Double-tap the image to open to fill the screen. Use the two-finger pinch-out method to zoom in. (These features are available on most e-readers.)

Of all the preserving methods, canning provides the most convenient product. Open a jar of home-canned fruit, and you have an instant dessert. Open a jar of jam, spread it on toast, and you have breakfast. Open a jar of bread-and-butter pickles, and a tuna sandwich is genius. Open a jar of chicken and stock, and you are halfway to a chicken pot pie.

Are you scared of canning? A lot of people are. Certainly there is no reason to be scared of boiling-water-bath canning. You are only going to use the boiling-water canner to seal jars of high-sugar or high-acid foods, like jams or pickles. If those foods go bad, you’ll know it because you will see the mold or taste the off-flavors, but even if you eat them, it is unlikely they will make you or anyone else sick.

Pressure canning is different. Because you are sealing jars of low-acid foods, if the time in the canner isn’t long enough or the pressure in the canner isn’t sufficient to bring the foods to 240°F (116°C), to kill off any bacteria or bacteria spores (specifically, the spores of Clostridium botulinum, which cause botulism), your home-canned foods could make people sick. What’s the solution? Follow the rules, don’t take shortcuts, and all will be well.

How big is the risk of botulism? According to the website of the U.S. Centers for Disease Control (CDC), “Home-canned vegetables are the most common cause of botulism outbreaks in the United States. From 1996 to 2008, there were 116 outbreaks of food-borne botulism reported to CDC. Of the 48 outbreaks that were caused by home-prepared foods, 18 outbreaks, or 38 percent, were from home-canned vegetables. These outbreaks often occur because home canners did not follow canning instructions, did not use pressure canners, ignored signs of food spoilage, and were unaware of the risk of botulism from improperly preserving vegetables.”

Read between the lines, and it is likely that most of those issues developed from not using a pressure canner when it should have been used. So, if you use a boiling water bath canner for your high-acid or high-sugar foods and a pressure canner for everything else, you should be fine.

Oh yeah, one small thing: wash your vegetables. The soil in which the veggies grew harbors botulism spores. But you were going to do that anyway, weren’t you?

Beyond the basic kitchen equipment you already have, most everything you will need for canning is readily available at supermarkets and hardware stores.

For processing fruits, pickles, and high-acid vegetables only. The canner is basically a large pot that comes with a lid and a wire rack to hold the canning jars off the bottom of the pot. A large one will hold nine quart jars; a smaller one will hold seven.

Yes, you can jury-rig a large pot to function as a boiling-water-bath canner as long as you can insert a rack to hold the jars off the bottom and can cover the tops of the jars with at least 2 inches of water, without the pot boiling over. I will warn you that a vigorously boiling bath can knock the jars into each other, and that is how breakage occurs. So a wire cake rack placed in the pot only does half the job, holding the jars above the bottom of the pot, but not preventing the jars from dancing around as the water vigorously boils.

The big fear among home canners is botulism. Botulism is a rare but serious illness caused by the bacterium Clostridium botulinum, commonly found in soil. C. botulinum is anaerobic, meaning it can survive, grow, and produce toxins without oxygen, such as in a sealed jar of food. This toxin can affect your nerves, paralyze you, or even kill you.

The facts are pretty simple:

For processing low-acid vegetables and meats. The canner is a specially made heavy pot with a lid that can be tightly closed to prevent steam from escaping. The lid is fitted with a petcock, which is a vent that can open and close to allow air and steam to escape from the canner. It also has either a dial or a weighted gauge to register the pressure inside the canner. Smaller pressure canners can hold one layer of quart or smaller jars, while larger ones can hold two layers of pint or smaller jars. A pressure canner can double as a boiling-water-bath canner, but a boiling-water-bath canner cannot double as a pressure canner.

Made from tempered glass in 2-quart, 1-quart, 1-pint, 11⁄2-pint, and 1⁄2-pint sizes, all of which are designed to be reusable. The USDA advises that you do not use jars in which you bought commercially prepared sauce or jam because the glass may not be strong enough to withstand home-canning temperatures and pressures. The rims of commercially used jars are sometimes thinner than those of regular mason jars, resulting in a high rate of sealing failure. If the jars seal properly and the glass doesn’t break, however, food canned in such jars is perfectly fine.

There are two major brands of canning jars in the United States: Kerr and Ball. Both brands are now owned by the same company — Jarden Corporation — and are more or less the same. European canning jars are available that seal with gaskets and metal clips. They are definitely more expensive than the usual mason jar and not terribly convenient; if you need a new gasket, you will have to order more online. I don’t have experience with that type of jar, and the USDA does not recommend them.

The typical canning jar uses a flat disk called a dome lid that sits on top of the jar and a screw ring to hold it in place. The lid cannot be reused, but undamaged screw rings can be used again and again. In years past the dome lids contained BPA, but more and more manufacturers are now producing BPA-free and phthalate-free versions. Please note that the lids do not require preheating in simmering water as they once did.

There are now one-piece lids on the market, with a very visible button that depresses when the jar is sealed. The word from the USDA is that the lids are tricky to use properly and aren’t recommended.

Canners, jars, lids — those are necessary. The following tools and utensils are not absolutely necessary but make canning much easier.

Double-tap the image to open to fill the screen. Use the two-finger pinch-out method to zoom in. (These features are available on most e-readers.)

Jar lifter. For easy removal of hot jars from a canner. Remember that in a boiling-water bath the jars will be covered with water too hot for bare hands, though the sort of insulated rubber gloves used for cheesemaking could be worn.

Wide-mouth funnel. To help in packing canning jars cleanly. (I use my canning funnel for other tasks as well — for example, when adding flour and water to my sourdough starter and when putting away leftovers.)

Plastic knife, spatula, or chopstick. For removing air bubbles from the jars.

Clean cloths. For wiping jar rims and general cleanup.

Timer. To keep track of the processing time.

A number of other home-canning accessories such as corn cutters, apple slicers, decorative labels, and special canning spoons are available. These items may simplify the process but generally are not essential.

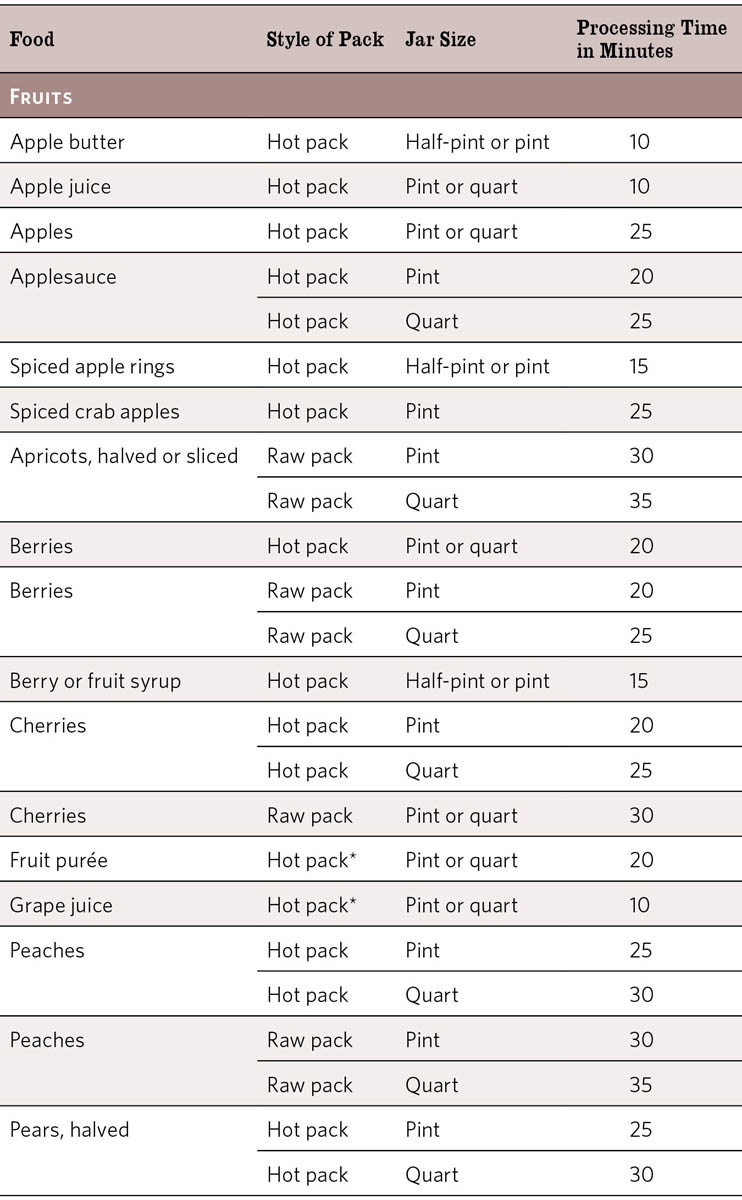

Foods can be packed into canning jars for both the boiling-water-bath and the pressure canner cooked or uncooked. Cooked food goes into the jars hot (hot pack), and uncooked (raw) food goes into the jars unheated (raw pack). The USDA recommends that the liquid that goes into raw-pack foods be heated to boiling before it goes into the jar.

Most hot-packed foods are cooked in juice, water, syrup, or stock or broth (in the case of pressure-canned meats). Tomatoes and some juicy fruits are often cooked in their own juices. Raw-packed foods are packed in a sugar syrup, fruit juice, or vinegar brine. The advantage of raw-packed foods is that the process is quicker. The advantages of hot-packed foods are that the foods are less likely to shrink and float in the cooking liquid, more food can be packed in each jar, and the food looks better. With raw packing, the canned food, especially fruit, will float in the jars. The entrapped air in and around the food may cause discoloration within 2 to 3 months of storage. Raw packing is more suitable for vegetables processed in a pressure canner.

Hot-packed foods don’t have to be cooked to death before they go into the jars. The USDA recommends heating the freshly prepared food to boiling, then simmering it for 2 to 5 minutes, before filling the jars loosely with the boiled food. This little bit of cooking shrinks the food, which allows you to pack more in, which helps keep the food from floating in the jars (there still will be some floating).

Recipes for canning in a boiling-water-bath canner or in a pressure canner will include instructions for leaving a specific amount of headspace in the jar. Headspace is the unfilled space above the food in a jar and below its lid. Typically 1⁄4 inch of headspace is needed for jams and jellies, 1⁄2 inch for fruits and tomatoes to be processed in a boiling-water bath, and 1 to 11⁄4 inches for low-acid foods processed in a pressure canner.

The wide-mouth jar is easier to pack, easier to use for fermented pickles, and safer to use in the freezer.

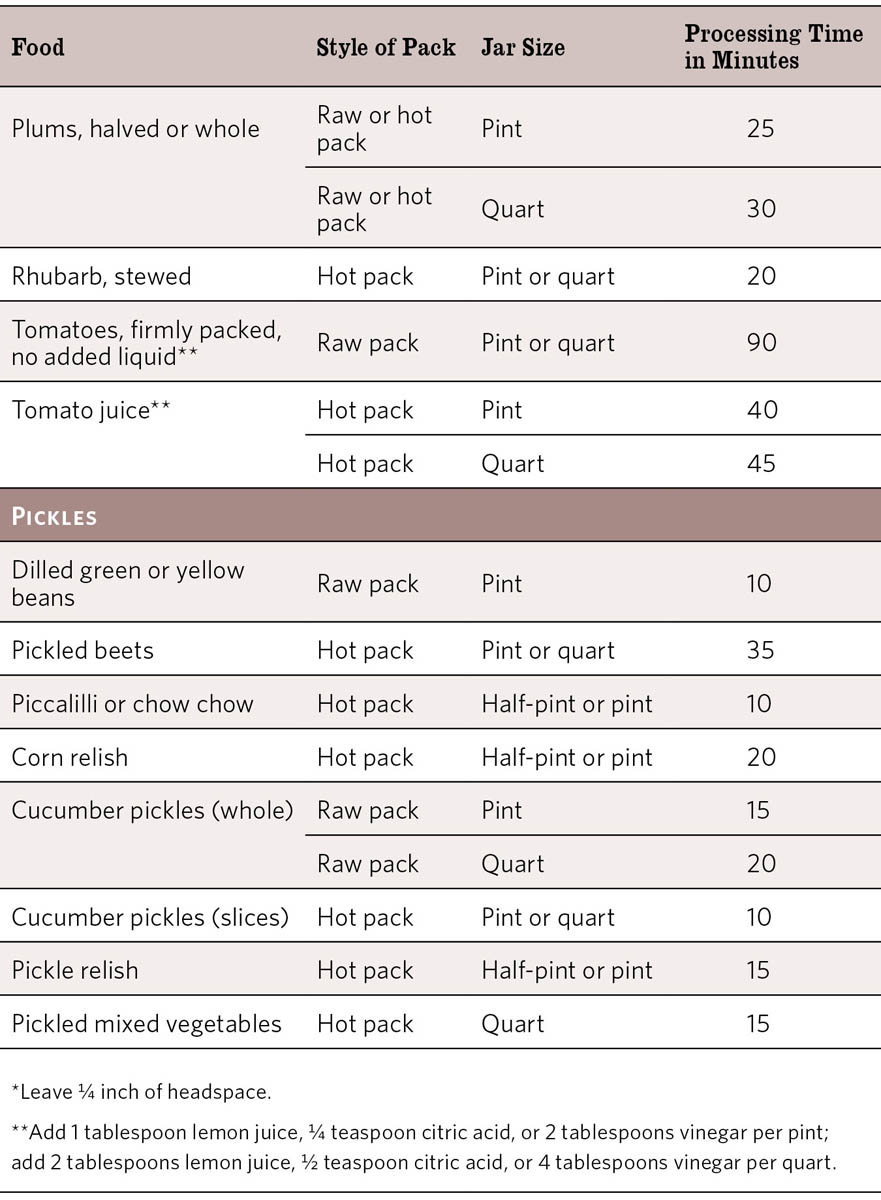

As a jar is heated in the canner, the contents expand and steam is formed, forcing air out of the jar. As the contents of the jar cool, a vacuum is formed, and the rubber compound seals to the rim of the jar. If the vacuum isn’t formed, the jar won’t seal; and leaving too much or too little headspace is the number one reason jars fail to seal. If you do not leave sufficient headspace, liquid will be forced out along with the air, gumming up the rubber seals. If you leave too much headspace, there will not be enough processing time to drive all the air out of the jar. And if a vacuum is formed but there is still a bigger headspace than required, the food at the top is likely to discolor. The discolored food is still safe to eat, but nutritional content may be decreased.

You do not have to sterilize jars used for food that will be processed for at least 10 minutes. Simply wash them in soapy water or in a dishwasher, then rinse thoroughly to remove all traces of soap.

If you are processing for less than 10 minutes, you’ll have to sterilize the clean jars: Submerge them in a canner filled with hot (not boiling) water, making sure the water rises 1 inch above the jar tops. Bring to a boil and boil for 10 minutes (or longer if you live at higher elevations; add 1 minute for every 1,000 feet above sea level). Alternatively, many dishwashers have a sterilizing cycle you can use.

Boiling-water-bath canning is a safe way to preserve high-acid foods such as jams, jellies, fruit in juice or syrup, pickles, and tomatoes. The boiling-water bath heats the contents of the jar sufficiently to kill bacteria, molds, and other spoilage organisms. During processing, air is forced out of the jars, creating a vacuum. The lid is then vacuum-sealed to the lip of the jar. As long as the jars remain airtight, the vacuum protects the food inside from harmful organisms.

Canning takes time, so do yourself a favor and undertake canning when you have a few hours with no other demands. Get yourself all set up before you begin, and the whole process becomes much easier. How much heat your stove burners put out greatly affects your time in the kitchen; a gas stove with a power burner makes a big difference.

In the instructions below, I start with prepping the food because that is often the most time-consuming step; jam, for example, may take more than an hour to cook down. On the other hand, if I am simply making pickles, for which the most time-consuming food-prep step is slicing the cucumbers, then I will start by filling my canner and getting the water hot. It’s no big deal, however, if the food is ready before the canning water is hot, or vice versa.

To peel tomatoes for canning, cut an X through the skin on the blossom end. Dip in boiling water for 30 to 60 seconds (depending on size), then immediately chill in an ice bath. The skins should slip off easily.

In the past, people were instructed to submerge the canner lids in hot water in preparation for processing. That isn’t necessary anymore; just make sure your lids are new and unused, and that you have enough screwbands on hand.

The boiling water in the kettle will be used to top off canning jars if needed for raw pack or to top off the canner if the jars aren’t covered with 1 inch of boiling water.

The canning funnel keeps the rims clean.

A magnet on a stick comes with canning sets to make setting the lids on the jars easier. It was more useful in the past, when the lids were held in hot water.

The handles of the jar rack fold over the jars to allow the pot lid to be placed on the canner.

Store the jars in a cool, dry place, with or without the screwbands. Do use the screwbands if you plan to give the jars as gifts. They are also convenient if you are going to use only some of the food in a jar and will store what’s left in the refrigerator. Do note, however, that the screwband can rust on, making the jar nearly impossible to open again; this is most likely to happen if you store your canning jars in a damp basement. Your choice.

Let the jars cool undisturbed; resist the temptation to test the seal until the jar is completely cool. If you are lucky, you will hear the distinctive “ping” of the seal happening.

At sea level, water boils at 212°F (100°C). At higher elevations, it boils at lower temperatures and therefore foods must be processed for longer times to ensure that harmful organisms are destroyed. Add 1 minute for every 1,000 feet above sea level when processing foods that require less than 20 minutes in the boiling-water bath. Add 2 minutes for every 1,000 feet for foods that must be processed for more than 20 minutes.

Unless noted otherwise, the headspace for all these preparations is 1⁄2 inch.

Double-tap the image to open to fill the screen. Use the two-finger pinch-out method to zoom in. (These features are available on most e-readers.)

Home-canned foods will maintain the best color and texture when stored in a dark, dry area where the temperature is above freezing and below 70°F (21°C). This means keeping the jars out of direct sunlight and away from hot pipes, heat ducts, gas or electric ranges, and woodstoves.

Freezing can damage the seal on a jar, resulting in spoilage. Even without damaging the seal, repeated freezing and thawing will soften the food or make it mushy. If you have no choice but to store the canned goods in an unheated area, consider insulating the jars with blankets, a very heavy layer of newspaper, or a Mylar blanket.

Canned food should never be stored in a damp area, because the dampness may corrode the metal jar lids and compromise the seals.

Of all the vegetables we grow, tomatoes are the most likely candidate for canning — because they can be canned in a boiling-water bath and because the end result is so useful in the kitchen, adding flavor or serving as the base for countless soups, sauces, stews, and casseroles. Most households can easily go through a quart of tomatoes and a quart of tomato sauce every week, or 104 quarts of tomato products each year, and that’s not even considering tomato ketchup and salsa. Here are some tips to make tomato canning easier.

Committing to pressure canning seems to be the hardest step to take in a self-sufficient homestead kitchen. The reluctance to learn how to preserve with a pressure canner seems to be related to fear of food poisoning (you are working with low-acid ingredients), expense (a pressure canner will cost at least $80 but can go upward to $300, compared to $20 for a boiling-water-bath canner), or just plain lack of experience.

There is another reason to avoid pressure canning, and that is a lack of experience with eating pressure-canned foods. Most of us were raised to appreciate that frozen vegetables are superior in color, taste, and texture to canned vegetables; this is true whether the vegetables are in a tin can or a glass mason jar. Furthermore, most of us were raised to have access to fresh and frozen meat, whenever we want it. Pressure canning was a necessity in the days when, in order to preserve meat, you had to either cure and smoke it or pressure-can it. Not only are there relatively few people who pressure-can today, but many books on canning and preserving don’t even mention it.

This leads to the question, is pressure canning a necessary skill today? I think it depends on your homesteading setup and lifestyle. Pressure canning is best for safely preserving foods that are ready to eat — the homesteaders’ MREs — in the form of soups, stews, meats in broth, cooked dried beans, cooked potatoes, and so on. The pressure canner is also useful wherever electricity for a freezer is unavailable or unreliable. Since extreme weather hits all parts of the country, pressure-canned foods can provide a necessary backup to frozen foods.

Modern pressure canners are safer and easier to use than older canners. Some have turn-on lids fitted with gaskets (the gaskets need replacing every 5 to 10 years); some have machined lids that fit together and seal with wing nuts. They all have removable racks, an automatic vent/cover lock, a petcock (also called a vent port or steam vent), and a safety release. The pressure canner may have a dial gauge for indicating the pressure or a weighted gauge for indicating and regulating the pressure, or both. Reading your manufacturer’s directions and practicing how to properly assemble your canner and how to monitor your gauge will go far in alleviating your fears.

Be aware that the gaskets in some models of pressure canners (and the dial in others) need to be checked from time to time. This was once a service provided by the local county extension office. Such offices are few and far between; if you can’t locate an extension agent to check on the safety of your pressure canner, you will have to write to the manufacturer for assistance. Or buy a new one.

Processing times are usually given for canning at altitudes of sea level to 1,000 feet. If you are canning at a higher altitude, the times remain the same, but the pressure is adjusted.

Home canning recipes assume that you’re working at sea level, or close to it. When you’re pressure-canning at a high altitude, the processing time remains unchanged, but the pressure is adjusted.

Although the pressure canner relies on steam rather than water, it may take longer to bring the pressure canner up to processing temperature than you expect. For safe processing, the canner needs a “venting” period, during which air and steam escape at full blast for at least 10 minutes before you start the actual processing. Don’t set your timer for the 10-minute venting period until you see a large plume of steam venting (as opposed to a small wisp of steam).

Some foods are processed at a higher pressure than others, so check the chart to know how to set the counterweight on the valve or how much pressure to maintain. The first couple of times you use your canner, you may have to fiddle with the heat a bit to maintain the proper pressure.

Before you start canning, be sure your pressure canner is in good shape. Don’t worry about discoloration on the inside of the canner; that is normal. If your lid has a rubber gasket, make sure it fits properly and is not cracked. This rubber seal usually comes prelubricated, but if it feels a bit dry you can apply a light coating of cooking oil around the ring. Also check that the black overpressure plug on the cover is not cracked or deformed.

Once the jar is filled, remove any air bubbles by running a chopstick or bubble tool (comes with canning kits) around the inside edge of each jar. Wipe the rims clean before placing on the lid and screwband. Lightly tighten the screwband.

The pressure canner comes with a rack to hold the jars above the bottom of the pot. They will sit in a few inches of water. Use the jar lifter to safely move the jars into place.

Once the water in the pressure canner begins to boil, vent the air for a full 10 minutes.

Start timing only when the proper pressure has been reached. Keep an eye on the dial gauge to be sure you are maintaining the proper temperature.

Processing times do not vary according to altitude, but pressure does. This table is for foods being processed at an altitude of no more than 1,000 feet above sea level. At that altitude, process at 11 pounds per square inch (psi) in a canner with a dial gauge or 15 psi in a canner with a weighted gauge. Headspace is 1 inch unless indicated otherwise.

The warranties on some stovetops made of glass or ceramic are voided if the stovetop breaks or cracks when you use a canner on it. On other stoves, there is a sensor that prevents breakage but therefore does not allow the burner to maintain an even temperature high enough for canning — that is, high enough to kill all the bacteria that may be present in the food being canned.

For safety, you need a flat-bottomed canner no bigger than the diameter of your burner. The website PickYourOwn.org has good information regarding the safety of canning on glass and ceramic stovetops, including specific makes and models of stoves and what you can or cannot do on them without voiding their warranties.

In almost every workshop I teach, someone offers that his or her mother or grandmother has been reusing canning lids since forever. There is also a lot of chatter on the Internet about old-fashioned methods of canning that worked for Grandma. Will they work today?

I don’t run into a lot of people who can meat. Those folks who come from a meat-canning tradition are usually hunters, which makes sense if you think about it. Homesteaders who raise animals often get their meat butchered and frozen at a slaughterhouse, or they raise chickens in batches that fit their freezer’s capacity. Hunters come home with large animals that have to be dealt with immediately — and packing a home freezer with a huge load of fresh meat is unsafe. But there’s no limit to how much meat you can can.

One reason given for canning meat is that it is convenient to have already-cooked meat in the pantry. Yes, it is convenient, but canned meat should always be cooked at a boiling temperature for 15 to 20 minutes before it’s consumed, according to the USDA. That makes the idea of, say, making chicken salad from a jar of canned chicken a lot less convenient. The most compelling reason to can meat is that canned meat won’t be ruined in the event of a power failure. The reason not to can meat? You end up with a boiled meat product that is a challenge to use. I’m all for canning meat that will be “boiled” (simmered) in tomato sauce — as meatballs or as chili, for example. And I’m all for boiling canned chicken in broth. Beyond that, my imagination fails me.

It should go without saying that the only way to safely can meat is in a pressure canner, according to the times established by the National Center for Home Food Preservation, a division of the USDA. And it is necessary to follow all the steps listed in Step-by-Step How to Pressure-Can for safe pressure canning.

I am not an expert on canning meat. The following are tips I have gleaned from the instructions with my Presto pressure canner and from the National Center for Home Food.

After a jar has been processed in a boiling-water-bath or pressure canner, it should be sealed. If the seal is faulty, the food inside the jar is not spoiled, but it won’t keep long. Store unsealed jars in the refrigerator and use within a week.

To test for a seal:

The lid should not “give” or move.

Hold by the lid only.