Beginning in 1894, in moves to establish footholds and expand territorial gains on the continent of Asia, the Japanese Empire became embroiled in several conflicts, firstly with the Chinese Empire, and then with the Republic of China. Amongst other territorial gains, the Sino-Japanese War of 1894–5 gave Japan Formosa and Port Arthur in Manchuria. Korea became a Japanese colony. Then Japan participated in the Allied intervention in Siberia from August 1918 to October 1922. In 1931 Japan conquered Manchuria and renamed it Manchukuo. Finally, the Second Sino-Japanese War which broke out in 1937 became part of the wider Second World War.

As for Japanese armoured trains, from 1918 they intervened in Siberia, in 1931 in the invasion of Manchuria, then in 1932 in the move against Shanghai, and finally across the whole of occupied Chinese territory. After the Japanese defeat in 1945, Japanese armoured trains were used by Chinese forces during the Chinese Civil War, and perhaps even in Korea.

Japan intervened in the Russian Civil War as part of an international force totalling 25,000 men. The Japanese first went into action in Siberia in July 1918 at the request of the American government, with the despatch of an initial contingent of 12,000 men under Japanese command.1

Once the troops were in place, the security of the railway network was assured by armoured trains, most of which had been brought to the region by the withdrawing Czech Legion. The Japanese, however, refused to become involved to the west of Lake Baikal, and their priority was basically to support the White Generals Ataman Semyonov and General Kalymkov, who themselves were well-equipped with armoured trains, and then later General Baron von Ungern-Sternberg.

On 5 April 1920 the Japanese contingent, the sole non-Russian force remaining after the withdrawl of the American contingent,2 launched an offensive to disarm the local revolutionary forces, with the ultimate aim of protecting the Japanese Home Islands, as well as its colonies in Korea and Manchuria, against the threat of the anti-monarchist Bolsheviks. The Japanese crossed the Transbaikal, withdrew their support from Semyonov, and finally in October 1922, giving in to international and domestic3 pressure, withdrew their troops.

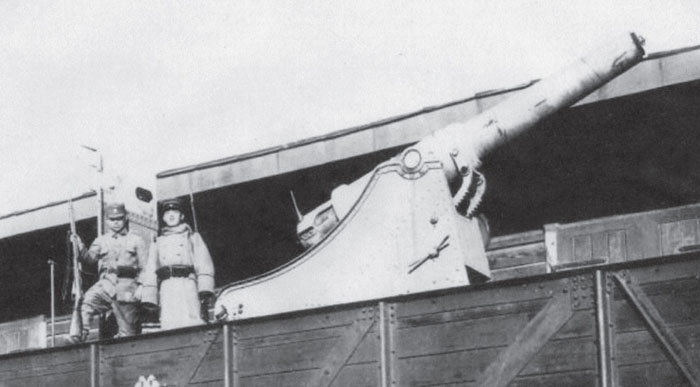

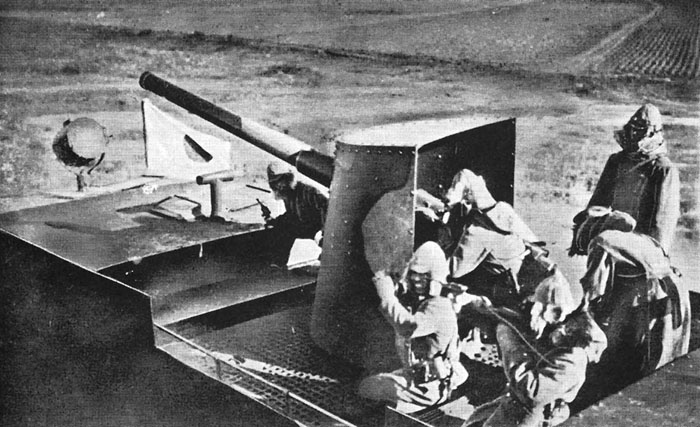

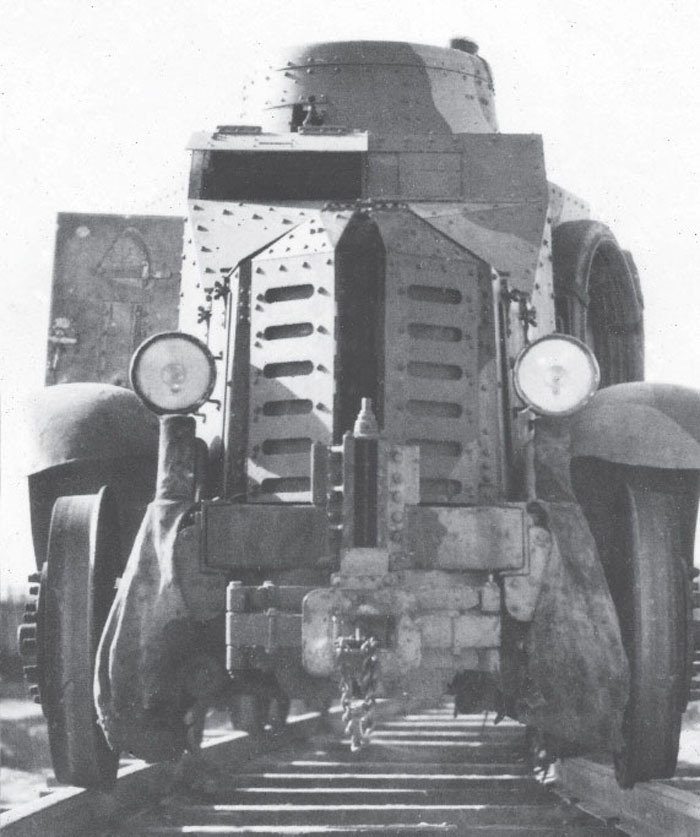

This gun crudely placed on an elevated platform, installed aboard a Russian bogie wagon and allowing for only head-on fire, appears primitive in comparison with other contemporary armoured trains with guns in turrets.

(Photo: Paul Malmassari Collection)

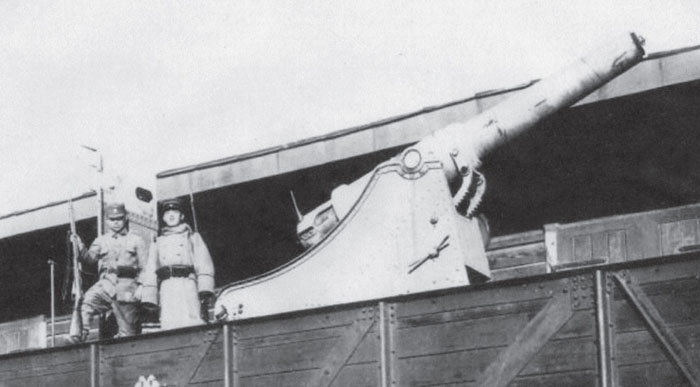

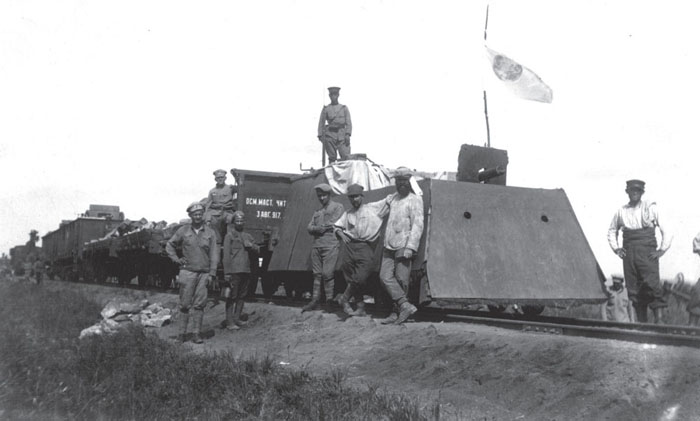

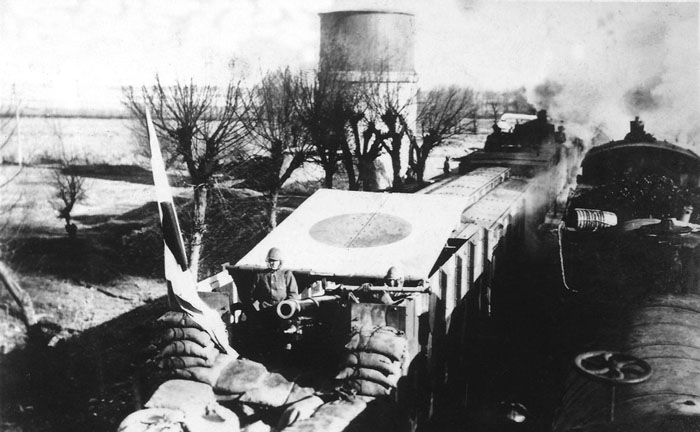

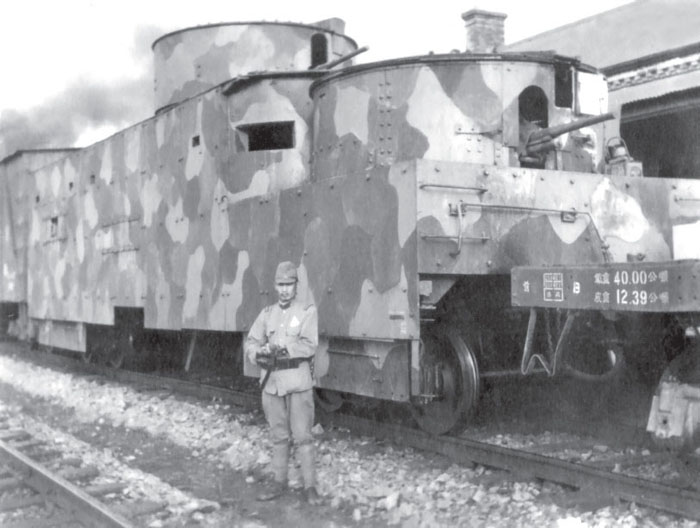

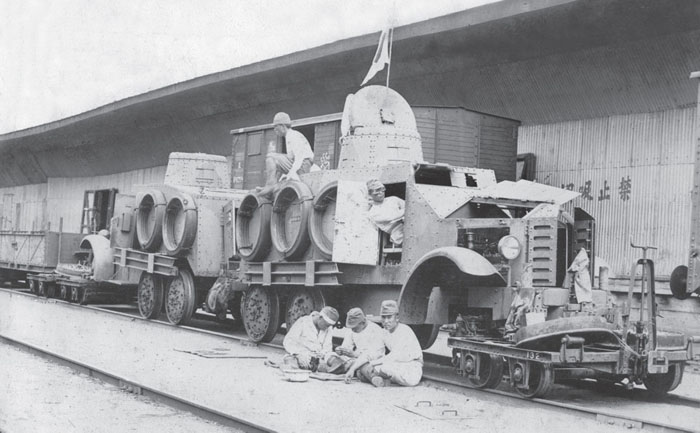

More in keeping with the standards of the day, this train which flies the Hinomaru, the Japanese flag,4 is built on the base of a classic Russian railways’ bogie wagon.

(Photo: Paul Malmassari Collection)

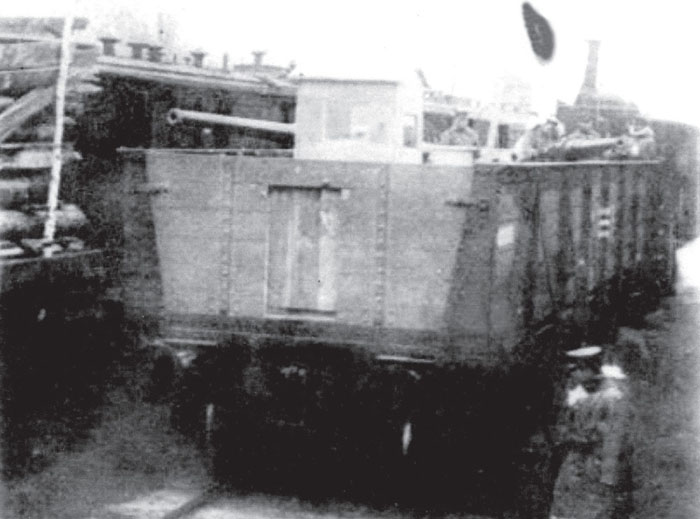

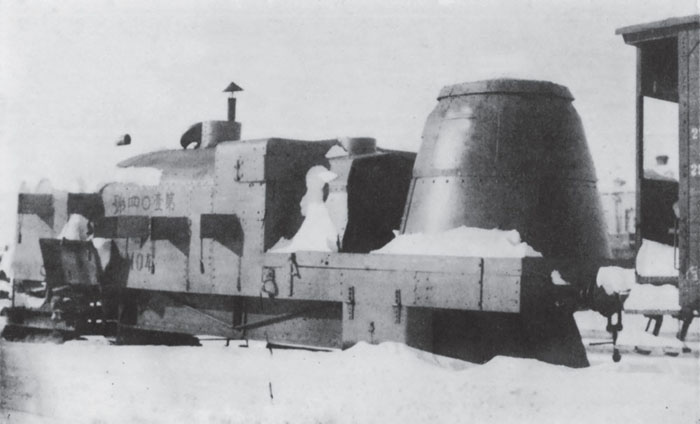

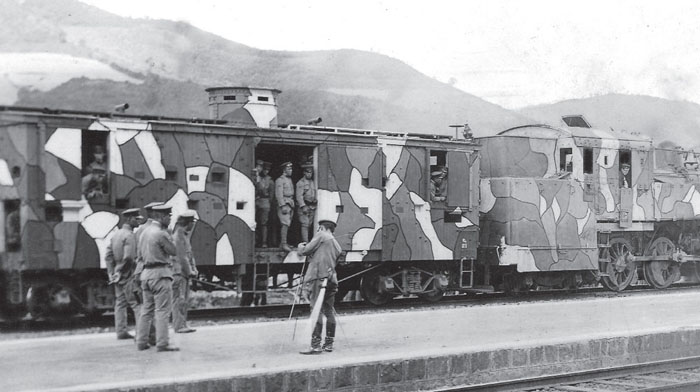

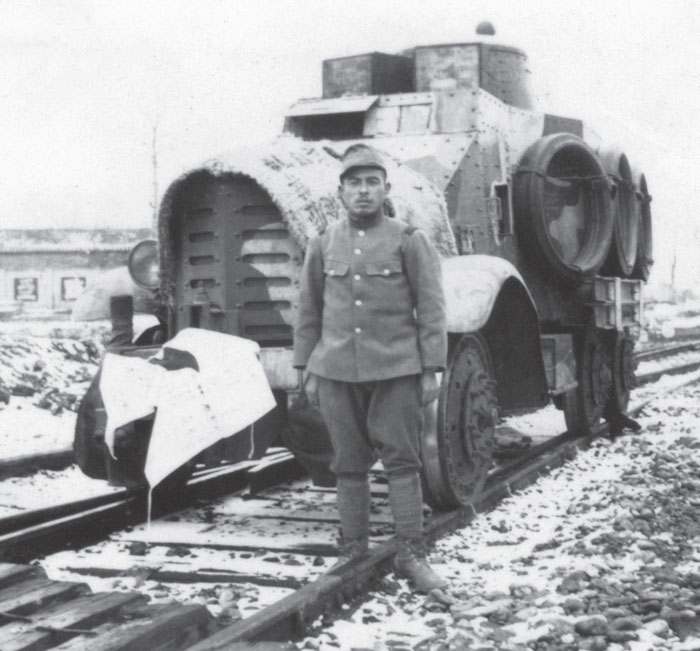

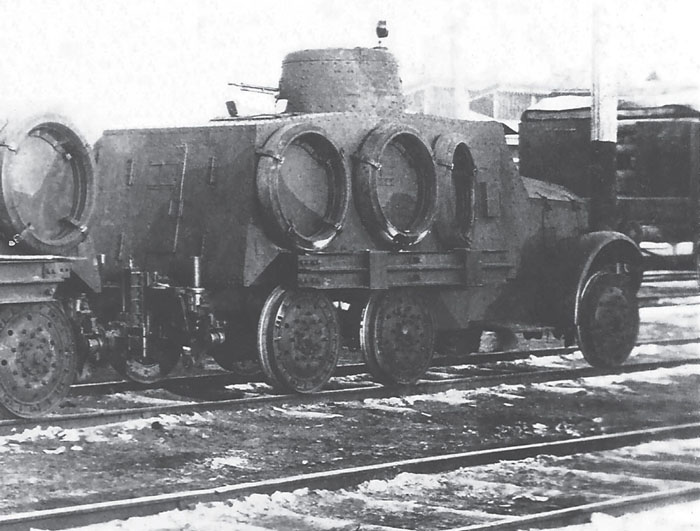

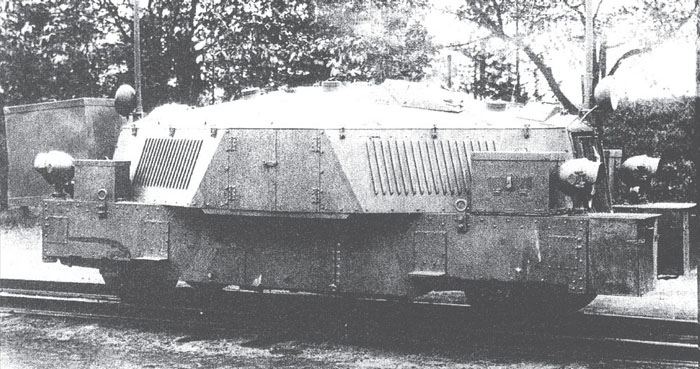

This Japanese armoured wagon built on a Russian bogie wagon has rudimentary armour protection, but its armament is impressive.

(Photo: Paul Malmassari Collection)

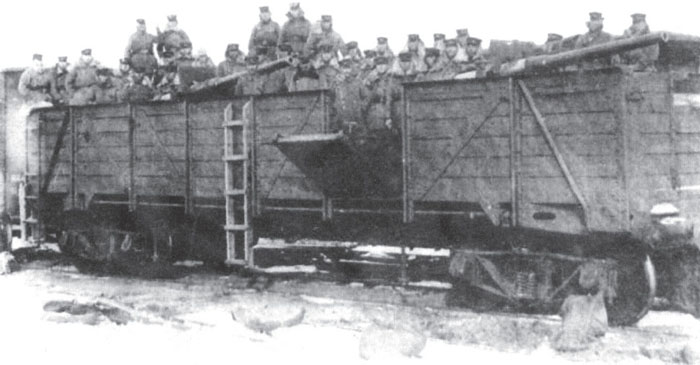

A well-known photo of an interesting machine-gun wagon, with a mixed Czech and Japanese crew, typical of the forces defending certain sections of the Trans-Siberian Railway.

(Photo: All Rights Reserved)

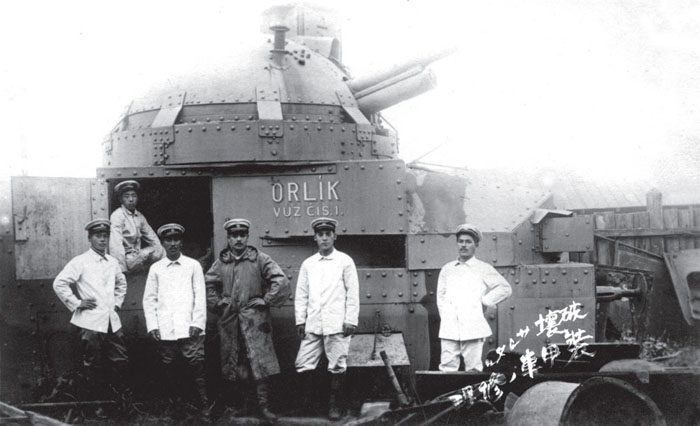

A close-up of one end of the railcar of Orlik, which still bears its Czech name, with the inscription ‘VUZ CIS.1’ meaning ‘Wagon No 1’.

(Photo: Paul Malmassari Collection)

The artillery wagon of Orlik, here in Japanese hands, as shown by the inscription painted on the sides. The gun is a 76.2mm Russian Model 1902 in a turret with a horizontal field of fire restricted to 270 degrees due to the armoured superstructure.

(Photo: Paul Malmassari Collection)

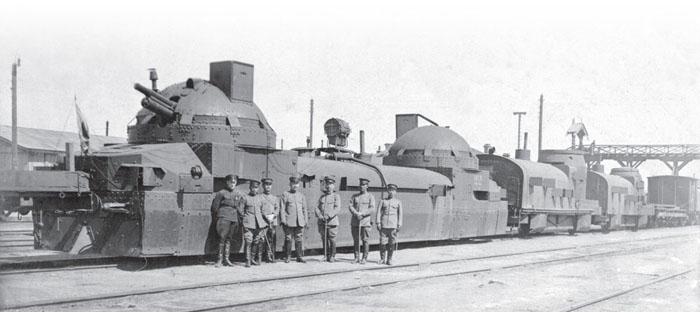

A fine view of the armoured railcar which operated with, or independently of, the armoured train Orlik. Note the Czech officer on the left, with a group of Japanese officers. Note also the latest modifications such as the searchlight mounted on the roof.

(Photo: Paul Malmassari Collection)

This photo shows the ultimate appearance of a Russian armoured wagon, formerly part of Kalmykov’s forces but now taken over by the Japanese. Note the ‘Japanese touch’ of the additional armour, and in the overall arrangement of the train, which appears less haphazard than in its original version.

(Photo: All Rights Reserved)

A fine photo of a Japanese armoured trolley in service in Siberia. It is surrounded by Czech Legionnaires.

(Photo: Vojenský ústředni archive-Vojenský historický archive)

The civil war which began in 19115 had left China fragmented. In Manchuria, where Japanese influence had replaced that of the Russians since the war of 1905, on 18 September 1931 minor damage caused to a railway line6 passing close by a Chinese garrison, in what became known as the ‘Mukden Incident’,7 gave Japan the excuse to strengthen its hold by launching an invasion.8 By occupying Harbin on 5 February 1932, the Japanese completed their military conquest of Manchuria, one of the major Chinese provinces situated well to the north of the original Japanese zone of influence. Subsequently, on 18 February 1932 the Japanese created the puppet state of Manchukuo, ruled by Pu Yi, the last Emperor of China, which would never be recognised by the League of Nations.

In 1928, the Japanese had assembled six armoured trains in Manchuria, armed with 75mm Model 41 mountain guns. But following the Mukden Incident, the Railway Company of the Kwantung Army was created specifically to commission armoured trains and take over responsibility for their technical aspects. Alongside the growing number of armoured trains, ‘guard trains’ were brought into service, the latter composed of just one infantry wagon coupled to an artillery wagon. In addition, armoured wagons crewed by veterans of the Manchurian Railway Company were coupled in with scheduled trains. Thus by 1935, the Kwantung Army had a total of twenty-eight armoured trains and four guard trains.

A lack of detailed records prevents us describing all the actions in which armoured trains participated during the campaign, but several typical engagements were reported in the newspapers of the time. Although the Chinese Army in Manchuria had retreated in disorder, the railway lines were by no means secure. For example, on 15 November 1931, when the Japanese tried to outflank the Chinese lines near the bridge over the River Nonni, Chinese cavalry succeeded in cutting off the troop detachment which had disem-barked from their armoured train, and only a few of the Japanese succeeded in rejoining the train, under the covering fire of its guns.

The whole of Manchuria was nominally occupied by the Japanese, but they in fact controlled only the towns and the railway lines, along with a large part of the Chinese Eastern Railway. The Japanese presence obliged the Russians to maintain 150,000 men along the length of the frontier between Vladivostok and Manchuli (the station closest to the Manchurian frontier). The Japanese garrison, in addition to tanks and artillery, maintained some thirty armoured wagons.

In reprisal for a boycott of Japanese goods by the Chinese authorities in response to the invasion of Manchuria in early February 1932, the Japanese decided to take military action in Shanghai. The Chinese resisted the Japanese aggression and among other means, brought an armoured train into use on the Shanghai-Nankin line, operating principally by night, and added armoured wagons to their troop trains. It appears that their use ceased once the Japanese landed heavy artillery.

On 7 July 1937 the Marco Polo Bridge Incident between Chinese and Japanese troops led to the outbreak of the Second Sino-Japanese War on the 28th of the same month, in which the Japanese captured several Chinese cities. In March 1940 a Central Chinese Government was installed by the Japanese, but the war gradually developed into a series of guerrilla and counter-guerrilla actions. This conflict ended on 8 August 1945 with the Japanese surrender,9 the occupation of Korea by Soviet forces and the outbreak of a new civil war in China.

The lack of good roads in this immense territory meant that the railways were vitally important. The Japanese deployed large numbers of troops to protect the railways, and in turn these became a principal target for sabotage. The Imperial Army used several armoured trains10 and armoured trolleys. These units were obliged to operate over two different rail gauges depending on the area: 1520mm (5ft nominal) Russian gauge in the northern zone of Manchuria, and 1435mm (4ft 8½in) European gauge in the rest of the territory.

The first Japanese armoured trains, which according to Antoine Baseilhac ‘represented the only highly mobile powerful elements across the vast Manchurian plains’, were improvised from existing Manchurian rolling stock. They also used elements of captured Chinese armoured trains, which were often better constructed, many being former White Russian armoured trains brought to China when the Whites had fled Russia at the end of the Civil War. But to meet the need for modern equipment, two unique designs of armoured train were built for use in Manchuria: the Temporary Armoured Train in 1932, and the following year the Type 94 Armoured Train. At the same time, a large number of self-propelled units were put into service for use by rail reconnaissance patrols.

.

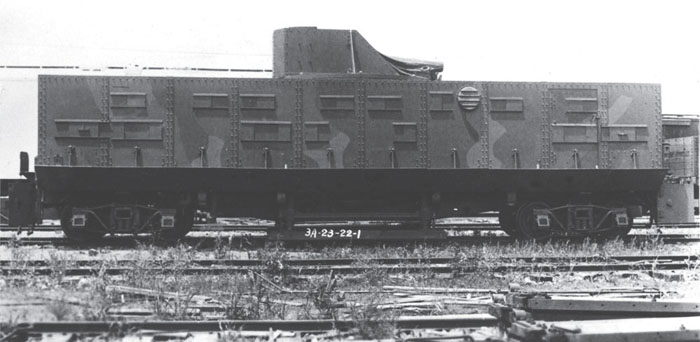

This type of armoured wagon is typical of the Korean or Manchurian railway network. Its construction is straightforward, with an armoured body attached to a standard bogie flat wagon which is the same as in preceding photos.

(Photo: Konstantin Fedorov, Archivist, Collection)

A view of the other end of the wagon.

(Photo: Konstantin Fedorov, Archivist, Collection)

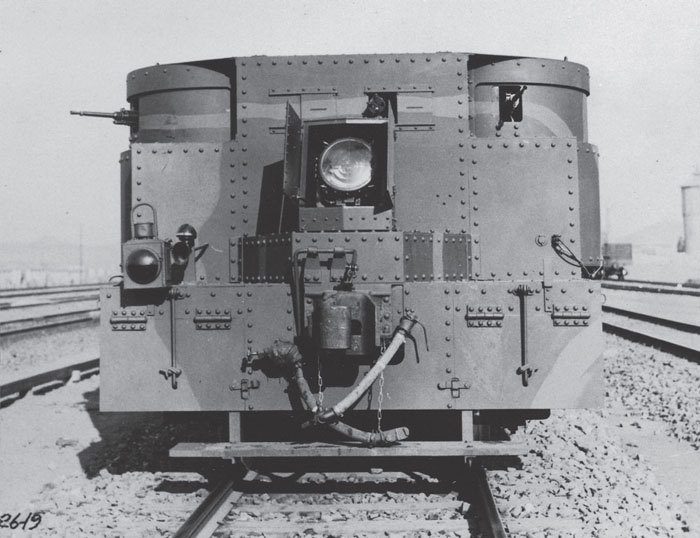

This photo should be compared to that shown in the chapter on South Korea (1950–3). The arrangement of the opening flaps on the firing nacelle is interesting, as is the tripod fixture for a searchlight on the roof. In fact, this photograph viewed in conjunction with the preceding two proves that the nacelles were diagonally offset.

(Photo: Paul Malmassari Collection)

Similar construction features are evident on other armoured trains, here lacking lateral MG nacelles. Note the front observation position separated from the main armoured hull.

(Photo: Paul Malmassari Collection)

Another similar view – perhaps the other end of the same train, showing the various different types of protection, riveted plates, welded plates, sandbags, etc.

(Photo: Paul Malmassari Collection)

In these photos, we can see dark rectangles painted as a ‘trompe-l’œil’ to represent false firing ports.

(Photo: Paul Malmassari Collection)

In addition to armoured wagons intended to be included with normal trains, the Japanese put together armoured trains intended for offensive patrols. Here, the pilot/safety wagons have been uncoupled. The insignia on the side of the armoured wagon is that of the military railways.

(Photo: All Rights Reserved)

A different type of pilot/safety wagon, equipped with an armoured cabin for close observation of the track. The design of these cabins varied considerably, and there seems to be no standard pattern.

(Photo: Paul Malmassari Collection)

Two photographs of a typical armoured train on the Manchurian front. In this view, the train is lacking an artillery wagon which would normally be coupled to the wagon in the foreground.

(Photo: Paul Malmassari Collection)

Probably an earlier design of pilot/safety wagon, since the second wagon is a Russian high-sided bogie wagon of the type used during the Russian Civil War.

(Photo: Heiwa Kinen Tenji Shiryokan)

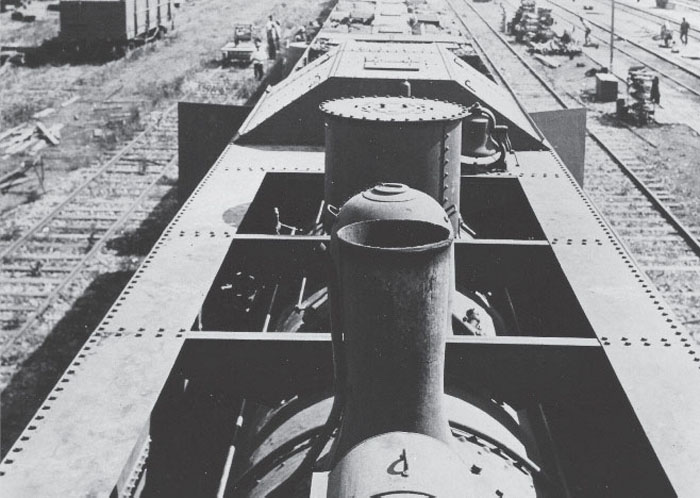

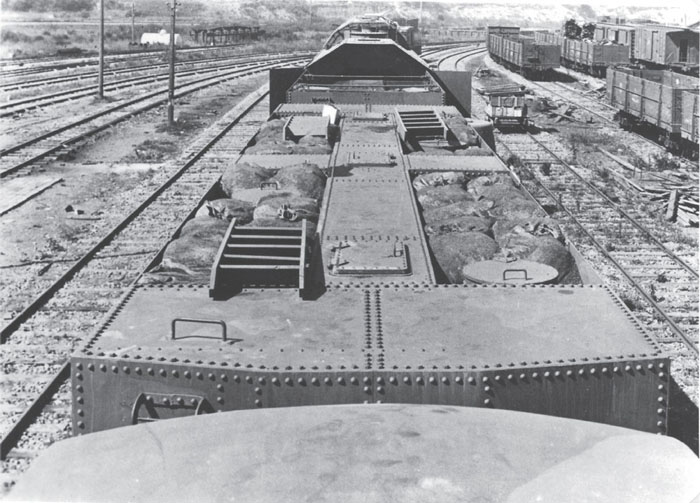

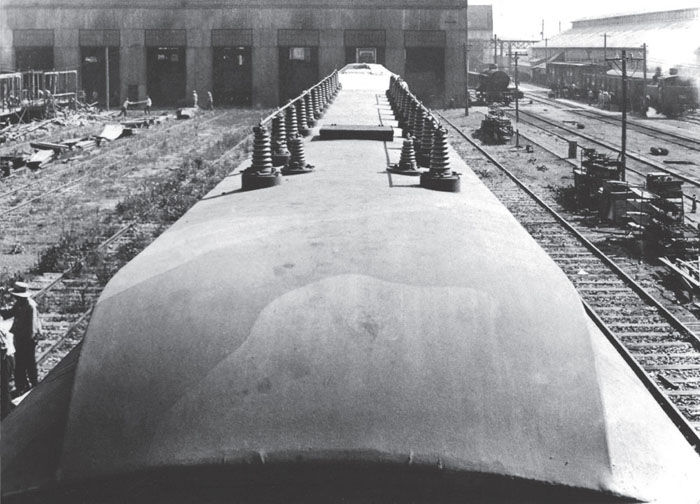

A view looking down on an artillery wagon, which would serve as the inspiration for a number of subsequent illustrations. For examples, see Appendix 1.

Here is the front part of the same train showing the partial protection on the engine, but with a fully-armoured cab fitted with a sliding blind. The gun appears to be a 75mm Type 41 (1908).

(Photo: Paul Malmassari Collection)

Another tactical feature of these trains is shown here: to provide sufficient water for the engine, a bogie tank wagon was inserted between the tender and the artillery wagon.

(Photo: Paul Malmassari Collection)

Here the horizontal board serves both as protection from the elements and as a recognition feature for Japanese aircraft. This photo was the inspiration for the postcard shown in Appendix 1.

(Photo: Paul Malmassari Collection)

The Japanese also put into service armoured trains on the narrow-gauge or metric lines within their occupied territory. These two views show two trains of this type, with a gun in a turret and with armour obviously tailored to the contours of the wagons. But it is just possible that these show a training unit (white armbands, irregular form of the armour etc)

(Two Photos: Wawrzyniec Markowski Collection)

Japanese protection wagon, converted from a van, seen as part of an unarmoured train photographed at Tientsin in August 1937. It is armed with a 6.5mm Type 11 light machine gun.

(Photo: Paul Malmassari Collection)

Another van roof fitting seen in Manchuria, this time armed with a 6.5mm Type 3 heavy machine gun. The lack of the special ring sight would suggest this is not meant for anti-aircraft protection.

(Photo: All Rights Reserved)

In the course of their offensive, several Chinese armoured trains were captured by the Japanese and were immediately put back into service, as we can see in this photo, where the side of the wagon to the right bears Japanese markings. For other views of these units, refer to the chapter on China.

(Photo: Paul Malmassari Collection)

An imaginative postcard issued by an anti-aircraft unit, their stamp bearing two AA guns, a searchlight beam and sound locators. In fact the Chinese air force put up little real opposition.

(Postcard: Paul Malmassari Collection)

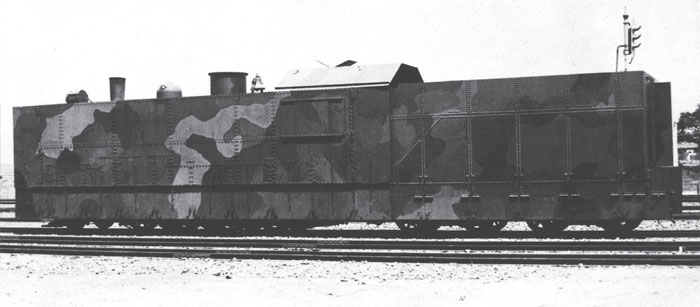

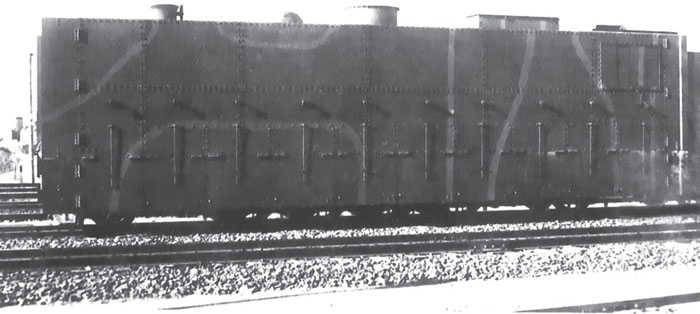

‘Temporary Armoured Train’ was the official name given to this type of train, which was designed in 1932 as an experiment for service in Manchuria. In all, three of these trains were built, the first one being completed in July 1933. They were operated by the 3rd and 4th Railway Regiments. Each train was made up of the following elements:

– Pilot (track control) Wagon.

– Heavy Artillery Wagon.

– Light Artillery Wagon.

– Infantry Wagon.

– Command Wagon.

– Tender Engine.

– Auxiliary Tender.

– Technical Equipment Wagon.

– Infantry Wagon.

– Light Artillery Wagon.

– Howitzer Wagon.

– Pilot (track control) Wagon.

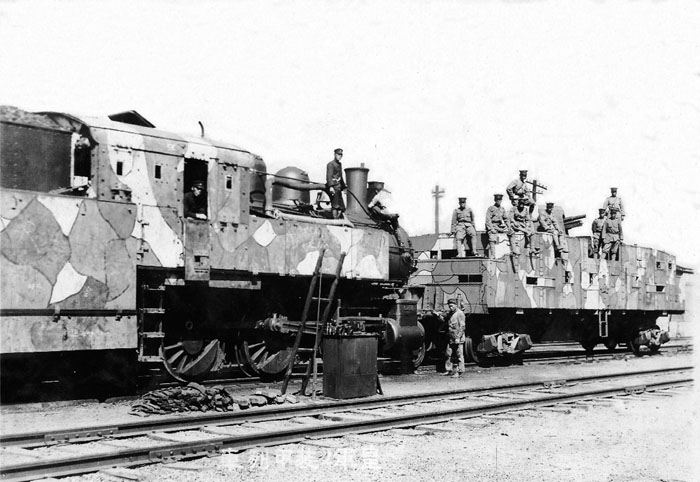

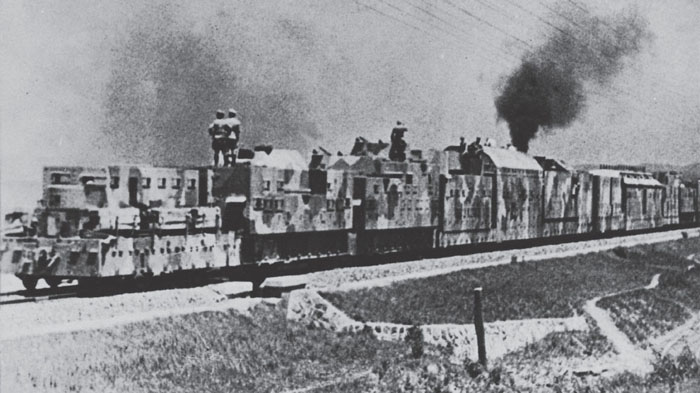

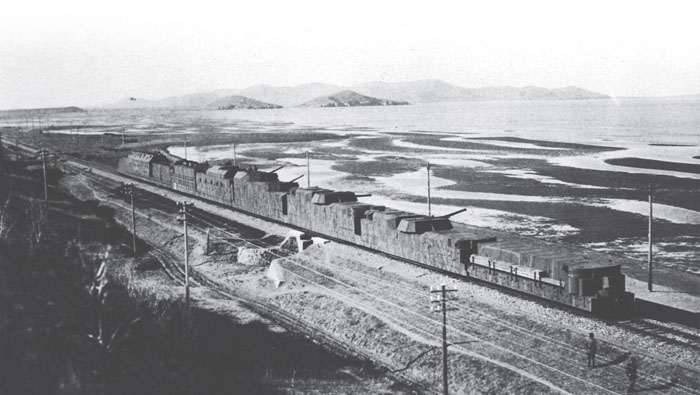

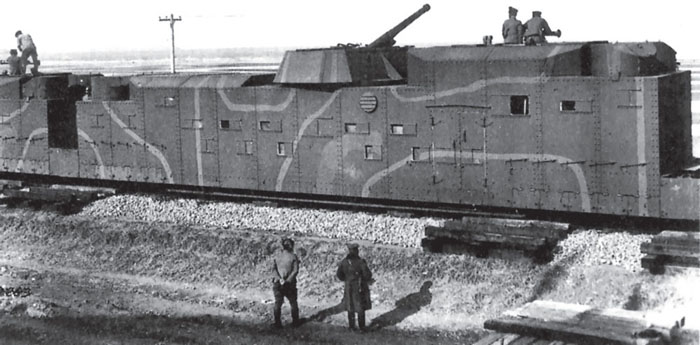

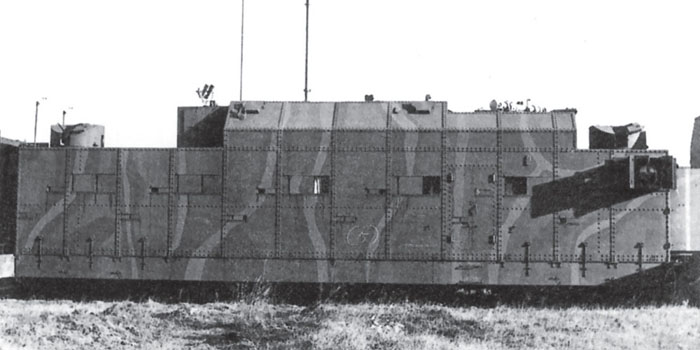

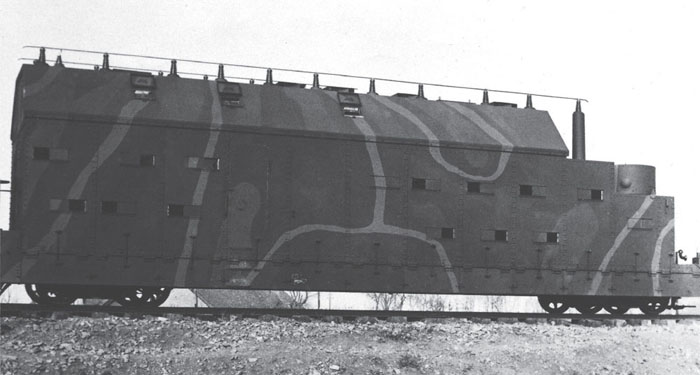

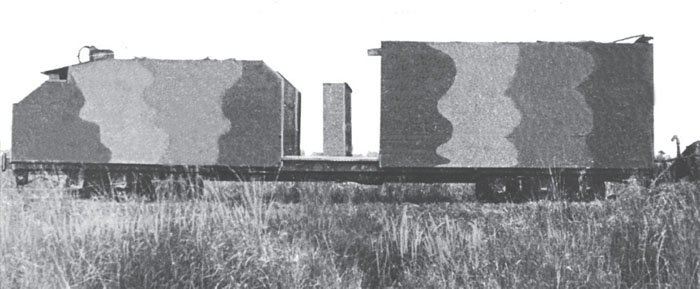

An overall view of the train, demonstrating the typical camouflage used on the Chinese front. Immediately obvious from this photo is the degree to which the plume of smoke from the engine, when it is not diverted to track level or otherwise dispersed, gives away the precise location of the train to enemy observers.

(Photo: All Rights Reserved)

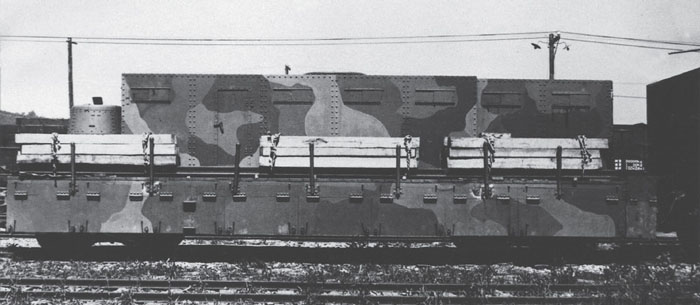

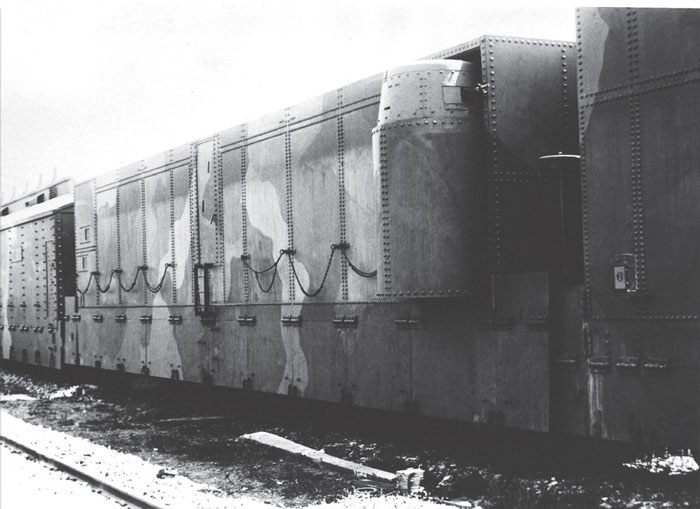

Of note are the rails and sleepers attached to the sides of the wagon, and the well-executed camouflage scheme.

(Photo: All Rights Reserved)

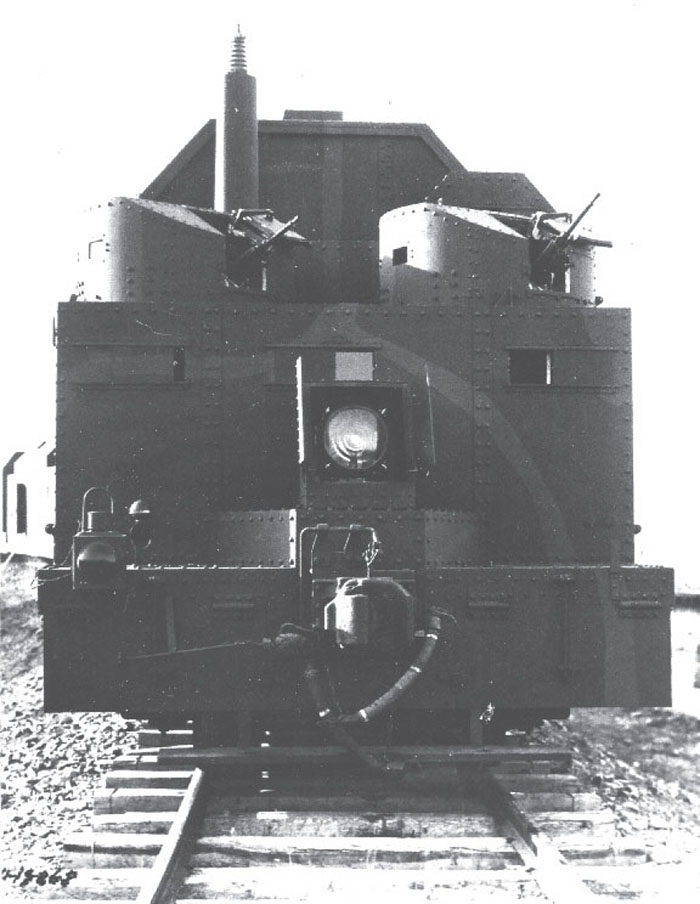

One of the Pilot (track control) Wagons, built on a 30-tonne bogie platform wagon, with its turret for close-in defence, armed with a 6.5mm Type 11 LMG. The two armoured doors protect a 60cm diameter searchlight.

(Photo: All Rights Reserved)

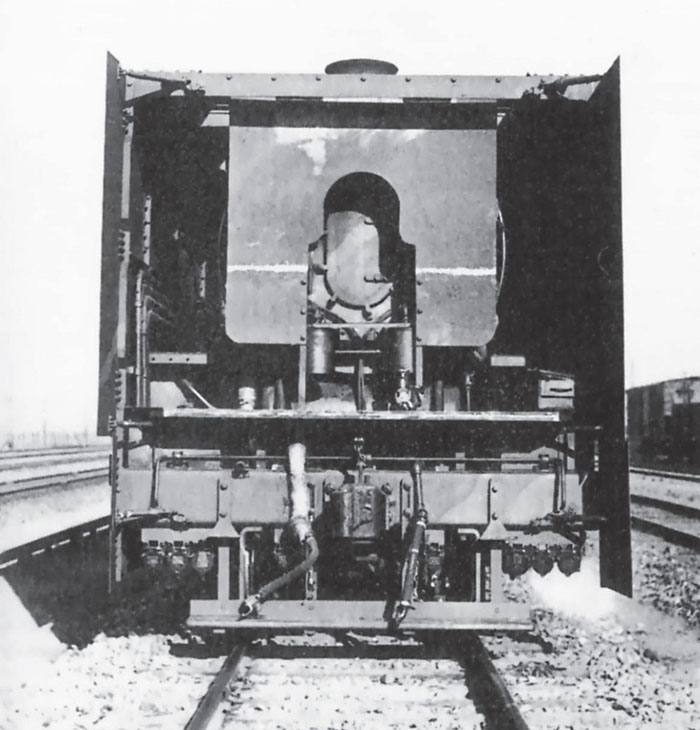

The leading Artillery Wagon of the Heavy type, with its 100mm Type 14 anti-aircraft gun, in a turret with all-round traverse, and supplied with 500 shells. Its additional armament was composed of a heavy machine gun and ten rifles, served by a crew of one officer and fourteen men. Here the lower armour plates have been hinged upwards, allowing us a view of the means of stabilising the wagon when firing. Also visible are the seemingly excessive number of firing ports, closed by sliding shutters – although the total would allow for the full crew to bring their weapons to bear on one side.

(Photo: All Rights Reserved)

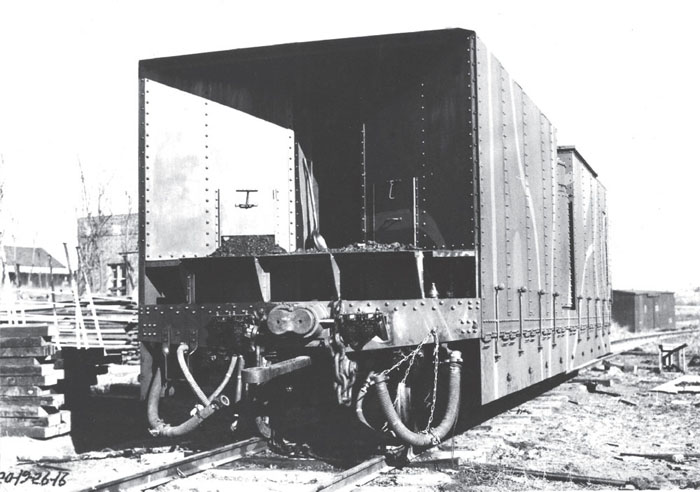

The same comments apply to the Light Artillery Wagon, whose crew of one officer and nineteen men served the two turrets, each mounting a 75mm Type 11 gun, supplied with a total of 500 rounds. The base for both units was the Type Ta-I 50-tonne coal wagon.

(Photo: All Rights Reserved)

A bogie platform wagon formed the base for the Infantry Wagon. Each turret was armed with a 13mm Type 92 HMG. The armament also included two 6.5mm Type 3 MGs (also known as the Taisho 14), two Type 38 rifles and a 30cm diameter searchlight. The crew consisted of one officer and eleven men.

(Photo: All Rights Reserved)

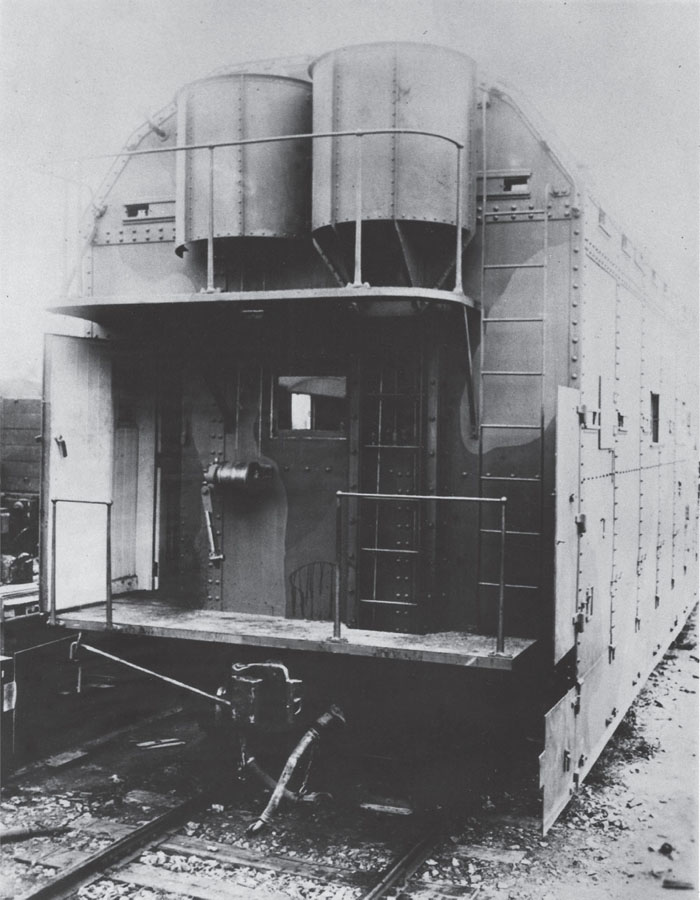

The Command Wagon had two levels, the lower for the radio compartment and the upper for the artillery command post – one can just see the binocular sight projecting from the roof. One of the observation nacelles is in the raised position, as is a radio aerial with its retractable mast passing through the roof. The light armament comprised two MGs and ten rifles.

(Photo: All Rights Reserved)

This view of the Command Wagon shows the two observation nacelles mounted on telescopic tubes. Note the plates protecting the sides of the open platform.

(Photo: All Rights Reserved)

There is no vertical armour over the boiler, but the steam dome is protected from horizontal fire.

(Photo: All Rights Reserved)

A passage ran behind the vertical armour plates on the Manchurian Railways 2-8-0 Type ‘So-ri-i’ tender engine, allowing crew members to pass from one end of the train to the other.

(Photo: All Rights Reserved)

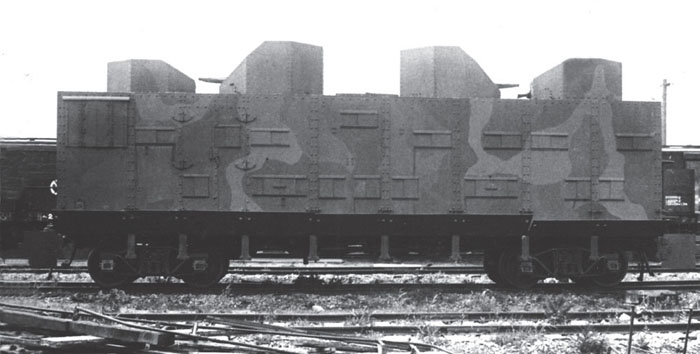

The impressive Auxiliary Tender based on a 50-tonne coal wagon is fitted with two retracting turrets each armed with a 6.5mm Type 11 MG, which allowed observation and fire along the length of the train. Note the central access door.

(Photo: All Rights Reserved)

The Auxiliary Tender carried enough coal for 600km (375 miles) and enough water for 300km (188 miles).

(Photo: All Rights Reserved)

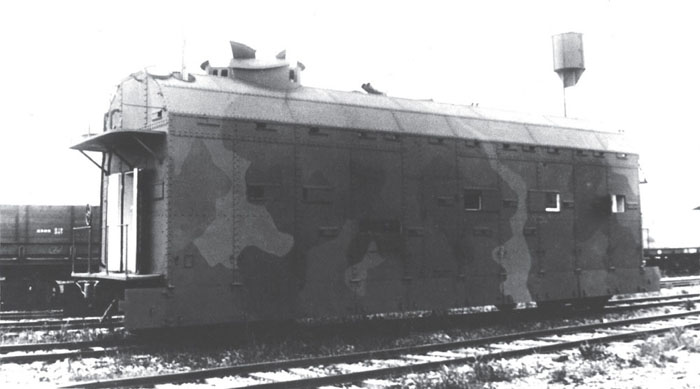

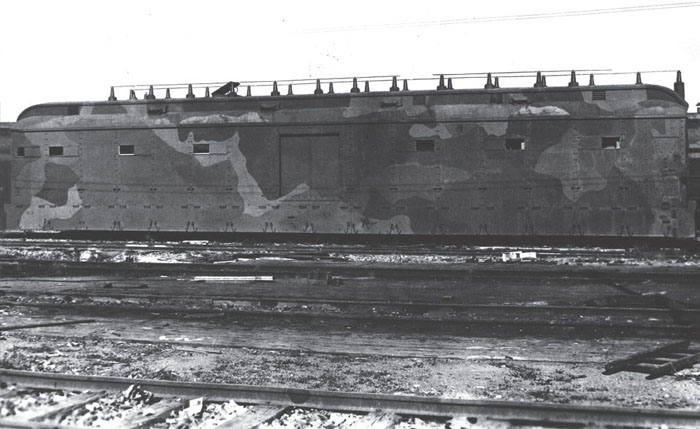

The Technical Equipment Wagon converted from a Type Ha-2 coach. The generator-powered radio equipment required the fitting of frame aerials mounted on insulator blocks.

(Photo: All Rights Reserved)

A fine view of the roof of the Technical Equipment Wagon.

(Photo: All Rights Reserved)

At the rear end of the train was the Howitzer Wagon, based on the same commercial wagons as the other artillery wagons, but with a turret armed with a modified 150mm Type 4 howitzer. The armament also included four Type 3 MGs and ten rifles, for a crew of two officers and twenty men.

(Photo: All Rights Reserved)

The Type 94 Armoured Train was conceived after feedback from operating the previous Temporary Armoured Train. Design began in October 1933 and in one year the train had been built. It would remain a unique example, as there was no follow-up. Although capable of running at up to 65km/h (40mph), it was essentially a coast defence/mobile artillery type of train rather than a track patrol unit. Compared to the other armoured trains used in China and Manchuria, its light armour protection of 6mm and 10mm plates shows that it was not designed for close-range combat.

Its eight elements were as follows, from head to tail:

– Pilot (track control) Wagon.

– Artillery Wagon No 1 (Kó).

– Artillery Wagon No 2 (Otsu).

– Artillery Wagon No 3 (Hei).

– Command Wagon.

– Engine.

– Tender.

– Electrical Generator Wagon.

The Pilot (track control) Wagon at the head of the train, equipped with a 30cm-diameter armoured searchlight. On can see the 7.7mm Type 92 MGs for close-in defence and the sliding shutters for the observation ports. The central coupling knuckle indicates that this wagon has been built on the base of a 30-tonne Type Ta-I mineral wagon.

(Photo: All Rights Reserved)

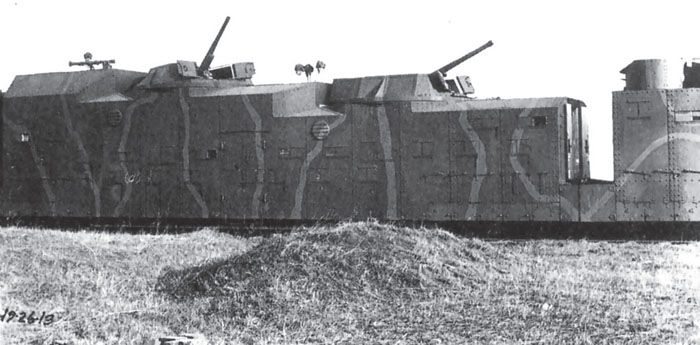

Turrets aligned fore and aft, here the train is photographed between Sakako and Furanten.

(Photo: All Rights Reserved)

A superb view of the complete train, which gives a feeling of invulnerability due to its homogenous design. It underwent running trials from 16 November to 16 December 1934, and in the interim its firing trials on 8 and 9 December.

(Photo: All Rights Reserved)

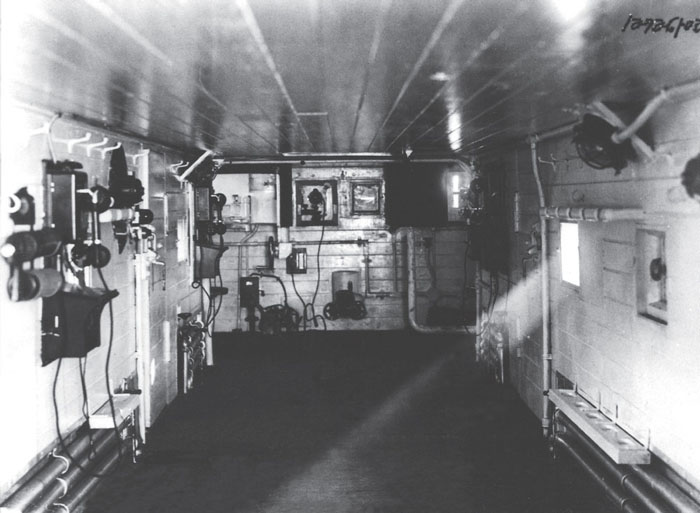

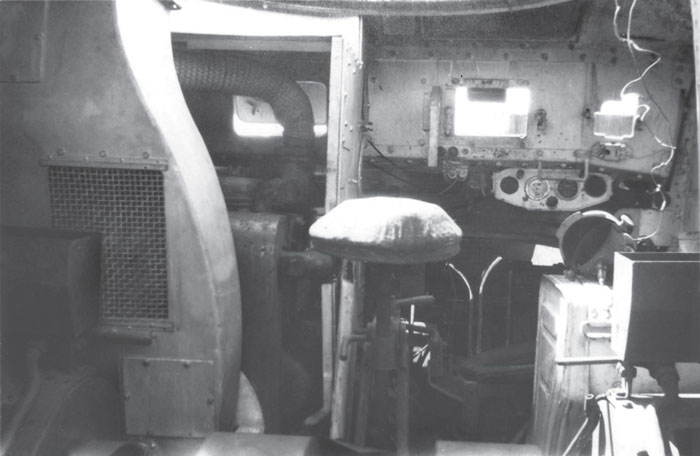

The interior of the Pilot Wagon, which appears to comprise a small command post. Its layout is similar to that of the Command Wagon of the Temporary Armoured Train, and it too carries rails and sleepers mounted on its sides.

(Photo: All Rights Reserved)

The Otsu Wagon was similar in design to the Kó Wagon, except that its super-structure was higher to enable it to fire over the latter. On this wagon all four MG turrets could be used against both ground and air targets. The same as used on board ship, the coincidence rangefinder and its crew are visible on the roof, with the binocular periscope to their left. In the camouflage pattern are yellow or ochre bands intended to break up the regular lines of the wagon.

(Photo: All Rights Reserved)

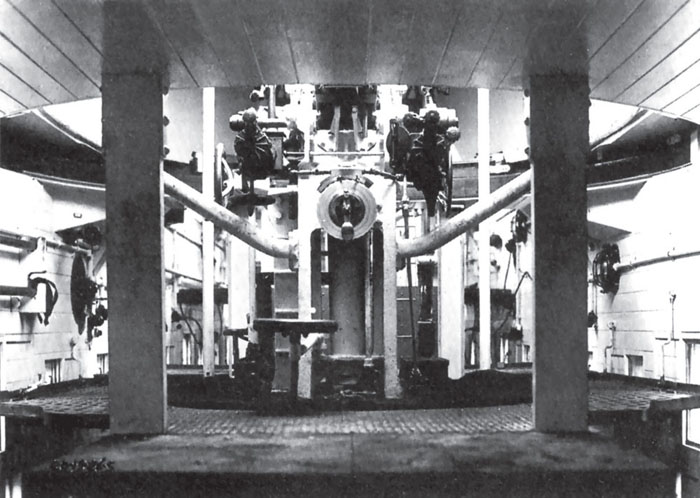

Interior view of the forward part of the Kó Wagon, with its armour plates backed with wood. In the background is the turret revolving basket, while on the left are some of the racks for the 200 shells the wagon carried.

(Photo: All Rights Reserved)

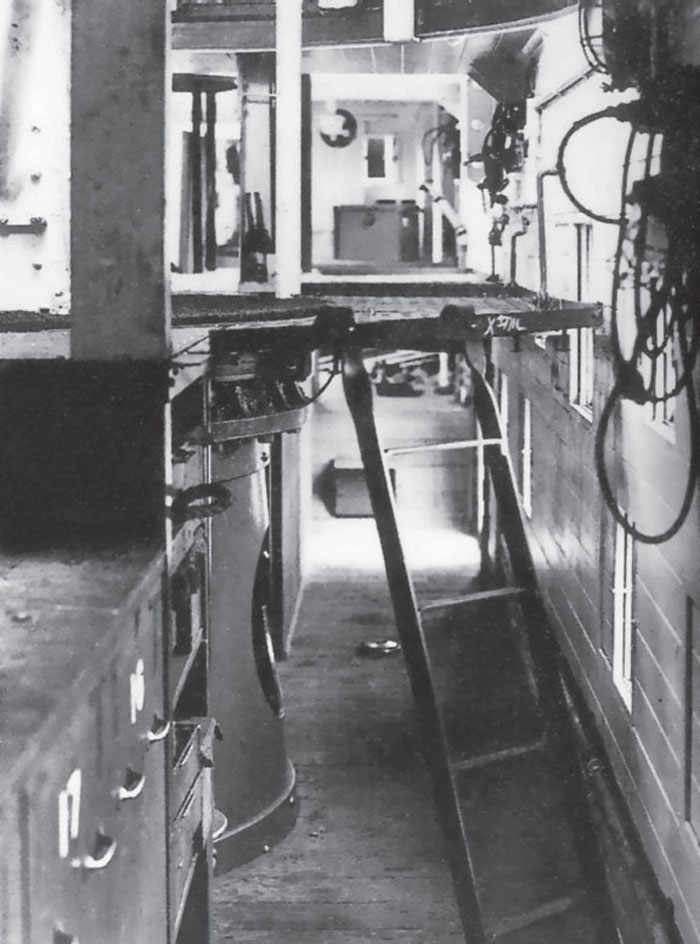

The interior of the Otsu Wagon. The ladder was needed for access to the rotating basket of the turret, set at a higher level than in the Kó version.

(Photo: All Rights Reserved)

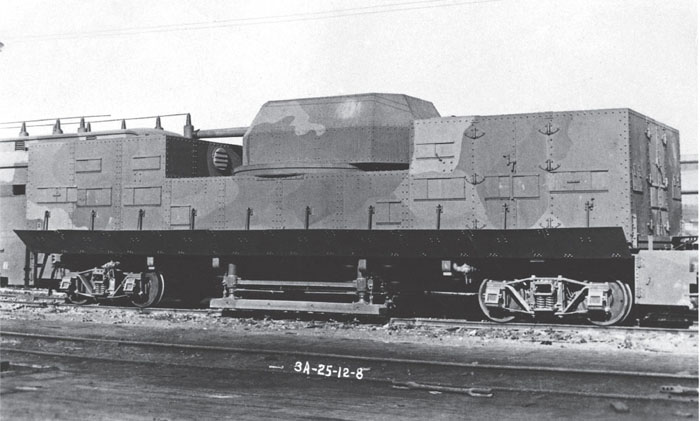

The Kó Wagon is fitted with a single turret armed with a 100mm Type 14 anti-aircraft gun (here used solely against ground targets) with a 270-degree field of fire. Its maximum range was 15km (9.4 miles). The 7.7mm Type 92 MGs in the forward turrets are for use against ground targets, while those in the rear turrets are dual-purpose ground/AA.

(Photo: All Rights Reserved)

As with the other artillery wagons, the Hei Wagon was constructed on the base of a 60-tonne wagon Type Chi-i. The guns are 75mm Type 88 anti-aircraft guns, also capable of engaging ground targets, with a horizontal range of 14km (8.75 miles), provided with 300 rounds each.

(Photo: All Rights Reserved)

This interior view shows one of the turret baskets of Wagon Hei. At the very top of the photo the breech of the 75mm gun is just visible. Although it seems to be a relatively small weapon compared to the size of the wagon, each gun had a rate of fire of some twenty rounds per minute.

(Photo: All Rights Reserved)

The Command Wagon, constructed on the base of a 60-tonne coal wagon Type Ta-sa. Each turret is armed with a 7.7mm Type 92 MG. On can just make out one of the lateral searchlights in its armoured enclosure, plus various optical instruments.

(Photo: All Rights Reserved)

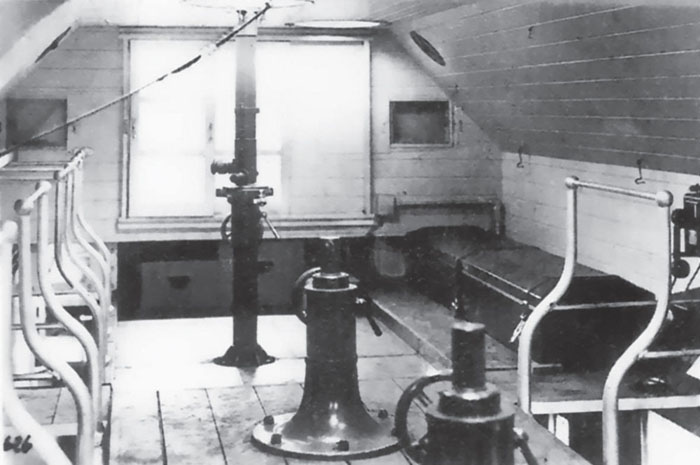

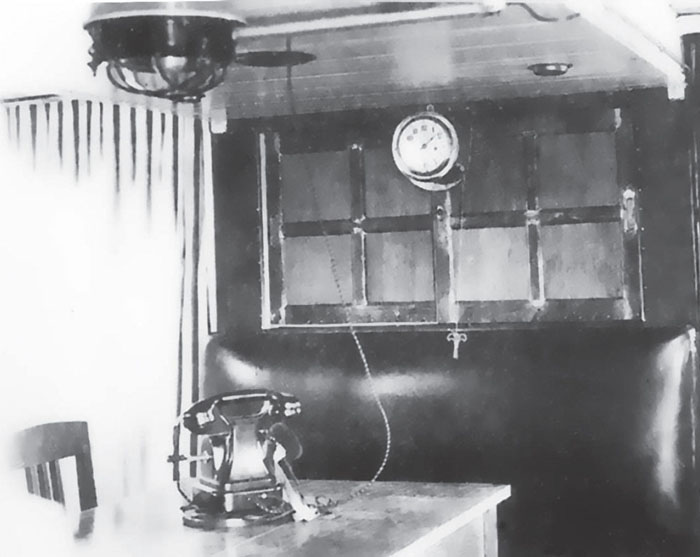

Two views of the interior of the Command Wagon. Above, the upper level with the base of the periscope and various fittings. Below, the lower level, clearly the office for the train command staff.

(Photos: All Rights Reserved)

The Mikado 2-8-2 tender engine has simple vertical armour protection, open at the top.

(Photo: All Rights Reserved)

The smokebox protection is completed by a plate fastened on the front. The cutout enables us to see the American-style smokebox door. The vertical cylinders are perhaps air pumps.

(Photo: All Rights Reserved)

Even the tender was armed: one can just make out the retracting turrets, centre-right and far-left. The water capacity (in the six tanks with circular hatches) and the coal carried sufficed for a range of only 150km (94 miles), showing that the train was never intended for long-distance patrols across the Manchurian plains.

(Photo: All Rights Reserved)

The left-hand side of the tender showing the retractable nacelle in the outboard position, topped by a small rotating turret armed with a 7.7mm Type 92 MG. One can just make out the door at the right-hand end.

(Photo: All Rights Reserved)

A view seldom seen, of the front end of the tender facing the engine, to which it is normally attached by the drawbar clearly visible here. In this photo the MG nacelle is in the retracted, inboard position.

(Photo: All Rights Reserved)

This side view of the Generator Wagon showing its roof-mounted aerial.

(Photo: All Rights Reserved)

End view of the Generator Wagon, bringing up the rear of the train, with its two 7.7mm Type 92 MGs for close-in defence and the armoured 30cm searchlight.

(Photo: All Rights Reserved)

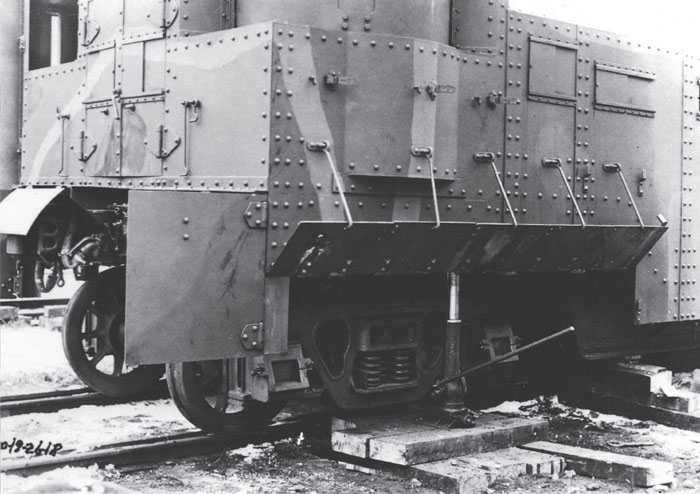

The Kó Wagon having the wheelsets of its bogies changed.

(Photo: All Rights Reserved)

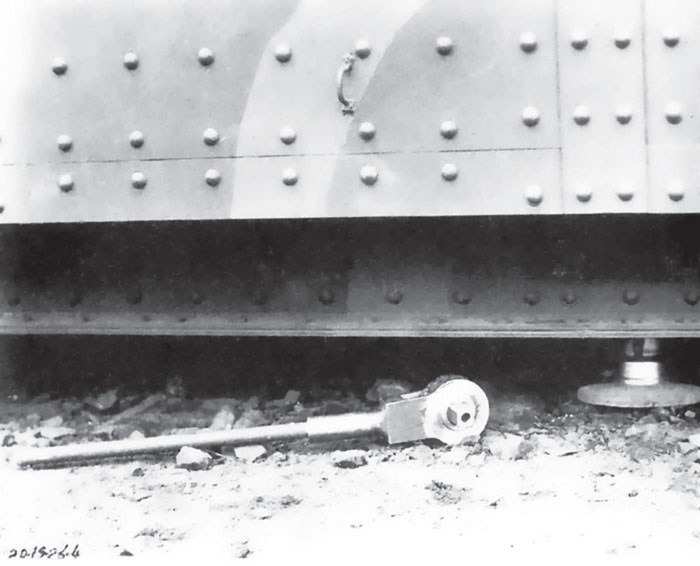

The shoe used to accurately level the artillery wagons for firing.

(Photo: All Rights Reserved)

Two views of a Japanese armoured wagon captured at the end of the Second World War. It is not possible to determine the location, but the presence of a central knuckle coupling plus buffers is indicative of the Russian network.

After the war, Japanese equipment was reused by the various combatants in China and in Korea. This is perhaps one of these armoured trains watched from afar by a group of children, while more adventurous adults scavenge in the wreckage of what appears to have been a head-on collision.

(3 Photos: Paul Malmassari Collection).

It would appear that the Japanese Army authorised only the infantry and cavalry to use armoured vehicles armed with artillery, which would explain why armoured rail trolleys are only seen with machine guns in turrets.

The RSW trolley, based on an armoured truck, was designed in 1929 to carry out railway security missions in Manchuria. The armour was 6mm thick and covered the whole vehicle. Square ports were placed around the four sides of the hull for the personal arms of the crew. The armoured radiator slats could be fixed open to increase the flow of air. For it to run on rails, all that was needed was to remove the solid rubber tyres from the wheel rims. Three headlamps provided the lighting in front of the trolley.

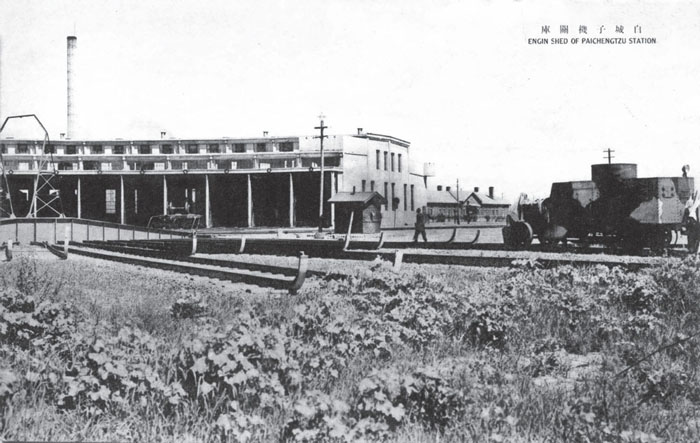

Postcard showing an RSW trolley at the workshops in Paichengtzu in China.

(Postcard: Paul Malmassari Collection)

A view of an RSW Trolley with the crew disembarked. In this vehicle the driver sits on the right-hand side, which explains the larger hatch. The red sun (or ‘Meatball’ as the Americans called it) for air-recognition purposes is painted in the centre of the turret hatch.

(Photo: Paul Malmassari Collection)

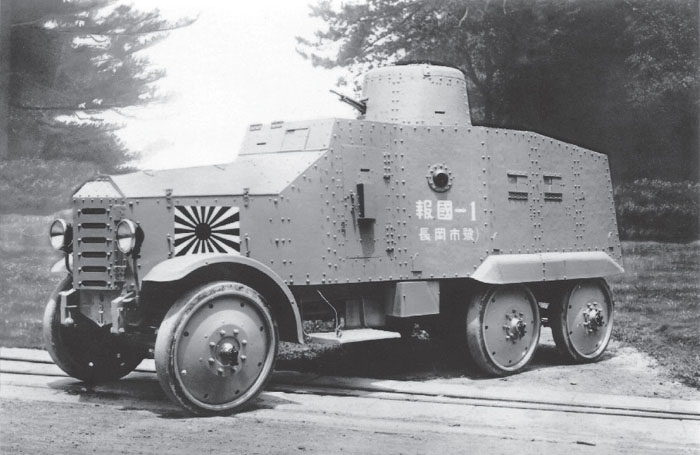

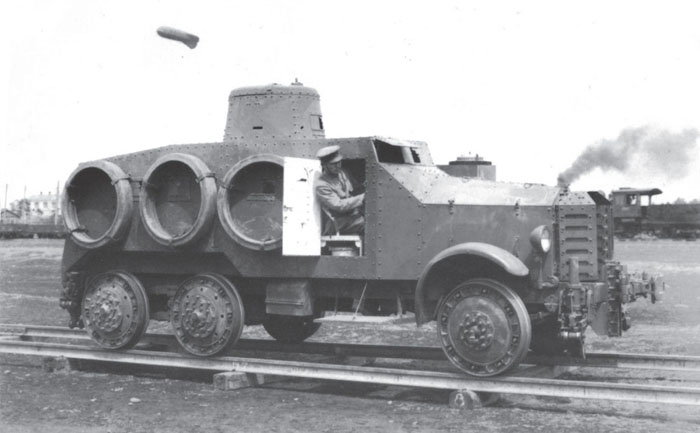

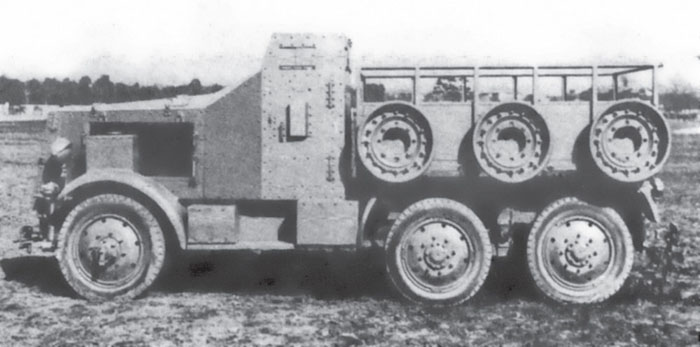

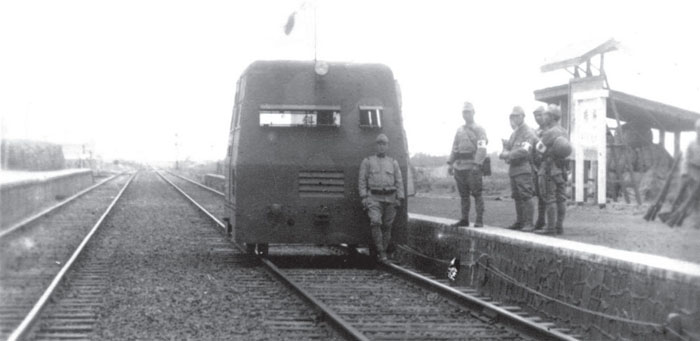

This heavy trolley,13 with the official designation of ‘91-Shiki Koki Kenisha’ or ‘Tractor for Wide Gauge, Type 91’, was identified by Allied wartime intelligence as the Type 93 ‘Sumida’ Armoured Car, an incorrect designation used ever since (and which the author has himself used in previous works).

Built from 1930 onward, this 6x4 vehicle had plain wheels which could be fitted alternatively with solid rubber tyres for the road or with flanged rims for running on rails. Derived from the Naval Type 90 Armoured Car, it weighed 7 tonnes and carried 16mm of armour over its vitals.14

The road-rail conversion took around twenty minutes, and necessitated raising the vehicle by means of the four jacks fitted to the bumpers. In addition, the spacing of the wheels could be adjusted to suit the rail gauge. The trolley reached a maximum speed of 60km/h (38.5mph) on rails as against 40km/h (25mph) on roads. However, as the chassis was unidirectional and lacked a built-in turntable arrangement, it was necessary to couple two trolleys back-to-back to allow for rapid withdrawal under fire. It was armed with six 7.7mm Taisho Type 92 MGs, one of which was mounted in the turret.

Their principal zone of operations was the China and Manchurian theatres, but it seems that several examples were used in Indochina and Malaya. The stated production total of 100 examples could include the Naval Type 90 and the Army Type 91 versions.

The original Navy Type 90, which lacked the means of converting it for rail use. The inscriptions signify ‘Vehicle No 1 offered by the town of Nagaoka’.15

(Photo: Matthew Ecker)

The Army Type 91 on solid rubber tyres for the road, with rail rims and re-railing ramps clamped to the hull sides.

(Photo: All Rights Reserved)

A Type 91 SO-MO of the Tsudanuma Railway Regiment seen in 1939, lacking the brackets for the re-railing ramps.

(Photo: Wawrzyniec Markowski Collection)

A camouflaged version. The re-railing ramp is clearly seen, as is the built-in front railing jack.

(Photo: Heiwa Kinen Tenji Shiryokan)

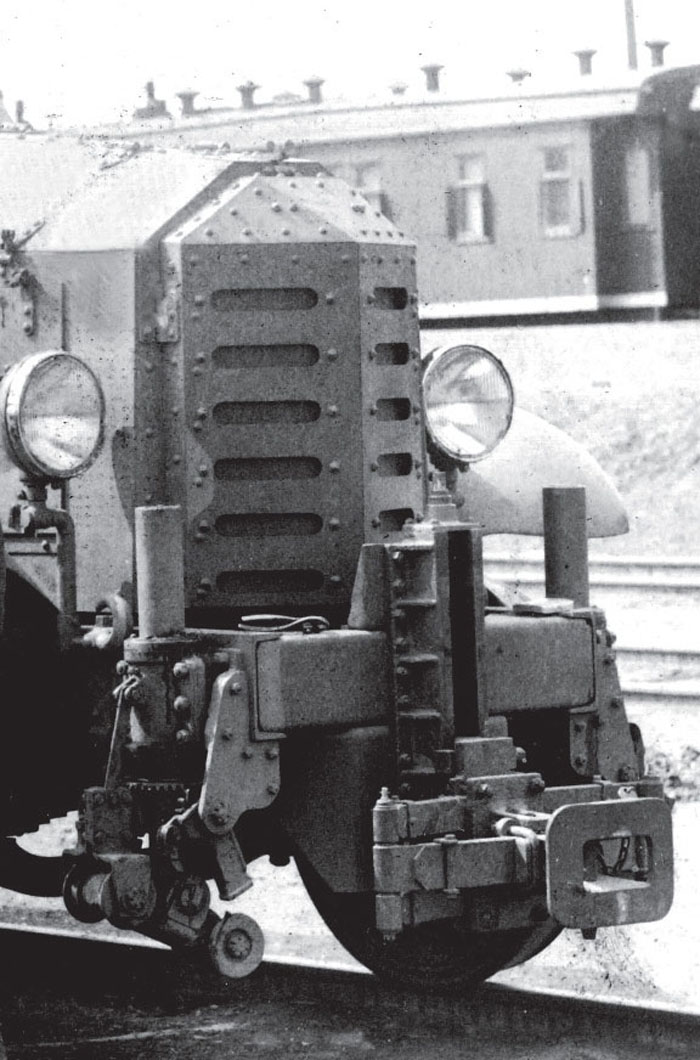

Close-up of the front end detail in the previous view.

(Photo: Heiwa Kinen Tenji Shiryokan)

A well-known view of the front of a SO-MO, showing the central knuckle coupling which was adjustable for height. The four lifting jacks for raising the vehicle above the rails are protected by sacking.

(Photo: Paul Malmassari Collection)

A later configuration, with the front axle replaced by a bogie, easier to repair after hitting a mine, and also providing a better-quality ride over uneven track. The original front wheels are carried on top of the bogie, for reconversion to road use.

(Photo: Wawrzyniec Markowski Collection)

The protection against the cold helps break up the lines of the vehicle and aids in camouflaging it. Note the two boxes (a field modification?) on the cab roof in front of the turret.

(Photo: Wawrzyniec Markowski Collection)

A group photo of SO-MO units with their proud crews, in a summer setting with the armoured flaps of the radiators open. A second photographer is at work capturing the line of four SO-MOs in the background, with one or more wagons coupled in the rake, and behind him is a convoy headed by a road-rail ISUZU truck. This scene demonstrates the wide use the Japanese made of the SO-MO for patrol work. Note the uneven track in the depot, devoid of ballast, laid on closely-spaced wooden sleepers.

(Photo: Heiwa Kinen Tenji Shiryokan)

A fine view of the rear of a trolley, from which one can see that the two rear doors were not symmetrical. The two units are connected in tandem, and this time the armament is in place.

(Photo: Paul Malmassari Collection)

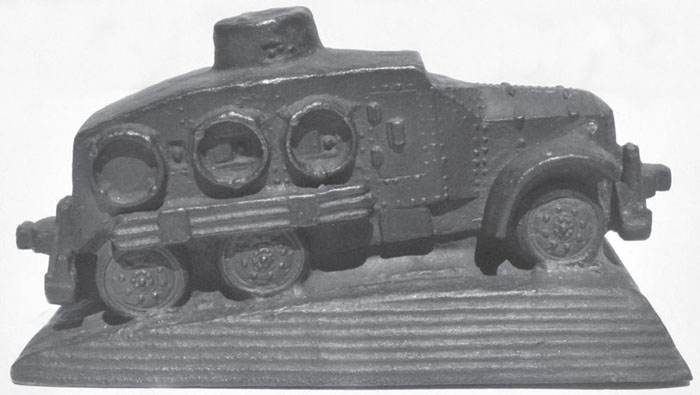

A paperweight in cast iron or white metal, made for the Manchurian Railway Company.

(Private Collection)

Problems on the track near Jehol on 3 September 1933. Troops scan the countryside for any sign of the Chinese who have removed sections of rail.

(Photo: Paul Malmassari Collection)

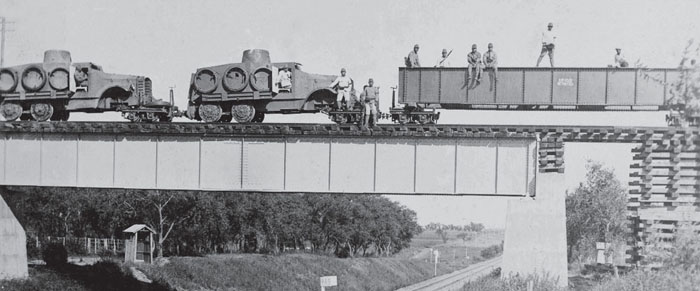

A train crossing a box-girder bridge with no side railings in March 1941. It is possible this is a construction train.

(Photo: Heiwa Kinen Tenji Shiryokan)

The rail-convertible ISUZU truck gave rise to an armoured prototype which closely followed the form of the SO-MO. One difference is that the wheels shod with pneumatic tyres can be replaced by complete flanged rail wheels, and not simply the flanged rims as on the SO-MO.

(Photo: All Rights Reserved)

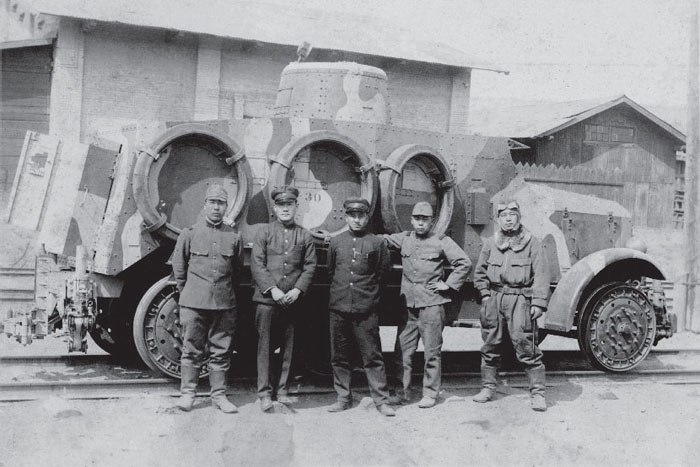

The kind of souvenir photo that every soldier in every army wants, standing with his comrades beside his combat vehicle!

(Photo: HeiwaKinenTenjiShiryokan)

| Length: | 6.57m (21ft 7in) |

| Width: | 1.9m (6ft 3in) |

| Height: | 2.95m (9ft 8in) |

| Speed: | 60km/h (37.5mph) on rails: 40km/h (25mph) on roads |

| Armour: | 6mm min; 16mm max |

| Armament: | 1 x 6.5mm Type 91 machine gun |

| Weight: | 7.7 tonnes |

| Range: | 240km (150 miles) on rails |

| Crew: | 6 |

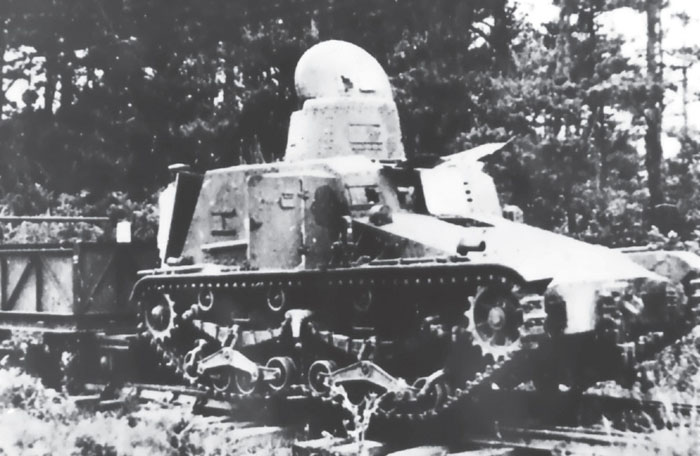

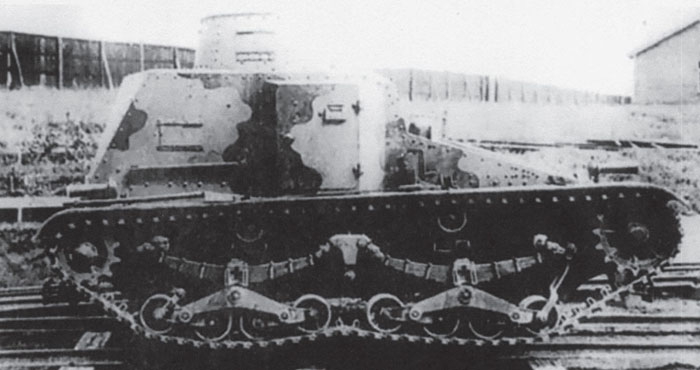

In 1935 the Japanese designed the advanced SO-KI Type 95 Light Tank, of which sixty-five examples were built.16 A number were captured by the Chinese Nationalists,17 then taken over by the Communist forces, and one surviving example is now on display in the Beijing Military Museum. To the best of our knowledge this was the only tracked road-rail armoured vehicle to have seen operational use, in Manchuria and even perhaps in Burma.18

The SO-KI Tank in its ‘rail’ configuration. Its compact dimensions can be gauged by comparison with its crew members beside it.

(Photo: Wawrzyniec Markowski Collection)

Two photos of the SO-KI on display in the Beijing Military Museum.

(Photos: Yichuan Chen)

A fine interior shot of the SO-KI. In the centre is the vehicle commander’s seat, directly beneath the turret.

(Photo: Wawrzyniec Markowski Collection)

The SO-KI could be employed as a rail tractor, as proved by its fittings: hook and tow chains etc.

(Photo: RAC Tank Museum)

When in rail configuration, it was necessary to secure the central part of the track to avoid it rubbing on the sleepers, and to immobilise the outer rollers. The SO-KI could be employed as a rail tractor, as proved by its fittings: hook and tow chains etc.

(Photo: All Rights Reserved)

| Length: | 4.53m (14ft 10¼in) |

| Width: | 2.50m (8ft 2½in) |

| Height: | 2.45m (8ft 0½in) |

| Speed: | 72km/h (45mph) on rails; 80km/h (50mph) on roads |

| Armour: | 6mm min, 8mm max |

| Weight: | 9 tonnes |

| Trench crossing: | 1.50m (4ft 11in) |

| Range: | 355km (222 miles) on rails; 123km (77 miles) on roads |

| Crew: | 6 |

Alongside the armoured trains, a certain number of armoured trolleys of different types were also constructed, some of which we are unable to formally identify. Nevertheless, their interesting designs merit inclusion here. In Manchuria, several radio-controlled trolleys were put into service to act as pilot/safety trolleys in front of the trains. No technical details have come to light.

These unidentified armoured trolleys may be captured Chinese vehicles. The searchlight mounting is similar to the tripod seen in the previous photos of the armoured wagon in Manchuria.

(Photo: Paul Malmassari Collection)

Another unidentified armoured trolley, this time displaying more modern lines.

(Photo: Paul Malmassari Collection)

A well-known type of trolley, of which several examples were built by the Tokyo Gas and Electric Co., here in use as a scout vehicle for a train which is pushing a safety pilot wagon.

(Photo: Wawrzyniec Markowski Collection)

A pair of four-wheeled armoured trolleys, of which the design recalls aspects of the Temporary Armoured Train and the Type 94. The side extensions on the trolley do not have firing ports, only observation windows. The insignia on the officer’s armband is that of the Combat Railways Command.

(Photo: Wawrzyniec Markowski Collection)

The same type of armoured trolley in Chinese service after the war.

(Photo: Wawrzyniec Markowski Collection)

SOURCES:

Books:

Baseilhac, Antoine, Recherches sur l’armée de terre japonaise 1921-1931, Masters dissertation under the guidance of W Serman, Paris I Panthéon-Sorbonne, 1993–4.

Branfill-Cook, Roger, Torpedo, The Complete History of the World’s Most Revolutionary Naval Weapon (Barnsley: Seaforth Publishing, 2014), pp 31–2.

Fujita, Masao, Japanese Armoured Trains (Kojinsha Co., 2013) (in Japanese).

Surlemont, Raymond, Japanese Armour (Brussels: A.S.B.L. Tank Museum V.Z.W., 2010).

Journals and Journal Articles:

Danjou, Pascal, ‘L’automitrailleuse SUMIDA’, Minitracks No 4 (4th Quarter 2002), pp 49–52.

Japanese Tanks up to 1945, Tank Magazine Special Issue (Tokyo: Delta Publishing Co. Ltd., April 1992) (in Japanese).

Lesser-Known Army Ordnance of the Rising Sun (Part 1), Ground Power Special 2005-01 (Cambridge: Galileo Publishing Co. Ltd., 2005) (in Japanese).

Malmassari, Paul, ‘Le Char sur rails Type 95 SO-KI’, TnT No 24 (March 2011), pp 54–5.

Merriam, Ray, and Roland, Paul, ‘Japanese Rail-Riding Vehicles’, Military Journal No 11, pp 12–13.

Panzer No 6 (1996).

Panzer No 9 (1996).

Panzer No 7 (1997).

Panzer Vol 13 No 9 (1990).

Tank Magazine No 2 (1987).

Tank Magazine No 4 (1987).

Tank Magazine No 7 (1987).

The Tank Magazine No 6 (1982).

The Tank Magazine No 7 (1982).

Panzer No 48 (June 1979).

Panzer No 49 (July 1979).

The hull was constructed of plates 6mm and 8mm thick. Note the three headlights at each end to illuminate the track, and the masts holding the radio aerials to receive the control signals. The masts are remarkably similar to those used on the German radio-controlled Fernlenkboot (exploding motorboats) built by Siemens-Schuckert in 1917, perhaps indicating German technical help.

(Photo: Japanese Army Handbook)

1. The 12th Division was the first to land on 3 August 1918 and went into action alongside the Czechs in the region of the Amur and the Ussuri Rivers. At their peak, the Japanese contingent numbered 72,000 men commanded by General Otani, who in theory was nominal head of all the Allied troops. In fact the Russo-Japanese War was still fresh in local memory, and the Russians mistrusted the growing power of Japan.

2. The AEFS, the American Expeditionary Force in Siberia, was withdrawn on 1 April 1920.

3. The Japanese intervention had cost their forces 5,000 dead from combat and disease.

4. Adopted in February 1870. The ‘Hinomaru’ differs from the better-known war ensign adopted in May 1870 which includes sixteen sun’s rays.

5. The Republic of China was created on 1 January 1912 by Sun Yat-sen.

6. The rail network in that region belonged to the Japanese Railway Company of Southern Manchuria.

7. The modern Shenyang.

8. See also ‘Armoured Trains in Comic Books’ in Appendix 1.

9. The island of Formosa had been Japanese since 1895, and only became Chinese again in 1945. We do not know if the defence of the island’s railway network included armoured trains.

10. In Japanese: Soko Ressha.

11. Named after the River Sumida which flows through Tokyo. Originally, the name Sumida was that of the first truck built in 1929 by the Tokyo Ishikawajima Shipbuilding & Engineering Co. Ltd. The name of the workshops is often confused with the name of the SO-MO trolley (see below).

12. The numbering system for Japanese armoured vehicles (and in fact, all weapons) related to the year the Empire was founded, i.e. 660 BC. The year 1931 therefore corresponded to the Japanese year 2091, of which the last two numbers were used, resulting in the designation ‘91’. For weapons introduced from 1941 onward, the ‘zero’ of ‘01’ disappeared and the item became ‘Type 1’.

13. The year designations of four vehicles were close together, as were their characteristics: Types 90 (naval version), 91 (SO-MO Trolley), 92 (Chiyoda Motor Car Factory of the Tokyo Gasu Genki K. K., but also a light tank), which added to the confusion on the Allied side.

14. 16mm on the turret sides and the front face of the hull; 11mm on the hull sides and rear; 6mm on the hull top and floor, and the turret roof.

15. ‘Hokoku-Koto’ was the name of the organisation which offered the vehicles to the Navy, while the corresponding organisation providing vehicles to the Army was the ‘Aikoku-Koto’.

16. Some sources quote a total of 121.

17. A photo was published in the 1 January 1950 edition of El Mundo.

18. Paradoxically, the Japanese SO-KI Type 95 Light Tank ran slightly slower on rails than on roads, but on rails its range was much greater.