6

Rites of Passage

saṃskāra

Axel Michaels

Life-cycle rituals—or rites de passage as they have been termed since Arnold van Gennep (1909 )—are universally observed ceremonies to ritually identify changes in life. They thus mark major physical and/or psychological developmental stages. In the Indian (Hindu, Buddhist, and Jain) contexts, these rituals are called saṃskāra . When Ron Grimes says, “(i)f van Gennep had not coined this idea, we would not see births, initiations, weddings and funerals as being similar rituals, because these ritual types are not always combined by their practitioners,” 1 he is only half way right. The term saṃskāra is already such a cover term for life-cycle rituals.

Hindu tradition recognizes up to forty saṃskāras , 2 of which, by the medieval period, sixteen had achieved a nearly canonical status even though they are sometimes given different names (see Table 6.1 ). Almost all traditional Hindu families observe until today at least three saṃskāras (initiation, marriage, and death ritual). Most other rituals have lost their popularity, are combined with other rites of passage, or are drastically shortened. Although saṃskāras vary from region to region, from class (varṇa ) to class, and from caste to caste, their core elements remain the same owing to the common source, the Veda, and a common priestly tradition preserved by the Brahmin priests.

Table 6.1. Hindu life-cycle rites

| Phases of Life | Ritual |

|---|---|

| Prenatal rituals | 1. Procreation, insemination (garbhādāna, niṣeka ) |

| 2. Transformation of the fruit of love to a male fetus (puṃsavana ) | |

| 3. Parting of the hair of the pregnant woman (sīmantonnayana ) | |

| Birth and childhood | 4. Birth ritual (jātakarma ) |

| 5. Name giving (nāmakaraṇa ) | |

| 6. First outing (niṣkramaṇa ) | |

| 7. First solid food (annaprāśana ) | |

| Adolescence | 8. Tonsure or first cutting of the hair (cūḍākaraṇa, caula ) |

| 9. Ear piercing (karṇavedha ) | |

| 10. Beginning of learning (vidyārambha ) | |

| 11. Initiation or Sacred Thread ceremony (upanayana, vratabandhana ) | |

| 12. Beginning of learning (vedārambha ) | |

| 13. The first shave (keśānta ) | |

| 14. The end of study and returning to the house (samāvartana ) | |

| Marriage | 15. Wedding (vivāha, pāṇigrahaṇa ) |

| Death and Afterlife | 16. Death ritual (antyeṣṭi ) |

| Joining the ancestors (sapiṇḍīkaraṇa ) | |

| Ancestor worship (śrāddha ) |

The Term SaṂskāra

Saṃskāra is usually translated as “rite of passage” or “sacrament,” but these concepts encompass only a part of its meaning. As Śabara, a fifth-century scholar, says, the decisive thing is that the saṃskāras are applied to make someone or something fit or suitable for some purpose (yogya ), for wholeness or “salvation,” for example, as a sacrificial offering. 3 The gods accept only what is suitable to them, that is, properly composed or put together, and therefore perfect. Similar to “Sanskrit,” literally, “the totally and (correctly) formed [speech]”), saṃskāra, therefore, means the perfection of ritual acts. So, in Vedic ritual context the term saṃskṛta is often used for purification actions.

The special suitability (yogyatā ) of saṃskāras is generally understood in a double sense, at least: first, as the elimination of the unclean, the faulty, and tainted, and second as creating the eligibility to carry out sacrificial rituals. Impurity and faults are created through natural birth. Thus, in Manu’s Law Code (MDh 2.26–28), it is said that the fire sacrifices (homa ) carried out during pregnancy, the ritual of birth, the tonsure, and the girdling eliminate the unclean substance (enas ) of the twice-born, which is created by semen and the uterus:

The perfection (saṃskāra ) of the body, should be performed for twice-born men with auspicious Vedic ritual actions beginning with the rite of impregnation that purifies a man both in the hereafter and here (in this world). The fire offerings for the foetus, the birth rites, the first haircut and the tying of the Muñja-grass belt, wipe away from the twice-born men the guilt of the seed and the guilt of the womb. By the study of the Veda, vows, offerings into the fire, study of the triple Veda, sacrifices, sons, the (five) great sacrifices and the (other) sacrifices, the body is made fit for the Veda (or the brahman , ultimate reality).

The commentator Medhātithi emphasizes that semen and uterus are the causes of uncleanness. Harīta, another legal scholar quoted in the Saṃskāratattva , makes it even clearer, saying that the man places the fetus in the womb of his wife by means of the ritually carried out procreation (garbhādāna ). 4 The womb thus becomes suitable for the reception of Veda. With the puṃsavana ritual, he then transmutes the embryo into a male fetus. With the ritual of parting the hair of the pregnant woman (sīmantonnayana ), he eliminates the impurity imparted by the parents, and the uncleanness of semen, blood, and uterus are eliminated by the rituals of birth (jātakarma ), naming (nāmakaraṇa ), presenting the first solid food (annaprāśana ), tonsure (cūḍākaraṇa ), and the bath that concludes the period of study (samāvartana ).

Sources

The sources for the saṃskāras are mostly texts on domestic rites (Gṛhyasūtras), legal texts (Dharmaśāstras and smṛtis ), medieval compendia (Nibandhas), and numerous ritual handbooks (paddhati, vidhi ). 5 The authors of these texts often refer to local customs and variations. The Dharmaśāstras do not normally give detailed descriptions of the performance of the rituals; only the Gṛhyasūtras and the ritual handbooks do so. Neither do Vedic Saṃhitās and Brāhmaṇas contain detailed rules for the saṃskāras, but verses and passages from these texts have been used as mantras in the saṃskāra rituals.

It is in the Gṛhyasūtras that we find detailed descriptions of the main bodily (śarīra ) saṃskāras . 6 Generally, they begin—as in the Pāraskaragṛhyasūtra (PārG )—with marriage (vivāha ), followed by the pregnancy rites (garbhādāna, puṃsavana ), the ritual parting of the hair (sīmantonnayana ), the name-giving ceremony (nāmakaraṇa ), the first feeding of solid food (annaprāśana ), the first haircut (cūḍā-karaṇa , -karma ), the initiation (upanayana ), and other educational rites such as the taking leave of one’s teacher (samāvartana ). 7 The death and ancestor rituals (antyeṣṭi, śrāddha ) are mostly dealt with in a different place—in the PārG , for instance, at the end of the text.

The Dharmaśāstras generally list the saṃskāras in their sections on right conduct (ācāra ) with a focus on marriage and initiation but do not give many details of the ritual procedure of the saṃskāras . Some Smṛtis like that of Nārada even mention these rites only indirectly. However, the Smṛtis presuppose the saṃskāras inasmuch they mark the transition from the Vedic world to the class and caste society of Hinduism, that is, the establishing of Smārta Hinduism.

The Nibandhas mostly follow the traditional list of the sixteen saṃskāras . Thus, the Saṃskāra section of the Sṃrticandrikā of Devanabhaṭṭa (composed between 1200 and 1225), begins with the rite of impregnation (garbhādhāna ) and ends with marriage (vivāha ). The Dharmasindhu by Kāśinātha Upādhyāya (1790/91) follows the same order and deals with numerous qualifications and exceptions. The Nibandhas also include many variations mixed with other rites and astrological considerations.

History of SaṂskāras

Saṃskāras have been shaped in the middle Vedic period, starting around 500 bce , when the higher classes of the Āryans began to settle in the Gangetic plains. In the early Vedic phase, the initiation was a consecration (dīkṣā ) into secret priestly knowledge and an initiation, a kind of “proto-upanayana, ” into certain sacrifices. It was also a privilege for those who wanted to learn the Veda or to perform a sacrifice, a privilege mostly restricted to the twice-born men. The dīkṣā was then more a ritual preparation for the institutor of the sacrifice than a life-cycle ritual. The initiation (upanayana ) of the middle Vedic phase, on the other hand, demarcated the social and ritual boundaries between different social groups and the separation of the higher classes (varṇa ) from the rest of the society (cf. Tab. 6.3). 8

Various factors may have been responsible for this development, especially acculturation problems vis-à-vis the indigenous population owing to the transition of the Āryans from a semi-nomadic to a settled life. In the transculturation processes, such as mingling with the resident population and their doctrines and religions, the admission to the Vedic rituals, mainly the fire sacrifice, and the marriage rules had to be regulated. By this, the Āryans demarcated themselves from the indigenous population. From the beginning of the Common Era, the sacred thread became their symbol of this boundary. The non-initiated were outsiders, marginal groups, or even enemies (e.g., the vrātyas ). Only by celebrating upanayana , that is, the ritual birth of the boys into the Veda, did one become a twice-born; those who could not be initiated—young children and, to a certain extent, women—remained in the impure state of a Śūdra. The non-initiated were not allowed to take part in the Brahmanical rituals; they could not maintain the Vedic domestic fire, intermarry with the twice-born classes, or partake in joint meals. Thus they remained “out-casts.”

This linkage of life-cycle rituals with social status was the basis of the Hindu caste society creating a deep connection between descent and matrimony. Initiation now meant acceptance into patriarchal society and instruction in the study of the Veda—the literal meaning of upanayana is “leading (to the teacher)” or more precisely “leading” (of the student by the teacher to his self)—along with the initiation into the sacrificial practices derived from that. All this also resulted in his ability to marry. Through initiation, the youth becomes a member of a caste, an apprentice, entitled to perform sacrifices, and a candidate for marriage all at once.

The Traditional Hindu Rites of Passage

Among the sixteen bodily (śarīra ) saṃskāras that are still performed are the name-giving ceremony (nāmakaraṇa ), the first rice feeding (annapraśanna ), tonsure (cūḍākaraṇa ), initiation (upanayana ), marriage (vivāha ), and the funeral (antyeṣṭi ). There are many additional life-cycle rituals, with a great number of local variations, still performed in South Asia. Thus, a small Newar Buddhist compendium from the eighteenth century (Bajrācāryya and Bajrācāryyā 1962) lists the following saṃskāras (Table 6.2 ).

Table 6.2. Newar Buddhist life-cycle rituals

| 1. (Introduction on embryology) 9 |

| 2. Cutting the umbilical cord (nābhikṣedana [sic ]) |

| 3. Birth purification (jātakarma ) |

| 4. Name giving (nāmakarma ) |

| 5. Showing the sun [niṣkramaṇa ] |

| 6. First feeding of fruits and cooked rice (phalaprāśana, annaprāśana ) |

| 7. Protection against the grahas with a necklace (graharakṣā ) |

| 8. Opening the throat (kaṇṭhaśodhana ) |

| 9. First head shaving [cūḍākarma ] |

| 10. Initiation (bartabandhaṇa [sic], vratabandhana ) |

| 11. First monastic initiation (pravaryyāgrahaṇa ) |

| 12. Consecration of a Vajrācārya priest (vajrācāryyābhiṣeka ) |

| 13. Marriage of the girl to the bel fruit ([= Nev. ihi ], pāṇigraha ) |

| 14. Marriage (kanyādāna ) |

| 15. Eating dishes together from the same ritual plate (Nev. nikṣāḥbhū ) |

| 16. Dressing the hair (keśabandhana ) |

| 17. Girl’s seclusion (Nev. nārī jāti yāta yāyāgu kriyā raja śolā bidhi, bādhā taye [= bārhā tayegu ]) |

| 18. Worship of the aged 1 (Nev. bhimaratha kriyā, bṛ [hat ] nara bṛ [hat ] nārī ,1 (Nevārī) jaṃko ) |

| 19. Worship of the aged 2 (debaratha [sic, devartaha ], 2 jaṃko ) |

| 20. Worship of the aged 3 (mahāratha , 3 jaṃko ) |

| 21. Ripening of the karma (karmavipāka ) |

| 22. First death rites (utkrānti ) |

| 23. Death rites (mṛtyukriyā ) |

| 24. Removal of impure things from the deceased (Nev. chvāse vāyegu ) |

| 25. Fumigation (Nev. pākhākūṁ tha-negu ) |

| 26. Removal from the house and making the litter (Nev. duḥkhā pikhāṁ tiya, sau, sāyegu ) |

| 27. Death procession (Nev. siṭhaṃ yaṃkegu ) |

| 28. Rituals at the cremation ghāṭ (Nev. dīpe yāyāgu kriyā ) |

| 29. Disposal of the ashes (aṣṭi parikṣāraṇa ) |

| 30. Drawing a maṇḍala to prevent a bad rebirth (durgati pariśodhana maṇḍala kriyā ) |

| 31. Feeding of the deceased (Nev. nhenumā ) |

| 32. Setting out cooked rice etc. for the departed spirit (Nev. pākhājā khāye ) |

| 33. Removal of death pollution (Nev. duveṃke ) |

| 34. House purification (gṛha sūddha gvāsagaṃ kriyā ) |

| 35. Offering of balls (piṇḍa ) for ten days (daśapiṇḍakriyā ) |

| 36. Offering of piṇḍas on the eleventh day after death (ekādaśa piṇḍa kriyā ) |

| 37. Further piṇḍa rituals (Nev. piṇḍa thayegu kriyā ) |

| 38. Offering of piṇḍas to three generations (Nev. lina piṇḍa ) |

| 39. Protection of the guru (gururakṣaṇa ) |

| 40. Ancestor ritual (śrāddha ) |

| 41. Removal of the piṇḍas (Nev. piṇḍa cuyegu sthāna ) |

The list of Table 6.2 is interesting for many reasons. It contains a mixture of all kind of Hindu and Buddhist life-cycle rituals, including the death and ancestor rituals. Rituals for the male are combined with rituals for girls, women, and the aged. Sometimes subrituals are listed separately. It is also an example of the local variations that saṃskāras can demonstrate. The structure is, however, similar to other lists of saṃskāras , which—following the age groups—can be classified into prenatal, birth and early childhood, initiation (educational), marriage, old-age, death, and ancestor saṃskāras .

Prenatal Saṃskāras

The prenatal life-cycle rituals are mainly concerned with the promotion of the fertility of the woman and health of the fetus and mother. The authors of Dharmaśāstras discussed whether the rites are more concerned with the fetus and male semen (garbha ) or the mother and the womb (kṣetra ). In the latter case, the rite should be performed only once. Since conception is regarded as a ritual and spiritual act, the ritual through which the man places his semen in the womb, that is, the insemination (garbhādāna, niṣeka ), should be performed on the fourth (caturthī ) day after the beginning of the menstruation, together with prayers and purifications. 10 It is doubtful that this ritual was often practiced.

The transformation of the fruit of love to a male fetus (puṃsavana ), which occurs in almost all manuals, is to be performed in the third or fourth month of pregnancy. In ancient India, some people believed that the gender of a child is already fixed at the time of insemination, while others opined that the embryo remains in an undifferentiated status for three months and assumes its sexual identity only after three months. The puṃsavana is performed by feeding certain food items or juices to the wife after she has fasted, taken a bath, and put on new garments.

The parting of the hair of the pregnant woman (sīmantonnayana ) is performed between the fourth and eighth month of pregnancy in order to protect mother and fetus from evil influences. The main act consists of the husband parting the hair of his wife with darbha grass or a porcupine quill and placing vermilion in the parting of her hair.

To the prenatal rites belongs also the South-Indian viṣṇubali ritual performed in Vaikhānasa families along with sīmantonnayana . It consists of an offering (bali ) to Viṣṇu and a sweet rice pudding (pāyasa ) given to the pregnant woman in order to make the child a devotee of this god (Huesken 2008). It is believed that Viṣṇu himself will then initiate the newborn child so that it does not need any other sacrament or initiatory rite to make it a Viṣṇu-devotee and to make it eligible to become a Vaikhānasa priest.

Birth and Childhood Saṃskāras

The majority of the life-cycle rituals focus on childhood and adolescence, the most perilous time of life in premodern societies. The birth ritual (jātakarma ) consists of cutting the umbilical cord, feeding honey (medhājanana ), and blessing the new child (āyuśya ) and the mother (mātrābhimantraṇa ), or touching the shoulders of the child (aṃsābhimarśana ). Other acts, such as the first breastfeeding, might also become ritualized by chanting a mantra . Some texts prescribed that the father or five Brahmins blow over the child.

The name-giving ceremony (nāmakaraṇa ) is only performed after the eleventh day, but it is often celebrated together with the next two or three saṃskāras . It concerns the astrologically determined name whispered by the house priest into the left ear of the child. The name is mostly kept secret and only used for ritual purposes. The first outing (niṣkramaṇa ) is a ritual where on an auspicious day within the first three months the child is taken out of the house and shown to the sun (ādityadarśana ). This ritual demarcates the end of the impure period. After six months, the child is given the first solid food (annaprāśana ), most often a sweet rice preparation.

The tonsure or first cutting of the hair (cūḍākaraṇa, caula ) is an ancient ritual that takes place between the first and third year of the child. The ideal time is when the fontanel in the skull of the child is closed, but today the ritual is mostly combined with the initiation (upanayana ). The priest with the help of the father or maternal uncle cuts small locks of hair from four sides of the child’s head. The barber then shaves the rest of the hair except for a little tuft (śikhā ) that is regarded as the seat of the paternal lineage. The ear-piercing ritual (karṇavedha ), during which the priest or father pierces both earlobes with a gold, silver, or iron needle—depending on the class (varṇa ) of the family—is to be performed on an auspicious day in the seventh or eighth month.

Initiatory Saṃskāras

Most childhood rituals are performed for both male and female children. The initiatory rituals, however, are only for boys. The marriage is regarded as the initiation of the girls. The saṃskāras of adolescence are often presented as educational rituals. In fact, they focus on introducing the boy into the adult world and preparing him to take on his social and ritual responsibility. They usually begin with the cutting of the hair (cūḍākaraṇa given above), followed by the ritual beginning of learning (vidyārambha ) through which the boy is authorized to learn the Veda.

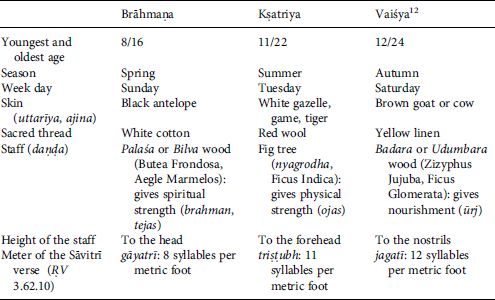

This initiation or sacred thread ceremony (upanayana ) is the first of the more complex rituals (see Table 6.3 ). 11 The age of initiation varies according to status and class. The time of initiation is determined astrologically. The actual preliminary rituals begin with the tonsure (cūḍākaraṇa ), when the hair of his head is shaved, except for a small strand (the śikhā ). After this, the actual initiation (upanayana ) takes place. It is considered a second birth, and is divided into the dedication as an ascetic, as a pupil, and as a man. The primary act in the dedication as an ascetic is the laying-on of the holy cord. During this dedication, the son, if he is a Kṣatriya, is given, among other things, an antelope skin and a stick, the few possessions of an ascetic. In the subsequent dedication as a pupil, the priest teaches the son, both covered by a blanket, the Gāyatrī hymn (ṚV 3.62.10), which is considered to be a condensed form of the entire Veda. In return, the son honors the priest as his teacher and, according to ancient tradition, brings him firewood to keep up his fire. He goes on a begging tour round the invited guests, too. After this, once more, there is the symbolic and ritual celebration of the study of the holy texts. The son again goes on a round of begging, lights a special fire, and takes a special bath, which makes him into a pupil of Vedic (snātaka ), although in the classical ritual, the ritual bath is taken at the end of the period of studentship. In a more playful episode called (deśāntara ), the pupil sets off to Benares for twelve years of studies, a short time after which, his uncle on his mother’s side and the priest hold him back at the garden gate, promising to find him a beautiful woman to marry. The end of these “studies,” too, is arranged as a ritual. First, the samāvartana fire is lit and honored, and then the son receives yogurt and other foods from the priest, as well as a white loincloth and the holy cord. Finally, the initiate dresses in new, worldly (nowadays generally Western) clothing and looks at himself in the mirror. With the upanayana the boy is considered a dvija or twice-born, that is, he is ritually born into and through the Veda and has completed his second birth after the physical birth from the mother, which is the first birth. Traditionally the boy is to stay in the house of the priest or teacher (guru ) for many (ideally twelve) years until he has mastered the Veda. But this nowadays happens only in very traditional Brahmanical families. With the samāvartana ritual and his returning from the first traditional life-stage (āśrama ), the liminal phase of celibacy and learning (brahmacarya ), the boy enters into the second life-stage as a married householder (gṛhastha ).

Marriage Saṃskāras

For the Gṛhyasūtras, a man becomes only complete and fit to sacrifice when he has married. Most Hindu weddings (vivāha, pāṇigrahaṇa ) last for days and contain a great number of subsidiary rites. The core elements involve the selection (guṇaparīkṣā ) of the bridegroom by the parents of the bride, engagement (vāgdāna ), the marriage procession (vadhūgṛhagamana ), the reception of the bridegroom’s procession, the bestowal of the bride by her father to the groom (kanyādāna ), taking the bride’s hand (pāṇigrahaṇa ), exchange of garlands between the bride and groom, the lighting and circumambulation of the sacred fire (agnipradakṣiṇā, parikramaṇa, pariṇayana ), seven steps (saptapadī ), and a meal eaten together. Often a sacred necklace (maṅgalasūtra ) is given to the bride by the groom, who also may apply vermilion (sindhūra ) on the bride at the parting of her hair.

Old-Age, Death, and Ancestor Rituals

In the “canon” of the sixteen traditional Hindu rites of passage, only the death ritual (antyeṣṭi ) is mentioned. Other rituals, however, have to be included in this category. This holds true, for instance, for rituals that concern the third and fourth life-stage (āśrama ), the ascetic withdrawal from the family home and forest dwelling (vānaprastha ) and the complete renunciation without domestic fire and wandering (saṃnyāsa ). In some areas, there are non-ascetic old-age rituals, such as the worship of the aged: for instance, when, among the Newars of Nepal, someone becoming seventy-seven years, seven months, and seven days old (eighty-eight years, eight months, eight days, etc.) is worshiped in a large clay vessel and then carried on a little chariot through the vicinity of his or her house (bhīmaratharohaṇa ). 13

In the death ritual (antyeṣṭi ), specialized “impure” priests perform the final saṃskāra , which is meant to prepare the deceased for his or her journey through the underworld to heaven. The corpses of Hindus are cremated—with the exception of small children, ascetics, and persons inflicted by certain diseases. Upon the death of an individual, the body is wrapped and brought to the place of cremation, where the eldest son or some other male relative lights the pyre, together with the priest. The fire is meant to bring the deceased to the ancestors. This is sometimes regarded as the third birth. The ashes are generally thrown into a river.

After the death ritual, close relatives are regarded as impure for a certain period, generally eleven to thirteen days. During this period, they are not allowed to enter a temple or consume salt. The deceased (preta ) are then in a weak ghostly state. They are always hungry and without a place to live, until the chief mourner has made a body out of wheat-flower or rice balls (piṇḍa ). On the twelfth day, or after one year, the deceased is united with his ancestors in a ritual called sapiṇḍīkaraṇa . In this ritual, a piṇḍa representing the deceased is mixed with three other piṇḍas representing the father, grandfather, and great-grandfather. Afterwards the deceased will be worshiped in common and obligatory śrāddha rituals as an ancestor by his relatives.

SaṂskāras as Rituals of Transcendence

For the Gṛyasūtras and Dharmaśāstras a saṃskāra is a ritual identification with the eternal and ineffaceable, the Absolute. Thus, the initiation of the son is equated with, among others, the father, the Veda, the sacrifice, and the fire because it is only in this way that he can participate in the wholeness and immortality. If this substitution is perfect (saṃskṛta ), the rite has an effect ex opere operato , of and in itself, without any belief in it, by virtue of the ritual equivalence. The second birth proceeds from the womb of the Veda and the sacrifice, with which the Brahmanical teacher and the boy are identified, and not from the womb of the mother. This regulation is based on ritual chains of identification, important in Brahmanical Hinduism, such as the following: Veda/gods (= immortality) = sacrifice = man (mortality), or, as the Brāhmaṇa of the Hundred Ways, the Śatapathabrāhmaṇa , says, “Man is the sacrifice” (ŚB 1.3.2.1). In middle Vedic texts, sentences like the following occur repeatedly: “The person who does not sacrifice is not even born yet” (ŚB 12.2.1.1). By equating the immortal sacrifice with mortal man, immortality itself can only be saved by man becoming (at least thought of as becoming) immortal; this occurs by means of a substitution of the father by the son.

Certainly, this saṃskāra theory of the ancient Indian legal scholars brings in a new viewpoint—that of transcendence—in the discussion of rites of passage, which, ever since van Gennep, has been loaded down too much with functional and structural aspects. Van Gennep and Victor Turner (the latter less so than the former) saw the rites of passage in the life cycle for the most part as a means of cementing and renewing social relations, as social mortar, so to speak. And indeed, even though saṃskāras mostly focus on individuals, 14 they should not primarily be regarded as events in the life of individuals but as events that constitute and reaffirm socioreligious relations and groups.

But in rituals of the life cycle, the fear of man confronted with his finite existence is also expressed. For evidently every change, whether of a social or biological kind, represents a danger for the cohesion of the vulnerable community of the individual and society. Irruption and dissolution threaten, particularly with drastic events, especially in extensions and shrinkages of the social group, namely the family: births, in which a new human being is accepted; marriages, in which a family member is integrated into a new assemblage and leaves another; or death, when a member leaves forever. These are also radical interventions in the social group as an economic unit. With marriage, a source of labor leaves one family and enters another—in Hinduism, the bride, as a rule, is regarded as a gift (kanyādāna ), which does not create a reciprocal obligation in the bridegroom; in initiation, a boy is fully integrated into the economic cycle; death removes a person from this cycle.

In that man equates himself with the unchangeable in certain rites of passage, he appears to counteract the uncertainty of the future, of life and death. Usually it is a matter of relegating the effects of nature or of mortality: birth, teething, sexual maturity, reproduction, and dying. In many life-cycle rites of passage, the natural is recreated again, so that nature becomes sacral culture. “Man is born (by means of initiation) into a world he (ritually) creates himself,” says the Śatapathabrāhmaṇa (6.2.2.7).

Thus, a classificatory case is made of the individual, and rituals help to classify. A legitimate and socially accepted father is made of a procreator; a legitimate mother of a child bearer; a legitimate wife is made of a woman; and a full member of the social group is made of a boy or girl. In ancient Rome, the pater familias had to lift the child up before it was recognized as legitimate. One who is dead is made an accepted ancestor; in the Hindu death ritual, he receives a new body from the mourners, and thus the strength to “survive,” or, more appropriately, to attain heaven.

If these ritual substitutions and equivalences were not made, disorder would dominate. A bisexual union without a marriage ritual is mere cohabitation; a dead soul not ritually cared for is an unpacified soul, which can quickly become a threatening ghost; a non-initiated member is the same as a child without rights. A non-initiated Brahmin, say the Indian legal texts, is a Brahmin by birth only. He is a once-born, the same as one who may not hear nor teach the Veda; he is as one who is ill or cast out. Rites of passage in the life cycle establish and repeat this identification with the immortal by constant repetition of the perpetually unchanging, or by referring to it. They create, preserve, and strengthen identity, and in this manner, they strengthen the individual and the social group. 15