It has fallen from some people’s memories that still in the 1970s, many countries with a colonial past treated the “art” of its indigenous peoples as cultural products, as artifacts. Granted, art is a fairly circumscribed discourse with its roots in European history. Like the ancient Greeks, indigenous cultures did not have a word for art, since what we now classify as such was a component of ritual devotion or social initiation. Indigenous “art” was lumbered with the unwanted problem of either being treated as anthropological data, or being subject to a set of rules and expectations foreign from its meaning and making. Then, in an abrupt turnaround, with the revisionist attitudes that percolated into the last decades of the twentieth century, these artifacts were treated with veneration, bordering on awe. They were the reminders of the culpability and guilt over colonization. Where they had once been scrutinized, analyzed, and placed into taxonomic order, they were the object of a respectful gaze, so respectful that no word or judgment was passed for fear of overstepping one’s cultural mark, and of assuming again the role of the presumptuous white man pursuing his colonizing “burden.”

Such generalizations are useful, although the details always vary. In the interests of coherence, this discussion will be confined to Australian Aboriginal culture, with the main focus on the visual arts. For, given the political delicacy of the debates over indigenous rights, any analysis can soon spill out. It is also that Indigenous Australians have an unusual, if not unique, claim themselves, with evidence of existence for some 60,000 years. Further, they are far from homogeneous, being as diverse in language and custom upon British settlement in 1788 as Europe itself. And since the 1980s, Aboriginal art has been an object of international fascination. From this time, art was also the singular most significant agent in bringing visibility and traction of Aboriginal peoples to the non-Indigenous population.1 Now firmly entrenched within national and international art markets, the efficacy of this art for advocacy of rights and identity is now subject to review. One reason is that where once Indigenous peoples (note the plural) were homogenized like all groups of subaltern status, the sheer growth, depth, and pervasiveness of Aboriginal cultural activities since this time militate against such a view. The effect is to reveal a breadth of experiences, attitudes, and histories that encompass vastly different, and often contradictory, positions.

Not only does the enormous diversity of Indigenous Australian cultures make them a pertinent study for this book, it is also the diversity of the ways in which they have inhabited, appropriated, repositioned the colonial languages—written, verbal, musical, visual—for themselves. Beyond the objects themselves there is the very delicate matter of the Aboriginal self. To begin with, the diversity of Aboriginal peoples was not only of language and custom, it was also in appearance. Not all were “black” in the sense of appearance. The blackness that the settlers reported of the Gadigal people of what is now the Sydney region was not so much their skin, which was comparatively lighter than other groups’ from the desert center, it was due to the ash they smeared on their body as protection from the sun (the first settlers arrived in the height of summer).2 In comparison with other dark-skinned people, Africans and African Americans being the obvious example, the melanin gene for Australian Aboriginals is a recessive. One of the shameful chapters of Australian history was the government policies’ attempt to “breed out” the blackness, which could be achieved in only two or three generations. This means that “blackness” for Indigenous Australians is varied according to more than one criterion, and that “blackness” is not limited to appearance—hence the recent coinage of the term “blak” to designate a trait that is expressed through tensile mixture of pride and resentment. Aboriginal identity thereby proves to be a vexingly elusive notion, which makes it so apposite a subject with which to conclude this book. It is a platitude to say that external appearance is a central element of inner identity. But what is it when the conventions governing appearance, held by more than the dominant group, are discordant with inner identity? What is it, for instance, not to know of Aboriginal heritage, only to discover and identify with it later in life? In that case, to what extent can one claim blackness if one had hitherto no experience of it in the material and socio-symbolic sense, that is, as having been treated as “black”? What are the signifiers of identity in such an event? These are very real, and, to wit, insoluble questions from a long-term perspective. For versions of them are pitted daily amongst Indigenous Australians themselves, and one or another is faced with the imprecation of being “not a proper black.” This has caused many eminent Aboriginal commentators to turn to the concept of inter-culture, trans-indigeneity—and sundry other cognate neologisms—in order to find a site of identity that is not dogged by an identity politics of insufficiency, which can only be a politics of self-impoverishment.3 It is yet another manifestation of the transorientalist “third space” or “between zone” in which the genuineness of belonging is untrammeled by essentialisms such as purity, since “Australia” is from the very first the name of the adulteration and cataclysm of Aboriginal culture, but where there is also the rejuvenated space of renewal and an active future.

Attempting to assess the status of indigenous art in the last thirty or so decades can never elide the history of its uneven reception by the West since the growth of colonialism and imperialism from the sixteenth century onward. Naval trade and colonial claim occurred together with the birth of modern science and with it the museum. The first museums were collections of “curiosities,” or Winderkammern.4 These began as miscellaneous collections of curios consisting of natural and man-made objects, that, when they grew, required ordering, hence the earliest conjunction of curatorial and scientific taxonomy. Objects belonging to “primitive” peoples were part of this mix. It was only in the eighteenth century, with the thought of Herder and Rousseau, that these objects were given a slightly higher value as belonging to a class of people who in some or many ways may be superior to Europeans. The “noble savage” was one class of early modern genre that was unconfined to any land in particular, being another subgenre of Western self-definition. Similar to the roughly contemporaneous conception of the “Madonna-whore” binary, the noble savage-simian was defined by, and situated outside, the realm of the white man. If not treated as subhuman (simian) or as superior humans, both were abstracted out of reach of knowledge or attainability. Hence the famous engraving by William Blake of an Australian Aboriginal family. There is very little to separate them from other indigenous, such as Polynesian, peoples, and apart from a few irregularities such as the child on the mother’s back and the weaponry, they resemble Greco-Roman figures only with darker skin.

The noble savage continued to exert a powerful influence over artists, writers, scientists, and philosophers throughout the nineteenth century. Indigenous people, or their interpreted stylization, were regularly inserted into landscapes by Australian colonial artists. The new landforms and foliage were given iconographic security through an idealized pictorial order that paid academic deference to Claude Lorrain, and other progenitors of European Landscape painting such as Salvator Rosa and Nicolas Poussin. In such works, the Aboriginal was placed gingerly leaning on his spear on one side of the foreground, usually contemplating the white men’s business of sea-faring or town-building. But the quaint representation of the Aborigines did little to temper the long-held view of the English that they were inferior and objectionable. One of the earliest explorers to touch the shores of Australia, William Dampier, judged the Indigenous people he encountered to be “the miserablest People in the world.”5 The colonists would not err from this view, ranking them as “scarcely human” and “the most hideous of all living caricatures of humanity.”6 This did not deter artists from images of an Aboriginal arcadia, an unknown place before European contact, which would prove to be popular with naturalists and anthropologists back in Britain.7 Because these untouched natives were of an inexperienced and non-empirical past, their romanticized repertoire was fairly limited and repetitive, and ultimately expressions of the contradictions within the white man’s longing for the Other: the Other was admissible and desirable when inaccessible and a figment of Western desire.

When the already well-established English painter John Glover came to remote Tasmania to retire, he thought he had found an earthly paradise. He arrived in 1831 when whites and blacks were pitted in deadly war. Within a few years the indigenous peoples were all but wiped out, but that did not stop Glover from painting landscapes with Aboriginal ceremonies and activities that showed them to be in a state of ecstatic harmony with nature. In many ways, these efforts to offer an untouched, unharmed representation of Aboriginals were self-serving, and they had the effect of keeping the unwelcome facts from view. Other artists, such as Augustus Earle, made images of the downtrodden Aborigines in towns, inebriated and degraded. But they do not elicit empathy, they only confirm the prejudices of aversion and abjection that Aborigines still, to this day, continue to suffer.

A brief gloss of the history of representation—one that hardly touches on the extent and ugliness of this past—is enough to give some background to the reception of Aboriginal art at the end of the twentieth century until the present. Australian art in the first half of the twentieth century was not so much in thrall with “primitive” art in the way that the European avant-garde was, where it was used as a late-Rousseauean antidote to civilization and as a gateway to spiritual authenticity. One artist, Margaret Preston, used Aboriginal styles and motifs, what might today be called “Aboriginalizing” (in the way that Pre-Raphaelitism was “medievalizing” and, as we saw earlier, how chinoiserie is “chineseifying”) in her later works of the 1940s and 1950s. These are quintessential primitivist-modernist works in that they are all surface and style without any interest or understanding of what these styles related, sometimes even submitting the Indigenous look to Christian iconography. Preston was at a certain point later lauded as someone who was a defender of Aboriginal art, a more than disingenuous claim, as she was uninterested in the sacred narratives behind it, let alone the cause of the Aboriginal peoples themselves.8 With this eccentric exception, apart from working from European stylistic cues, Australian modernist art is notably bereft of primitivist influence. At around the same time that Preston was plundering randomly from Aboriginal art (and originating from areas she had never visited), one Aboriginal artist was active. Albert Namatjira is hailed as one of the pioneers of Aboriginal art, his success at the time a result of having mastered Western representative techniques of landscape painting. (It would later be uncovered that these were all Aboriginal sacred sites, in keeping with the secret-sacred nature of traditional Aboriginal art.)

Art history tends to like a fixed origin, or the illusion of one to be used as an historical touchstone. The stylistic watershed such as the miraculous and unaccountable invention of Cubism (1907–1914) is one of the modernist myths of vision and capability deemed lost in the chaotic plethora of postmodernism. In the 1970s, art had already branched out into tendencies and practices, many of them of multiple origin and with more than one name (Body Art, Performance Art, Live Art, Happenings, Lettrism, Word Art, Art&Language, Land Art, Process Art, Fluxus), which largely come under the aegis of Conceptualism, art in which the idea has as much or more precedence than its material product. Now seen in retrospect, the birth of Aboriginal Art in 1971 is contemplated with the warm glow of something certain, the beginning of the art of something authentic in a period of artistic indeterminacy and dematerialization. It is also universally considered the point at which Aboriginal visual practices made the turn to enter into the sphere of Western art discourse. There are earlier isolated instances of Indigenous artists encouraged into Western methods—such as in 1946–1947 when the anthropologists Ronald and Catherine Berndt gave the locals in Milingimbi and Yirrkala paper and crayons to illustrate their stories9—but the genesis in Papanya was the richest and is referred to the most.

In 1971 Geoffrey Bardon, an art teacher from Sydney, was posted to the remote government settlement in Papanya to the northwest of Alice Springs. Also primly called “missions” to give them an air of purpose and propriety, settlements like Papanya were effectively the equivalent of detention centers for local indigenous people who had been relocated from their ancestral lands and forced to live in semi-captivity. Bardon found over a thousand people living in a state of dejection and unrest. In his words: “I found a community of people in appalling distress, oppressed by a sense of exile from their homelands and committed to remain where they were by direction of the Commonwealth Government. Papanya was filled with twilight people, whether they were black or white, and it was a place of emotional loss and waste, with an air of casual cruelty.”10 The origin story of Aboriginal art is often described with notes of redemption, when its real circumstances were fraught and traumatic. Bardon observed that elders were relating stories to one another, which they recounted while simultaneously drawing patterns in the sand. He provided them with what painting materials were available, and scavenged materials, such as a sawn-up old table, were used to paint on. Their work was also articulated with crayon or pencil on paper. Overall, the imagery depicted their relatedness to the places from which they had been taken; these are called the “Dreamings” in which the material of nature cannot be extricated from the spiritual within them. Although very little of the earliest works survive except in documentary form, Bardon’s insight and initiative led to a movement that has since joined Aboriginal art royalty, including Johnny Warrangkula Tjupurrula, Long jack Phillipus Tjakamarra, Old Mick Tjakamarra, Johnny Lynch Tjapangati, and Clifford Possum Tjapaltjarri. The paintings that have survived them are now treasured and held in Australia’s national and state collections. They are also in eminent corporate collections, many ironically the beneficiaries of the policies that led to the dislocation of these and other peoples in the first place. Indeed just as the Japanese fire-insurance company Yasuda bought one of van Gogh’s Irises for $39.9 million as a gesture to refute Western suspicions over Japanese corporate stolidness and inhumanity, it is now a common practice for large corporations such as those involved in mining, fracking, and land development, to “sanitize” their activities by investing in Aboriginal art and showing it in their corridors and boardrooms.

Despite Bardon attesting that when the artists felt comfortable and well-treated they were forthcoming about the meanings of what they were painting,11 there is another layer to Aboriginal art that remains sacred and secret. Strictly speaking, all “traditional” Aboriginal art (in scare quotes as this term has been rewritten several times over the decades) is sacred. There is no separation of activities or genres as there is in Western art. Causing more complications is the matter of the secret, which means that certain meanings are only available to the initiated—it is also possible for an artist to be permitted to use a certain motif without having yet been initiated into its fullest meaning. All of this is anathema to modern Western art, which is accustomed to the separation of church and state, and where it is a given that it is the product of an independent subject. (While attribution to individual works of Aboriginal art is to a single author, traditional Aboriginal artists consider them as belonging to a spiritual and social collective, and it is a regular practice to paint collaboratively.)

Once Aboriginal art had become a cultural quantity on the public market of sales and exhibitions, the tenet of secret-sacred would find itself mired in a number of impasses, beginning with the simple fact of the secularity of the contemporary art market. Many Aboriginal elders were dismayed at the misplacement, popularizing, and ultimately the cheapening of codes and lore that defined the essence of their people for thousands of years. In Christian terms, this amounted to mass desecration. But it was also this awareness by non-Indigenous people that important content is withheld from view that whetted their appetite, and in more than one way. First, it satisfied the primitivist prejudice of something mysterious and proscribed from the white man’s eyes—in Orientalist-speak the metonym for this is the harem. And second, when something is not given, it is for that all the more desirable. Third, the visual syntax of the unknown was a hieroglyph to be deciphered at moral cost; such was the will of the colonialist, not to respect the secrets of the colonized. So for some content to be unknown, and for the non-Indigenous viewer to know this and not to pursue the meaning, was to satisfy the guilt of colonization. Not to overstep the barrier of difference was to show benevolent obedience to revisionist ideology. Finally, the frontier of the unknown and the unknowable proved exceedingly convenient to the Australian and international curatorium, for it meant that there was nothing they needed to find out about. Inaction and a lack of curiosity were rewarded with the belief that you were doing your postcolonial, post-Orientalist duty.

The debates that were waged about the new forms of display within Aboriginal communities themselves were without consensus, revealing the many differences in custom and tradition. Identified early was to resist the restrictive typology enforced by Western “primitivist” anthropology that ritually integrated societies were cyclical, while Western society was progressive. A slow but growing consensus was that for Aboriginal art to be taken seriously as on par with the best non-Indigenous work, it must be open to the same channels of criticism and assessment. This still posed problems for the critics, which included Indigenous ones, uninitiated into the traditions of an artist of a particular country (the name now given the region of a particular group). The big question, the proverbial elephant in the room, was: how does one gauge spirituality? Is one painting more adequately spiritual than another? But the role of critical legitimacy also fed into artistic legitimacy. For the dots that are the most famous feature of Aboriginal art are not germane to all Indigenous peoples. Yet even as early as the 1980s, with the popularization of Aboriginal art, they had begun to be used by artists for whom it was not their indigenous style. Non-Indigenous artists also made forays into dotting, some with the excuse that they had been granted use of the dot by an Aboriginal group. But which group is able to do so? There are also recent cases of young white artists brazenly copying traditional Aboriginal styles, which caused outcry by Indigenous and non-Indigenous alike. Ultimately, the question of appropriating sacred Aboriginal styles and motifs—the question of “who owns a dot?”—boils down to one of disenfranchisement. It is one thing to appropriate Western art, but it is quite another to take indiscriminately from peoples who, at the time of writing this, are still not written into the national constitution.12

By virtue of sheer quantity, however, dots are very much the “trans-style” of Aboriginal Australians. Their universality has occurred together with that of the musical instrument, the didgeridoo, the onomatopoeic pidgin, whose real name is the yidaki, a sacred instrument of the men indigenous to the northwest cape of Arnhem Land. The dot designs were based on the Papanya “classics” of the Bardon years, but like all overcirculated and hypersimulated imagery, the dot has become unmoored from its origins and assumed its own status as a universal. It is on ties, on tea towels, linen coverlets, T-shirts (most of which are made in China). Dot designs now behave as floating signifiers of Aboriginal presence and identity, with an iconicity rivaling the design of the Aboriginal Flag (the design of an Aboriginal artist, Harold Thomas). Like all such universals, they slip into becoming solipsistic and static. And like all universals, they are used by people whose cultural positions and identities usually amount to the opposite, namely they are used to give continuity to discontinuity, to give regularity to irregularity, certainty to uncertainty. But in other circles of Aboriginal Australia the dot and the didgeridoo are eschewed, and it is this complex hybridization of identity and identity manufacture that can be the most intriguing and engaging.

Although the didgeridoo continues to be an item of fascination for Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians, contemporary popular Indigenous music expresses the plight of its people in forms that blend recent mainstream styles. While many practitioners leaning in preference to country and western and reggae, Indigenous music reveals yet again that the expectations about what such music should be are still those of a largely white outsider’s perspective. For while aspects of Aboriginal identity continue to circulate around an instrument like the didgeridoo,13 the most creative and heartfelt Aboriginal music is a bricolage of elements which are hard to categorize as a whole. As an analogy to much contemporary Aboriginal art, Aboriginal country music reveals how fraught are the notions of what may be deemed correct or authentic. And it is yet more evidence that standards of authenticity belong to the venerable ideology of the Western obsession with primitive man as the bearer of a stable truth.

In her close study of the popular Indigenous music of Central Australia, the Swedish anthropologist, Ase Ottosson, proposes that:

Every performance is a healthy reminder of the futility in trying to fix categorically what others and selves are and can be. They provide a counter-narrative to a globally widespread preoccupation with defining and purifying national, racial, gendered and other forms of being in ways that delimit, and, at times, violate, people’s rights to define their experience and existence in their own terms.14

“Mongrel” is used frequently by the musicians themselves for the music they make: a composition of untraceable components and of uneven proportions. It is not a pejorative, as Aboriginal vernacular is much inclined toward giving negatives and expletives positive meanings. Ottosson affirms that “the desert men do not deliver on the privileged and narrow expectations of ‘real’ and ‘authentic’ Aboriginal music and people.” Rather, there is an “ongoing history of appropriations, adjustments, mutual influences, conflicts and mutual ‘othering’ among the parties involved.” The final point is worth pondering, as what is important is the act of resistance through differentiation, and this is achieved through exchange of artistic (musical) expression. Thus identity is wrought through conscious enactment through personal choice and communication. For Ottosson these men “are co-implicated and co-productive in their crafting of changing their ‘mongrel’ selves as men and Aboriginal.”15

Ottosson reports of repeated cases of reactions of non-Indigenous Australians to such music, which is to be perturbed by how it does not comply with expectations and how it does not follow anything that can gauge its authenticity.16 Instead, this authenticity lies elsewhere, in the border-zone of the “intercultural.”17 This occurs not only on the level of style and approach but in social interactions. Music becomes a modulator, or a glue, “for connecting and mediating such different ways of being and becoming men and Aboriginal.”18 To the chagrin of the outside observer looking for hints of the afterglow of the noble savage, the musicians of Central Australia actually avoid mixing ancestral content into their music, or making direct references to them.19 As Ottosson explains, the separation of sacred and secular, of ancestral and non-ancestral, is a given and not the subject of further comment. “If prompted, most of them simply state that ‘the Law is too strong, too secret’.”20 “Law” is purposely ambiguous and purposely definite. But that does not mean that the music that they perform is a diversion or straying from traditions. Now that their brand of country music has been played for several generations, it is seen as having its own ancestry, and its own autonomy, with references to white origins long out of the equation.21 Indeed it is with a miscegenated music that Aboriginal men might share experiences that are global and universal, such as male loneliness, longing for country, falling into crime, or suffering from a broken heart.22 Like many other Indigenous peoples around the world, including the Native Americans and the Inuits of Greenland and Alaska, it is a separation wherein the ancestral forms remain private and are reserved for their relation and claim to land.23 The more overarching insight of Ottosson’s work is to expose the friction between the hybrid, “mongrel” frameworks alive in Aboriginal cultures as against the still regnant academic impulse to prize out “authentic” and “traditional” features for study over other practices that are integral to the changing and heterogeneous nature of Indigenous groups. “It is through attending to these and other forms of overtly (inter) culturally messy practice that we can begin to account for the multifaceted and place-specific ways in which indigenous people experience, act and identify in their contemporary lives.”24

The digression into the contemporary Aboriginal music of Central Australia acts as an alibi and counterpoint to the yet more “messy” philosophical and political configurations of contemporary Aboriginal art. The artists that are singled out here—Richard Bell, Blak Douglas, Tracey Moffatt, and Christian Thompson—all present provocative alternatives that explode the tenacious beliefs in a homogenized and authentic core to Aboriginal culture and identity. As artists they position themselves against such preconception and stereotype, and they are formidably conscious of the desire of the white public to categorize and quarantine them. Some more activist than others, their work regularly reflects on Aboriginal art not just as a separate entity, but the opposite as a conjunction. Aboriginal art is no longer to be seen as a style per se but a device, a mechanism, and an idea. Facing bigotry and ignorance is inevitable for any Indigenous person, but the art, which may refute and expose injustice, is also a tool for communication. And in its physical presence in the art gallery or elsewhere, it is a continual, persistent assertion of staking a claim to land and of being present. In his comparison of the differences between Aboriginal and European mapping methods, Terry Smith remarks that: “For those artists who live away from their communities, or who are the children of those separated from their families during the assimilationist period of the 1940s and 1950s, actual or psychic journeying is a frequent subject.”25 This psychic journey may be to a place that has been effaced and the language lost, but is cherished all the more for that loss. The psychic sojourn to the void is an important movement toward reclamation.

Bell, Douglas, Thompson, and Moffatt are artists who are representative of yet another form of identity agonism. Their own artist personas have been exercises of self-recreation, while an artist such as Tracey Moffatt prefers not to be called an Aboriginal artist, despite some of her most celebrated work being penetrating and moving investigations into some of the many dark and deleted chapters of Aboriginal history after white occupation. (She is far from alone is such reticence, which is chary of the way in which artists of color are “primitivized,” and thereby reduced to the tired clichés of “country of origin” and homogeneity.)26 While all have had their share of international success, however, it is “traditional” Aboriginal art that stays the chief interest of the world art market. The division between modern, contemporary—the corollary in fashion is that between modern and ethnic dress—and traditional has become harder to draw, not that Aboriginal art has become more mainstream and institutionalized. Urban contemporary artists, working within idioms proper to artists around the world, from painting to video and installation, believe the constrictions lie in the assumption that it places an embargo on their own claim to spiritual content, while “traditional” artists defend their art to be as contemporary and evolving as any other.

What is certain is that the Aboriginal artists working in the international styles of contemporary art—and this holds for almost all indigenous art that employs similar methods—occupies a transorientalist “third” or middle space. In the 1980s, when urban contemporary Aboriginal artists began to be identified as such, the common ethos was that of an anomie to the visual languages they were using, as they were not of their choosing. (The paradigm in literature is Irish writers writing in English.) However this has changed for many artists who simply see the numerous styles and conventions of contemporary art as a global lingua franca—much as Indian literature embraces English. To advance this notion, one need only look at Blak Douglas, the trade sobriquet for Adam Hill. Born of a dark-skinned Aboriginal father and a white mother of Irish extraction, “Blak Douglas” signals this duality in a synthesis in which this duality is maintained. In name, it enunciates Spivak’s “double bind” but displaces the need for a solution, the solution lies in the symbiosis not the sublation.

In 2003 Richard Bell won the Telstra National Aboriginal and Torres Straight Islander Award, considered the most prestigious of its kind, with the painting, Scientia E Metaphysica (Bell’s Theorem). It is an iridescent irregular patchwork grid dominating a black ground on the left and a white ground to the right, with the words in various fonts, “Aboriginal Art is a White Thing.” Overlaying the primary surface is a large red triangle and snaking dribbles of white and black paint. (By this time the references to Pollock had become fairly established, as it drew a parallel between the desert artists who painted on the horizontal with Pollock’s drip technique.) These words would soon become a mantra for Aboriginal artists. The use (imposition) of Western techniques, media, and ideas had long been politely questioned, but Bell’s work, and others related to it, had a catalytic effect. For one, they placed the ethics of making, exhibiting, and selling Aboriginal art at the epicenter of contemporary Aboriginal culture, exposing the many acts of bad faith by white people. This included the well-known exploitation of Aboriginal artists with limited English, reluctance to enter cities, and no knowledge of the art market. By the new millennium, Aboriginal art had reached the establishment, and it was a convenient means of assuaging the conscience, a mechanism of cleansing the past, in which Aboriginal art performed an erasure, literally a protective aesthetic screen over the traumatic core.

A year before, in 2002, Bell wrote his polemic “Bell’s Theorem,” with the ironic reference to the original Bell’s theorem propounded by the Irish physicist John Stewart Bell (questioning the consistency of predictions in quantum mechanics), whose alternative title, in a convenient twist for the artist, is “Bell’s Inequality.” Richard Bell immoderately argued that the spiritualism in Aboriginal art—which is after all an impassable frontier for the uninitiated—is a form of aesthetic quarantine that is in the guise of respect. Bell demands that Aboriginal art “be seen for what it is—as among the world’s best examples of Abstract Expressionism. Ditch the pretense of spirituality that consigns the art to ethnography and its attendant ‘glass ceiling.’ Ditch the cultural cringe and insert the art at the level of the best in Western art.”27 In the introduction, Bell announces that “There is no Aboriginal art industry. There is, however, an industry that caters for Aboriginal art.” These words have a ringing sound. Aboriginal art is, by implication, both packaged and consumed by forces that are, in truth, hostile or indifferent to Aboriginality as such. Bell counters that Aboriginal art be placed on a par with one of the heroic narratives of twentieth-century modernism, only to suggest that Indigenous Australians had it in the bag thousands of years before Clement Greenberg’s climactic and heroic vision was ever conceived. There are of course more than a handful of problems with this assertion: that it dehistoricizes an historical moment; that it plays loose with spiritual content that many Aboriginal artists hold dear; that it defies cultural specificity—yet these same problems are precisely those that are perpetrated against Aboriginal art. Bell has just turned them on their head. To go back to the art of the white men and say that it has been done better is to perpetrate the same solecisms disregarding context and intention that have ensured that Aboriginal art remains to a large extent insulated from criticism (especially when “traditional”) and ensured its status as floating aesthetic signifiers.

Rousing as it is, Bell’s exhortation that Indigenous artists divest themselves of spiritualism is anathema to other Aboriginal artists who have a sincere and deep bodily connection to people, land, and lore. It does however help to locate another blind spot in how Aboriginal art is consumed as a commodity and an intelligible object. The spiritualism debate with Aboriginal art, or indeed with any culture whose religious beliefs do not conform to the Judeo-Christian model, is subject to adulation or vilification. The spiritualism in Aboriginal art is a convenient no-go zone that insulates Aboriginal artists from commentary, and non-Aboriginal voices from commenting about it. The greatest beneficiaries, however, of this semantic limbo are artists who manipulate the muteness of the spirituality card and the curators who have no stake in formulating any other message than the semblance of “balanced representation.” Nor can the spiritual dimension that ties people, language, and land together, of the majority of genuine (which include ostensible non-“traditional”) Aboriginal art be ignored or transvaluated. Broadly speaking, Aboriginal art, and especially the “traditional” kind, inhabits two realms: that of pure earth and pure spirituality; prethought matter and omniscience. One is particular, the other is universal; both are unknowable and inarticulable. Non-Aboriginal art exists between these two poles, aspiring to both. And yet it is the non-Aboriginal settings of art as we know it—the art market and the loaded ideology of the museum—that foisted these expectations on Aboriginal art in the first place. Since non-Indigenous people “made” Aboriginal art in the sense of enframing it and controlling the way it is distributed and seen, it is preposterous to then expect this art to be more forthcoming about its content. To ask why Aboriginal art is more insulated from criticism than non-Aboriginal art avoids the deeper truth that the non-Aboriginal “system” has made it this way. Airy realms of the inarticulable accommodate a convenient platform for non-Aboriginal art to shape its own fantasies of identity and awareness.28 It is also fair to assert that this is a global problem that spreads to all art identified as First Nations and belonging to a religious ritual system unlike that of the mainstream models.

The quandaries, for both Indigenous and non-Indigenous people alike, of the legitimacies inherent in Indigenous art will remain persistent so long as the subaltern of the “aboriginal” (in the sense of the first person) is maintained, either through neglect or fetishization. But such politics will not allow other perceptions and procedures to circulate. As Ian McLean observes of Bell’s provocation, it “seems more postmodern irony than serious critique, not because it may not be true but because the postmodern condition is as ubiquitous in remote Aboriginal communities as it is elsewhere.”29 By this McLean means the ways that artists exchange motifs, borrow (and steal, following the meaning in the euphemism “appropriation”) from one another, and therefore engage in intertextual experiments. It is also the way that artists play with appearances with strategies reflecting a non-linear perspective of history.

Such ranging across different continuities of time that McLean compares to standards of postmodernism is not a science fiction conceit but is highly credible when considering the much-omitted historical fact of the vast diversity of Aboriginal peoples at the time of colonization. Unlike the residual myths of the noble savage lording over a pristinely contained culture, Aboriginal cultures both past and present have actively sought out exchanges with other groups that help enrich their own. With the introduction (imposition) of other cultures, occupying multiple cultural spaces is the norm for almost all Aboriginal peoples, and for many a cause of pride. The “trans” space not only straddles the white–black nexus or divide, it is global: prominent artists such as Vernon Ah-Kee and Jason Wing identify with both Indigenous and Asian ancestry, Korean and Chinese respectively.

For such artists, including Blak Douglas, mentioned earlier, their work regularly turns to the space of the multiple—it is not the language of the exile or the displaced, but one of ardent dissent predicated by their assertion of a form of belonging not readily given them. For Blak Douglas confronts these issues directly, with exhibition titles such as NotaProppaBlak, signifying the gatekeeping that occurs among Indigenous communities themselves based on the precepts of authenticity used as hierarchical standards. In other works Blak Douglas has made doctored flags with text, which are displayed as floor mats, as commentaries on the barriers and rites of passage between, and within, different racial identities. Moreover, an important arm of Blak Douglas’ practice is collaborative (including with the present author). Since he is seen as an Aboriginal artist (despite the cognate that his assumed name denotes), he sees his collaborations with non-Indigenous artists as more than a complement of minds, but also a political act of common activity, but more than that, as a creative performance that defies categorizing. To what extent can a collaboration between white and black be called “Aboriginal art”? Where is “Aboriginality” situated? What is appropriate to Aboriginal art and what is not? These are questions that need to be asked regularly and will always be met with different answers. Douglas’ work, as in the cultural portmanteau of his name, is a deliberate ideological adulteration that is a fillip to the glib curatorial taxonomies rife in contemporary art.

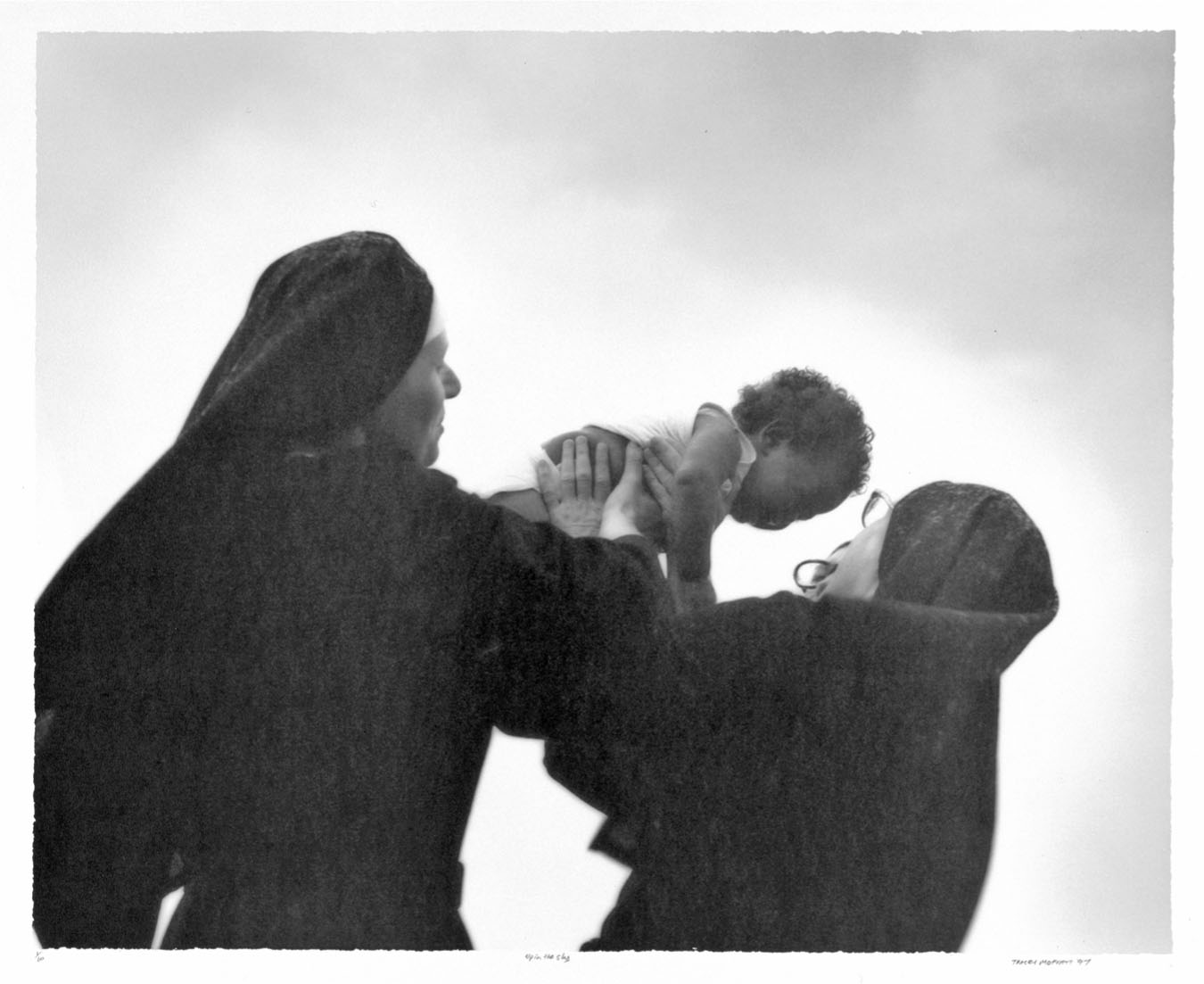

Similarly, the work of the photographer and filmmaker Tracey Moffatt traverses multiple domains, including a longstanding collaboration with the non-Indigenous filmmaker Gary Hillberg. One of Moffatt’s most celebrated earlier works is the photographic series, Up in the Sky (1997), which reads as film stills taken from a larger narrative about events involving the stolen generation, where children were forcibly removed from their parents and “civilized” by Christian missionaries and white parents. In their visual poetry and their haunting empathy, these works had a lasting presence in Australian contemporary art, and have moreover acted as a resonant conscience for the injustices on Aboriginal people. In contrast, her work with Hillberg is predominately of film montages or mash-ups, the best known of which is Love. Consisting of excerpts from the golden age of Hollywood cinema, the work is in two parts, first of violent acts (shouting, slapping) of men to women, then of women to men (shooting). More recent series, such as her contribution to the Sydney pavilion of the 57th Venice Biennale (2017) saw a return to earlier themes. However the suite My Horizon carefully resisted being locked or reduced to Indigenous themes as such. While proclaiming “Indigenous rights,” her installation also proclaimed “refugee rights.” The works spoke to the very present problem of refugeeism and that indigenous rights continue to be bypassed. Searching and contemplative, the photographs and videos revolved around themes of yearning for place and home, all the more powerful for being free of sentimentality.

Figure 38 Blak Douglas, (Un)Welcome Mats, 2010, industrial floor mats, 90 × 180 cm. Courtesy the artist.

Figure 39 Tracey Moffatt, Up in The Sky #9, 1997. Off-set print, 61 × 76 cm. (71 × 102 cm. paper size). Courtesy the artist and Roslyn Oxley9 Sydney.

Also photographic, the work of Christian Thompson engages with the decentered self both as an Indigenous artist of mixed heritage and as a gay male. The armature of his work is almost exclusively his own body, which he drags or dehumanizes. In some works he is a strange and sinister carnivalesque character, in others he is all but effaced by elaborate improvised masks made by leaves or flowers, in some sequences natives. One much-reproduced work is exclusively in the colors of the Aboriginal flag—red, yellow, and black—where the artist is against a red ground, his body painted yellow staring forebodingly at the viewer with blackened eyes, his head covered in feathers, two shooting out on either side. In keeping with what in Western parlance we would call the Dionysian ritual, pleasure and danger come together: this figure is both “primitive” totem and demonic clown. Queering occurs in Thompson’s work in the more subtle sense of drag as an enactment into a transitional state in which the biological self is all but obliterated for the sake of becoming an impossible ideal, an ideal whose traits are often so extreme as to become grotesque.

Figure 40 Tracey Moffatt, Tug, 2017 from the series Passage. Digital C-print on gloss paper, 102 × 153 cm. Courtesy the artist and Roslyn Oxley9 Sydney.

These artists are potent examples of cultural practices—not only in the visual arts but in theater, film, literature, and music—of First Nations peoples in the era of globalization. There is still the need to reclaim place and nation and to safeguard community, language, and lore, but a salient trait is the lack of essentialism in the best of these artists. Many, such as those discussed briefly above, do not see themselves as occupying margins, although they do deal energetically with marginalization, which is not necessarily confined to their own immediate people or group. “Miscegenation” is an unfortunate term for the negative connotation of the prefix, “mis,” which implies an incompleteness or an error. Better to use the term “cognation” to define a state of multiple belonging, and plural commensurability. We all share the same sky, and it can be read in more than one way, and, comfortably, in several ways by the one person.