23

Titles of Law

vyavahārapada

Mark McClish

The term vyavahārapada has two related meanings: “a matter under dispute” and “an area of litigation,” sometimes rendered as a “title of law.” 1 Both refer to the subject of a legal dispute, with the former emphasizing the matter at stake in a particular lawsuit and the latter a theoretical category of transactions from which plaints typically arise. The second of the two meanings predominates in the dharma tradition, where the vyavahārapadas represent the categories of private transactions that can be litigated in royal courts. Although such bodies of rules have probably existed in some form since at least the time of Aśoka (third c. bce ) and Khāravela (ca . second–first c. bce ), they were first codified in the Arthaśāstra of Kauṭilya . It is only in the Mānava Dharmaśāstra , however, that they are presented taxonomically and first called vyavahārapada s. Manu (8.4–8.7) lists eighteen:

The vyavahārapada s are distinct from other kinds of law in a few different ways, which will be useful to keep in mind as we explore their history in the dharma literature. First, they pertain specifically to cases in which a private party feels it has suffered an injury at the hands of another and goes voluntarily to the king or royal court to make an accusation. This is made clear in the Yājñavalkya Dharmaśāstra , which presents the earliest definition of vyavahārapada :

smṛtyācāravyapetena mārgeṇādharṣitaḥ paraiḥ |

āvedayati ced rājñe vyavahārapadaṃ hi tat || (YDh 2.5)

If someone, injured by others in a manner opposed by smṛti or proper conduct, announces it to the king, that is a vyavahārapada .

In this sense, the vyavahārapadas are, in principle, distinct from the rules that the king may enforce on his own initiative for the purpose of public order (these latter are categorized under such headings as prakīrṇaka , “miscellaneous rules,” or kaṇṭakaśodhana , “clearing thorns”).

Second, the body of rules that comprise the vyavahārapadas is presented in abstraction from any specific social group, whose own particular rules are usually referred to as “customary law” (caritra ; ācāra ) or as various types of contextual and limited dharmas : e.g., regional (deśadharma ), caste (jātidharma ), or family (kuladharma ). Such rules are in force only among their respective groups, and the authority assigned to them relative to the rules of the vyavahārapadas varies, as explored below.

Finally, and following from both of these, the vyavahārapadas are related specifically to the adjudication of disputes in royal courts. Although they were not the only rules bearing on the resolution of disputes in royal venues and were not to be applied like modern statutes (BṛSm 1.1.114), they nevertheless provided the fundamental jurisprudential framework through which royal judges reached their verdicts.

Within Dharmaśāstra, the vyavahārapada s are one part of the more general topic of “litigation” (vyavahāra ). Its other component is “judicial procedure” (vyavahāramātṛkā ). Of these two, the substantive law of the vyavahārapada s receives far more attention than the procedural rules of vyavahāramātṛkā . Although all dharma texts, from the beginning of the tradition, possess some discussion of the legal domain represented by vyavahāra , it only becomes a major topic beginning with the Mānava Dharmaśāstra , of which around a quarter is devoted to the topic. A few centuries later, Yājñavalkya presents vyavahāra as one the three major topics of Dharmaśāstra, alongside ācāra (“conduct”) and prāyaścitta (“penance”), and he spends a third of his text discussing it. After this, vyavahāra continues to grow in importance in the smṛtis of Nārada, Bṛhaspati, and Kātyāyana, who show either an exclusive or an overwhelming interest in it. It is in these three texts, in particular, that many of the finer points of vyavahāra are examined. Quite the opposite of this, however, are texts such as the Vaiṣṇava Dharmaśāstra and Parāśara Smṛti . The former treats the topic more briefly than Manu, and the latter, at least in its extant form, does not deal with vyavahāra at all.

The Origins of the Vyavahārapadas and the Nīti Tradition

The roots of the vyavahārapada s lie outside of the dharma tradition. In order to trace their earliest history, we must look more closely at the development of the concept of vyavahāra itself. The earliest attested uses of vyavahāra and related forms in Indic texts refer not to law at all but to “transaction,” “exchange,” or “use.” This can denote a variety of interactions and activities, often with an emphasis on their transactional nature, but also comes to refer specifically to “trade” as mercantile activity (e.g., ĀpDh 2.16.17). In the ritual manuals, someone with whom interaction is allowed is called vyaāvahārya “to be interacted with” (e.g., KātŚr 22.4.28), in this sense, denoting full access to social interaction and membership in society (cf . YDh 3.222; NSm 14.10). Forms of the term are used more abstractly in the early grammatical literature, where vyavahāra can refer to the characteristic linguistic practices of specific communities (e.g., Patañjali, Mahābhāṣya I 284.2–284.8, I 379.17–380.5) or more generally to the common language observed in everyday interaction, as opposed to the highly refined language of the Vedic Saṃhitās (e.g., Nirukta 13.9).

These meanings persist in the dharma literature and continue to flesh out the greater semantic range of the term. Moreover, they give us a sense of how the specifically legal valence of vyavahāra might have developed. If vyavahāra represents observable, norm-governed interactions, and if these interactions delineate communities to which some are admitted and others not, then we are already very close to the notion of vyavahāra as a legal domain.

The earliest explicitly legal use of the term comes not in the dharma literature, but in the edicts of the Emperor Aśoka. In his fourth pillar edict (ca . 242 bce ), the emperor expresses his desire for viyohālasamatā , “uniformity in vyavahāra ,” and daṃḍasamatā , “uniformity in punishment,” on the part of his regional officials called Lajūka s. What Aśoka means precisely by vyavahāra here is not clear from the context, but its use as a technical legal term is. Some, such as Hultzsch (1925 : 125), have interpreted it as “judicial proceedings,” in keeping with its later use and forming a tidy dyad with daṇḍa as “procedure” and “punishment.” But, the meaning here need not be so narrow. Elsewhere (Separate Rock Edict I, Jaugaḍa and Dhauli), Aśoka refers to officials called nagalaviyohālaka s (Skt. nagaravyaāvahārika s), who are ascribed clear judicial functions. These officers appear to be the same as the mahāmātā (“high official”) called nagalaka (“city manager”) mentioned in the Jaugaḍa edict. Nomenclature of this type is also used for legal officials in Buddhist texts of the same general era: the vohārikamahāmatta is mentioned in the Mahāvagga (1.40.3) and Cullavagga (6.4.9). 2 If these represent “city judges,” as seems to be the case, then vyavahāra probably has the broader meaning of “law” or “state law,” in the sense of “litigation in state courts.” In another early inscription, King Khāravela (ca . second–first c. bce ), relates that, among other subjects, he has studied vavahāravidhi (or, perhaps, vavahāra and vidhi ). This compound (vyavahāravidhi ) is found in both Manu (8.45) and Yājñavalkya (2.31), where it probably means something like “legal proceedings” or “litigation.” There is no other term in the early inscriptions that more closely approximates “law” in its juridical sense than vyavahāra , and it appears that, at least by the time of Khāravela, it existed as the subject of an expert tradition.

This expert tradition on vyavahāra comes fully to light first in the Arthaśāstra of Kauṭilya , the most significant text to survive from the classical nīti tradition of statecraft. The Arthaśāstra gives abundant evidence of a comparatively well-developed expert tradition of litigation in royal courts, presenting the first full codification of the vyavahārapadas (3.2–3.20), although not by that name, as well as rules on legal procedure (3.1) and topics such as the investigation of judicial corruption (4.9). Even if we reject a Mauryan provenance for the text, we are yet justified in drawing some degree of connection between its instructions and the legal world of Aśoka and Khāravela. The term vyavahāra and related forms are common in the Arthaśāstra , where it refers sometimes to “transactions” in the abstract, and specifically to transactions that can be litigated in a royal court (Rocher 1978 ) or to an individual who has “obtained vyavahāra ” (prāptavyavahāra ), the legal status conferring the right to engage in legally binding transactions. Most importantly, though, vyavahāra refers a few times in the Arthaśāstra to the types of rules themselves to be used in legal disputes over such transactions (Olivelle and McClish 2015 ). 3 These rules are given in the third book, called Dharmasthīya , “On Justices,” under seventeen headings:

Although there is some question as to whether it was augmented over time, the Arthaśāstra ’s presentation is relatively systematic. It starts with the family, dealing first with (i) marriage law and (ii) inheritance. Then the code moves to (iii) property and (iv) nonfulfillment of conventions, both largely within the context of village life. Then we have more purely economic topics: (v) loans, (vi) deposits, (vii) labor, (viii) partnerships, (ix, xi) sales, (x) gifts, and (xii) ownership. Following are discussions of (xiii–xv) violent offenses and two appendectical topics: (vxi) gambling and (xvii) miscellaneous rules.

The Arthaśāstra also provides us our first clear sense of how vyavahāra fits into the complex legal order of the period. When the king or an appointed judge was attempting to reach a verdict in a case, there could be a variety of norms, rules, or laws bearing on a just verdict. It appears from the Arthaśāstra that these bodies of law were understood as comprising a hierarchy of four domains called the “four feet” (catuṣpada ) of law (Olivelle and McClish 2015 ). They are, in ascending order of legal authority, dharma (“righteousness”), vyavahāra (“state law”), caritra (“custom”), and śāsana (“royal edict”). The most powerful type of rule was a royal edict. If the king had issued a decree pertinent to a case, no other rule could supersede it. Failing that, the judge should look to whatever customary law (caritra ) the parties might observe, presumably because they belonged to the same private community (cf . KātSm 47). In absence of both royal decree and custom, the vyavahārapada s would have legal authority. Finally, if no pertinent rule could be found among any of these bodies of law, then dharma in a generic sense provided the normative framework for the judge’s decision. Hence, the vyavahārapada s were applied in disputes that could not be resolved with respect to decree or customary law, probably for the most part in disputes between members of different corporate groups (cf . Davis 2005 ).

The Vyavahārapadas in the Dharmasūtras

Vyavahāra and the vyavahārapada s enter the Dharmasūtras as part of the more general appropriation of the nīti statecraft tradition under the rubric of rājadharmas , “the laws for kings” (see the rājadharma chapter). The earliest Dharmasūtra, that of Āpastamba, was probably composed sometime around the reign of Aśoka, but before the Arthaśāstra , perhaps during the third century bce (Olivelle 2010b ). It is far more primitive than the Arthaśāstra in respect of legal thought, innocent of any legal sense of the term vyavahāra and possessing only a brief treatment of dispute resolution in royal courts. Āpastamba’s substantive rules cover the following areas: 4

It has often been assumed that Āpastamba represents the nascency of such legal reflection, but this conclusion is undermined by the likely existence of a contemporaneous independent tradition of vyavahāra . In this light, it seems that Āpastamba is simply operating at the margins of a more robust nīti tradition. Particularly telling, in this regard, is Āpastamba’s treatment of crime and punishment (2.27.14–2.27.21), which offers only an incomplete jurisprudence of crimes by various groups. His treatment is not an embryonic version of what will be more fully developed in the Arthaśāstra , but in fact, merely a selective emphasizing of certain legal principles, such as the degradation of Śūdras and the immunities of Brāhmaṇas.

The integration of vyavahāra into the dharma tradition, however, did change the legal authority of the former. This is explained by another section of the text, where Āpastamba enunciates the principle that the customary law of individual groups is invalid if it is opposed by scripture. Specifically, he argues that the śāstras forbid the eldest son from inheriting the entire family estate (2.14.6ff.). A few sūtras later, he expands this to a general principle: “This explains the laws of regions (deśadharma ) and families (kuladharma )” (etena deśakuladharmā vyākhyātāḥ ; 2.15.1). To the extent that vyavahāra becomes Dharmaśāstra, its primacy relative to customary law is enhanced.

The Gautama Dharmasūtra , composed not long after Āpastamba, clearly drew from the nīti tradition, and probably from the Arthaśāstra itself (see the rājadharma chapter). It is, therefore, not at all surprising that Gautama is the earliest extant dharma writer to use vyavahāra in a legal sense. His begins his discussion of state law with two sections, the first on vyavahāra (11.19–11.26) and the second on daṇḍa (11.27–11.32), recalling Aśoka’s reference to viyohālasamatā and daṃḍasamatā . What is more, Gautama’s discussion of vyavahāra prioritizes not procedure, but substantive law:

tasya vyavahāro vedo dharmaśāstrāṇy aṅgāny upavedāḥ purāṇam || (GDh 11.19)

deśajātikuladharmāś cāmnāyair aviruddhāḥ pramāṇam || (GDh 11.20)

karṣakavaṇikpaśupālakusīdikāravaḥ sve sve varge || (GDh 11.21)

tebhyo yathādhikāram arthān pratyavahṛtya dharmavyavasthā || (GDh 11.22)

His vyavahāra shall be the Veda, the Dharmaśāstras, the Supplements (aṅgas ), the minor Vedas, and Purāṇa. The Laws of regions, castes and families are authoritative when they are not opposed by the scriptures. And farmers, merchants, herdsmen, lenders, and artisans each have authority over their own group. He should consider the cases and render a rule of dharma unto them according to the relevant authority. (GDh 11.19–11.22)

Here, Gautama equates vyavahāra with Brahmanical scripture. This would appear to advocate the supplanting of vyavahāra as presented in the Arthaśāstra , a process that will be fully realized with Manu’s wholesale integration of vyavahāra into his Dharmaśāstra. Moreover, he states as a juridical principle that vyavahāra based in scripture is indeed of greater legal authority than customary law. Gautama also covers a greater number of topics than his predecessor, even if briefly, and it may be that topics three to eight loosely follow cognate material in the Arthaśāstra :

According to Olivelle’s dating of the Dharmasūtras (2000 ), Baudhāyana is later than Gautama, but with respect to vyavahāra , Baudhāyana seems rather more primitive. For instance, he only uses the term vyavahāra to refer to the legal status of one who has obtained “vyavahāra ” (2.3.36), rather than in reference to litigation itself. Regarding litigation, he is really only concerned with Brahmanical exemptions from punishment (1.18.17–1.18.18) and murder (1.18.19–1.19.6), and in both topics he demonstrates a notable admixture of prāyaścitta (“penance”).

The Vasiṣṭha Dharmasūtra , which in its present form postdates the Mānava Dharmaśāstra , is aware of “the vyavahāras ” as rules for litigation (16.1), yet does not present substantive rules of the vyavahārapada type independently. He introduces his discussion of vyavahāra with the phrase atha vyavahārāḥ , “Now the vyavahāra s” (16.1). What follows after are two separate tracts (16.1–16.37, 19.38–19.48) covering aspects of litigation, including sections on both procedure and witnesses. His discussion of substantive law is limited, however, to a few rules embedded in a short treatment of property law (16.6–16.20) and a tract on the transfer of guilt for crimes and the miscarriage of justice (19.38–19.48). 5 In the end, perhaps Vasiṣṭha preferred the system of prāyaścitta for addressing wrongdoing rather than vyavahāra (on these two domains, see Lubin 2007 ), as he follows the last section on the king with a treatment of penances.

The Vyavahārapadas in the Dharmaśāstras

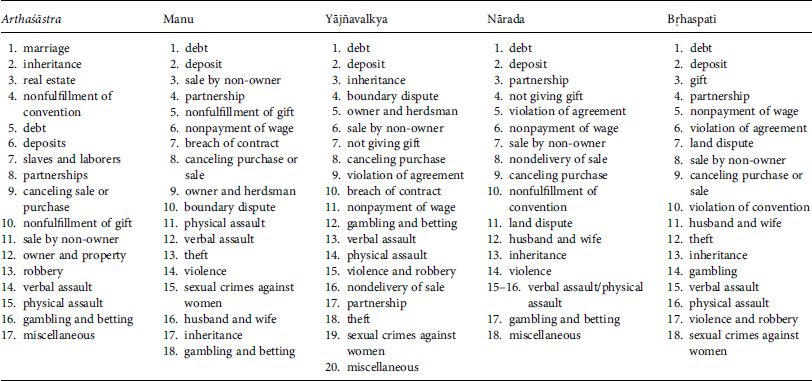

The early development of vyavahāra in Āpastamba and Gautama is carried to maturity in the Mānava Dharmaśāstra , which, as mentioned, possesses the first comprehensive presentation of the vyavahārapadas in the dharma literature. Moreover, Manu gives them this name. He drew extensively upon the Arthaśāstra (McClish 2014 ), and, in doing so, established vyavahāra as a primary concern of subsequent smṛti s. It will be useful to examine his presentation in the context of the other extant codes:

Table 23.1 Vyavahārapadas

Manu follows the Arthaśāstra closely, even if tending to treat topics more briefly, but he introduces several important innovations. First, he begins with ṛṇādāna , “nonpayment of debts,” which becomes, thereafter, the archetypal vyavahārapada for all subsequent texts. This is part of a general prioritization of economic transactions, with family law moved near the end. 6 He adds sections on svāmipālayoḥ vivāda (“dispute between owner and herdsman”; probably based on Gautama), steya (“theft”), and strīsaṃgrahaṇa (“sexual crimes against women”). He provides new nomenclature for a few titles, including the (vetanasya adāna ) “nonpayment of wage”, saṃvidaḥ vyatikrama (“breach of contract”), and sīmāvivādadharma (“the law of boundary disputes”). In addition, there are specific changes to the content of some of the vyavahārapadas , such as a greater emphasis on the rights of masters than seen in the Arthaśāstra and the treatment of sāhasa as violence rather than robbery per se.

From Manu forward, there is no dramatic change among of the vyavahārapada s themselves, although a few interesting observations can be made. First, although Manu established the eighteen vyavahārapadas , later jurists did not feel compelled to reproduce them exactly, varying somewhat in number, title, and nomenclature. Yājñavalkya, for instance, divides “canceling purchase and sale” into two separate titles and introduces the title abhyupetyāśuśruṣā , “violation of agreement,” which is picked up by subsequent writers. Both Yājñavalkya and Nārada have prakīrṇaka (“miscellaneous”) sections. All of this speaks to the great continuity of the tradition, as later writers looked back not only to earlier dharma jurists, but to the Arthaśāstra as well.

The first significant formal development among the eighteen vyavahārapada s is introduced by Bṛhaspati, who divides them into fourteen dhanasamudbhava (“arising from property”) and four hiṃsāsamudbhava (“arising from injury”) (1.1.9), which division is followed also by Kātyāyana (30). A comparison between civil and criminal law suggests itself here, but is ultimately imperfect, as the vyavahārapadas pertain always to disputes brought voluntarily by the aggrieved party. 7 From the beginning, however, it was recognized that the vyavahārapadas were not exhaustive (MDh 8.8). Nārada, who presents eighteen vyavahārapada s, argues at one point that the vyavahārapada s are, in fact, 108 in number or that “they have one hundred branches because of the variety of men’s deeds” (NSm Mā 1.20; tr. Lariviere 1989a), meaning they are in practice manifold (cf . BṛSm 1.1.13). His commentator Asahāya is yet more specific: the eighteen are divided into 132 subtypes (but, see Larivere 1989a II: 8). For his part, Bṛhaspati agrees with the number eighteen, but states that the titles rooted in injury are, in fact, threefold: each divisible into least, middle, and greatest (1.1.15). Kātyāyana is most comprehensive, arguing that the vyavahārapada s are twofold: “non-delivery of what is due” (deyāpradāna ) and injury. But, these two become eighteen-fold “because of differences in what is to be proven” and then again become 1008, “because of different kinds of evidence” (29).

Most importantly, however, Manu’s wholesale incorporation of the vyavahārapada s represents the complete identification of vyavahāra as state law with Brahmanical scripture. As mentioned before, this enhances the legal authority of the vyavahārapadas found in Dharmaśāstra over against other kinds of rules. We find in several places in the dharma literature the argument that customary law is invalid if it is opposed by sacred texts (e.g., GDh 11.20; KātSm 46; cf . MDh 8.41). That this authority comes by virtue of their inclusion within Dharmaśāstra specifically can be implied from the principle that, when there is disagreement between the two, Dharmaśāstra is to be considered more authoritative than Arthaśāstra, which, in fact, contains many of the same rules without, however, any sacred warrant (YDh 2.21; NSm Mā 1.33; BṛSm 1.1.111). While Vijñāneśvara, in his comment on YDh 2.21, argued that the two traditions were unlikely to be in conflict owing to differences in subject matter, this position cannot be sustained with respect to the vyavahārapadas , which often treat the same topics in both traditions. The supremacy of smṛti over royal edict is even suggested in a few places (NSm 18.8; KātSm 38; 668–9).

The jurisdictional changes attending the incorporation of the vyavahārapadas are, perhaps, nowhere more in evidence than in the reformulation of the “four feet” among the later classical jurists (Olivelle and McClish 2015 ). It is clear that any hierarchy of legal authority in which dharma is considered the least powerful could not be acceptable to the tradition of Dharmaśāstra. So, in the later layer of the Arthaśāstra (specifically, at 3.1.43), which was influenced by Dharmaśāstra, as well as in Nārada, Bṛhaspati, and Kātyāyana, the four feet come to be reinterpreted (see NSm Mā 1.10–1.11; BṛSm 1.1.18–1.1.22; KātSm 35–51). They are no longer treated as a set of four hierarchical legal domains, but as four means for reaching a verdict in a lawsuit. In this model, dharma refers either to an admission of guilt or trial by ordeal, vyavahāra is a trial by witnesses, and caritra /cāritra is either “inference” (anumāna ) or customary law. The most dramatic change, however, comes in the interpretation of śāsana (“royal command”), which comes to be understood as “When a king issues in a matter of dispute an order which is not opposed to Smṛtis or local usages and which is thought out as the most appropriate one by the king’s intellect or which is issued to decide a matter when the authorities on each of two sides are equally strong” (Kane III: 261). Kātyāyana gives the most detailed description among the classical jurists. He equates vyavahāra with Dharmaśāstra (36), defines customary law (caritra ) as only what agrees with the Vedas and Dharmaśāstra (46), and argues that a “lawful” (nyāyya ) royal command is one that specifically establishes a dharma not opposed by smṛti (38). Only under such circumstances, we are told (43), are each of the four feet more powerful than each earlier. The implication is that the rules of vyavahāra in the śāstra not only overrule custom, but should also govern the king’s decision, as argued unambiguously in stanzas 44–5.

There is, however, an aspirational quality to all of these claims, as we read also of contending positions, for instance that a judge should try cases so as there is no conflict between Arthaśāstra and Dharmaśāstra (NSm Mā 1.31) and that royal edicts do, in fact, nullify śāstra (AŚ 3.1.45, a late verse). Even so, the legal authority of the vyavahārapadas was undoubtedly enhanced through their incorporation into Dharmaśāstra.

Conclusion

An increased emphasis on vyavahāra defines the development of the mature dharma tradition, and yet most of the innovation in this period had to do not with the vyavahārapadas as a group but with legal procedure and specific points of law. This holds true, generally, for the commentarial literature as well.

We might conclude, then, with reference to Medhāthiti’s Manubhāṣya , where he addresses the place of vyavahāra within the greater framework of dharma , a topic mostly neglected by the classical texts and commentaries. For, vyavahāra , manifestly the most “juridical” part of Dharmaśāstra, is both continuous and distinct from the broader concept of law that informs dharma generally. In his commentary on MDh 8.1, Medhāthiti says:

Troubles are of two kinds—seen and unseen . It is a case of “seen” trouble” when the weaker man is oppressed by the stronger, who takes away by force his belongings; and it is a case of “unseen trouble” when the latter person suffers pain in the other world, through the sin accruing to him on account of his having transgressed the law…People very often act toward one another in hatred, jealousy, and so forth, and hence going by the wrong path they become subject to “unseen” evils; and thence follows the disruption of the kingdom…It is for this reason that when cases are investigated and decided in strict accordance with the ordinances of scriptures, people, through fear, do not deviate from the right path; and hence they become protected against both kinds of trouble…From all this it follows that for the sake of preserving the king, investigation of cases is necessary… (tr. Jha 1920–39 VI: 2)

He draws here a connection between wrongs suffered, wrongs committed, and dangers to the kingdom. For him, vyavahāra addresses all of them. It remediates the injury suffered by one at the hands of another, but it also prevents people and the kingdom from having to suffer the ill consequences of criminal behaviors. When vyavahāra , here understood in both its procedural and substantive dimensions, is applied diligently, the king addresses not only the injury of his subjects but also their fate in the other world, all the while supporting the well-being of his realm. Vyavahāra may be the king’s law but it serves both the worldly ends of the king and the greater salvific project of dharma .