The Evangelization of Iconium (14:1–7)

After their mixed reception at Antioch, the missionary partners travel nearly a hundred miles to Iconium where they receive a similar response to their preaching.

Went as usual into the Jewish synagogue (14:1). Paul begins his outreach in Iconium at the Jewish synagogue in spite of the fact that he angrily turns to the Jewish leaders in Antioch of Pisidia and exclaims, “We turn now to the Gentiles” (13:46). Because of the presence of Gentile God-fearers, the synagogue is the best place to begin his witness to the Gentiles.

SOUTH GALATIA

The Jews who refused to believe stirred up the Gentiles (14:2). This is precisely the response he encounters in Antioch (13:46, 50) and will later experience in Thessalonica (17:5) and elsewhere. Many Jews as well as Gentiles respond to the gospel.

Miraculous signs and wonders (14:3). The people of the city see miraculous things happen as Paul and Barnabas minister here. These signs and wonders no doubt include healings and exorcisms. As at other times in the outreach of the early church, God intervenes in these dramatic ways to demonstrate the authenticity of the message about his grace that these two missionaries are proclaiming. These miracles serve as background to a comment Paul later makes to the Galatian believers in his letter: “Does God give you his Spirit and work miracles among you because you observe the law, or because you believe what you heard?” (Gal. 3:5).

With the apostles (14:4). Luke here explicitly labels Paul and Barnabas “apostles,” as he does again in verse 14. Apparently, Luke uses the title in two different ways: someone who travels with Jesus in his earthly ministry, has seen him risen from the dead, and constitutes one of “the Twelve”; and someone set apart by the Holy Spirt for an evangelistic mission and then commissioned and “sent out” by the local church.267

The Lycaonian cities (14:6). In A.D. 25, the “Lycaonian cities” of Lystra and Derbe were incorporated into the Roman province of Galatia. Luke, however, demonstrates his knowledge of the former territorial divisions, to which the local populace was still sensitive. The territory of Lycaonia reached northeast nearly as far as Iconium and bordered Cilicia on the south, Cappadocia to the east, Phrygia and the former ethnic territory of Galatia to the north, and Pisidia and Isauria to the west.268 Another of the principal cities of Lycaonia was Laranda, located about twenty miles east southeast of Derbe in the direction of Tarsus.

LYSTRA

The tel of the ancient city (center right).

The Evangelization of Lystra (14:8–21a)

Undaunted by the threats of stoning and persecution, Paul and Barnabas travel on to the cities of Lystra and Derbe. An unusual situation surfaces at Lystra where the two are mistaken to be gods.

Lame from birth and had never walked (14:8). Luke’s statement about the severity of the handicap highlights the “wonder” (see 14:3) of this healing. For the man to walk and jump, God has to restore bone mass and a significant amount of muscle.

In the Lycaonian language (14:11). While these people know Latin and Greek, they still retain facility in their native Anatolian dialect, which Luke refers to as Lykaonisti. Usage of this dialect in the area around Lystra persisted until as late as the fifth century A.D. and beyond.269 There is evidence that two Christian monasteries in Constantinople (Byzantium) founded in the sixth century used the Lycaonian language in their liturgy.270 Inscriptions in the dialects of other nearby Anatolian languages also survive (namely, Carian, Sidetic, and Pisidian).

The gods have come down to us in human form (14:11). The famous first-century Roman poet Ovid tells a story about Zeus and Hermes taking mortal form and visiting an elderly couple in their humble Phrygian countryside home. Leading up to this, Zeus and Hermes visited a thousand homes seeking shelter and rest but were repeatedly spurned, their true identities being concealed. It was not until they came to the home of Philemon and Baucis that they found hospitality. The old couple welcomed the two visitors, fed them well, and prepared for them a place to rest. Not knowing that they were entertaining gods “in the guise of human beings,” the old couple finally learned the identity of their heavenly visitors. The gods then led Philemon and Baucis to the top of a hill and mercifully spared them from a devastating flood sent in judgment on the inhospitable inhabitants of the region. Their humble home was miraculously transformed into a marble temple.271 If this local legend was known to the inhabitants of Lystra, it may help to explain their identification of the missionaries as Zeus and Hermes and their eagerness to honor them.

There is also inscriptional evidence from Lystra attesting the local worship of Zeus and Hermes. A stone relief found at Kavak (in the territory of Lystra) depicts Hermes accompanied by the eagle of Zeus. In the city of Lystra, a stone was discovered that portrays Hermes and a second god (possibly the earth-god Gē or Zeus Epēkoos).272

Barnabas they called Zeus, and Paul they called Hermes (14:12). Although Zeus (Jupiter) is the head of the pantheon of gods, it is not surprising that Paul is associated with Hermes (Mercury) instead of Zeus. Hermes was widely regarded as the messenger of Zeus. One ancient writer describes Hermes as the god “who is the leader in speaking.”273

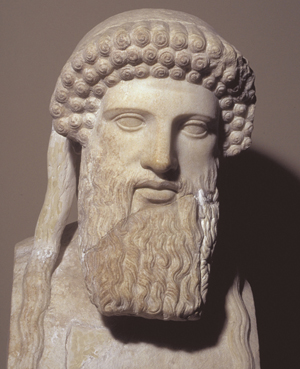

HERMES

ZEUS

The priest of Zeus (14:13). Another group of manuscripts uses the plural, “the priests of Zeus,” which more accurately reflects the historical situation. It was common for such temples to have a college of priests.274

Whose temple was just outside the city (14:13). The temple has not yet been discovered. Archaeologists, however, have found many statues and inscriptions attesting the worship of Zeus and Hermes in this region. None of these, however, dates any earlier than the third century A.D.275

Brought bulls and wreaths to the city gates (14:13). The bulls are brought to be sacrificed. Such animals were typically adorned with garlands on their way to be slaughtered.276

BULLS AND WREATHS

The altar of Domitian in the Ephesos museum in Selçuk.

They tore their clothes (14:14). In Jewish culture, extreme grief is often expressed by tearing one’s clothes. It was an outward expression of what the person was feeling inwardly. “The destructive action reveals the sudden and sharp emotion that overshadows all ordinary concerns, such as care for appearance and possessions.”277 Reuben and Jacob both tore their clothes when they thought Joseph had been killed (Gen. 37:29, 34). Many of Israel’s leaders tore their clothes when God’s honor was impugned.278 When the Sanhedrin heard an account of blasphemy against God, the judges “stand up on their feet and rend their garments, and they may not mend them again.”279 This is what the high priest did at the trial of Jesus (see Matt. 26:65; Mark 14:63).

Men, why are you doing this? (14:15). This question marks the beginning of a short address that Paul gives to the crowd, wherein he appeals to them to desist in their acclaiming of him and Barnabas as gods, and points them to the one true God. What Luke records in the span of these three verses is a brief summary of what is likely a longer address. This is not exactly an evangelistic message, at least from what we know of it, because it makes no mention of Jesus or the elements of the kerygma—the message of the death, resurrection, and exaltation of Christ, drawing the implications of this event for the forgiveness of sins and a relationship with God.

There are similarities between this address and his message to the Greeks on the Areopagus in Athens (see 17:22–30). These are the only two occasions where Luke records Paul’s preaching to non-Jews. In both instances Paul contextualizes his message to people who do not know the Scriptures. The apostle stresses natural revelation (focusing on God as Creator and the providential sustainer of the world) and the emptiness of idolatry while avoiding a recounting of Israel’s history or how Jesus fulfills Jewish prophecies about a coming Messiah.

From these worthless things (14:15). Jews typically regarded idolatry as “empty” (mataios). One Jewish writer writes, “For just as one’s dish is useless when it is broken, so are the gods of the heathen, when they have been set up in the temples.”280 Another Jewish writer asserts that “men themselves are much more powerful than the gods whom they vainly worship.”281

The living God (14:15). Frequently throughout the Old Testament, the one God of Israel is described as “the living God.” Joshua tells the people of Israel as they enter the promised land that “the living God is among you.”282 A popular story is told in Palestinian Judaism shortly before the birth of Christ about Daniel challenging the Persian king about his worship of the statue of Bel, the patron deity of Babylon: “The king revered it and went every day to worship it. But Daniel worshiped his own God. So the king said to him, ‘Why do you not worship Bel?’ He answered, ‘Because I do not revere idols made with hands, but the living God, who created heaven and earth and has dominion over all living creatures.’ ”283 This story well depicts the Jewish attitude toward idols.

Paul’s comments are offensive to these Gentile worshipers of Zeus. The implication of what Paul says is that other gods, including Zeus and Hermes, are not alive.

Who made heaven and earth and sea and everything in them (14:15). This line repeats the same words we find used in support of the fourth commandment enjoining Israel to keep the Sabbath holy: “For in six days the LORD made the heavens and the earth, the sea, and all that is in them, but he rested on the seventh day” (Ex. 20:11). But God is also extolled as Creator in these words in other Old Testament and Jewish contexts.284

In the past, he let all nations go their own way (14:16). Throughout the history of Israel, God directly and repeatedly intervened by revealing himself to them, making them his own people, redeeming them from slavery, guiding and leading them, bestowing on them his law, speaking to them through the prophets, and giving them promises of a bright future. God did not respond to the Gentile nations in the same way, but he did not leave them without a witness. Paul’s comments here echo what he says elsewhere to the Greeks on the Areopagus (17:30) and to the Romans in his letter (Rom. 1:28).

He has shown kindness by giving you rain from heaven (14:17). God’s witness to the Gentile nations is not through their religions, which Paul has characterized as “worthless.” The living God’s providential care for the nations by providing them with land, rain, crops, and the enjoyment of life is a sufficient testimony to point these people to a greater reality. A Jewish rabbi said that if a person sees “mountains, hills, seas, rivers and deserts he should say, ‘Blessed is the author of creation,’ ” and “for rain and good tidings he should say, ‘Blessed is he, the good and the doer of good.’ ”285

Paul’s remarks here may have functioned as a direct polemic against the local cult religions. Zeus was popularly worshiped as the god of weather and the one who provided vegetation.286

Some Jews came from Antioch and Iconium (14:19). It is surprising that Paul’s Jewish opponents from Antioch (near Pisidia) travel a hundred miles to oppose him in Lystra. Do they receive word from Jews living in Lystra about what is transpiring there? Contact between the cities of Antioch and Lystra, in spite of the distance, is evidenced in part by a statue of Concordia that the people of Lystra erected in the city of Antioch.287

They stoned Paul and dragged him outside the city (14:19). There is great irony in the fact that the apostle goes from being venerated as a god to an object of derision whom the people try to kill. Luke does not say why they do not attempt to stone Barnabas as well. It may point to the role Paul is playing in the events—especially in the speaking. Since stoning was a distinctively Jewish form of punishment, we can assume that these Jewish opponents from Antioch and Iconium threw the rocks while the Gentile crowd from Lystra looked on.

But after the disciples had gathered around him, he got up and went back into the city (14:20). Since the crowd supposes that Paul is dead, the apostle probably is seriously injured—at least stoned in the head and knocked unconscious. Some interpreters have thought that God works a miracle in raising Paul up in response to the prayers of these who “had gathered around him.” This may be the case.

They preached the good news in that city (14:21). Luke says nothing about any of the events surrounding the ministry of Paul and Barnabas in Derbe. Yet he does say that many people there become followers of Christ.

Revisiting and Strengthening the New Galatian Churches (14:21b–23)

Then they returned to Lystra, Iconium and Antioch (14:21). After being expelled from Antioch, plotted against in Iconium, and nearly stoned to death in Lystra, it is a tribute to God’s power in their lives that Paul and Barnabas even consider stepping foot in those cities again. They are willing to risk their lives for the sake of the gospel, however, and their love and concern for the well-being of these new converts drive them to take incredible risks.

SOUTH GALATIA

Appointed elders for them in each church (14:23). Knowing that these fledgling communities need leadership to facilitate their continuing growth in the Lord, Paul and Barnabas appoint presbyteroi. The plural suggests that a group of gifted men is selected for each church and share equally in the task of leading the respective congregations.288 Paul’s model for this form of leadership comes from the synagogue pattern and from how he sees the network of house churches structured in Jerusalem (see comments on 11:30).

Returning to Antioch, Syria (14:24–28)

Rather than continuing to other cities in Asia Minor to proclaim the gospel, the two decide to return to their sending church in Antioch of Syria. Luke does not state why they decide to return at this juncture, but it may have had to do with a sense of accomplishment of their work in south Galatia and a desire to solicit further support for a more extensive future trip.

They went down to Attalia (14:25). Attalia served as the harbor for Perga, the capital of the Roman province of Pamphylia. Although Luke does not explicitly tell us that Paul’s boat came into Attalia when they first arrived in this region (see 13:13), this was probably his point of entry. This time, however, Paul and Barnabas spend some time preaching the gospel in Perga (five miles upriver from Attalia), although we have no report of the response.

ATTALIA

They sailed back to Antioch (14:26). The journey has now come full-circle, and these two emissaries return to the church in Syria that sent them out.

The door of faith to the Gentiles (14:27). The missionary report alludes to the language of Jesus, who described himself as “the door” to salvation (John 10:9). At the heart of Paul’s preaching is the presentation of faith as the means by which one enters the door and receives justification and forgiveness of sins (see Acts 13:39).

They stayed there a long time (14:28). It is impossible to know exactly how long the two stay in Antioch and resume their ministry to the many believers there. It is certainly less than a year and may have been just a few months. It is during this time and prior to the Jerusalem Council that Paul receives word that a group of Jewish believers zealous for the law visits the new believers in south Galatia and begin to subvert his teaching. In response, Paul writes his first letter—Galatians.