The very first Chinese armoured trains had appeared at the start of the 1920s during the Zhili-Anhui War.1 Writing in March 1930 an American military attaché described an armoured train he had seen at that time on the Beijing-Hankow line: ordinary flat wagons protected by two thicknesses of mild steel plates. The rapid development of Chinese armoured trains would have to await the arrival of the White Russian mercenaries, notably on the side of the warlord Zhang Zongchang.

In October 1922, the Red Army laid waste to Vladivostok and a large number of White Russian soldiers fled to China with their weapons (it is thought that the famous Zaamurietz/Orlik crossed into China during this period), and took up service as mercenaries in the army of Marshal Zhang Zuolin (Chang Tso-Lin) and one of his subordinates Zhang Zongchang. On 15 September 1922 the latter had been sent to Vladivostok to buy arms. One of his contacts was a certain Nikolai Merkulov,2 who moved to China and became the first commander of the White Russian armoured trains.

The very early White Russian armoured trains were improvised for the most part from bogie wagons reinforced with sandbags. Near the end of the Second Zhili-Fengtian War,3 in October 1924, the forces of Zhang Zongchang (which were part of the Fengtian Army) carried out a surprise attack on the part of the Zhili forces commanded by Dong Zhengguo, and seized the important railway junction of Luangzhou. By blocking the bridge over the Luan River, they surrounded a huge number of men and large amounts equipment. The absorption of these troops increased the size of Zhang Zongchang’s army to 60,000 men in only a few days. The captured railway rolling stock was immediately recovered by Russian engineers, who improvised their first armoured trains (which would be immortalised on film by White Russian cameramen4).

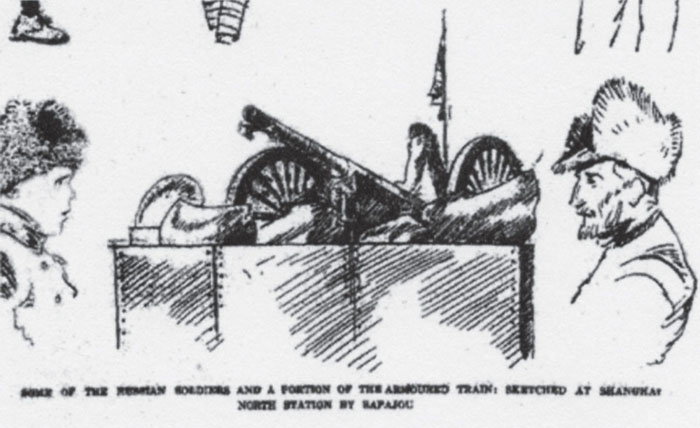

A coup d’état in Beijing had temporarily put Duan Qirui in power. The latter, in order to strengthen the position of his ally Lu Yongxiang in south-east China, and at the same time to crush Qi Xieyuan (the warlord of the Zhili clique), sent Zhang Zongchang to attack towards the south. On 14 November 1924, his troops arrived at Pukou. In the absence of any ferryboat link on the Yangtze between Pukou and Nanjing,5 his soldiers fitted railway tracks aboard barges, and thus ferried their armoured train across the river at night. The resistance they encountered at Jiangsu was weak, and with the armoured train in support the troops of Zhang Zongchang arrived in Shanghai on 28 January 1925. As there were many White Russian émigrés in the town, the Russian soldiers on the train were the subject of a great deal of attention, and it was then that the famous Russian artist Sapajou sketched the armoured train for the North China Daily News.

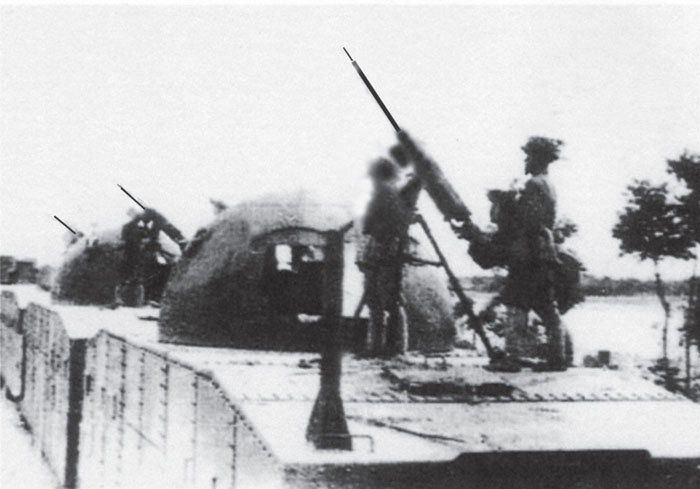

Note the rustic nature of this armoured wagon, obviously reinforced by armour plates and sandbags, and armed with a French 75mm APX field gun.

(Sketch by Sapajou, in North China Daily News, 30 January 1925)

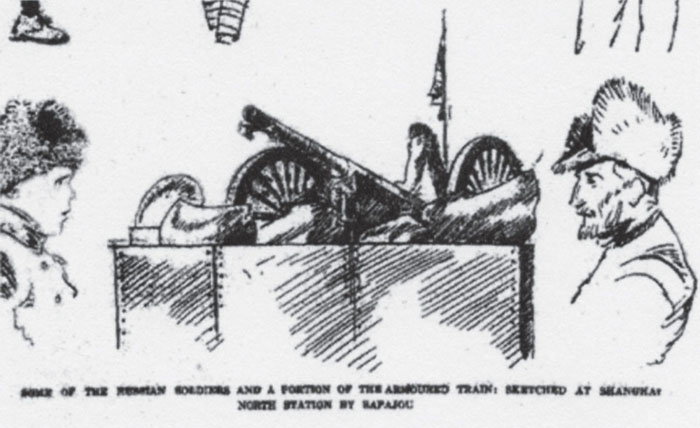

One example of the rolling stock transferred to China at the end of the Russian Civil War: this machine-gun wagon is of White Russian origin. Note the sliding armoured door which was less common than the hinged type.

(Photo: Paul Malmassari Collection)

After Zhang Zongchang had become Tuchun6 of Shandong in early 1925, he discussed with Merkulov the possibility of building classic armoured trains in the Tianjin-Pukou Railway workshops at Jinan, the capital of the Province of Shandong.

One of the most notable actions in which the White Russian armoured trains took part, and in which they suffered badly, occurred during this period. In September 1925 the provisional head of state Duan Qirui decided that two officers of the Fengtian clique, named Yang Yuting and Jiang Dengxuan, should take over as heads of the Provinces of Jiangsu and Anhui. Their appointments infuriated the warlord Sun Chuanfang who was in de facto control of these two provinces, and he immediately sent them away. Zhang Zongchang sent Shi, his highest-ranking officer, to launch a counter-offensive using his White Russian mercenaries, but they were defeated at Bengbu. Shi did not accept this defeat, and with his general staff boarded Armoured Train Chang Jiang (the Yangtse river), and headed for Guzhen to the north of Bengbu to continue the fight. The bloody battle fought there was described as follows by a former regimental commander in the forces of Sun Chuanfang:

After Shi retreated North from Bengbu, he did not admit defeat but continued to command from his armoured train. He was unaware that a regiment of Sun’s forces had marched to the North of the Guzhen railway bridge, thus cutting off his intended escape route, while a second regiment launched a major attack from the South. When he became aware of the southern force, Shi ordered his armoured train to attempt to cut a way through to the North. When he approached the bridge, he saw it was completely blocked by his own troops who were desperately trying to escape to the North. Not wishing to run them down, he decided to change direction and ordered the train to return to the South. He quickly came into contact with the forces of the army of Sun, in overwhelming numbers, and he had to once more reverse course towards the North. Although the railway bridge was still blocked by the throng of his escaping troops, the powerful attacks of his opponents finally convinced Shi that he should ignore the fate of his men and force the crossing of the bridge to save his own skin. Over a thousand men trying to cross were either crushed by the train or thrown into the river. The terrible scene beggared description …

Shell damage to a White Russian armoured train of the army of Zhang Zongchang during the fighting in 1926 between the latter and Feng Yuxiang.

(Photo: Yichuan Chen Collection)

Despite this ruthless action, the armoured train carrying Shi did not escape its fate. Sources differ as to the manner in which the forces of Sun managed to destroy the train, but one suggests that Sun Chuanfang’s artillery played a major role: the White Russian armoured train was hit by shells which caused its ammunition to explode. Most of the White Russians fought to the death, but others chose to surrender along with Shi himself. Very few of the mercenaries escaped. To show his fury at the way the fighting had developed, Sun Chuanfang immediately ordered that Shi be beheaded, and all the prisoners executed. One officer of his army who inspected the battlefield wrote that: ‘The wreck of the armoured train of Zhang Zongchang was lying on its side, blocking the track. The White Russian soldiers, apart from a few who had escaped, had been burnt alive inside the armoured train. Their remains resembled piles of coal, and they were completely unrecognisable.’

In early 1926, a number of completely redesigned armoured trains were built at Jinan. According to a Chinese source these trains (the Tai Shan, the Shan Dong, the Yun Gui and the He Nan7) were converted from 40-tonne bogie flat wagons, passenger coaches and steam engines, armoured with steel plates 20mm thick. Following the lesson of the Battle of Guzhen, all these trains included flat wagons carrying searchlights and materials for track repairs.

The armoured trains8 were composed of eight wagons:

7.7cm FK 96 (German) or 75mm Type 38 (its Japanese version), crewed by White Russians.

(Photo: Philip Jowett Collection)

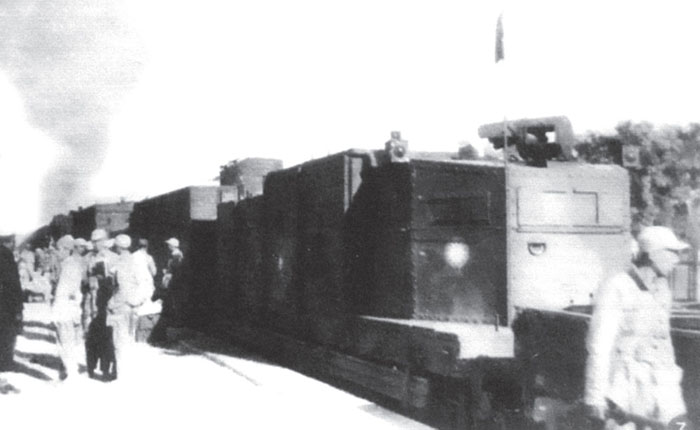

Note the mixed Russian and Chinese crew of this armoured train.

(Photo: Paul Malmassari Collection)

It was possible to pass between wagons (2) to (7) via armoured gangways. Finally, a wagon carrying two sections of Chinese infantry for close-in protection brought up the rear of the train.

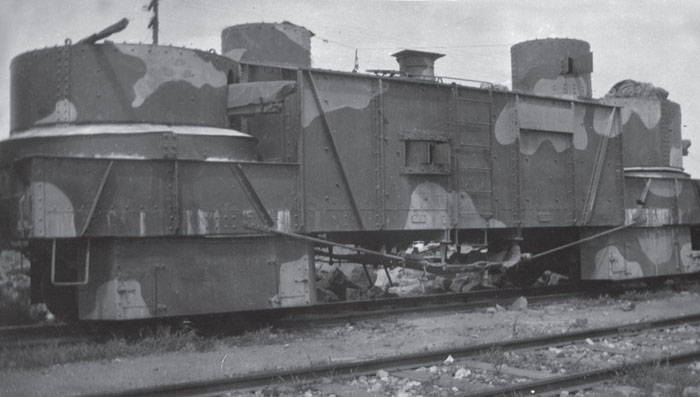

In theory, their armament was to consist of seven 75mm Japanese Type 38 field guns and twenty-four Maxim heavy machine guns, but evidence from photographs shows that in fact there were major divergences from this. The floors of the artillery wagons of Tai Shan were protected by a layer of reinforced concrete poured onto a steel plate fastened to the metal floor of the wagon. Also the vertical side walls were formed from two metal plates with the intervening space filled with concrete. To carry the increased weight, additional springs had to be fitted to the bogies. These trains were finished in a three-colour camouflage scheme. Two other armoured trains were also built in the workshops of the Beijing-Hankow Railway at Chang Xin Dian, to an identical design to the trains of the Province of Shandong, by order of Chu Yupu, the main ally of Zhang Zongchang and Governor of the Province of Chili during this period.

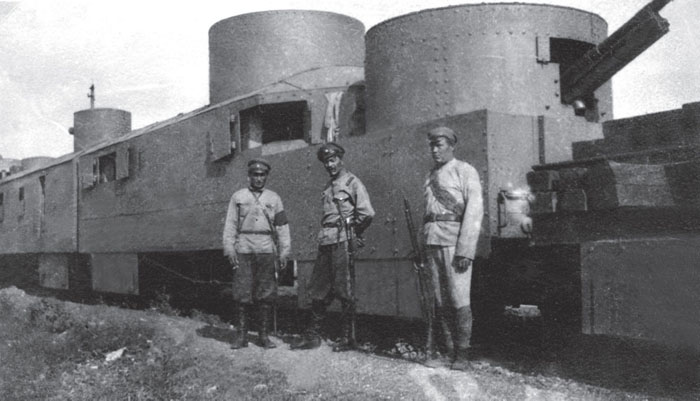

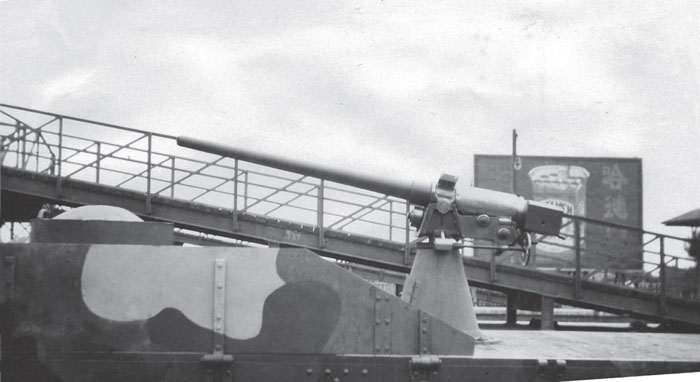

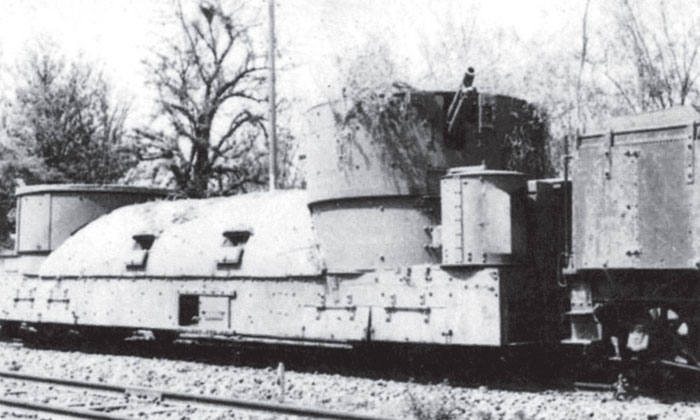

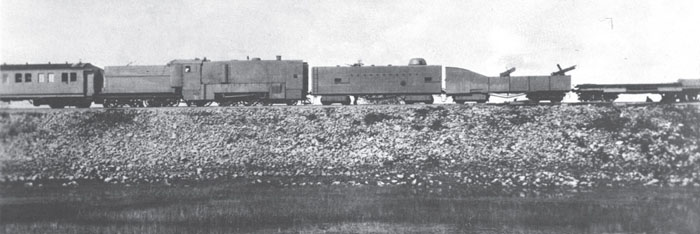

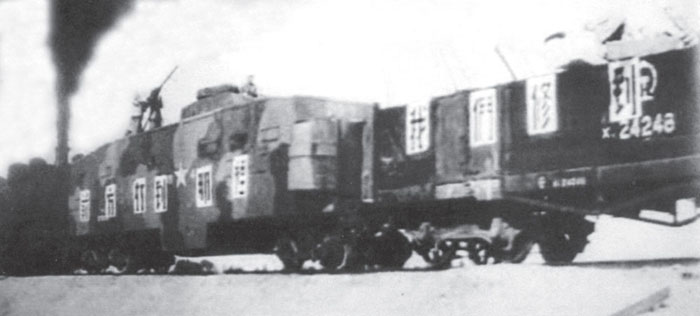

The safety wagon carrying a hand trolley, at the head of a White Russian armoured train, captured at Chin Wang Tao, seen here in 1928.

(Photo: Paul Malmassari Collection)

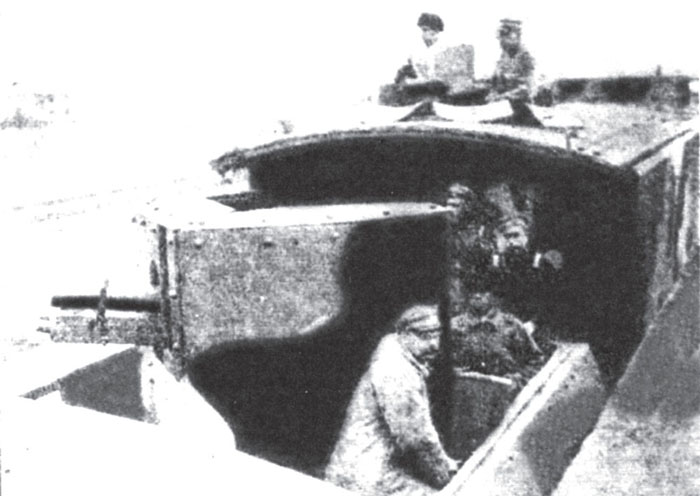

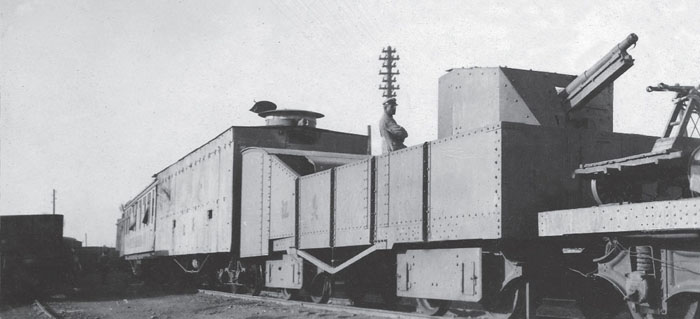

One of the artillery wagons from the same train. The turrets here are both armed with Russian 76.2mm Putilov guns. On the original photo it is just possible to make out the former Russian roundel in the centre of the side armour, under the new coat of camouflage paint.

(Photo: Paul Malmassari Collection)

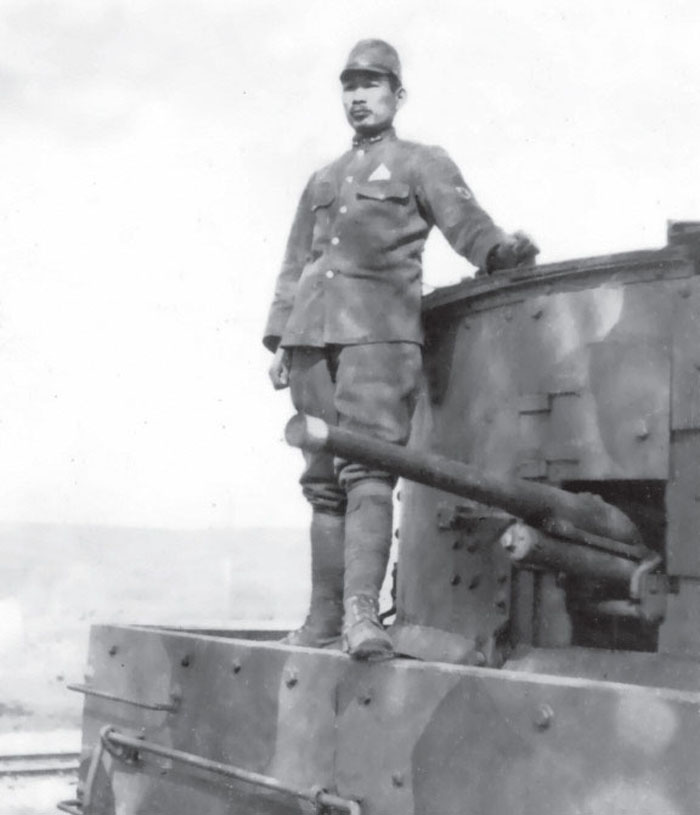

The next wagon in line is perhaps the command wagon, coupled directly in front of the engine.

(Photo: Paul Malmassari Collection)

The train’s engine, on which the simple form of the armour is intended to enable it to blend in with the wagons.

(Photo: Philip Jowett Collection)

This artillery wagon has two different turrets, both apparently armed with 75mm Type 38s.

(Photo: Paul Malmassari Collection)

In early 1927, a White Russian armoured train, the Chihli, was placed in service at Tienstin by the forces of the Fengtian.9 Composed of six wagons arranged symmetrically on either side of the engine, it was armed with 75mm guns (in the lower turrets of artillery wagons Nos 2 and 6, with a horizontal field of fire of 270 degrees) and 47mm guns (in the upper turrets, with a 360-degree field of fire). Wagon No 3 carried a Stokes mortar in a circular tub mounted centrally on the wagon. According to certain other contemporary sources, it carried a different armament: as with other White Russian trains it carried eight to twelve heavy machine guns, and the artillery was 76.2mm Putilov models with between 200 and 300 shells per gun. As for the engine, its armour was designed to give it a similar outline to the machine-gun wagons.

Wu Peifu and Zhang Zuolin were the two most important warlords who used armoured trains other than those of the White Russians. Their crews were primarily Chinese. Wu Peifu began to use armoured trains in the mid-1920s, after he had rebuilt his forces following the defeat he had suffered during the Second Zhili-Fengtian War in 1924. They were probably inspired by the White trains of Zhang Zonchang and of Chu Yupu, but it appears, however, that their technical characteristics and operational doctrines were inferior to those of the Whites. The only information we have is that they were built at Hankow by the Mechanical Workshops of the Yang Tze, specialists in ship construction, including the gunboats of the Chinese Navy. The financial investment in the trains was so heavy that it brought about the bankruptcy of the Workshops in 1926.

In 1925, the principal adversary of Wu Peifu was the Kuominchun,10 whose Second Army commanded by Yue Weijun occupied Xinyang in the Province of Henan. Kou Yingjie, one of Wu Peifu’s commanders, had used armoured trains during the siege of that town in the Winter of 1925. According to the memoirs of an officer, Kou had planned to embark a large number of shock troops in an armoured train. The train was to have been used as a battering ram, supporting the main assault on the city by disem-barking its troops to overwhelm the defences constructed along the line of the railway. Despite the advice of one of his subordinates that the enemy’s dispositions could be intended as a trap for any such action, the order was given to attack. Barely had it begun to penetrate the enemy lines, when the train plunged into a large ditch prepared by the defenders. Although the sides of the train were armoured with iron plates, the wooden roof offered scant protection, and the troops inside were wiped out by the enemy firing from the high ground on either side of the ditch.

Paradoxically, the first battle between armoured trains did not involve the modern trains such as those of the White Russians, but rather the trains of Wu Peifu and Zhang Zuolin. Very little information survives on the trains of the latter. According to the memoirs of Marshall Zhang Xueliang, these improvised trains were built on the Central East Railway by the troops of Zhang Zongchang, when his army was in Manchuria in the early 1920s. Sleepers and lengths of rail had been used as armour by pouring cement between them, and their armament consisted of artillery and machine guns. The crews were Chinese.

Although Wu Peifu allied himself with Zhang Zuolin and the letter’s subordinates Zhang Zongchang and Chu Yupu in their common struggle against the forces of the Kuominchun, the year 1926 had seen the rout of Wu Peifu’s main forces faced with the rapid advance of the Nationalist ‘Expedition of the North’.11

It was now, with Wu at a disadvantage, that once again Zhang Zuolin looked on the troops of Wu as standing in the way of his ambitious plan to conquer the whole of China. He therefore declared war in February 1927, sending his elite troops into Henan Province to attack those of Jin Yun-é who was loyal to Wu.12 This would be the last great battle between the ‘historic’ Warlords of the North. For his part, Jin Yun-é launched his own counter-offensive against the city of Zhengzhou, led by his most loyal commander, Gao Rutong. At least one armoured train was used by his main force along the Beijing-Hankow railway line, guarded on each flank by the infantry. The official report of the Fengtian Army, preserved in the archives, describes the battle as follows:

On the morning of 24th March, the enemy commander Gao Rutong, accompanied by his bodyguard and his shock troops, took personal control of an armoured train, and led a major attack. After advancing towards Wu-shi-li Pu along the Beijing-Hankow railway, the enemy was surrounded and their armoured train destroyed by our artillery. Gao and his head of staff Shen Qichang, his brigade commander Song Jiaxian and 40 other officers were killed inside the armoured train. The enemy forces thereafter retreated towards Xinzheng. After the battle, over 1,000 men were taken prisoner, and their armament, including one armoured train, eight artillery pieces and a large quantity of small arms, were captured. The bodies of General Gao and the other officers were sent to Zhengzhou and buried with all due honours.

A fascinating view of an armoured train built of cardboard on 1 September 1926, in honour of the dead of the Fengtian and Chili-Shantung Armies during the war against the Kuominchun. Interestingly, modern-day Chinese still leave presents such as televisions and microwaves made of card and paper as symbolic offerings on the graves of their ancestors.

(Photo: Yichuan Chen Collection)

The above official report does not mention the role played by the Fengtian armoured train. But several descriptions prove that it was involved in a rather curious train-versus-train combat. In the 1960s, Xu Xiangchen, a close subordinate of Jin, wrote on the subject of this battle:

A major obstacle to the advance of the troops of Jin was a Fengtian armoured train positioned to the South of Zhengzhou. Goa had planned to use the coupling hook of his own armoured train to harpoon that of the Fengtian Army’s train in order to capture it. Gao’s train was able to make its approach to the Fengtian train and managed to couple to it. However, he possessed only one engine as against the enemy’s two (although individually of less power). After stalling for a moment, the coupling on the engine of Gao’s armoured train let go, and the whole of his train was pulled towards the Fengtian lines, with Gao still on board. The latter ordered his on-board artillery to fire on the enemy train. The gunners on the Fengtian train replied, and the whole of Gao’s train was destroyed, Gao being killed during the fight.

Marshal Zhang Xueliang, fighting on the other side, recounted this episode in his memoirs:

Cao Yaozhang, commander of the squadron of armoured trains, gave me the following report of the fighting. When in action our armoured train was always accompanied by the infantry, and in fact two companies of infantry had supported the train on the previous day. Following hard fighting, the infantry retreated, abandoning the train which had no engine attached. The troops on the train reported this to their commanding officer, who told them not to panic as he believed the engine would return to find them the next morning. In the morning, the train in fact began to roll, but the crew quickly noticed that they were going in the wrong direction. After checking on the situation, they concluded they were being towed by an enemy train – the mobile command post of Gao Rutong. At one end of our train was a Russian cannon, originally installed by the men under Zhang Zongchang. A section head in charge of the cannon fired desperately on the enemy train. The shock effect on the closed-up wagons killed many of the soldiers in the enemy train.

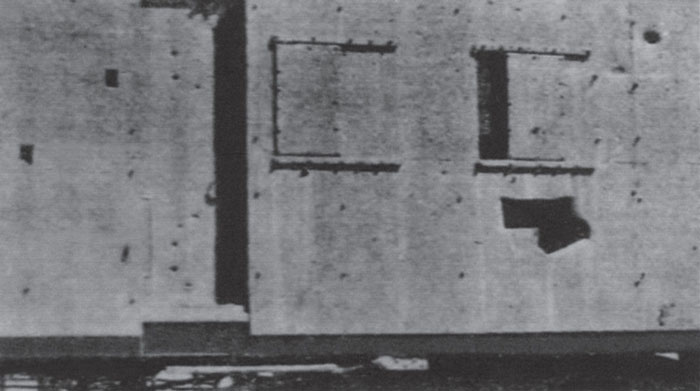

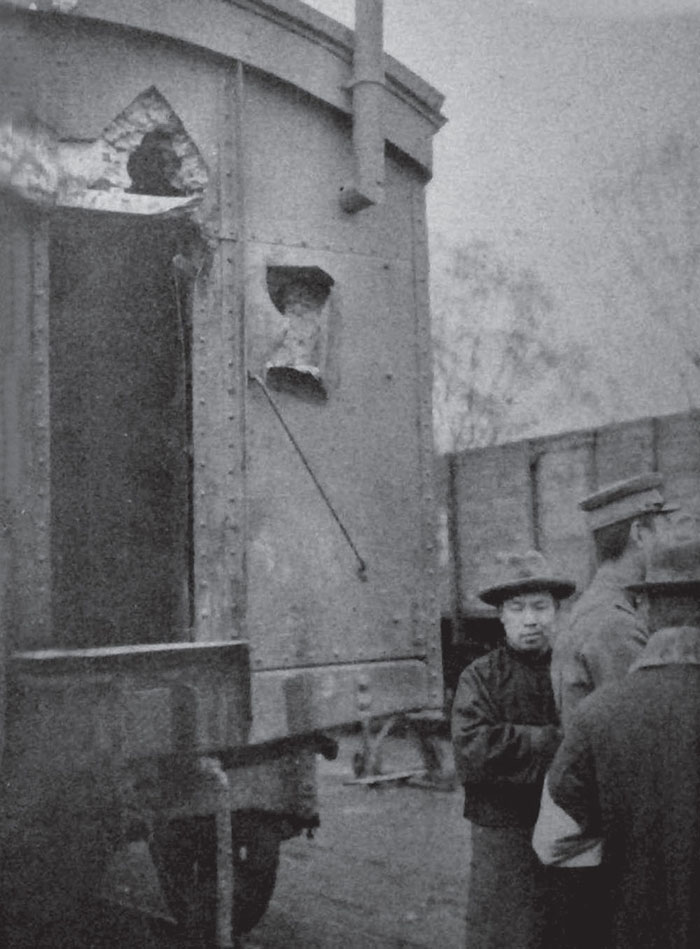

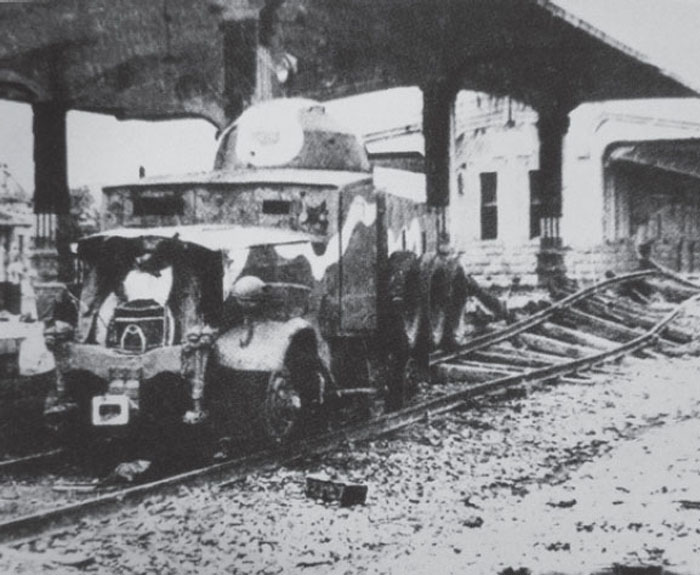

This remarkable photo of Gao Rutong’s armoured train allows us a view of the cement backing to the vertical steel armour plating. One or more shells have evidently penetrated and exploded inside, with devastating effect.

(Photo: History Illustrated, [June 1927], Yichuan Chen Collection)

Although the reports differ in the details, the accounts from both sides agree on the main features of the incident. A photo of Gao Rutong’s wagon damaged by artillery fire appeared in various Chinese and Japanese publications.

The first armoured trains of the Nationalist Government in Canton, including the famous ‘armoured train squadron of the Grand Marshal’ (in other words, Sun Yat-sen, who was proclaimed Grand Marshal of the Army and the Navy by the government run by the Communists), were all of improvised construction. A Soviet adviser14 described one of the trains on which he had travelled in 1925: ‘The equipment of these trains was very rudimentary, consisting of goods wagons armoured with iron plates, and they even lack flat wagons.’ Perhaps these were trains put in service to counter the bandits who had roamed around Canton since the beginning of the twentieth century. They remained extremely active, and the railway was their target of choice. In 1925 the managers of the Canton Railway had sent four recommendations to the Nationalist Government for the protection of the railway, and the first one concerned the establishment of armoured trains to protect the passenger trains.

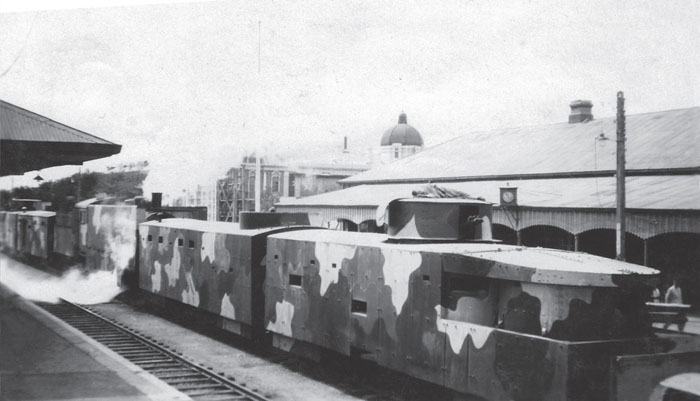

An armoured train photographed between 20 and 27 February 1927 in Beijing by a British married couple. Note the artillery wagons inserted between the armoured machine-gun wagons.

(Photo: Paul Malmassari Collection)

The commanders of the National Revolutionary Army responded rapidly, and by 1926 the protection of all the commercial trains on the main lines around Canton was assured by armoured wagons. According to the newspapers of the period, these ‘armoured trains’ comprised a single armoured wagon, manned by soldiers, and hauled by a small steam engine.

One armoured train, probably of the same improvised type (with protection consisting of sleepers and sandbags) was put into service by the volunteer workers of the Canton-Hankow Railway during the difficult siege of the town of Wuchang, controlled by the forces of Wu Peifu, by the Fourth Army of the National Revolutionary Army (ANR). In order to defeat the ramparts, the sappers carried out a mining operation under the protection of the armoured train. But during an enemy sortie, the forces of Wu Peifu surrounded and temporarily captured the armoured train. After the town fell, General Chiang Kai-shek ordered the Hanyang Arsenal to build armoured trains after consulting with Soviet advisers.15

The armoured trains of the ANC employed during the attack on Shanghai were still of the improvised type. In his memoires, General Bai-Chongxi tells that an armoured train armed with Russian 76.2mm guns had been used at Songjiang near Shanghai, to cover the assault sappers tasked with clearing the barbed wire entanglements which were blocking a railway bridge, and at the same time to destroy enemy machine-gun nests.

According to the photographic record, the improvised trains of the ANR were simply reinforced vans, with loopholes for firing rifles and machine guns cut in the side walls. 82mm trench mortars were mounted on revolving platforms protected by iron plates, probably inspired by the heavy 150mm mortars on the White Russian armoured trains.

After the fall of Shanghai, several White Russian armoured trains were captured by the ANR. According to the memoires of Zhang Pei, a staff officer of the ANR, hundreds of White Russian soldiers were captured at Songjiang along with their armoured trains, on which ‘the wagons used by the officers were richly decorated, and contained expensive cigarettes and perfumes’. A Soviet adviser demanded that all the White Russians be decapitated, which was then carried out.

The captured White Russian armoured trains were all reused by the ANR against their former owners and were often renamed Zhong Shan in honour of Sun Yat-sen,17 differing only by a following number. One source indicates that during the Expedition of the North, twenty armoured trains bearing this name were created from captured wagons.

One of the very early improvised Nationalist armoured trains, photographed at Canton.

(Photo: Yichuan Chen Collection)

Seen near Shanghai in 1927, this tub shelters a 150mm mortar served by the White Russian crew of the Chang Chen (‘Great Wall’).

(Photo: Paul Malmassari Collection)

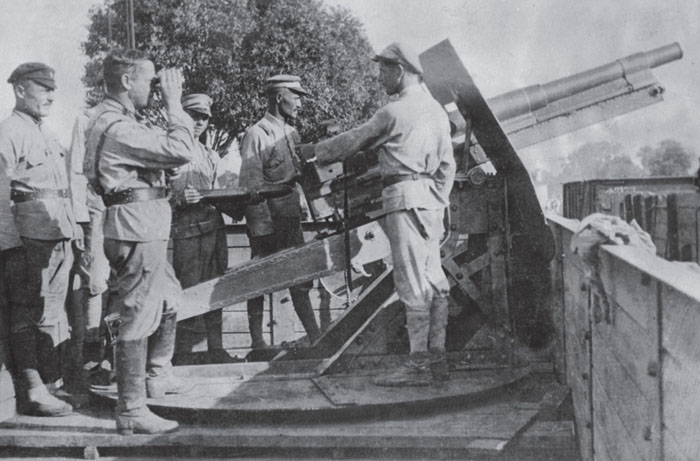

Chang Chen seen at Shanghai in April 1927, preparing to repulse the attack by Communist troops. The gun is a 7.5cm/L14G ‘Shanghai-Krupp’ mountain gun.

(Photo: Yichuan Chen Collection)

One of the 82mm mortars on the Zhong Shan No 1 photographed in July 1927.

(Photo: Yichuan Chen Collection)

The Nationalist armoured train Zhong Shan, photographed in August 1927 after being captured from the Northern forces.

(Photo: Paul Malmassari Collection)

After having captured the cities of Shanghai and Nanking in April 1927, the Nationalist Government of Chiang Kai-shek broke with the rival Government of Wuhan and began eliminating the Communists. At the same time the Nationalist forces continued their progression against the forces of Zhang Zongchan and the other Warlords, in what was known as the ‘Continuation of the Expedition of the North’.

Their primary objectives were the minor towns around Nanking to the north of the Yangtze. The Northern forces had placed their best units, including the 65th Division consisting of White Russian soldiers and armoured trains, near the railway junctions of Hua Qi Ying and Dong Ge.18 Despite their dispositions, they found themselves unable to check the advance of the numerically superior Nationalist forces, who continued to advance northwards. The two sides clashed again in the town of Linhuai,19 where according to reports, an armoured train named Hubei was captured.

These actions formed only a minor part of the great advance across the northern province of Jiangsu and the Province of Anhui to the north-east. Although the Northern forces were superior technically, employing armoured trains, White Russian cavalry units and aircraft in their defensive actions, the town of Xuzhou finally fell on 2 July 1927. According to the report by General Bai Chongxi, three Northern armoured trains were destroyed in the course of the fighting. The Nationalists were finally stopped when they entered Shandong, when the troops of General Wang Tianpei found themselves held up to the south of the Grand Canal.20 The latter wrote in his memoirs that ‘the enemy was bolstered by his barbaric armoured trains and bombarded us night and day, our efforts to cross the Canal being countered at every turn by overwhelming firepower’.

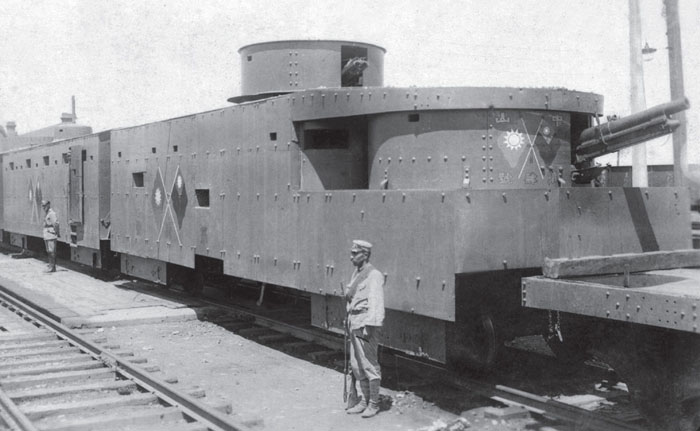

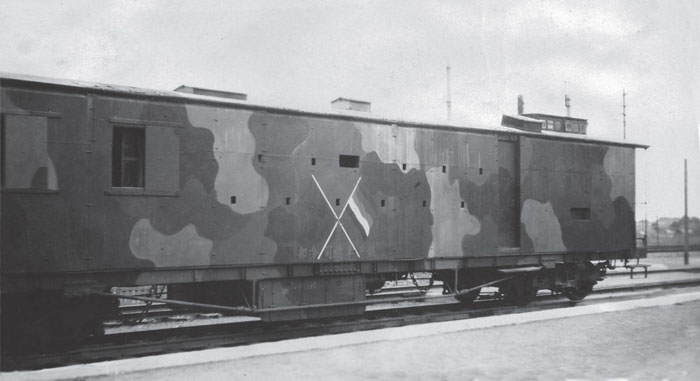

An overall view of Hubei (from the name of the Province, Hopei) captured by the Southern Army, seen here at Tientsin in 1927.

(Photo: Paul Malmassari Collection)

Chiang Kai-shek and Feng Yuxiang (known as ‘the Christian General’) concluded an alliance at Xuzhou. However, the rear of the forces of the Nanking Government were threatened by their opponents in the Government of Wuhan, which also possessed powerful armies. Accordingly, Xuzhou was abandoned on 7 August and the Nationalist troops rapidly withdrew to Nanking. Seizing their opportunity, the Northern troops returned from Jinan, supported by armoured trains, and very soon after reached Pukou, leaving the Yangtze River as the only obstacle before the capital of the Nanking Government. It appeared that at this moment the course of history was about to change.

According to contemporary reports, the armoured trains in Pukou Station were used by the joint forces of Sun Chuanfang and Zhang Zongchang as mobile artillery batteries, supporting the amphibious attack attempted against Nanking. But the guns of the trains could not neutralise the heavy naval guns positioned along the bank of the Yangtze to the north of the city. The coastal batteries repulsed not only the armoured trains, destroying one of their steam engines, but also the infantry attempting a landing. Finally the forces of Sun Chuanfang crossed the river and landed beside the town Longtan, out of range of the coastal defence batteries. But just as Nanking seemed on the point of falling, the Nationalist forces launched a desperate counter-attack, encircling the forces of Sun Chuanfang. Nanking had been saved.

The command wagon of Hubei bearing the inscription ‘Armoured Trains General Staff ’ on its side.

(Photo: Paul Malmassari Collection)

An anti-aircraft gun on the forward flat wagon of Hubei, devoid of armour protection apart from the low side plates here seen in the raised position.

(Photo: Paul Malmassari Collection)

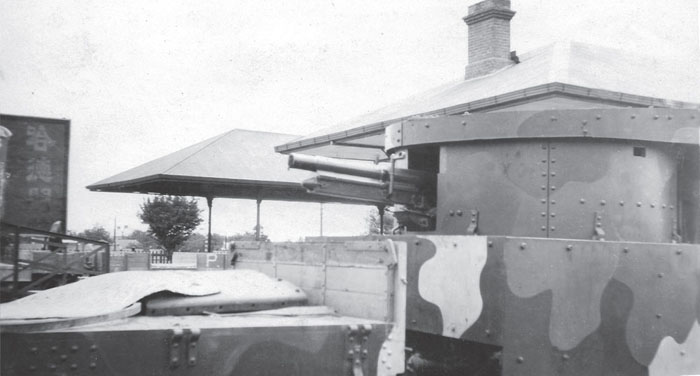

Close-up of one of the artillery wagons of Hubei, armed with a 75mm Model 38.

(Photo: Paul Malmassari Collection)

Needless to say, the fighting continued, bloodier than ever. The most serious combat involving the White Russian armoured trains took place in Linhuai and Fengyang. These two towns fell to the Nationalists on 11 and 12 November 1927 respectively, but the crucial strategic site of Ma An Shan21 changed hands several times. It was finally held by the Northern forces, and blocked the Nationalists’ advance towards Bengbu. Four troop trains protected by two armoured trains had been sent to reinforce the Northern forces.

A Nationalist trolley converted locally from a Japanese road-rail truck, captured in Jinan Station in August 1927. Note the road wheels on the hull and the searchlight on top of the dome-shaped turret.

(Photo: Yichuan Chen Collection)

The armoured trains terrified the Nationalist soldiers: Nationalist General Xu Tingyao even declared that the White Russian crews were cannibals who killed captured soldiers in order to eat them. On their own side, the Nationalists had no artillery capable of inflicting any serious damage to the armoured trains. The General wrote:

On the third day we were at Linhuai, the number of enemy armoured trains increased to four. The White Russian crews, after having drunk wine,22 fired on us furiously and when our offensive had been stopped, they arrived to repair the tracks and advanced. Two of the armoured trains advanced up to 4 km behind our lines and fired on us from behind. On the fourth day, seven enemy divisions completely surrounded us, and the situation was only improved on the fifth day thanks to the arrival of nine of our divisions.

On 16 November 1927, the Nationalists broke through into Bengbu, while the White Russian armoured trains continued to support the Northern troops during the street fighting. All combat finally ended at 16.00 on the same day.

The Nationalists’ next objective was Xuzhou. Although no descriptions of the actions involving the White Russian armoured trains have come to light, several Nationalist reports, and various publications, referred to the power of the enemy trains in their accounts of the fighting during the second battle for Xuzhou. The armoured trains, together with the air element and the trench mortars, were the three most formidable arms deployed by the Northern troops. But this time, the battle lasted only four days and ended with the Nationalists seizing Xuzhou, in the process capturing at least one armoured train.

The war rapidly spread in the south of the Province of Shandong and as usual, the Northerners made effective use of their armoured trains. According to Nationalist documents, two tanks and four armoured trains were used by the forces of Zhang Zongchang. However, at this point we should pause to consider the use of artillery and armoured trains by the Nationalists. On the night of 17/18 April 1928, the Nationalist armoured train Shandong (perhaps an ex-White Russian armoured train, from its name) and artillerymen with six Krupp guns (also captured from the Northerners) were ordered to advance to protect the line near Tengxian (today a city in south Shandong), and to destroy enemy armoured trains. However, they arrived too late to engage the latter, as the following report describes:

During the attack on Tengxian on 17th April, the Engineer Corps of the 9th Army had destroyed a length of track to the south of Tengxian, and had succeeded in surrounding an enemy armoured train. At this juncture, our artillery had not arrived, and our armoured train could not advance due to the damaged track. If our artillery had arrived in time, or if the track had been repaired more quickly, we would certainly have captured the enemy armoured train.

In the days which followed, the Nationalist armoured trains were primarily used for counter-battery fire, particularly against the enemy armoured trains. In the battle around Tai’an, two Nationalist armoured trains, Zhong Shan No 4 and Ping Deng (‘Equality’), engaged three White Russian armoured trains. At the same time, armoured trains were employed by the Kuominchun under Feng Yuxiang in their fight against the Northern Warlords, as the former advanced across the province of Hebei towards Tianjin (Tientsin) and Beijing.

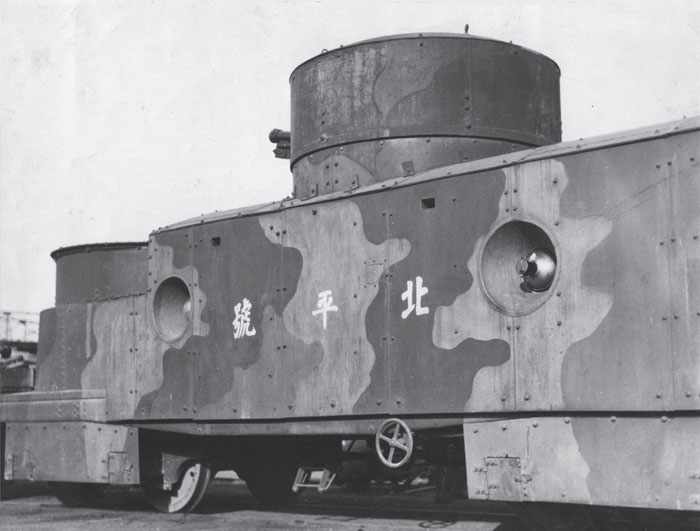

Armoured Train Beijing.

(Photo: Philip Jowett Collection)

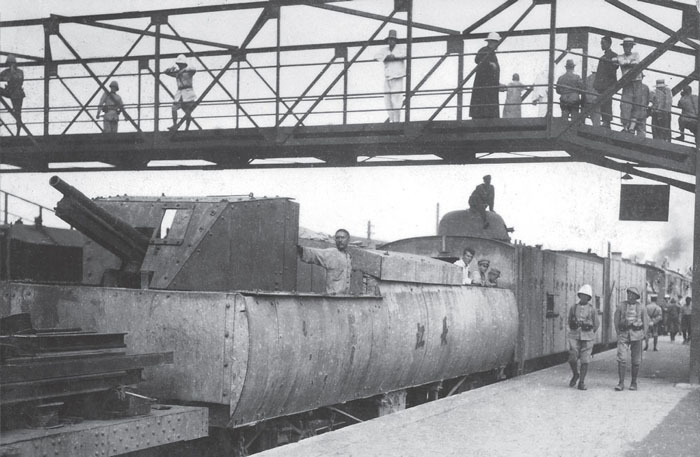

An artillery wagon of Armoured Train Chang Jiang (‘Yangtse River’) at Tianjin (Tientsin) in around 1928. Note the two French soldiers, probably from the Corps d’occupation de Chine (COC = China Occupation Force) which in 1929 became the Troupes françaises en Chine (French Troops in China).

(Photo: Paul Malmassari Collection)

Another artillery wagon of the Chang Jiang, with the hull armour extended upwards probably to offer increased protection to the gunners serving the gun in its open-backed shield.

(Photo: Paul Malmassari Collection)

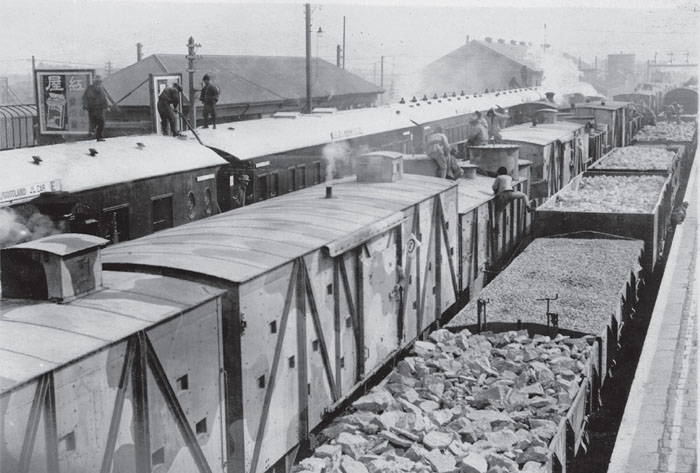

Armoured train at Mukden (the modern Shenyang) in 1928. The second wagon in line has an armoured tub on the roof, perhaps for a mortar. The flat wagon in the foreground is loaded with sleepers.

(Photo: Paul Malmassari Collection)

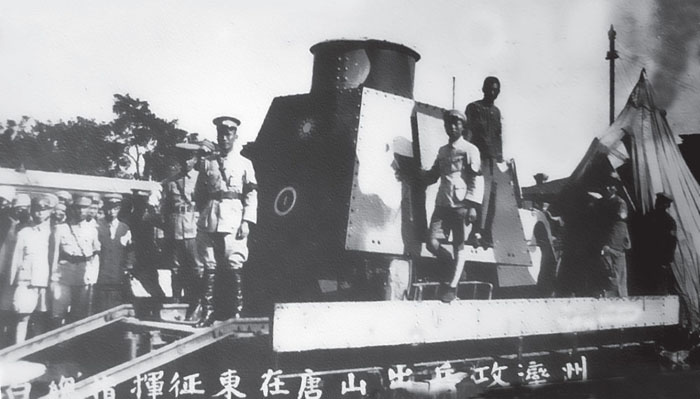

Nationalist armoured trolley employed in September 1928 at Tang Shang. Standing front left is General Bai, whose son wrote a book containing his father’s memoirs.

(Photo: All Rights Reserved)

Tientsin and Beijing fell to the Nationalist forces in June. On 4 July 1928, Marshal Zhang Zuolin who was the major supporter of the Northern forces (by this time consisting principally of the troops of Zhang Zongchang and Chu Yupu) was assassinated by the Japanese. Almost immediately, Zhang Zongchang and Chu Yupu fell out with the ‘Young Marshal’ Zhang Xueliang, who allied himself with the Nationalists and ordered the Northern warlords to cross the River Luan to reorganise their forces as part of the Fengtian Army. Zhang Zongchang made his last address to his troops, who still numbered some 70,000 men, in his brutal bandit chief style, asking them to attack their former allies, the Fengtian Army. The attack by Nationalist forces supported by the armoured trains Honan and Min Sheng put a stop to his plans.

According to a Nationalist report, the Northern forces still possessed at least three armoured trains. Heavy fighting took place between Nationalist and Northern armoured trains. On 12 August 1928, the remaining Northern forces crossed the River Luan, only to be defeated by a combination of the Northern Warlords and the Fengtian Armies. Surviving documents of the latter indicate that the three remaining armoured trains of the Northern troops, with their White Russian crews, changed sides and joined the Fengtian Army, in passing wiping out the last Northern troops who had not surrendered. Thus a page of history was closed, the adventure of the armoured trains of Zhang Zongchang coming to an end there where it had begun four years earlier.

An obscure chapter in the history of the Chinese armoured trains was written in Northern China between 1925 and 1928. It involved the struggle between the White Russian armoured trains of Zhang Zongchang and their lesser-known adversaries, the Soviet-designed armoured trains of the Kuominchun under General Feng Yuxiang. According to Russian sources, five armoured trains designed by Soviet advisers working with the Kuominchun were built in the Kalgan workshops (the modern Chang-chia-k’ou) in May 1925. The existence of the trains and the advisers is confirmed in the journal of General Feng Yuxiang, but information on and photos of these trains and their operations are extremely rare.

Like the Nationalists in the south, in 1927 and 1928 the forces of the Kuominchun made rapid advances against the Northern warlords, and several White Russian armoured trains were captured. With these trains and others built locally, the Kuominchun rapidly consolidated an armoured train force which equalled the Nationalist trains of Chiang Kai-shek. In May 1929, Fen Yuxiang formally declared war on Chiang, and in March 1930 Yan Xishan from Shanxi allied himself with Feng. China was once more plunged into civil war.

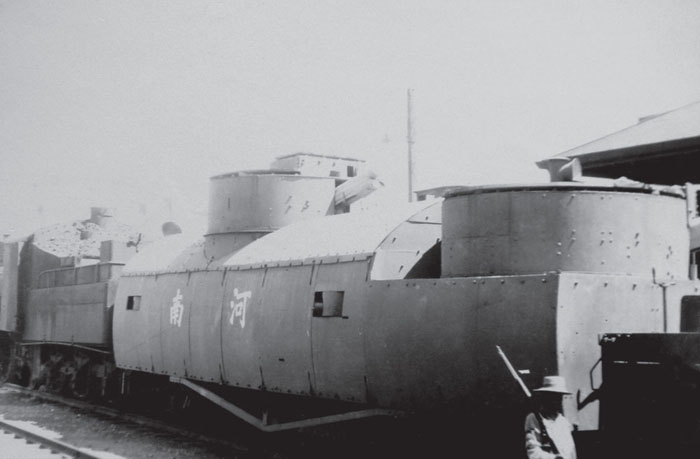

A rear wagon of the Ho Nan, with the now classic layout of two artillery turrets.

(Photo: Philip Jowett Collection)

Chinese crew members of the Ho Nan, of the army of General Feng Yuxiang.

(Photo: Philip Jowett Collection)

This armoured train was the escort for the special train which transferred the remains of Sun Yat-sen23 when his ashes were repatriated from Beijing to Nanking in June 1929.

(Photo: Paul Malmassari Collection)

During the war between Chiang Kai-shek, Feng Yuxiang and Yan Xishan, known as the ‘War of the Central Plains’, many battles between armoured trains took place. According to contemporary documents, the two principal objectives of the armoured trains were to silence or destroy enemy trains and to act in support of the infantry, missions which closely followed the classic role of the armoured train. On 24 May 1930 a typical battle took place, as described by General Xu Tingyao of Chiang Kai-shek’s forces:

During the fighting on the Longhai railway line, I was second-in-command of the 1st Division, and I was responsible for the leading echelon of the attack. An enemy armoured train, the Zhongshan, was positioned on the line and completely blocked our advance, which caused me a great deal of anxiety. Later I recovered two trains, the Yun Gui [the Provinces of Yunnan and Guizou] and the Chan Cheng [Great Wall]. These armoured trains could not match the enemy train in terms of firepower, but had more powerful engines. Thus I conceived the plan to combine our two trains – making a total of four engines – then to ram the enemy train with two engines, to couple it up and drag it back to our lines. I climbed aboard the leading train and personally supervised the operation. The enemy crew spotted our trains and fired on us without hitting us. Our own fire was also unsuccessful. However, when our trains came within 400m [almost 400 yards] of the enemy train, two shells struck our leading train, causing many casualties and appearing to knock it out of the fight. I therefore dis-embarked to lead the troops on the ground. The enemy train continued to fire and I was severely wounded by the explosion of a shell beside me.

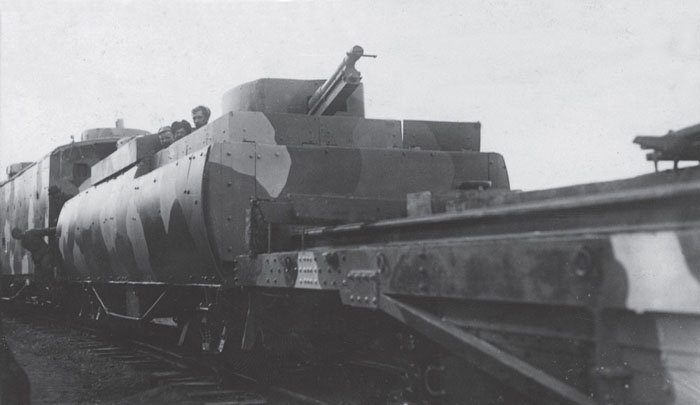

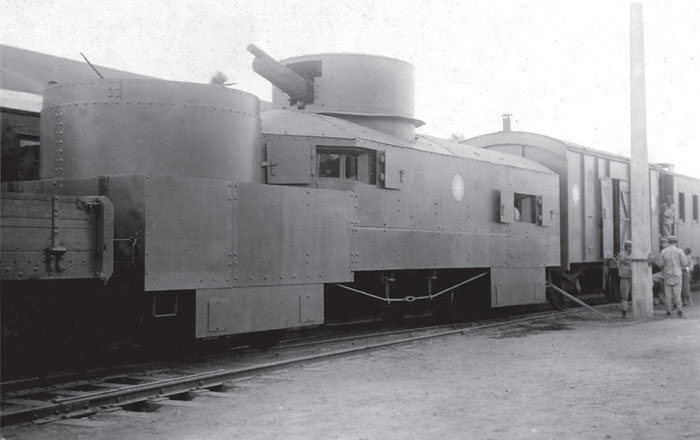

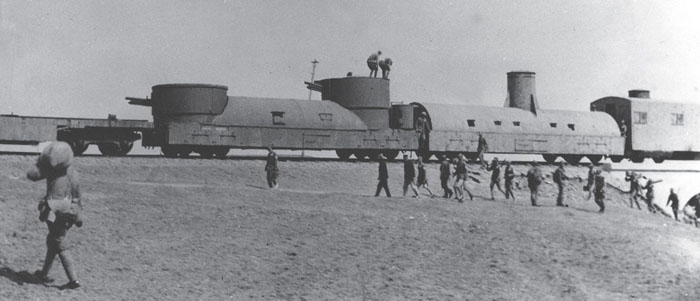

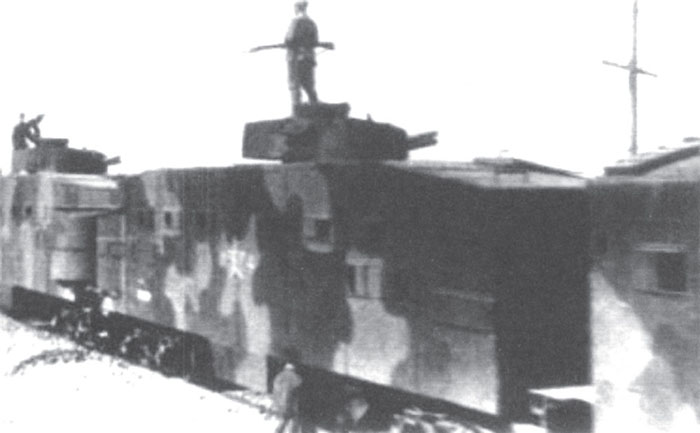

While the different factions were fighting each other in Central China, the Fengtian forces (the future Army of the North-East) had put together a formidable force of armoured trains in north-east China. As with the trains of the Kuominchun, details are hard to come by. Nevertheless, by the beginning of the 1930s, the Fengtian trains demonstrated remarkable features. Their main characteristic was the semi-cylindrical form of the artillery and infantry wagons, which provided superior protection compared with previous Chinese armoured trains. In addition, the ex-White Russian armoured trains were also used by the Army of the North-East. The armoured trains were in the vanguard when the Army of the North-East conquered Peiping and Tientsin under the command of Marshal Zhang Xueliang, thus putting an end to the war of the Central Plains.

The characteristic form of the Fengtian trains is well in evidence here, with their semi-cylindrical shape topped by turrets or an observation tower.

(Photo: Paul Malmassari Collection)

They also fought the Japanese during the Manchurian incident in 1931, and showed themselves to be as effective as contemporary Japanese trains. Later, several were obliged to withdraw to the south to the areas still held by Chinese troops, such as Peiping and Tientsin.

(Photo: All Rights Reserved)

An armoured train photographed near Shanghai in 1932. Note the unusual profile of the artillery wagon, which allows a wide field of vision for the armoured observation cupola on the following wagon.

(Photo: Paul Malmassari Collection)

Armoured Train Chang Jiang, with a wagon the hull of which is identical to that in the previous photo, but with a single gun protected by a shield which appears to be open at the rear. Note the hand trolley carried on the flat wagon.

(Photo: Paul Malmassari Collection)

37mm Type 94 gun mounted aboard a Chinese armoured train captured by the Japanese.

(Photo: Paul Malmassari Collection)

Communist armoured train on the Hunan-Guangxi line in 1949. The Japanese wagons have been modified to carry turrets from Type 97 Chi Ha tanks,24 but armed with 57mm Type 97s in place of the 47mm gun normally mounted. It appears that a cylindrical nacelle has been fitted to the left-hand wagon.

(Photo: Yichuan Chen Collection)

On the Nationalist side, from 1930 onwards there was virtually no renovation of the fleet of armoured trains, and their importance declined. The Chinese armoured trains, once a formidable force, had ceased to be the principal arbiter of the battlefield. They played a minor role during the war against the Japanese between 1937 and 1945. From the photographic record, the Chinese trains of that period were either the former trains of the Army of the North-East or ex-White Russian trains.

When the civil war between Nationalists and Communists began in 1946, Chinese armoured trains seem to have undergone a renaissance. As the Communists’ principal tactic against the Japanese had been the destruction of the railway lines, they continued this against their new adversary, while the Nationalists inherited the tactics and the techniques of defence of the railway network from the Japanese, and even several Japanese armoured trains. From late 1947, the Communists began their counter-offensive with attacks against the cities held by the Nationalists. At that time the Nationalist armoured trains, rather than patrolling the railway network, were frequently used as a mobile force within the defensive systems of the cities. One of the first confrontations between the Communist besiegers and an armoured train took place in November 1947 during the battle for Shijiazhuang. The Nationalist force was composed of between four and six trains, including one of Japanese origin. The remainder were improvised from goods wagons and flat wagons reinforced with concrete and steel plates, often considered as being better protected than the Japanese trains, and carrying tanks. To fight them, the Communists employed captured weapons which were new to them, such as bazookas and anti-tank guns. Similar fighting occurred during the sieges of Jinan, Tianjin (Tientsin) and Taiyuan.

The last chapter in the history of armoured trains in China was written by the Chinese Communists. In the late 1940s and early 1950s, a few armoured trains were retained in service to guarantee the security of the rail network against bandits. In July 1951 all the armoured trains from the different regions of China were recalled and stocked at Shenyang. Their crews were distributed among infantry units and sent to Korea. Thus ended the thirty-year history of armoured trains in China.

Communist armoured train in north-east China, also converted from former Japanese wagons, on which armoured cupolas have been installed. These hemispherical cupolas were originally from bunkers, some of which are today on public display in the Museum of the Battery of the West at Yingkou (Liaoning Province).

(Photo: Yichuan Chen Collection)

Nationalist armoured train derailed during the battle for Taiyuan in 1949. The turret is armed with a 75mm mountain gun.

(Photo: Yichuan Chen Collection)

A Nationalist armoured train captured during the battle for Taiyuan. Originally a Japanese safety flat wagon, the wagon shown in the centre has been converted by adding wooden walls pierced by loopholes.

(Photo: Yichuan Chen Collection)

This scene purporting to show an armoured train captured by the Communists in the Shanxi has perhaps been posed for propaganda purposes, but it illustrates the method of attack in those zones where it was possible to dominate the trains from high ground.

(Photo: Yichuan Chen Collection)

This Nationalist armoured train was captured during the Zheng-Tai campaign in 1949 on the Zhengding-Taiyuan line. Note the familiar form of the ex-Japanese safety wagon with its armoured lookout cabin.

(Photo: Yichuan Chen Collection)

SOURCES

Books:

Jowett, Philip, The Armies of Warlord China 1911-1928 (Altglen, PA: Schiffer Publishing, 2014).

___________, China’s Wars: Rousing the Dragon 1894-1949 (Oxford: Osprey Publishing, 2013).

Krarup-Nielsen, Aage, The Dragon Awakes (London: J. Lane, 1928).

Malraux, André, La Condition humaine (Paris: Gallimard, 1933).

Journal Articles:

‘Chine: Trains blindés’, Revue d’Artillerie Vol 99 (January–June 1927), pp 694–5.

Girves, Captain, ‘La Guerre civile en Chine’, Revue militaire française Vol 1 (1927), p 190.

‘Manchurian Armored Train’, Coast Artillery Journal (USA) Vol 66, No 5 (May 1927), pp 481–2.

Rouquerol, General J, ‘Chine: Les trains blindés en Asie Orientale’, Revue d’Artillerie (July–December 1927), pp 605–9.

Zaloga, Steven, ‘Armour in China’, Military Modelling Manual (1983), pp 4–9.

Website :

http://www.chinaheritagequarterly.org/features.php?searchterm=sapajou_page12.inc&issue=022

Film:

Russian-made film of the advance of the forces of Marshal Chang Tso-Lin, Warlord of Mukden, South towards Nanking, 1924-1925. (1925), IWM 172.

An interesting view of a Communist armoured train used for track repairs, with the red star surrounded by the slogan ‘Our work takes us where the frontiers lie’.

(Photo: Yichuan Chen Collection)

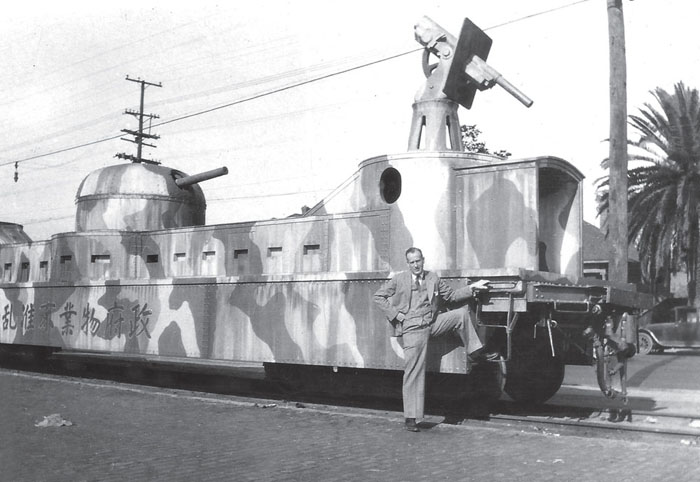

This photo is not what it seems. Here is film star George Sanders with a ‘Chinese armoured train’ from the 1938 Hollywood film International Settlement, set in Shanghai. The ideograms on the side of the wagon read ‘Government Property Do Not Touch’. Sadly, the scene with the armoured train seems to have ended on the cutting-room floor, so this is the only surviving record.

(Photo: Paul Malmassari Collection)

1. This war which lasted one week in July 1920, between the two rival factions named for the respective provinces of their leaders (today in the region of Hebei), was fought to control the Chinese government in Beijing: the Zhili faction came out the winner.

2. Nicolai Merkulov was a merchant who, along with his brother Spiridon Dionisovich, headed the short-lived Government of Pryamure (from May 1921 to October 1922), the last White enclave in Siberia.

3. A conflict which was started by the coup d’etat of General Feng Yuxiang in Beijing.

4. Refer to the Sources at the end of this Chapter, for the film which was produced on that occasion, preserved in the Imperial War Museum. In it one can see that the artillery component was a 75mm Japanese Type 41 mountain gun or a Type 6 (the special version built for China).

5. The first ferryboat was not imported from England until 1933.

6. Provincial Governor.

7. Respectively: Mount Tai, Shantung, the regions of the Provinces Yunnan and Guizhou, Ho Nan. It is difficult to know whether the armoured trains of the same name photographed several years later were the same ones, modernised, or completely different trains.

8. The White Russian armoured trains were commanded by a certain Tchekov.

9. Described in ‘Manchurian Armored Train’, Coast Artillery Journal (USA), Vol 66, No 5 (May 1927).

10. A Nationalist Army created in 1924 and commanded by Feng Yuxiang.

11. This campaign carried out between 1926 and 1928 by the Kuomintang, commanded by Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek, had as its objective the reunification of China, which was completed by October 1928, with Nanking as capital.

12. Certain sources believe that Jin Yun-é was secretly preparing to negotiate with the Nationalists.

13. Depending on which historical period is under consideration, the term ‘Nationalist’ could also be applied to the Communist forces, since their objectives and those of the Kuomintang included opposition to the Warlords. Chiang’s rupture with the Communists and his war against them began in April 1927.

14. Soviet advisers had been sent by the Comintern as early as 1923.

15. Recorded in the archives preserved in Taiwan.

16. The central element of André Malraux’s novel La Condition Humaine.

17. ‘Zhong Shan’ was the most famous surname of Sun Yat-sen, given to him by the Japanese philosopher Töten Miyazaki, one of Sun’s supporters during the Revolution.

18. Today in the District of Pukou, Nanking.

19. Today in the County of Fengyang, in the town of Chuzhou.

20. Which linked Beijing to Hangzhou, built between AD 605 and 609.

21. To the south-west of Nanking. The name literally means ‘horse saddle mountain’.

22. More likely vodka.

23. 12 November 1866 – 12 March 1925, he was one of the founders of the Kuomintang, and in 1912 had become the first President of the Republic of China. In June 1929 his ashes were buried in the mausoleum specially built to receive them.

24. Known as Gongchen in China.