A small country sandwiched between the two main belligerent powers of the First World War, in 1835 Belgium had embarked on the construction of an extensive railway network, just five years after the country had won its independence. By 1914 the network included some 4400km (2700 miles) of main line, backed up by around 4000km (2500 miles) of branch lines. Its sovereign territory was invaded on 4 August 1914, and the armoured trains (constructed primarily for the defence of Antwerp) would play a significant role in the conflict, as much from a psychological viewpoint as from their military impact. And this especially when one compares their numbers and their actions with the size of Belgium. The railway troops were formed in 1913, as an integral part of the Corps of Army Engineers, but the notion of ‘armed trains’ had been considered as far back as 1871, and the concept had been the subject of courses at the Belgian War College.1

The railway war was considered to be first and foremost defensive in nature, involving the destruction or blocking of numerous tunnels, and the cutting of bridges in the provinces directly menaced by an enemy attack, while at the same time seeking to avoid obstructing the movement of one’s own troops. ‘Phantom’ (or ‘ram’) trains would be sent to crash into enemy trains or crucial elements of infrastructure such as turntables, in order to block the free circulation of enemy traffic.

In September 1914, the decision was taken to link together the different forts around Antwerp by a single track circular rail line. The construction of the line took from 7 September to 1 October. In particular it would allow the movement of armoured trains during the final days of the siege.

Four Light Armoured Trains, for patrol and protection duties, were ordered by the Army High Command, and were constructed out of metal sheets meant for ship construction in the Antwerp North workshops with the aid of the Engineers’ Railway Company (CFG2). They were to be followed by three Heavy Armoured Trains, to be armed with naval guns provided by the British, to act as mobile artillery in advance of the line of forts.

The first Light Armoured Train was completed in ten days, the second in eight days and the third in just six days. The fourth train, however, was captured incomplete when Antwerp fell to the German Army.

The first train (No 1, Light, commanded by Lieutenant Michel then, when he was wounded, by Sub-Lieutenant Goutière) became operational on 5 September and was in action3 continuously right up to 8 October, in particular on 25 and 26 September 1914 when it supported the operation to block the Brussels-Tournoi line, by means of ‘phantom trains’ launched in the direction of Enghien and Hal. This operation was repeated on 7 and 8 October, when the target was Duffel. In addition to their normal ammunition load of 12,000 rifle cartridges, 240 shrapnel shells and 120 57mm HE rounds, the armoured trains also carried 25kg (55lbs) of explosives for blowing up key installations.

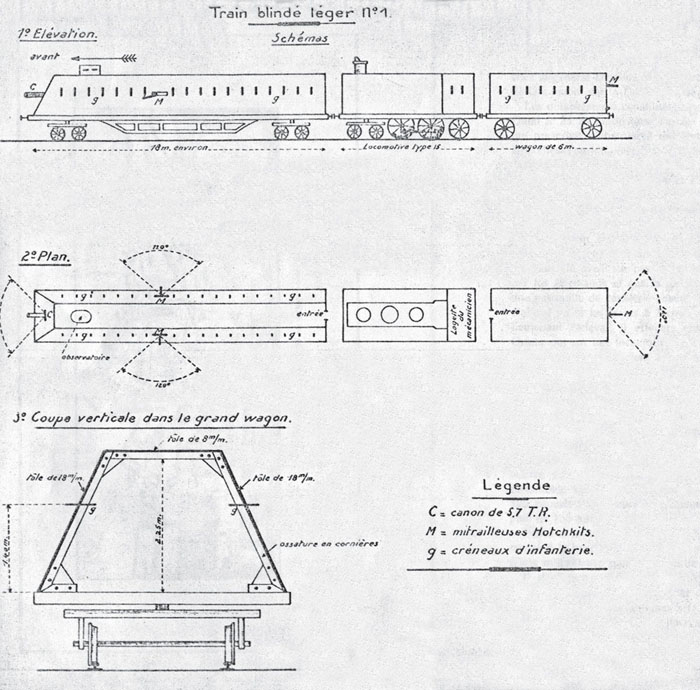

The only known plan of the Light Armoured Trains. Although schematic, it gives a good idea of the overall dimensions on the one hand, and of the layout of the armament (a 57mm chase gun firing straight ahead and three machine guns, including one firing to the rear). We have never seen a photo of the four-wheel van.

(Drawing: Bulletin belge des sciences militaires, July 1932)

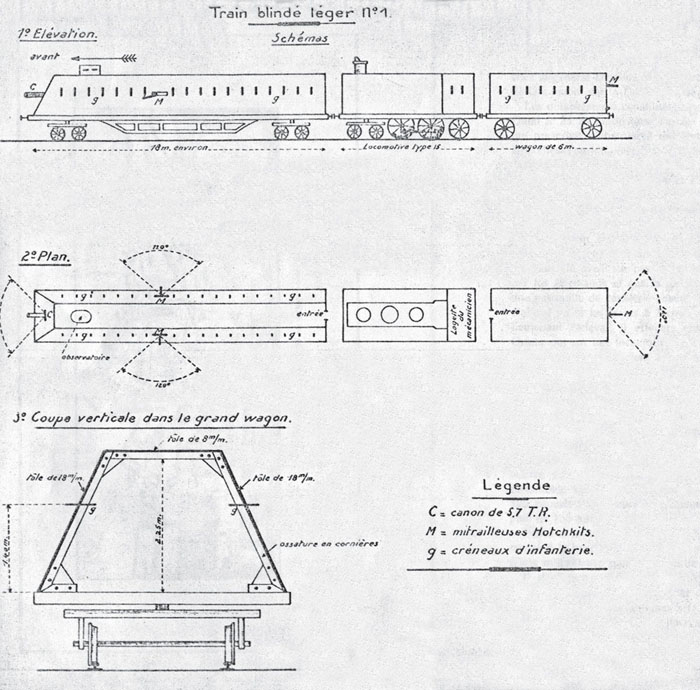

Class 16 armoured engine. These 4-4-2 tank engines were among the most modern of their day.

(Photo: Paul Malmassari Collection)

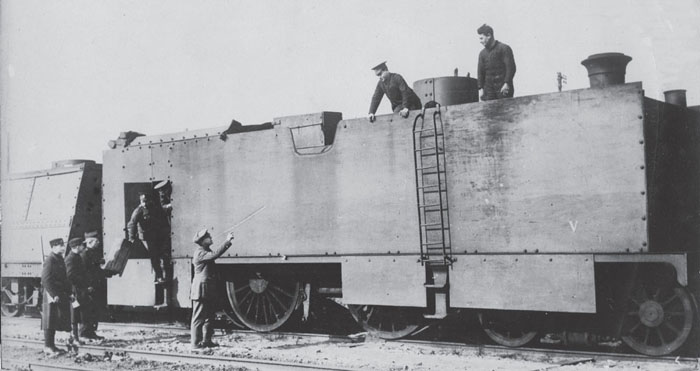

The other type of engine used with the Belgian armoured trains, the Class 32 Etat, an 0-6-0 tender engine also used on French railways.

(Photo: Paul Malmassari Collection)

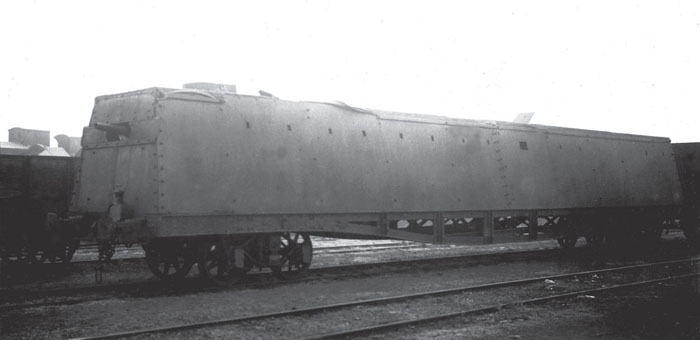

Armoured wagon of a Belgian Light Armoured Train. The chase gun is a 57mm QF model on a casemate mounting with a severely restricted field of fire, its embrasure closed by sliding shutters. Of the three machine guns on the train, one fired to the rear from the van at the tail of the train. Each wagon carried six rails 6m (19ft 8in) long, ten pairs of fishplates and repair gear.

(Photo: Paul Malmassari Collection)

Armoured Train No 2 (commanded by Lieutenant Deleval) went into action for the first time between 11 and 14 September, along with Armoured Train No 1. It participated in the destruction of the bridges at Denderleeuw and Alost on the River Dendre. It then operated on several occasions at Alost, Renaix and Audenaerde, at Eine and Zingem, at Tielt, and at Deurle. On 8 October, the crew launched phantom trains from Mortsel in the direction of Lierre.

Despite these actions, the German advance forced the Belgian Army to retreat. It entrenched itself in the fortified stronghold of Antwerp, from which the armoured trains also stationed there took part in sorties, in particular that of 9 to 13 September towards Vilvorde, Louvain and Aarschot. On 7 and 8 October, a violent bombardment struck the fortress, but it held firm, allowing the evacuation of an enormous quantity of stores and virtually all the troops. On 9 October, the last Belgian and British troops pulled out, heading west. On that date, the unfinished Armoured Train No 4 was abandoned in Antwerp and captured. The demolition of the railway bridge at Boom cut off the retreat of Light Armoured Train No 1, which was sabotaged by its crew who were evacuated on Armoured Train No 2. They reached Ostend on the evening of the 9th, and formed the crew of Armoured Train No 3 which had been evacuated to Ostend the day before. The two surviving armoured trains were sent to Dunkirk on 13 October 1914. Then on the 19th, Armoured Train No 2 returned to Dixmude. Its crew were then employed in repairing the lines, notably on 21 and 22 October, in order to re-establish the rail link on the Caeskerke-Nieuport line.

Close-up of the armoured bogie wagon of Armoured Train No 1 after its capture by the Germans. Note the armour protection for the bogies and the buffer beam, which now has no buffers. It is uncertain whether this modification was carried out by the Belgians or the Germans. In addition, although the armament is not in evidence, the horizontal sliding armoured shutters have been removed, giving way to a much larger embrasure opening.

(Photo: Paul Malmassari Collection)

One of the results of a ‘phantom train’ launched against German rail transport. The CFG driver and fireman of the ram engine jumped to safety before the collision and were only slightly injured. They were both later decorated by King Albert.

(Photo: All Rights Reserved)

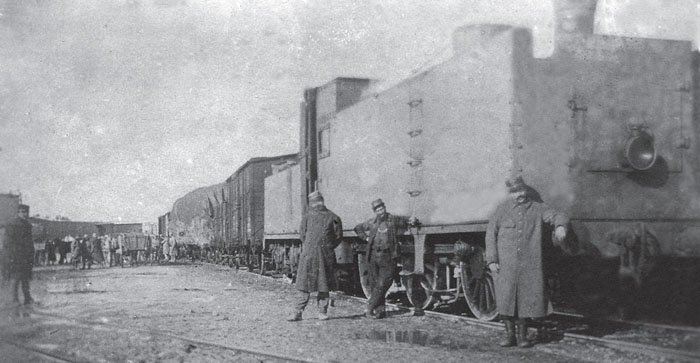

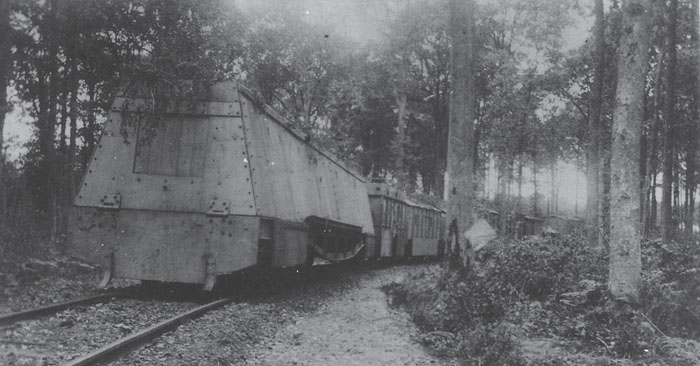

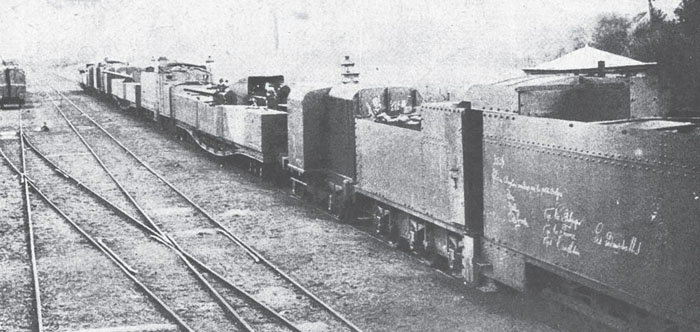

A Belgian Light Armoured Train following its capture by the Germans near Boom. It was subsequently used by them for some time, as shown by the postcard below.

(Photo: Paul Malmassari Collection)

This postcard is in fact German, showing PZ No 1. The armoured van on the left is the one seen in the background in the two photos above, indicating that the Germans rearranged the order of the train units, as the engine now brings up the rear.

(Postcard: Paul Malmassari Collection)

Here on the left one can just make out the rear of the artillery wagon with its larger embrasure.

(Photo: Paul Malmassari Collection)

Class 32 engine captured at Antwerp.

(Photo: Paul Malmassari Collection)

Another captured Class 32 engine. Note the armour plating which extends much lower than is seen on other engines in service, together with the inspection hatches.

(Photo: Paul Malmassari Collection)

The role of the Belgian Light Armoured Trains came to an end in late October 1914. The two trains were sent back to Calais where their armour protection was removed, apart from the armour on one Class 32 engine used to haul a British heavy railway gun, and on two armoured engines allocated to the French 200mm artillery battery ‘Pérou’.4 There was also a special train armed with a 21cm mortar originally mounted in the Blauwgaren Redoubt, double-headed by two armoured engines, which was in action during the battle of the Yser.

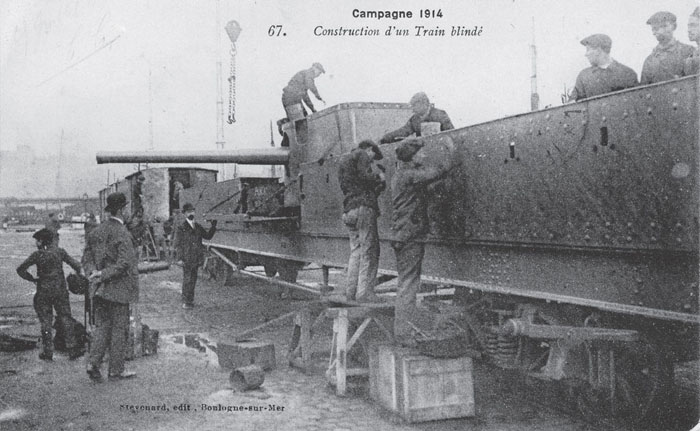

From 8 September 1914 the construction of these three trains in Antwerp was entrusted to Lieutenant-Commander5 A. Scott Littlejohns, who was acting as attaché to General Deguise, the Military Governor of Antwerp. This co-operation resulted in the trains often being referred to as ‘Anglo-Belgian Armoured Trains’, notably in the newspapers of the day. Some days earlier, it had been agreed to cede to the Belgian Army several British naval guns, which were the only ones capable of counter-battery fire against the German artillery.

Of the three trains planned,6 two were constructed in the Hoboken workshops (by the British Engineering Company) and the third in the North Antwerp workshop. The first two were armed with three 4.7in (120mm) naval guns and armoured from the outset. Each train was composed of three Class 32 or 32S Etat Belgian engines (of which one could be detached for track reconnaissance), three 40-tonne artillery platform wagons 18m (59ft) long, and three Bika Type vans. The mixed nationality crews comprised one Royal Navy officer and six senior gunnery ratings, seventy NCOs and gunners from the Belgian fortresses, and finally railway personnel of the CFG. The armament of the third train was to comprise two heavier 6in (152mm) naval guns without shields, which at first were simply bolted onto unarmoured platform wagons (one with girder chassis underpinnings and the other with bar-type chassis underpinnings).

The first armoured wagon was completed on 15 September7 and its firing trials were successfully carried out the same day. The next ten days were spent fixing the armour protection in place, training the crews and reconnoitring the railway lines and the Belgian positions. On the 23rd, the first train with one armoured wagon left Antwerp at 11.00, carrying Lieutenant-Commander Littlejohns who was the overall commander of the Heavy Armoured Trains, Captain Servais, French and Belgian officers, and the British Military Attaché. An observation aircraft was to correct the fall of shot on the German batteries which were thought to be in Epperghem. In spite of the mist which interfered with observation, based on the interrogation of prisoners and refugees the shoot actually took place.

From their base in Antwerp, the first two trains went into action at Malines between 24 and 27 September, co-operating with spotting aircraft and balloons. One of the trains was even able to approach within 1800m of the German lines. On the 28th and 29th, they were in action in front of Forts Waelhem and Wavre-Sainte-Catherine (Sint-Katelijne-Waver), as the guns of the forts were unable to reach the German batteries. At one point, a German 42cm8 shell only just missed one of the trains, whose movements were followed by German Drachen balloons. In spite of the trains taking shrapnel fire which fortunately burst too high, the Allied fire was effective, and forced the Germans to pull back.

On 4 October, the trains were fired on by German artillery, and one balloon was shot down by a 4.7in gun, served by Gunner’s Mate T. Potter. On their withdrawal, still under fire, the trains were visited by Winston Churchill, then First Lord of the Admiralty,9 accompanied by Admirals Horace Hood and H F Oliver. On 5 and 6 October, they went into action around Kleine-Miel, supported by two French armoured trains. But on the evening of the 6th, near Buchout, the artillery wagon at the head of one of the trains derailed on a section of line which had been cut by artillery fire. The derailed wagon was detached from the train and left there until the rails could be repaired, which took several hours. In the meantime the remaining five guns of the two trains engaged the German positions and silenced three batteries. On the 7th, the trains were successfully evacuated with reduced crews towards Saint Nicolas, before the lines were cut.

A direct hit on the shield of a 4.7in gun of a Heavy Armoured Train, possibly that on 21 October when Lt Robinson’s train was hit.

(Photo: Le Miroir, 1 November 1914)

One of the 6in guns mounted on a Belgian platform wagon, seen here in Ostend on 9 October 1914.

(Photo: IWM)

A rare postcard, showing the armouring of a wagon of a Heavy Armoured Train. The vertical armour was 15mm thick compared to 10mm for the horizontal plates. Note however the chassis reinforcement system, which is different from that on the other Heavy and Light wagons. This is one of the two British 6in guns.

(Photo: Paul Malmassari Collection)

At Ostend from 12 October the armoured trains covered the withdrawal of troops from Gand. Then on the 15th, one leading and the other as rearguard, they protected the British troops marching on either side of the tracks between Roulers and Ypres. On entering the latter town, the lookouts posted on the engine fired on a scouting party of six German cavalrymen, killing an officer and a trooper. From 19 and 31 October, the trains were made available to General Rawlinson. Armoured Train No 3 (Lieutenant Robinson) went into action in the attack on Menin on the 19th and in the direction of Passchendale on the 20th. On the 21st, the train went into action on the Ypres-Roulers line, where it was fired on by German artillery, which failed to pierce its armour, but which prevented it from advancing further. From the 26th to the 31st, the trains were in action at various locations in support of the Belgian 3rd and 4th Divisions, fighting to the east of Dixmude and to the west of the bend of the Yser.

A photo dated with certainty to 13 November 1914, the square bearing the number ‘23’ is not painted on the train but is a kilometre marker.

(Photo: From J’ai Vu, 13 December 1914)

The 6in guns which had been mounted on bogie platform wagons in Antwerp, were evacuated to Ostende on 7 October, and received their full armour protection in late October. They were formed into a new train which, under the command of Lieutenant-Commander Ridler RN, rejoined the two other trains in the Ypres sector. From 1 to 7 November, the trains went into action against the German lines, and notably against an observation balloon on the 3rd. German prisoners even indicated that the 6in shells from the trains had killed eighty-seven soldiers in a trench on the 6th. Then HMAT Deguise left for Boulogne to be repaired. When it reached Oostkerke on the 11th, it was targeted by two salvoes which fell just 15m short of the train, forcing it to retreat 500m behind the station. But on the 13th, while the train was stationed at Km 23 on the Caeskerke line, a shell hit the second engine, killing the driver. From the 15th, HMAT Jellicoe came under the orders of I Corps, and went into action each day to the east of Ypres. It was also the target of German artillery on the 17th, and one man was wounded. The heavy rail traffic evacuating casualties had prevented the train from quickly manoeuvring out of range. On the 18th, a German shell damaged an engine and one of the 6in guns. The train pulled back towards Ypres Station but the German artillery succeeded in following it and ended up also firing on the station itself. The German bombardment was renewed on the 19th, but the tracks were undamaged.

For its part, HMAT Churchill went into action in December in the area around Oostkerke against German batteries to the south of Dixmude. On 18 December, a shell wounded Commander Littlejohn’s second-in-command. Between the end of December and March 1915, the three armoured trains were continuously in action, sometimes in support of an assault (Jellicoe at la Bassée on 10 January), but in particular in counter-battery or bombardment missions and in actions to neutralise trench lines (Jellicoe at Beuvry between 20 and 24 January, Churchill at Oosterkerke on 28 and 29 January, and against an observation post at Ennetières on 11 February, Déguise at Beuvry firing on a rail junction on the 15th, among other targets, Churchill against a battery at Fleur d’Ecosse on 3rd March). The guns of the trains were extremely effective, notably against troop concentrations: on 18 February, HMAT Deguise fired seven shells at German troops to the South-West of la Bassée. These actions brought the trains within range of the German artillery. The Germans scored hits, but the armour protection and swift manoeuvring of the trains normally protected the crews, except on 25 January when Jellicoe was hit, with two men wounded and the Belgian engine driver killed. Between 10 and 13 March the three trains supported the action at Neuve Chapelle. On that occasion, Field Marshal Sir John French paid a surprise visit to HMAT Churchill, which was the command train for Commander Littlejohns.

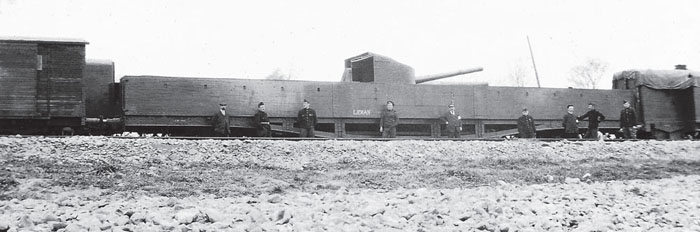

The extreme length (18m/59ft) of the bogie platform wagons used in the trains is evident in this side view of a 6in gun wagon. Note the name ‘Leman’ painted on the side armour.

(Photo: Paul Malmassari Collection)

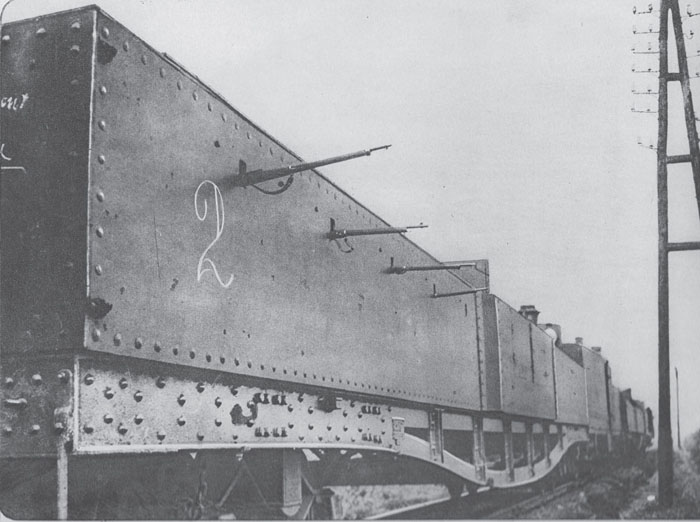

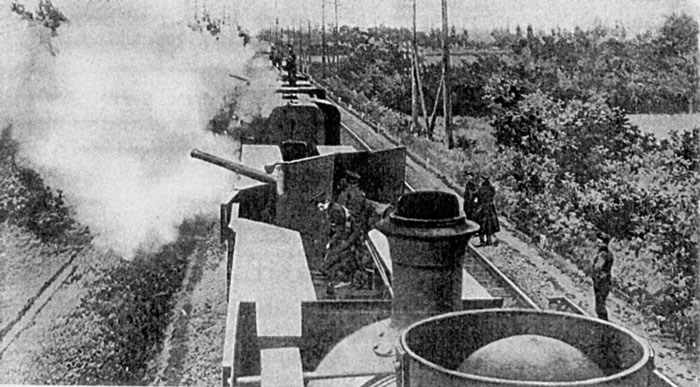

A well-known shot of a Heavy Armoured Train. The length of the protruding rifle barrels adds to the offensive look of the train, even against troops on the ground.

(Photo: Paul Malmassari Collection)

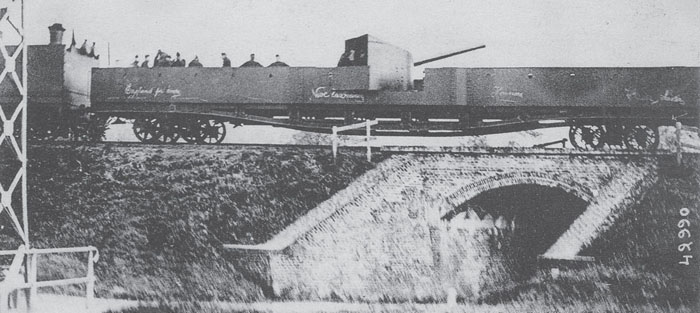

A popular postcard, showing the 6in gun wagon with girder underpinning, where it appears that one of the side doors is missing.

(Postcard: Paul Malmassari Collection)

Another postcard which shows the armoured van between the engine and the gun wagon, beyond which is the second train engine.

(Postcard: Paul Malmassari Collection)

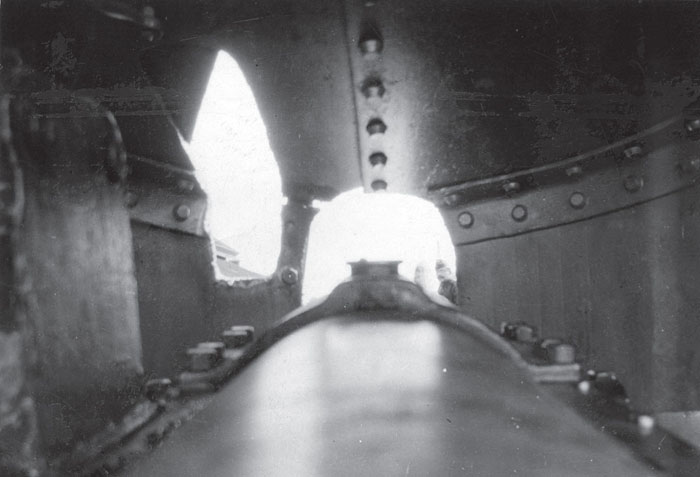

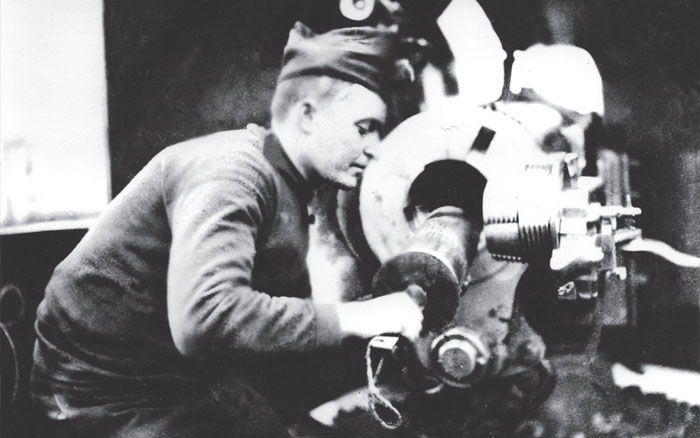

A fine view of the open breech of the 4.7in gun on one of the Heavy Armoured Trains.

(Photo: La Guerre de 1914–1918)

This view, again from La Guerre de 1914-1918, is interesting as it shows the relative lack of comfort for the crews of the gun wagons, even if they are glad of the protection given by the armour!

Here we can see the girders joined in an ‘X’ which support the gun mounting.

(Photo: La Guerre de 1914-1918)

We lack information on the armoured trains after March 1915. Nevertheless, a well-illustrated article was published by the magazine Sur le Front No 18 on 8 May 1915. The photos used in the article show the Light Armoured Trains, which leads us to think that the Heavy Armoured Trains were no longer in use at that time (otherwise they would have been shown), and this was probably because the front lines had become fixed. Finally, the armoured trains were formally taken out of service in September 1915.

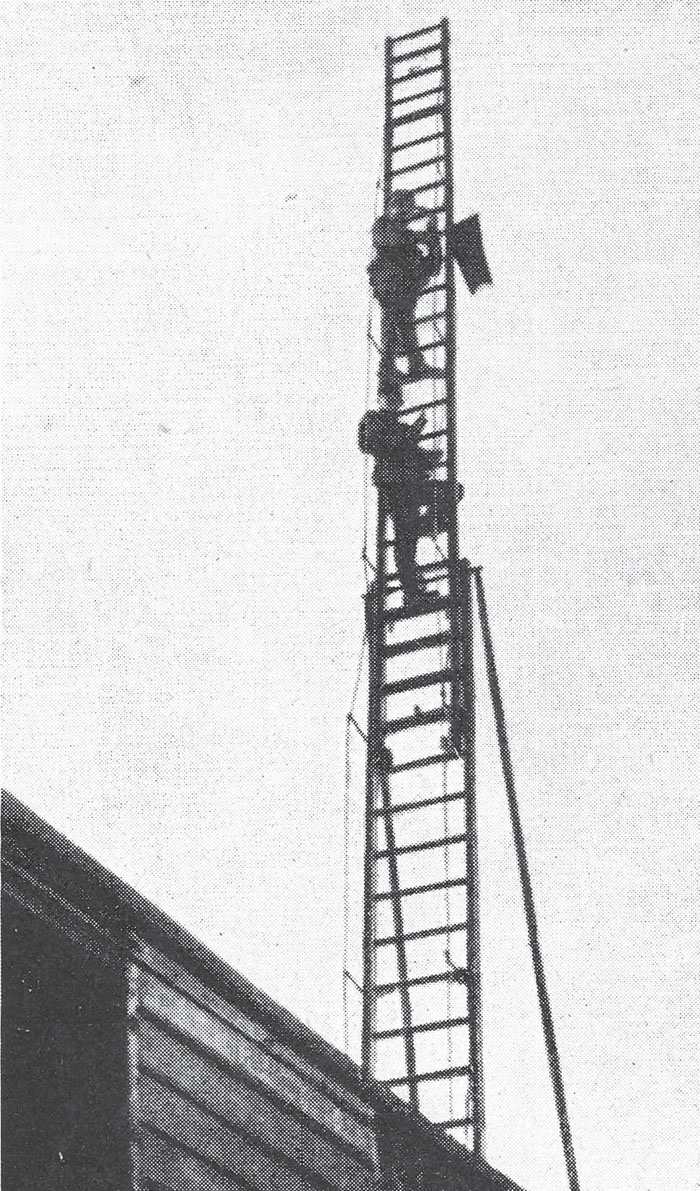

In the section of Commander Littlejohns’ report dealing with the radio sets installed in the trains, he mentions the names of three armoured trains: H.M.A.T. Sinclair, which entered service at Boulogne on 26 December 1914, and which, after the succesful trials conducted up to 7 January 1915, led Commander Littlejohns to introduce H.M.A.T. Singer on 15 January, followed by H.M.A.T. Sueter on 23 January. In addition to their radio sets, they were equipped with a radio mast 8m (26ft 3in) high which could be erected in three minutes, plus 15m (49ft) of aerial cable. This installation gave radio reception over a range of 50km (30 miles) by day and 70km (40 miles) by night. The defence of these trains was provided by a machine gun installed on the roof. We must conclude that the designation ‘HMAT’ was used for convenience in the report but did not correspond with actual armoured trains.

The observation ladder used by the armoured trains in conjunction with observation from balloons and vantage points such as factory chimneys and belfries, which had become priority targets for the gunners of both sides.

(Photo: All Rights Reserved)

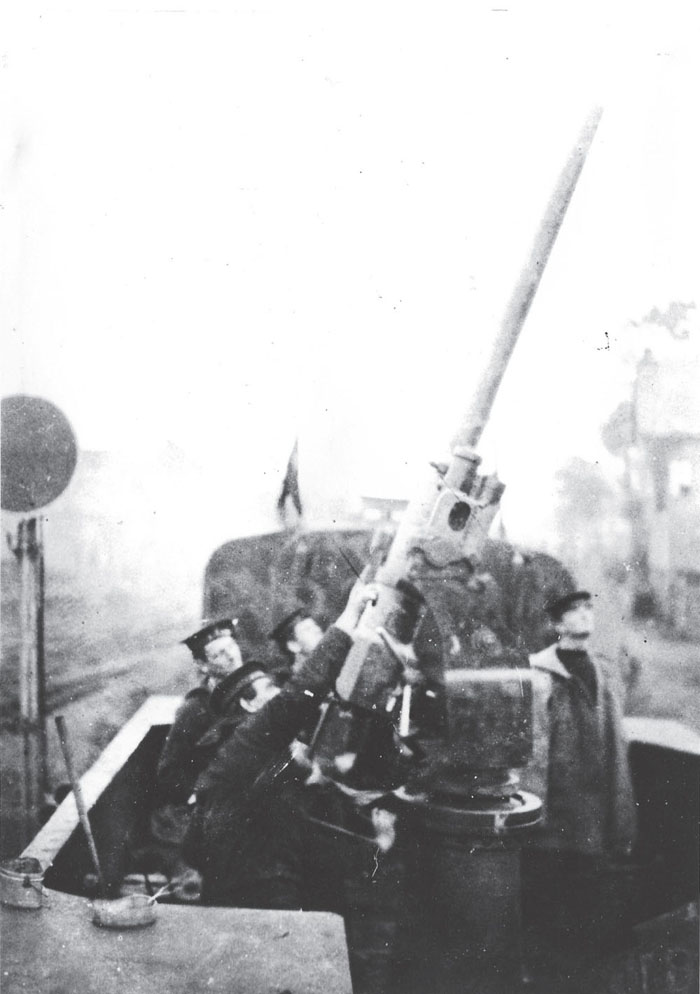

An anti-aircraft gun obviously mounted in the position formerly occupied by a shielded 4.7in gun. There is no documentary evidence to show when this conversion was carried out.

(Photo: All Rights Reserved)

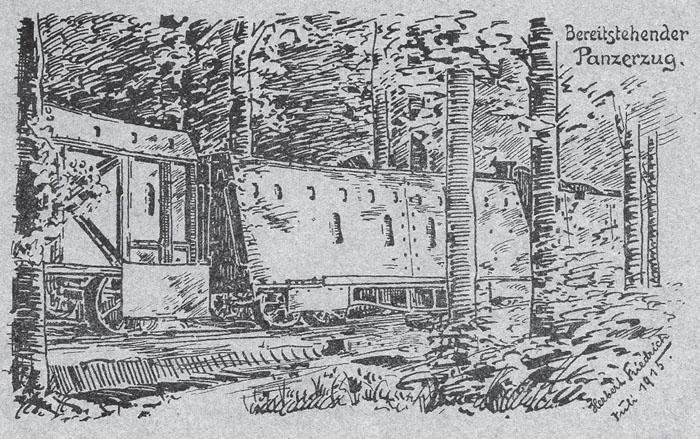

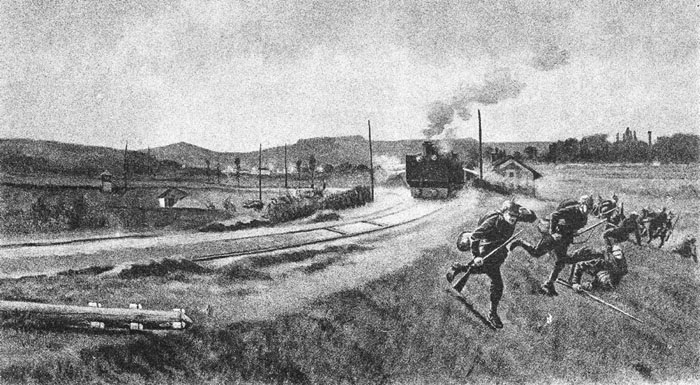

An illustration from a German publication, based on the principle known since the times of Julius Caesar, namely to emphasise the courage of one’s own side by demonstrating the threat or the power of the enemy.

(Illustration: Paul Malmassari Collection)

This postcard seems to have inspired many variations and derivatives, as much by the Belgians and the other Allies as by their enemies.

(Postcard: Paul Malmassari Collection)

Virtually the same view, in an American postcard which places the action at Antwerp.

(Postcard: Paul Malmassari Collection)

This German postcard correctly attributes the train as belonging to the Belgian Army, but sites the scene as being in front of Dixmude; another, this time attributing the train to the German Army, can be seen in the colour section, page 499.

(Postcard: Paul Malmassari Collection)

The engine at the head of a Belgian Armoured Train was not usual. However, certain sources do indicate that each armoured train had one engine which could be used for reconnaissance.

(Postcard: Paul Malmassari Collection)

SOURCES:

Archives:

SHD, carton 9 N 464 SUP

Books:

Littlejohns, Commander A Scott, RN, Royal Naval Air Service: Armoured Trains, Report on Operations Sept. 1914 to March 1915, Air Department, June 1915 (MRA B.1.178.4).

Ministère des Chemins de Fer, Marine, Postes et Télégraphes: Compte-rendu des opérations 04/08/1914 - 04/08/1917.

Scarniet, Vincent, D’Anvers à l’Yser. La Compagnie de Chemin de fer du génie et les trains blindés (Jambes: ASBL Musée du Génie, 2014). Wauwermans Major H., Fortification et travaux du Génie aux armées (Brussels : Merzbach & Falk, 1875).

Journal articles:

Harlepin, J., ‘Les Trains Blindés’, Newsletter of the Centre liégeois d’histoire et d’archéologie militaires Volume IV, No 7 (July– September 1990), pp 45–66.

_________, ‘Les Trains Blindés’, Militaria Belgica (1998), pp 69–88.

‘Trains blindés et “trains fantômes” pendant l’investissement d’Anvers’, Belgian Bulletin of Military Sciences Volume II, No 1 (July 1932), pp 1–14.

Website:

1. Wauermans, Major H, Fortification et travaux du Génie aux armées (Brussels: Merzbach & Falk, 1875).

2. CFG = Compagnie de Chemins de Fer du Génie.

3. On 5 September 1914, the region of Boom and Tisselt; on the 7th, the region of Puurs; the 8th, at Beveren-Waes and Lockeren; the 9th, at Zele and Termonde; from the 11th to the 14th (with Armoured Train No 2), destruction of the bridges at Denderleeuw and Alost on the River Dendre; from the 25th to the 26th, the region of Gand, Grammont, Lessines; the 27th, launching of phantom trains from Muizen towards Louvain; 2 and 3 October, protection of the engineers demolishing the Duffel railway bridge.

4. No 17 MT (0-6-0) of the Compagnie Malines-Terneuzen, and No 3479, a Belgian Class 32 Etat.

5. The equivalent of a Major in the Army (Commandant in French).

6. From 9 November they were allocated the following names: HMAT (His Majesty’s Armoured Train) Deguise (after the Lieutenant-General who was the Military Governor of the Fortress of Antwerp, commanded by the Belgian Captain Servais; HMAT Jellicoe commanded by Lieutenant Lionel Robinson RN, and finally HMAT Churchill, commanded by Lieutenant Ridler RN. The train names were also painted on the wagons. Note that the Belgians serving on these trains wore British uniforms.

7. The first two armoured trains were completed by 25 September.

8. Evidently fired from an M-Gerät ‘Big Bertha’.

9. Churchill was in Antwerp from the afternoon of 3 October to the evening of the 6th.