P.H. Tan |

J.F. Simpson |

G. Tse |

A.M. Hanby |

A. Lee |

|

Fibroepithelial tumours are a heterogeneous group of biphasic neoplasms consisting of a proliferation of both epithelial and stromal components. Fibroadenoma and phyllodes tumours constitute the major entities. Although hamartomas are not strictly fibroepithelial tumours, they resemble neoplasms clinicoradiologically and also have histological similarity to fibroadenomas with incorporation of both stromal and glandular elements; for these reasons they have been included in this chapter.

A common benign biphasic tumour, the fibroadenoma consists of a circumscribed breast neoplasm arising from the terminal-duct lobular unit (TDLU), and featuring a proliferation of both epithelial and stromal elements.

9010/0 |

The fibroadenoma occurs most frequently in women of childbearing age, especially those aged < 30 years, although it may be encountered at any age.

Fibroadenoma typically presents as a painless, solitary, firm, slow-growing, mobile, well-defined nodule of up to 3 cm in diameter. Less frequently, it may occur as multiple nodules arising synchronously or metachronously in the same or in both breasts and may grow very large (up to 20 cm), mainly when it occurs in adolescents. With screening mammography, small impalpable fibroadenomas are being discovered as radiological nodular densities or as calcified lesions. An increased likelihood of developing these lesions has been observed in female transplant recipients treated with cyclosporine for immunosuppression {677}, but changing the immunosuppressant may arrest the progression of cyclosporine-induced fibroadenoma {619}.

Grossly, fibroadenomas are ovoid and well-circumscribed. The cut surface is grey or white, solid, rubbery, bulging, with a slightly lobulated pattern and slit-like spaces. Variations depend on the amount of hyalinization and myxoid change in the stromal component. Calcification of sclerotic lesions is common.

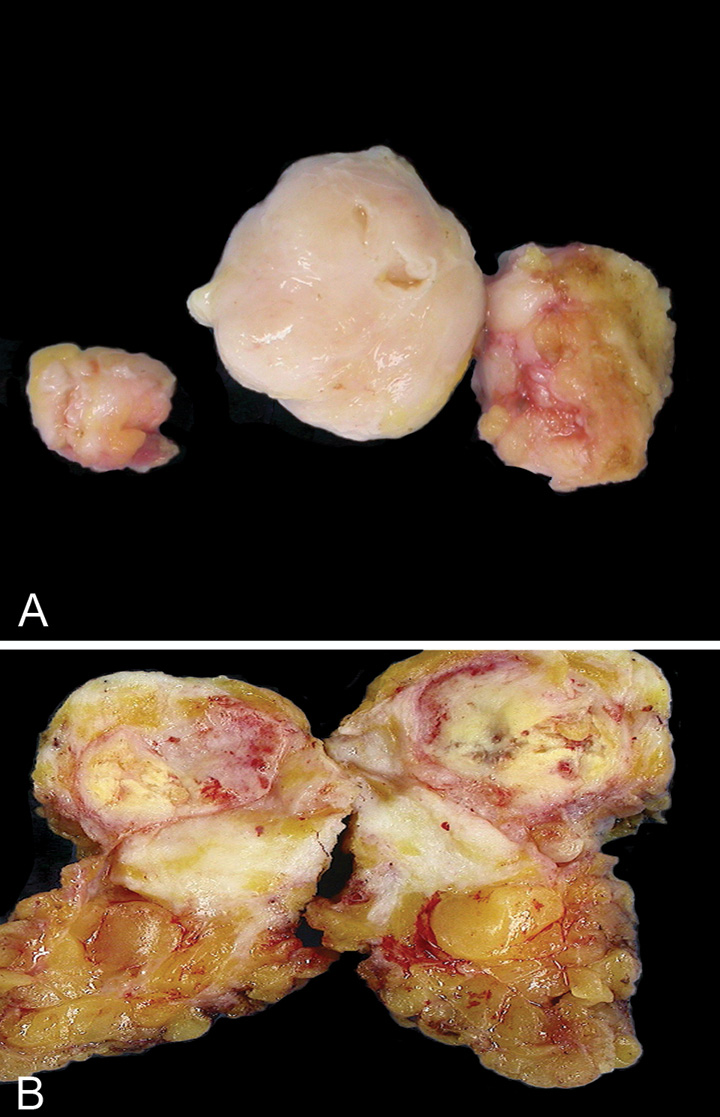

Fig. 11.01 Macroscopic appearance. A Fibroadenoma with lobulated contours and a whitish-grey cut surface. B Ossified fibroadenoma with yellowish gritty areas representing the bony calcified portions. Source: (A,B) Tan P.H.

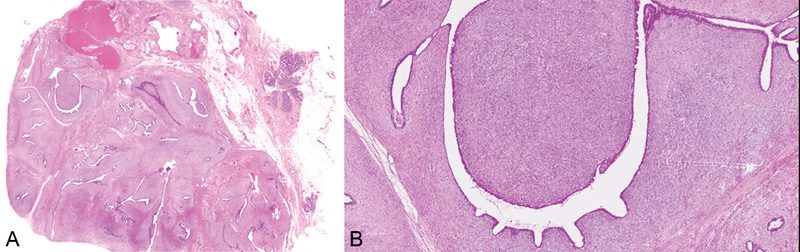

The admixture of stromal and epithelial proliferation gives rise to two distinct growth patterns of no clinical significance. The pericanalicular pattern is the result of proliferation of stromal cells around ducts in a circumferential fashion; this pattern is observed most frequently during the second and third decades of life. The intracanalicular pattern is caused by compression of the ducts into clefts by the proliferating stromal cells. The stromal component may sometimes exhibit focal or diffuse hypercellularity (especially in women aged < 20 years), bizarre multi-nucleated giant cells (which do not have any biological significance), extensive myxoid changes or hyalinization with dystrophic calcification and, rarely, ossification (especially in postmenopausal women). Myxoid fibroadenomas resembling myxomas have been described in association with Carney syndrome {226}. Foci of lipomatous, smooth muscle, and osteochondroid metaplasia may rarely occur. Mitotic figures are uncommon, but may be present, particularly in young or pregnant patients. Total infarction has rarely been reported, although it can occur during pregnancy.

Cellular fibroadenomas, as defined by prominent cellular stroma, may show histological features that overlap with those of benign phyllodes tumour.

The epithelial component of fibroadenoma can show varying degrees of usual ductal hyperplasia, which can be especially prominent in adolescents, and metaplastic changes such as apocrine or squamous metaplasia {730}. Foci of fibrocystic change, sclerosing adenosis and even extensive myoepithelial proliferation can also occur.

“Complex” fibroadenoma contains cysts > 3 mm in size, sclerosing adenosis, epithelial calcifications, or papillary apocrine hyperplasia. It accounts for about 16% to 23% of all fibroadenomas, tending to occur in older patients, with smaller sizes at presentation {358, 1337}. The diagnosis of complex fibroadenoma is reported to be associated with a slightly higher relative risk (3.1 times that of the general population) of subsequent development of breast cancer {358}.

“Juvenile” fibroadenomas occur predominantly in adolescents and are characterized by increased stromal cellularity with a fascicular stromal arrangement, a pericanalicular epithelial growth pattern and usual ductal hyperplasia that often features delicate micropapillary epithelial projections, occasionally described as “gynaecomastoid”-like due to its resemblance to epithelial changes in gynaecomastia. They can sometimes assume enormous sizes, causing breast distortion, and these are referred to by some as “giant” fibroadenomas. However, other authors have restricted the term “giant fibroadenoma” to massive fibroadenomas with usual histology, with sizes often > 5 cm {24,895}.

Atypical ductal or atypical lobular hyperplasia may involve a fibroadenoma, but when confined to the fibroadenoma without involvement of surrounding non-fibroadenoma breast epithelium, the relative risk for subsequent development of breast cancer is apparently not increased {229}. Lobular carcinoma in situ or ductal carcinoma in situ occasionally develops within fibroadenomas. Invasive carcinoma may also affect a fibroadenoma, often as a result of carcinoma in adjacent tissue extending into the fibroadenoma.

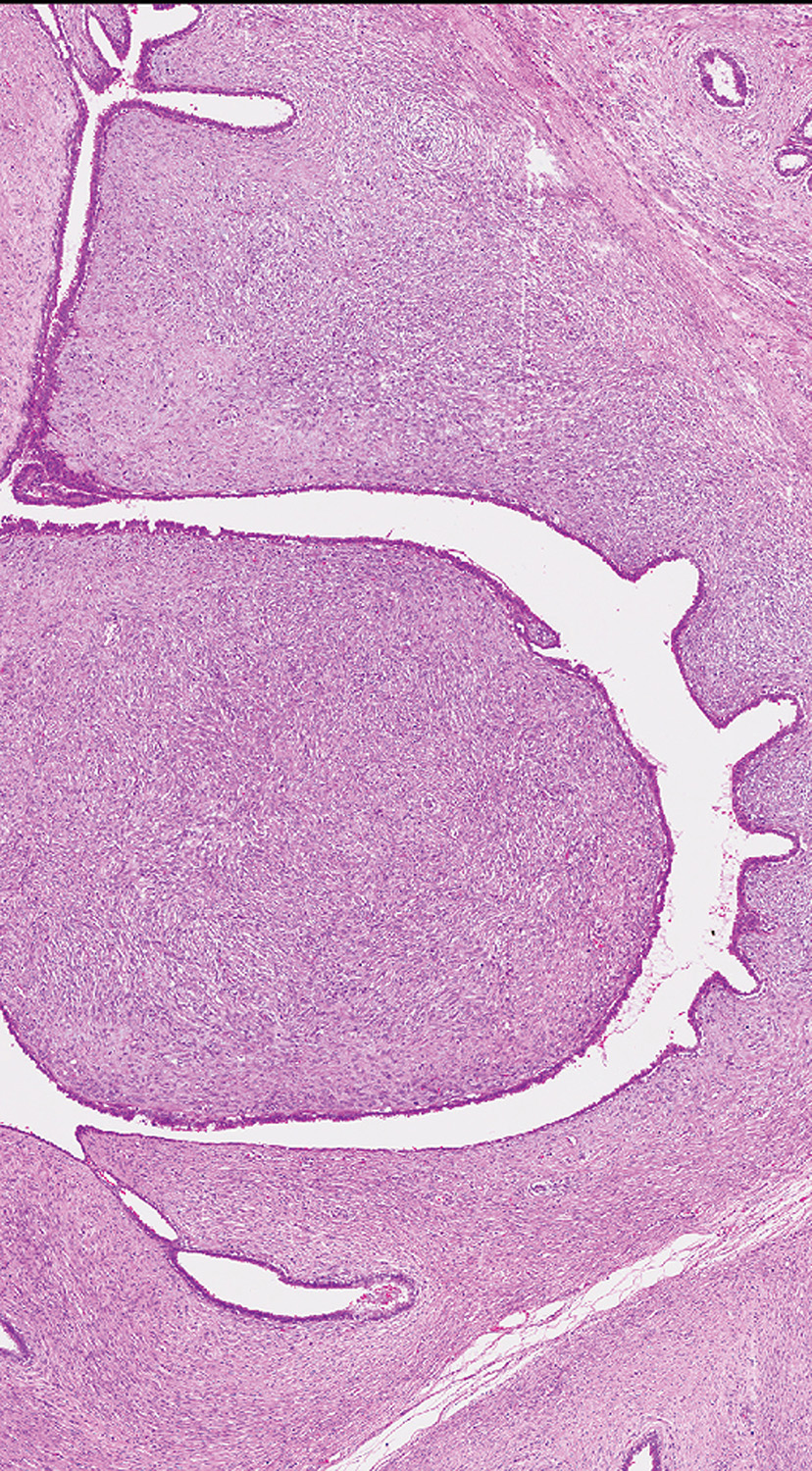

Fig. 11.02 Cellular fibroadenoma shows a pericanalicular growth pattern with a mild and diffuse increase in stromal cellularity. Source: Tan P.H.

Fig. 11.03 Fibroadenoma with intracanalicular growth pattern. Source: Bellocq J.P.

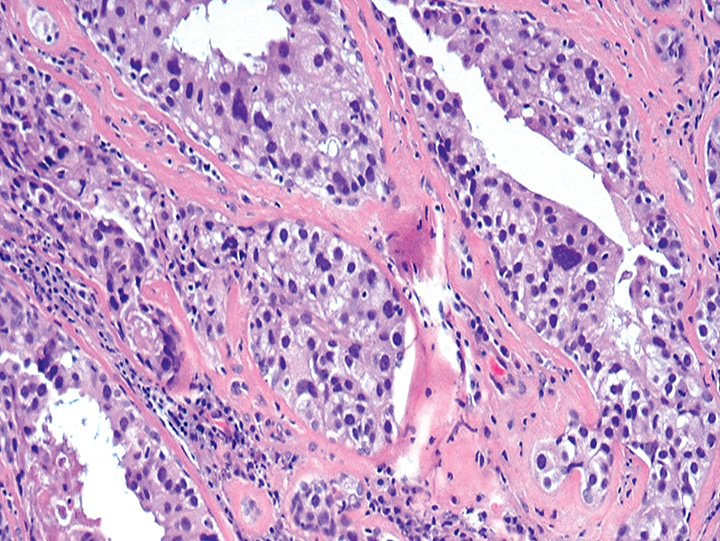

Fig. 11.04 Low-power magnification of a hyalinized fibroadenoma with part of its epithelial component affected by ductal carcinoma in situ. Source: Tan P.H.

Fig. 11.05 Higher magnification of ductal carcinoma in situ, high nuclear grade, within the hyalinized fibroadenoma. Source: Tan P.H.

Intracanalicular fibroadenoma with increased stromal cellularity closely mimics benign phyllodes tumour, with the distinction based on the finding of well-developed fronds resulting from a markedly exaggerated intracanalicular growth pattern accompanied by stromal cellularity, usually diffuse, but sometimes accentuated around epithelial clefts, in the phyllodes tumour. Cellular fibroadenomas and benign phyllodes tumours fall into the same spectrum of benign fibroepithelial lesions, sharing similar histological features, with both possessing a low pot-ential for local recurrence {516,999, 1040,1406}. This differentiation is particularly difficult when considering core biopsies, and if the differential diagnosis includes phyllodes tumour, the lesion would be best classified after excision {632,643,771}.

Numerical abnormalities of chromosomes 16, 18 and 21 with one case of deletion of 17p have been reported in fibroadenomas {102}. Comparative genomic hybridization did not discover any alterations in DNA copy numbers in 20 fibroadenomas analysed {236}. Clonality studies of fibroadenomas found predominant polyclonality of both epithelium and stroma, although monoclonality was observed in areas of stromal expansion, suggesting stromal progression {729}. The DNA of fibroadenomas is less frequently methylated than that of phyllodes tumours {606}.

Most fibroadenomas do not recur after complete surgical excision. In adolescents, there is a tendency for one or more new lesions to develop at another site or even close to the site of the previous surgical treatment. In one study, fibroadenomas without complex features are not associated with an increase in risk of subsequent development of breast cancer, with presence of these complex features being associated with only a slight increase in relative risk {358}.

A group of generally circumscribed fibroepithelial neoplasms, histologically resembling intracanalicular fibroadenomas, characterized by a double-layered epithelial component arranged in clefts surrounded by a hypercellular stromal/ mesenchymal component which in combination elaborate leaf-like structures. Phyllodes tumours (PTs) are classified into benign, borderline and malignant categories on the basis of a combination of histological features, including the degree of stromal hypercellularity, mitoses and cytological atypia, stromal overgrowth and nature of the tumour borders/margins. Most PTs are benign, but recurrences are not uncommon and a relatively small number of patients will develop haematogenous metastases, particularly following a diagnosis of malignant PT. Depending on the bland or overtly sarcomatous characteristics of their stromal component, PTs display a morphological spectrum mimicking cellular fibroadenomas and pure stromal sarcomas.

Phyllodes tumour, not otherwise specified (NOS) |

9020/1 |

Phyllodes tumour, benign |

9020/0 |

Phyllodes tumour, borderline |

9020/1 |

Phyllodes tumour, malignant |

9020/3 |

Periductal stromal tumour, low grade |

9020/3 |

Still widespread in the literature, the generic term “cystosarcoma phyllodes” is currently considered inappropriate and potentially dangerous since most of these tumours follow a benign course and may not display a sarcomatous stroma. It is highly preferable to use the neutral term “phyllodes tumour”, according to the view already expressed in the WHO histological classification of 1981{1599A}, with the prefix of benign, borderline or malignant, as a reflection of putative behaviour based on histological characteristics.

The terms “giant fibroadenoma,” “juvenile fibroadenoma” and “cellular fibroadenoma” have sometimes been used inappropriately as synonyms for benign PT; however, these are distinct entities and ought to be separately classified.

In “Western” countries, PTs account for 0.3–1% of all primary tumours of the breast and for 2.5% of all fibroepithelial tumours of the breast. They occur predominantly in middle-aged women (average age at presentation, 40–50 years) about 15–20 years later than for fibroadenomas. In Asian countries, PTs may occur at a younger age (average age, 25–30 years) {267A}, and account for a higher proportion of primary breast tumours {1404}. Malignant PTs develop on average 2–5 years later than benign PTs. Malignant PT is more frequent among Hispanics, especially those born in Central and South America. Isolated examples of PTs in men have been recorded.

PTs are thought to be derived from intralobular or periductal stroma. They most likely develop de novo, although there have been reports of progression of fibroadenoma to PT {1009}, with rare cases in which the presence of a pre-existing fibroadenoma adjacent to a PT can be demonstrated.

Usually, patients present with a unilateral, firm, painless breast mass, not attached to the skin. Very large tumours (> 10 cm) may stretch the skin with striking distension of superficial veins, but ulceration is very rare. Owing to mammographic screening, tumours of 2–3 cm in diameter are becoming more common, but the average size remains around 4–5 cm. Bloody nipple discharge caused by spontaneous infarction of the tumour has been described. Multifocal or bilateral lesions are rare {1404}.

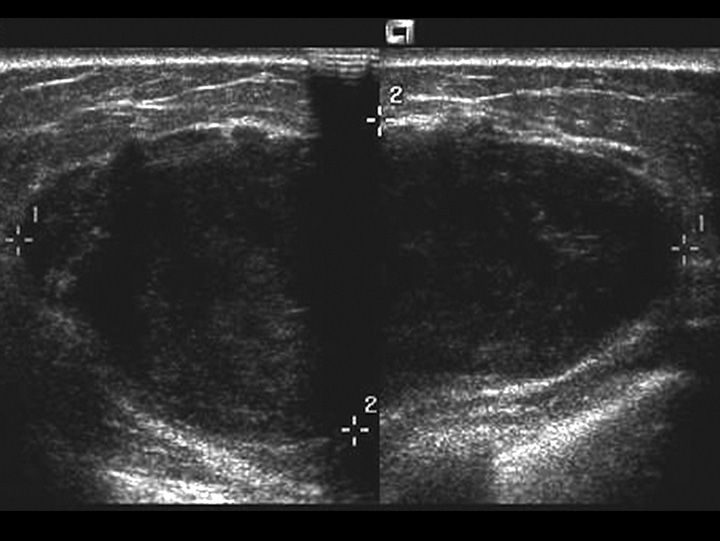

Imaging reveals a rounded, usually sharply defined mass containing clefts or cysts and sometimes coarse calcifications {1401,1608}. Intraductal growth with PT projecting into a cystically dilated large duct has been reported on ultrasound imaging {803}.

Fig. 11.06 Phyllodes tumour. Ultrasonography shows a relatively well-defined hypoechoic mass with macro-lobulations and internal shadows. Source: Tan P.H.

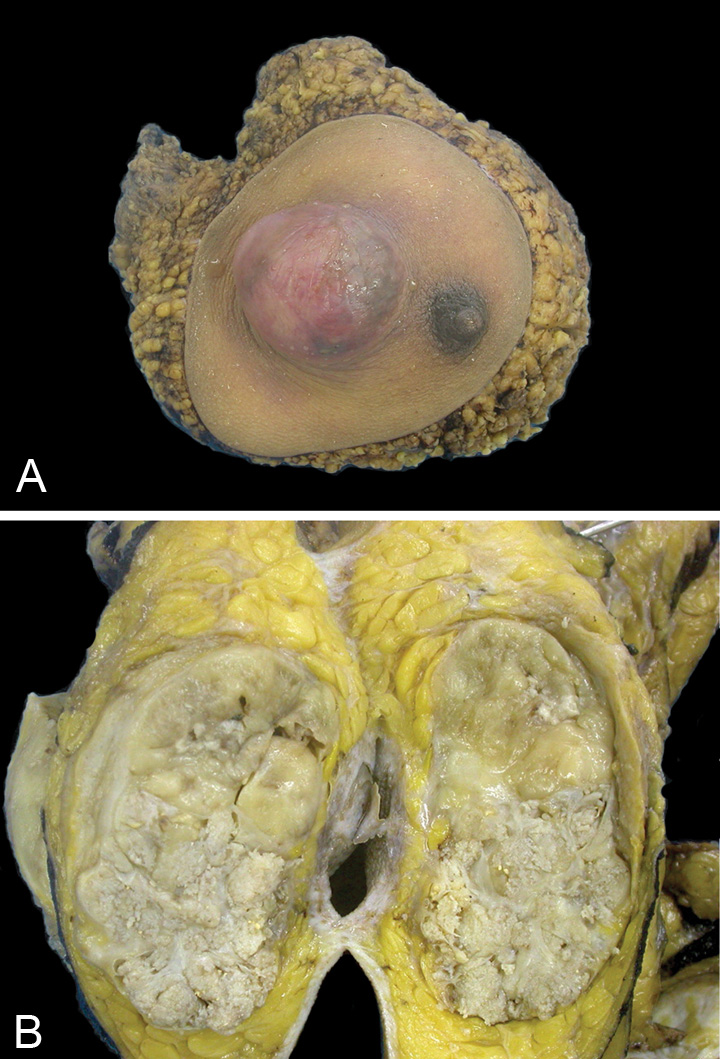

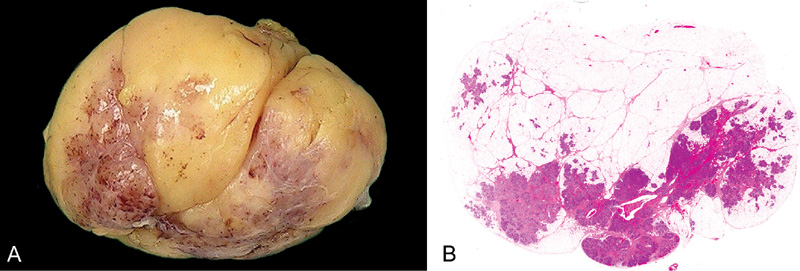

PTs form well-circumscribed firm, bulging masses. Because of their often clearly defined margins, they can be “shelled out” surgically. The cut surface is tan or pink to grey in colour and may be mucoid and fleshy. The characteristic whorled pattern with curved clefts resembling leaf buds is best seen in large lesions, but smaller lesions may have a homogeneous appearance. Haemorrhage or necrosis may be present in large lesions.

Fig. 11.07 Malignant phyllodes tumour. A Right mastectomy with a tumour mass protruding against the skin, located lateral to the nipple. B Cut section through the breast mass reveals a fleshy solid beige-coloured tumour with areas appearing whitish and whorled. Source: (A,B) Tan P.H.

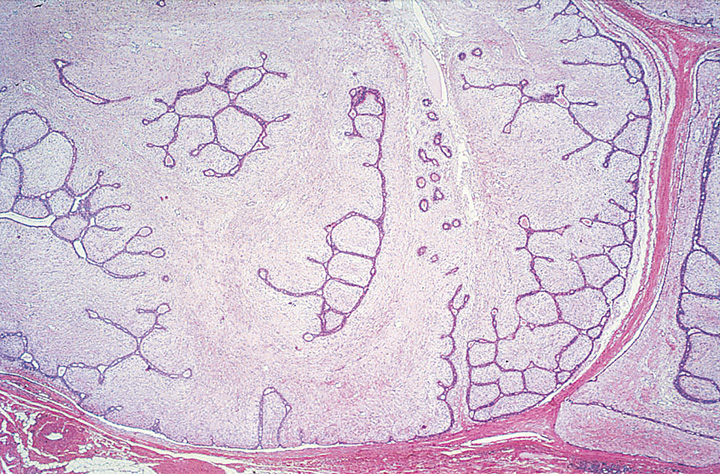

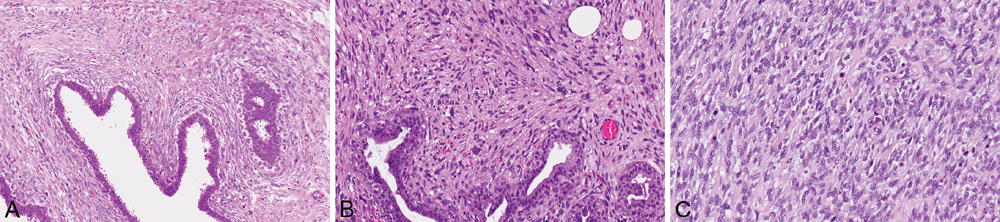

PTs typically exhibit an enhanced intracanalicular growth pattern with leaf-like projections into variably dilated elongated lumina. The epithelial component consists of luminal epithelial and myoepithelial cells stretched into arc-like clefts surmounting stromal fronds. Apocrine or squamous metaplasia is occasionally present and usual ductal hyperplasia is not rare.

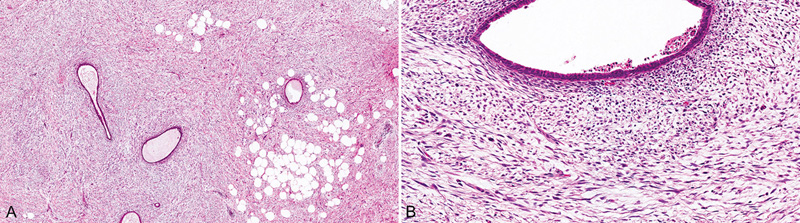

In benign PTs, the stroma is usually more cellular than in fibroadenomas. The spindle-cell stromal nuclei are monomorphic and mitoses are rare, usually < 5 per 10 high-power fields (HPF) {1404}. Stromal cellularity may be higher in the zone immediately adjacent to the epithelium, sometimes referred to as peri-epithelial or subepithelial accentuation of stromal cellularity. Areas of sparse stromal cellularity, hyalinization or myxoid changes are not uncommon, reflecting stromal heterogeneity. Necrotic areas may be seen in very large tumours. The presence of occasional bizarre stromal giant cells should not be taken as a mark of malignancy {616}. Benign lipomatous, cartilagenous and osseous metaplasia have been reported. The margins are usually well-delimited and pushing, although very small tumour buds may protrude into the surrounding tissue. Such protrusive expansions may be left behind after surgical removal and are a source of local recurrence.

Malignant PTs are diagnosed when the tumour shows a combination of marked nuclear pleomorphism of stromal cells, stromal overgrowth defined as absence of epithelial elements in one low-power microscopic field containing only stroma, increased mitoses (≥10 per 10 HPF), increased stromal cellularity which is usually diffuse, and infiltrative borders. Malignant PTs are also diagnosed when malignant heterologous elements are present even in the absence of other features. Owing to overgrowth of sarcomatous components, the epithelial component may only be identified after examining multiple sections with diligent sampling of the tumour.

Borderline PT is diagnosed when the the tumour does not possess all the adverse histological characteristics found in malignant PTs. While borderline PTs have the potential for local recurrence, they usually do not metastasize.

Any PT that has recognizable epithelial elements may harbour ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS), lobular neoplasia, or their invasive counterparts, although this is an uncommon finding. Adequate and extensive sampling of all PTs should be performed as the histological features characteristic of higher-grade tumours may be very focal.

Fig. 11.08 Benign phyllodes tumour. A Low-power magnification demonstrating the characteristic leafy architecture with deep epithelium-lined clefts. B Higher magnification of a leafy stromal frond capped by epithelium. Source: (A-B) Tan P.H.

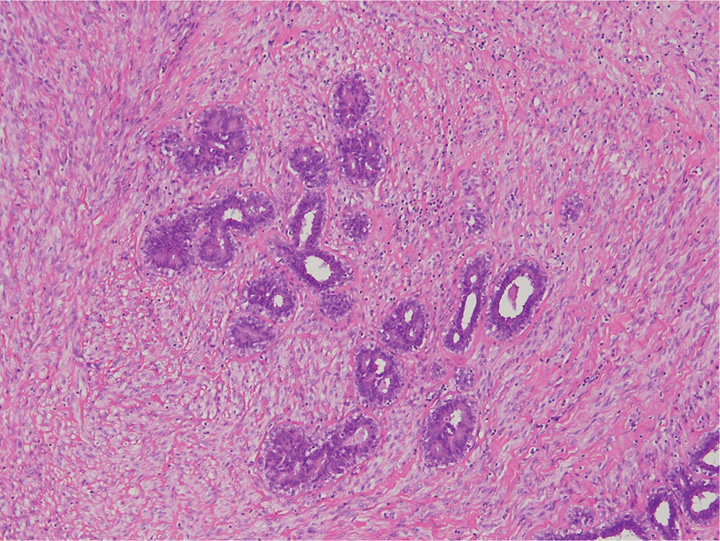

Fig. 11.09 Periductal stromal tumour, low grade. A An infiltrative hypercellular spindle cell proliferation surrounds ducts with open lumina. B At higher magnification, the neoplastic spindle cells contain at least 3 mitotic figures per 10 HPF. Source: (A,B) Tan P.H.

Fig. 11.10 Phyllodes tumour. A Stromal cellularity is accentuated in the peri-epithelial zones of a borderline phyllodes tumour. B Malignant phyllodes tumour shows marked pleomorphism of stromal cells. C Brisk mitotic activity is observed in the stromal cells of a malignant phyllodes tumour. Source: (A-C) Tan P.H.

The main differential diagnosis for benign PT is fibroadenoma having a pronounced intracanalicular growth pattern, and this distinction is sometimes arguably arbitrary and a matter of judgement. A PT should have more cellular stroma along with the formation of leaf-like processes. The degree of stromal hypercellularity that is required to qualify a PT at its lower limit is difficult to define, but the stromal cellularity should be mostly present throughout the lesion, or closely accompanying the leafy fronds, to qualify as benign PT. Increased stromal cellularity adjacent to epithelium, at the epithelial–stromal interface, is often noticed in PT. Leaf-like processes may be found in intracanalicular fibroadenomas with uniformly hypocellular and oedematous stroma, but they are few in number and often poorly formed. The precise distinction between benign PT and fibroadenoma may be problematic in instances, especially in separating a cellular fibroadenoma from a benign PT. As this differentiation may not be significant because of similar clinical outcomes in terms of reported recurrences {516,999,1040,1406}, a diagnosis of fibroadenoma is preferable when there is histological ambiguity, to avoid overtreatment. Some authors advocate using the term “benign fibroepithelial neoplasm”, with explanation of the diagnostic difficulty as needed.

Malignant PTs may be confused with pure sarcomas of the breast. In such cases, diagnosis depends on finding residual epithelial structures. However, the clinical impact of these two entities appears to be similar {1626A}.

Periductal stromal tumour (also referred to by some authors as periductal stromal “sarcoma”, although the neutral term “tumour” is preferred) is an entity that histologically overlaps with PT, the main difference being the absence of leaf-like processes. It is non-circumscribed, consisting of a spindle-cell proliferation localized around open tubules. Progression to classic PT has been documented, suggesting that it may be part of the same spectrum of disease {210}.

Metaplastic carcinoma is also in the differential diagnosis, but immunohistochemical demonstration of epithelial differentiation helps resolve the diagnosis, although caution must be exercised in interpreting very focal keratin expression in limited samples {262B}.

Several grading systems have been proposed, but the use of a three-tiered system, to include benign, borderline, and malignant PT is preferred, because this approach leads to greater certainty at the ends of the spectrum of these fibroepithelial lesions. Grading is based on semi-quantitative assessment of stromal cellularity, cellular pleomorphism, mitotic activity, tumour margin/border appearance and stromal distribution/overgrowth.

The histological features used to distinguish benign, borderline, and malignant PT should be considered together, because emphasizing an individual feature may result in over-diagnosis, especially in the case of mitotic activity. Because of the structural variability of PTs, the selection of one block for every 1 cm of maximal tumour dimension is appropriate. Moreover, because the interface with normal breast tissue is critically important, histological examination of this area is essential. In rare examples, adjacent fibroadenomatoid change or periductal stromal hyperplasia can be difficult to distinguish from the infiltrative border of a phyllodes tumour. PTs should be graded according to the areas of highest stromal cellular activity and most florid architectural pattern. Since the size of HPFs is variable among different microscope brands, it has been suggested that the mitotic count be related to the size of the field diameter (×40 objective and ×10 eyepiece, 0.196 mm2). Stromal overgrowth has been defined as stromal proliferation to the point where epithelial elements are absent in at least one low-power field (×4 objective and ×10 eyepiece, 22.9 mm2) {1404}. Several biological markers, including p53, Ki67, CD117, EGFR, VEGF, microvessel density {1405, 1461,1462,1462A}, p16, pRb and HOXB13 {267, 679A}, among others, have been reported to show increasing expression with PT grade, although these molecular markers have not as yet been proven to be of clinical utility.

As the histological features of PTs fall within a continuum, some of these lesions are difficult to grade precisely. Since malignant PTs are those most likely to cause metastasis and death, it is important to identify this group. So-defined, one study revealed that malignant PTs are associated with a metastatic and death rate of 22%, while no distant metastases were seen in borderline and benign PTs over the same duration of follow-up {1406}. Strict histological criteria for diagnosing malignant PT should be used in order to avoid overtreatment.

Table 11.01 Histological features of fibroadenoma, benign, borderline and malignant phyllodes tumours

|

|

Phyllodes tumour |

||

Histological feature |

Fibroadenoma |

Benign |

Borderline |

Malignanta |

Tumour border |

Well-defined |

Well-defined |

Well-defined, may be focally permeative |

Permeative |

Stromal cellularity |

Variable, scanty to uncommonly cellular, usually uniform |

Cellular, usually mild, may be non-uniform or diffuse |

Cellular, usually moderate, may be non-uniform or diffuse |

Cellular, usually marked and diffuse |

Stromal atypia |

None |

Mild or none |

Mild or moderate |

Marked |

Mitotic activity |

Usually none, rarely low |

Usually few |

Usually frequent |

Usually abundant |

Stromal overgrowth |

Absent |

Absent |

Absent, or very focal |

Often present |

Malignant heterologous elements |

Absent |

Absent |

Absent |

May be present |

Distribution relative to all breast tumours |

Common |

Uncommon |

Rare |

Rare |

Relative proportion of all phyllodes tumours |

— |

60–75% |

15–20% |

10–20% |

HPF, high-power fields. a While these features are often observed in combination, they may not always be present simultaneously. Presence of a malignant heterologous element qualifies designation as a malignant phyllodes tumour, without requirement for other histological criteria. |

||||

Benign and borderline PTs are a paradigm of epithelial–stromal cross-talk, with the epithelium influencing stromal growth, e.g. via the Wnt signalling pathway, upregulation of transcriptionally active beta-catenin and downstream effectors such as cyclin D1 {644,656,657,1270}. The stroma in turn is able to influence the epithelium, e.g. via IGF and IGFR1 {656}. Evidence for loss of this feedback mechanism is given by loss of nuclear beta-catenin in many malignant PTs, some of which show heterogeneous, extensive cytogenetic abnormalities including amplification of MYC and aberrant expression of TP53 {1271,1405}.

Other described cytogenetic changes include gains in chromosome 1q and losses at chromosome 13, reported to be associated with malignant progression {741}, with an increasing number of chromosomal abnormalities with increasing tumour grade {50}. Preliminary data from array comparative genomic hybridization (CGH) demonstrate interstitial deletion of 9p21 involving the CDKN2A locus and 9p deletion in malignant and some borderline PTs {657}.

Most PTs behave in a benign fashion, with local recurrences occurring in a small proportion of cases. Very rarely (about 2% or less overall), the tumour may metastasize, mainly in the cases of tumours of malignant grade.

Local recurrences can occur in all PTs, at an overall rate of 21%, with ranges of 10–17%, 14–25% and 23–30% for benign, borderline and malignant PTs, respectively. These recurrences may mirror the microscopic pattern of the original tumour or show dedifferentiation with microscopic upgrading (in 25–75% of cases) {1400,1406}.

Many histological features have been reported to possess predictive value for local recurrences in PT, and status of surgical margins at previous excision appears to be the most reliable. Other less consistent predictors include stromal overgrowth, classification/grade and necrosis {106,1404}. A recent study found that, apart from surgical margins, histological parameters that had an independent impact on recurrence were stromal overgrowth and atypia, with mitotic activity being almost significant {1406}.

Distant metastases, seen almost exclusively in malignant PTs, have been reported in nearly all internal organs, but the lungs and skeleton are the most common sites of spread {1289,1406}. Most metastases consist of stromal elements only. Axillary lymph-node metastases are rare, but have been recorded {434,551}.

Local recurrences generally develop within 2–3 years, while most deaths from tumour occur within 5–8 years of diagnosis {76A, 324A}, sometimes after mediastinal compression through direct chest-wall invasion.

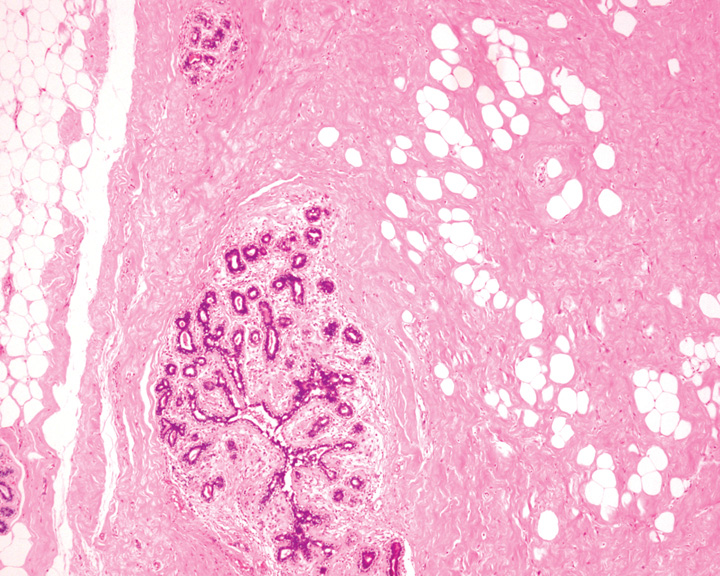

A well-demarcated, generally encapsulated mass composed of all breast-tissue components.

Hamartomas comprise 4.8% of benign breast tumours {247}. These lesions occur predominantly in women in their 40s, but may be found at any age, from teenagers to women in their 80s.

Hamartoma may present as a soft palpable mass {569,1460} or be asymptomatic and detected by mammography {319, 1538}. Imaging shows a circumscribed rounded mass, sometimes with intralesional heterogeneous echogenicity on ultrasonography {145}.

Owing to their well-defined borders, hamartomas are easily enucleated.

Hamartomas are round or oval, measuring up to 20 cm in diameter. The cut surface may resemble normal breast tissue, lipomas or fibroadenomas.

Generally encapsulated, hamartomas are lobulated and show ducts, lobules with interlobular fibrous tissue and adipose tissue in varying proportions. Pseudoangiomatous stromal hyperplasia and smooth muscle may be present {247, 443, 1460}. Both the epithelial and stromal components may express hormone receptors {569}. Differentiation of hamartomas from fibroadenomas may be difficult on needle biopsy and is often impossible on fine-needle aspiration {570, 1460}. The adenolipoma is considered a hamartoma as it incorporates normal breast ducts and lobules within adipose tissue {662A}.

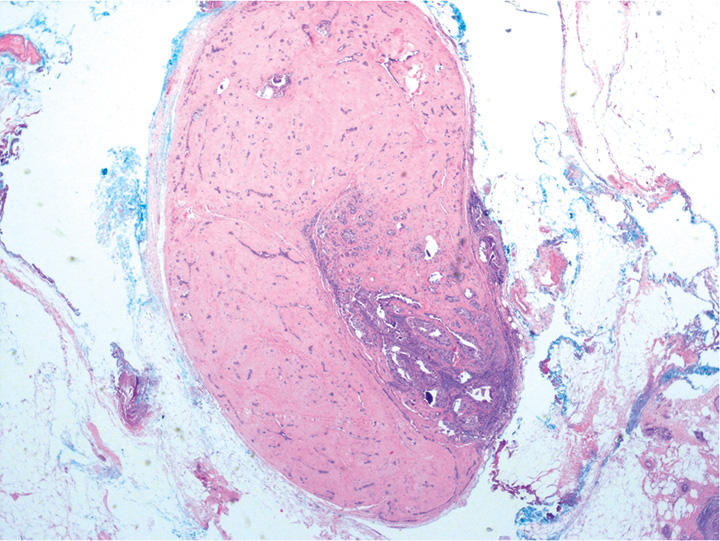

Fig. 11.11 A hamartoma showing a rounded border, inter-lobular fibrosis and a fibroadipose stroma. Source: Tan P.H.

Fig. 11.12 Adenolipoma. A Macroscopic appearance of adenolipoma shows a well circumscribed, slightly lobulated fatty tumour with fibrous areas. B Histology shows mature adipose tissue with admixed breast lobules. Source: (A,B) Tan P.H.

Hamartomas can be seen in Cowden syndrome {1286}. Genetic data are limited, but aberrations involving chromosomal regions 12q12–15 and 6p21 have been described {306,1197}.

Hamartoma is benign and recurs rarely {1460}.