The Neglect of the Greek-Speaking Widows (6:1–7)

A serious problem arises that threatens to undo the unity of the church during a time of great growth. A sharp schism has developed between two social groups within the church. The early characterization of the Christian community as “one in heart and mind” (4:32) has given way to partiality and strife.

BUST OF ALEXANDER THE GREAT

This passage describes how the apostles handle this problem and resolve the conflict. They do so by appointing additional leaders for the church. These new leaders possess a strong blend of practical savvy and Spirit-inspired living. By handling this problem effectively, the church continues to grow even more.

Disciples (6:1). The term “disciple” (mathētēs) is used regularly in the Gospels to refer to a follower of Jesus of Nazareth. Even though Jesus is now exalted to the right hand of the Father, his followers are still referred to as “disciples.” The word itself is surprisingly rare in the Old Testament (only one time; 1 Chron. 25:18), but master-disciple relationships were common in the Old Testament and Judaism, as we see in the relationship between prophets and their students (e.g. 1 Sam. 19:20–24; 2 Kings 4:1, 38) and the rabbis and their students. The common Old Testament way of referring to the relationship is by the term “follow” (akoloutheō). In the Greek world, however, the term “disciple” was commonly used. At the time of the New Testament era, it was frequently used in the sense of an “adherent,” such as we might find in the relationships between the philosopher Socrates and his students (or after his death, those who commit their lives to his teaching).79

Complained (6:1). The word for complaint (gongysmos) is colorful and strong. Luke probably chooses it to recall the griping of the Hebrews when they were in the desert shortly after God provided them a miraculous deliverance through Moses (see Ex. 16:7–9; Num. 11:1).

The Grecian Jews … Hebraic Jews (6:1). “Grecian Jews” is a rather imprecise translation of an expression that means “Greek-speaking Jews.” The term hellenistēs frequently means “Greek-speaking” in a variety of ancient literature.80 The church father Chrysostom reports that Luke uses the term “Hellenists” for “those speaking Greek.”81 The contrast here is with those who did not speak Greek fluently: “the Hebraic Jews” (hebraioi). This latter group is designated as “Hebrews” because they were much more comfortable with Hebrew or Aramaic.

Jews who were raised in Palestine spoke Aramaic as their native tongue. This was a Semitic language that had many similarities to Hebrew. Aramaic was the dominant language of the Near East for centuries before the time of Christ. Many Jews in Palestine, especially in Jerusalem and Judea, continued to use Hebrew (as evidenced for instance in the Dead Sea Scrolls). Most would also probably have learned some measure of Greek—this is now the language of the Roman empire—but certainly would not have felt as comfortable in this language as their native tongue.82

Many Jews raised outside of Palestine, such as in North Africa, Egypt, and Asia Minor, would never have learned Hebrew. Their principal language would have been Greek. When they settled in Jerusalem, these “Hellenists” would have enjoyed meeting together in a synagogue where the Scriptures were read in Greek, prayer was in Greek, and conversation was in Greek.

It is doubtful that there were any serious doctrinal differences between the “Hellenists” and the “Hebrews” at this stage. These “Hellenists” tended to be just as zealous about the temple, the law, and the festivals as any Jew raised in Jerusalem (Saul/Paul is a good case in point).83 There may have been some cultural differences, however, that further distinguished them from the “Hebrews,” such as taste in foods, musical styles, and literature. The “Hebrews,” on the other hand, in their efforts not to be tainted by Hellenistic culture, may have been more isolationist and ethnocentric, perhaps going to great lengths to avoid contact with other Jews who did not accept their own outlook and interpretation of purity regulations.84

The daily distribution of food (6:1). Many Jews immigrated to Jerusalem to spend their final years in the Holy City and die there. Often the men preceded their wives in death, and the widows were then left with no immediate family to support them and care for their daily needs. There is some evidence that widows even traveled from Diaspora locations to Jerusalem. There is a higher proportion of women’s names in Greek ossuary (a burial box for bones) inscriptions.85

Jerusalem leaders had put together an organized system of relief for the destitute. Rabbinic literature testifies to the existence of both a daily and a weekly distribution of relief. The daily distribution (tamḥûy) typically consisted of bread, beans, and fruit. The weekly distribution (quppāh) consisted of food and clothing.86 Although the rabbinic evidence is later than the New Testament, there is little doubt that some sort of organized relief was in place in Jerusalem at this time. The widows in Acts, however, are Christian Jews and are deriving aid from their new Christian community. Presumably the apostles have instituted a similar kind of system of relief to that offered by the temple officials.

Luke does not tell us who is to blame for this discriminatory treatment faced by the Greek-speaking Jewish widows. The apostles, however, do not undertake a blame-finding investigation. They immediately seek a solution to the problem through finding men of integrity to serve as leaders to provide leadership to the relief effort in the church.

To wait on tables (6:2). The verb translated “to wait” is diakonein from which is derived diakonoi (“deacons”). Consequently, some have assumed that this passage provides the background to the office of “deacon” in the early church.87 This is not the case. First of all, the word diakoneō was widely used with the simple and non-technical sense of “to serve.” Such is the case in Mark 10:45, when Jesus said of himself: “The Son of Man did not come to be served, but to serve, and give his life as a ransom for many.” Second, it is unlikely that Luke would tell the story about the origin of the office and never use the term “deacons” (diakonoi) for the first office holders.88 In this situation, an ad hoc group of leaders is formed to take care of a pressing matter in the church.

Choose seven men (6:3). There is some precedent in Judaism for choosing seven men to lead. When Josephus took command of Galilee, he appointed seven magistrates in every town of the region.89 This reflects an implementation of his understanding of Deuteronomy 16:18 (“Appoint judges and officials for each of your tribes in every town”): “Let there be seven men to judge in every city, and these such as have been before most zealous in the exercise of virtue and righteousness.”90 There is also some later rabbinic evidence for the appointment of seven men to carry out various kinds of tasks.91

Known to be full of the Spirit and wisdom (6:3). These men need to excel not only in natural abilities to administrate and lead, but they need to demonstrate the presence of the Holy Spirit in their lives. This experience of the life in the Spirit is the mark of the new age and the fulfillment of Old Testament prophecy.

To prayer and the ministry of the word (6:4). The Twelve want to devote more time to prayer. Their time in prayer probably includes but greatly exceeds the typical Jewish practice of praying three times a day. Their “ministry of the word” would have included both evangelistic proclamation (which, in a Jewish context, would have involved demonstrating that Jesus was the Messiah based on the Old Testament) and teaching the many thousands who recently embraced Jesus as Messiah and joined the Christian community. Integral to this ministry would be passing on the tradition of Jesus—giving accounts of his ministry and faithfully reciting his teaching.

Stephen (6:5). See comments on 6:8.

Philip, Procorus, Nicanor, Timon, Parmenas, and Nicolas (6:5). The surprising twist to this story is that it appears that the people choose seven men who are “Hellenists.” That is, they all come from the offended group within the church. Each of the seven men has a Greek name (amply attested by occurrences in Greek inscriptions and literature). The fact that Nicolas is a convert to Judaism and is thus a Gentile indicates that the others are Greek-speaking Jews.

Beyond this passage, nothing further is known about Procorus, Nicanor, Timon, and Parmenas. Some of the church fathers believed that Nicolas is the founder of the heretical sect of the Nicolaitans referred to in Revelation 2:6, 15.92 There is no evidence to support this assertion. It is more likely that some make an unwarranted connection because of the similarity of names. Philip, as we will see in Acts 8, becomes a zealous ambassador of the gospel in Samaria and later in Caesarea (21:8).

A convert to Judaism (6:5). See comments on 2:11.

Laid their hands on them (6:6). The practice of the laying on of hands in the Old Testament often occurred in the context of sacrifice and symbolized the transfer of sins from the offender to the sacrificial being.93 The clearest example of this is when Aaron placed his two hands on the head of the scapegoat (Lev. 16:21). But the laying on of hands also took place for the conferral of blessing, as when Jacob blessed each of his sons (Gen. 48:18), and for the conferral of authority on a successor, as when Moses commissioned Joshua (Num. 27:18–23; Deut. 34:9). The latter example became important in rabbinic Judaism as a model for its ordination practice.94 The laying on of hands in this passage, however, is not a rite of ordination. It represents a conferral of authority and blessing on these seven leaders. They are already full of the Spirit, but now they are commissioned to fulfill a special responsibility in the community.

A large number of priests became obedient to the faith (6:7). It must have been encouraging to the Christian community in Jerusalem to see many priests becoming followers of Jesus. Luke does not specify if some of these individuals are from the high priestly families or whether all come from the order of ordinary priests (like John the Baptist’s father Zechariah). The ordinary priests, living throughout Palestine, were organized into twenty-four different rotations, with each group coming and serving a two-week stint (in addition to serving at the three pilgrim festivals). There are many ordinary priests—J. Jeremias estimates eighteen thousand, a number that might even be low95—who serve the Jerusalem temple.

It is also possible that among these new converts were Essene priests, with perhaps some from the Qumran community. The original core of this community was of priestly descent. Some Essenes were residents in Jerusalem and may have occupied an area of the city known as the “Essene Quarter.”96

The Story of Stephen (6:8–15)

Luke now tells the remarkable story of one of these seven men. Although we never see Stephen waiting on tables, we find him doing many of the things the apostles themselves are doing. His bold proclamation of the Word and his success make him a threat to the Jerusalem leaders. He is arrested and interrogated. Like Jesus, he faces false witnesses whose testimony leads to his conviction and death. Whereas earlier, the apostles face imprisonment and flogging for their proclamation of Jesus as Messiah, now the persecution reaches a much higher level.

Stephen (6:8). Luke devotes a significant amount of space to telling the story of this exemplary, Spirit-filled man (6:8–8:2). He has a rather common Greek name that means, “crown” or “wreath.” The victor in an athletic contest is crowned with a stephanos (see 1 Cor. 9:25). We know nothing of his life prior to his appearance here in Acts. As the others, he is likely a Greek-speaking Jewish settler in Jerusalem originally from somewhere in the empire.

Great wonders and miraculous signs among the people (6:8). Because of his faith and his receptivity to the Spirit’s work, God is able to do powerful works through Stephen. These probably include miraculous healings and the casting out of unclean spirits among the unbelieving Jews. Because of these remarkable signs, he is likely gaining a strong and receptive hearing for his proclamation of the gospel.

The Synagogue of the Freedmen (6:9). The term “freedmen” is a translation of the Greek word Libertinoi, itself a transliteration of the Latin Libertini. This is an expression used to designate emancipated slaves. This particular synagogue thus probably consisted of Jews from Rome who were freed from slavery and migrated back to Jerusalem. They banded together and formed their own synagogue where they could worship and praise God in Greek.

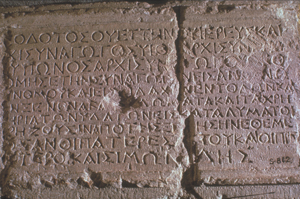

THEODOTUS INSCRIPTION

A first-century inscription attesting to one of the synagogues in Jerusalem.

During the many battles that took place in Palestine leading up to the conquering of Palestine by the Romans (63 B.C.), many Jews were captured, taken to Rome, and sold as slaves. Philo refers to a Jewish sector of the city of Rome populated mainly by emancipated Jewish slaves who had gained Roman citizenship.97 The Roman historian Tacitus refers to four thousand Gentile “freedmen” (libertini) in Rome who became tainted with the superstitions of the Jewish rites.98 Many of these assuredly became proselytes.

Jews of Cyrene and Alexandria as well as the provinces of Cilicia and Asia (6:9). The language of the passage in Greek is somewhat ambiguous. There are three possibilities for understanding what Luke is referring to: (1) there is one synagogue—the Libertinoi—comprised of Jews from four regions; (2) there are two synagogues—one called the Libertinoi consisting of members from Cyrene and Alexandria and another synagogue with members from Cilicia and Asia; or (3) there are five synagogues—the one called Libertinoi consisting of emancipated Jews from Rome as well as four other synagogues associated with Jews from each of the other four geographical areas. The evidence slightly favors the third view, in part because the Libertinoi most likely refers to emancipated Jews from Rome.99 We know from Acts 24:12 that there is more than one synagogue in the city. We also know based on other sources that Jews often formed synagogue congregations based on their places of origin.100

The synagogue of the Alexandrians is mentioned a number of times in rabbinic literature. A passage in a Jewish Tosephta speaks of a rabbi purchasing the “synagogue of the Alexandrians.”101 Interestingly, the parallel passage in the Babylonian Talmud refers to it as the synagogue of the Tarsians (i.e., Cilicians).102 There is no direct evidence of a Cyrenian synagogue, but archaeologists have discovered the burial place of a Jewish family from Cyrene in Jerusalem.103

Words of blasphemy against Moses (6:11). The first accusation that the witnesses bring is that Stephen is speaking against the Jewish law. There is nothing in Stephen’s address to indicate that he attacks the law. The fact that Luke refers to the witnesses as false, indicates that he disagrees with their charge.

Sanhedrin (6:12). See “The Sanhedrin” at 4:11.

Speaking against this holy place (6:13). The false witnesses also accuse Stephen of speaking against the temple. The evidence for this charge is the claim that Stephen says that “Jesus of Nazareth will destroy this place.” This echoes the false charge brought against Jesus in his trial (Mark 14:57–59). While it is true that Jesus said that the temple would be destroyed and “not one stone will be left on another” (Luke 21:6), this is a long way from saying that Jesus himself would destroy it. Interestingly, the community behind the gnostic Gospel of Thomas attributes the destruction of the temple to Jesus.104