How does a fish see the river it is swimming in? It cannot leave the water to gain distance or perspective. Something like that is happening in Berlin. Everything is flowing. Every moment there are new events, reports; whenever I step out of the front door, within a couple of minutes I become part of a swirling crowd, people shouting newspaper headlines at me: Farewell to the island! Germany is one! The people have triumphed! Eight hundred thousand conquered West Berlin! At the banks and post offices, long queues of East Germans stand in line for their “welcome money.”1 Old people with dazed expressions, in this part of the city for the first time in thirty years, come in search of their memories; young people who were born after the Wall went up, and who live maybe a kilometer away, walk around in a world they have never known, so ecstatic that the asphalt can barely hold them.

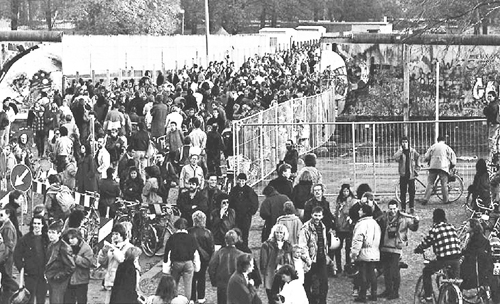

As I write these words, church bells are ringing out on all sides, as they did a few days ago when the bells of the Gedächtniskirche suddenly pealed out their bronze news about the open Wall and people knelt down and cried in the streets. There is always something ecstatic, moving, alarming, about visible history. No one can miss it. And no one knows what is going to happen. This is a city that has been through so much. The tens of thousands of people flowing through the eastern channels to the West all bring their emotions with them as though they are tangible objects. Their feelings are reflected in the faces of the people on this side and boosted by the sound of their own millions of footsteps in the suddenly pedestrianized streets, by the sirens and church bells, by the voices with their questions and rumors, the unwritten words of a script invented by no one. No one, and everyone. “Wir sind das Volk!” they called out in Leipzig only two weeks ago. We are the People! Now those people are here and they have left their leaders at home.

The big demonstration in East Berlin happened eight days ago. Simone went, but was singled out by the unerring eye of the border guards at Bahnhof Friedrichstraße. No, she could not go through. “So why are all these other people allowed in? I’ve been waiting here for an hour and a half, just like everyone else.” “I’m sorry, but we don’t have to give a reason. Try again tomorrow.” I was off on another mission at the time, a series of readings in the far West: Aachen, Cologne, Frankfurt, Essen. Even there, Berlin was constantly present in every conversation. Monday evening was Essen, the dark heart of the Ruhr-gebiet. After the reading, a discussion in a dimly lit café, Erbsensuppe, Schlachtplatte, big glasses of beer. A number of young people, a girl from the theater, a book dealer, a biochemist, a writer. Always the same words, over and over again: Übersiedler, Aussiedler, Wiederver-einigung. Aren’t people in Holland scared of German reunification? No? Well, we are. We don’t want to be reunified, and certainly not with those Saxons and Prussians. They’ve had such authoritarian upbringings; they don’t know any better. They’re at the factory gates by six every morning. How are we supposed to respond to that? They may be Germans, but they’re different Germans. Of that lot 10 percent would vote for the Republikaner, and 60 percent for the Christian Democrats (C.D.U.). We know that already; we’ve seen the surveys. Germany will be one big country again, but leaning eastwards, towards the Poles and the Russians. That’s sure to make the rest of Europe happy. Is that what you want? The whole balance will shift and we’ll have to become one big nation again.

Queue for Begrüßungsgeld (“welcome money”), West Berlin, November 1989

The only answer I can think of is that they already are one big nation, that it is their own relative density that will put an end to this artificial separation. Large countries exert their own gravitational force, which sooner or later draws everything in. It will be up to the Germans themselves to deal with the consequences.

After our conversation, they take me to catch the last train to Cologne, a kind of tram. It is a tortuous journey. The thing is empty, and cold, and stops everywhere, even when there is no one in sight. Outside, the grim silhouettes of heavy industry, hellish flames against the blackness. At Düsseldorf, there is a bomb scare and we come to a standstill in the midst of a silent black void. I am alone in the compartment. I hear the elderly voice of the driver over the loudspeaker, breathing heavily: Bombendrohung, a bomb scare. We wait there, endlessly, and whether it is the night, or the absence of other people, or the conversation I had that evening, or simply my age, I cannot help thinking about the war, about the power of attraction exerted by this strange country, which always drags other countries into its destiny, whether it means to or not.

Thursday evening. I am back in Berlin and in a taxi with my photographer and a friend. As we are talking, suddenly I hear something in the sound of the voice on the car radio, a sound I recognize: the eager, rushed, incredulous tone of major events. I ask the driver to turn up the volume, but that is not necessary; she tells us the news herself now that she knows we can understand her. She is excited, she pushes back her long blonde hair, and she is almost shouting. The Wall is open, everyone is on their way to the Brandenburger Tor, all of Berlin is heading there. If we want, she can take us there now, as she wants to see it too. If we agree to head straight there, she says she will turn off the meter. The traffic is heavier by the second; it is almost impossible to move forward, even from a hundred meters beyond the Siegessäule. In the Trabant beside us, smoke billowing out behind it, young East Germans hold up their visas to show us, their faces white with excitement in the glow of the streetlights. I tell the driver that she would be better off taking John-Foster-Dulles-Allee to the Reichstag. Dulles, Reichstag, war, Cold War—it is impossible to say anything here without invoking the past. The dark ship of the Reichstag lies in a sea of people; everyone is advancing on the tall columns of the Brandenburger Tor and the galloping horses above them, which once stormed in the opposite direction. The viewing platform that looks out over Unter den Linden is swaying under the weight of the people. We fight our way through and whenever someone comes down, we move up, one body at a time. The empty semi-circle in front of the columns is illuminated by an artificial orange light; the phalanx of border soldiers inside the semi-circle seems a weak line of defence against the strength of the crowd on our side. Whenever someone climbs up onto the Wall, the soldiers try to spray them back down, but the jet is usually not strong enough and the lonely figure stays there, soaked to the bone, a living statue within a nimbus of illuminated white foam. Shouting, cheering, the flashes of a hundred cameras, as though the concrete of the Wall has become transparent, as though already it is almost no longer there. Young people dance in the jets of water, the vulnerable line of soldiers forming a backdrop for their ballet. In the semi-darkness, I cannot see the soldiers’ faces, and all they can see is the dancers. The others, the large animal of the crowd, which is growing larger and larger, can only hear them. This is the destruction of their world, the only world they have ever known. The taxi driver does not use the meter on the return journey either. She says she is happy, that she will never forget this moment. Her eyes are gleaming. Her boyfriend is somewhere by the Wall right now and she would like to share this moment with him, but she does not know where he is, and besides, her shift runs until six in the morning.

Brandenburger Tor, November 4, 1989

The next morning, Friday. I am standing in the window of Café Adler, the last café in the West, by Checkpoint Charlie. “You are now leaving the American Sector”—today that means nothing. Everything seems to be peeling away at an incredible speed. A gentle stream of Trabants comes flowing over the border. Someone is handing out money to the people in the cars; someone else is giving them flowers. The people in the cars are crying or looking bewildered, as though it cannot be true that they are driving in that place, that those other people are waving and calling to them. The East German border guards are standing on the other side of the street, a few meters away from their Western counterparts. They do not speak to one another, but stand firm in the surging crowd. I find their faces as unreadable as they were in the darkness yesterday. Then I cross to the other side myself, join the line, and I find that everything is the same as ever: visa, five Marks, the desperate exchange rate of one to one, even though the actual rate is ten to one. It goes quickly, and I am through within fifteen minutes, but the queue on the other side stretches endlessly around the corner into Friedrichstraße. I walk to the street where Volk und Welt is based, the publishing house that brought out two of my books. It is quiet there, but the door is open. I find one of the proofreaders and am greeted with Berlin humor: “How kind of you to come and visit, just when everyone else is heading in the other direction!” But it is clear that they have been engulfed by the events. No one has any idea what will happen next. I say that I have heard from a Hungarian friend that after the “change” there—I do not know a better word for it—over two hundred new publishing houses were set up. Of course, they know that already, but their greatest concern if that were to happen would be how to get hold of enough paper. No one has anything sensible to say about reunification: “How would it work economically? No one here can afford books from the West. Our books only cost a couple of Marks.” They have a brilliant series of foreign literature—from Duras to Frisch, Queneau, Kawabata, Canetti, Cheever, Calvino, Bernlef, Sarraute and Claus—but what is going to happen when West German publishers are free to operate in the East? Will Volk und Welt still be able to acquire publishing rights? Hundreds of these questions are going around; the whole country is one big question without an answer, and every possible, unimaginable answer, economic or political, intimately affects the lives of millions of people.

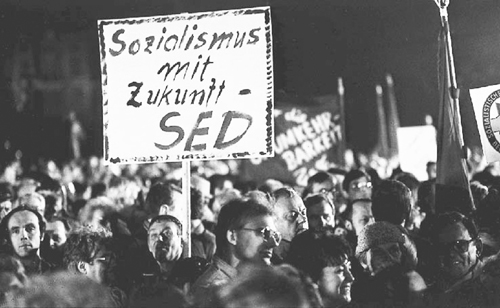

S.E.D. (Sozialistische Einheitspartei Deutschlands) demonstration, East Berlin, November 10, 1989

“The world has become glass,” the proofreader says, a sentiment I retain when I head back outside. It is cold, but the sun is shining on the chariot atop the Brandenburger Tor. Now I am seeing the city where I live from the other side—that is still possible for now. Masses of Westerners are standing on the Wall; cameras from C.B.S. and the B.B.C. are filming the silent waves and cheers, the distant ecstasy. In the classic no-man’s land between here and there, officers stride past a backdrop of columns just as they always have done, sunlight glinting on their epaulettes.

Potsdamer Platz, West Berlin, November 12, 1989

Glass: the word will not let me go. I walk across Unter den Linden and see a luxury edition of the collected works of Erich Honecker in the window of a large bookshop. The books are miniatures, thumb-sized, with leather bindings: Alles für das Wohl des Volkes. Their tiny format appears to reflect the fate of the vanished leader. They cost 420 Marks. How long ago is it now, that kiss from Gorbachev? On all sides, the buildings are tall, old, powerful. This was once the real center of a major metropolis, but only now do I feel how just big it was, how big it will be again when it is a single, united city. The capital of an empire? Frederick the Great never left; he rides his horse, frozen in his heroic pose. Figures on the Neoclassical buildings dance their stone dance in the last of the sunlight. Two soldiers stand, so motionlessly, in front of Schinkel’s Neue Wache, while opposite, on Bebelplatz, a memorial plaque serves as a reminder of a book-burning: “Auf diesem Platz vernichtete nazistischer Ungeist die besten Werke der deutschen und der Weltliteratur.”2 And only a short distance away: “LENIN arbeitete im Jahre 1898 in diesem Gebaüde.”3 Can I tell that things have changed just by looking at these people? No, I can see no difference. They are walking and shopping with no indication that half of their city is flowing into the other half at this very moment.

Potsdamer Platz, West Berlin, November 12, 1989

Marx and Engels, East Berlin, November 1989

I cross the dark water of the Spree and come to Das Rote Rathaus, the Red Town Hall, where every Monday evening the demonstrations took place that made the world shake. I walk across the grass in front of the building, towards the backs of Marx and Engels. One is standing, the other is sitting; I recognize them even from behind, by the wavy hair, the wide, jutting beard of the seated man. Their world too seems to be made of glass: fragile, transparent. They are still here, but already somehow departing, disappointed at what has become of their legacy, their backs to the illuminated glass palace of their descendants, the Palast der Republik. A few hours later, the last of their heirs arrive to stage a counter-demonstration. It is dark now; powerful halogen lights shine upon the Reconciliation Door of the Berliner Dom. Another crowd, but this one is not demanding, it is defending, giving itself fresh heart with slogans and banners and mechanical battle songs that come from large loudspeakers. I allow myself to be swept forward across the gravel between the statues, up to Das Alte Museum with its columns and watchful eagles. Members of the press are climbing into Schinkel’s giant marble dish in front of the building. From the steps, I have a good view of the banners: Weiter so, Egon. Sozialismus mit Zukunft: S.E.D. (Keep it up, Egon. Socialism with a Future: S.E.D.), but also Für die Unumkehrbarkeit der Wende (The Wende—for irreversible change!) and Kommt raus aus Wandlitz, seht uns ins Antlitz (Come out of Wandlitz4 and look us in the face). And that is what I do: I look into the faces of the Party members. They are the people who have the most to lose from the changes. In free elections, the S.E.D. would receive only 12 percent of the vote, and most of the people here would disappear into the obscurity where a number of their leaders already reside, has-beens, dispensed with. Some of them sing along hesitantly with the amplified songs about blood-red banners and battle, but the mood is uncertain. The world around them is now a different place. They know what has happened in Poland and Hungary; they have come here to feel safe among the loud voices, but even those voices are saying things they have never said before. Party members are speaking, blaming their leaders for being too late—too late and too slow—they are constantly being overtaken by events. Members who were voted into the Politburo on Wednesday have been thrown out today, and no one knows where they stand. The “monopoly on truth” has been abandoned, and everything sounds like heresy. A few of the speakers say they are happy that they did not have to submit their speeches to the Party for approval, as they used to. Most of them receive more applause than Krenz, who speaks about a revolution on German soil, but the people standing there know that it is not their revolution. He also talks about free elections, but says that the Party will not allow the power to be taken from its hands. Niemals, never. What is the validity of such words? Like a group under siege, the leaders appear in Welt am Sonntag the next day: raincoats, raised fists, mouths open as they sing a battle song. By now, all over the city, pneumatic drills are banging the first holes through the Wall. I leave before the crowd disperses. Behind the windows of the Palast Hotel, a palm-court ensemble in dinner jackets plays to an audience of Bulgarians and Koreans.

“Socialism with a future—S.E.D.”

“Nobel Peace Prize for Gorbachev,” S.E.D. demonstration, East Berlin, November 10, 1989

There is still a queue at Checkpoint Charlie. Foreigners can leave by a separate exit and do not have to wait. The same border guards as this morning, their faces exhausted, pale, tense. I exit as an East Berliner, because a young woman offers me chewing gum and a boy hands me a pamphlet about Einigkeit und Recht und Freiheit—unity, justice and freedom—and the Wall having to come down and reunification being inevitable, and McDonald’s would like to treat me to “1 small drink, Voucher valid until 12.11.89.” So I too am welcomed as a home-comer. In the U-Bahn station at Kochstraße, the thousands wait for a train, offering no resistance as they are pushed through, into the West. When I finally reach Kurfürstendamm, Berlin is one big party. Cars can no longer get through, and the city has descended into madness. The people have become one whirling body, a creature with thousands of heads, undulating, rippling, flowing through the city, no longer knowing whether it is moving or being moved, and I flow along with it, having become crowd, news picture, nobody. News bulletins appear on the wall of a building on the Ku’damm, in lines that quickly fade, as though the news might catch up with them, but nothing can catch up with this crowd, because it is making the news itself. The crowd knows that, and it feels like a mass shiver. They themselves caused what they are reading here, they are the people; after them will come the politicians with their words, but for now those words seem to have the aim of calming, pacifying, more than anything else. No one will ever really know the entire story, but in the past few weeks the people on these streets have turned a page of history, and not only the Krenzes, but also the Kohls, the Gorbachevs, the Mitterrands and the Thatchers will have to wait and see what is written on the next pages, and who will appear on them. Millions of Europeans from the East have caught up with the signatures of Yalta and overtaken them, and we did not assist them.

A Mauerspecht (wall woodpecker) pecking away. Potsdamer Platz, West Berlin, November 12, 1989

Thirty-three years ago, I stood in Budapest in a different crowd, one that felt betrayed and abandoned by us. That was history too, the black mirror image of the day I am experiencing now. I watched the Russian army surround the city and wrote my first piece for a newspaper, which ended with the words, “Russians, go home.” I can laugh at my own ignorance now, but how loud should my laughter be?

There are still Russians in the D.D.R., just as there are Americans in the Bundesrepublik. They are two different countries and the Wall is still there, even though there are holes in it. But the people from that Other Country are walking along these streets for the first time in thirty years, and when I look out of the window, I can see them.

November 18, 1989

Checkpoint Charlie, West Berlin, November 10, 1989

1 Between 1970 and December 29, 1989, each visitor from the D.D.R. to West Germany was entitled to Begrüßungsgeld, a financial gift from the government. After the fall of the Wall demand grew so high that it was abolished.

2 On this spot, the inhumanity of National Socialism destroyed the best works of German and world literature.

3 Lenin worked here in the year 1898.

4 A municipality to the north of Berlin, home to many top East German functionaries.