And the answer was clear—she could. “It wasn’t what I wanted,” Judith clarifies, “but I could live with it. I still had the capacity to find joy and satisfaction in my life. My well-being was not dependent on this child’s love or approval.” In that brief moment, Judith felt liberated from the tyranny of her fears.

“Gradually, I let go,” Judith explains. “I let go of needing his acknowledgment, of needing him to love me or even needing him to like me. I let go of needing him to call or talk to me. I let go of needing him to feel the same way about me as he did about his father. And ultimately, I let go of needing any relationship with him at all. As I faced my life as it was, rather than life as I had hoped it would be, my pictures of myself as a mother, a wife, of being anyone I had previously thought I was, fell away. In place of this came freedom.”

Once Judith was able to let go of her expectations of how life should be, then paradoxically healthy change unfolded—naturally. Letting go turned out to be the unexpected key to transforming the conflict between mother and son, a relationship that healed slowly over the years. Precisely because Judith was able to let go of her neediness and accept her son just as he was, he was able after some time to come closer to her, apologize for hurting her, and tell her how much he loved her. By choosing to face life as it was, by getting to yes with herself, she was able to get to yes with her son as well as with her husband.

As Judith’s case shows, it is hard to get to a mutually acceptable solution to a conflict if we have not first accepted the situation as it is. Accepting the present, I have learned, means accepting a gift from life. The present moment, as much as we might feel aversion to it—as Judith felt aversion to her contentious relationship with her son—is indeed a present. We might imagine that we were supposed to get another gift, but the present is what it is.

In this matter, perhaps my greatest teacher is my daughter, Gabi. Here she is, having undergone fourteen major surgeries, yet she doesn’t lose any time looking back with resentment or regret or feeling sorry for herself. She shakes it off. She has a zest for life and finds enjoyment and excitement every day. If I find my mind wandering to her past or worrying about her future, I simply remember her laser-like focus on the present—and I let go. If she can relax and stay in the zone, then I can do the same.

As Lizanne and I learned from watching Gabi go through so many surgeries, pain happens. It is part of life. But when we resist life and its pain, we start to suffer. As the saying goes, pain may be inevitable but suffering is optional. We may think that it is the suffering that causes us to resist, but paradoxically it is the resistance that causes us to suffer. We get trapped in disappointment and endless wishing that this was not happening to us. Resisting our current circumstances often prolongs the misery, sometimes indefinitely. It is not easy, of course, but we can choose to limit our suffering through gradually learning to let go of our no—our resistance—and saying yes—learning to accept life as it is.

If there is a single lesson I have learned, it is this: in life, we are destined to lose many things. That is the nature of life. Never mind. Just don’t lose the present. Nothing is worth it. There is nothing more important than “this,” the fullness of life right now.

A key to staying in the present moment, I have learned, is to be able to focus on what lasts while accepting what passes. It is to stay anchored in our essential connection to life while we say yes to situations that pass us by—some good, some painful. Let the passing pass, let the lasting last. By focusing on what is lasting—life itself, nature, the universe—we become more aware of what is passing, more appreciative of the preciousness and temporary nature of every experience. In turn, as we become more aware that these experiences won’t last forever, we become less reactive in situations of conflict—after all, whatever the conflict is, this too shall pass—and we find it easier to look for the present opportunity to get to yes with others.

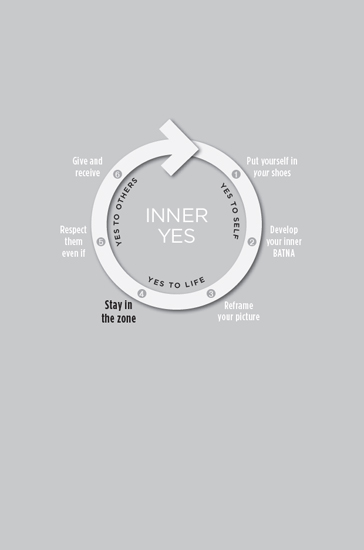

If the first step in saying yes to life is to reframe our picture of life as friendly, the second step is to stay in the zone—a place of high performance and satisfaction. Accepting life means saying yes to the past, letting go of lingering resentments and grievances. It means saying yes to the future, letting go of needless worries and replacing fear with trust. And it means saying yes to the present, letting go of our expectations and appreciating what we have in the moment. It is not always easy, of course. It takes strength to forgive the past, courage to trust the future, and disciplined focus to stay present in the midst of life’s constant problems and distractions. But, however great the challenge, the rewards of inner contentment, satisfying agreements, and healthy relationships are much greater.

Having examined our attitude toward life, it is time to examine our attitude toward others. Saying yes to life prepares us for the next challenge, which is to say yes to others.