The projections are that this virus will kill one million Americans in 1976.49

The writer John Barry has characterized the 1918 pandemic as the “first great collision between nature and modern science.”50 Certainly it was a supreme test of the self-confidence that scientific medicine had acquired in the generation following the epochal discoveries of Pasteur and Koch. Many of history’s great killers—cholera, rabies, typhoid, anthrax, diphtheria, tuberculosis, even plague—had been successfully unmasked as species of bacteria; and although no one had yet seen one, viruses had been recognized in concept as the cause of polio and other diseases. In the Caribbean U.S. Army doctors had driven back the legendary scourge of yellow fever. Potent vaccines and antitoxins had been developed, and biochemistry had taken giant steps; and in the great hospitals and laboratories of Berlin, London, Paris, New York, and Baltimore, all the foundations seemingly had been laid for the defeat of infectious disease.

In addition, World War I mobilized an unprecedented medical effort. As Barry emphasizes, the world’s top researchers all anticipated that the Great War would unleash a major epidemic of some kind. But no one anticipated that it would be influenza; indeed, before 1918 flu was not considered a serious killer. Global outbreaks in 1889 and 1898 had, to be sure, raised mortality, but scarcely on the scale of the bubonic plague pandemic of 1894–1918 which ultimately killed millions and briefly threatened to cause the collapse of world commerce. Under grim wartime conditions, with millions of soldiers mired in the mud and filth of trench warfare or overcrowded in squalid hospitals and training camps, pneumonia was a grave danger, but influenza was considered to be merely one of its several causes, along with measles.

In the winter of 1916–17, the British Army experienced a vexing outbreak of acute pneumonia that was accompanied by heliotrope cyanosis—the victims’ faces turned blue as their lungs drowned in blood—at its huge encampment at Etaples in France. British researchers have recently proposed that this incident was the first “seeding” of the influenza subtype that became pandemic in the summer of 1918. Army doctors at the time, however, diagnosed the outbreak as epidemic bronchitis and were shocked when the same terrifying symptoms returned on an epic scale with clearly identifiable influenza eighteen months later.51

Barry’s much-praised book, The Great Influenza, provides a gripping account of the desperate campaign mounted by America’s leading pulmonary specialists and epidemiologists to contain the disease as the new plague sowed death and panic in the early fall of 1918. Like their European counterparts, they never came close to identifying the true pathogen or creating an effective vaccine, so in the end, public-health officials everywhere fought influenza with the same ancient weapons that Renaissance city-states had used to resist bubonic plague: quarantines and face masks. In a few exceptional cases—American Samoa and Australia—draconian quarantines excluded the pandemic or at least delayed its arrival until its virulence had subsided. Elsewhere the influenza firestorm raged on until it had simply burnt up all available human fuel. With some 500 million people estimated to have been infected, the pandemic was modern medicine’s greatest defeat.

But science does not celebrate defeat. Because the self-image of twentieth-century medicine is organized around a heroic mythology of progressive victory against disease, the 1918 catastrophe—that “great shadow cast upon the medical profession”—was quickly repressed in popular memory.52 After a final flare-up of virulence in winter 1919, the pandemic died away, and influenza research then lost its global urgency. Unlike previous plagues that had laid siege to society for years or decades on end, the great influenza—in essence, a viral atomic bomb—did most of its killing in a single season. Many at the time thought (and some still think today) that it was an unrepeatable aberration, part of the larger nightmare ecology of 1914–18. The pandemic’s mystery persisted, however, and a small but committed cadre of microbiologists soldiered on in their laboratories. By the late 1920s they had discarded the once-orthodox belief in a bacterial pathogen and had begun to look for an influenza virus. A swine variety was isolated in 1930 and, using ferrets as surrogates, its human counterpart was identified during a London flu epidemic three years later; both were believed to be offspring of the 1918 killer, with today’s opinion favoring the idea that humans passed the virus to pigs, rather than vice-versa.53

After Pearl Harbor, Washington again began to worry about influenza. The senior officers in the surgeon general’s office had been young doctors on the frontlines of the 1918 pandemic, and they were haunted by the threat of another pandemic in the barracks. A renowned University of Michigan researcher, Dr. Thomas Francis, who had discovered influenza A’s antigenic diversity in 1936 and isolated influenza B in 1940, was appointed head of the Influenza Commission, and his young protégé, Jonas Salk, was charged with carrying out vaccine field trials in 1943. Within a year, a safe and effective experimental vaccine using inactivated viruses grown in fertile eggs was dispelling (forever, some thought) the specter of 1918.54 However, in the winter of 1946–47, the Francis/Salk vaccine (based on 1934 and 1943 strains) totally failed to provide protection against a new flu. Although the 1947 outbreak (a “pseudo-pandemic”) infected hundreds of millions across the globe, it fortunately lacked pandemic lethality; current opinion is that the absence of any cross-immunity between earlier strains and the 1947 flu probably represented an extreme case of mutation within a subtype (H1N1) which otherwise preserved the basic surface antigen (HA and NA) characteristics of 1918.55

The 1946–47 failure demonstrated the need to annually update vaccine composition based on careful international screening for newly emergent strains. The new World Health Organization was spurred to establish a world influenza center under the leadership of the famous flu researcher Sir Christopher Andrewes at the British National Institute for Medical Research (NIMR) at Mill Hill, London; this became the cornerstone of today’s global influenza surveillance system. Affiliated national laboratories send unknown influenza strains to London (or now, to Atlanta, Melbourne, or Tokyo) for rapid identification. Based on worldwide reports, the WHO laboratories then provide drug manufacturers with candidate strains for the next season’s flu vaccine. This system faced its first great test in 1957 when a new flu emerged in the southeastern Chinese province of Yunnan (also the likely origin of the 1894 plague pandemic). Because air travel was still a relatively uncommon mode of transportation, the virus spread by traditional overland routes, via Russia to Europe, and by sea to the Western Hemisphere. Unlike the 1946–47 virus, this was not a mutation of the 1918 strain, but a genuine reassortant—probably arising in pigs—with avian surface proteins (HA and NA) and human-flu internal proteins. H2N2—as it was later classified—was, in other words, a new pandemic influenza.

In the United States, the Eisenhower administration rebuffed appeals from public-health experts for a mass vaccination campaign. Although the surgeon general did appropriate small sums for influenza surveillance, the Republicans in power relied upon free enterprise to develop and distribute the vaccine. “The official national public policy at that time,” writes Gerald Pyle, “was that the private sector—[drug producers], physicians and hospitals—could easily deal with the problem.”56 But in the case of influenza, without government coordination classical supply-and-demand relationships work mischievously. The vaccine needs to be produced in quantity for immunization at least a month before the peak of an epidemic, but most of the market demand from individual consumers comes only after the epidemic is in full course. Thus the pharmaceutical industry in fall 1957 was, according to J. Donald Miller and June Osborne, “too little and too late. By mid-October of 1957, when the epidemic reached its peak, less than 30 million doses of influenza vaccine had been fully tested for release, and only 7 million persons had actually received the benefit of immunization.”57

Fortunately, the Asian flu seldom produced the viral pneumonia, cyanosis, and acute respiratory distress that so gruesomely killed off young adult victims in 1918. An arsenal of powerful new antibiotics, moreover, gave doctors unprecedented control over secondary bacterial infections. Still, 2 million people worldwide were later estimated to have perished in the pandemic, including 80,000 Americans, many of whom might have been saved by timely vaccination.58 In the opinion of public-health veterans, these deaths were the dismal price of the failure of Eisenhower’s reliance upon the invisible hand of private enterprise to do the work of government.59

Eleven years later a third pandemic strain was isolated in Hong Kong, although it likely had its origins in neighboring Guangdong. This reassortant, again probably originating inside a pig, conserved the 1957 NA but added a new duck HA (thus becoming H3N2). It was fabulously contagious (500,000 cases in Hong Kong in a few weeks), but unexpectedly mild-mannered, probably because of widespread cross-immunity to its familiar NA. Like an aging rock band on a revival tour, the Hong Kong flu (H3N2) carefully retraced the itinerary of the 1957 Asian flu (H2N2), although its progress was now accelerated by air travel—GIs returning from Vietnam promptly brought it back to California in September 1968. The drug companies again failed to deliver the vaccine in time. “At the peak of the epidemic,” write Miller and Osborne, “only 10 million doses of vaccine had been distributed and no more than 6 million individuals had been protected; again, a large store of unused vaccine remained after the epidemic had passed.” If H3N2 had been more virulent, a catastrophe might have resulted. About 34,000 Americans died in the event, as did 700,000 others across the world.60

The Hong Kong flu left an ambiguous legacy. For many politicians and nonspecialists in the medical community, the relatively mild outcome relaxed apprehensions about pandemic influenza. “[M]any health-policy makers,” writes Pyle, “felt no need for an inoculation program.”61 Moreover, the generation of doctors who had experienced the pandemic of 1918 were retiring from research, and new medical school students inherited little more than folklore about hyperlethal influenza strains—and vaccines and antibiotics seemed to be holding an old monster firmly in check. This false sense of security was reinforced by scientific ignorance: despite some important breakthroughs, such as the technique of negative staining that allowed influenza viruses to be photographed under an electron microscope, surprisingly little new ground had been gained in understanding the molecular chemistry of infection or the evolution of the influenza genome. “It was unsuspected [for example] that influenza viruses from animals and birds are involved in the origin of pandemic strains of influenza.”62

Influenza specialists, however, took away different lessons from the 1957 and 1968 experiences. They were appalled by the unnecessary loss of life and the inefficiency of the profit-driven vaccine marketplace. Pharmaceutical corporations manufactured too little vaccine, and most of it failed to reach such key vulnerable groups like elderly people, pregnant women, and asthmatics. “In 1975, for example,” Miller and Osborne write, “less than 20 percent of the group for whom the vaccine was recommended were actually immunized; much of the remaining vaccine had gone to corporations which purchased flu vaccine in bulk and administered it to their young, healthy employees to reduce wintertime attrition due to the flu.” The influenza fighters, in contrast, argued for a federally-supported vaccination program for the country’s high-risk population, as well as lobbying for a much more timely and aggressive Washington response to the next pandemic.63

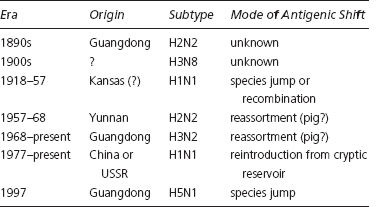

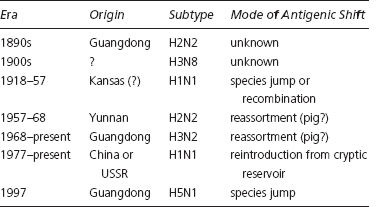

New discoveries soon supported the case for taking influenza more seriously. After 1968, researchers made a number of dramatic breakthroughs. Virologists, for the first time, were actually able to see the distinctive shapes of the HA and NA molecules. They also confirmed that antigenic drift was the result of point mutation (amino acid substitution) and that HA and NA mutated independently. Even more importantly, they identified genetic reassortment as the probable mechanism for the emergence of new pandemic subtypes; with the parallel discovery of influenza’s natural home in ducks and waterfowl, researchers could begin to trace the virus’s modern family tree (see Table 3.1). They ultimately identified 15 antigenically distinctive HAs and 9 different NAs in the avian reservoir, for a total of 135 hypothetical subtypes. The evolution of human influenza, it was now clear, was primarily driven by the crossing over of new HA proteins from waterfowl—after its deadly debut, each pandemic form then settled down to earn its living by modest mutation. Blood sera studies of the 1957 and 1968 pandemics, moreover, indicated that elderly people had some immunity to the new pandemic HAs. Researchers, accordingly, postulated that an H2 subtype had caused the 1889 pandemic, and an H3 the 1898 pandemic. Their reemergence in the postwar period was interpreted as evidence that influenza had hiding places or cryptic reservoirs where it could slumber for decades, or even generations.64

Table 3.1.

Influenza A Dynasties

The vistas opened by influenza research in the 1970s were breathtaking, but new knowledge only seemed to deepen the fundamental mysteries. The molecular basis of flu virulence remained unknown, as did the viral component responsible for catastrophic cyanosis. No one could convincingly explain why new subtypes usually extinguished the old, or how seemingly extinct lineages could suddenly reemerge, nor could researchers predict which avian hemagglutinin (an H5 or H7, for example) would next cross the species barrier. Some believed that only a few HAs were endowed with the ability to successfully reassort with human flu genes, while others conjectured that all avian HAs were potential new human influenzas. There was broad agreement, however, that medicine needed to heed influenza’s unpredictable evolutionary potential. The revelation of an unexpectedly diverse wild gene pool implied that 1918 might not have been such an aberration after all.

On 13 February 1976, the New York Times carried an op-ed piece by Dr. Edwin Kilbourne, a leader of the younger generation of influenza researchers. Kilbourne warned that a new pandemic might be close at hand: “Worldwide epidemics, or pandemics, of influenza have marked the end of every decade since the 1940s—at intervals of exactly eleven years—1946, 1957, 1968. A perhaps simplistic reading of this immediate past tells us that 11 plus 1968 is 1979, and urgently suggests that those concerned with public health had best plan without further delay for an imminent natural disaster.” The very same day, communicable-disease officials at the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) in Atlanta were discussing disturbing laboratory findings. New Jersey public health officials had sent the CDC cultures of an unidentified flu that had killed one Army recruit and hospitalized several others at Fort Dix; Dr. Walter Dowdle, the director of CDC’s lab, now reported that the mysterious virus was swine flu, a variant of H1N1 that was believed to be genetically closer to the original pandemic strain than the attenuated human genotypes that had circulated from 1920 until they were replaced by H2N2 in 1957. In the worst-case scenario, the great killer of 1918 had been resurrected and posed acute danger to anyone born after 1956 (who thus lacked H1N1 immune memory).65

CDC Director David Sencer canvassed the opinions of other experts, but the crucial responsibility for characterizing a pandemic crisis was his. In an emergency meeting with David Mathews, secretary of Health, Education, and Welfare (HEW), Sencer—supported by his boss, Dr. Theodore Cooper—made the case for universal immunization. Any decision had to be made punctually, for Washington had only a brief window of opportunity to order the vast quantity of fertile eggs required to manufacture a vaccine for the next flu season. Mathews, it turned out, had just finished reading Alfred Crosby’s new book, Epidemic and Peace: 1918, and he was thus vividly aware of the carnage wrought by the 1918 pandemic. On 15 March, the secretary sent a note to the director of the budget, warning that “the indication is that we will see a return of the 1918 flu virus.” Of course, 1976 was an election year, and the White House was stunned when it learned of Mathews’s memo. President Gerald Ford, already being pressured by Ronald Reagan’s succcess in the early Republican primaries, hardly wanted voters dropping dead of influenza on the way to polling stations in November. Accordingly, he tried to turn the swine flu threat into a political asset by dramatically announcing a crash program to vaccinate more than 100 million Americans.66

The administration, however, quickly discovered the vagaries of relying upon the marketplace to supply the emergency vaccine, as well as the difficulties inherent in fragmented local governments supervising mass immunization. Since a 1974 court decision that found drugmaker Wyeth liable for the calamitous side effects of its polio vaccine, the big pharmaceutical companies had been rushing to drop vaccines from their product lines. To induce the companies to start up fertile egg production lines, Ford had to bribe them with $135 million appropriated from Congress for the purchase of vaccines. He then had to submit to blatant extortion by the casualty insurance industry, which refused to provide coverage to the manufacturers unless the federal government agreed to indemnify any claims against the insurers. (An incredulous California congressman, Henry Waxman, asked Theodore Cooper: “Dr. Cooper, are you in effect saying that the insurance industry is using the possibility of a swine flu pandemic as an excuse to blackmail the American people into paying higher insurance rates?”) The manufacturing processes, moreover, were proprietary secrets: although the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) had to approve the final vaccines, the government could exert little direct quality control over their production. As a result, Parke-Davis produced several million doses of the wrong strain, and general industry output fell below government expectations.67

While the Ford administration was wrestling with these supply-side problems, there was eerie silence on the demand side. The Fort Dix outbreak had died away and no new swine flu cases had emerged on the East Coast or, according to the WHO, anywhere else in the world. One of the CDC’s key advisors, polio vaccine pioneer Albert Sabin, counseled Sencer that it would be best to actively stockpile the new vaccine in the public-health network but delay the actual immunization campaign, except for high-risk groups, until swine flu reemerged. Sencer felt that approach was too risky, because air travel now guaranteed that any pandemic would be “jet-spread” within hours. Immunization began in October, with very uneven zeal across the country: some localities, such as Delaware, organized impressive campaigns that resulted in 80 percent coverage, while others, like New York City (where the Times editorialized against the program), made only risible gestures resulting in less than 10 percent of the population being immunized. By election eve, with no sign of the dreaded swine flu, public misgivings about the immunization campaign were widespread; two weeks after Jimmy Carter’s defeat of Ford, the deaths of several elderly people from the rare Guillain-Barré syndrome were circumstantially linked to the vaccine, and immunization was abruptly halted.68

From that point on, swine flu became synonymous with political fiasco. Carter’s new HEW secretary, Joseph Califano, asked two Harvard scholars, Richard Neustadt and Harvey Fineberg, to undertake a case-study of the Ford administration’s response to the Fort Dix outbreak. Although Neustadt and Fineberg discovered a definite chain of error, including exaggerated estimates of swine flu’s similarity to the 1918 virus and the CDC’s failure to heed Sabin’s advice about stockpiling, they found it impossible to dismiss the CDC’s original apprehensions as irrational or irresponsible. Indeed, Califano himself later conceded that he would have probably made the same decision as Mathews, his ill-fated predecessor. As Neustadt and Fineberg document, expert opinion inside the communicable disease community leaned toward the position that overreaction had been preferable to no reaction. (Or, as Edwin Kilbourne put it, “better a vaccine without an epidemic than an epidemic without a vaccine.”)69 On Capitol Hill, however, there was little sympathy for HEW or the CDC.70

The most vicious backlash came not from opposition Democrats, but from the Reagan wing of the Republican Party. When the Carter administration tried to fund a permanent federal flu vaccination program in 1978 it ran into fierce opposition from Senator Richard Schweiker of Pennsylvania in the Senate Health Subcommittee. “It is really sort of ironic,” the senator scolded Califano. “We just came through the worst medical disaster in history in terms of modern technology, and you want to give them a prize for what has been done.” Two years later, Reagan appointed Schweiker as secretary of Health and Human Services (the cabinet successor to HEW) and the program was terminated. Under Reagan and Schweiker federal grants for successful immunization programs for common diseases such as measles were also drastically cut, and influenza vaccine development was handed back to a pharmaceutical industry that had less enthusiasm than ever for the product. The trend—endorsed by Carter and Califano—toward more widespread, even universal, annual flu immunization was stopped cold in its tracks.

Influenza, indeed, became something of a Washington pariah, “the top of no one’s list,” according to Neustadt and Fineberg.71 Careers had been wrecked by implosion of the immunization campaign, and no ambitious public-health official wanted to risk the ignominy that Congress had inflicted upon former CDC Director Sencer and his immediate superior, Dr. Cooper. Over succeeding decades, moreover, the swine flu episode has become even more of a black legend militating against proactive public-health initiatives. Even in the late 1990s, with the emergence of the most deadly strain of influenza ever seen by science, the nonepidemic of 1976 was still casting a larger shadow over federal policy-making than the infinitely more serious 1918 pandemic.