For here is the easy question: can a generation—reared in affluence, schooled in self-importance, comparatively ignorant of national sacrifice—admit that the country can’t support it as grandly in its old age as it did in its youth?

—Howard J. Fineman (2006)

In the pre-2008 glow of prosperity and optimism, the buzz at the 2007 Fourth Annual “What’s Next? Boomer Business Summit” in Chicago was that business and corporate America were finally rediscovering the vast baby boomer market. Advertisers and marketers once studied and catered to the huge numbers of baby boomer children and adolescents. Corporate America’s first generational mass marketing effort in the 1950s had given the boomers much of their identity and culture via television and rock music. But as middle-aged boomers became so much more diverse in economic status and lifestyles, interest in generation-focused research waned. No more.

“Welcome to the revolution,” AARP’s chief brand officer Emilio Pardo told the three hundred registered conference attendees. More diverse and powerful than any previous generation, “boomers have transformed every life stage through which they’ve moved. Boomers want to feel good, look good, are still creative and idealistic. They want choices, have a voice (in national affairs), and they have ‘attitude.’ ” However, warned Pardo, boomers resent being stereotyped and approached only on the basis of age. “Focus on needs and make the individual connection,” he told the audience. AARP had found that boomers’ main concerns were financial security, health, community, the need to contribute and leave a legacy, and “play” (through leisure and recreation).

Mary Furlong, the prime mover behind the boomer business summits and author of Turning Silver into Gold, insisted that the aging boomer market could not be ignored.1 “There is no market opportunity larger than the boomers,” the Santa Clara University business professor told the conference. But marketing to boomers meant understanding the trends shaping their needs and wants: global markets, longevity, life stage transitions (“e-shocks” such as divorce or death of a loved one), technology, and spirituality. Boomers constituted a pot of gold for businesses in health, housing, travel, networking, and services. And busy boomers, seeking second careers and new life purposes, might propel an explosion in small business growth.2

Indeed, many audience members seemed to be women over age fifty who were in some sort of career transition—unemployed, marginally employed, or trying to start new careers. (Approximately two-thirds of the audience and speakers were women.) Corporate America was conspicuous by its relative absence. AARP was very much the primary sponsor and supplied several major speakers. Very few conference speakers and panelists were from major corporations. Intel, Phillips, Verizon, Microsoft, and Walmart were listed as minor sponsors.

Other boomer-business conferences reportedly failed to register much increased interest or participation from corporate America even before the Great Recession dampened enthusiasm—and budgets—for expanding market frontiers. Jennifer Mann, a Kansas City Star reporter, was puzzled by this neglect. The one hundred million consumers over age fifty control eight trillion dollars in assets, more than 70 percent of disposable dollars, “yet they barely get passing notice from American advertisers.” A major reason, marketing experts informed her, is that “a big problem in the ad agency world is that so many employees of agencies, particularly those who work on the creative side, are mostly in their 20s and 30s. Either they have no interest in working on campaigns targeted to older people, or they don’t know how to.”3

Nonetheless, through their sheer numbers, the boomer age wave is becoming a mass market inevitability. There has been an obvious surge of television and print media advertising toward boomers in the marketing realms noted by AARP’s Emilio Pardo: health-related products (from Viagra to Flow-Max to Cancer Care Centers), financial planning (the rock-and-roll advertisements of both Fidelity and Ameriprise Financial Services), and leisure and recreation. In the realm of “political marketing,” strategists in the 2008 presidential campaigns quickly realized that age had become a key voting behavior variable during the Democratic primary contest between boomer Hillary Clinton and self-advertised “postboomer” Barack Obama. Voters under thirty heavily favored Obama; those over age fifty—especially working-class women—generally favored Clinton. In the subsequent general election against John McCain, Obama won the under-thirty vote by 2–1.

In this chapter I am primarily interested in defining the key concept of generation and in outlining the basic cultural and demographic characteristics of baby boomers, especially the Older Boomers (born 1946–55). I will begin addressing questions that will recur throughout the book: Who are the boomers? What are their similarities? What are their differences? How have they changed? What are their needs, hopes, fears?

Boomers’ culture and demographics will strongly influence a broader question: Will they have sufficient cultural cohesion and economic and sociological convergence to politically mobilize? Or will their intense individualism, coupled with inequalities and other demographic differences, forever fragment them? And, if so, will AARP become their leader by default?

A vital preliminary question for marketers, political analysts, and social scientists is: Do boomers think of themselves as boomers? And do common generational experiences provide a lasting basis for shared perceptions on economics, politics, culture, and other realms?

Currently, boomer self-identification seems superficial at best. A recent survey by Boomer Insights Generation Group (a subunit of the huge Edelman marketing and public relations firm) finds that 71 percent of boomers identify themselves as such, but fully 28 percent do not.4 The latter are mostly Younger Boomers. A MetLife Mature Market Institute survey discovered that the oldest boomers were more likely to favor the label than the youngest. Eighty-three percent of the “Oldest Boomers” (born in 1946) liked the term or liked it somewhat, but nearly half of the Youngest Boomers (born in 1964) indicated that they didn’t like the term, and another 20 percent indicated that they didn’t know whether they liked it or not.5 Overall, though, a 2008 Harris Interactive poll found that boomers were more satisfied with their generational label than other age groups.6

The chief impediment to boomer generational self-identification is their fierce individualism—a hallmark trait found in nearly all research on boomers. Boomers’ individualism is also a headache for marketers and advertisers.

“Boomers refuse to be identified as part of a group,” former AARP Magazine editor Steve Slon told me. They don’t “feel part of the same tribe.”7 He should know. ARRP tried to market a monthly magazine specifically for boomer members titled My Generation. It failed. (AARP Magazine is now quietly segmented by subscribers’ age groups: fifties, sixties, and seventy or above.) “Please Don’t Call Us That!” was the title of Joe Queenan’s 2010 protest against the “baby boomer” label published on the AARP Web site.8

Boomers’ sensitivity to collective categorization forces marketers to group “the aging generation into categories that give the illusion of individuality, they hope, while still encompassing millions of people,” observed the New York Times reporter Charles Duhigg.9 Contemporary boomer-focused advertising sometimes gently references “generation” but never the word boomer.

Boomers’ lack of active generational identification has led to disappointments for Web site founders hoping to attract boomers as boomers. Eons.com is the prime example. Launched in 2005 with great fanfare by Jeff Taylor, founder of the successful Monster.com jobs Web site, Eons.com has narrowed its original broadly based focus on “living life on the flip side of 50.” The broader, more commercial and information-based mission (including an obituary page) has been dropped. Eons.com now operates primarily as a “friendship engine” for middle-aged people who want to meet others with similar interests via a wide range of affinity groups.10 Many other boomer Web sites are relationship oriented or, like Baby Boomer Headquarters.com, focused upon cultural nostalgia. Boomer-oriented Web sites come and go.11

But boomers’ collective consumer profile is nonetheless being mapped by entrepreneurs and corporations who track the Web sites boomers most frequently visit. (Again, as AARP’s Pardo noted, these are in the areas of finance, health, news, and recreation—though he did not publicly admit that for boomer men the latter includes both sports and pornography.)

Boomers likely will become much more age conscious as they cross various age thresholds, including “senior citizen discounts” (as low as age fifty), voluntary or forced retirement, and eligibility for Social Security (for reduced benefits at age sixty-two) and Medicare (age sixty-five). Most especially, boomers will acquire collective consciousness via intimations of mortality as they confront early indicators or the actual onset of chronic disease. (Cancer patient Diana Wagman was surprised to discover how many of her age forty- and fifty-something friends smoked marijuana. The reasons: pain—“We’re all beginning to fall apart . . . a couple of tokes really take the edge off the sciatica, rotator cuff injuries, irritable bowel syndrome, and migraine”; and anxiety—“to relax, to forget our disappointing careers and mask our terror of not just our own future but the future of our kids as well.”)12

As AARP’s savvy marketers have discovered, one broad basis of unity for Older Boomers is the music and television of their youth. Older Boomers came of age during an era that was unusually ethnically and culturally homogeneous. They were more uniformly molded than previous generations by postwar prosperity, suburbanization, television—and especially a youth-based commercial music industry. “They were the ‘Golden Kids,’ the first automobile-centered, ‘transistor teens,’ the focus of the radio music industry,” said Marc Fisher, Washington Post columnist and author of Something in the Air. “They are the first generation to think of themselves as such.”13

But demographic differences within this huge age cohort make it difficult for boomers—or others—to see anything like a unified group. AARP’s marketers are still studying the wide range of economic, educational, ethnic, and other differences among boomers. “More than ever, we realize boomers are a large and diverse generation,” AARP’s savvy former CEO Bill Novelli told me. “We have to do a lot of segmentation research.”14

Again: Who are the baby boomers, especially those Older Boomers born from 1946 to 1955? And what, exactly, is a generation?

No one has better defined and explained the term generation than the German sociologist Karl Mannheim in his classic 1923 essay “The Problem of Generations.”15 Mannheim located the study of generations within the wider enterprise of the sociology of knowledge: how individuals and groups come to “know what they know” through shared experiences and interpretations of events and processes within specific historical and sociocultural contexts.

Mannheim likened the concept of generation to the more popular Marxian concept of social class—a category of people who share similar economic or occupational positions. Just as an economic class can become an organized, active “class-conscious” group, so, too, can a generation. A generation shares the same historical location. They collectively experience and interpret the key events of that period. Many will think and respond to their shared passage in the same way. Distinctive generational identities may arise. They may begin to think and act as a group.

The concept of generation is often blurred with the related concepts of age cohort, period effects, and cohort effects. An “age cohort” is simply an inert demographic category. For example, the baby boom is usually defined as those born between 1946 and 1964. But as discussion inevitably turns to boomers’ social history and generational identity, that broad category is usually subdivided into two “minicohorts,” which I identify throughout this book as Older Boomers (born 1946–55) and Younger Boomers (born 1956–62). “Period effects” are events or processes during a particular historical time frame that affect all groups. For example, World War II affected most Americans in the 1940s; in the 1950s, the increased availability of television was a major information and entertainment transformation. An “age cohort effect” is the impact of such events on a particular age group during a particular life stage. For instance, men of military draft age were most directly affected by World War II; baby boomers “grew up” on television in the 1950s.16

The gerontologist Robert Binstock has illustrated how age cohort and period effects interacted in shaping older voters’ behavior in the 2008 elections. A majority of voters over sixty-five picked the Republican presidential candidate John McCain John McCain over Obama (53 to 45 percent). But Binstock demonstrates that the vote for McCain was particularly strong among voters age sixty-five to seventy-four, the “Eisenhower cohort” of older voters, who in their youth were strongly shaped by the 1950s presidency of Dwight Eisenhower. This political cohort has manifested these GOP-leaning “period effects” throughout their voting history.17

Mannheim maintained that, though an age cohort may obtain consciousness of itself as a generation, the salience of generational consciousness varies. Some generations may have a strong sense of collective consciousness; others may not. “The drama of youth” shapes each generation’s shared perspective as they make “potentially fresh contact with current events and ‘present problems.’”18 But subgroups or “generational units” may also encounter and interpret the same historical processes differently. For example, boomer subgroups differently interpreted the 1960s and its liberal legacy—resulting in the long-running “culture wars” that postboomer President Obama promised to transcend.

Throughout the book, I shall refer to five generational classifications drawn from studies by both the Pew Research Center and the Metlife Mature Market Institute:19

• The Greatest Generation: approximately 8 million people over age eighty-four (born 1910–27), who were molded as young adults by enduring the Great Depression and by fighting and winning World War II. They have been famously lionized by Ronald Reagan as the generation that “saved the world.”

• The Silent Generation: an estimated 31.5 million people aged sixty-six to eighty-three (born 1928–45), who had their childhood and adolescence shaped by the Great Depression and World War II and who moved into adulthood during the general era of conformity and prosperity in the postwar years.

• Baby Boomers: 78 million people aged forty-seven to sixty-five (born 1946–64), defined by a nineteen-year postwar spike in the birthrate. The Older Boomers were raised with high expectations during the prosperous 1950s and 1960s but were shaped by conflict and division over civil rights and the Vietnam War and also by several memorable historical events, ranging from the assassination of John F. Kennedy in 1963 to the Watergate scandal and resignation of Richard Nixon in the early 1970s; Younger Boomers came of age in the aftermath of all this and were shaped by the increasing educational and occupational changes wrought by globalization.

• Generation X: 49.6 million people aged thirty-five to forty-six (born 1965–76), also called the “Baby Bust,” who had to cope with changing institutional structures and have become defined by their entrepreneurial, savvy skills.

• Gen Y or “the Millennial Generation”: 76.5 million people aged seventeen to thirty-four (born 1977–94), who came of age in the twenty-first century. Nearly as large as the boomer generation, they are seen as very technologically savvy and as the most politically liberal—they were viewed as the backbone of Barack Obama’s presidential campaign.

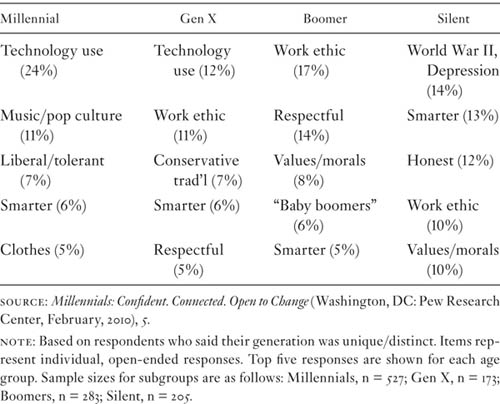

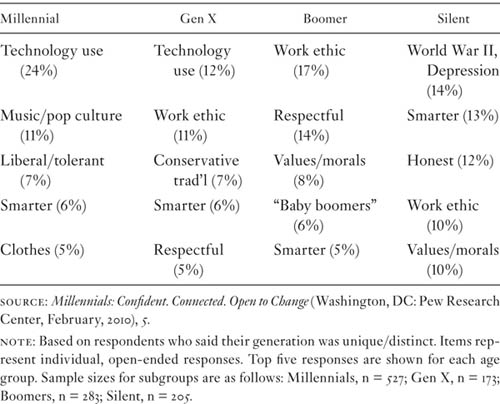

Generational identities are not strong but may be growing. When the Pew Research Center asked respondents from all adult age groups what made their own generation distinctive or “unique,” the top choice of traits among the competitive boomers was, not surprisingly, “work ethic”; somewhat more surprisingly, the generation with the 1960s rebellious stereotype also viewed itself as “respectful.” And a small percentage of boomers identified themselves as “baby boomers”—the only group to self-identify as a generation. Three of the four age groups cited “work ethic” as a key characteristic; Gen X and Millennials cited “technology use” (table 1). But these lists of cultural traits only begin to suggest the complexity of an identifiable, basic shared culture and ideology among baby boomers—one that has remained fairly consistent over time.

TABLE 1

What Makes Your Generation Unique?

A strong consensus in the growing literature on baby boomers is that their childhood and adolescent experiences forged a shared, though very general, sociological identity, especially among those who were suburban, white, and middle or upper middle class.20 The 1946–64 baby boom resulted from (1) the postponement of childbearing by older women during the Depression and World War II, (2) a three-year drop in women’s average age of first childbirth, and (3) an overall rise in the number of births. The boom was sustained by unusually favorable economic and cultural trends. The long period of postwar economic prosperity and the suburban housing boom encouraged a large number of babies. Family life was idealized, children and marriage were celebrated, and a powerful, popular “procreation ethic” took hold during the longest economic expansion in U.S. history. In this environment “contraceptive vigilance could be relaxed because penalties for not doing so were not so harsh.”21

“Many a child’s life did indeed match the Happy Days image. . . . The future looked happy and uncomplicated like the Jetsons,” observe Generations coauthors William Strauss and Neil Howe.22 Indeed, nearly 80 percent of boomers report being raised in “Ozzie and Harriet” two-parent households—in contrast to the 61 percent figure for today’s twenty-something Millennials.23

The sociologist Paul Light agrees that boomers were raised in a prosperous era that encouraged value change, tolerance, and rejection of traditional social roles; they internalized optimism and great expectations forged by television and Madison Avenue. But Light emphasizes that competitive economic and social crowding fostered individualism and detachment from institutions. Indeed, Boomers’ notorious focus on the self was inevitable, a “generational sensibility rooted in numbers and mindset—boomers could not have turned out any other way,” conclude Yankelovich researchers Walker Smith and Ann Clurman.24

The stereotype of adolescent and young adult boomers as widely involved in radical politics and the hedonistic counterculture is just that. Strauss and Howe point out that political radicals and “hippies” represented only 10 to 15 percent of boomers; many boomers’ opposition to the Vietnam War was motivated more by their aversion to the military draft.25 (Hollywood producer Steven Spielberg admitted as much to a Rolling Stone reporter: “I was obsessed with staying out of Vietnam. . . . My immediate political activity was based on self-preservation.”)26

Indeed, even the most idealistic of the nineteen influential boomer change agents studied by Michael Gross became more pragmatic as they moved into middle age. “The counter-culturalists’ revolutionary pipe dreams have been overturned or co-opted. . . . Like First Baby Boomer Bill Clinton we are not so much committed moralists as morally flexible, ambition-driven pragmatists far more like the parents we rebelled against than we may care to admit.”27

Yet boomers’ youthful idealism and social movement participation yielded lasting, positive changes. Greater Generation author Leonard Steinhorn correctly argues that the 1960s liberation movements, especially feminism and the civil rights movement, permanently changed boomers and society.28 The historian Steve Gillon also credits the importance of feminism in changing society, especially by propelling boomer women into the workplace and by providing new models for movement building and political networking.29

But the 1960s social movements and resultant changes also polarized boomers and other Americans—a split played out for nearly four decades of “culture wars.” This dueling liberal-conservative boomer political heritage was epitomized in the vastly different political personas of the first two boomer presidents, Bill Clinton and George W. Bush. Gillon sees boomers as a “generation at war with itself,” agreeing with earlier observations by Generations authors William Strauss and Neil Howe that the culture wars reflect class, religious, and geographical divides.30

Strauss and Howe flatly reject the notion of self-interested aging boomer politics. An intensely idealistic and moralistic generation, boomers, with their zeal for social reform and the greater good, will ultimately transcend their self-centered individualism and the specter of age-based politics. However, as we shall see in chapter 3, the sometimes militant idealism and reformism of boomers in their youth was largely the ideology of the educated, evolving professional and managerial boomer upper middle class. Those further down the economic ladder faced increasingly competitive labor markets in which idealism quickly gave way to pragmatic realism regarding rising economic instability and survival in a world dominated by global supercapitalism.

Beginning in the 1970s, increasingly competitive job markets changed college students’ educational and career choices. Men, especially, were forced to become more practical. As Landon Jones noted, “In the sixties, students studied sociology so they could change the world; in the seventies they studied psychology so they could change themselves; in the eighties they will study business administration so they can survive.”31

The journalist Tom Wolfe skewered upper-middle-class middle-aged boomers as the self-obsessed, self-indulgent “Me Generation.”32 But the social scientist Paul Light detailed a somewhat darker boomer ethos: a work-driven rugged individualism detached from civic society and mistrustful of government. He saw middle-aged boomers as motivated by quests for (1) individual economic opportunity and (2) personal meaning and safety. Boomers became mistrustful of large institutions and developed little long-term loyalty. They tried to find a philosophy of life in their work—often at the expense of personal life and civic participation.33 Their intense individualism and self-reliance bred an unforgiving outlook. “More than any other generation, Boomers blame failure on the individual. . . . They feel in control of their financial lives.”34 Light detected an ideological drift toward “political and social survivalism” and a proclivity for privatization of public problems.35 (Ten years later, the Harvard political scientist Robert Putnam, in his classic book Bowling Alone, marshaled survey research data to confirm suspected trends in boomers’ declining civic involvement.)36

As the twenty-first century dawned, AARP’s “Boomers at Midlife” survey and focus group data (2002, 2004) found that middle-aged boomers remained resilient, optimistic individualists with a can-do ideology that attributed individual success—or lack thereof—to personal factors such as motivation, confidence, or willpower. One in three respondents stated that “nothing” was keeping them from achieving their goals. Nearly two-thirds of older boomers (64 percent) and three-fourths of younger boomers (73 percent) strongly agreed with the statement “What happens to me in the future mostly depends on me”—even though fewer than half perceived “a great deal” of personal control over future personal finances, physical health, or work or career. Nearly 60 percent remained confident that they were “very likely” to achieve work/career goals, while another 53 percent thought they would reach financial goals.37

In their 2007 book Generation Ageless, Yankelovich researchers Smith and Clurman identified three universal boomer traits: (1) youthfulness, (2) impact—the desire to have influence and make a difference, and (3) belief in personal development through empowerment and continuous progression.38 Like other researchers, they described boomers as individualistic innovators and rule breakers who emphasized control and choice and who were flexible and comfortable with change. Attitudes toward government were characteristically guarded: 80.5 percent agreed that “government isn’t the best answer for most of the problems we face.” (Yet a paradox: nearly 70 percent agreed that people had the right to “the best medical care.”) Boomers still didn’t believe much in the system and thought it might have to be reformed from the “outside.” And they might be the ones to do it because “aging boomers have a lot of fight left in them.”39

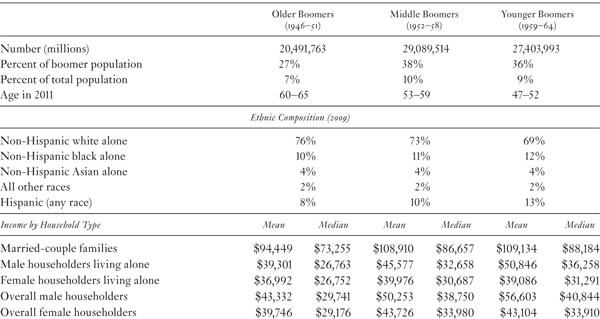

In 2010, Metlife Mature Market Institute completed an analysis of Older Boomers (born 1946–51), Middle Boomers (born 1952–58), and Younger Boomers (born 1959–64). The characteristics of these three subgroups are portrayed in table 2.

Generally speaking, occupational and educational changes are most evident among men in these three boomer subgroups. Older Boomer men are better educated and have a more upscale occupational profile and a more conventional marital status. Nearly 35 percent have a bachelor’s degree or higher versus 30 percent of Middle Boomer men and 28 percent of Younger Boomer men. Forty-two percent of Older Boomer men are in management, professional, and related occupations compared to 37 percent of Middle Boomer men and 36 percent of Younger Boomer men; the latter are the most “blue collar,” with 19 percent employed in “construction, extraction, and maintenance.”

TABLE 2

Characteristics of Major Boomer Subgroups

Evidence of cultural changes toward marriage is striking: 75 percent of the Older Boomer men are married versus only 70 percent of Middle Boomer men and 65 percent of Younger Boomer men; only 7.5 percent of Older Boomer men are “never married,” but that figure more than doubles for Younger Boomer men to 16.7 percent.

Older Boomers are the smallest of the three groups, the “whitest” (76 percent non-Hispanic white), and, somewhat surprisingly, the lowest paid. But among the three subgroups what is most striking are gender differences. The portrait of Older Boomers was largely reinforced in a Metlife Institute study published a few months later of “Early Boomers” (aged fifty-five to sixty-four). The newer report focused upon how demographic characteristics might affect retirement prospects. The profile of Early Boomers suggested that they were likely to work longer because the oldest segment (aged sixty to sixty-four) had the highest male college graduation rates ever achieved (before or since): 37 percent. (Thirty percent of Early Boomer women had college degrees, but college graduation trends for women have risen steadily: thus women aged thirty to thirty-four have the highest graduation level of 38 percent.) Early Boomers’ labor force participation is at an all-time high, despite the gloomy economy. This is probably because three-quarters of Early Boomer women and three-fifths of Early Boomer men were in more recession-proof white-collar jobs. This positive occupational tilt also explains relatively high incomes: fully 37 percent of Early Boomer married couples earned more than $100,000 per year; another 15 percent of married couples earned $75,000 to $100,000 and 20 percent earned $50,000 to $75,000.40

About two-thirds of these Early Boomers were estimated to be grandparents—and the effects of the Great Recession register in data that a rising number of them are raising, or helping to raise, their grandchildren. This, in turn, may be related to the finding that approximately one in four Early Boomer families had adult children at home. (For reasons that are unexplained, the “Early Boomers” in the newer report had 10 percent fewer married couples than the “Older Boomers” of the previous study. Only 56 percent of Early Boomers were married couples; 26 percent were women householders, and 18 percent were male householders.)41

Neither of the 2010 Metlife studies contained data on assets, net worth, or political attitudes. A benchmark study by Annamaria Lusardi and Olivia Mitchell, using data from the federal government’s 2004 Health and Retirement Study, explored the important dimensions of inequality within boomer ranks. The median total net worth of Older Boomers (born 1946–53) was just $151,500. Subtract housing and any business assets and this figure dropped to a paltry $48,000. But for the top 10 percent asset levels were considerably higher, $888,010 and $536,700 respectively, and for the top 5 percent they were $1,327,000 and $903,600.42

A 2007 Metlife profile of a “typical” Older Boomer just turning sixty-two suggested a positive relationship between age and net worth: average annual income was $71,400 and their average household net worth (excluding home value) was $257,800. They were comfortable being identified as baby boomers and didn’t think they would be “old” for another seventeen years. Twice as many were conservative as liberal.43

But the stock market crash and real estate recession have taken a toll on boomers’ net worth. By 2009 the Center for Economic Policy and Research found that boomers’ median net worth had fallen 45 to 50 percent; a partial recovery later that year led Moody’s to recalculate this loss as closer to 25 percent.44

Social class is one of the most powerful factors shaping political behavior and the life course. Rising inequality of incomes and assets among boomers mirrors increasing economic polarization throughout the nation. Economic inequalities, in turn, are strongly structured by race, education, and family status. How these inequalities might affect ideological divisions and prospects of generational mobilization will be more closely analyzed in chapter 3. For now, it should be kept in mind that inequalities cut two ways. On the one hand, relatively wealthy boomers might be more insulated against adverse policy or social changes and less likely to engage in organized political response; conversely, a sizable, less fortunate, anxious “boomer proletariat” might constitute a vulnerable, potent base for political protest.

Economically, two dominant trends have defined the baby boom generation for the past thirty years. First, the large number of young boomer men flooding the labor force in the 1970s and 1980s depressed wages, creating a lifelong income decline relative to that of their fathers. The second trend was partly in response to the first: large numbers of boomer women went to work full time outside the home. Birth Quake author Diane Macunovich concluded that by the end of the twentieth century “the much heralded closing of the male-female wage gap has resulted largely from a lowering of male wages, rather than from a real rise in female wages.”45

To achieve middle-class lifestyles, boomers postponed marriage, had fewer children, and became dependent on two incomes. The proliferation of two-income families led to what Elizabeth Warren and Amelia Tiagi term the “two-income trap.” As family incomes rose, the costs of middle-class life (especially housing and education) escalated even faster, stretching budgets and raising bankruptcy rates. The advent of global markets produced greater swings in annual family incomes and enhanced the value of advanced degrees.46

In their classic 2004 study The Lives and Times of Baby Boomers, Mary Elizabeth Hughes and Angela M. O’Rand found sharp inequalities among boomers structured by race, marital status, and educational attainment. Boomers cohabited, delayed marriage, divorced, and remarried, developing a pattern of “serial monogamy” along with a variety of other family forms. In becoming the best-educated generation in history, they closed and even reversed gender gaps in education. Conversely, race and ethnic educational attainment gaps increased. (Among Early Baby Boomers, 25 percent of whites were college graduates, compared to 45 percent of U.S.-born Asians and about 15 percent of blacks and U.S.-born Hispanics.) The result: highly educated, white and Asian two-income, stable families pulled further away from others with less education, such as immigrant Hispanics and especially large numbers of black one-parent families.47

The Brookings Institution demographer William Frey updated and confirmed these trends in 2010. The sheer size of the tsunami, he noted, would magnify the boomers’ distinctive social and demographic attributes, especially inequality. And, noting changes in family structure, Frey predicted that boomers’ “higher rates of divorce and separation, lower rates of marriage and fewer children signal the potential for greater divisions in seniorhood between those who will live comfortably and those who will have fewer resources available to them.”48

As we shall see in subsequent chapters, these wide economic variations in boomers’ incomes, assets, education, and family status profoundly structure competing political and cultural worldviews that thus far have fragmented any potential boomer political cohesion. Indeed, income and education strongly affect perceptions of whether retirement will be “the Golden Years”—or something far less.

For most Americans, increased income, education, and occupational levels are generally associated with positive feelings about oneself and society, greater political awareness, and higher levels of civic and political participation. Two major studies of how boomers “envision retirement” with surprisingly similar findings on how economic status influences retirement perspectives were done before the 2008 economic turmoil: one by AARP and another by Merrill Lynch.49

A 2004 AARP “Boomers Envision Retirement” study (of a representative sample of 2,001 adults, aged thirty-eight to fifty-seven) sorted boomers into five groups. Thirty-two percent were “Self Reliants.” They had the highest median household income ($82,000), the highest percentages in professional and white-collar occupations and with bachelor-or-above degrees (43 percent), and the highest percent married (84 percent) and white (83 percent). Self Reliants contributed to retirement accounts and were confident about their retirement years.

“Enthusiasts” were 14 percent of the sample. They were also 83 percent white and were second to the Self Reliants in terms of median income ($78,000), occupation, educational attainment (33 percent with undergraduate degrees or higher), and percent married (79 percent); and they were the most eager to retire completely from all work. “The Anxious” were 17 percent of the sample, third in terms of income ($60,000) and percent married (64 percent); they were similar to the Enthusiasts in terms of percent in white-collar occupations (34 percent) and college graduates (33 percent). The Anxious were nervous about retirement savings and were skeptical about retirement health care coverage and Social Security and Medicare reliability.

“Today’s Traditionalists” were 22 percent of the sample. Their median household income was $52,000; 53 percent were in blue-collar jobs; 63 percent were married and 15 percent never-married or single; they had the highest percentage of African Americans at 19 percent and were the most confident about Social Security and Medicare. “The Strugglers,” 15 percent of the respondents, had the lowest household income ($32,000), the highest percentage of single/never-married (16 percent) and the lowest percentage married (57 percent); 60 percent had blue-collar jobs; 57 percent were female (the highest percentage of all groups), and 17 percent were black (the second-highest percentage of all groups). Not unexpectedly, they had little saved for retirement and were the most pessimistic about it. (Significantly, the groups did not vary in terms of median age.)

Merrill Lynch’s 2005 “New Retirement” telephone survey of 3,448 baby boomers found five similar subgroups with strong correlations between income, assets, and retirement outlook: “Wealth Builders” (20 percent of those interviewed, with an average income of $84,000), “Empowered Trailblazers” (18 percent, $83,000), “Anxious Idealists” (20 percent, $66,000), “Leisure Lifers” (13 percent, $64,000), and “Stretched and Stressed” (18 percent, $60,000).50 In the Merrill Lynch survey, nearly half the respondents were self-confident and positive; only one-third of the AARP respondents were confident.

In both surveys, future health insurance affordability was a potent source of anxiety. Fifty-eight percent of the AARP respondents didn’t expect employer contributions to their postretirement health insurance; 43 percent didn’t expect Medicare to cover most of their medical needs. The Merrill Lynch survey uncovered an especially grim insecurity: more respondents feared lack of affordable health insurance (53 percent) than death (17 percent).51

The findings of these studies are probably still valid. Indeed, the Great Recession has likely reinforced these patterns. New research presented in chapter 4 suggests that those in the higher income brackets have been more likely to remain employed, have regained much of the value of their retirement portfolios, and have therefore probably remained more confident about their retirement futures. The most “anxious” middle groups have likely become more anxious. And low-income Americans have been most vulnerable to being forced into an early and uncomfortable retirement by unemployment.

In terms of this book’s focus on whether aging boomers may respond politically to threatening economic and social changes, the AARP and Merrill Lynch studies suggest that boomers’ readiness to identify with one another in a common political cause (via voting or social movements) will depend upon their resources, their confidence, and their fears. As the data presented in early this chapter suggest, boomers tend to be strongly individualistic and optimistic. This outlook has profoundly hindered their ability to recognize and cope with systematic economic and occupational changes that were well under way even before the Great Recession.

Studies of boomers’ history and surveys about their attitudes and values tell us little about how boomers have actually negotiated the realities of aging—and the worst economic crisis since the 1930s. At the outset of what was to become known as the Great Recession, I interviewed several experts and consultants who were on the front lines of research or consulting with aging boomers, especially with regard to the workplace. (Later in the book, I will deal with boomers’ reactions to the middle and late phases of the long, deep downturn.)

AARP’s savvy brand officer Emilio Pardo noted boomers’ abiding sense of optimism and opportunity. “Boomers think ‘there’s always one more tomorrow.’ ”52 But many financial planners and career consultants put a much darker spin on boomers’ hopes for tomorrow: denial.

SeasonedPro founder and career consultant Richard Katz found that boomers’ emphasis on individual responsibility and blame was inhibiting their ability to seek needed counsel and advice. “There’s a cultural stigma against seeking help,” sighed Katz, who has worked extensively with university alumni groups. “It’s not considered cool. . . . And it’s a double stigma if you get help and then still can’t get a job.” This is especially true for men, he added.

Katz believes age discrimination in the workplace persists despite antidiscrimination laws and labor shortage forecasts. “Employers aren’t willing to pay for baby boomers,” he’s concluded. “I’ve heard the forecasts of labor shortages and need to hire older workers. But I don’t see it. Send them people over age thirty-five and they’ll say, ‘That’s not what we’re looking for.’ ” Katz admits that some older workers with engineering or highly specialized skills may fare better. But he grimly recalled a University of Houston career conference where 250 employers set up recruitment tables for new graduates, but only eighteen employers did so in the SeasonedPro section. Thus Katz had recently reoriented SeasonedPro to upwardly mobile career seekers in their thirties and forties. (I suggested he rename his company and Web site “Lightly SeasonedPro.” We both laughed uneasily.)53

Carleen MacKay, an expert on mature workforces and coauthor of Return of the Boomers, thought boomers’ sheer numbers made them different. She was less certain about their alleged commitment to individualism. Instead, what struck MacKay about these “Kennedy generation optimists” was that they were “pioneers in consumerism, debt, and materialism.” Boomers, she stated, had a proclivity for instant gratification. They bought huge houses with the result that “the house owns them, not vice versa.” She worried that too many boomers were “bad planners.” They were totally unprepared for the economic dislocations that MacKay foresaw: waves of layoffs and pension problems–caused by the increasing devaluation of “overpriced” midlevel jobs via globalization and outsourcing—that were gradually eroding the status and security of middle-class jobs.

She was equally unimpressed with the foresight of boomers who still had job security and lifetime pensions. “When I asked a conference of California public employees in their forties and fifties how many would take early retirement, virtually all of them raised their hands,” MacKay told me. “But most hadn’t thought at all about what they’d do afterwards.”54

The career transition consultant Andrew Johnson found that his generally upscale clientele in Southern California banking and real estate were adjusting to changing job markets through individualistic efforts of retraining and persistent job searches. Nevertheless, he saw occasional signs of a longing to return to New Deal–era government safety nets. Like many others interviewed for this book, he saw something of a backlash against information overload and the plethora of choices in health care and retirement planning. “People don’t want to look out for themselves all the time. They accept the new changes, but they don’t necessarily like them.”55

Carleen MacKay offered a darker reason behind boomers’ unease. “Many of them are surprised that they are maturing in an America that no longer wants them in the workplace.”