The use of various armoured trains by the governments of the day and by certain revolutionary factions make the railways of Mexico one of the lasting symbols of South American revolutions. It is generally held that there were two principal revolutions: that of 1910–12 followed by civil war, and that of 1935–8, and in between the two the War of the Christeros.

Under the dictatorship of General Porfirio Diaz, the development of the railways was a mark of real progress: by 1910 Mexico had 20,000km (c. 12,000 miles) of railway lines, divided basically between two North American Companies, the ‘Ferrocarril Central Mexicano’ and the ‘Nacional Mexicano’. But then the political situation deteriorated and the revolution broke out in November 1910, with the Maderists1 rising up against the government, and the repression which followed. One of the future famous figures of the revolution, Francisco Villa,2 joined the insurgents at the end of November in Chihuahua (North Mexico). In February 1911 Emilio Zapata began his agrarian uprising in Morelos, 80km (50 miles) to the south of the capital. In May, President Diaz resigned and left the country. Madero was elected and crushed the revolutionaries under Zapata who had risen up against him. In February 1913 Madero was assassinated, and was replaced by General Huerta. This saw the beginning of a long troubled period (‘la decena tragica’).

Pancho Villa waged a guerrilla war against the large landowners in Chihuahua. At the head of the División del Norte he captured the major rail junction of Torreón in late September, together with a huge collection of rolling stock. In December 1913 he became Governor of the State of Chihuahua. For his part Zapata continued his guerrilla struggle in the States of Pueblo and Guerrero. In April 1914 the Americans intervened for the first time at Vera Cruz, following the arrest of US sailors and to prevent the landing of a cargo of arms bound for the Federales. To force General Huerta to leave office, the Constitutionalists of Carranza, the troops under Villa (first allies then opponents of Huerta), and those under Zapata converged on Mexico City in a race to see whose forces would enter first. Between April and July 1915, in the struggle between the factions which began after the entry of the Zapatists and the Villaists (on 24 and 28 November 1914 respectively), the railways and the various types of armoured trains played a major role. With some difficulty, the central government progressively regained control of the country.3 The railway system suffered heavily, with bridges demolished, lines torn up or dynamited, and rolling stock destroyed.

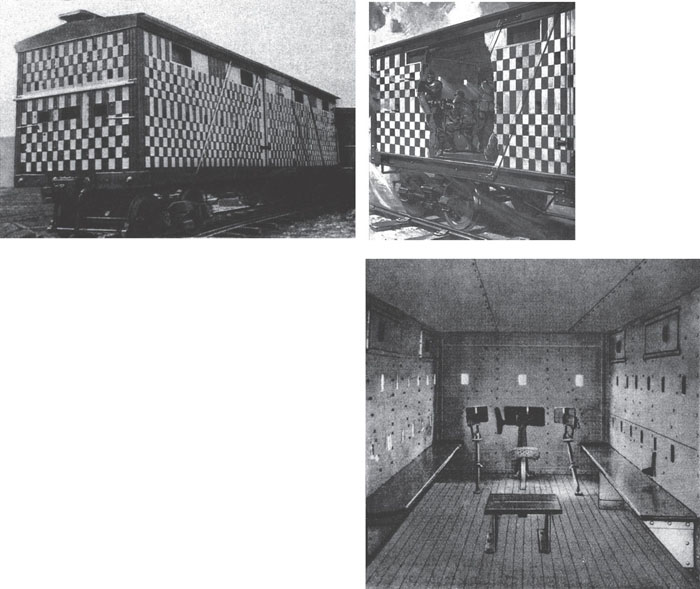

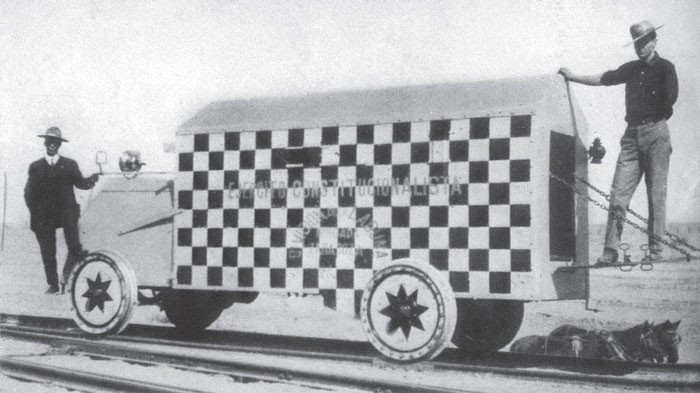

Two photos and a cutaway illustration of the armoured wagon specially camouflaged in a checkerboard pattern, so that at 30m (33 yards) range it was difficult to differentiate between real and dummy firing ports. The interior was sparsely equipped, but allowed the use of rifles at various firing positions. According to the magazine Sciences et Voyages (No 50 12 August 1920, p 337), this wagon could have been built by rebel forces. But another magazine La Nature (No 2053, 28 September 1912), described it as a government wagon, an identification confirmed on the cover of the Illustrated London News of 29 April 1911. This divergence is the proof that one must always verify journalists’ comments, as they may be led astray by their local correspondents.

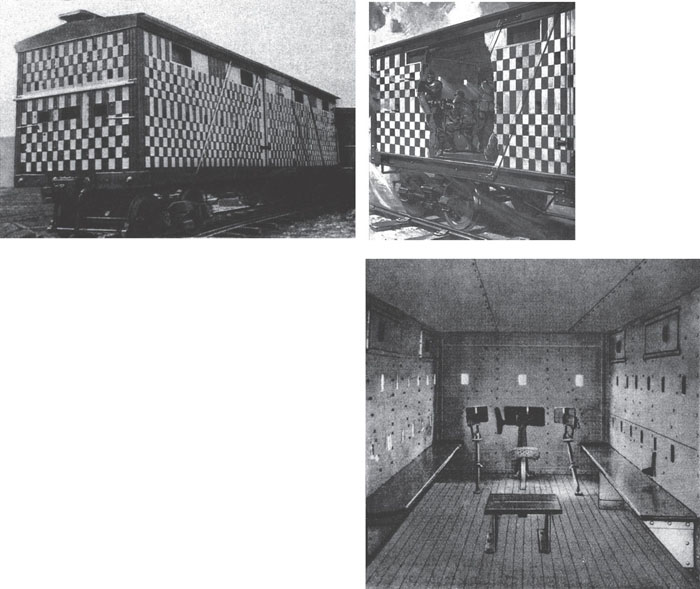

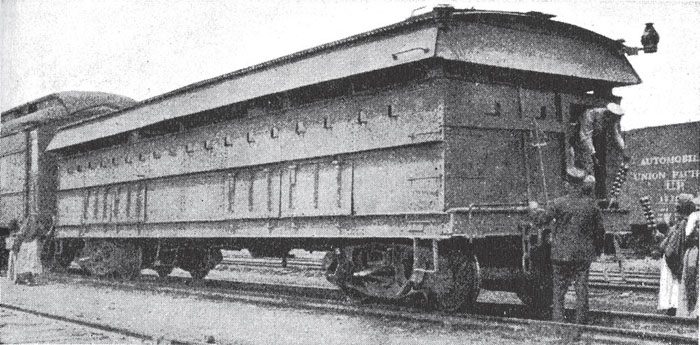

Shown here in 1912 is one of the numerous convoys which attempted to protect the railway. In fact the armoured trains of this period were never used in an offensive role but solely as one component of a means of transport. The protection formed by a wooden wall in the interior of the wagon is clearly visible.

(Photo: All Rights Reserved)

A view of an armoured wagon here photographed during the defence of Chia in 1913. In reality, the field gun would not fire directly over the heads of the infantrymen manning the front casemate, as the muzzle blast would be too dangerous.

(Photo: Philip Jowett Collection)

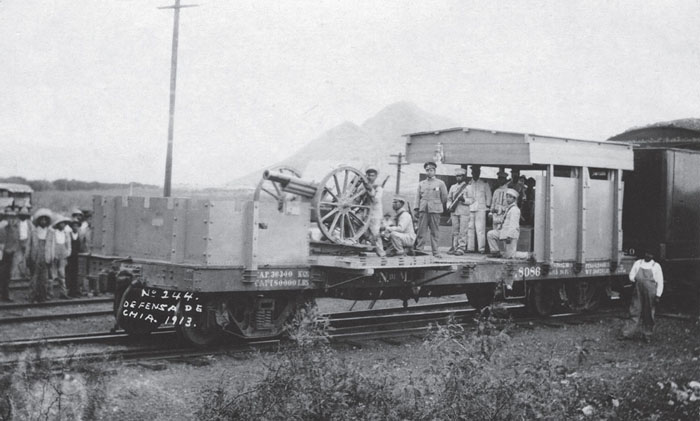

The same wagon as above. The lowered side panels allowed for lateral fire, or they could be hinged upwards to protect the gun and crew.

(Photo: Philip Jowett Collection)

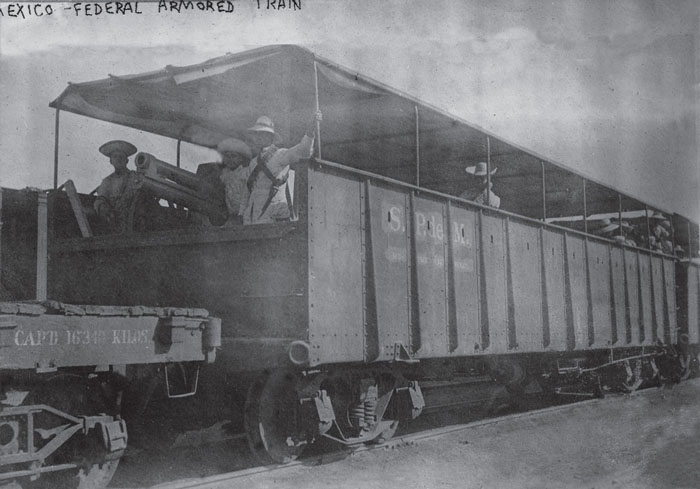

Federal armoured wagon with 80mm Mondragon field gun. That many of these scarce weapons are seen on armoured trains emphasizes their importance.

(Photo: Paul Malmassari Collection)

Built along similar lines to the one shown left, this armoured wagon lacks the firing ports in the front casemate. It appears the gun crew are removing the barrel rearwards, perhaps to change it.

(Photo: Paul Malmassari Collection)

An undated view of a Federal wagon with unique armour protection, armed with a centrally-mounted field gun and machine guns at the four firing ports. The protection appears to be made of wood, and the canopy protects the crew from the sun. The person on the right appears to be an American.

(Photo: Philip Jowett Collection)

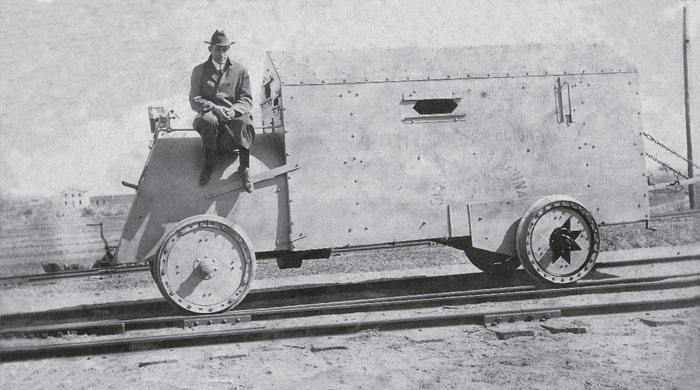

Mack-Saurer trucks, known as ‘Rikers’ from the name of their designer Andrew Riker, were converted to unarmoured rail trolleys to supply the American Expeditionary Force on the Mexican Border in 1916. On the Mexican side, at least one Riker was converted to an armoured trolley for use by the Constitutionalist Army,4 and it appears the armour protection was installed by the North Western Railroad workshops in Juarez.

The Riker on its road wheels. The Constitutionalist Army was created on 4 March 1913 by Venustiano Carranza who established a rebel government in the State of Sonora. This army was divided into divisions, brigades and smaller units, each one bearing the name of a geographical area. Villa was the commander of the Division del Norte.

(Photo: All Rights Reserved)

The same machine again, this time on its rail wheels. The inscriptions in the previous shot are just visible on the hull sides, along with part of the decoration of one wheel. This photo was perhaps taken just prior to it receiving its complete disruptive checkerboard camouflage. Magnification of the photo revealed the name ‘Mack’ on the wheel hubs.

(Photo: Paul Malmassari Collection)

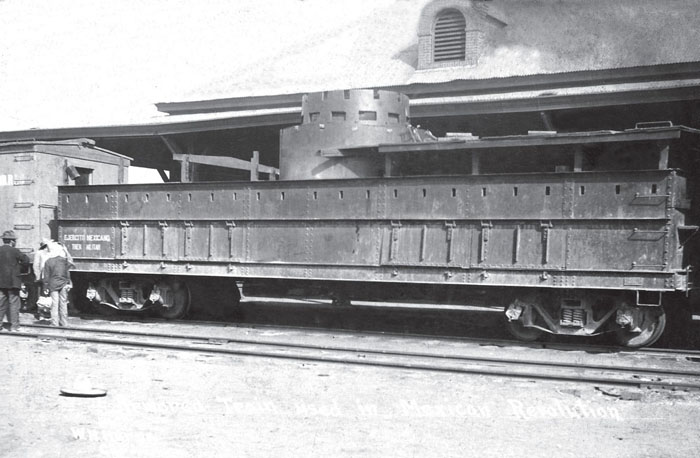

During the Christiade5 (1926–9) the Christeros rose in revolt in thirteen states of Central Mexico. Between March and May 1929, they conquered all of the west of the country (apart from the large towns), and attacked the communications networks. To assure free movement of its troops, the Government ordered the construction of armoured wagons. These units were clearly of much improved design compared with their earlier counterparts.

It only remains to cite the most recent mention of Mexican armoured trains. In the song Adélita by Julien Clerc (1971) we hear the words:

The Mack-Saurer/Riker probably in its final configuration, with the lettering reapplied in a light colour over the (presumably black and white) checkerboard pattern. This is a form of disruptive camouflage – similar to the wagon shown earlier – intended to mask the actual firing points. On the other hand one must express astonishment at the wheel embellishments in the form of stars. Speed on the rails was estimated at 65–70km/h (40 to 45mph) and range as 350km (220 miles).

(Photo: Albert Mroz)

« Elle s’appelait Adélita

C’était l’idole de l’armée de Villa

Pancho Villa

Des trains blindés portaient son nom

Pour son caprice sautaient des ponts

De toute la division du nord

Oui c’était elle le vrai trésor …»

‘She was called Adélita

The idol of the Army of Villa

Pancho Villa

Armoured trains bore her name

At a whim she blew the bridges

Of the whole Northern Division

Oh yes, she was a real treasure …’.

On the other hand the comic book El Tren Blindado only shows an armed train. But the title demonstrates how the image of the armoured train is indelibly stamped on the history of the Mexican Revolutions.

SOURCES:

Heigl, Fritz, Taschenbuch der Tanks (Munich: J. P. Lehmanns Verlag, 1935), Vol II.

Meyer, Jean, La Révolution méxicaine (Paris: Calmann-Lévy, 1973).

Mroz, Albert, American Military Vehicles of World War I (Jefferson [NC] & London, 2009, McFarland & Company, 2009).

Segura, Antonio, El Tren Blindado (Sueca: Aleta Ediciones, 2004).

Near the end of the revolution, the security of travellers was assured by protection wagons inserted in the passenger trains. An American railroad company with connections into Mexico had these armoured wagons built.

(Photo: Le Miroir, No 326 [22 February 1920]).

Taken from Heigl’s famous Taschenbuch der Tanks, this armoured wagon has been constructed on the base of the same type of bogie wagon as in the following shot, and is no doubt one of the wagons General Callès ordered to be inserted in all the trains in 1929.

(Photo: Paul Malmassari Collection)

This photo fits in completely with the notion of the ‘rolling fortress’ all too often applied to armoured trains. But the central structure with its firing ports is remarkable.

The influence of the Russian Revolution and the presence of Trotsky in Mexico inspired the title of this magazine created by Antonio Mella, of the Association of Proletarian Students. Here is Number 1 of September 1928.

1. From the name of Francisco Madero, the founder of the anti re-election party.

2. A well-known bandit, whose real name was José Doroteo Arango Arámbula. Better known by his popular nickname of ‘Pancho Villa’.

3. Zapata was killed on 10 April 1919, Villa laid down his arms in June 1920 and was assassinated in 1923.

4. Ascribed by some sources to Pancho Villa.

5. A rebellion by the Christian Mexicans, against the presidency of General Callès. The rebels opposed the suppression of the Catholic Church, the closure of churches and the arrest of priests.