Cover foods drying outdoors with nylon netting to protect from insects and birds.

Drying is one of the oldest methods of preserving food. It is relatively easy to do, and though it takes time, your attention is not required continuously. Drying preserves much of the vitamins and minerals that would be lost by canning. In warm climates, you can use the drying power of the sun directly or in solar dryers; in more humid climates, there are indoor ovens and electric food dehydrators. Because drying removes moisture, the food shrinks in volume and becomes lighter in weight, reducing the amount of space you need for storage.

Drying as a food preservation technique has undergone different waves of popularity as people learn of new ways to make enhanced dried food snacks. Fruit leathers probably date back to the sixteenth century, but they have become popular as a homemade snack only since the advent of electric home dehydrators. In recent years, dried veggie chips as snacks have boosted the popularity of food drying. The veggie chips on the market tend to be extremely expensive, so making your own makes sense whether you are dealing with garden surpluses or just want to provide healthful snacks.

Drying preserves food because bacteria, yeast, and molds can’t grow in a dry environment. Drying also slows down the action of the enzymes that spoil food (these naturally occurring substances also cause foods to ripen). When you want to use dried foods, you can either snack on them directly (dried fruit and beef jerky) or reconstitute them (add back the water) and cook as you would fresh food. Stored in a cool, dark, dry spot, dried food should keep its quality for anywhere from several months to 2 years.

There is a bit more to drying than you might think, if you are going for quality. Most vegetables should blanched before they are dried. Light-colored fruits should be treated with ascorbic acid to preserve their color. Finally, some fruits and vegetables should be pasteurized (heated or frozen) to make sure all the spoilage organisms are destroyed.

I live in the Northeast, where fall weather is likely to be rainy, so outdoor drying is pretty much out of the question. I get the most use out of my dehydrator when my son goes foraging for wild mushrooms; in fact, I think drying is the ideal preservation method for mushrooms. I love seasoned dried kale chips and sweet potato chips, but they take forever to dry and the dried chips are eaten faster than I can reasonably produce them. I do dry tomatoes on occasion, and I make beef jerky. I have dried all sorts of vegetables, just to experiment with them, but I prefer the convenience of freezing to just about every other preserving method. Many fruits and vegetables require a quick blanching in boiling water to preserve their color and texture. Once I’ve done that, I lean toward freezing just so I can wrap things up and move on.

If you are serious about dehydrating, my advice is to build or buy as large a dehydrator as possible. Otherwise, the process is very, very slow, and you have to focus on keeping your vegetables in good quality before you can dry them.

You can dry food in the open air, in a conventional oven, or in an electric or solar food dehydrator. There are pros and cons to each method.

A hot, breezy climate with a minimum daytime temperature of 86°F (30°C) is ideal for drying fruit outdoors in the sun. But if the temperature is too low or the humidity too high, the food may spoil before it is fully dried. The USDA doesn’t recommend drying meat and vegetables outdoors because these foods are too prone to spoilage.

Woven baskets have been used for outdoor drying for centuries, but a screened tray is probably more efficient, if less attractive. Avoid galvanized metal, aluminum, or copper screens, which can impart off-flavors or even potentially toxic salts to the food. Top-quality food-drying screens are made from food-safe plastic screening and are available online. Cover the fruits and vegetables on the trays with cheesecloth or nylon netting to help protect them from birds and insects. Direct sunlight destroys some of the more fragile vitamins and enzymes and causes the color of the food to fade, so you will have better results if you can shade the foods with a dark sheet of cloth or metal. Indoors, it is easy to use screened trays placed on chairs or sawhorses. No further equipment is needed.

Cover foods drying outdoors with nylon netting to protect from insects and birds.

If you want to go really low-tech, and you have the climate to make it possible, dry food by draping it over branches or spreading it on wide shallow baskets on a roof. Or thread pieces of food on a cord or a stick and hang it over a fire or woodstove, or from the rafters. Bundle herbs and suspend them from doorknobs or nails in rooms with good ventilation. You can also place screen doors across chairs for use as drying screens, or make shallow baskets of sheets hung between clotheslines outside, or in the attic or an upstairs room with screened windows wide open.

Anything that was dried outdoors — in the sun or on the vine — may be harboring some insects and their eggs. Pasteurizing the dried food will help you avoid having those insects eating your dried food. To pasteurize in the freezer, seal the dried food in freezer-type plastic bags. Place the bags in a freezer set at 0°F (–18°C) or below and leave them for at least 48 hours. Alternatively, you can arrange the dried food on trays in a single layer. Place the trays in an oven preheated to 160°F (70°C) and leave for 30 minutes. After either of these treatments, the dried food is ready to be conditioned and stored.

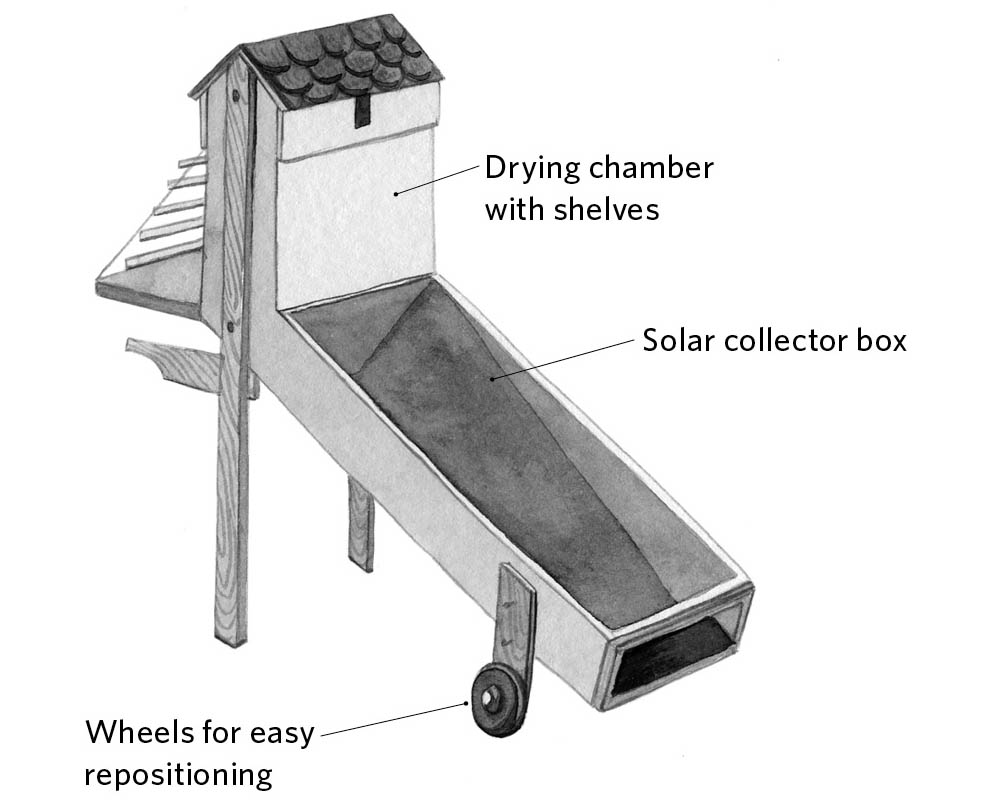

Highly effective, solar dryers yield results on par with electric dehydrators, without the expense and carbon footprint associated with using electricity. Solar dryers don’t require a low-humidity climate, though they do require sunshine and high temperatures. The only downside is the requirement that you assemble or build your own dryer. There are plenty of kits and designs available online. In rainy climates, look for a dehydrator that can be brought indoors and used with electricity to finish the job.

A solar dryer has three basic parts: a solar collector (such as an old storm window), a box to hold the food, and a stand. The collector captures the heat of the sun to warm air that will circulate around the food. The box is usually made from plywood and holds food trays, which are made from screening to allow greatest air circulation. The most sophisticated solar designs include adjustable vents and thermostats.

You can use the oven in your kitchen to dry foods, but there are several drawbacks: air circulation in a conventional oven tends to be poor, even with the oven door propped open and a fan placed nearby to improve ventilation, so results can be uneven. Also, the process ties up the oven for a long time and is not particularly energy efficient. However, this method requires no new equipment and can be done in any climate. It is the equipment of choice for making beef jerky, which requires a slightly higher temperature than other dried foods. It does a reasonably good job on tomatoes. I would think that convection ovens (which have fans to circulate the air) would do a slightly better, faster job than nonconvection ovens, but I can’t use my convection feature for temperatures under 300°F (150°C).

To use an oven to dehydrate food, you must be able to set the oven for 140°F to 170°F (60°C to 80°C). At higher temperatures, the food cooks rather than dries. Your drying racks should be 3 to 4 inches shorter than the oven from front to back. Wire cooling racks placed on top of cookie sheets work well for some foods. Set the oven racks that hold the trays 2 to 3 inches apart for good air circulation.

Whatever method you’re using, 12 square feet of space can accommodate about a half bushel of produce for drying.

Electric dehydrators give excellent and consistent results. The only downsides are the cost of buying and running the appliance, the limited amount of food that can be dried at one time in most home models, and the storage space the appliance requires when not in use. If you want to do a lot of drying, buy as large a unit as you can afford; the smaller units can be frustrating to use.

A food dehydrator has an electric element for heat and a fan and vents for air circulation. Dehydrators are efficiently designed to dry foods quickly at 140°F (60°C). They are widely available in stores and online. Costs vary widely, depending on the features of each model. The most expensive and efficient ones have stackable trays, horizontal air flow, and thermostats.

Most electric dehydrators have limited rack space for drying.

Not all vegetables can be treated the same, so be sure to check the drying chart for specific times and whether step 2 (blanching) is even necessary. Beans can be left to dry on the vine (see Vine-Drying Beans), though they may need to be finished off in a dehydrator and should be pasteurized (see Pasteurizing Fruits and Vegetables Dried Outdoors).

A mandoline does the best job of slicing vegetables thinly for even drying.

Blanching sets the color and texture of some vegetables.

Adding oil to veggie chips will help seasonings adhere.

Pieces on drying trays can start out touching; shrinkage is considerable.

A surplus of cucumbers and a shortage of time are both fairly standard problems for vegetable gardeners. Here’s a tip from Kathy Harrison, author of Just in Case, Another Place at the Table, and One Small Boat. She slices her cucumbers 1⁄4 inch thick, then dries the slices until crisp. When she wants pickles, she makes up a small batch of hot brine (you could reuse brine, if you want to), adds the dried cucumbers, transfers it all to a jar and tucks it in the refrigerator. The next day, she has a jar of pickles ready to eat, crisp ones at that.

Although all vegetables can be dried, not all vegetables are appealing once dried. For example, Brussels sprouts have a strong flavor once dried; dried cabbage absorbs moisture from the air and is prone to mold; and lettuce, summer squash, and cucumbers are too high in water content to be dried. So the following chart includes only vegetables that are reasonably appealing when dried. Drying times may vary. Experiment with slicking the vegetables in oil and seasoning before drying.

Double-tap the image to open to fill the screen. Use the two-finger pinch-out method to zoom in. (These features are available on most e-readers.)

In the proper climate, it is possible to dry all vegetables without any preparation whatsoever, but the quality is really improved by blanching, which stops the enzyme action that could cause loss of color and flavor during drying and storage. It also shortens the drying and rehydration time by relaxing the tissue walls so that moisture can escape and later reenter more rapidly. Cutting the vegetables into small, thin pieces improves quality by reducing the drying times.

To dry beans (navy, kidney, butter, black, great Northern, lima, soybeans, and so on), leave the bean pods on the vine in the garden until the beans inside rattle. When the vines and pods are dry and shriveled, pick the beans and shell them. No pretreatment is necessary. If the beans are still moist, the drying process is not complete and the beans will mold if not more thoroughly dried. If needed, drying can be completed in the sun, in an oven, or in a dehydrator. Dried beans should be pasteurized (see Pasteurizing Fruits and Vegetables Dried Outdoors) before being stored.

Like dried fruit, seasoned dried veggie chips are as much about snacking as they are about preserving. But while the sweetness and the chewiness of fruit slow down the snacking, the saltiness and crispiness of veggie chips invite you to eat them as fast as you can make them. Still, they are a nutritious alternative to fried potato chips and corn chips, and well worth making.

Seasoned chips can be made in the oven or in a dehydrator. Depending on how low a temperature an oven can be set to, chips in the oven take about half as long as chips in a dehydrator.

The vegetable needs to be sliced as thinly and evenly as possible, which makes this a job for a mandoline. You can use a food processor if you have a thin-slice disk. The pieces should be no more than 1⁄8 inch thick. Whether or not to blanch the veggies first is up to you; I prefer fully cooking beets and blanching green beans. Sweet potatoes should be raw. Slick the vegetables with any vegetable oil and season with salt, garlic powder, onion powder, or dried green herbs, such as rosemary or oregano. Cinnamon or a cinnamon-sugar mix can also be used. I stay away from spices that have bitter notes, such as curry.

Arrange the veggie chips on lightly oiled baking sheets or dehydrator sheets and dehydrate until crisp. Timing varies, depending on the vegetable.

Makes about 8 cups

Any type of kale can be used, but I have a slight preference for lacinato kale because it is flatter and fits better in the narrow space between trays in the dehydrator. Don’t overdo the salt; the kale doesn’t require a lot. Although not quite as wonderful as freshly roasted kale, these dried ribbons of kale are tasty and compelling. The kale should be washed and well dried before you start.

Makes about 6 cups

You don’t have to peel the sweet potatoes first, though you can if you want.

Dealing with a surplus of fruits by drying is a no-brainer. Dried fruits are the original snack foods, and we all love to snack. While dried vegetables require seasoning to shine as snacks, fruits are so inherently flavorful that no additions are really needed. However, fruits that darken when exposed to air will benefit from a dip in an ascorbic acid solution, and some fruits also benefit from being blanched in a sugar syrup (see Syrup Blanching: An Optional Step).

Check the drying chart on the right for specific drying times for each type of fruit. Many light-colored fruits, such as apples, peaches, and bananas, darken rapidly when cut and exposed to air, but you can dip the fruit in an ascorbic acid (vitamin C) solution to prevent browning. Ascorbic acid is available in powdered or tablet form from drugstores or grocery stores. Because of the high concentration of sugar in dried fruit, fruit is more prone to mold than vegetables. Before storing dried fruit, condition the fruit (step 4) to equalize the moisture among the pieces and check to see if additional drying is necessary.

Syrup blanching sweetens the fruit (obviously), fixes the color, and makes tart dried fruit more palatable. It also takes time and adds sugar and calories, which undermines some of the health benefits of the fruit. Syrup blanching works best with apples, apricots, figs, nectarines, peaches, pears, pie cherries, plums, and rhubarb.

To make the syrup, combine 11⁄2 cups sugar and 21⁄2 cups water in a pot. Bring to a boil, stirring until the sugar dissolves. Add 1 pound prepared fruit and simmer for 10 minutes. Remove from the heat and let the fruit steep in the syrup for 30 minutes. Then lift the fruit out of the syrup and rinse lightly in cold water if desired (rinsing makes the fruit less sticky). Drain on paper towels before drying.

Drying times vary a lot depending on the efficiency of the dehydrator, the juiciness of the fruit, and the size of the pieces. Syrup-blanched fruits take longer to dry than fruit that hasn’t been blanched.

Fruit leather is a tasty, chewy way to enjoy fruit. It’s made by pouring puréed fruit onto a flat surface for drying. The fruit you purée can start as fresh, canned, or frozen. When dried, the fruit is usually rolled up. It gets the name “leather” because it has the texture of leather.

Is it dry yet? That is the money question. If the dehydrated food harbors moisture, it is prone to going moldy. In general, it is better to overdry than underdry, but if you allow the food to become too dry, it will crumble to dust. Drying times are given as a range. After you hit the minimum time, begin testing. Let a few pieces cool to room temperature for a few minutes, then bite into them. Here’s how to tell if they’re dry enough:

People have been drying meat into jerky in the open air and in dehydrators for years, centuries really. But there are risks with both methods because the meat is never brought to 160°F (71°C), the temperature you need to destroy all the harmful bacteria (the maximum temperature of most dehydrators is 145°F/63°C). The USDA currently recommends cooking the meat first to 160°F (71°C), then drying. The method I use, which I describe below, is neither traditional nor officially sanctioned by the USDA. Instead, I slowly cook/dry the meat at 225°F (107°C), resulting in jerky that I know is safe in just 3 to 4 hours.

When we think about jerky, we usually think of beef jerky, but any very low-fat meat can be made into jerky, including venison and white-meat turkey. The beef cuts most often turned into jerky come from the round. A whole beef round consists of three major muscles: top round, eye of round, and bottom round — all of which are excellent jerky choices. The top round is often cut into round steaks 1 to 11⁄2 inches thick to make London broil, which is the cut recommended by many for making jerky. Flank steaks are also good to use. Whatever meat you use should be as lean as possible. It takes about 4 pounds of fresh, raw meat to make 1 pound of dry jerky.

You can change up the spices used and make your own Spicy Beef Jerky. But really, the seasonings are up to you. Be aware that flavors, particularly salt, will concentrate as the meat dries, so don’t go overboard. Using curing salts will enable you to safely store the meat at room temperature, but they aren’t necessary if you refrigerate the jerky.

Trim off as much fat as you can.

Slice with the grain.

Marinate for 3 to 24 hours in the refrigerator.

Drying in the oven at 225°F (110°C) prevents spoilage.

Makes about 8 ounces

You can play with the seasoning mix as you like. This version is pretty spicy, so unless I am making it for hotheads, I cut back on the chipotle or the hot paprika, or both. My son calls my less-spicy versions “primitive.” He explains himself this way: “When you cut back on the spice, you really taste the meat — and it is really meaty meat . . . what I think the cowboys must have kept in a shirt pocket to eat on the range.”

Cool dried foods completely before packaging them for storage in clean moisture-resistant containers. Glass jars, metal cans, or freezer containers with tight-fitting lids are good storage containers. Plastic freezer bags are acceptable, but they are not insect- and rodent-proof.

Dried fruits and vegetables should be stored in a cool, dry, dark place. Most dried fruits can be stored for 1 year at 60°F (16°C), or 6 months at 80°F (27°C). Dried vegetables have about half the shelf life of fruits. Fruit leathers should keep for up to 1 month at room temperature. Jerky, as previously noted, should be stored in the fridge and will keep for up to 2 months. To store any dried product longer, keep it in the freezer.

Dried fruits can be eaten as is or reconstituted. Unseasoned dried vegetables usually are reconstituted. Once reconstituted, dried fruits or vegetables are treated as fresh. Seasoned vegetables, fruit leathers, and meat jerky are eaten as snacks, as is.

To reconstitute dried fruits or vegetables, add water to the fruits or vegetables and soak until the desired volume is restored. For soups and stews, add the dehydrated vegetables without rehydrating them; they will rehydrate as the soup or stew cooks. Also, leafy vegetables and tomatoes do not need soaking. Add enough water to cover, and simmer until tender.

Tomatoes are easy to dry — and easy to use. Just soak the dried tomatoes in warm water for 30 minutes and they will become soft and pliable, ready to add to soups, sauces, casseroles, and quiches. (Reserve the soaking liquid to add flavor to stocks and sauces.) Once reconstituted, use dried tomatoes within several days or pack them in olive oil and store in the refrigerator for up to 2 weeks.

To use oil-packed tomatoes, drain the tomatoes from the oil and use. Keep the tomatoes left in the jar completely covered with olive oil, which may mean adding more oil as you use the tomatoes. Add a sprig of basil and a clove of garlic for extra flavor, if you like. Don’t toss out that oil when you’re done with the tomatoes. It will pick up flavor from the tomatoes and be delicious in salad dressings or used for sautéing.