A. Reiner |

|

S. Badve |

|

Gynaecomastia is a non-neoplastic, often reversible enlargement of the male breast associated with proliferation of ductal elements and mesenchymal components.

No other terms are used widely today.

Gynaecomastia is a relatively common condition, occurring at any age, although it shows a bimodal age distribution with peaks during puberty and the sixth and seventh decades of life. Transient breast enlargement in male infants, attributable to exposure to maternal hormones, can be seen, but this usually regresses spontaneously within a few weeks. Similarly, an incidence of reversible breast enlargement of 50–70% in adolescent boys has been reported {963}. In adulthood, palpable breast tissue occurs in 30–65% of males, with autopsy studies documenting a frequency of up to 55% {44}.

Gynaecomastia presents as a palpable tender mass beneath the areola. It may be bilateral or unilateral. In cases of bilateral involvement, enlargement may predominate on one side. Clinical examination includes assessment of endocrine status and possibly imaging technology {655}. Etiological factors are listed in Table 15.01. Patient history, particularly a detailed history of drug intake, may provide a clue to the etiology of disease.

Table 15.01 Etiological factors involved in the pathogenesis of gynaecomastia

Hormonal imbalance |

Causea |

Absolute excess of estrogens |

Therapeutic administration (e.g. prostate cancer) |

Increased endogenous production of estrogen |

Tumours (e.g. Leydig cell tumour, feminizing adreno-cortical tumours) Increased aromatization of androgens to estrogens (e.g. obesity, ageing, alcoholic liver cirrhosis, hyperthyroidism) |

Absolute deficiency of androgens |

Hypogonadism (e.g. Klinefelter syndrome, testicular trauma, mumps, orchitis, drugs) |

Altered ratio of serum androgen to estrogen |

Puberty |

Decreased androgen action |

Drugs |

a Examples are given in parentheses and do not list causes completely. For a review see {963} |

|

The gross appearance is generally not specific but differs significantly from that seen in breast carcinoma. The lesion consists of an either circumscribed or ill-defined greyish-white, firm tissue that merges with the adjacent fatty tissue.

The histological appearance varies according to the relative proportion of ducts and mesenchymal tissue. The ducts, increased in number, are lined by a bilayer of epithelial and myoepithelial cells and are surrounded by fibrous stroma admixed with adipose tissue.

Two main histological patterns are described that may co-exist in a given lesion. The florid pattern is characterized by irregular branching ducts that show proliferation of epithelial cells. These cells may be organized in small focal tufts and exhibit a micropapillary growth pattern. Proliferation is usually mild but can be prominent and mitotic figures may be visible. However, cellular anaplasia is not seen. The surrounding stroma is loose, oedematous, often cellular (fibroblastic) and composed of fibroblasts and myofibroblasts. The fibrous pattern is characterized by hyalinized, sparsely cellular periductal stroma and flat bilayered epithelial lining of the ducts. The architecture can be similar to that seen in pseudoangiomatous stromal hyperplasia {89}. In rare cases, apocrine or even squamous metaplasia may be observed. Atypical ductal hyperplasia is an extremely rare event but has been described {1414}. Benign but atypical multi-nucleated stromal cells similar to those described in the fem-ale breast can be occasionally identified {89}. Lobules are very rare in the normal male breast but can be seen; their presence has been associated with hormonal co-stimulation by estrogens and progesterone. No relationship between histological type and cause of gynaecomastia exists.

True gynaecomastia should be distinguished from pseudo-gynaecomastia, which consists of adipose tissue only, and from the rare cases of breast carcinoma.

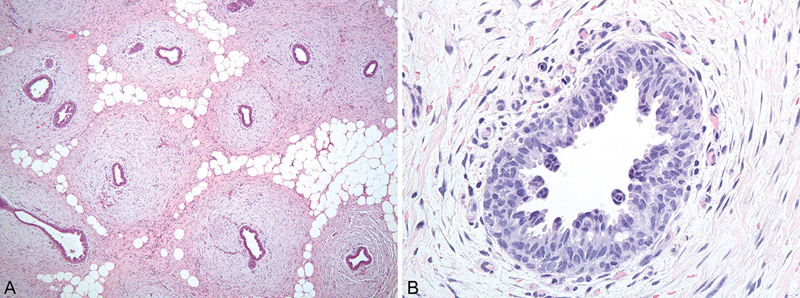

Fig. 15.01 Gynaecomastia of the male breast. Fibrous type. Source: Reiner A.

Fig. 15.02 Gynaecomastia of the male breast. Florid type. A Ducts within loose stroma. B Proliferation of ductal epithelium with tufts and micropapillary pattern. Source: (A,B) Reiner A.

Klinefelter syndrome, characterized by karyotype 47,XXY, is the most common chromosomal disorder associated with gynaecomastia. Patients with Klinefelter syndrome show gynaecomastia in 50–70% of cases. In rare cases, genetic alterations of the androgen receptor resulting in decreased androgen sensitivity may play a role in development of gynaecomastia {183}. In most cases, genetics does not play a role in this condition.

In most cases, gynaecomastia regresses within 2 years and therefore a “wait-and-watch” policy is often an appropriate clinical management strategy. Gynaecomastia is not considered to be a risk factor for the development of breast cancer in males, since the rates of gynaecomastia in male patients with breast cancer and in the general population are similar {1570}; however, some studies have reported a slightly increased risk of breast cancer in patients with gynaecomastia, which may be due to the fact that the same risk factors are associated with both conditions.

A. Reiner |

|

S. Badve |

|

Carcinoma of the male breast is a rare malignant epithelial tumour that is histologically identical to cancer of the female breast; both in situ and invasive variants can be seen.

ICD-O code |

8500/3 |

Breast cancer in males accounts for only < 1% of all cases of breast cancer and for 1% of cancers in males {647}. Globally, there is broad variation in the incidence of this disease. In the USA, with an estimated 1970 new cases of breast cancer being diagnosed in men in 2010, this disease represents 0.25% of all cancers in men and, with an estimated 390 deaths from breast cancer, 0.13% of all cancer deaths in men annually {1570}. In contrast, in the United Republic of Tanzania and areas of central Africa, breast cancer accounts for up to 6% of cancers in men {43}. Although it has been suggested that a slight increase occurred between 1975 and 2000, the incidence of male breast cancer seems to have remained stable or decreased slightly between 2000 and 2005.

Breast cancer tends to occur in a slightly older age group in men than in women (mean age, 67 versus 61 years), although younger males may also be affected. The bimodal age distribution observed in women with breast cancer is not seen in men.

Relatively little is known about the etiology of this disease, except that hormonal imbalance and environmental conditions are major contributing factors.

Conditions that seem to be consistently associated with elevated risk of male breast cancer are obesity and testicular disorders like cryptorchidism, mumps orchitis and testicular trauma. Diseases with a variable contribution to risk are liver cirrhosis, diabetes and hyperthyroidism. Drugs that cause hormonal imbalance, such as those used for the treatment of prostate cancer, may increase risk.

An increased risk of male breast cancer is reportedly associated with radiation to the chest wall and occupational exposure to radiation or electromagnetic fields. Some reports suggest an increased risk of development of breast carcinoma after occupational exposure to petrol and airline fuels.

In most studies, gynaecomastia is not considered to be a risk factor for breast cancer; however, some studies have documented a slightly increased risk {184, 185,430}, which may be attributable to the fact that the two conditions share the same risk factors.

Clinically, breast cancer in men presents as a painless firm mass situated in the subareolar region. Unlike gynaecomastia, the lesion tends to be located eccentrically in relation to the nipple. It is usually unilateral, but may rarely (0–1.9% of cases) involve both breasts {169}. Bloody nipple discharge may occur at a fairly early stage and is associated in 75% of cases with malignancy. Compared with the female breast, changes in the nipple areolar complex, seen as fixation, retraction, inversion and ulceration, occur with greater frequency in males. Paget disease of the nipple has been documented. Tumour characteristics related to advanced stage (tumour size > 2 cm and positive axillary lymph nodes) are more common in men. Palpable axillary nodes are detected in approximately 50% of cases. The management of these patients is similar to that for postmenopausal women with breast cancer.

Invasive carcinomas present as an irregular stellate or multinodular firm greyish-white mass with a mean diameter of 2–2.5 cm. Tumours tend to invade the nipple, overlying skin or pectoral muscle at a rather early stage. In situ carcinomas may present as partly cystic in appearance.

Although both ductal and lobular carcinoma in situ can occur in males, lobular carcinoma in situ is an extremely rare finding. The incidence of ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) is reported in up to 10% of all cases of breast cancer in males. It is histologically similar to that seen in females and all architectural patterns have been identified. There seems to be a relatively greater incidence of papillary intraductal carcinoma, and Paget disease and a decreased incidence of comedo necrosis in males than in females {584}.

Grading and assessment of steroid hormone receptors for DCIS should be performed in the same way as for carcinoma in situ in females.

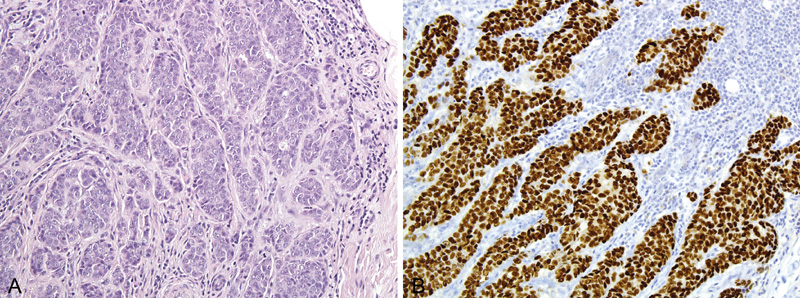

Fig. 15.03 Ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS). A Papillary-type DCIS in a male patient. B The papillary structures are lined by atypical cylindrical epithelium. Source: (A,B) Reiner A.

Invasive carcinoma of no special type (NST) is the most common type and is identical to that occurring in the female breast. Invasive papillary carcinoma is more common in males than in females, accounting for approximately for 2–4% of cases. Invasive lobular carcinoma is very rare, perhaps because of the lack of significant lobule formation in the male breast, and has been associated with exposure to estrogens and progesterone. Other histological types of tumour, such as medullary, mucinous or tubular carcinomas, are very rare. Histological grading should be applied as for invasive breast carcinoma in females. Carcinomas of grade 2 and 3 are reported in 80% of cases {430}. Currently no conclusive data exist on molecular subtypes.

Positivity for estrogen receptors is reported in > 90% of cases of breast cancer in men and for progesterone receptors in 80% of cases {19}. In order to select the optimal regimen of adjuvant therapy, assessment of hormone receptors and HER2 needs to be performed in the same manner as for breast cancer in women. National guidelines developed for the analysis of these markers in the female breast should be followed. Owing to the rarity of this disease, detailed data on HER2 expression are not available and a wide range of frequency of between 1% and 15% is reported in the literature {1236}. Molecular tests appear to yield results comparable to those for the female breast. Overall, robust analysis of large populations on biological markers is still needed.

Fig. 15.04 Invasive carcinoma of no special type (NST). A Invasive carcinoma NST in a male patient. B Immuno-histochemistry for estrogen receptor is strongly positive. Source: (A,B) Reiner A.

The ratio of primary to metastatic tumours is reported to be in the order of 25 : 1. The most frequent primary sites include prostate, colon, urinary bladder, malignant melanoma and lymphoma. Expression of markers such as prostate-specific antigen (PSA) has been reported in male breast cancers and should not be misinterpreted as indicating metastases from prostatic carcinoma {475,690}.

As in women, only a small proportion of breast cancers in men can be explained by genetic mutations. Approximately 15–20% of men with breast cancer report a family history of breast or ovarian cancer. Risk is particularly increased in cases of an affected sister (relative risk, 2.25) or both mother and sister (relative risk, 9.73) {185}. Men who inherit germline mutations in BRCA2 have an estimated lifetime risk of breast cancer of 5–10%, while risk in the general population is 0.1%. Male carriers of BRCA2 mutations have a risk of 7.1% of developing breast cancer by the age of 70 years and 8.4% by the age of 80 years {404}. The reported frequencies of male patients with breast cancer carrying BRCA2 mutations vary considerably and may be as high as almost 30% {344,461,492,1047,1048}. The association between germline mutations and breast cancer in men is weaker for BRCA1 than for BRCA2. The lifetime risk of developing breast cancer for men with germline mutations in BRCA1 is 1–5%. Breast cancer in men has also been associated with mutations in CHEK2, TP53 and PTEN tumour suppressor genes {430,1570}.

Klinefelter syndrome is a hereditary condition consisting of 47,XXY karyotype. Patients suffer from hormonal imbalance with higher ratio of estrogen to testosterone. The relative risk of developing breast cancer for men with this condition is reported to be between 20- and 50-fold {612}. The incidence of Klinefelter syndrome is reported to be 3–7.5% in men with breast cancer.

Mutations of the androgen receptor gene and polymorphism of the cytochrome 450 enyzme (CYP17) have been associated with an increased incidence of breast cancer in males in some studies {1570}.

The duration of symptoms before diagnosis tends to be longer for males than for females, but might be declining. The disease is driven mainly by known prognostic factors as TNM stage, tumour grade and estrogen-receptor status and is comparable to breast cancer in postmenopausal females. In addition, age and race seem to influence prognosis {715}. However, the disease is often more advanced at diagnosis in men, with > 40% of men with breast cancer presenting with stages III or IV {493}. This adversely influences overall prognosis. However, when stage-matched disease is considered, the prognosis for male and female patients is similar. Approximately 40% of male patients with breast cancer will die of causes other than their cancer. This likely reflects the higher rate of intercurrent illness associated with the older mean age of patients at diagnosis {715}.