7Eye Tracking and the Process of Dubbing Translation

Kristian Tangsgaard Hvelplund

Introduction

Dubbing translation is quite different from most other types of translation as it involves not only the processing of written text but also the processing of information from other semiotic channels. In addition to dealing with the source text (ST) and target text (TT) manuscripts, translators need to coordinate and organise information from acoustic as well as visual channels during the translation process. The translator must be alert to the dual function of the TT: the finalised TT manuscript should serve as a useful point of departure for dubbing actors to record the translated dialogue in the target language (TL), and the dubbed dialogue, subject to the interpretation of the dubbing actors and director, should convey the original language message to the new TT audience. The translator thus needs to take into account a variety of issues such as register, style, terminological accuracy, synchronicity and so on. While the complex nature of dubbing is fascinating from a cognitive perspective, the cognitive processes that underlie this type of translation are not yet well understood. Having found its inspiration mainly in the cognitive sciences, research into the processes underlying more traditional types of translating has been going on for decades, and recently eye tracking has been adopted as a central method to tap into the comprehension and production aspects of translation. In audiovisual translation (AVT), eye tracking has been used almost exclusively to explore reception aspects, with the resulting situation that the production dimension has until now been largely ignored and the potential to explore how the mind works with polysemiotic translations remains largely untapped. The benefits of having a better understanding of the cognitive processes of dubbing are similar to those of having a better understanding of the cognitive processes of translation considered more broadly: to be able to model and predict translator behaviour in order to improve and optimise translators’ translation processes. Insights into the cognitive processes of dubbing are of potential interest to pedagogical and didactic initiatives in the training of dubbing translators, and they can add valuable information to the discussion of what characterises and differentiates them from translators who work with other types of translation. More broadly, a better understanding of dubbing translation processes is important in understanding the human mind’s ability to coordinate cognitive effort in tasks, which require shifting focus between multiple semiotic channels.

Process-oriented approaches constitute a very useful methodology to investigate these and other matters concerning dubbing, and this study examines how cognitive effort is allocated and coordinated when translating for dubbing. Using eye tracking technology to find out where novice dubbing translators look at the computer screen during the translation process, the aim is to get an initial impression of the cognitive processes underlying this type of translation. More specifically, the study investigates how translators allocate cognitive resources during the translation process; it discusses the translator’s processing flow and examines the load placed on the translator’s cognitive systems during the translation process. The findings may serve as an inspiration for future work in the interdisciplinary field of AVT and translation process research.

Dubbing Translation, Cognitive Processes and Eye Tracking

A type of polysemiotic translation (Gottlieb, 1994), dubbing involves the combination of visual as well as aural information, and often also written text, to compose a written dialogue manuscript in the TL. Dubbing translators are tasked with translating a special kind of text, an audiovisual (AV) text, which, by Chaume’s (2004: 16) definition is ‘a semiotic construct comprising several signifying codes that operate simultaneously in the production of meaning’. Depending on the material available, dubbing requires at least five sources of information, namely, the ST manuscript, the AV film material, the TT manuscript, monolingual and bilingual dictionaries. Dubbing translators need to take into account all these sources of information during the translation process, and combine and coordinate information from multiple sources and different channels to create a TT that fits the genre of a dubbing manuscript with its inherent focus on synchronicities.

The cognitive processes involved in translation production in general have attracted the attention of researchers since the mid-1980s. In translation process research, methods to empirically explore the cognitive workings of the translator’s mind have been inspired by cognitive sciences, including psychology and experimental psychology and, by derivation, neighbouring disciplines such as psycholinguistics, reading research and writing research. These methods include think-aloud protocol analysis, keylogging and recently also eye tracking (Göpferich et al., 2008; Hvelplund, 2014; O’Brien, 2006). Eye tracking, used in the present investigation, is a method to measure and register where the eyes gaze with the assumption that the position of the eyes’ gaze accurately reveals the object of thought. The eye–mind assumption, proposed by Just and Carpenter (1980), is often used as a basis for assuming such a link between visual focus and mental focus. While it is true that eye gaze and object of thought are not always in sync, the majority of visual activity during a cognitively demanding task such as dubbing has the potential to reveal concurrent cognitive processing (Hvelplund, 2014).

For decades, eye tracking has been used in the cognitive sciences to make observations on cognitive processing and it has become increasingly popular in recent years in translation studies to make observations on the cognitive processes involved in translation. In AVT, eye tracking has been used mainly in reception studies (Künzli & Ehrensberger-Dow, 2011; Perego, 2012), aimed at investigating viewers’ responses to subtitling.

Processes of dubbing translation

As in any other type of translation, dubbing involves the identification of ST meaning and its recreation in the TL. Provided an ST manuscript is available to the translator, ST processing involves a range of different tasks. During ST processing, the translator reads the ST for comprehension and constructs meaning hypotheses (Gile, 1995) through lexical and propositional analysis (Kintsch, 1988) of the ST material in order to create a meaning representation of the ST. During TT processing, the translator reformulates the ST meaning representation in the TL, types the translation in the TT manuscript and encodes the manuscript with time stamps, while TT processing involves reading and rereading the TT. In addition to ST and TT processing, dubbing also involves the processing of the visual and aural reception of the film material including the specific tasks of meaning hypothesis generation, meaning hypothesis validation of a meaning hypothesis generated during ST reading, identification of possible TL renditions of an ST item and identification of timecodes. Unlike ST and TT processing, film processing involves the coordination of information from multiple channels and may therefore be more cognitively demanding than other dubbing processes. The indexation and separation of processes is probably not as categorical as indicated here, and cognitive processes during translation do in fact overlap and occur in parallel (Balling et al., 2014). However, the indexation is helpful in clarifying the subprocesses that, for the most part, are associated with a given activity. The present chapter investigates if and to what extent the various subtasks of dubbing differ from each other in terms of cognitive effort and, more specifically, how translators distribute cognitive effort during dubbing, by looking at the amount of gaze activity that the different parts of the dubbing translation process attract. It also focuses on the cognitive load that the various dubbing subtasks have on the translator’s cognitive system, by examining measures of fixation duration and pupil size. It should be noted that other activities, such as consultation of print dictionaries or parallel texts are also part of dubbing. However, since those processes are unavailable in the eye tracking setup of this study, they will not be dealt with in this chapter.

Eye tracking indicators

Three eye tracking indicators are used in this study to investigate the cognitive processes in dubbing translation: fixation duration, pupil size and attention shifts. A popular measure in the cognitive sciences and in translation process research, fixation duration, is measured in milliseconds and used as an indicator of the workload placed on the cognitive system (Holmqvist et al., 2011; Rayner, 1998). Following Just and Carpenter’s (1980) eye–mind assumption, longer fixations are often taken to indicate that more cognitive effort is involved in a task while shorter fixations indicate the opposite. Put differently, longer fixations suggest that something is more complex to process and shorter fixations indicate that something is less complex to process. The combined duration of fixations for a given subtask is used to calculate how long the translators spend processing the different parts that make up dubbing translation. Pupil dilation, sometimes referred to as pupil size or pupillary movement, is measured in millimetres and is also used as an indicator of cognitive effort as larger pupils suggest that a task is more cognitively demanding, while smaller pupils indicate the opposite (Hess & Polt, 1964; Holmqvist et al., 2011). Attention shifts (Hvelplund, 2011) are used to identify the processing flow, i.e. the scan path of the eyes between the different screen elements (ST, TT, film and dictionary) involved in dubbing.

Research Design and Methodology

This section explains how the study’s data were collected and analysed. It provides information about the participants, the task that they carried out, the data collection sessions and the statistical method used to analyse the compiled data.

Participants and task

Seven participants had their translation processes monitored and recorded using the Tobii X120 eye tracker. They were translation students in the master’s programme at the University of Copenhagen and had basic experience with dubbing translation and knowledge of eye tracking methodology from course work. The nature of the experiment required that the participants had (1) familiarity and experience with the particular dubbing arrangements used during the recording, and (2) familiarity with eye tracking, so that they would not be surprised by the experimental-like setup. While it is generally recommended to have at least 10 participants (Balling & Hvelplund, 2015) in a quantitatively oriented study such as the this one, the present pool of participants was considered sufficient to gain preliminary insights into the cognitive workings of the dubbing translator’s mind. Data were collected at the University of Copenhagen under the same conditions: window blinds were drawn, the same artificial light was lit and they were given the same translation brief. Data from one participant were discarded due to poor eye tracking data quality. Some participants studied language combinations other than English and Danish, but they all reported English as their second language (L2) and Danish as their first language (L1). The present study therefore considers the participants’ cognitive processes illustrative of those generally involved in novices’ L2 English to L1 Danish dubbing translation.

The participants carried out two translation tasks. The first task was an English to Danish translation of a 124-word synopsis of a US-Canadian animated television show aimed at children in the 8–14 years age group. It served only as a warm-up task to prepare the participants and acclimatise them for the pending main task. Upon completion of the warm-up task, the participants were asked to create a TL dubbing manuscript in Danish, which would be used by actors in a recording studio, based on an as-broadcast ST script and AV material. The clip for the main task was a 2-minute extract (284 ST words) of the same US-Canadian animated television show and the participants had access to an online English-Danish-English dictionary (www.ordbogen.com).

Experimental setup and analysis

A Tobii X120 eye tracker was used to register the participants’ eye movements during the translation session. The eye tracker records the position of the gaze on the monitor with a frequency of 120Hz (120 impressions per second) and a spatial accuracy of 1degree (around 1centimetre inaccuracy between the registered visual focus and the actual visual focus). For the purposes of the present study, these temporal and spatial resolutions are sufficient enough to make reasonably detailed observations of the gaze activity in dubbing translation.

The ST manuscript was presented in the upper left part of the computer screen while the TT manuscript was presented in the lower left part of the screen. In the upper right part, an online dictionary was available and the film material occupied the lower right part of the screen, as shown in Figure 7.1.

Figure 7.1 Four rectangular AOIs (with blue edges) superimposed on four screen elements in dubbing translation

Tobii Studio, which is the X120 eye tracker’s recording and analysis software package, was used to record eye tracking data and R, a software programme for statistical analysis, was used to analyse the eye tracking data. Although the recording/analysis software in this study was used only to record data, it does provide descriptive figures such as average fixation duration, total gaze time and other summarised fixation-based measures. The analysis software does not, however, provide information about the participants’ pupil sizes, nor does it provide information about the duration of each individual fixation during a recording – information which is necessary in order to go beyond descriptive statistical analysis and treat the data inferentially, thus permitting more generalisable conclusions to be drawn. Pupil size measurements and information about individual fixations are only accessible from Tobii Studio’s so-called ‘raw’ recording of the eye tracking data. For this study, these raw data were exported from Tobii Studio and then imported into R, where relevant statistical figures for fixations, pupil sizes and attention shifts were computed (see the following section).

In order to identify the eye movement activity that is related to a specific subtask of dubbing translation (ST processing, TT processing, film processing and dictionary consultation), specific areas of interest (AOIs) were defined, as illustrated in Figure 7.1. This categorisation of AOIs according to the different visual elements of dubbing translation makes it possible to consider separately the eye movement behaviour that occurs during the various subtasks of the translation process.

Statistical analysis

Two types of statistical methods are used in this study to analyse eye movement behaviour during dubbing. Descriptive statistics provides an overall indication of the translators’ processes, and inferential statistics is used to assess in greater detail the extent to which there is a significant difference between the various subtasks involved in the translation process. The former gives only a rough description of the surface characteristics of the data, often expressed in summarised or averaged figures, and it is difficult to draw solid conclusions that could be generalised beyond the sample unless the descriptive differences have been tested for significance (Balling & Hvelplund, 2015). In order to be able to generalise beyond the sample, inferential statistics has been used.

For each of the inferential analyses to do with fixation duration and pupil size, linear mixed-effects regression (LMER) models were fitted in R to analyse data from naturalistically oriented experiments, as these models take into account fixed as well as random effects and thus constitute a powerful method (Balling, 2008: 176). LMER modelling assumes that the data set is normally distributed but as both fixation duration and pupil size data were non-normally distributed, the two sets were logarithmically transformed to achieve a normal distribution.

Once the data had been normalised, pairwise comparisons were carried out in order to examine if differences in fixation duration and pupil size between AOIs were significant. In R, a reference level (e.g. ST pupil size) was defined which was then compared with other levels (i.e. TT pupil size, film pupil size and dictionary pupil size). For each comparison, p- and t-values were calculated. The p-value indicates how likely it is that the null hypothesis is true: the lower the p-value, the more likely it is that the null hypothesis is false, and if the p-value is lower than 0.05, the difference between two subsets of data is significant. For instance, the difference (p<0.0001) between ST pupil size and TT pupil size can be said to be significant. The t-value is an estimate of the differences in the means between two subsets of data. A positive t-value (t=17.98) indicates that the factor level (e.g. TT pupil size=3.45 mm) is greater than the reference level (e.g. ST pupil size 3.39 mm). A negative t-value indicates that the factor level is smaller than the reference level.

Results and Discussion

In this section, the findings from each of the three analyses are presented and discussed. The first analysis, distribution of attention, gives an overall impression of where the translators looked and how much time was spent looking at the various screen elements. The second analysis, processing flow, presents and discusses the translators’ sequence of processing of the different screen elements and comments also on the translators’ typing routines. The third and final analysis, cognitive effort, presents and discusses how cognitively demanding the different parts of dubbing translation were, using measures of fixation duration and pupil size.

Distribution of attention

More than a quarter (26%) of the gaze activity during dubbing translation is focused on ST processing while nearly half of the gaze activity (47.5%) is devoted to TT processing. Visual attention to the film segment, i.e. film processing, is around 21.6% and dictionary consultation constitutes only 4.9% of the combined gaze activity. No inferential analysis has been carried out in relation to distribution of attention as it is not meaningful to perform such an analysis since the data consist of only 24 observations, i.e. four AOI means (ST, TT, film, dictionary) for each of the six participants. The figures show that processes associated with TT reading, such as TL reformulation and the more mechanical task of typing the translation, are most time consuming and indicate that TT processing is more cognitively demanding than any other subprocess of dubbing. Processes involved in ST reading, such as lexical retrieval or semantic and syntactic analysis involve less time, while the tasks of film processing, such as verification of meaning hypotheses and location of timecodes are least time consuming. The figures suggest that TT processing requires the biggest processing effort during dubbing as the translators focus nearly half of all their visual attention on this part of the screen.

These percentages partly mirror findings from related studies investigating attention distribution in translation. Jakobsen and Jensen (2008: 114), for instance, found that reading during TT processing attracted nearly twice as much visual attention as ST processing for professional translators, whereas in the case of student translators, ST processing received slightly more attention than TT processing. None of the differences were tested for significance. In a more recent study, Hvelplund (2011) found statistically significant differences showing that the TT receives considerably more visual attention than the ST for both professional translators (ST=19.9%, TT=68.0%) and student translators (ST=27.8% and TT=64.8%). Interestingly, it seems that the amount of time allocated to ST processing during dubbing is comparable to traditional translation while the amount of time allocated to TT processing in traditional translation is split between TT processing and film processing in translating for dubbing.

Processing flow

For the present study, a processing flow is defined as the sequence in which various subtasks of dubbing translation are processed, as indicated by visual transitions between ST AOI, TT AOI, film AOI and typing activity. Combined, the study’s participants performed 3538 visual transitions, i.e. shifts of visual attention, between ST, TT and film AOIs. Table 7.1 is a matrix with the actual and relative figures for the number of transitions across AOI types.

Table 7.1 Transition matrix of ST, TT and film including typing

No inferential analysis has been carried out in relation to processing flow since they consist of only 36–72 observations, respectively, 6 and 12 AOI means (ST, TT, film) for each of the six participants. The figures in Table 7.1 illustrate a typical processing flow during dubbing. Starting with reading the ST manuscript, attention is first focused on the ST, then shifts to the TT, and from the TT is either refocused on the ST, which happens two thirds of the time (65.4%), or it shifts to the AV material (34.6%). From the film area, attention moves almost always to the TT area (80.2%). These figures strengthen the suggestion that TT processing is the nexus of information processing during dubbing as there is heavy traffic, i.e. many transitions, between (1) TT and ST and (2) TT and film, and relatively few transitions between ST and film. In fact, 91.6% of all transitions involve TT processing in one or the other direction, while the percentage is 67.6 for ST processing and 40.8 for film processing.

It is not clear from these figures how typing fits into the processing flow. Do translators start typing right after the ST has been read? Or does typing occur mainly when the AV material has been consulted? Or do they first need to consult the TT manuscript in order to proceed with their translations? The transition matrix in Table 7.2 reveals the actual and relevant relative figures for transitions to/from typing as well as between AOIs.

Table 7.2 Transition matrix of ST, TT and film

Transitions to typing from TT processing account for 2222 instances (80.6%) and from typing to TT processing are 2324 instances (85.1%). In other words, typing very often occurs right after/before the translator has looked at the TT manuscript, and it rarely happens right before/after ST and film processing. This means that translators, even though they might have established a meaning hypothesis during ST processing and validated it during film processing, almost always consult the TL manuscript right before typing a TL rendition of an ST item. These observations further support the suggestion that TT processing is the nexus of processing activity during dubbing. When TT processing immediately before typing, translators decide on a TL rendition within its contextual environment, and during TT processing immediately after typing, they perform verification tasks to ensure that the newly translated item has been rendered as intended in the TL and also to check for spelling and typing errors in the TT.

Cognitive effort

In the following, cognitive effort is examined by investigating differences in the translators’ fixation durations and pupil sizes. Cognitive effort is defined here as the mental energy allocated to a given task and, as noted earlier, a link is assumed between cognitive processing and manifestations of these indicators. Differences are reported descriptively in milliseconds (fixation duration) and millimetres (pupil size) and inferentially with p- and t-values for relevant comparisons. The analysis to do with fixation duration is based on 35,669 observations and the one to do with pupil size is based on 34,153 observations.

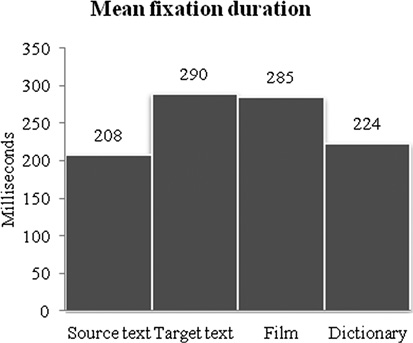

Figure 7.2 Mean fixation duration for ST, TT, film and dictionary

Fixation duration

The fixation duration means indicate that TT processing is by far the most demanding part of dubbing translation in terms of cognitive effort, as mean fixation duration is 290 ms. ST processing is the least demanding part, with a mean fixation duration of 208 ms (Figure 7.2).

The difference is supported by the inferential analysis which shows that the difference is highly significant (t=17.20, p<0.0001). Film processing is slightly less cognitively demanding than TT processing at 285 ms, but the difference is significant nonetheless (t=2.03, p=0.0425), while dictionary processing is significantly (t=–1.32, p<0.0001) more demanding than ST processing at 224 ms. In contrast to the distribution analysis, the generalisability of this present analysis is much stronger as the fixation duration analysis has undergone tests of significance.

Earlier studies in translation have also discovered that TT fixations are longer than ST fixations. Jakobsen and Jensen (2008) found that during the translation of news, texts fixations lasted 218 ms for ST and 259 ms for TT, and Hvelplund (2017) observed a similar pattern as ST mean fixation duration was 256 ms and 432 ms for TT. Outside translation, we also find variation in fixation duration which indicates that the kind of activity plays a large role in determining eye movement behaviour. Rayner (1998: 373), summarising previous research, reports that mean fixation duration during silent reading is 225 ms, much similar to the ST mean fixation duration found here, while mean fixation duration during typing, the type of reading which is most comparable to TT processing, is 400 ms. The fixation duration figures support the indication that TT processing during dubbing translation is more demanding than the other types of processing.

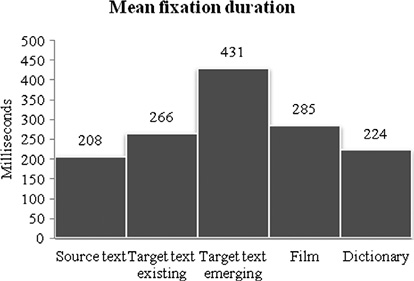

Fixations during film processing are also quite long and nearly as long as those during TT processing. A tempting explanation for the relatively long fixations is that film processing involves the complex combination and coordination of aural and visual information with an ST meaning representation and possibly also a preliminary representation of the ST message in the TL. This explanation is supported by eye movement research, which has found that mean fixation duration during scene perception is typically around 330 ms (Rayner, 1998). A counter-argument to this explanation, however, is that fixations during TT processing are in fact marginally (but significantly) longer. TT processing does not involve processing of aural and visual information in the same immediate manner as during film processing, and TT fixations should, from an intuitive perspective, be shorter than fixations during film processing. As this is not the case, a plausible justification for the relatively longer TT fixations may be found in the activity of typing. Indeed, TT processing often involves typing and it may well be that fixations are relatively longer because of the concurrent activities. Rayner (1998: 396) points out that a possible explanation for longer fixations during typing is that ‘the eyes wait in place for the hand to catch up’, which could mean that the eyes focus for longer on the same locale not because a particularly problematic item is being processed but because the mechanical operation of typing is slower than reading. In translation research, a significant difference has in fact been found between reading of emerging text (545 ms) and reading of existing text (319 ms) (Hvelplund, 2017). For dubbing, the present study also finds a significant difference between reading of emerging text and reading of existing text (Figure 7.3).

Figure 7.3 Mean fixation duration for ST, TT emerging, TT existing, film and dictionary

Fixations during reading of emerging TT (431 ms) are significantly longer than fixations during reading of existing TT (266 ms) (t=–27.52, p<0.0001), fixations during ST reading (208 ms) (t=–32.55, p<0.0001) and fixations during film processing (285 ms) (t=–22.51, p<0.0001). The reason for the longer fixations during reading of emerging TT is not necessarily that this subtask is more cognitively demanding than all the other subtasks. Rather, it is a combination of tasks of verifying and checking the TT – e.g. spelling errors – which are not likely to impose heavy cognitive demands, and of monitoring potentially slowly emerging text. Also an indicator of cognitive effort, the pupil size analysis below may prove useful in the discussion of the extent to which the long fixation durations are related to an increase in cognitive effort or whether they are a manifestation of a more mechanical operation of monitoring emerging TT.

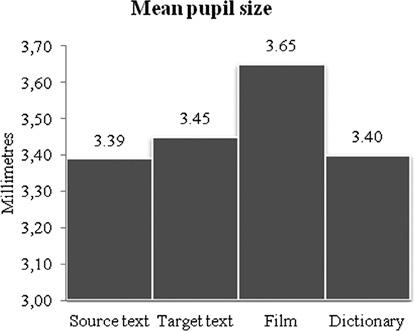

Pupil size

The pupil size measure also indicates that TT processing is more demanding than ST processing as mean pupil sizes are 3.45 and 3.39 mm, respectively (Figure 7.4). This is supported by the inferential analysis which found a highly significant difference (t=–17.98, p<0.0001). Dictionary processing is less demanding with a mean pupil size of 3.40 mm, while film processing, with a mean pupil size of 3.65 mm, is considerably more demanding than both TT processing (t=–43.03, p<0.0001) and ST processing (t=–54.55, p<0.0001). It is perhaps not so surprising that film processing is the most cognitively demanding of all subtasks since working with AV material involves the processing of aural, visual and possibly also textual information. While the overall amount of time allocated to the AV material is lower than that allocated to TT and ST processing, AV processing is the part of the dubbing translation process during which processing occurs with the highest intensity (Figure 7.5).

Figure 7.4 Mean pupil size for ST, TT, film and dictionary

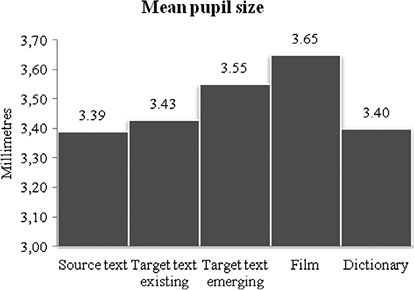

Figure 7.5 Mean pupil size for ST, TT emerging, TT existing, film and dictionary

The pupil size results contrast with the fixation duration findings reported earlier, and, as such, pupil size data and fixation duration data do not correlate as indicators of cognitive processing. However, as monitoring of text production is a factor which codetermines fixation duration, the two indicators might well correlate nonetheless, although the fixation duration, as an indicator of cognitive effort, should in general be treated cautiously if concurrent typing occurs during reading. Distinguishing between pupil sizes during reading of emerging and existing text, it turns out that film processing is the most cognitively demanding one while processing during reading of emerging TT comes second (t=–9.70, p<0.0001). Pupil sizes during reading of emerging TT are also significantly larger than during reading of existing TT (t=–24.026, p<0.0001), mirroring the findings from the analysis of fixation duration. The pupil size findings show that there is large and significant variation in the processing intensity across the subprocesses of dubbing translation.

Summary and Conclusion

The aim of this chapter has been to investigate the cognitive processes in dubbing. Involving decoding of information from several channels and encoding of ST content in the TL, with its inherent focus on synchronicities, dubbing translation is quite different from other types of translating and probably also quite cognitively demanding because of its polysemiotic nature. This study reveals that novice dubbing translators spend the majority of the translation process working with the TT, followed by ST processing and then the AV material. Quite interestingly, although the amount of time allocated to processing the AV material is less than that allocated to ST and TT processing, the pupil size indicator reveals that this part of the translation process is the one to tax the translators’ cognitive systems most. The reason for this is the concomitant processing of aural, visual and possibly also textual information from the AV material. The findings also reveal that working with the TL manuscript is at the centre of all translation activities; more precisely, TT processing is the nexus of processing activity since attention shifts for ST processing, film processing and typing occur most frequently to or from the TT.

It is likely that this study’s findings could extend to subtitling since the two translation modes are similar in some ways. Given the polysemiotic similarities of dubbing and subtitling, the processing flow during subtitling as well as the allocation of visual attention is likely to be quite similar to dubbing. Future studies could also focus on the differences between novices and professionals and explore how professionals structure their dubbing processes. This would be useful to model experts’ prototypical processing, and the findings would be instrumental in identifying weaknesses and undesirable behaviour in novice translators’ dubbing translation processing and could be potentially central to future translator training.

References

Balling, L.W. (2008) A brief introduction to regression designs and mixed-effects modelling by a recent convert. In S. Göpferich, A.L. Jakobsen and I.M. Mees (eds) Looking at Eyes. Eye-Tracking Studies of Reading and Translation Processing. (Copenhagen Studies in Language 36) (pp. 175–192). Copenhagen: Samfundslitteratur.

Balling, L.W. and Hvelplund, K.T. (2015) Design and statistics in quantitative translation (process) research. Translation Spaces 4 (1), 170–187.

Balling, L.W., Hvelplund, K.T. and Sjørup, A.C. (2014) Evidence of parallel processing during translation. Meta 59 (2), 234–259.

Chaume, F. (2004) Film studies and translation studies: Two disciplines at stake in audiovisual translation. Meta 49 (1), 12–24.

Gile, D. (1995) Basic Concepts and Models for Interpreter and Translator Training. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Göpferich, S., Jakobsen, A.L. and Mees, I.M. (eds) (2008) Looking at Eyes: Eye-Tracking Studies of Reading and Translation Processing. (Copenhagen Studies in Language 36). Copenhagen: Samfundslitteratur.

Gottlieb, H. (1994) Subtitling: People translating people. In C. Dollerup and A. Lindegaard (eds) Teaching Translation and Interpreting 2 (pp. 261–274). Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Hess, E.H. and Polt, J.M. (1964) Pupil size in relation to mental activity in simple problem solving. Science 143, 1190–1192.

Holmqvist, K., Nystrom, M., Andersson, R., Dewhurst, R., Jarodzka, H. and van de Weijer, J. (2011) Eye Tracking: A Comprehensive Guide to Methods and Measures. New York: Oxford University Press.

Hvelplund, K.T. (2011) Allocation of Cognitive Resources in Translation: An Eye-tracking and Key-logging Study. PhD thesis, Copenhagen Business School.

Hvelplund, K.T. (2014) Eye tracking and the translation process: Reflections on the analysis and interpretation of eye-tracking data. In R. Muñoz Martín (ed.) Minding Translation | Con la traducción en mente (MonTI Special Issue 1) (pp. 201–223). Alicante: Universidad de Alicante.

Hvelplund, K.T. (forthcoming) Four fundamental types of reading during translation. In A.L. Jakobsen and B. Mesa-Lao (eds) Translation in Transition. Between Cognition, Computing and Technology (pp. 55–77). Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Jakobsen, A.L. and Jensen, K.T.H. (2008) Eye movement behaviour across four different types of reading task. In S. Göpferich, A.L. Jakobsen and I.M. Mees (eds) Looking at Eyes. Eye-Tracking Studies of Reading and Translation Processing. (Copenhagen Studies in Language 36) (pp. 103–124). Copenhagen: Samfundslitteratur.

Just, M.A. and Carpenter, P.A. (1980) A theory of reading: From eye fixations to comprehension. Psychological Review 87, 329–354.

Kintsch, W. (1988) The role of knowledge in discourse comprehension: A construction-integration model. Psychological Review 95, 163–182.

Künzli, A. and Ehrensberger-Dow, M. (2011) Innovative subtitling. A reception study. In C. Alvstad, A. Hild and E. Tiselius (eds) Methods and Strategies of Process Research (pp. 187–200). Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

O’Brien, S. (2006) Eye-tracking and translation memory matches. Perspectives 14, 185–203.

Perego, E. (ed.) (2012) Eye-tracking in Audiovisual Translation. Rome: Aracne.

Rayner, K. (1998) Eye movements in reading and information processing: 20 years of research. Psychological Bulletin 124, 372–422.