![]()

This is the true joy in life, the being used for a purpose

recognized by yourself as a mighty one . . . I am of the

opinion that my life belongs to the whole community, and as

long as I live it is my privilege to do for it whatever I can.

—GEORGE BERNARD SHAW, MAN AND SUPERMAN

As challenging as it can often be to find win-win solutions in our negotiations and relationships, I believe that the process of getting to yes with ourselves allows us—and indeed asks us—to aim for an even more audacious goal. It invites us to pursue “win-win-win” outcomes, victories not just for us and the other side, but also for the larger whole—the family, the workplace, the nation, and even the world. In a divorce, as spouses struggle with each other, how can the needs of the children be met? In a dispute between union and management, how can the organization stay financially healthy to provide good jobs for everyone and their families? In a conflict between two ethnic groups, how will people stay safe?

The key to finding win-win-win solutions that serve everyone is to be able to change the game from taking to giving. By taking, I mean claiming value only for yourself, whereas by giving I mean creating value for others, not just yourself. If taking is essentially a no to others, giving is a yes. Giving lies at the heart of cooperation. It is a behavior but it originates inside of us as a basic attitude toward others. Most of us adopt an attitude of giving in certain settings, as when we are with our family, friends, and close colleagues. But how can we cultivate an attitude of giving and cooperation with those who are not so close to us or even with those who may be in conflict with us? That is the challenge.

In many years of teaching win-win negotiation methods, I have watched again and again people learn cooperative negotiation techniques only to revert to win-lose behavior the moment they face a real conflict. In the heat of an argument, when emotions are running high, the fear of scarcity often wins out. We are afraid that, if we cooperate, there will not be enough to meet our needs or the other side will take advantage of us.

It is so tempting, particularly in conflicts, to focus just on claiming value for ourselves rather than creating value for others as well as ourselves. As difficult, however, as others can sometimes be, the opportunity to change the game to win-win-win lies in our hands. We can lead the way by examining and shifting our own attitude.

Whatever the perceived challenges, there are enormous benefits in adopting a basic attitude of giving for our negotiations as well as our lives. In his groundbreaking book Give and Take, professor Adam Grant of Wharton Business School presents an impressive array of evidence from academic studies that the most successful people in life, perhaps surprisingly, are “givers,” not “takers.” It is, of course, important to be intelligent in one’s giving and mindful of those who merely take, otherwise you may end up doing yourself a disservice. But the research on the tangible benefits of giving is eye-opening.

One study, for example, carried out by Grant concludes that salespeople who focus on giving genuine service to customers earn more than those who are in it primarily for the money. Another study showed that people who give away more money to charity tend to be happier and end up, on average, earning more. The research suggests that giving works in part because it increases the probability that someone else will do something good for you. Giving, it turns out, is the path to personal satisfaction, both inner and outer.

So how can we strengthen our attitude of giving in our dealings with others? It is worth noting that all the prior steps of getting to yes with yourself lead up to this point. If we feel a sense of satisfaction and sufficiency from within, then it is easier to give to others around us, even when they are difficult. Having addressed our deepest needs, it is easier to address the needs of others. And by giving others our respect, we have already, in a sense, adopted an attitude of giving.

Still, the fear of scarcity can be very strong. To cultivate a basic attitude of giving, it helps to root that attitude in our self-interest, in our pleasure, and in our purpose. In other words, give for mutual gain, give for joy and meaning, and give what you are here to give.

The well-known Chinese billionaire Li Ka-Shing, who began his life in arduous and poor circumstances and went on to become one of the wealthiest men in the world, was once asked by a magazine interviewer about the secrets to his business success. One key, he said, was that he always treated his partners fairly and, in fact, gave them a little more than he took for himself. Everyone wanted to be partners with him and it was his partners who helped him to become wealthy.

The first way to strengthen our attitude of giving is to appreciate how creating value for others can help us tangibly meet our needs. Giving need not mean sacrificing our interests. It does not require us to become a Mother Teresa or Mahatma Gandhi. Nor does giving mean giving in to the other person’s demands. Giving does not mean losing. Giving in the first instance can simply mean looking for mutual gain, helping others at the same time as we help ourselves. That is the essence of win-win negotiation.

The most successful negotiators I know tend to be people who focus on addressing the interests and needs of their counterparts at the same time as looking after their own needs. In doing so, they find ways to create value and expand the pie for both sides and end up generally with better agreements than people who just try to claim as much as possible for themselves at the expense of others. Solid research supports this approach. In a comprehensive analysis of twenty-eight different studies of negotiation simulations, led by Dutch psychologist Carsten De Dreu, the most successful negotiators turn out to be people who adopt a cooperative approach that focuses on meeting the needs of both parties.

In dealing with any conflict or negotiation, we have four possible choices, depending on the concern we show for our interests and the other side’s. We can choose a hard adversarial win-lose approach, in which we are concerned about our interests alone. We can choose a soft accommodating approach, in which we show concern only for the other side’s interests and not ours. We can choose an avoidance approach in which we don’t talk about the issue at all, thereby not showing much concern for either the other person’s interests or ours. Or we can choose a win-win approach, in which we show concern for both the other person’s interests and ours.

Much of my work in teaching negotiations and advising parties in conflict has been helping people find their way from an adversarial win-lose approach to a win-win approach. People often learn the hard way by first arriving at an outcome where everyone loses. While an adversarial approach may prove costly and ineffective, a soft accommodating approach typically does not work much better. If we give everything away to please the customers, we may not be in business long enough to serve the customer. If, in taking care of an elderly parent, we wear ourselves out in endless sacrifice, we may burn out and not be available to help at all. Avoidance, the third approach, also has pitfalls: if no one talks about the conflict, it often just gets worse. In the end, creating value for both sides usually produces the best and most sustainable agreements and relationships.

In his book, Adam Grant cites the example of Derek Sorenson, a top-class athlete turned professional negotiator for a leading sports team in charge of negotiating contracts for new players. In one such negotiation, he sat down with the agent of a highly promising young player. Sorenson made a low offer, taking a win-lose approach and acting like a “taker.” The agent expressed his frustration repeatedly, pointing out how comparable players were earning significantly higher salaries. But Sorenson would not budge and eventually the agent gave in. Even if it was a loss for the player and the agent, it seemed like a win for Sorenson, saving his team thousands of dollars.

But at home that night, Sorenson had an uneasy feeling. “I could just feel through the conversation that he [the agent] was pretty upset. He brought up a couple points on comparable players, and in the heat of things, I probably wasn’t listening too much. He was going away with a bad taste in his mouth.” Sorenson recognized the potential toll of his win-lose approach on the relationship as well as on his reputation. So he went back to the agent and met his original request, giving thousands of additional dollars to the player. As Sorenson saw it, he was building goodwill. “The agent was extremely appreciative. When the player came up for free agency, the agent gave me a call. Looking back on it now, I’m really glad I did it. It definitely improved our relationship, and helped out our organization.” When we start to appreciate how giving for mutual gain helps us, as Sorenson did, we are motivated as he was to change our attitude from taking to giving.

It also helps that the benefits of giving go well beyond material self-interest.

When I teach negotiation, I often use an ancient fable from Aesop. It is the tale of the North Wind and the Sun, who one day started arguing about which one was more powerful. Was the North Wind more powerful or was it the Sun? Unable to resolve the dispute by argument, they decided to put the matter to a test. From on high in the sky, they looked down on the earth and spied a passing shepherd boy. The North Wind and the Sun decided that whoever could pluck the cloak off the shepherd boy’s shoulders would be deemed the more powerful one.

So the North Wind went first. He blew and blew and blew as hard as he could, trying to rip off the boy’s cloak. But the harder he blew, the more tightly the boy wrapped his cloak around his body and refused to let go. Finally, after a long while, the North Wind took a pause for breath. Then it was the Sun’s turn. The Sun just shone, as it does naturally, and bathed the boy in her warmth. The boy loved it and finally said to himself, What a beautiful day! I think I will lie down for a moment in this grassy meadow and just enjoy the sun. As he prepared to lie down, he took off his cloak and spread it out as a blanket. So the Sun prevailed in her argument with the North Wind.

I find that this old fable has a lot to teach us about the value of giving. If the North Wind’s attitude was to take, the Sun’s attitude was to give. The nature of the Sun is to shine. It does not matter whether a person is rich or poor, kind or mean—the Sun shines on everyone. Its natural approach is win-win-win. And as the fable suggests, the Sun’s approach is more powerful and more satisfying than the approach of the North Wind.

To cultivate our attitude of giving, it helps to discover the sheer joy that can come from giving. Much like the sun shines because that is what it does, not because it expects something back, we can discover the pleasure that comes from giving naturally without thinking about receiving a direct or immediate tangible return. Paradoxically perhaps, giving simply for the pleasure of giving can bring us the most satisfaction in the end.

I will never forget a life lesson I learned from a little five-year-old girl named Haley, the granddaughter of good friends, who had fallen gravely ill with leukemia. Lizanne and Gabi, then three years old, went to visit her at Children’s Hospital when Gabi was there for one of her innumerable medical appointments. They found Haley in extreme discomfort, her face swollen almost beyond recognition, her hair gone, lying wanly on the bed. Seeing Gabi, Haley turned to her mother and whispered in her ear. Her mother excused herself for a moment, went downstairs to the hospital gift shop, and came back to the room with a large stuffed letter G for Gabi.

It wasn’t just Gabi’s face that lit up but it was Haley’s. She knew, early on, the pleasure of making another child smile. Even in her terrible condition, on the verge of dying, she was able to feel the joy of giving for giving’s sake.

When we discover the joy of giving, we give because we feel moved to give. In the first stage of giving, we may give to others simply in order to receive. We may treat the relationship with the other person like a business transaction. In the second stage of giving, however, we give without expecting a direct tangible return.

“My default is to give,” says Sherryann, a manager interviewed by Adam Grant who spends many hours a week mentoring junior colleagues at her firm, spearheading a women’s leadership initiative, and overseeing a charitable fund-raising project at the firm. “I’m not looking for quid pro quo; I’m looking to make a difference and have an impact, and I focus on the people who can benefit from my help the most.”

When we find our motivation for giving in meaning and pleasure, the more we give, the better we feel. And the better we feel, the more we tend to give. Of course, we have to make sure we take care of our needs too, or we will end up feeling used and burned out. There are limits we need to respect, even to giving for pleasure and meaning.

Giving for the pleasure of giving is very different from giving out of obligation. When we feel obliged to give, we rarely feel much pleasure and we often end up feeling unhappy. Consider Scott Harrison’s story. Scott had been raised in a household where he was expected to be unselfish and give, but he was never offered a choice. Like many of us, he wore a mask of altruism to gain his parents’ and his church community’s approval. But in his late teens and twenties, he rebelled against what he saw as hypocrisy and took off his mask. He focused only on pleasing himself with little or no concern for others, making his living promoting nightclubs and fashion events in New York City.

At age twenty-eight, he had all the appearance of success and happiness: lots of money, a Rolex watch, a leased BMW, a girlfriend who worked as a model. Then one New Year’s Eve in Punta del Este, Uruguay, where he had rented a huge house, with horses and servants and $1,000 worth of fireworks to blow up in ten minutes, it suddenly hit him.

I really saw what I had become. Every single thing that I had as a value I had walked away from in this slow burn over ten years. . . . I was emotionally bankrupt, I was spiritually bankrupt, I was morally bankrupt. I looked around me and nobody else was happy either. It was almost as if the veil had been lifted. There would never be enough girls, there would never be enough money, there would never be enough status.

Scott’s crisis provoked an intense period of questioning and soul-searching. He asked himself a couple of powerful and disturbing questions: “What would the opposite of my life look like? What if I actually served others?” Having had the experience of false altruism, he was now interested only in the real thing.

After a few months of spending time with himself alone, reading and probing deeply into his own psyche, Scott decided to volunteer as a photojournalist on a medical hospital ship in West Africa, where he served for two years. Moved and inspired by the suffering and courage he had witnessed, he returned home to found an organization called charity: water, a charity that raises funds to build wells and provide clean water to hundreds of thousands of impoverished people around the world. Today, his deep need for meaning is being fulfilled. Having spent some time with him, I can attest to his energy and enthusiasm. Describing the joy of watching people drink clean water from the wells he has helped fund, he exclaims, “I am on fire.”

Our consumer society has led us to believe that having “things”—material possessions as well as power and success—brings us inner satisfaction. But Scott’s story illustrates the truth that, no matter how much we may get, there is never enough. Our neediness can never be satisfied if we meet only our needs.

In contrast, giving that is genuine and freely chosen can bring us enduring inner satisfaction, precisely because it meets our deepest need to be useful and connected to others, because it allows us to make a difference in the world of others, and because it just makes us feel good. Paradoxically, it is by giving that we often receive what we most want. When we discover giving for pleasure and meaning, a virtuous circle of giving and receiving begins. But receiving does not become the goal of our giving. We give simply because it is who we are and what we like to do. And by giving in this way, as Scott’s story suggests, we create a win not just for ourselves and others, but also for the larger whole.

Perhaps the most enduring way to strengthen our attitude of giving is to find a purpose or activity that makes us a natural giver. Just like a muscle, the attitude of giving benefits from exercise. Through a purpose, giving can become engrained in the fabric of our lives.

A purpose is the answer to the questions Why do we get up in the morning? What makes us excited? What inspires us? For some, a purpose may be to raise and care for a family; for others, it might be to play music or create art. For some, it may be to build something that has never been built; for others, it might be to care for a garden. For some, it may be to give service to customers or to mentor younger colleagues; and for still others, it may be to help people who are suffering. If we can discover a purpose that makes us come alive, it can be not only a source of inner satisfaction but also an excuse to give to others around us and to strengthen the giver in us.

Throughout this book, I have shared the story of my daughter’s medical challenges. Just as I was concluding the writing, something remarkable happened for her that illustrated the benefits of finding a purpose. One morning, Gabi announced to Lizanne and me that she intended to celebrate her sixteenth birthday, which was four months away, by breaking a Guinness World Record. It had long been a dream of hers and a few years earlier, she had tried for the longest hopscotch course and then for the most socks on one foot. This time she said she wanted to attempt the longest-held abdominal plank, a core-strengthening exercise that involves keeping your body absolutely straight in a horizontal position as you prop yourself up on your forearms and toes.

As I’ve mentioned earlier, Gabi was born with a medical condition that has required fourteen major surgeries on her spine, her spinal cord, her organs, and her feet in the course of her life. While trying out for the school volleyball team a few months earlier, Gabi’s coach had asked her to do the plank while the other girls ran, which Gabi has difficulty doing. The coach was astonished to find Gabi still holding the plank position twelve minutes later when the other girls had returned. Seeing the coach’s surprise, Gabi immediately thought, Whoo, Guinness World Record! She wrote to Guinness and learned that the official record for women was forty minutes. Gabi then waited two months until after another major surgery to begin her training.

Lizanne and I were surprised, yet not really surprised, to find out about Gabi’s project. Despite all the adversities in her life, we have never seen her feel sorry for herself. She never falls into the trap of powerless victimhood. We have always marveled at her zest and enthusiasm for life, her ability to take each day and make it fun for herself. We have been astonished at her ability to pick up her life after each surgery, seeing life as essentially on her side. She seems to naturally live in the present, not losing time in regrets about the past or worries about the future. Throughout her childhood, Gabi never lost her underlying yes to self and her exuberant yes to life.

Lizanne and I were supportive of Gabi’s dream and encouraged her to go for it. Weeks went by as Gabi trained to beat the record. In her informal attempts, she went from twenty minutes to twenty-five, to thirty, and once, when her mother was distracting her by asking her questions, she made it past forty minutes. Gabi shared in an interview:

Originally I thought I was going to break the record for me because that’s something I always wanted to do. But the idea came up that I could do this for a cause. And I really liked that idea, especially when I figured out that I could do it for Children’s Hospital. They helped me not only walk and run, but do something extraordinary. I wanted to help them so other kids like me could have a better experience. I wanted to raise money and awareness so the plank could be something much more than a record.

Gabi’s original purpose extended naturally from giving to herself to giving to others as well.

Then, one week before the scheduled attempt, Gabi received an e-mail from the current world record-holder, Eva Bulzomi, alerting Gabi that she had just smashed her own record by an incredible twenty-five minutes. Her new time was 1 hour, 5 minutes, 18 seconds. Guinness had not certified it yet, but it was in process. Lizanne asked Gabi, “Wow, how do you feel about it?”

“This makes it a little harder,” Gabi replied in her low-key manner, undaunted and as determined as ever.

Finally the big day arrived. Gabi’s friends and family gathered around to watch her make the attempt. After holding the plank position for thirty-five minutes, about halfway toward her goal, she hit a wall of discomfort and pain in her arms and tears began to fall on the mat. Gabi’s friends began to sing and entertain her in order to distract her from her pain. As the minutes went by, friends and family started to cheer and to drop down to the floor to do the plank themselves. Finally, at an hour and twenty minutes, Gabi stopped. She had doubled the existing world record. I felt awe and relief as I helped her carefully out of the plank position.

A week later, Gabi appeared on Good Morning America, where an official from the Guinness Book of World Records presented her with the official award. The news went around the world on social media as the video of her breaking the record was seen in over a hundred and fifty countries. She not only inspired thousands of people to test their own limits and turn their own perceived weaknesses into strengths, but in the process she raised over fifty-eight thousand dollars for Children’s Hospital Colorado, more than eleven times her target.

Gabi was remarkably successful in getting what she wanted and, at the same time, benefiting others, many in ways we will never know. She didn’t start her planking project with the purpose of giving to others but she ended there. She learned to appreciate the joy of giving and receiving. As Gabi discovered, nothing strengthens the attitude of giving more than rooting it in a purpose.

Giving what we are here to give, as Gabi’s story shows, may be the greatest sustained source of satisfaction life affords us. But when we give from a sense of purpose, it does not need to be grand. I think of my friend Paola, who studied law and became a lawyer. She had a prestigious career but was not happy. Then she remembered that, when she was a child, she used to love to mix hair conditioners and put her lotions on her dog. It seemed random, at first, but it was a clue to what she loved. Mixing hair conditioners for her dog, she used to imagine herself as a chemist mixing potions that would help humanity. So, mustering her courage and using her savings, Paola left the practice of law and set about establishing a business to make natural soaps and help people in that way. This new way of making a living may not have fit her idealized image of a “successful” career, but it brought her happiness because she had found a way to contribute by doing something she genuinely loved.

Our gifts may seem small but often make a significant difference in the lives of others: taking care of a friend’s child or of an elderly parent in need, helping a neighbor with a daunting home repair, pitching in at work when a colleague gets sick, or simply offering a gesture of kindness to a stranger in the street. The apparent magnitude of the gift does not matter; what counts is giving in an openhearted way.

Perhaps the greatest obstacle in the way of us giving our gifts is the fear, not of our smallness but of our greatness. We are afraid not of our limitations but of our talents. The humanistic psychologist Abraham Maslow used the term “Jonah complex” to describe the fear that prevents us from exercising our talents and fulfilling our destiny. The biblical Jonah sought to run away from his fate, which was the call from God to warn the people of the city of Nineveh to leave their violent and wicked ways or be destroyed. Hearing the call, Jonah heads in the exact opposite direction. While crossing the sea on a ship, a great storm threatens the lives of everyone on board. Jonah somehow knows he is responsible and tells the crew to throw him overboard, which immediately brings the storm to an end. Jonah ends up in the belly of a whale and, only after realizing his mistake in resisting his destiny, is released by the whale onto dry land. Jonah travels to Nineveh and carries the warning in time for people to change their ways and be spared the terrible consequences.

This ancient story contains a lot of wisdom: When faced with the opportunity to give our gifts to the world, we often run the other way like Jonah did. We hide our light under a bushel. Only when we face adversity do we wake up and realize that we can only fulfill our purpose if we give what we are here to give, in other words, if we let our light shine for others.

In the course of my work on the Abraham Path, I have had the privilege of studying the ancient stories about Abraham. In the biblical story, Abraham hears the call from God to leave his country and the house of his father and go to a place where he will be shown his true self. In direct contrast to Jonah, Abraham immediately heeds the call and sets off on a journey to follow his destiny. The sages of old used to debate why of all people at the time, only Abraham was selected to receive this call. What made him especially deserving? After much discussion, the sages came to the conclusion that, in truth, each human being receives the call. The only difference was that Abraham listened.

Abraham’s gift was the simple but powerful lesson of hospitality. As a stranger in a strange land, he received hospitality and he gave hospitality. His tent was said to be open in all four directions to receive guests. The gift that Abraham discovered in himself was to show kindness to strangers. He learned to let his light shine on others. What I have come to appreciate is that perhaps each of us is a bit like Abraham, called to embark on a journey into the unknown. Each of us is given a certain gift that is ours to give, a light within. It is simply up to us to clean the window that looks out and to let our light shine for others.

I have described earlier in the book the case of my friend and client Abilio Diniz as an example of someone who was trapped in a win-lose fight from which there seemed to be no exit. I would now like to describe how the fight ended.

Throughout the two and a half years of struggle with his former business partner, in which they had sued each other, attacked each other in the press, and blocked each other’s initiatives to help their company grow, they had tried to take what they wanted from the other—and failed. Neither had succeeded in getting what he really wanted.

When my colleague David and I met with the other side’s negotiator, we sought to change the dynamic: instead of presenting the other side with a list of threats, we focused on what each side had the power to give the other. Behind all the conflicting positions, Abilio and his partner had two interests in common: freedom and dignity. Each party had the power to offer the other the freedom he wanted to pursue business deals. And each party could offer the other the respect he valued. We proposed that an agreement founded on these two common interests—freedom and dignity—could be a win-win agreement, however difficult that was for the parties to imagine at first.

We discussed how to make such an agreement tangible. Abilio’s partner could release Abilio from a three-year noncompete clause, giving him the freedom he sought to make other business deals. In return, Abilio could agree to leave the board, leaving his partner free to run the company the way he wanted. His partner could exchange Abilio’s voting shares for nonvoting shares that Abilio would then be free to sell in the stock market. Both parties could release a joint press statement wishing the other well. And so on. In short, the game could shift from win-lose to win-win.

There were many difficulties and legal complexities, of course, but this simple change in the dynamic from taking to giving made all the difference. In four intense days, the parties were able to get to yes and put a final end to this bitter business battle. Abilio gave a gracious farewell talk to the company’s executives and another to all the employees in which he spoke respectfully of his former partner and wished all of them well. His partner offered Abilio a valuable athletic training organization, belonging to the company, which had been a real passion for Abilio.

What was truly astonishing to all concerned was the degree of satisfaction expressed afterward by both Abilio and his partner, hitherto archenemies. It was not a barely acceptable compromise that each grudgingly agreed to, but a solution that left each feeling remarkably satisfied and relieved with the outcome.

Starting the negotiations by focusing on what they could give each other, rather than what they could take resulted in a genuine win-win outcome. In fact, it went well beyond a win-win to a win-win-win solution as the benefits spread far and wide beyond the two parties to their families, to the company and its hundred and fifty thousand employees, and even to the society at large.

It was not an easy process for Abilio. Like most of us, he began as his worthiest opponent. But he worked hard to turn himself into an ally. With a strong tendency to react by attacking, he tried his best to go to the balcony, even if not always successfully. While he judged himself harshly at times, he also made great efforts, with the help of others, to put himself in his own shoes and uncover his true needs. While occasionally he blamed the other side, he always remembered in the end that he alone was responsible for his life.

At times Abilio fell prey to the fear of scarcity, but then he reframed his picture of life and remembered his power to make his own happiness. Whenever he got trapped in the past, he was able to come back to the present moment to see what could be done. A real fighter, he took an antagonistic stance, but he remembered when it was important to offer respect to his adversary. The last obstacle for Abilio to overcome was the win-lose mindset, which he did by changing his attitude from taking to giving.

Like just about everyone, Abilio was imperfect in the process of getting to yes with himself, but his disciplined efforts to get out of his own way were sufficient for him to succeed in getting to a big yes he wanted with the other side. “I got my life back,” he told me. “These are the best times in my life.”

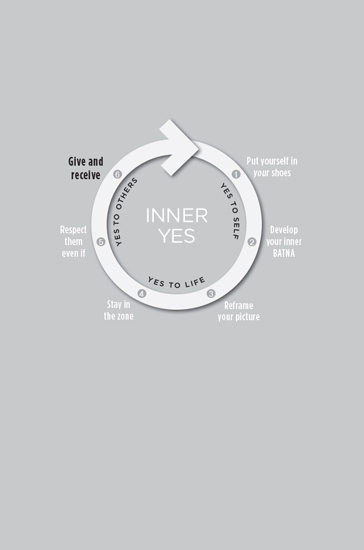

Each one of the six steps helps us to transform the win-lose mindset into a win-win-win mindset. The crowning move is to shift our basic underlying attitude toward others from taking to giving. At first we may give in order to receive, then we learn to give without receiving a direct return, and finally we learn to give in fulfillment of our purpose. By changing our basic default mode to giving, not only can we get to yes with ourselves, experiencing inner satisfaction, but we will also find it easier to get to yes with others, achieving outer success. Thus begins a circle of giving and receiving that has no end.