William H. Kaempfer and Anton D. Lorwenberg

Economic sanctions constitute a less costly method of international pressure than outright hostilities and have gained wide approval as a tool for unilateral and bilateral foreign policy in a variety of situations. They have been most often applied in cases of foreign policy disputes (e.g., Iraqi aggression in Kuwait) or human rights issues (e.g., antiapartheid sanctions against South Africa) and occasionally as an adjunct to commercial policies, such as retaliation against countries accused of unduly restricting foreign access to their domestic markets or of engaging in dumping practices. Recent examples of the latter include U.S. trade restrictions imposed against Brazil for its refusal to allow the importation of U.S. computer products, similar restrictions on European Community agricultural exports in reprisal for European prohibitions on American hormone fed beef exports, and threatened U.S. tariffs on European white wine exports in retaliation for European soybean subsidies. Sanctions have even been contemplated or applied in disputes involving environmental issues and cross-border externalities. For instance, under pressure from conservation groups, the U.S. recently threatened sanctions against Japan for its commercial uses of almost extinct sea turtles.

But much controversy surrounds the use of sanctions. How are sanctions designed to cause policy change in target countries? Are sanctions used too frequently (or infrequently) as a policy option, or are they imposed for the wrong reasons? Why do sanctions so often lack significant economic impact? To address these questions, we will compare the traditional method of analysis of sanctions with an endogenous policy model of sanctions use and effectiveness based on the principles of public choice economics, which explores state behavior from the perspective of rational, individual decision making by participants. The insights of the public choice approach should help to explain some peculiarities surrounding the use of sanctions and some reasons why a sanctions regime may be a viable policy tool for changing the objectionable policies of foreign governments.

Popular wisdom about economic sanctions is that they are relatively ineffective. The traditional method by which sanctions are presumed to work is for the sanctioning country, in response to some objectionable policy in the target country, to impose economic damage on the target country, which will (supposedly) produce a change in the objectionable policy. This instrumental approach to sanctions relies on massive economic pressure being applied and suggests that only the most imposing economic bullies will have much of a chance at being successful sanctioners. Most economists believe that sanctions are ineffective because they do not impose significant economic damage upon the target nation. Economists are fond of pointing out that sanctions often do not have the damaging impact on the target economy that they are intended to have. Without the full cooperation of all existing or potential trading partners, boycotts of a target's exports or embargoes on its imports are difficult to achieve, because a competitive world market provides many sources of supply and alternate buyers. Willett and Jalalighajar point out that:

. . . except in unusual situations, alternate sources of supply and the transshipment of goods will nullify most of the intended effects of economic restrictions. A single country [imposing sanctions] seldom has sufficient control over the market of an important good for a boycott or embargo to have any major impact.1

To make trade sanctions effective in reducing the wealth of the target country, it is necessary that the sanctions be comprehensive in coverage (i.e., include most trade flows between the target and the rest of the world), and that the opportunities for redirecting trade be minimized. This latter condition, in turn, requires that the sanctioning countries account for almost the entire world market in the traded goods, or, failing this, that the cooperation of other countries be secured. In light of the strong incentives for an individual buyer or seller to renege on a collusive cartel agreement, this latter condition is seldom met.

The economic injury caused by trade sanctions can best be measured by a price effect felt in the target.2 When a target has sanctions enforced against it, its terms of trade worsen as the restricted number of import sources causes import prices to rise, while export prices fall due to a decrease in the number of export customers. This price effect mechanism demonstrates the incentives for nations (or individuals) to cheat against the sanctions or not join a multilateral sanctions effort. Any country that does not abide by the sanctions setup against a target has the opportunity to profiteer by exporting sanctioned goods to the target and importing the target's restricted exports at sanctions-distorted prices. The more severe the economic impact of the sanctions, the greater the opportunity for gain to any one willing to maintain trade with the target. This, incidentally, helps to explain why the bitter enemies of a target nation often are so willing to be sanctions busters. The conclusion is that the economic impact of sanctions is unlikely to cripple a target because of the availability of alternate sources and markets and the possibility of transshipment of goods.

A further, and more serious problem for the instrumental approach to sanctions relates to how the economic damage of sanctions is transformed into policy change in the target. The exact channel of transmission is obscure, but what is clear is that all too often the policy change desired by the sanctioning countries is not forthcoming in spite of sanctions that impose extensive economic damage. Consider, for instance, the continuing resistance by Iraq and by Serbian authorities in the former Yugoslavia to intense foreign sanctions pressures. Causing changes in objectionable policies in target countries is not simply a function of the intensity of economic damage from sanctions.

Public choice economics explores state behavior from the perspective of rational, individual decision making by participants. This branch of economic analysis suggests that many government policies, including international economic sanctions, can be viewed as endogenous policies that are the outcome of domestic political decisions in which the redistribution of domestic wealth plays a major factor.3 Thus, trade sanctions that restrict imports from target countries create benefits for producers of import substitutes in the sanctioning countries, at the expense of consumers of those goods.4 The interests that benefit from such policies or sanctions are sure to support them through the political process for their own ends. Some interest groups lobby for sanctions, not to obtain pecuniary gains, but to enhance the psychic welfare of their members. Thus, antiapartheid activists in the U.S. and other Western countries often sought sanctions against South Africa to assuage their members' dislike for the South African government's policies. On occasion groups with a pecuniary interest in sanctions will join forces with other groups seeking sanctions for largely nonpecuniary gains. For instance, U.S. sugar producers might join anti-Castro interests in lobbying for a boycott of Cuban sugar imports to the U.S. Kaempfer and Lowenbeig argue that many antiapartheid sanctions imposed by the U.S. and European Community in the late 1980s also served protectionist interests in those countries.5

Despite the motives of the groups lobbying for sanctions, any such restrictions on trade inevitably result in substantial costs for others in terms of higher prices and foregone trading opportunities. Given these costs of sanctions accruing to individuals and groups in the sanctioning countries, it is hardly surprising that sanctioners often deliberately apply sanctions that have weak economic impacts on the target countries. Elementary trade theory suggests that a sanctions regime that has a severe economic effect on one trading partner is likely also to impose substantial pain on the other partner. Therefore, governments in sanctioning countries will often attempt to meet the demands of interest groups pressuring them to apply sanctions by choosing fairly innocuous sanctions, usually on imports or exports which comprise small shares of the sanctioner's total market, thereby avoiding some wrath of other groups who might be hurt by more severe sanctions. This helps to explain why, for example, the U.S. Comprehensive Antiapartheid Act of 1986 included sanctions against South African textiles, steel, and agricultural goods, none of which represented a significant share of the U.S. market, but exempted various strategic metals of which South Africa is a major world supplier. Politicians üke to be seen to be "doing something" about a foreign government's violation of moral or ideological values, thereby satisfying interest groups lobbying for sanctions without simultaneously incurring any substantial costs that could raise the ire of other influential interest groups within the sanctioning polity.6

This interest-group analysis implies that the forms and severity of sanctions applied depend on several factors, including the relative influences of various interest groups within the polity of a sanctioning country, the ability of policymakers to act independently of interest-group pressures, and the amount of information possessed by individuals and groups within the sanctioning country regarding the objectionable policy of the target country. Thus, for example, the greater the awareness of injustices practiced by a target government, the greater the momentum of the sanctioning campaign. It follows that sanctions are often imposed not so much to initiate political changes in a target nation, but as a response to events that are already unfolding there. Resistance against the policies of the target government by its own citizens, for example, raises the profile of their struggle in the minds of sympathetic individuals abroad, and this enhanced consciousness of the problem leads to increased pressure on the sanctioning country's government to do something.7

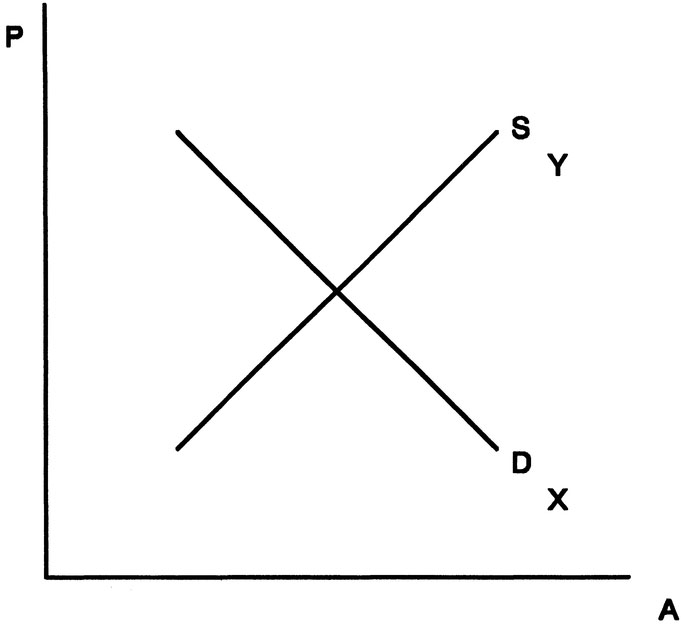

Just as the pressure for sanctions in sanctioning countries is a function of interest-group politics, so the effects of the sanctions in the target country also depend on interest-group politics in that country. Consider a simple interest-group model of the domestic polity of the target country,8 in which there are two domestic interest groups, X and Y, and a redistribution policy, A, which is viewed as objectionable by some foreigners and therefore attracts foreign sanctions. The objectionable policy might be aggression toward a neighboring country, human rights abuses, or destruction of some scarce natural resource. Suppose that members of group X benefit from policy A, which is a net transfer to members of X, whereas members of group Y are harmed by A because they are taxed to pay for the transfer to group X. Politicians decide the level of A by weighing the relative influences of group X and group Y. The presumption here is that politicians seek only to maximize their political support, by choosing policies in accordance with the relative influences of interest groups.9

The more resources a group is willing or able to allocate to political activity, the more effective it is in exerting political influence, and therefore the greater the relative weight which politicians attach to that group. Group X's preference for policy A is revealed in a downward sloping demand curve. The height of this curve at any given value of A is group X's marginal willingness to pay for policy A. This willingness to pay can be interpreted as a willingness to allocate resources to lobbying and political pressure to persuade the government to supply more A. Similarly, group Y reveals a downward sloping demand curve for reduced levels of A, or alternatively, an upward sloping "supply" curve for increased levels of A. Members of group Y are willing to allocate increasingly large amounts of resources at the margin to prevent A from increasing. Thus the height of their willingness-to-pay curve represents the "supply price" which politicians must incur, in terms of increased opposition from group Y, as a consequence of allowing A to increase.

As shown in Figure 6.1, the political equilibrium occurs at the intersection of these demand and supply curves. Support-maximizing politicians will supply A up to the point where X's marginal willingness to pay for an increase in A is equal to Y's marginal willingness to pay for a decrease in A.10 An increase in either group's political effectiveness will cause an upward shift of its willingness-to-pay curve. Thus, for example, an increase in X's effectiveness relative to Y's effectiveness will cause X's demand curve to shift up relative to Y's, and the equilibrium value of A will increase.

The preceding analysis implies that any exogenous event that increases X's political effectiveness by more than it increases Y's effectiveness, ceteris

paribus will cause an increase in the equilibrium level of A. Such an event, which shocks the domestic political system and alters the policy equilibrium, could emanate from outside the domestic polity. Examples include international sanctions, other foreign policy initiatives, lobbying activities of foreign interest groups, revolutions, or uprisings in neighboring countries. With sanctions, an embargo that reduces the incomes of both groups by the same amount will cause reductions of equal magnitude in the political effectiveness of both groups, and the equilibrium level of the objectionable policy A will not change. Only if the sanctions reduce the income of one group by more than that of the other will the equilibrium level of A change.11 Trade embargoes and financial sanctions, however, normally have widespread impacts on all groups in the target country. It is difficult to design sanctions to have selective economic impacts on different groups, especially due to the haphazard way that sanctions policies are generated out of interest-group politics in the sanctioning countries.12

Sanctions affect political processes in the target country not only through their income effects but, perhaps more significantly, through their impacts on each interest groups' effectiveness in organizing the collective action of its members. For example, a sanction that threatens to impose substantial costs on the supporters of the regime (group X), and perhaps threatens to escalate those costs in the future if the objectionable policy is not altered, might cause members of group X to become discouraged in their support for the group. This enhances free riding among X's members and reduces the group's political effectiveness. The equilibrium level of A falls. Alternatively, the sanctions might increase the ability of group X to organize collective action among its members, perhaps due to a rally-around-the-flag effect induced by unwelcome foreign intervention.13 The sanctions also can change the political effectiveness of the opposition group Y. Since sanctions are typically aimed against the ruling regime's policies, it is conceivable that the imposition of sanctions could be interpreted by members of group Y as foreign support for their struggle against X and its policy A. Members of group Y also might perceive that the sanctions have diminished the capacity of the existing government to retain power, which enhances the private return to individuals from opposing the government. In either case, members of Y might be willing to allocate more resources to political opposition, thereby diminishing free riding withinY and enhancing Y's political effectiveness. The result is a fall in equilibrium A.

Kaempfer and Lowenberg explore in greater detail the mechanisms linking sanctions with changes in political influences of interest groups in a target nation. Their analysis is based on a rational-choice model of collective action in which individuals are assumed to obtain utility from conforming with certain beliefs, even if conformity requires a sacrifice of income or other goods.14 For example, Higgs argues that an individual's utility depends not only on a basket of goods consumed, but also on "the degree to which one's self-perceived identity corresponds with the standards of one's chosen (or merely accepted) reference group, that is, with the tenets of the ideology one has embraced."15 Groups, in essence, reward their supporters with selective incentives, such as the right to share in a feeling of group identity or "political presence."16 Individuals obtain "reputational utility" from supporting the policy of a group, and this utility rises with the size of the group or the number of its supporters.17 The rationale for this assumption is that individuals "fortify their reputation(s) as supporters) of a given cause by rewarding other supporters and by withdrawing favors from opponents."18 People wishing to draw attention to their decision to support a group do so partly by complimenting and rewarding other supporters, because this carries more weight than a mere verbal declaration. Therefore, the individual obtains greater utility from joining in with a large group of peers than a smaller group, because the larger group creates a greater sense of group identity. Interest groups or political parties can foster greater support if they can convince individuals that their platforms are already popular. This helps to explain why a great deal of effort is often expended by the leaders of groups or parties in trying to convince people that their policies command the support of a considerable portion of the public.19

There are three distinct methods by which the leadership of an interest group can propagate public support for its policies:

All three cases can initiate a bandwagon process that raises support to a higher level in the population.

Pressures of foreign interest groups or events in foreign countries can serve as catalysts for all of the above mechanisms. First, individuals might revise their private beliefs and preferences when they discover that foreigners publicly profess belief in some policy objective. An individual's private preferences are shaped by his private beliefs, which, in turn, are partly dependent on the beliefs expressed publicly by other people. The greater the number of people who appear to hold an opinion, the greater the extent to which private beliefs and preferences will be altered to accord more closely with that opinion. Sanctions imposed against a target country can provide information to individuals in the target country that produces a change in private preferences regarding the objectionable policy pursued by the target's government.20

Second, foreign pressures might produce an increase in reputational utility awarded to individuals who support certain domestic interest groups, by increasing the effectiveness of those groups in rewarding their contributors with selective incentives. Thus, a signal of foreign support for the policies of a domestic group could be perceived as raising the probability of eventually achieving the goal sought by the group, which in turn might encourage activists in that group to work harder and devote more effort to organizing collective action. Third, sanctions, or foreign interest-group lobbying, might produce an increase in collective sentiment for the policies advocated by a domestic interest group. Such foreign pressures create the perception among individual citizens of the target nation that the policy pursued by their government is generally viewed as reprehensible by many people outside. This may also hold true for many individuals within the target country, implying that a large proportion of the population is strongly opposed to the policy and is willing to take action against it. In all three of the above cases, pressures, policies or events emanating from abroad serve to enhance the political effectiveness of certain domestic interest groups and reduce the effectiveness of others. These changes in the relative influences of competing interest groups can cause changes in public policy outcomes.

From the perspective of both the instrumental approach and the public choice approach, sanctions face many difficulties in being a successful element of a nation's foreign policy portfolio. On the one hand, the traditional, instrumental view of sanctions must face the fact that damaging economic sanctions will be difficult to apply in most situations and even more difficult to maintain. Public choice analysis suggests that damaging sanctions will be infrequently used because of the costs associated with them to sanctioning countries. Furthermore, when sanctions are used they can be expected to be distorted toward the ends of influential special interests, rather than being fine-tuned toward the goal of the sanctions.

On the other hand, the public choice approach does give some insight into exactly how sanctions might be expected to work in resolving international disputes. Objectionable policies in target countries are the result of the political processes of those countries and the decisions reached in those political systems. Sanctions can be effective by realigning the various interests at work in the political process. By strengthening the political effectiveness of internal interests seeking to change the objectionable policies of the target regime, sanctions can help to foster that change.

1. Thomas D. Willett and Mehrdad Jalalighajar, "U.S. Trade Policy and National Security," CATO Journal, Vol. 3, Winter 1983/84, p. 723.

2. William H. Kaempfer and Anton D. Lowenberg, International Economic Sanctions: A Public Choice Perspective (Boulder, Colo.: Westview Press, 1992).

3. The classics in the economic theory of regulation are George J. Stigler, "The Theory of Economic Regulation," Bell Journal of Economics and Management Science, Vol. 2, Spring 1971, pp. 3-21; and Sam Peltzman, "Toward a More General Theory of Regulation," Journal of Law and Economics, Vol. 19, August 1976, pp. 211-40.

4. William H. Kaempfer and Anton D. Lowenberg, "Sanctioning South Africa: The Politics Behind the Policies," CATO Journal, Vol. 8, Winter 1989, pp. 713-27.

5. Ibid.

6. For more details on this process, see Kaempfer and Lowenberg, "Sanctioning South Africa," pp. 713-27. See also Kaempfer and Lowenberg, International Economic Sanctions.

7. Thus, the Soweto riots in South Africa, the Tiananmen repression in China, and the reported rape and pillage of Bosnians by Serbs, all led to increased pressure on the U.S. government to impose economic and other sanctions against the offending nations.

8. This model is in the tradition of Peltzman, 'Theory of Regulation," pp. 211— 40; and Gary S. Becker, "A Theory of Competition Among Pressure Groups for Political Influence," Quarterly Journal of Economics, Vol. 98, August 1983, pp. 371-400. See also Gary S. Becker, "Public Policies, Pressure Groups, and Dead Weight Costs," Journal of Public Economics, Vol. 28, December 1985, pp. 329-47.

9. According to this conception of the political process, the government acts as a more or less impartial broker of interest group pressures. See Becker, "Theory of Competition," pp. 371-400; and Becker, "Public Policies," pp. 329-47. See also William H. Kaempfer and Anton D. Lowenberg, "The Theory of International Economic Sanctions: A Public Choice Approach," American Economic Review, Vol. 78, September 1988, pp. 786-93. Typically, interest groups deliver support to politicians in the form of votes or in the form of funds which can be used to finance campaigns, etc. In this stylized interest-group model, however, other forms of political expression, such as demonstrations and insurrection, are also effective ways of pressuring politicians or imposing costs associated with specific policies.

10. Peltzman, "Theory of Regulation," pp. 211-40.

11. We are assuming here that sanctions are, in general, income-reducing for both groups X and Y. It is possible, of course, the members of one group might actually receive net pecuniary gains as a consequence of sanctions.

12. Barry E. Carter, International Economic Sanctions: Improving the Haphazard U.S. Legal Regime (Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Press, 1988).

13. Kaempfer and Lowenberg, 'The Theory of International Economic Sanctions," pp. 786-93.

14. William H. Kaempfer and Anton D. Lowenberg, "Using Threshold Models to Explain International Relations," Public Choice, Vol. 73, June 1992, pp. 419-43.

15. Robert Higgs, Crisis and Leviathan: Critical Episodes in the Growth of American Government (New York: Oxford Univ. Press, 1987), p. 43.

16. Carole Jean Uhlaner, '"Relational Goods' and Participation: Incorporating Sociability into a Theory of Rational Action," Public Choice, Vol. 62, September 1989, pp. 253-85.

17. Timur Kuran, "Chameleon Voters and Public Choice," Public Choice, Vol. 53, No. 1,1987, pp. 53-78.

18. Timur Kuran, "Preference Falsification, Policy Continuity and Collective Conservatism," Economic Journal, Vol. 97, September 1987, p. 645.

19. Kuran, "Chameleon Voters," p. 72; and Uhlaner, '"Relational Goods'," p. 272.

20. Kuran, "Preference Falsification," p. 655.