Paul Stands Trial Before Festus (25:1–12)

With the change of procurators comes a resumption of Paul’s trial. Any hope of a dismissal under Felix evaporates with his recall by the emperor. As soon as Festus arrives on the scene (A.D. 59), the Jerusalem leaders exploit the situation to seek an extradition of Paul to Jerusalem. This does not work and a hearing is convened in Caesarea.

AERIAL VIEW OF CAESAREA

The theater is visible in the top right. The remains of the hippodrome are in the foreground.

Festus went up from Caesarea to Jerusalem (25:1). Shortly after assuming his new position, Festus travels to the principal city of his domain to become acquainted with the religious and political leaders. As an outsider, he has much to learn about this volatile region.

The chief priests and Jewish leaders appeared before him (25:2). “Chief priests” refers to the current high priest, former high priests, and the priestly group from whom the high priests are chosen. The high priest is now Ishmael ben Phiabi. After he takes office, a terrible schism arises between the ruling elite and the chief priests, resulting in violence.488 The two groups are united, however, in their opposition to Paul and the Jesus movement. The fact that Paul’s case is one of the first items they discuss with the new Roman procurator demonstrates the importance of the case to them.

As a favor to them (25:3). The Jewish leaders quickly attempt to take advantage of the new procurator’s natural tendency to ingratiate himself to them. For maintaining security in this region, Festus would certainly want to achieve their goodwill. This is especially important in the aftermath of the Jew-Gentile rioting in Caesarea that led to the demise of his predecessor Felix.489 The case of Paul—a person with whom he has no prior familiarity—would be a matter of indifference to him. Although it is his duty to uphold Roman law, the rulers of the eastern provinces frequently bent the law to obtain their desired political aims.

They were preparing an ambush (25:3). Luke does not state specifically who is preparing the ambush. Presumably, the forty men who previously took the vow would still want to carry it out (23:13–14). Others also may have joined them in their strategy to rid the Holy Land of the outspoken man they consider to be perverting the law. The plan now is to ambush Paul somewhere on the road from Caesarea to Jerusalem. As with the previous strategy, they would not be able to accomplish their aim without some Roman casualties.

He convened the court (25:6). Festus reopens Paul’s case by inviting leaders from Jerusalem to travel to Caesarea and present their charges against him. This time there is no mention of a hired rhetorician/lawyer to represent the Jerusalem side. They apparently raise the same charges, accusing Paul of abandoning the Jewish law and defiling the temple.

I have done nothing wrong … against Caesar (25:8). In his defense, Paul implies that the Jewish leaders are accusing him of sedition. In a Roman context, this was a serious charge, which could lead to death. It may be an expansion of Tertullus’s charge that Paul was a “troublemaker” (see 24:15). The charge may be based on reports that the priests have heard from Diaspora Jews in places such as Thessalonica (17:6–7), where Paul had run-ins with the Roman authorities.

Festus, wishing to do the Jews a favor (25:9). Luke recognizes that politics has now entered into the trial and that any notion of fair and just proceedings is hopeless.

Are you willing to go to Jerusalem and stand trial (25:9). Festus now changes his mind and reveals an openness to change the venue of the trial to Jerusalem. It may seem odd to us that a Roman ruler would ask his prisoner about his willingness to stand trial in a different city, but as a Roman citizen, Paul has the right to insist on a Roman trial.490 It is unclear what Festus has in mind: Is he proposing that Paul stand trial in the Sanhedrin and he would be present and merely approve the outcome of their deliberations? Or is he planning to hold the trial in the Antonia Fortress in the presence of the Jerusalem leaders?

I appeal to Caesar (25:11). As a Roman citizen, Paul has the right to make an appeal to have his case heard in Rome by the emperor. There were varied forms of this provision giving citizens the right to appeal at any point during the course of legal action or after a verdict had been rendered.491 Paul’s case has been in limbo for two years and now seems to be moving in a disadvantageous direction. To prevent his case from being moved to Jerusalem, Paul asserts his right of appeal (provocatio) at this time. Why he had not done so previously can only be explained on the basis that he assumed the charges against him would eventually be dismissed, whereupon he could travel to Rome (according to his plans) as a free man.

Paul has seen enough to convince him that he will not receive a fair trial in Jerusalem. Because of his nephew’s previous warning and the antipathy of the Jewish leaders against him, perhaps he is also suspicious of the very thing that they are plotting against him. The apostle is clearly not fearful of suffering for the sake of Christ—even to the point of death. Yet the overriding concerns of the gospel drive him to use the means available to him to forestall an extradition to Jerusalem so he can travel to Rome and present his case to the emperor himself. The appeal will give him an unprecedented opportunity for presenting the gospel at the highest seat of Roman power. Perhaps Paul now sees his right of appeal as the way the Lord has given him for getting to Rome to testify before the authorities (see 23:11).

Paul will be making his appeal to appear before Nero, who has been emperor for five years by A.D. 59. At this point in Nero’s principate, he showed a fair amount of stability as he was still under the influence of his tutor, Seneca (the Stoic philosopher) and Sextus Afrianus Burrus. The horrible atrocities against Christians will take place five years hence after the burning of Rome (A.D. 64).

After Festus had conferred with his council (25:12). Festus has the power to deny Paul’s request if it is not reasonable or falls within a list of exceptions.492 Of course, he has the option of dismissing the charges altogether, though the latter course of action is not in the interest of maintaining order among the Jews. To help him make a decision, Festus meets with his own council—a panel of eight to twenty local Roman citizens, military men, and civil servants who function as an advisory group on judicial matters.493

Paul Appears Before Agrippa (25:13–27)

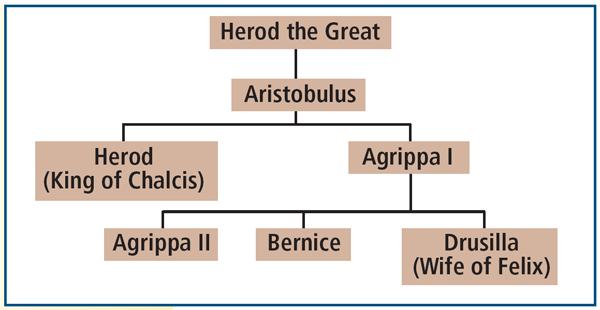

After Paul makes his appeal to the emperor, he must wait for the procurator to write an accompanying report about the case. During this time, the client-king from the northern territories (which includes a portion of the area of modern Lebanon) comes to welcome the new procurator. This king is the grandson of Herod the Great, a valued friend of Rome, knowledgeable about the affairs of the Jews, curator of the temple, and someone in charge of appointing high priests in Jerusalem. If anyone could legally lay claim to the title “king of the Jews,” it is Agrippa. For Festus, his arrival presents a fortuitous opportunity to gain additional perspective on the case. Since Agrippa possesses no legal jurisdiction in Judea, the hearing should be regarded as merely an informal inquiry into Paul’s case.

Bernice (25:13). Bernice was the younger sister—not the wife—of Agrippa.494 Yet suspicions abounded that there was an inappropriate relationship between the two.495 At the time of this hearing with Paul, she and her brother would have been thirty-one and thirty-two years of age.

COIN WITH THE IMAGE OF HEROD AGRIPPA II

Bernice was previously married to Marcus Julius Alexander (in A.D. 41), who died shortly afterward, and to her uncle, Herod of Chalcis (whose kingdom Agrippa inherited), who died in A.D. 48. She and her two children from Herod lived with Agrippa for the next fifteen years. It was during this time that rumors circulated that she was having an incestuous relationship with her brother. To thwart the evil gossip, she married King Polemon of Cilicia in A.D. 64 (about five years after the hearing with Paul), but this marriage did not last and she returned to her brother. She later fell in love with Titus, the Roman general who destroyed Jerusalem, and became his mistress. She went to Rome in A.D. 75 and lived with him on the Palatine, but popular sentiment forced Titus to terminate this liason.

She was in Jerusalem at the outbreak of the Jewish war and interceded on behalf of the Jews to the Roman procurator, Gessius Florus (A.D. 64–66), with substantial risk to her own life. She and her brother also made repeated efforts to dissuade the Jewish revolutionaries, but were not successful.

To pay their respects to Festus (25:13). The couple comes to Caesarea to meet the new procurator of Judea. They have a vested interest in Judea and certainly want to secure the new procurator’s goodwill.

Festus discussed Paul’s case with the king (25:14). This is the perfect opportunity for Festus to discuss Paul’s case with someone far more knowledgeable about Jewish affairs than he is. In the next eight verses, Luke summarizes Festus’s presentation of the case to Agrippa. How Luke knows what is said in this private discussion is difficult to discern unless he has access to informants who were present and heard what was said.496 It is also possible that Luke is merely inferring what is said based on what is widely known about the case.497

Before he has faced his accusers (25:16). It was an established Roman custom acknowledged as law that the plaintiffs had to make their accusations before a judge in the presence of the defendant: “This is the law by which we abide: No one may be condemned in his [the plaintiff’s] absence, nor can equity tolerate that anyone be condemned without his case being heard.”498 Similarly, Appian states, “The law requires, members of the council, that a man who is on trial should hear the accusation and speak in his own defense before judgment is passed on him.”499

About their own religion (25:19). This is not the common Greek word for “religion,” but a term (deisidaimonia) often translated “superstition” and can mean “a terrible fear of the gods” or “dread of demons.” Although it could be used in a positive sense (“reverence for the gods,” as in 17:22), Festus is here being derogatory in his comments about Christianity.

A dead man named Jesus who Paul claimed was alive (25:19). Previously, in his hearing before Felix, Luke records Paul as stating that he is on trial because of his belief in the resurrection of the dead (24:21). Now we know that Paul specifically relates his belief in the resurrection to one particular person whom he believes God has already raised—Jesus of Nazareth.

For the Emperor’s decision (25:21). The term here used for emperor is Sebastos, the Greek equivalent of the Latin Augustus. The word itself means “revered” or “worthy of reverence.” It is a title that the Roman Senate first conferred on Gaius Octavius (Caesar Augustus) and was subsequently used for his successors.

Agrippa and Bernice came with great pomp (25:23). “Pomp” is the NIV’s translation of the Greek word phantasia, a word used in Aristotle for the faculty of the imagination.500 Here it refers to an ostentatious display that sometimes accompanies the arrival and procession of a king.

With the high ranking officers and leading men of the city (25:23). The high ranking officers are literally, chiliarchos, the commanders of the cohorts in the city (the same rank as Claudius Lysias in Jerusalem). According to Josephus, five cohorts were stationed at Caesarea.501 In addition to the military officers, all the leading civic officials were also present. The apostle Paul would have the chance to address an elite gathering. This continues to fulfill the words of Jesus, who predicted regarding his witnesses: “They will lay hands on you and persecute you. They will deliver you to synagogues and prisons, and you will be brought before kings and governors, and all on account of my name” (Luke 22:12).

The whole Jewish community has petitioned me (25:24). This does not refer to every Jew living in Judea, but rather the legal representatives of the nation, namely, the Sanhedrin and the chief priests.

His Majesty (25:26). Literally, “my Lord [kyrios].” The Roman emperors were also referred to by the title “Lord.” This was especially true in the eastern Mediterranean region. Egyptian papyri have been discovered where the title kyrios is applied to Augustus (P.Oxy. 1143.4), Claudius (P.Oxy. 37.6), and Nero (P.Oxy. 246.30, 34, 37). As one scholar puts it: “The title denoted the status and power that the Princeps enjoyed in the Roman world.”502

As a result of this investigation I may have something to write (25:26). Festus is still at a loss on how to present Paul’s case to the emperor. Convinced that Paul is not guilty of sedition against the emperor, he is hopeful that this informal hearing will clarify the issues so that he can write a competent report. Roman law required such a report from Festus: “After an appeal has been made, records must be provided by the one with whom the appeal has been filed to the person who will adjudicate the appeal.”503