The Jerusalem Council (15:1–29)

For many years, the Jewish people welcomed Gentiles into their covenant community provided that they turned from their idols to the one true God and adhered to the Jewish law—most notably by being circumcised. Now that the Messiah of Israel has come and an ingathering of Gentiles into the newly constituted people of God is happening, a number of law-observant Jews are wondering why Paul and the church at Antioch are not insisting that the Gentile converts keep the law. This issue becomes divisive and threatens to split the movement. The wisest course of action is to convene a meeting with the leaders of the Jerusalem church and reach a mutual understanding that will govern the movement as more and more Gentiles put their faith in Jesus Christ.

JUDEA AND ANTIOCH

Some men came down from Judea to Antioch (15:1). A faction within the Jerusalem church consisting of believers who have been Pharisees (see 15:5) are disturbed about the way Gentiles are being admitted into the church. They are upset that Gentile believers are not being circumcised as commanded by the law. To make sure that the Antioch church is not lax in its fidelity to God’s law, a group of them make the three hundred-mile journey to Syria to press this issue. Verse 24 makes it clear that they are not authorized by the leaders of the Jerusalem church.

Unless you are circumcised, according to the custom taught by Moses, you cannot be saved (15:1). These Jewish believers, committed to the law of God, make it clear to the leaders of the church at Antioch that circumcision is essential to salvation. They are not excluding Gentiles from becoming authentic members of the people of God; they are simply insisting that they be circumcised.

Sharp dispute (15:2). The apostle Paul is equally convinced that circumcision is not necessary as a sign of the covenant for the newly constituted people of God. For Paul, this is not an issue on which the two parties should amiably “agree to differ.” This is central to the gospel and needs to be settled by the principal leaders of the church—the apostles and elders in Jerusalem.

They traveled through Phoenicia and Samaria (15:3). This three hundred-mile journey is not an overnight ride. It takes a minimum of twenty days and probably takes them a month, given their stops along the way. The fruit of the evangelism of those Jerusalem believers scattered by the persecution is now seen (see 11:19). Communities of believers have been established not only in the territory of Phoenicia, but also in Samaria (see 8:5–25). Paul and Barnabas stop and fellowship with a number of these groups of believers. They encourage them by telling them the story of numerous Gentile conversions in Antioch, on the island of Cyprus, and in the regions of Cilicia and southern Galatia.

SAMARIA

The place of sacrifice on Mount Gerizim.

PHOENICIA

The modern city of Sidon.

Believers who belonged to the party of the Pharisees (15:5). Not surprisingly, those who are the most vocal opponents of Paul’s position were Pharisees prior to their conversion. In accepting Jesus as the Messiah of Israel, they have not changed their distinctive views about the law.

And required to obey the law of Moses (15:5). Here we find that the issue actually involves more than circumcision. The Pharisaic believers want the Gentiles to observe the entire law of Moses as a condition of membership in the people of God. This includes especially the laws regulating ritual purity, Sabbath observance, and the celebration of the key Jewish festivals. In the letter he writes to the Galatians just prior to the council, Paul explains the implications of the Pharisaic believers’ view: “Again I declare to every man who lets himself be circumcised that he is obligated to obey the whole law” (Gal. 5:3).

The apostles and elders met to consider this question (15:6). Of the Twelve, Luke only explicitly mentions Peter, but presumably at least some of the others are present (see comments on 11:30). The fact that leaders from the church at Antioch travel to Jerusalem and meet with the leaders there shows the ongoing oversight for the entire movement exerted by the Jerusalem church and the commitment of both churches to be unified in the essential aspects of the gospel.

Some time ago God made a choice (15:7). Peter, the principal leader among the Twelve, stands up and addresses the entire group. He begins by calling them to reflect back on the beginning of the Christian movement when God sovereignly chooses him to explain the gospel to Cornelius and his household some ten years ago.

He accepted them by giving the Holy Spirit to them (15:8). Peter does not take a “middle of the road” position on the issue. He presents a case firmly on the side of Paul and opposed to the Pharisaic believers. His argument is that God poured out his Spirit on Cornelius and his household before they received circumcision (and actually even before they received water baptism). For Peter, this signified God’s sovereign decision to incorporate Gentiles into the one people of God solely on the basis of faith apart from a requirement of circumcision or law obedience.

He purified their hearts by faith (15:9). “Purification” and cleansing (katharisas) from sin no longer comes from the blood of the sacrifices, but by putting one’s trust in the Messiah, who has poured out his blood to make purification for sin.289

You try to test God (15:10). Whether they do so wittingly or unwittingly, Peter accuses his Pharisaic brothers of putting God to the test by requiring circumcision and law-obedience of Gentile believers. Testing God is tantamount to unbelief. The Israelites repeatedly tested God in the desert by distrusting him and grumbling against what he was doing among them.290 God himself has decided to free Christians (Jewish and Gentile) from the former obligations of circumcision and law-observance. To insist on these rites and practices now, in light of the significance of the cross and resurrection of Christ, is to ignore the significance of what God has done and to blatantly provoke him.

Putting on the necks of the disciples a yoke (15:10). A yoke is a harness put around the neck and front quarters of a large animal enabling it to pull a farm implement or a wagon. It comes to represent any kind of burden someone endures and, in some instances, an image of bondage. Sin, for instance, is a yoke around a person’s neck (Lam. 1:14). Jews referred to the law of Moses as a yoke, but one that protected them from the dangers of this world. The Mishnah says, “He that takes upon himself the yoke of the Law, from him shall be taken away the yoke of the kingdom [that is, the troubles that come from the earthly rulers] and the yoke of worldly care; but he that throws off the yoke of the Law, upon him shall be laid the yoke of the kingdom and the yoke of worldly care.”291 Peter, however, takes a much more negative view of the law—especially in terms of the numerous rituals, purity regulations, and various observances—viewing it as an inappropriate burden to place on Gentiles as a condition for their salvation.

YOKE

The man is plowing his field in the Nile Valley with a pair of bulls harnessed to a wooden yoke.

Neither we nor our fathers have been able to bear (15:10). The law, taken together with the protective “fence” of traditions and regulations the Pharisees have built around it, is beyond human ability to keep. In this, Peter reflects the teaching of his master, who said to the Pharisees, “You load people down with burdens they can hardly carry, and you yourselves will not lift one finger to help them” (Luke 11:46).

We believe it is through the grace of our Lord Jesus that we are saved (15:11). The main point of Peter’s argument is not how difficult the law is to keep, but rather its irrelevance now for salvation. Peter states unequivocally that salvation—for Jews as well as for Gentiles—is through grace and not by successfully completing the various requirements of the law. In this he is perfectly in line with Paul, who also stresses that salvation was a gift of God’s grace (Eph. 2:8–9; Gal. 2:15–16). For Peter, the case of Cornelius and his household is paradigmatic. Their reception of the Spirit upon exercising faith in the Lord Jesus is sufficient evidence to convince him that God now receives Gentiles as his new covenant people solely on the basis of faith.

The whole assembly became silent (15:12). The silence of the crowd of believers may imply that the majority are convinced by Peter and agree with him.292 It must be remembered, however, that Luke does not give us a full account of the proceedings in Jerusalem, an account that would have taken many pages. Now the group listens to Paul and Barnabas describe the ways God has been at work through them in reaching Gentiles. The “signs and wonders” give further evidence of God’s own sovereign inclusion of Gentiles on the basis of faith and not through fulfilling the requirements of the law.

James spoke up (15:13). On James, see comments on 12:17. He appears to have become one of the most significant leaders in the Jerusalem church. Like Peter, he does not lend his support to the position of the Pharisaic believers. He agrees with Paul and Barnabas in affirming that circumcision and law-obedience are not essential for obtaining salvation.

Simon (15:14). James refers to Peter by his Hebrew name (see 2 Peter 1:1).

Taking from the Gentiles a people for himself (15:14). God originally chose Israel, not the Gentiles (ethnē), to be his special people: “For you are a people holy to the LORD your God. Out of all the peoples (ethnē) on the face of the earth, the LORD has chosen you to be his treasured possession” (Deut. 14:2). James recognizes that there has been a fundamental change in the way God constitutes his people. Yet this change is not unanticipated, since Zechariah 2:11 predicted a future period when “many nations [ethnē] will be joined with the LORD in that day and will become my people.” Once again, the conversion of Cornelius and his household is seen to mark this development in the plan of God.

I will return and rebuild David’s fallen tent (15:16). James appeals to Amos 9:11–12 to provide further support for what Peter has said and what actually happened in the case of Cornelius and the many other Gentiles who believed the gospel and received the Spirit. This prophecy anticipates Gentiles becoming a part of God’s people when the house of David is restored. The royal line of David reigning over Israel came to an end when Jehoiachin and Zedekiah were exiled to Babylon (2 Kings 24:15–25:7). This prophecy anticipates a reestablishment of David’s kingdom. The Qumran community also understood this passage in a messianic sense.293

The coming of Jesus marks the restoration of “David’s fallen tent.” The conviction that Jesus of Nazareth is David’s descendant who assumes the throne is at the heart of the gospel message (see Acts 2:29–36; 13:22–23).

That the remnant of men may seek the Lord, and all the Gentiles who bear my name (15:17). With the coming of Jesus as the Davidic Messiah, the extension of his reign over the Gentiles has now taken place. They enter the covenant people of God not by “becoming Jews,” however, but as Gentiles by putting their faith in Jesus. The “remnant” is more properly translated “all other peoples”—that is, all the various ethnic groups comprising the Gentiles. There are many Old Testament prophecies that speak of the conversion of the nations in the messianic age.294

We should not make it difficult for the Gentiles (15:19). James comes down squarely on the side of Peter, Paul, and Barnabas. Because of his relationship with Peter as one of the “pillars” of the Jerusalem church (Gal. 2:7), it is doubtful that this decision reflects a change in his thinking from a position similar to the Pharisaic brothers. This meeting in Jerusalem appears to be the catalyst for formalizing a conviction that the Jerusalem leadership already holds, but that significantly challenges the Jewish believers who belong to the Pharisaic party.

The term translated “make it difficult” (parenochleō) is a strong, colorful, and somewhat pejorative term only appearing here in the New Testament. It is used in the Old Testament to describe what the lions could have done to Daniel (Dan. 6:19, 24 LXX) and to portray Delilah’s nagging of Sampson (Judg. 16:16).

Telling them to abstain from (15:20). The focus of the debate now shifts away from the question of what is essential for salvation to one of how to help Gentile believers break away from their idolatrous pre-Christian practices. Each of these four instructions relates to dangers associated with involvement in idolatry. James wants to make sure that these Gentiles make a clean break with their past when they embrace the living and true God. The instructions are, therefore, guidelines to assist their growth as believers, knowing full well that the Gentiles will continue to face significant cultural and spiritual pressures stemming from their past immersion in idolatry and ongoing association with family, friends, and coworkers still involved with it. These guidelines are a practical help in the spiritual and moral battle these Gentiles will face.

Later, in a similar vein, Peter wrote a letter to Gentiles in the northern portion of Asia Minor, encouraging them to abstain from certain practices: “Dear friends, I urge you, as aliens and strangers in the world, to abstain from sinful desires, which war against your soul” (1 Peter 2:11). The apostle John abruptly ended his first letter with the warning, “Dear children, keep yourselves from idols” (1 John 5:21).

It is important that we do not view the so-called “Apostolic Decree” as a compromising effort of the Jewish leaders to get the Gentiles to obey at least some of the Jewish law. The decree is not at all a matter of law-obedience for the sake of obtaining salvation. Nor is the decree a concession to the law-oriented consciences of Jews who want the Gentiles to meet them halfway as a means of expressing cultural sensitivity and thereby promoting unified table fellowship. The latter view cannot explain why these four specific prohibitions are selected as opposed to others. In other words, why didn’t the council restrict Gentiles from eating pork in the presence of Jewish believers?

Food polluted by idols (15:20). The Greek word alisgēma should not be limited to food, but should be understood as referring to any kind of contact with idolatrous practices. The church father Gregory of Nyssa describes well what James is referring to: “The pollution around the idols, the disgusting smell and smoke of sacrifices, the defiling gore about the altars, and the taint of blood from the offerings.”295 In his revelation on Sinai, the Lord explicitly prohibited the worship of other gods in the first two of the Ten Commandments (Ex. 20:2–6) and forbade offering sacrifices to idols (Lev. 17:7). This is one aspect of the law that is never repealed.

AN IDOL

Statue of the goddess Aphrodite.

From sexual immorality (15:20). The term porneia is used in Judaism to refer to any kind of sexual activity outside the bond of marriage.296 Porneia is roundly condemned throughout the New Testament.297 The sexual mores of the Greek and Roman world were much more lax than what was expected and practiced in Judaism and early Christianity. This was certainly one area where new Gentile believers needed admonishment. But illicit sexual activity also occurred in connection with the worship of other gods.298 Growing as a disciple of Christ meant leaving the sensual delights associated with idolatry.

From the meat of strangled animals and from blood (15:20). These prohibitions are often interpreted in light of Leviticus 17:10–16. In this context, both Israelites and resident Gentile aliens were commanded not to eat blood or any animal from which the blood had not been drained. But this view does not do justice to the precise wording of this text.

“The meat of strangled animals” is an interpretive translation of the Greek word pnikton, which simply means “choked” or “strangled.” The term neither appears in Leviticus 17 nor anywhere else in the Old Testament, but is known and used in connection with pagan idolatry.299 Both Jews and the early Christians are convinced that demonic spirits were involved in idolatry. When writing to the Corinthians, the apostle Paul wrote, “The sacrifices of pagans are offered to demons, not to God, and I do not want you to be participants with demons” (1 Cor. 10:20). In commenting on this passage, the church father Origen observes that demons especially like blood and sacrificial animals that have been strangled:

As to things strangled, we are forbidden by Scripture to partake of them, because the blood is still in them; and blood, especially the odour arising from blood, is said to be the food of demons. Perhaps, then, if we were to eat of strangled animals, we might have such spirits feeding along with us.300

Similarly, Basil the Great, explains how demons savor the smell of burning blood from the burnt offering of a strangled animal:

The demon sits in the idol, to which sacrifices are brought, and partakes of a part of the blood that has evaporated into the air as well as of the steam rising from the fat and from the rest of the burnt-offering.301

The so-called decree from the Jerusalem church may, therefore, best be understood as a set of guidelines to protect new Gentile believers from the many dangers of idolatry.302 The intent of these latter two prohibitions may help these Gentile believers avoid demonic influence that could arise after consuming sacrificial food.

For Moses has been preached in every city from the earliest times (15:21). James concludes his address by pointing out that the law of Moses is read in the synagogues on a regular basis in all the cities of the Mediterranean world where there are Jewish communities, which is certainly all major cities. Philo observes that “each seventh day there stand wide open in every city thousands of schools [viz., synagogues]” where anyone can come and hear the law of Moses being taught.303

The literal translation of this clause is, “Moses has those who are preaching him.” Perhaps James concludes in this way to provide a contrast: There will continue to be those who proclaim Moses in the synagogues throughout the empire, burdening the Gentiles with the requirements of the law for salvation (Acts 15:19), but we will preach a message of grace based on faith in the work of Christ (15:11). James is not trying to reassure the Pharisaic Christians that the Gentile converts will learn the law of Moses in all of their respective cities. This wrongly assumes that these Gentiles will be attending the synagogue services every Sabbath.

They chose Judas (called Barsabbas) (15:22). What Peter and James say appears to gain the consensus of the Jerusalem church. They then choose two representatives from the church to travel to Antioch with Paul and Barnabas to communicate to the Gentile believers what has happened in the proceedings and to pass on the letter. Of Judas, also called Barsabbas (as was Joseph in 1:23), nothing else is known in the New Testament or later church history.

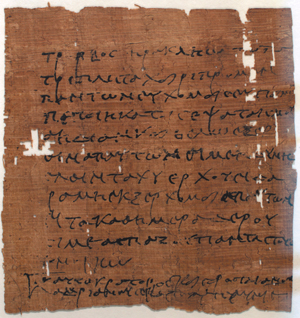

PAPYRUS LETTER

Silas (15:22). Silas is the shortened form of the name “Silvanus.” He is here identified as a leader (hēgoumenos) in the Jerusalem church, which probably implies that he was an “elder” (presbyteros). It is not known whether he was from a Pharisaic background. Paul gains a great deal of confidence in this leader as they spend time together in Jerusalem and Antioch. Silas becomes a fellow missionary with Paul and helps to plant the churches in Philippi, Thessalonica, and Corinth (see the references to him in 16:19–18:5). He is mentioned by Paul in three of the letters.304 He is not mentioned again after Paul leaves Corinth for Ephesus and then Jerusalem (unless the “Silas” Peter refers to in 1 Peter 5:12 is the same person). Luke comes into contact with Silas at Troas and journeys with the team to Philippi (see Acts 16:10–12). Silas may have been an important source of information for Luke about the early years of the Jerusalem church and the Jerusalem Council.

Some went out from us without our authorization and disturbed you (15:24). Luke now reveals that “the men who came down from Judea to Antioch” did so without the blessing and approval of the apostles and elders of the Jerusalem church. Some interpreters suggest that the Jerusalem church sent them on a “fact-finding” mission, but that they drastically overstepped their authority by insisting on circumcision and law observance.305 The arrival of this law-oriented delegation in Antioch corresponds with the arrival of a similar delegation in the churches of Galatia (Gal. 1:7). Both had the same disruptive impact.

It seemed good to the Holy Spirit (15:28). There was a widespread conviction among the leaders of the Jerusalem church that the Holy Spirit led them in making these decisions. Given the gravity of this decision and its implications for the future direction of the church, it is especially significant to have this unanimity on discerning how the Spirit is directing them.

The Church at Antioch Receives the News (15:30–33)

They gathered the church together and delivered the letter (15:30). Letters are typically read aloud to groups in antiquity. They are not duplicated and distributed.

Glad for its encouraging message (15:31). Their worst fears—that the Pharisaic Christian delegation represent the convictions of the Jerusalem congregation—are alleviated. The Gentile Christians in Antioch now rejoice in a reaffirmation of the genuine unity with the Jerusalem church. They are probably also encouraged by the letter giving wise guidance to stimulate their growth in the faith.

Who themselves were prophets, said much to encourage and strengthen the brothers (15:32). Luke now informs us that Judas and Silas are prophets. Although Christians often think of prophecy primarily in terms of revelatory insight into future events, there is a strong edificatory function in prophecy, as exhibited here (see 1 Cor. 14:3).

Paul Returns to South Galatia (15:36–40)

Let us go back and visit the brothers in all the towns (15:36). Paul’s proposal to Barnabas is to return and visit all of the new believers from their recent trip across the island of Cyprus as well as Antioch, Iconium, Lystra, and Derbe in the southern part of the Roman province of Galatia.

They had such a sharp disagreement that they parted company (15:39). Apparently Paul is still upset about John Mark’s sudden departure during their initial journey to Asia Minor (see 13:13). He does not see John Mark as a suitable coworker for the kind of rigorous mission work they will be engaging in. The word translated “sharp disagreement” (paroxysmos) is a rare and colorful word. It is used only twice in the Greek Old Testament—in both instances to express “the furious anger” of God.306 Whatever it is that so exasperated Paul about John Mark was overcome in the next few years and the two are completely reconciled. He was with Paul ten years later during his Roman imprisonment (Col. 4:10; Philem. 24), and Paul asked for him during his subsequent imprisonment in terms expressing his high esteem: “Get Mark and bring him with you, because he is helpful to me in my ministry” (2 Tim. 4:11).

Barnabas took Mark and sailed for Cyprus (15:39). Accompanied by Mark, Barnabas returns to his native island to continue the evangelization of the cities and villages that he began with Paul. This is the last that we hear of Barnabas in the biblical record.

Paul chose Silas and left (15:40). Not wanting to travel alone and aware of the significant giftedness of Silas, Paul contacts him (he is presumably still in Jerusalem) and asks him to be his coworker in the mission. Because of Silas’s prominent role as a leader in the Jerusalem church, he is an important voice for the churches in Galatia disturbed by the Pharisaic Christians insisting on circumcision and law observance.

ANTIOCH OF SYRIA TO SOUTH GALATIA

He went through Syria and Cilicia (15:40). Rather than taking a boat from Seleucia to Attalia, Paul decides to take an overland route. This enables him to visit and encourage churches that he and others had previously established in these regions, including his hometown of Tarsus (see 9:30; 11:25). This rugged route takes him through a narrow mountainous pass called the “Cilician Gates.”