Musée Picasso

Picasso’s Personal Collection (Floor 3)

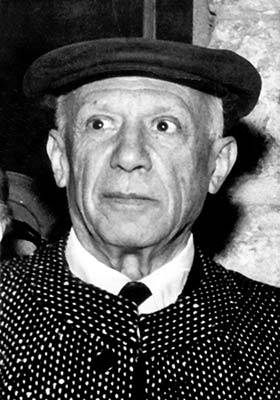

The 20th century’s most famous and—OK, I’ll say it—greatest artist was the master of many styles (Cubism, Surrealism, Expressionism, etc.) and of many media (painting, sculpture, prints, ceramics, and assemblages). Still, he could make anything he touched look unmistakably like “a Picasso.”

The Picasso Museum has roughly 400 of his works on display out of a revolving collection of about 2,000, showing the whole range of the artist’s long life and many styles. The women he loved and the global events he lived through appear in his canvases, filtered through his own emotional lens. You don’t have to admire Picasso’s lifestyle or like his modern painting style. But a visit here might make you appreciate the sheer vitality and creativity of this hardworking and unique man.

Rather than showcase its greatest hits for the tourist, the museum mixes it up twice a year for its local supporters who come back repeatedly. The ever-changing collection is laid out thematically, generally with no regard to chronology. Use this chapter as an overview of Picasso’s life and evolving styles, then explore this mansion of stimulating art from the creative mind of Picasso.

Cost: €14, covered by Museum Pass, free on first Sun of month. Timed-entry tickets are available online in advance but are unnecessary.

Hours: Tue-Fri 10:30-18:00, Sat-Sun from 9:30, closed Mon, last entry 45 minutes before closing.

Information: +33 1 42 71 25 21, www.museepicassoparis.fr.

Getting There: The museum is at 5 Rue de Thorigny, Mo: St-Sébastien-Froissart, St-Paul, or Chemin Vert (for location, see the Marais Walk map on here).

Tours: The museum has excellent posted information and an audioguide (€5, with two universal earbud jacks if you’d like to share it).

Length of This Tour: Allow one hour.

The ground floor is generally dedicated to temporary exhibits. Floors 1 and 2 are the core of the museum with selections from its permanent collection. Floor 3 always features paintings from Picasso’s personal collection—works of his that he never sold, and paintings by contemporaries (such as Miró, Matisse, Cézanne, and Braque) who inspired him. While this chapter is not intended as a room-by-room tour of this ever-changing museum, it does follow the general flow. Thankfully, the museum’s fine audioguide is updated with each change to the exhibit. Use this chapter to get the big picture, then explore.

Born in Spain, Picasso was the son of an art teacher. As a teenager, he quickly advanced beyond his teachers. He mastered camera-eye realism but also showed an empathy for the people he painted that was insightful beyond his years. (Unfortunately, the museum has few early works. Many doubters of Picasso’s genius warm to him somewhat after seeing his excellent draftsmanship and facility with oils from his youth.) As a teenager in Barcelona, he fell in with a bohemian crowd that mixed wine, women, and art.

In 1900, Picasso set out to make his mark in Paris, the undisputed world capital of culture. He rejected the surname his father had given him (Ruíz) and chose his mother’s instead, making it his distinctive one-word brand: Picasso.

The brash Spaniard quickly became a poor, homesick foreigner, absorbing the styles of many painters (especially Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec) while searching for his own artist’s voice. He found companionship among fellow freaks and outcasts on Butte Montmartre, painting jesters, circus performers, and garish cabarets. When his best friend committed suicide, Picasso plunged into a Blue Period, painting emaciated beggars, hard-eyed pimps, and himself, bundled up against the cold, with eyes all cried out (as seen in his Autoportrait, 1901).

In 1904, Picasso moved into his Bateau-Lavoir home/studio on Montmartre, got a steady girlfriend, and suddenly saw the world through rose-colored glasses (the Rose Period, though the museum has very few works from this time).

Only 25 years old, Picasso reinvented painting. Fascinated by the primitive power of African and Iberian tribal masks, he sketched human faces with simple outlines and almond eyes. Intrigued by the body of his girlfriend, Fernande Olivier, he sketched it from every angle (the museum has a few nude studies), then experimented with showing several different views on the same canvas.

The Picasso Museum has several of these primitive nudes. His friends were speechless over the bold new style, his enemies reviled it, and almost overnight, Picasso was famous.

Picasso went to the Louvre for a special exhibit on Cézanne, then returned to the Bateau-Lavoir to expand on Cézanne’s chunky style and geometric simplicity—oval-shaped heads, circular breasts, and diamond thighs. Picasso rejected traditional 3-D. Instead of painting, say, a distant hillside in dimmer tones than the trees in the bright foreground, Picasso did it all bright, making the foreground blend into the background and turning a scene into an abstract design. Modern art was being born.

With his next-door neighbor, Georges Braque, Picasso invented Cubism, a fragmented, “cube”-shaped style. He’d fracture a figure (such as the musician in Man with a Mandolin, 1911) into a barely recognizable jumble of facets, and facets within facets. Even empty space is composed of these “cubes,” all of them the same basic color, that weave together the background and foreground. Picasso sketches reality from every angle, then pastes it all together, a composite of different views. The monochrome color (mostly gray or brown) is less important than the experiments with putting the 3-D world on a 2-D canvas in a modern way.

Picasso didn’t stop there. His first stage had been so-called Analytic Cubism (1910-1913): breaking the world down into small facets, to “analyze” the subject from every angle. Now it was time to “synthesize” it back together with the real world (Synthetic Cubism). He created “constructions” that were essentially still-life paintings (a 2-D illusion) augmented with glued-on, real-life materials—wood, paper, rope, or chair caning (the real 3-D world). The contrast between real objects and painted objects makes it clear that while traditional painting is a mere illusion, art can be more substantial.

In a few short years, Picasso had turned painting in the direction it would go for the next 50 years.

Personally, Picasso’s life had fragmented into a series of relationships with women. In 1917, he met and married a graceful Russian dancer with the Ballet Russes, Olga Khokhlova (Portrait of Olga in an Armchair, 1917).

Soon he was a financially secure husband and father (see the portrait of his three-year-old son, Paul en Harlequin, 1924). After the disastrous Great War, Picasso took his family for summer vacations on the Riviera, where he painted peaceful scenes of women and children at the beach. He also moved from Montmartre to the Montparnasse neighborhood. (Over the years, Picasso had 13 different studios in Paris, mainly in Montmartre or Montparnasse.)

A trip to Rome inspired him to emulate the bulky mass of ancient statues, transforming them into plump but graceful women, with Olga’s round features. Picasso could create the illusion of a face or body bulging out from the canvas, like a cameo or classical bas-relief. Watching kids drawing in the sand with a stick, he tried drawing a figure without lifting the brush from the canvas.

In 1927, a middle-aged Picasso stopped a 17-year-old girl outside the Galeries Lafayette department store (by the Opéra Garnier) and said, “Mademoiselle, you have an interesting face. Can I paint it? I am Picasso.” She said, “Who?”

The two had little in common, but the unsophisticated Marie-Thérèse Walter and the short, balding artist developed a strange attraction to each other. Soon, Marie-Thérèse moved into the house next door to Picasso and his wife, and they began an awkward three-wheeled relationship. Worldly Olga was jealous, young Marie-Thérèse was insecure and clingy, and Picasso was a workaholic artist who faithfully chronicled the erotic/neurotic experience in canvases of twisted, screaming nudes.

Picasso lived almost all of his adult life in France, but he remained a Spaniard at heart, incorporating Spanish motifs into his work. Unrepentantly macho, he loved bullfights, seeing them as a metaphor for the timeless human interaction between the genders. Me bull, you horse, I gore you.

The Minotaur (a bull-headed man) symbolized man’s warring halves: half rational human (Freud’s superego) and half raging beast (the id). Picasso could be both tender and violent with women, thus playing out both sides of this love/war duality.

During the gray and sad years of World War II, Picasso stayed in Paris. His beloved mother had died, and he endured an endless, bitter divorce from Olga, all the while juggling his two longtime, feuding mistresses—as well as the occasional fling. With the end of the war, it was time for a change. He moved to the south of France. Sun! Color! Water! Spacious skies! Freedom!

Sixty-five-year-old Pablo Picasso was reborn, enjoying worldwide fame and the love of a beautiful 23-year-old painter named Françoise Gilot. She soon offered him a fresh start at fatherhood, giving birth to son Claude and daughter Paloma.

Picasso spent mornings swimming in the Mediterranean, days painting, evenings partying with friends, and late nights painting again, like a madman. Dressed in rolled-up white pants and a striped sailor’s shirt, bursting with pent-up creativity, he often cranked out more than a painting a day. Ever-restless Picasso had finally found his Garden of Eden and rediscovered his joie de vivre.

He palled around with Henri Matisse, his rival for the title of Century’s Greatest Painter. Occasionally they traded masterpieces, letting the other pick out his favorite for his own collection.

Picasso’s Riviera works set the tone for the rest of his life—sunny, lighthearted, childlike, experimenting in new media, and using motifs of the sea, Greek mythology (fauns, centaurs), and animals (birds, goats, and pregnant baboons). His childlike doves became an international symbol of peace. These joyous themes announce Picasso’s newfound freedom in a newly liberated France.

Picasso was fertile to the end, still painting with bright thick colors at age 91. With no living peers in the world of art, the great Picasso dialogued with dead masters, reworking paintings by Edouard Manet, Diego de Velázquez, and others. Oh yes, also in this period he met mistress number...um, whatever: 27-year-old Jacqueline Roque, whom he later married.

Throughout his long life, Picasso was intrigued by portraying people—always people, ignoring the background—conveying their features with a single curved line and their moods with colors. These last works have the humor and playfulness of someone much younger. It has been said of Picasso, “When he was a child, he painted like a man. When he was old, he painted like a child.”

In these rooms, you can get a glimpse of what Picasso treasured. There are works of his own—portraits of girlfriends, his kids, and himself—to which he may have had an emotional attachment. There are paintings by fellow painters who inspired him. As he traveled between his homes in Paris and the south of France, Picasso loved to decorate his studios with these paintings.

You may see works by Cézanne, whose rocky landscapes and chunky brushwork inspired Picasso’s Cubism. Renoir’s full-figured females inspired Picasso’s bathing women of the 1920s. Henri Rousseau’s work reminded Picasso of the power of childlike simplicity. Picasso collected African tribal masks, which influenced the primitive-looking faces of his early Cubist years. The paintings by Matisse are a reminder that, while the two men are often portrayed as archrivals, in fact they were good friends and neighbors who enjoyed exchanging paintings. You’ll see works by Picasso’s fellow Spaniards-in-exile like Miró, and his Surrealist buddies of the 1920s. Browsing the wide variety of different styles in these rooms, it becomes clear how Picasso incorporated these eclectic elements to become a master of many (other people’s) styles.