Marian Adams was laid to rest on a grassy slope in Rock Creek Cemetery, the oldest graveyard in Washington, D.C.1 According to family members, she was buried in a long willow or wicker basket covered with black cloth, a tradition of the William Sturgis family from which she descended. Most likely cut flowers were placed atop the basket before it was covered with dirt. Without a casket, Clover’s body could meld quickly with the earth—“ashes to ashes, dust to dust.”2 Shortly after her interment, Henry Adams ordered a modest “head stone,” costing $12, to mark the site temporarily while he considered options for erecting a more elaborate memorial at a later stage in his bereavement.3

These simple choices ran counter to the preponderant tradition in which most people were laid to rest in coffins, which were often placed in simpler “outer boxes” before burial to prevent dirt from filling in or marring the burial case.4 The word “casket” had more recently come into use, summoning up the idea of a jewel box. William Vanderbilt II’s body was placed in an elaborately constructed casket with silver handles and fittings. After that casket was inserted in its outer box, it was moved to a holding vault to await placement in a stone compartment in his family’s new Gothic-style mausoleum on Staten Island. According to newspaper reports, Vanderbilt had just gone to the cemetery with his son to inspect the construction work on the mausoleum a few days before his death.5 The completed structure features an altar and elaborate carvings. All of these preparations suggested his wealth, public stature, and concern about securing the grave from vandalism as well as his Christian beliefs about resurrection.

In the early 1880s, societies promoting cremation as a burial option had been organized in a number of cities. The societies offered lectures and publications, but this form of interment still met considerable religious opposition; in early 1884 only one crematory was reported to exist in the United States. Advocacy for cremation began to gain strength, however, at the end of the century.6

No matter which choice survivors made, the physical body was the center of initial mourning rituals, at the funeral and burial. Ministers might call it the departed person’s “house in clay,” a shell now abandoned by his or her soul, but the lifeless form remained the unique affective center. Although hidden within its funeral case, it was a real presence around which emotion coiled, along with a dutiful respect and, for some, a certain repugnance and almost superstitious dread. The corpse, it seemed, needed to be both venerated and propitiated at this crucial moment. For most, an empathic encounter with the body could not help but inspire self-reflection on the brevity of all human existence and on its significance.7

After the early stages of trauma for survivors and deep mourning, which involved the multiple decisions related to funeral services and interment, the cemetery itself became an important meeting ground with the dead in the weeks and years ahead, a place where the spirits of the deceased seemed for at least a time to cohabit the earth. The cemetery, properly landscaped and ornamented, could offer an aesthetic, sensory envelope of space for this potential crossing of revenants and living. The tombstone or monument placed above the grave provided something concrete and specific for the senses to perceive, a visual and tactile trace that could be physically encountered and even touched—that was not a phantom spirit. As the years passed, these markers, standing in for the harsh reality of the moldering body below, remained as silent witnesses to the interconnection of generations, something real and phenomenologically different from verbal recollections. They invoked the continuing presence of the dead (a subtext usually repressed in daily life) while at the same time confirming that they had departed their earthly community forever.8

Darkened skies, wind, and a miserable, driving rain marked the day set for Marian Adams’s interment, according to a written recollection left by her brother-in-law Charles Francis Adams.9 But sister Ellen Gurney dwelled instead on the constant natural beauty of the surrounding landscape in a letter to a friend, reassuring her that Marian’s grave was located “in a most peaceful church yard … with room for us all if we wish it … a place which they often went to together and where the spring comes early.”10 Henry and Clover had indeed visited this graveyard, where some of his distant relations rested, a number of times. In December 1878, for example, Clover wrote her father about a Hamlet-like experience they had in the “beautiful” old cemetery: “a curious chat with a handsome gay old grave digger” they met who regaled them with his life story.11 They had also toured Civil War cemeteries such as Arlington Cemetery across the Potomac River, seeing them as sites of communication with nature and the universal, history, and respectful familial reverence. “We rode to Arlington Friday P.M. and it was lovely with its fifteen thousand quiet sleepers,” Clover wrote her father in 1882.12 They were only too familiar as well with the first garden cemetery in America, Mount Auburn Cemetery near Boston, which influenced the development of all future graveyards.

Henry Adams’s role in making an imprint on the U.S. cemetery landscape seemed almost foreordained by these experiences and a string of earlier events. He had been delivered into this world by Jacob Bigelow, who was the doctor to Boston’s most elite residents but is now best remembered as a founder of Mount Auburn Cemetery. “I was roused at three o’clock this morning by my wife who soon gave indications of the necessity of Dr. Bigelow’s presence,” Charles Francis Adams wrote, describing his son Henry’s birth in his diary entry for February 16, 1838. “I accordingly went for him in the midst of a snow storm and in the extraordinary silence of the streets.”13

Bigelow and other leading citizens in Boston had opened Mount Auburn Cemetery in Cambridge seven years earlier, in 1831, in response to growing concerns about health hazards from graveyards located in city centers. They adopted new European ideas about using the cemetery as a romantic landscape of memory and moral and historical instruction, a place where the body could decay in the embrace of God-given natural beauty and visitors could be instructed about their ancestors.14 Clover’s grandfather William Sturgis (1782–1863), a sea captain and wealthy merchant, had been among a dozen influential Bostonians who joined Bigelow in launching plans for its creation, and Sturgis also was among the first Bostonians to acquire a family lot there.15 The Bigelows and Sturgises intermarried, and Clover’s close relations included a Bigelow cousin. Henry Adams became familiar with Mount Auburn from excursions in his boyhood and significant visits in his adulthood. His father described after-dinner strolls in the cemetery in his diary during the years of Henry’s childhood. Later, the Sturgis family lot was the place where Henry joined Clover in witnessing Dr. Hooper’s burial beside her mother’s grave. It was the hillside resting place as well for many of Clover’s other relatives.

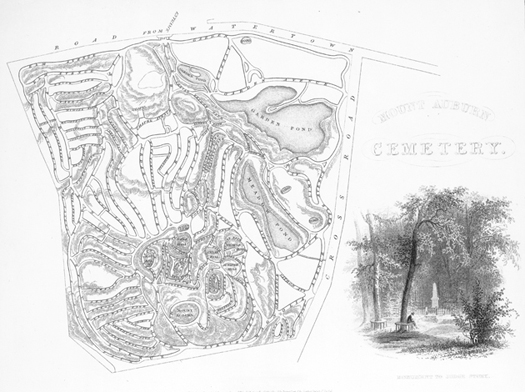

Modeled after the famous Père Lachaise Cemetery in Paris and also influenced by English garden theories and U.S. horticultural interests, Mount Auburn represented a new kind of graveyard for America. Removed from the city center, it featured serpentine walks, ponds, and scenic views amid evergreens and ornamental trees (Figure 22). In this natural park families could buy large plots to bury their dead together and could control the way these plots were decorated, landscaped, and bounded with railings, with an expectation of permanence. Mount Auburn quickly became the prototype for scores of rural garden cemeteries opened across America in the 1830s and 1840s, including Laurel Hill in Philadelphia, Green Mount in Baltimore, and Green-Wood in Brooklyn. By midcentury these nonsectarian cemeteries existed in most cities, replacing or superseding crowded urban graveyards.16 Rock Creek Cemetery in Washington, which had been established much earlier, about 1719, slowly adopted many of the aesthetic principles of the picturesque new garden cemeteries and eventually became a nonsectarian site, chartered by Congress as a public cemetery in 1871.

Leaving behind the slate slabs with winged skulls of earlier times, most of the monuments of the 1830s and 1840s were three-dimensional marble structures, frequently obelisks or sarcophagi, broken columns and flaming or draped urns placed atop pedestals. These symbols drew on classicizing, Egyptian, and sometimes Gothic sources suggesting the continuity of civilizations and the permanence of memory after life itself is interrupted. They were visual euphemisms for death, adopted at the same time that the graveyard was renamed the “cemetery”—from the Greek word for sleeping place—and that death itself was relabeled “passing on.” Monuments at Mount Auburn and elsewhere also often glorified the centrality of family relations. Epitaphs describe women and children in terms of a patriarchal system of family relations—“Beloved Mother,” “Beloved Father”—and suggest the chain of generations that survives when one life is snuffed out. Life dates were almost always included as a matter of family record. In addition to portrait statues and stone angels, neoclassical women mourners and sentimental allegorical figures of Faith, Hope, Charity, and Memory, with wreath, book, or flowers, were the most frequently seen figurative works.17 Period prints showed parents leading children to cemetery monuments and discussing the lessons contained in them and in the natural setting of the rural cemetery.

Figure 22.

James Smillie, Mount Auburn Cemetery—Monument to Judge Story [and map of the cemetery, Boston, Mass.], ca. 1848. Engraving. Frontispiece, Mount Auburn Cemetery Illustrated. Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress, Reproduction number LC-USZ62-91748.

William Wetmore Story’s father, Associate Supreme Court Justice Joseph Story, delivered the consecration address at the opening of Mount Auburn Cemetery. Story, who had recently lost a ten-year-old daughter to scarlet fever, spoke movingly of the consoling impact of the natural space, saying, “All around us there breathes a solemn calm, as if we were in the bosom of a wilderness, broken only by a breeze as it murmurs through the tops of the forest.… Ascend but a few steps and what a change of scenery to surprise and delight us.” Visitors, he concluded, return to the world feeling “purer, and better, and wiser, from this communion with the dead.”18

In the hushed silence, with only the sounds of trees rustling and birds singing and the touch of a breeze on one’s face, a stroller could contemplate higher thoughts, large and moral thoughts. The visitor walking through the funerary arena could also experience the natural space as a series of images and sensations, much as a person processes a filmic array of impressions crossing a bridge. These change with proximity and distance, the seasons and time of day, dampness, chill, and warmth. Philosophers such as Edward Casey have talked about how each visit to a site of experience, such as a cemetery, is a unique event. The living, moving body is the vehicle and agent of this specific “emplaced experience” as it passes through the landscape.19 The pilgrim to a cemetery might sense that this is a special place where the survivor’s spirit seems closer to an authentic consciousness of life and God and yet-unknown universal forces. It could lift the visitor to a fleeting glimpse of a state of being beyond what we can see with our eyes or touch with our hands.

Jacob Bigelow understood these ideas and sought to add further elements of mystery and difference. A minister’s son who aspired to be a true enlightenment intellectual, he could cite Herodotus and Pliny as well as William Cullen Bryant’s “Thanatopsis,” and, when not practicing medicine, he wrote about art and landscape design, botany and technology. He used architectural symbolism to impose his taste and philosophical ideas on Mount Auburn’s forested landscape. For instance, the Egyptian revival gate he designed, first built in wood in 1832, signaled to visitors that they were entering a realm of the dead akin to the ancient pyramids—an eternal domain beyond the normal powers of reason. The gate became the emblem of Mount Auburn.20 The large stone sphinx memorial that Bigelow later commissioned from Martin Milmore and his brothers continued this theme. While early Civil War monuments were often erected in cemeteries in the American North and South, Bigelow sought something different than a soldier monument. He was well aware that the figure of a sphinx summoned up multiple associations. Egyptian and Greek in its most ancient origins, it had also functioned as picturesque garden sculpture in places like Versailles and Blenheim Palace in England.21 Along with the Egyptian gate, it raised the notion that wonder and ancient mystery—along with recorded life dates, religious certainties, and family relations—had a distinctive place in the American cemetery. It promoted the suspicion that past, present, and future come together most clearly in the cemetery, a sanctuary where nature and unusual monuments with enduring associations intensified sensory perceptions.

By the time of Clover Adams’s suicide, William Vanderbilt’s collapse on the floor of his Fifth Avenue home, and the deaths of the Milmore brothers, Mount Auburn and the other garden cemeteries it had influenced had been transformed by the eclectic wishes of their lot owners. They had lost much of their natural wilderness qualities. Competition among lot owners jeopardized the founders’ original goals for picturesque beauty. Families often built fences, or “grave guards,” around their lots or landscaped them to their own liking. Different heights and styles of monuments were erected over the years, often several within one family lot, creating a disharmonious mishmash (Figure 23). At the same time, cemeteries acted as early parks and became popular enough that rules had to be posted to restrain picnicking and rowdy or irregular behavior that disrupted the desired calm. “Visitors are requested to keep on the walks, and not to pluck flowers or shrubs, or to injure the trees,” noted the early rules of Laurel Hill Cemetery, which also forebade dogs and saddle horses.22

Figure 23.

Profusion, of monuments in Mount Auburn Cemetery of many sizes and styles. Photo by Frank J. Conahan.

Although the founders had counseled modesty, regulations had to be issued to maintain a naturalistic setting. Many cemeteries set height limits, as columns and obelisks grew taller and taller, with more stone apparently signaling more wealth and virtue for some survivors or patrons. In the postwar years certainly, the oldest styles of tombstones had become the subject of ridicule and doggerel in newspapers and even on the theatrical stage. Stories about famous people’s grave monuments were common in newspapers, which regularly carried “tombstone” oddities, silly epitaphs, and short stories about grave markers for favored pets and legal disputes. Commercial monument dealers often were blamed for encouraging this profusion of monuments, as they promoted sentimental symbols, fussy details, higher and higher obelisks, and clashing styles in their relentless drive for profit.

As scholar Karen Halttunen has noted, the “full emergence of the cult of mourning that distinguished nineteenth-century views of death had occurred in the rural cemetery movement of the 1830s.” Now the new national military cemeteries, such as Arlington near Washington, D.C., that were created during and after the Civil War reinforced the same retreat from romantic sentimentality that was seen in mourning mores, funeral rites, and literature. In their orderly grandeur, the military graveyards also added to an impetus for a new order and simplification of the cemetery landscape.23

Marian Adams, having lost her cousin Robert Gould Shaw and other acquaintances in the war, was an astute observer of these new forms of postwar memorialization. The sheer numbers and simplicity of the rows of uniform military grave markers placed on the grassy slopes of Arlington Cemetery moved her deeply. She memorialized a visit she and her husband made to Arlington in mid-November 1883 by taking a photograph (Figure 24). A warped print of this picture preserved in the Massachusetts Historical Society appears slightly unfocused, but it is clear that Adams found beauty in the enforced sameness of the soldiers’ monuments spread across the field and the leaves still clinging to the trees before winter set in. For her, the grave markers were not emotionally sterile allegories; in their lack of ornament they were proximate to the innocence and purity of youth and nature. On this print, she wrote in the margin, “Ich gehe durch dem Todeschlaf / Zu Gott ein als soldat und Crau.” That phrase is a quotation from Goethe’s Faust in which a soldier speaks to his sister about honor and then dies, telling her, “Now through the slumber of the grave I go to God, a soldier brave.”24

Sculptor Augustus Saint-Gaudens, who would design the Adams Memorial, took a special interest in the funerary landscape in his later years and especially singled out for praise the “extraordinary dignity, impressiveness and nobility” of the cemetery at the U.S. Soldiers’ Home opposite Rock Creek Cemetery, with its neat rows of vertical markers. Its aesthetic was attained not by an eclectic array of large monuments, he noted, but “by the very simplicity and uniformity of the whole.” He urged that open areas of Arlington be similarly undisturbed by “the invasion of monuments which utterly annihilate the sense of beauty and repose.”25

Figure 24.

“Arlington National Cemetery.” Photograph by Marian Hooper Adams, November 5, 1883. From the Marian Hooper Adams Photographs. Photograph number 50.94. Courtesy of the Massachusetts Historical Society.

After the Civil War, cemetery superintendents across the country began taking steps to attain long, sweeping vistas with fewer and more tasteful large monuments and lower profiles for all but one central family monument on each lot. A new, landscape-lawn aesthetic for cemeteries had emerged most influentially at Spring Grove Cemetery in Cincinnati, where it was pioneered by landscape designer Adolph Strauch in the late 1850s and early 1860s. Now, in the ideal plan, monuments were to be subordinated to “broad and unbroken” landscape vistas (Figure 25). A natural appearance was emphasized and too tall, vertical monuments were discouraged in an attempt to create a unified aesthetic in which all could share.26 These ideas were rapidly adopted elsewhere. In Woodlawn Cemetery in New York, for instance, founded on a rural cemetery model, lots were proposed on the new landscape-lawn model by the late 1860s, within a few years of its opening. Strauch’s words opposing the tasteless “multiplication of monuments” were cited in annual reports to Woodlawn lot owners by managers who had traveled to Cincinnati to study his efforts: “People have lots, they have money, they must do something, and they unfortunately have not that taste which leads them to find their gratification in a consistent whole, rather than in the ornamentation of a particular spot,” wrote Strauch. “They … produce effects that people of cultivation regret.… Those who have monuments to erect, should wait until they can avail themselves of the advice of persons of taste, and thereby make a real addition to the attractions of a place, in whose beauty so many have an interest.”27

Figure 25.

Landscape-Lawn vista. View of Spring Grove Cemetery, Cincinnati, ca. 1890. Cincinnati Museum Center.

Cemetery managers insisted on greater central control over placement and choice of monuments, enforcing a more harmonious vision for the resting place of the dead via new regulations and launching an era of reform (Figure 26). The tangled, winding, woodsy paths of garden cemeteries were abandoned for more rounded, flowing lines and fields of grass, height limitations for monuments were adopted, and fences and hedges surrounding lots were stripped away in many cemeteries.28 Family control over individual plots was restricted. Lot owners were encouraged to install only one tasteful and “artistic” family monument per lot (and preferably not a tall obelisk). If families felt it necessary to mark the position of each body as well, they were encouraged to do so with small granite “footstones” resting flush with the ground or projecting just a few inches above it. These were stable and easily maintained, unlike tall, thin slabs of stone, which broke or tipped over more easily. Strauch encouragingly pointed out the example of the “late Duke of Saxe-Gotha” who had directed that his only monument be a tree planted on his grave.29

Figure 26.

“Swan Song of Some Dead Types of Monuments,” Monumental News 27, no. 2 (February 1915).

Severe limitations on monument inscriptions were also favored, in contrast to the sometimes lengthy, highly personalized quotations marking earlier American graves. “Epitaphs should be plain and simple,” Strauch said.30 Turn-of-the-century cemetery managers preferred that family monuments bear only the family name and that individual markers carry only name or initials, birth and death dates. The restricted inscriptions on turn-of-the-century cemetery monuments stood in stark contrast to the earlier emphasis on kinship and patriarchal family structure on cemetery memorials. Leaving behind terms like Mother, Sister, Daughter, or Father, the new forms reflected a shift in gender spheres and family relations amid industrialization, advances in transportation, and greater social mobility.31

All in all, fewer, lower, simpler, more uniform markers were encouraged, fitting within a more open expanse of land. Old styles lingered, as they do today. But many cemeteries began setting aside large areas in which only markers resting flat to the ground were allowed. The Association of American Cemetery Superintendents, an influential trade association founded in 1887, pushed hard to let gently varied meadowlands be the new iconography of memorialization.32 Bellett Lawson, president of the association, summed up members’ attitudes in a speech in 1902 in which he declared: “I am fully aware that the time has not arrived when a total abandonment of monuments can be advocated, desirable as it may be, but I do think that more stringent and compulsory measures might be adopted to educate the public to subordinate personal desire and individual taste to dictation and advice of cemetery managers.”33 As tasteful accents to the whole, some cemeteries encouraged naturalistic monuments, such as tree trunks carved out of limestone or living trees or the occasional large boulder bearing a tablet inscribed with the family name. Art critic Mariana Van Rensselaer commented that a boulder, with much of its surface left moss-grown or ivy-covered, “is a simple, serious, dignified and artistic monument, worthy of the noblest dead.”34

Ideas developed in the aesthetic movement and fine-arts realms ultimately worked their way into the domain of the cemetery, and a scattering of high-style monuments was welcomed, the effect of which would, in theory at least, benefit all. They appeared at a time when public monuments also blossomed on city squares, and refined pedagogical murals were installed in public buildings amid the turn-of-the-century City Beautiful movement. In the landscape-lawn aesthetic, cemetery officials accepted the occasional heroic-sized figurative monument—especially when it was located on a larger-than-usual plot of land and made by a fine artist for a great man—as a tasteful landmark that could grace the whole harmonious environment. Great memorial art could now be equated with great ideal art.

By the beginning of the twentieth century, cemetery sculpture could also be a place for a community of mourners and admirers to contemplate life’s meaning without offering explicit consolation or promises of rebirth. It no longer was required to stress overt, didactic praise about the dead one being the exemplar of the good man, or to focus, Victorian style, on personal details. Evocative rather than descriptive techniques were adopted to suggest a reality beyond earthly relationships.35

The changes in cemetery design originally were hailed as democratizing (Mount Auburn had been formed as a private association of families and individuals), yet a chasm continued to exist in death between educated, wealthy, Euro-American Protestants and members of other faiths, races, and ethnic and income groups.36 Cemeteries frequently featured socially stratified zones, like the best streets on which the wealthy lived, in the late nineteenth century. Some complained that the new landscape aesthetic provided another spur for the rich to flaunt their wealth. J. H. Griffith, who wrote in Monumental News in 1902, for example, argued that the landscape-lawn plan “encourages wealthy lot owners to erect costly memorials because of the better opportunity of their showing off to advantage amid unobtrusive and artistic surroundings.”37 But other points of view prevailed.

“For the present, it is fortunate for all that wealth insures many large lots in cemeteries, thus securing a proportion of comparatively open space,” Fanny Copley Seavey told a convention of cemetery officials in St. Louis in 1896.38 She envisioned a “cemetery of the future” in which all classes of Americans could share equally in the open lawns. In that ideal cemetery, however, she said, such works of sculptural art as Daniel Chester French’s Milmore Memorial “and kindred dreams of beauty will readily be given a suitable setting because they will never be too numerous and are in harmony with the atmosphere of these landscape homes of the dead.”39

Mariana Van Rensselaer, whose writing was admired by a prestigious circle of sculptors, painters, and architects, including Saint-Gaudens (who sculpted a bas-relief portrait of Van Rensselaer), also urged fewer, better monuments in cemeteries in her Art Out-of-Doors, declaring: “Owners should be encouraged to make their monuments, not merely as artistic, but also as simple and unobtrusive, as possible. Only a great man, one to whose grave strangers are likely to come as pilgrims, is entitled to a conspicuous tomb. Even he does not require it.”40 She called for more active involvement of fine artists in cemetery commemoration, which had been largely the province of monument dealers and associated stone quarries:

If, in … telling other people that we loved our dead, we could consent to speak less loudly and more carefully, how beautiful, how touching and impressive a cemetery might be! The price now paid for a big monument, bad in design and worse in ornamentation, might persuade even a great artist to design a cross or head-stone which, in its simple way, would be an object of the utmost value. Such an object would really honor the memory of our dead, instead of simply shouting out their names with a crude and vulgar voice; and the association of many such would make our cemeteries really beautiful spots.41

Cemetery officials agreed, demanding that where there was statuary in the graveyard, it should “keep pace with the progress which is shown in the other branches of the sculptor’s craft.”42 Good design was sought to contribute to a unified, therapeutic environment that would aid the contemplation and recuperation of mourners. Design was regarded as another agent of human improvement, another marker of progress in the domain of the cemetery.43 But it was still clear that the upper class could buy a greater degree of individual identity in the graveyard, as elsewhere, than denizens of the lower classes. A social chasm continued in death as in life.

Plate 1.

Augustus Saint-Gaudens, The Adams Memorial, 1891. Rock Creek Cemetery, Washington, D.C. Photo by Cynthia Mills.

Plate 2.

Daniel Chester French, The Milmore Memorial (The Angel of Death Staying the Hand of the Sculptor), 1892. Forest Hills Cemetery, Boston. Photo by Cynthia Mills.

Plate 3.

Frank Duveneck, Tomb Effigy of Elizabeth Boott Duveneck. Bronze and gold leaf, cast in 1927 for the Metropolitan Museum after the artist’s 1891 design for the Cimitero Evangelico degli Allori, Florence, Italy. Image copyright © The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Image source: Art Resource, NY.

Plate 4.

William Wetmore Story, Angel of Grief Weeping Bitterly over the Dismantled Altar of His Life, 1894. Protestant Cemetery, Rome. Photo by Sean McCormally.

Plate 5.

Martin Milmore, Coppenhagen Monument, 1874. Mount Auburn Cemetery, Cambridge, Massachusetts. Photo by Frank J. Conahan.

Plate 6.

Frank Duveneck, Elizabeth Boott Duveneck. Cincinnati Art Museum, Gift of the Artist, 1915.78.

Plate 7.

Augustus Saint-Gaudens, Hamilton Fish Memorial, 1892. St. Philip’s Churchyard, Garrison, New York. Photo by Anthony Badalamenti.

Plate 8.

Karl Bitter, Hubbard Memorial, 1902. Green Mount Cemetery, Montpelier, Vermont. Photo by Sean McCormally.