In his essay on Gide, Pamuk, the only Turkish citizen to win the Nobel Prize for Literature, begins with a meditation on the veneration with which Turkish intellectuals “admired Gide, especially those who looked to Paris with reverence and longing.” Gide, was viewed as a consummate literary mind, and with his Journal, a beacon of self-reflection that spawned a small industry from later writers in the confessional genre and the memoir. Gide, who was also an avid traveler, recounts his visit to Istanbul with unerring distaste, finding it a mish-mash of tastes and thus culturally superficial, insincere. Pamuk quotes Gide: “Nothing sprang from the soil itself, nothing indigenous underlies the thick froth made by the friction and clash of so many races, histories, beliefs and civilizations.” His harshest criticism is aimed at Turkish dress: “The Turkish costume is the ugliest you can imagine, and the race, to tell the truth, deserves it.” He declares his inability to hold affection for a country when so out of sympathy with its people.1

Pamuk concludes his essay with Atatürk’s dress reforms two years after he established the Republic in 1923. He cites a comment by Atatürk regarding the aimless heterogeneity of the national clothing, for example mixing a fez coupled with a turban, and a mintan, or collarless shirt under a Western style suit jacket. Atatürk exclaims, “Would a civilized person let the world hold him up to ridicule by dressing so strangely?”2 Pamuk asks whether Atatürk and Gide shared similar views on “dress as a measure of civilization”3 whereupon he quotes Gide again: “When the citizens of the Turkish Republic declare that they are civilized, they are obliged to prove that they are so through their family life and their lifestyle. A costume which, if you excuse the expression, is half flute, half rifle barrel is neither national nor international.”4 Pamuk remarks that the tensions relating to dress continue in his day, with police “still chasing people going about the conservative neighborhoods of Istanbul in traditional dress.”5 He notes a “shame” at the Westernizer’s alienation from Europe, in the recognition of always being incomplete, marginalized, and inadequate. “He is ashamed of who he is and who he is not. He is ashamed of the shame itself; sometimes he rails against it and sometimes he accepts it with resignation.”6 Pamuk is not necessarily holding anyone or anything to account, since in retrospect it is easy to argue that Turkey’s modernization was inevitable, although painful—although this is a belief that has also been perennially challenged. Both geographically and ideologically, both truly and mythically, Turkey stands at the juncture between East and West. It provides what is most likely a unique case in modern times of the mixture of cultures. Significantly these changes were brokered most conspicuously along the lines of fashion and dress.

What Turkish and Chinese Orientalist styling had in common were the connotations of despotism. Always conceived in the abstract, despotism proved fertile ground for other notions to grow, for absolute authority also suggested the satisfaction of hidden and forbidden desire. Turkey and turquerie were always redolent with the scent of the harem, the imaginative epicenter of the (male) Orientalist imagination: sexual, forbidden, and foreign. It is worth briefly revisiting the more traditional notions of Turkey and Orientalism, as it helps to anchor the issues, active to the present day, of Turkey’s de-Orientalizing. Most present are the many conflicting opinions about the veil, arguably the most loaded symbol of gender relations, enshrining notions of propriety, honor, and desire. As a signifier of gender difference (and for detractors gross inequality), it is also one of the key signifiers of Turkey’s difference from the West.

An early literary example of the way in which the erotic is played out through Turkish dress appears in Daniel Defoe’s Roxana, published in 1724. It is the story of the rise and fall of a courtesan, involving scenes of mild pornography to grisly episodes where she murders her own child. One of the novel’s central scenes involves two performances that Roxana makes for the court of Charles II in Turkish costume in order to seduce the King and become his mistress. Maximillian Novak remarks that these dances in Turkish costume bring to the fore some of the novel’s key points of commentary: “the sexual immorality of the Restoration and with it the comparison with contemporary morality; and the attack on disguise and deception.”7 In retrospect, Turkish costume is the only choice to be made since it is a masquerade in which erotic implications are writ large. The most lasting equivalent in music, no doubt, is Mozart’s Entführung aus dem Serail (1782).

The instances of Ottoman Orientalism in painting are too many to enumerate, but suffice a few examples. In America, John Singleton Copley made a series of portraits of both men and women wearing turquerie. In her examination of his portraits of women before the American Revolution, Isabel Breskin contends that Oriental costuming was used as a means of expressing a particular colonial identity. For while turquerie fashions were well-established in Britain, they could also be used to register colonial difference. In the climate of “emulation and rebellion” in this time of America’s history, dressing up in turquerie afforded a displacement of the consciousness of an inferior position. For while the women in turquerie could easily be read as “the subjugated colonial,” the clothing also allows the expression of “a note of defiance.” “These women are, for this self-created moment, among the ‘only free people in the empire’.”8 As with the popular masquerade that flourished in the eighteenth century, other cultures were used with disregard for authenticity. They served as aesthetic and ideological vehicles for self-expression at all levels, from genteel to sexual.

The adoption of Turkish costume has a long history in Western culture, particularly in the imperial states of Britain and France. A very early reported example is that in the 1530s Henry VIII wore Turkish costume to a masquerade ball. Masquerades were a significant part of courtly life across Europe until the end of the eighteenth century. In 1714, the French ambassador to Istanbul, the Marquis de Ferriol, published an album of images of people in Ottoman dress, derived from the Dutch painter, Jean Baptiste Vanmour. In England, in 1757, Thomas Jeffrey published what would be a celebrated album for masquerade adaptations, his Collection of the Dresses of Different Nations, where Ottoman dress was handsomely represented.9

But the taste for Ottoman clothing did not stop at masquerade, for it served a more socio-political function. The writings of Lady Mary Wortley Montagu, about her experiences of her brief stay in Istanbul between 1716 and 1718 while accompanying her husband as the British ambassador to the Ottoman Empire, had a singular and widespread effect on the women of her time. This had largely to do with, in the words of Onur Inal, “Ottoman women’s rights over their husbands, such as the right to refuse conjugal sex, to own property, to enter into contracts, or to divorce their spouses.”10 It was knowledge afforded by the expanding image of the world precipitated by imperialism. “These rights came to be symbolized by Ottoman women’s dress, especially by salvar, a voluminous undergarment in white fabric shaped like what are called today ‘harem pants’.”11 In order to assimilate, Montagu dressed as other Ottoman women while abroad, then continued the practice back in England, something that not only added to her exotic pre-eminence but was also taken as support for the burgeoning British women’s movement. Her Embassy Letters (1763) continued to have influence well after death. A significant figure in Montagu’s wake was Elizabeth Craven, whose A Journey through the Crimea to Constantinople (1789) again fed the fascination for the harem, which she discussed not from the male erotic viewpoint but as a privileged female space where women have numerous freedoms not available to European women. She was followed by a number of women in the nineteenth century who journeyed to the Ottoman Empire, brought back clothes and artifacts, and corrected Orientalist clichés and misprisions.12 Notable women such as Lady Archibald Campbell and Ottoline Morrell wore the salvar to register their impatience with traditional British values. The salvar enjoyed a robust life and ultimately transformed into the bloomer—named after Jenks Bloomer—the garment of women’s suffrage. The Orientalist view of Ottoman women as retiring and passive needs correction, especially when considering the significant place that their mores and dress had for the growth of modern female identity in Europe.13

This short itinerary adumbrating the many subtleties of the reception of Turkey to the Western imagination, and its role in the shaping of modern womanhood, will prove a counterpoint to the convoluted and shifting history women’s dress, particularly the scarf, that unfolded in the twentieth century.

Except for clichés and their own unlicensed appropriations of it, contemporary Westerners do not have a particularly comprehensive knowledge of Turkey, as with any country that is not dominant or a symbol of aspiration. At best, Euro-American understanding of Turkey is as a country that straddles East and West both geographically and culturally, that has long sought inclusion into the ailing European Union, the reasons for which vary according to whom you consult. From the Euro-American perspective, it may come as some surprise that Turkey’s desire for inclusion is less economic than it is symbolic. Ever since its citizens were mandated to wear European clothing and were instructed to look Westward rather than Eastward, Turkey became a country that craved European approval, only to have felt its cold indifference. Even though it had never been a colonized state, the condescension Turkey felt from the West had a colonialist air. After numerous attempts to join, the continual rebuff from the European Community has been decisive in consigning Turkey to cultural limbo. For it is recognized as neither Western nor Arab: its dress is predominately Western, and its script is Roman. It does nonetheless suffer from internal pressures of its various Muslim groups, who are hostile to those who embrace the “decadent” West, as evidenced in recent times when in late 2016 a gunman let loose in an exclusive nightclub in the Westernized district of Bes¸iktas¸. Turkey is a country in which notions of difference and ambivalence—in history, religion, appearance, and so much more—lie at the center of its identity. While Turkey, and its largest city, Istanbul, formerly known as Constantinople, have always been a crossroads of cultures, it maintained coherence all the while it had military strength and strong governance, with the Ottoman Empire that began its rise in the thirteenth century. It reached its apogee with the reign of Suleiman the Magnificent (who reigned 1520–1566) and began its decline at the end of the seventeenth century. By the nineteenth century the Ottoman Empire had considerably constricted and was socially and financially devastated by the brutal Crimean War (1853–1856).

Modern Turkey is a product of the First World War, which left the once proud Ottoman state in ruins. The cause of the disastrous result of the War was widely held to be backwardness of the country. Its clinging to anachronistic ritual and ideas had severely slowed the rate of progress. As the effects of the War showed, if the stagnation could not be addressed, it would end in the dissolution of the state altogether. In 1920 under the Treaty of Sèvres, Sultan Mehmed VI was forced to cede vast sections of his territory to Britain, France, Greece, and Armenia. Henceforth known as the “Sèvres Syndrome,” Turkish citizens became beset with the fear that their country would disappear altogether, much as the Treaty of a Trianon had done to Austria and Hungary. With the Turkish War of Independence (1919–1922), led by Mustafa Kemal (later Atatürk), the treaty was challenged and replaced by the Lausanne Treaty (1923), which laid the boundaries of the Turkey known to this day.

While traditionally the outside “Orientalizing” Western vision has and continues to typecast the Ottoman and the Turk as all one Muslim race, the reality is quite different, mirroring more the diversity of cultures of the Austro–Hungarian Empire before its collapse at the end of the First World War. Historically the “core” of the Ottoman Empire, roughly what Turkey is today, was the refuge for Muslim peoples, including those banished or fleeing persecution. For instance, when Russia invaded the North Sea in 1774, thousands of Crimean Tatars migrated to Anatolia. They were followed by the Muslims from the northern Caucasus, also driven out by the Russians. From the 1860s onward, Circassians from the Abkhaz to the Chechens were driven into the Ottoman Empire. In 1877, Austria’s annexation of Bosnia-Herzegovina resulted in an influx of tens of thousands of Muslim refugees. The Balkan Wars of 1912–1913, while causing the Ottoman Empire’s age-old territories over Albania, Bulgaria, Greece, Kosovo, Macedonia, and Romania, also resulted in the immigration of innumerable Muslims. And under the Lausanne Treaty many Muslim Turks in Greece and Greek Orthodox citizens of Turkey effectively traded places. Up until today, Turkey’s ethnic minorities have an acute sense of their local identity, a sense that tends to be sharpened when threatened from other groups or socio-economic upheaval and strain. Added to all of this, in the nineteenth century until at least the First World War, Turkey was in deep sympathy with large portions of Hungarian community disaffected with Austrian supremacy. These sympathies were strong enough to provoke philological, historical, and ideological debates into the Turkic origins of the Hungarian peoples and their language.14

Atatürk understood the need to integrate Turkey’s many ethnic groups and at the same time to try to bring the country on better par with the more prosperous European nations. As Kezer puts it: “Having internalized Orientalist criticisms of the Ottoman state and culture, they sought to introduce Westernizing reforms that would affect day-to-day lives of the citizenry on an unprecedented scale.”15 Known later as Kemalism, his program consisted of six “arrows” or trajectories, areas of focus to ground the new modern state: nationalism, populism, republicanism, revolutionism, secularism, and statism. After the adoption of the Constitution in 1924, Atatürk embarked on a series of swift, stark, and dramatic reforms, including the abandonment of the Arabic script for the Latin, and shifting the capital from Istanbul to Ankara. Relocating the capital Atatürk saw as an important symbolic gesture to distance the new modern state from the historic seat of the caliphate. “Authentic” Turkish identity would be the sum of many newly assumed parts. Not only was the fez outlawed, but wearing anything that resembled Muslim dress was strongly discouraged. All outward signs of religious orders were made to seem retrograde and reactionary. One of the most salutary measures was to grant female suffrage and to allow women to be elected as representatives of Parliament.

Since the Turkish republic had come into being as a result of the War of Independence, the military had always played a significant role in the new regime, and Atatürk had devoted as much energy to transforming the military as he had to civil society. The military’s devotion to Atatürk meant that it saw itself as responsible for preserving his legacy, resulting in the military coups of 1960, 1971, and 1980. It was also involved in the coups of 1997 and 2002.

In addition to the military, religion continued to maintain a strong hold on Turkish society. Along with the dress reforms in the early 1920s, religious schools had been closed as had Sufi religious orders. Yet the changes came a little too swiftly, and many members of Turkish society clung to religion as a way of staying the uncertainty of change. In the words of Lenore Martin, “Many citizens remained wedded to Sunni Islam and a conservative mindset. They kept forming political parties, though the courts continued to outlaw them, claiming they were undermining the secular nature of the state and therefore unconstitutional.”16 These struggles would continue to haunt Turkish politics and society, until the AKP, formed from a previously legally disbanded Islamist Party, achieved a parliamentary majority in 2002, going on to win two more elections in 2007 and 2011.

Since the noticeable decline of the Ottoman Empire by the mid-nineteenth century, religion played a central role in determining differences form the West. Ussama Makdisi uses the phrase “Ottoman Orientalism” to designate the complex nature of Ottoman reform that, while turned to the West as an antidote to its perceived backwardness, nonetheless sought to retain national autonomy. “Just as European Orientalism was based on an opposition between Christian West and the Islamic Orient, the Ottomans believed that there were some essential differences that distinguished them from the West—especially a notion of Islam.”17 Reformers sought to address the West’s misinterpretations of the East, with Islam as its linchpin, while also accommodating secularist views. Reform entailed what Makdisi calls a “double movement,” which entailed moving toward European modernity while drawing away from the prejudices of Oriental stagnation and indolence.18 This meant emphasizing parts of its history that countered such notions. In effect, the redrawing of history meant that Turkey was undertaking its own Orientalizing, since it was embedded in what set it apart from the West. He concludes: “Ultimately, both Western and non-Western Orientalisms presuppose a static and essential opposition between East and West; yet both are produced by—and are an attempt to overcome—a crisis in this static opposition created by the same dynamic colonial encounter.”19 This cultural brokering of emulation, while remaining faithful to the past, would prove to have lasting consequences simply because what exactly constituted this difference, and to what one should remain faithful, were very much at the mercy of differing points of view.

Laws governing dress had long been used as in the Ottoman Empire as a way of controlling and homogenizing its various people. “The importance of clothing laws,” aptly states Hale Yilmaz,

lies in the fact that they are never simply about the clothes the subjects or the citizens wear, but rather they are reflections of the broader cultural, political, social, or economic concerns and changes. They serve as “instruments of negotiation” between states and ethnic, religious, or other communities, between élites and other social classes. Their enforcement, social meanings, and eventual success or failure are not determined by the state alone but are shaped in large part through these negotiations.20

Inevitably, such reforms were received in different ways according to the social group. Class, religion, and the divisions between urban and rural life all had their part to play, to the extent that dress laws tended to amplify and deepen such divisions.

Under the sultanate of Mahmud II, in 1827 it was decreed that the fez be the official head covering for the military, and a year later this was extended to all members of the civilian male population. Occurring just before the “Tanzimat,” or reform period, (1839–1876) that began after Mahmud’s death, this measure had a number of intentions. Pre-eminent among them to bring together, in appearance Muslims and non-Muslims, to soften the representations of class, and to make the difference between civilians and government officials less obvious. As Camilla Nereid explains,

Male headgear as an arbiter of identity was a well-established practice, but as the empire declined both economically and militarily, the turban came to be a marker of professional status and independent political power rather than a sign of loyalty to the ruler. As the use of the turban was restricted to the military and the religious classes of the empire, the non-Muslim subjects of the empire were excluded from displaying their loyalty or lack of such towards the Ottoman rule.21

To ensure popular support for these reforms, teachers and religious leaders were enlisted to advance their ardent enthusiasm for the changes. The changes also had to be by higher example. Mahmud was the first sultan to dress noticeably according to European custom, jettisoning his turban, and wearing trousers instead of the traditional loose pants (salvar). But such efforts met with mixed responses, much of them directed at the grounded suspicion that the Sultan was paying lip service to the West through disapproval of traditional dress.

Even if the fez was a compromise over the turban, it was not, however, an item that had been exhumed from the depths of Ottoman history, but rather derived from North Africa. Having been worn for generations in Tunisia, Algeria, India, and Morocco, the fez also had the advantage of expressing fealty with these countries, symbolizing religious and historical bonds. It was an attractive option because of its relatively neutral geometric shape, and because it distinguished itself from Western brimmed hats. Yet in alignment with Western habits, men were expected to keep their beards short and to limit the amount of jewellery. Intended to strengthen the Turkish state, the Tanzimat reforms extended to all strata including the replacement of religious law with secular law, the decriminalization of homosexuality, and the reform of the banking system. The guild system was also dismantled. It was largely the workers who objected to these upheavals, showing their dissent in their refusal to wear the fez.

It did not take long for the fez to meld itself smoothly into the national psyche. Sultan Abdülhamid II (who reigned 1876–1909) regarded the fez as a symbol of tradition that united national and Islamic interests. But while such interests were being defended, there were now several generations that showed their allegiance and indebtedness to Western culture, particularly the French. (Pamuk later recounts how his father fled the family for several years to take up in Paris where he translated several celebrated writers including Paul Valéry. Further, Atatürk was himself highly competent in French and would often speak it with friends.) Indeed, French was a favoured source for creating new words.22 Western manners and customs were all particularly valued as they are today, where to speak the language of an economically prosperous country such as Germany is deemed a sign of intellectual flexibility and international mobility. (By contrast, from the 1970s onward, elite Japanese considered learning French a badge of prestige and good taste.) By the end of the nineteenth century, despite the still current expectation that Turkish men show their national faith in wearing the fez, higher Ottoman officials, particularly diplomats stationed in Europe, began to show their cosmopolitanism by wearing bowler and fedora hats. Within the Empire, non-Muslims were also apt to do so. For gradually the fez had become less a symbol of Ottoman unity and more one of Islam, “thus demonstrating the malleability of cultural constructs” as Nereid concludes.23 The outward trappings of Western appearance announced their difference from Muslim subjects, and by extension, their superiority. It was the signification of this difference, and the potential it had for sowing dissent that culminated in Sultan Abdülhamid banning the European hats in 1877, instating the fez as the hat that men were expected to wear. The reprisals for not doing so were particularly steep, such as termination of employment and even imprisonment for especially government officials.

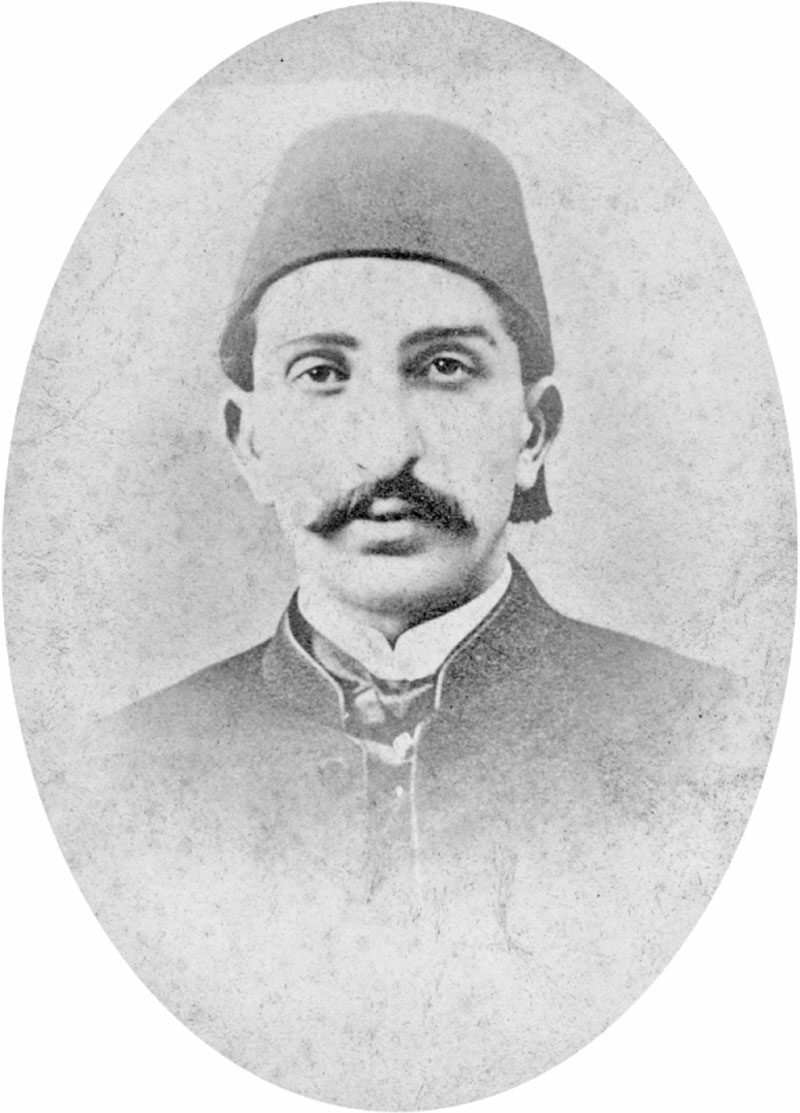

Figure 1 Sultan Abdülhamid (1842–1918). London Stereoscopic & Photographic Co. Printcollector/Gettyimages.

However, as much as the fez may have played an operative role in assuming Turkishness, fezzes were not necessarily all made in Turkey. Austria’s annexation of Bosnia-Herzigovina in 1908 resulted in a boycott of Austrian imports, among them fezzes. The protests, which included destroying fezzes made abroad, renewed discussion of the matter of appropriate headgear and caused alternative ones to be worn such as the kalpak (a high-crowned cap made of felt or sheepskin) and the külah (a cone shaped hat). A year later in 1909 the kalpak was adopted as the official military hat, as it distinguished young officers of War of Liberation from the fez-wearing establishment. The kalpak could have continued to have been the sign of the new Turkey, but the urge to join Europe and to break with the past was too strong. Yet before Mustafa Kemal Atatürk’s Hat Law was promulgated in 1925, Turks after the War continued to wear a variety of different kinds of headgear. In the wars of independence in 1923 the fez was equated with the old regime and, therefore, as Yilmaz observes, “loyalty to the fez must have been weakened in that process.”24 It also helped to internalize the need for change, with clothing playing a cardinal role, “in the sense that clothing changes require changes to one’s established habits.”25 Under Atatürk these habits faced serious threat, and the violence underpinning the changes cannot be underestimated.

For the fez was not only the most prominent sartorial feature for men, but also, because it covered the head, it perforce became the symbol of attitudes and frames of mind. “Old head” was a commonplace Turkish expression for a mentality outdated or left behind, and it was used liberally and interchangeably in relation to hat style. The Hat Law was enacted as part of the overarching Law on the Restoration of Order of March 4, 1925, which gave the government the power to prohibit “all organizations, provocations, exhortations, initiatives and publications which cause disturbance of the social structures.”26 Wearing the wrong hat was precisely one such instance of “provocation” and “disturbance,” as it violated the national campaign for modernization and improvement. As Atatürk himself explained two years after enacting the Hat Law:

It is necessary to abolish the fez, which sat on the heads of our nation as an emblem of ignorance, negligence, fanaticism, and hatred of progress and civilization. To accept in its place the hat, the headgear used by the whole civilized world, and in this way to demonstrate that the Turkish nation, in its mentality as in other respects, in no way diverges from civilized life.27

A remark such as this, laced with its own kind of fanaticism and urgency, helps to understand the rifts the reforms caused in Turkish life. It was also at the heavy price of denigrating the past and by all accounts denigrating the culture as a whole, with the danger of consigning the new face of the country to the status of eternal simulacrum.

Just as the earlier sultanate relied on educators and religious leaders to endorse reforms, Atatürk went to great lengths to ensure that his and his government’s policies were firmly integrated into school curricula. More widely, popular media was also enlisted in refashioning of old ways. A cartoon from March 1924, on the cover of the newspaper Karagöz, still printed in the traditional Arabic script, shows a man on a balcony throwing out a book, an urn, and a skull, reflecting the title “The Disposing of Old Mentalities and Laws.” The skull is the old mentality, the urn refers to the Sèvres vase and thus to foreign occupiers, and the book to otiose dogma. A man in a turban in the background looks on with an expression of consternation. As Yasemin Gencer remarks, “the mullah is thus visually marginalized and symbolically incapacitated. As a result, this cartoon communicates a revolutionary message, pitting Turkishness against Islam, and Western secularism against the ‘antiquarian’ Ottoman-Islamic legal system of shari’a.”28 She argues that cartoons such as these gave the new republic “a second level of visibility that was achieved by rationalizing, promoting, and illustrating what were already very visible social changes.”29

Atatürk’s equation of modernization with secularization and the dismantling of Muslim codes proved to be deeply divisive, for it opposed Kemalist reason with a vision of Islam as a way of life that limited progress. Detractors warned, as Nereid states, that “the construction of a Turkish identity based on superficial Western mimicry was equal to the internalization of inferiority.”30 Further, dress codes created little more than “a masquerade hiding the gap between ideal, Westernized élite of urban Istanbul, and the reality, the poor peasants of rural Turkey.”31 This proved to be irrepressibly true, for the peasantry were by nature less open-minded and less economically disposed to change. Those who could not afford the hat, or were simply disgruntled, wore a cap with a brim on the side or the back. While the extent of resentment at the law is next to impossible to evaluate, as suggested earlier, resentments tended to entrench themselves further with economic hardship. In remote and poor areas, people were also restricted because of lack of money and scarcity of the new “civilized headgear” (“medeni serpus”). Simple caps and other improvised adaptations became the norm in rural areas, causing the government to inform local governors to issue the relevant decrees, whose enforcement was irregular at best. A net effect was not only to emphasize the difference between the urban élite and the poorer provincials, but also to create a Muslim subclass, a Muslim “other,” now judged in the first instance according to appearance. These differences were aggravated further by declarations of the élite that clothing had nothing to do with religion, and therefore to be too fixated on clothing was to reveal the extent of one’s delusion.32 This was not what the common folk wanted to hear after centuries of having been told the opposite.

Unsurprisingly, then, dissent at the Hat Law sparked rioting by people, many of mixed ethnic backgrounds, fearing that the break with the past undermined religious order and, by extension, social and political order. For Islam was seen as the glue between the Kurds and the Turks. The disaffection was so rife in rural areas that it was easy to draw the conclusion that the law was a ploy, or a decoy, to bring the lower echelons of Turkish rural society to heel. As Nereid suggests, “The number of rebellions, arrests, imprisonments, and executions in the aftermath of the Hat Law might lead one to conclude that the rationale behind the hat legislation was to oppress and discipline Turkish society by forcing it to make its resistance visible and thus possible to localize and crush.”33 As she concludes, what the Hat Law disenabled was an essentialist reading of Islam, thereby displacing “essentiality or an origin to which you can return.” In short, “There was no consistent, authentic, original past or traditional ‘other’ hidden by a superficial ‘we’. The traditional ‘other’ was as multifaceted as the modern ‘we’.”34

Although the end of the fez gathered the most attention and incited the most emotion, this did not mean that the changes were limited to it. Rather transformation ramified to all parts of Turkish dress, from top to toe, with facial hair also becoming shorter or disappearing altogether. The campaign to conform to Western canons of dress had many immeasurable consequences. It alienated the rural and working classes whose contact and knowledge of the West was slender to non-existent, and it disrupted age-old traditions of weaving and tailoring. One such item was the karadon, the baggy pants, which in the summer were worn with a sleeveless shirt (aba), which was banned by authorities, polarizing members of the community in areas of both production and consumption.35

Since 9/11 the veil has assumed large, and some would say, disproportionate metonymic significance as a symbol of the difference between the values of the Christian West and the Islamic East. Seen in the most ideological light, it has become a powerful symbol of Islam putative oppression of women, as well as its cultural backwardness, and its tenacious weddedness to the remote past. What is far less known is that veiling, which for all and sundry is the outward symbol bar none of Islam, did not begin with Islam, existing well before the religion originated in the early seventh century, and practiced not only by Muslim women, but by Jewish and Christian women as well.36 It can be traced back to Ancient Mesopotamia (3000 CE), through Ancient Greece and Rome, to the Persian-Sassanid dynasty (224–651 CE) and the Byzantine Empire (306–1453 CE).37

To the modern, liberal, and individualist Western eye, the veil appears to have quite a definite message, namely covering what ought not to be covered, for to deny the face is ostensibly to deny identity and identification. As Sahar Amer, in her detailed study of veiling, gnomically states: “Liberating Muslim women became a leitmotif of nineteenth-century European discussions about Muslim societies, and a key component of what has come to be known as the White Man’s Burden.”38 For the simplistic dualism to veil or not to veil is itself a front for much more varied views and more nuanced circumstances. The Iraqi feminist Basima Bezirgan commented in the mid-1990s that: “Compared to the real issues that are involved between men and women in the Middle East today, the veil itself is unimportant.”39 Yet if it is inconsequential to some, it is for others what divides men and women, and their claims to equality. Huda Sharawi, founder of the Women’s Union in Egypt, removed her veil in 1923 as an expression of her dissatisfaction.40 Nonetheless, as Elizabeth and Robert Fernea point out, veil or no veil, the strictly observed role of women in society and the household in Islamic countries is largely preserved.41 It is a pertinent symbol of female honor, which must also be reciprocated by men who also wish to be known as honorable. Amer concludes that “veiling is not and has never been a neutral phenomenon.” It has always been subject to “competing meanings and motivations at different times and in different places.”42 What is certain is that the veil remains an inflammatory symbol that has had one significant climax in France’s outlawing of the veil in 2010. The guiding premise of the Constitution of the 5th republic was that France is a fundamentally secular state and systems of belief ought not to impinge upon the “community” as a whole.43 As we know, beneath the rhetoric of French liberalism lay many discontinuous strata of pain and resentment in the aftermath of French colonialism, and the Algerian war, a still lingering presence in the minds of many.

It is a controversy that also helps to recall the discomfort that Turkish men experienced with having to forgo the fez, for the divestiture of both was to a great extent an imposed nakedness that exposed the interrelation of self, clothing, national identity, and religion. In both cases clothing and appearance played witness to the defense of a highly abstract invocation of fidelity to the state. One recurring argument for hijab, and the (forced) enclosure of women’s bodies, is that it gave as much room for movement as it was an impediment, inasmuch as women remained anonymous, an invisibility that also had its advantages. It also managed the ability to conceal other forms of dress beneath it. But it was also in the nineteenth century that women began to change their style of clothing, especially indoors, for example moving away from the gömlek and the salvar toward the entari, a long dress that was in tune with the European look.

Concealment and the ambiguities that this engendered helped to nourish the imaginations of generations of artists, writers, and composers. The fetish over the harem is the first narrative port of call, and heavily commented upon, not least in the famous letters of Mary Wortley Montagu.44 In her case, where she was able to penetrate the harem where men could not, her writings serve as invaluable documents to what for the Western man was another world and a most coveted sexual frontier. But these zones of supposition were not confined to heterosexual sensibility alone. In Virginia Woolf’s Orlando, Turkey becomes the liminal zone of sexuality, where the eponymous protagonist transforms from woman to man. Clothing is a central modulator in this change, as it is represented by Woolf as having few differences between genders. But as Matthew Beeber notices, this is a misrepresentation of Ottoman dress, and something to which commentators of the novel have given scant attention. By figuring Turkish dress as largely being androgynous, he argues, Woolf mounts a veiled critique of the traditional Victorian image of the Orient as sexual and feminine.45 While critics have addressed the issue of androgyny, they have not gone further to observe how incompatible its application is to actual Turkish fashion and dress.46 One item in particular, baggy trousers, is used by Woolf to reveal this lack of difference. Yet, as Beeber argues, these are “a trope, a symbol of androgyny and sexual freedom in the East, a symbol especially powerful in the imaginations of Victorian women for whom the trousers might appear mannish in comparison to burdensome crinolines.”47 Woolf’s diaries from Constantinople nonetheless identify the strong demarcations between the sexes, suggesting that the misreading of fashion was motivated at dispelling reigning clichés by Victorians of Ottoman fashions and mores.48 Woolf was well acquainted with the writings of Montagu, whose vision had become influential to British notions of the East. For Montagu stressed the “liberties” of women’s dress and movement, afforded by dint of concealment. The “liberties” that Montagu spoke of were also interpreted into a sexual realm, naturally enough. Yet Woolf was well aware that Montagu contributed to the feminization of the Orient: Montagu’s privileged and selective outlook, portraying a far more relaxed role for women, elided the grimmer truth that it was men who had mobility and it was in their interests to curtail the movements of women.

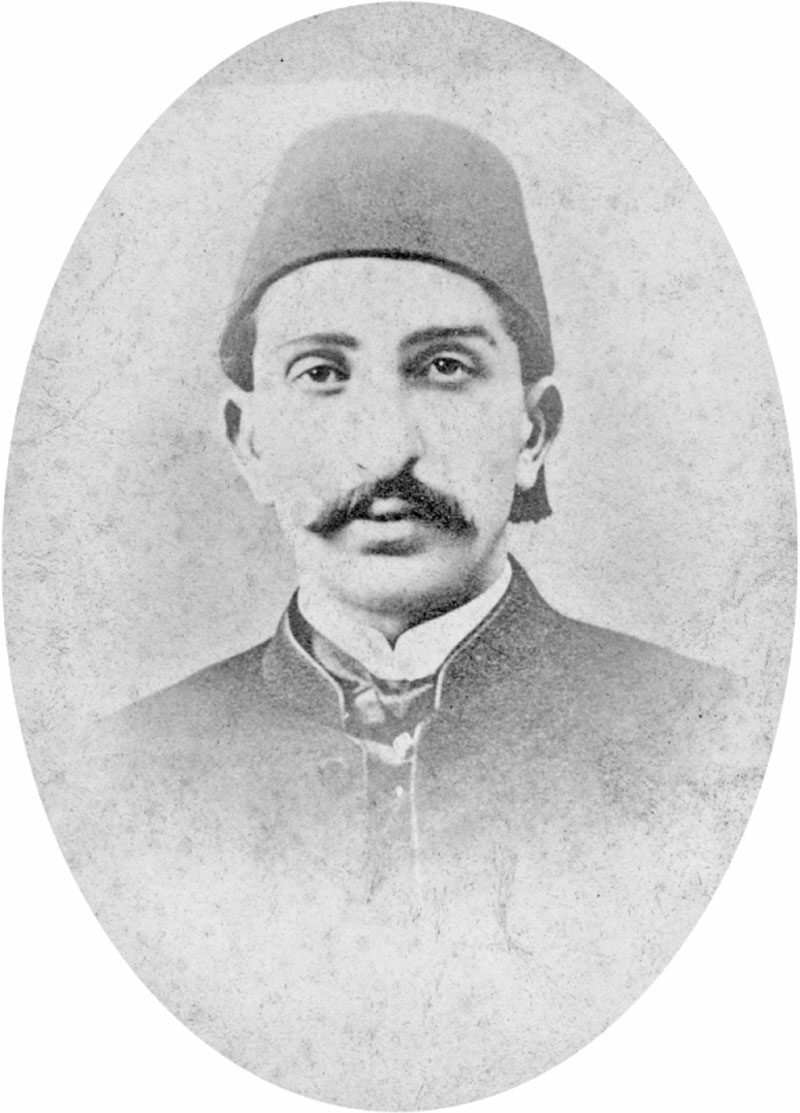

Figure 2 Turkish woman c. 1885. Photo by Adoc Photos/Corbis via Getty images.

True enough, the image of the Ottoman woman, covered from head to toe with only a small slit for the eyes, continues to be a prevailing one, and seductive not only for eliciting endless speculation, but for presenting such an easy generalization for representation and critique. However an important correction needs to be made at this juncture. For the idea that all Ottoman women were veiled in the nineteenth century is as sweeping a generalization as the brash Western equation of the hijab with women’s oppression and Muslim tyranny. Ottoman women well into the early years of the Republic wore veils in different ways and situations, based on their class or their own cultural views. For example, the peasant women in Anatolia were not veiled but wore a headscarf and only concealed their lower face in the company of men with whom they were unfamiliar. Similarly, the Westernization of women’s dress in the nineteenth century occurred at differing degrees depending on women’s social station and whether urban or rural. The latter not only were limited in means, but were also less exposed, and less receptive, to outside trends and changes. Being mindful of the ethnic diversity of the Ottoman empire, different groups adapted at different rates: peoples who identified with Greece or Armenia, for example, accepted Western changes with greater rapidity than their Jewish or Muslim counterparts.49 Reforms continued in fits and starts. Sultan Abdülamid, for example, banned women from wearing several items of clothing (the carsaf, ferace, and the yasmak) as he believed that they did not sufficiently comply with the requisite modesties of Islam.

Curiously, it was also Ottoman women’s fashions that played a cardinal role in the liberation of European women from the corset and the stay. Ever since the eighteenth century the Ottoman empire had been highly conscious of European ways and how they differed or may have improved on their own. It was a preoccupation that accelerated in the mid-nineteenth century, in no small part fueled by the Sultan Mahmud’s example, that Ottoman women began experimenting with Western fashions, which also included the corset. It was also by showing signs of influence from Paris that upper-class women could register their sophistication, and also distance themselves from the antiquated lower classes. Further, the rise of department stores at the end of the nineteenth century, and the greater circulation of goods together with advertising material ensured that Turkish women with the right means had a whetted appetite for European goods. During this period, it became common for upper-class women to wear a long flowing coat, the ferace, to have their faces barely covered, and to have replaced the terlik, or slippers, with boots with high heels. Meanwhile, by the end of the nineteenth century, lobbyists for Women’s rights, the suffragettes, became synonymous with bloomerism. “It is remarkable,” as Inal remarks, “that at the same time as the salvar and entari became a fashion of high society in Britain, it was simultaneously replaced by European dress among the elite women of the Ottoman Empire. The same type of clothing that symbolized authenticity, showing off and wealth in Britain represented the old and traditional Ottoman society.”50 Abandoning the corset and wearing baggy pants was more than an attempt at comfort, it represented an entire new perspective on the way society should be organized. Later in 1911, after his Thousand and Two Nights party, Paul Poiret would credit himself with having freed women from their sartorial encumbrances, when in fact this had been occurring over decades, and in no small part to the exchanges in influence between Ottoman and European women.

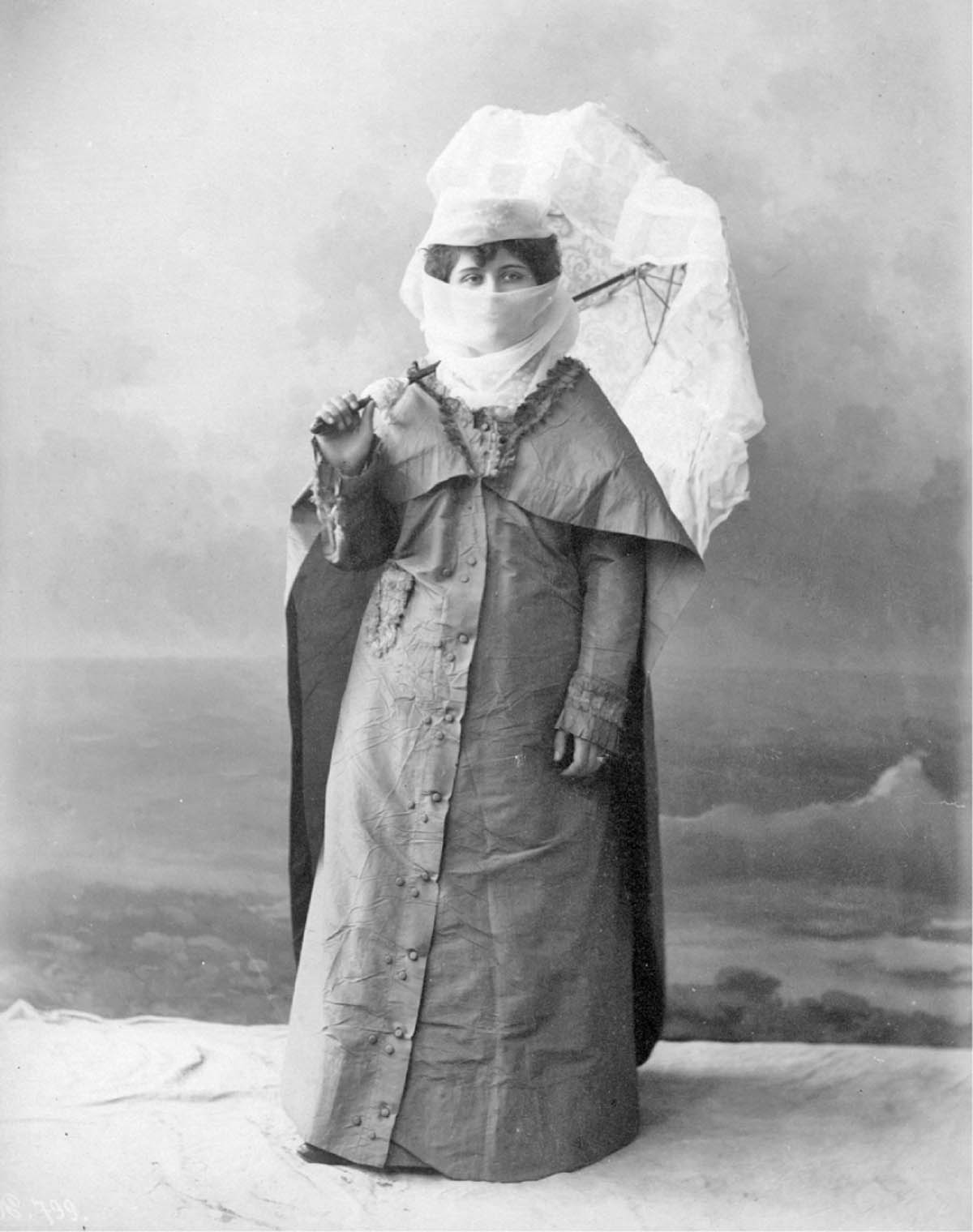

Figure 3 Turkish woman c. 1885. Photo by Adoc Photos/Corbis via Getty Images.

Women were banned from the veil in 1935, ten years after the proscription of the fez. This cannot be seen in isolation, but rather as grouped among a series of Atatürk’s “civilizing” reforms, which included women’s education and literacy as well as political participation. Around the turn of the century the most popular forms of clothing for middle and upper-class women were the çarsaf and the peçe. However, like the fez, by the 1920s these garments became seen as retrograde statements of a stagnation.51 The çarsaf was a single, loose piece of cloth that covered the whole body. But once cut in half, it could resemble something of European taste. The upper garment formed something like a cape, and the lower body a skirt. As the skirt evolved, it became shorter and narrower, while the peçe, the transparent face veil, was replaced by the scarf (esarp). The stories of women’s dress, up until the Republican reforms, are the vicissitudes of conservative perception as to the appropriate signs of modesty and devotion in women.

The debates surrounding the relationship between clothing and religion have already been traced above with regard to the fez, but with women’s clothing the focus was elsewhere, since the codes of guardianship began with a woman’s own body. Women who responded to the reforms were frequently met with violent responses such as being spat at, being stoned, or having knives drawn on them. Yet both the Balkan and First World Wars were significant catalysts that made more women participate in contemporary life where they were more visible and responsible. Earlier in the nineteenth century women worked in positions such as nurses, journalists, and teachers, but the shortage of male labor precipitated by the wars meant that the roles open to them expanded to those such as clerks and factory workers. In Istanbul their placement in menial labor extended outward to street sweeping. Women therefore played a sizeably greater part in public life. In 1915 an imperial decree made it admissible not to wear the veil during working hours. As their agency increased, so did their compulsion to express it, so that discarding the veil seemed perfectly natural, like relieving oneself of an anachronistic impediment. After the war, with social agitation fomented by the shame of defeat, the clamor for abandoning the veil for good gained momentum. More and more female activists declared the necessity of modernizing dress.

The promulgation of the Hat Law for male citizens eventuated in the headscarf replacing the veil as a signifier and safeguard of women’s modesty. And while ardor of belief varied according to class, and whether one lived in a city or the country, tenacious binaries established themselves. The çarsaf and the peçe were viewed as upholding decency, tradition, and the correct position on religious belief; they were deemed by reformists as stultifying anachronisms. In turn, those advancing reform were cast as abetting moral decline and moving in a direction that dishonored Turkey’s past. The rhetoric of tradition is seductive, since it implies that the glories of the past can only be regained through lip service to it. But certainly, despite the divide between men and women in Islam, the differences between the more modern men’s clothing and that of women became more pronounced, suggesting an urgency to make dress more equitable, which is also to say more modern. Nonetheless, as Yilmaz suggests, “among large segments of society, women’s dress, their visibility, education, and employment, and the regulation of male-female relations continued to be perceived through local, tribal and religious lenses.”52 The status of women’s dress remained more fluid than the more policed male counterpart, and in many cases appeals for voluntary abandonment of older forms of dress went unheeded. This escalated in mayors issuing more stringent edicts, but the effects were again uneven. This did not deter the Shah of Iran, Reza Shah Pahlavi, from embarking on an unveiling campaign after his visit to Turkey in 1934. But for him, too, propaganda proved ineffective, prompting him to enact in 1936 laws making it mandatory for women to unveil.

It was also around this time that the Turkish government invited intense debate about the çarsaf and the peçe. By this time, it was observed that women in the provinces, which amounted to about two-thirds of the Turkish population, wore neither. One question centered on why the relatively small fraction of women still refused to jettison the peçe, or headscarf, in particular. Was it an expression of women’s distrust of men? Other arguments stated that clothes that concealed appearance were conducive to crime. A member of parliament, Hakki Tarik Us, was particularly voluble on the matter, waging an attack on conciliatory measures of voluntarism. Changing roles between men and women called for the peçe’s abolition, as it was a powerful medium that impeded such progress.53 Others tended to the belief that Turkish reform was not reducible to clothing, and that more far-reaching perspectives could provide better results. What these various opinions did share, however, was that they were all propounded by men. It was a stark example of the bias that still tainted Atatürk’s otherwise strong push for women’s rights under the new regime. During his brief marriage (from 1923–1925) to Latife Hanim, a woman hailing from a wealthy family and with a European education, Atatürk was accompanied by her on his visits to Anatolia, where she appeared wearing modest European clothing and a headscarf. But Atatürk persistently appeared to officiate women’s dress in the manner of the male counterpart, laying the vicissitudes of women’s dress to those dictated by “fashion.”54 Gradually, by the early 1930s, the hat had begun to supplant scarves, although not without continued pressure on old religious beliefs, especially those held and enforced by men.

At the same time as these complex and fraught cultural upheavals in Turkey, the West was still content to cherish a stereotypical view of the former Ottoman Empire. The 1920s witnessed quite dramatic changes in women’s dress, allowing for greater mobility. It was at this time that masquerade, now in the modernized term, “fancy dress,” experienced a renaissance in popularity not only due to party culture but to the significant rise in various forms of media and entertainment, including cartoons, films, and the widening ambit of print media ranging from guidebooks to fashion glossies, which were already disseminated in ever-greater number before the War.55 One of the more popular examples that could be bought off the rack at Harrod’s department store was called “Turkish Delight.” This was the only version with direct cultural inference: others in the line included “Merry the Bright” and “Queen of Hearts,” as illustrated in the 1927 catalogue Fancy Dress at Harrods.56 “Turkish Delight” consisted of a splayed feather head-decoration, repeated pleated riffles at the waist, loose-fitting striped pantaloons, and shoes with an upward-turned tip. This is but one small instance of a multitude of cultural dissonances that, while ostensibly innocent, are prevalent until today. They are preponderant in the way in which artists are forced to broker their identity against false or misinformed assumptions about their country of origin. In the case of fancy dress in the 1920s, it did not sufficiently serve the Western imagination to look at what Turkey “really was.” This oscillation between inner desire and compulsion and the pressure of external perception is an ongoing theme of this book.

If Atatürk had demurred from securing a law against headscarves in his own time, it was finally put into motion in 1982. The ban was on wearing headscarves for religious purposes in universities and government offices, in other words in all “official” non-commercial institutions related to social service. This shortly led to a number of scandals. On July 31, 1984 the Daily News of Ankara published an image of three female students in academic dress, one wearing a turban. They had been celebrating their graduation in Medicine at the University of Ankara. The turbaned woman happened to be the top student, who traditionally delivered an address to her fellow graduates. In this case, owing to her head covering she was prohibited from doing so. In the previous week there had already been instances of women in universities falling afoul of the law: in Uludag University in Bursa four students were suspended after arriving in head coverings that were said to be “turban-style.”57 And a junior academic of Chemical Engineering of the Aegean University in Izmir proclaimed that she would resign if unable to wear her headscarf, adding, “This is My Philosophy of Life.”58 In an attempt to stave off mounting controversy, the rector replied that Dr. Koru, the academic in question, was at liberty to wear anything on her head when off-duty. The ongoing debate saw other women speak out in defense of the government laws, highlighting how polarized Turkey still was over the issue. By July 29, the Istanbul newspaper, Milliyet, which had been covering the saga, finally reported the University’s announcement of the right to dismiss Dr. Koru.

The question still remains as to why these events raged potently in Turkey until as late as the 1980s. One reason Emelie Olson cites is in the vast ethnic diversity, and hence the variety of values and beliefs in Turkey. Just as the government used clothing to leverage its policies, people dissented in kind. “By 1980” states Olson, “Turkish society had become politicized to an extreme degree.” There were numerous acts of violence and civil unrest:

Confronted by this breakdown in public order, the authorities decided that the manipulation of dress as political symbol contributed to the tense situation. The conspicuous and constant “signing” of religious and political views through dress and hair by extremists on all fronts was seen as both inflaming passions and making the “enemy” on both sides identifiable to snipers and assassins.59

The problems were historically deep seated. As the Turkish economy showed no great signs of prosperity, certain people would look back with nostalgia to what they saw as the prosperous Ottoman past. While not fully embraced by Western Europe, Turkish people were far from unified in their view of modernization, which singled them out as a Muslim nation from other neighbouring states that were once part of its dominion. In short, the dress reforms, as seen in the long term, came to be regarded by some as leading to Turkey’s isolation. It was a complaint that could not be made with due decisiveness, however, as many of Atatürk’s reforms had had positive results. For many modern Turkish people, they felt inserted into an uncertain space, parked indifferently but agonistically between Occident and Orient. At the end of the twentieth century, for many who looked ambivalently back and who also saw an unclear future, Turkey’s rapid alteration was an example of what Bhabha (writing of Indian and African colonialism) sees as the compromise that comes with “mimicry.” Bhabha’s pun, “Almost the same but not white,”60 is painfully pertinent to the Turkish experience, where emulation only amplifies the many aspects in which the many intricate acts of mimicry fall short.

The tensions that arose in the 1970s were also highly influenced by the women’s movements in the West, and other racial protests that had gained momentum since the early 1960s. Turkish women used the headscarf as a way of registering their difference from both men and the West. By then it had a complex status, since its abandonment had been a sign of women’s liberation. Yet it was increasingly seen as a partial liberation, organized by men. As Valorie Vojdik points out, “a certain group of women—young, urban, and typically daughters of migrants from the rural periphery—deliberately embraced the headscarf, challenging the secular elites as a political matter.”61 A salient issue in these challenges was that of what women saw as their inalienable human rights. By the new millennium, meaning and instrumenting of these rights had become convoluted from a global perspective. Turkey forbade the headscarf, yet Iran mandated it. The United States granted the right of choice to Islamic women, while France banned headscarves. In response to the French ban on schoolgirls’ scarves enacted in 2004, in 2005 the Turkish government revisited their own law. They concluded that it was not in violation of human rights, but a restriction that protected the beliefs of all citizens by ensuring that religion was not made overly manifest.62 Vojdik emphasizes that these overarching arguments on the part of the government mask the reality that it is a law that centres on masculine power over women’s bodies. “The headscarf debates” illuminate “the reciprocal relationship between the construction of the state and gender relations.”63 But such considerations should never elide the fact that the veil is a highly fluid sartorial trope. It cannot be considered as an instrument of Muslim male control, but must be seen as a cipher for what are often conflicting practices and beliefs. In surveying the way that contemporary artists deal with veiling, Amer finds that

Muslim veiling clearly never refers to one singular type of practice, nor does it have one universal meaning or unique form of expression. Rather, veiling describes a multiplicity of experiences. It is controversial only because it is a visible marker whose meaning cannot be contained in or grasped with a single or simple explanation. The meaning of the veil can only be revealed through the exploration of its shading, its range of expressions, its contradictory practices.64

We might also make peace with the notion that the campaigns to “liberate” Muslim women from the veil and the scarf are past, state laws as in France notwithstanding. We must resist, it seems, reductive views about veiling and instead embrace it as a multivalent sign of both submission and resistance.

Figure 4 Turkey’s ruling Justice and Development Party (AKP) MPs Nurcan Dalbudak (centre) and Sevde Beyazit Kacar (right) attend a general assembly at the Turkish Parliament wearing headscarves in Ankara on October 31, 2013. Four female lawmakers from Turkey’s Islamic-rooted government attended a parliament session on October 31 wearing headscarves for the first time since a ban was lifted in the staunchly secular country. Photo: AFP PHOTO/ADEM ALTAN/AFP/Getty Images.

It would be feasible to conclude that the headscarf, and related head covering, worn for itself and not, say, as protection from the elements, has emerged as very much a political instrument pertinent to both the self and the state. Instead of protection from the elements, it is a barrier, a partition between male presumptions and women’s private worlds, and symbolic protection from the regular ideological onslaughts from Western reproaches of Islam. It is a multivalent instrument. Where it was once linked to nostalgia and traditionalist intransigence, it is now an inflammatory device for women against imposture, the impositions in both words and actions of power against them.