Put vegetables in the basket.

Put people in the muang.

—Thai proverb

I magine, for a moment, that you are a Southeast Asian counterpart of Jean-Baptiste Colbert, chief minister to Louis XIV. You, like Colbert, are charged with designing the prosperity of the kingdom. The setting, like that of the seventeenth century, is premodern: overland travel is by foot, cart, and draft animals, while water transportation is by sail. Let us finally imagine that, unlike Colbert, you begin with a blank slate. You are free to conjure up an ecology, a demography, and a geography that would be most favorable to the state and its ruler. What, in those circumstances, would you design?

Your task, crudely put, is to devise an ideal “state space”: that is to say, an ideal space of appropriation. Insofar as the state depends on taxes or rents in the largest possible sense of the term (foodstuffs, corvée labor, soldiers, tribute, tradable goods, specie), the question becomes: what arrangements are most likely to guarantee the ruler a substantial and reliable surplus of manpower and grain at least cost?

The principle of design must obviously hinge on the geographical concentration of the kingdom’s subjects and the fields they cultivate within easy reach of the state core. Such concentration is all the more imperative in premodern settings where the economics of oxcart or horse-cart travel set sharp limits to the distance over which it makes sense to ship grain. A team of oxen, for example, will have eaten the equivalent of the cartload of grain they are pulling before they have traveled 250 kilometers over flat terrain. The logic, albeit with different limits, is captured in an ancient Han proverb: “Do not make a grain sale over a thousand li”—415 kilometers.1 The non-grain-producing elites, artisans, and specialists at the state’s core must, then, be fed by cultivators who are relatively near. The concentration of manpower in the Southeast Asian context is, in turn, particularly imperative, and particularly difficult, given the historical low population-to-land ratio that favors demographic dispersal. Thus the kingdom’s core and its ruler must be defended and maintained, as well as fed, by a labor supply that is assembled relatively close at hand.

From the perspective of our hypothetical Colbert, wet-rice (padi, sawah) cultivation provides the ultimate in state-space crops. Although wet-rice cultivation may offer a lower rate of return to labor than other subsistence techniques, its return per unit of land is superior to almost any other Old World crop. Wet rice thus maximizes the food supply within easy reach of the state core. The durability and relatively reliable yields of wet-rice cultivation would also recommend it to our Colbert. Inasmuch as most of the nutrients are brought to the field by the water from perennial streams or by the silt in the case of “flood-retreat agriculture,” the same fields are likely to remain productive for long periods. Finally, and precisely because wet rice fosters concentrated, labor-intensive production, it requires a density of population that is, itself, a key resource for state-making.2

Virtually everywhere, wet rice, along with the other major grains, is the foundation of early state-making. Its appeal to a hypothetical Colbert does not end with the density of population and foodstuffs it makes possible. From a tax collector’s perspective, grains have decisive advantages over, for example, root crops. Grain, after all, grows aboveground, and it typically and predictably all ripens at roughly the same time. The tax collector can survey the crop in the field as it ripens and can calculate in advance the probable yield. Most important of all, if the army and/or the tax collector arrive on the scene when the crop is ripe, they can confiscate as much of the crop as they wish.3 Grain, then, as compared with root crops, is both legible to the state and relatively appropriable. Compared to other foodstuffs, grain is also relatively easy to transport, has a fairly high value per unit of weight and volume, and stores for relatively long periods with less spoilage, especially if it is left unhusked. Compare, for example, the relative value and perishability of a cartload of padi, on the one hand, and a cartload of, say, potatoes, cassava, mangoes, or green vegetables. If Colbert were called on to design, from scratch, an ideal state crop, he could hardly do much better than irrigated rice.4

No wonder, then, that virtually all of the premodern state cores in Southeast Asia are to be found in ecological settings that were favorable to irrigated rice cultivation. The more favorable and extensive the setting, the more likely a state of some size and durability would arise there. States, it should be emphasized, did not typically, at least until the colonial era, construct these expanses of padi fields, nor did they play the major role in their maintenance. All the evidence points to the piecemeal elaboration of padi lands by kinship units and hamlets that built and extended the small diversion dams, sluices, and channels required for water control. Such irrigation works often predated the creation of state cores and, just as frequently, survived the collapse of many a state that had taken temporary advantage of its concentrated manpower and food supply.5 The state might batten itself onto a wet-rice core and even extend it, but rarely did the state create it. The relationship between states and wet-rice cultivation was one of elective affinity, not one of cause and effect.

The realpolitik behind this elective affinity is evident in the fact that “for European governors and Southeast Asian rulers alike, large settled populations supported by abundant amounts of food were seen as the key to authority and power.”6 Land grants in ninth- and tenth-century Java, for which we have inscriptional evidence, were made on the understanding that the recipients would clear the forest and convert shifting, swidden plots into permanent irrigated rice fields (sawah). The logic, as Jan Wisseman Christie notes, is that “sawah … had the effect of anchoring populations and increasing their visibility, and making the size of the crop relatively stable and easy to calculate.”7 No effort was spared, as we shall see in more detail, to attract and hold a population in the vicinity of the court and to require it to plant padi fields. Thus Burmese royal edicts of 1598 and 1643, respectively, ordered that each soldier remain in his habitual place of residence, near the court center, and required all palace guards not on duty to cultivate their fields.8 The constant injunctions against moving or leaving the fields fallow are, if we read such edicts “against the grain,” evidence that achieving these goals met with a good deal of resistance. When such goals were approximated, however, the result was an impressive “treasury” of manpower and grain at the monarch’s disposal. Such seems to have been the case at Mataram, Java, in the mid-seventeenth century, when a Dutch envoy remarked on “the unbelievably great rice fields which are all around Mataram for a day’s travel, and with them innumerable villages.” The resources of manpower at the core were not only crucial for food production; they were militarily essential to the defense and expansion of the state against its rivals. The decisive advantage of agrarian states of this kind against their maritime competitors appears to have rested precisely on their numerical superiority in fielding soldiers.

The friction of terrain set up sharp, relatively inflexible limits to the effective reach of the traditional agrarian state. Such limits were essentially fixed, as noted earlier, by the difficulty of transporting bulk foodstuffs. Assuming level terrain and good roads, the effective state space would have become tenuous indeed beyond a radius of three hundred kilometers. In one sense, the difficulty of moving grain long distances, compared with the relative ease of human pedestrian travel, captures the essential dilemma of Southeast Asian statecraft before the late nineteenth century. Provisioning the state’s core population with grain ran up against the intractable limits of distance and harvest fluctuations, while the population sequestered to plant that grain found it all too easy to walk beyond the reach of state control. Put another way, the friction and inefficiencies of the oxcart worked to constrict the food supply available to the state core, whereas the relatively frictionless movement of its subjects by foot—a movement the premodern state could not easily prevent—threatened to deprive it of grain growers and defenders.9

The stark statistical facts of premodern travel and transportation make the friction-of-distance comparisons between water and land abundantly clear. As a rule of thumb, most estimates of travel by foot, assuming an obligingly flat, dry terrain, converge around an average of twenty-four kilometers (fifteen miles) a day. A strong porter carrying a thirty-six-kilogram (eighty-pound) load might move nearly as far under very favorable conditions. Once the terrain becomes more rugged or the weather more challenging (or both), however, this optimistic figure is dramatically reduced. The calculus is slightly modified in premodern Southeast Asia, and particularly in warfare, by the use of elephants, which could carry baggage and negotiate difficult terrain, but their numbers were modest and no military campaign depended essentially on them.10

What might be called state travel through difficult hilly terrain was considerably slower. One of the rare surviving documents (860 CE) from the Tang dynasty’s expansion into the mountainous areas of mainland Southeast Asia begins with the critical military information about travel times, expressed in day-stages, between population centers that were nodes of imperial control.11 A millennium later, the same preoccupation is apparent. A representative example is the trip made by Lieutenant C. Ainslie in January (the dry season) 1892 through the eastern Shan states to assess the political loyalties of the chiefs and to survey routes of march. He was accompanied by one hundred military policemen, five Europeans, and a large number of pack mules, together with their drivers. He used no wheeled transport, presumably because the tracks were too narrow. Ainslie prospected two parallel routes between Pan Yang and Mon Pan, a nine-day trip. He reported on the difficulty of each day’s stage and the number of rivers and streams that had to be crossed, noting in passing that the route was “impassible in the rains.”12 The daily average distance covered was barely more than thirteen kilometers (eight miles), with considerable daily variation: a maximum of less than twenty kilometers and a minimum of barely seven.

A bullock cart can, of course, carry anywhere from seven to ten times (240–360 kilograms) the load of a fit individual porter.13 Its movements, however, are both slower and more restricted. Where the porter requires only a footpath, the bullock cart requires a broader track. In some terrain, this is impossible; anyone familiar with the deeply rutted cart tracks in backcountry Burma will appreciate how slow and laborious the going is even when such travel is possible. For a trip of any length the carter must either carry his own fodder, thereby reducing the payload, or adjust the route to take advantage of fodder growing along it.14 Until a century or two ago, even in the West, the overland transport of bulk commodities “has been subject to narrow and essentially inflexible limits.”15

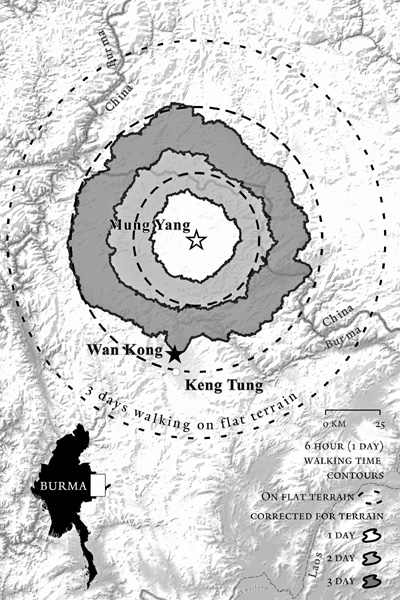

These geographical givens of movement of people and goods set limits to the reach of any landward state. Extrapolating from a more generous estimate of 32 kilometers a day by foot, F. K. Lehman estimates that the precolonial state’s maximum size could not have been much more than 160 kilometers in diameter, although Mataram in Java was considerably broader. Assuming a court roughly in the center of a circular kingdom with a diameter of, say, 240 kilometers, the distance to the kingdom’s edge would be 120 kilometers.16 Much beyond this point, even in flat terrain, state power would fade, giving way to the sway of another kingdom or to local strongmen and/or bandit gangs. (See map 3 for an illustration of the effect of terrain on effective distances.)

Water transport, however, is the great premodern exception to these limits. Navigable water nullifies much of the friction of distance. Wind and currents make it possible to move bulk goods in large quantities over distances that are inconceivable using carts. In thirteenth-century Europe, according to one calculation, shipping costs by sea were a mere 5 percent of the cost by land. The disparity was so massive as to confer a large strategic and trade advantage on any kingdom near a navigable waterway. Most Southeast Asian precolonial states of any appreciable size had easy access to the sea or to a navigable river. In fact, as Anthony Reid notes, the capitals of most Southeast Asian states were located at river junctions where oceangoing ships had to transfer their cargoes to smaller craft plying the upstream reaches of the river. The location of nodes of power coincided largely with the intersecting nodes of communication and transportation.17

The key role of water transportation before the construction of railroads is evident in the great economic significance of canals, where the draft power was often the same—horses, mules, oxen—but the reduction of friction made possible by barges moving over water allowed for huge gains in efficiency. River or sea transportation takes advantage of “routes of least friction,” of least geographical resistance, and thereby vastly extends the distances over which food supplies, salt, arms, and people can be exchanged. In epigrammatic form, we could say that “easy” water “joins,” whereas “hard” hills, swamps, and mountains “divide.”

Before the distance-demolishing technology of railroads and all-weather motor roads, land-bound polities in Southeast Asia and Europe found it extremely difficult, without navigable waterways, to concentrate and then project power. As Charles Tilly has noted, “Before the later nineteenth century, land transport was so expensive everywhere in Europe that no country could afford to supply a large army or big city with grain and other heavy goods without having efficient water transport. Rulers fed major inland cities such as Berlin and Madrid only at great effort and great cost to their hinterlands. The exceptional efficiency of waterways in the Netherlands undoubtedly gave the Dutch great advantages at peace and war.”18

The daunting military obstacles presented by travel over very rugged terrain, even in the mid-twentieth century, was never more evident than in the conquest of Tibet by the China’s People’s Liberation Army in 1951. Tibetan delegates and party representatives who signed the agreement in Beijing traveled back to Lhasa via “the quicker route”: namely by sea to Calcutta, then by train and horseback through Sikkim. Travel from Gongtok, Sikkim, to Lhasa alone took sixteen days. Within six months the PLA advance force in Lhasa was in danger of starving, and three thousand tons of rice was dispatched to them, again by ship to Calcutta and thence by mule over the mountains. Food came as well from Inner Mongolia to the north, but this required the astounding mobilization of twenty-six thousand camels, more than half of whom perished or were injured en route.19

Map 3. The striking constriction of state space imposed by rugged landscape may be illustrated by a map that compares walking times from a central place, depending on the difficulty of the terrain. Here we have selected Mung (Muang) Yang, a Shan town near the Burma-Chinese border, for illustrative purposes. The walking-time isolines shown here are based on Waldo Tobler’s “hiker function,” an algorithm that estimates the rate of travel possible based upon the slope at any given point on the landscape. These isolines show the travel distance possible assuming a six-hour walking day. The travel distances possible on flat terrain, based upon the Tobler algorithm, are shown in dotted lines for comparison. Setting out from Mung Yang, a traveler takes three days to cover the distance that, were the land flat, one could cover in a day and a half or two days. Travel is more difficult to the south and northwest than to the east. If we assume that the span of control varies directly with the ease of travel, than the total area under control of a hypothetical statelet centered on Mung Yang would be less than one-third of what it might be over level terrain.

The standard modern maps, in which a kilometer is a kilometer no matter what the terrain or body of water, are therefore profoundly misleading in this respect. Settlements that may be three hundred or four hundred kilometers distant over calm, navigable water are far more likely to be linked by social, economic, and cultural ties than settlements a mere thirty kilometers away over rugged, mountainous terrain. In the same fashion, a large plain that is easily traversed is far more likely to form a coherent cultural and social whole than a small mountainous zone where travel is slow and difficult.

Were we to require a map that was more indicative of social and economic exchange, we would have to devise an entirely different metric for mapmaking: a metric that corrected for the friction of terrain. Before the mid-nineteenth century revolution in transportation, this might mean constructing a map in which the standard unit was a day’s travel by foot or oxcart (or by sailing vessel). The result, for those accustomed to standard, as-the-crow-flies maps, would look like the reflection in a fairground funhouse mirror.20 Navigable rivers, coastlines, and flat plains would be massively shrunken to reflect the ease of travel. Difficult-to-traverse mountains, swamps, marshes, and forests would, by contrast, be massively enlarged to reflect travel times even though the distances, as the crow flies, might be quite small. Such maps, however strange to the modern eye, would be far superior guides to contact, culture, and exchange than the ones to which we have grown accustomed. They would also, as we shall see, help demarcate the sharp difference between a geography more amenable to state control and appropriation (state space) and a geography intrinsically resistant to state control (nonstate space).

A map in which the unit of measurement is not distance but the time of travel is, in fact, far more in accord with vernacular practices than the more abstract, standardized concept of kilometers or miles. If you ask a Southeast Asian peasant how far it is to the next village, say, the answer will probably be in units of time, not of linear distance. A peasant quite familiar with watches might answer “about half an hour,” and an older farmer, less familiar with abstract time units, might reply in vernacular units, “three rice-cookings” or “two cigarette-smokings”—units of duration known to all, not requiring a wristwatch. In some older, precolonial maps, the distance between any two places was measured by the amount of time it took to travel from one to the other.21 Intuitively this makes obvious sense. Place A may be only twenty-five kilometers from place B. But depending on the difficulty of travel, it could be a two-day trip or a five-day trip, something a traveler would most surely want to know. In fact, the answer might vary radically depending on whether one was traveling from A to B or from B to A. If B is in the plains and A is high in the mountains, the uphill trip from B to A is sure to be longer and more arduous than the downhill trip from A to B, though the linear distance is the same.

A friction of distance map allows societies, cultural zones, and even states that would otherwise be obscured by abstract distance to spring suddenly into view. Such was the essential insight behind Fernand Braudel’s analysis of The Mediterranean World. Here was a society that maintained itself by the active exchange of goods, people, and ideas without a unified “territory” or political administration in the usual sense of the term.22 On a somewhat smaller scale, Edward Whiting Fox argues that the Aegean of classical Greece, though never united politically, was a single, social, cultural, and economic organism, knit together by thick strands of contact and exchange over easy water. The great “trading-and-raiding” maritime peoples, such as the Viking and Normans, wielded a far-flung influence that depended on fast water transport. A map of their historical influence would be confined largely to port towns, estuaries, and coastlines.23 Vast sea spaces between these would be small.

The most striking historical example of this phenomenon was the Malay world—a seafaring world par excellence—whose cultural influence ran all the way from Easter Island in the Pacific to Madagascar and the coast of Southern Africa, where the Swahili spoken in the coastal ports bears its imprint. The Malay state itself, in its fifteenth- and sixteenth-century heyday, could fairly be called, like the Hanseatic League, a shifting coalition of trading ports. The elementary units of statecraft were ports like Jambi, Palembang, Johor, and Melaka, and a Malay aristocracy shuffled between them depending on political and trade advantages. Our landlocked sense of a “kingdom” as consisting of a compact and contiguous territory makes no sense when confronted with such maritime integration across long distances.

An agrarian kingdom is typically more self-contained than a maritime kingdom. It disposes of reserves of food and manpower close to home. Nevertheless, even agrarian kingdoms are far from self-sufficient; they depend for their survival on products outside their direct control: hill and coastal products such as wood, ores, protein, manure from pastoralists’ flocks, salt, and so on. Maritime kingdoms are even more dependent on trade routes to supply their necessities, including, especially, slaves. For this reason, there are what might be called spaces of high “stateness” that do not depend on local grain production and manpower. Such locations are strategically situated to facilitate the control (by taxes, tolls, or confiscation) of vital trade products. Long before the invention of agriculture, those societies controlling key deposits of obsidian (necessary for the best stone tools) occupied a privileged position in terms of exchange and power. More generally there were certain strategic choke points on land and water trade routes, the control of which might confer decisive economic and political advantages. The Malay trading port is the classical example, typically lying athwart a river junction or estuary, allowing its ruler to monopolize trade in upstream (hulu) export products and similarly to control the hinterland’s access to trade goods from downstream (hilir) coastal and international commerce. The Straits of Malacca were, in the same fashion, a choke point for long-distance trade between the Indian Ocean and China and thus a uniquely privileged space for state-making. On a smaller scale, innumerable hill kingdoms sat astride important caravan routes for salt, slaves, and tea, among other goods. They waxed and waned depending on the vagaries of world trade and commodity booms. Like their larger Malay cousins, they were, at their most peaceful, “toll” states.

Positional advantages of this kind are only partly a matter of the terrain and sea lanes. They are, especially in the modern era, historically contingent on revolutions in transport, engineering, and industry: for example, rail and road junctions, bridges and tunnels, coal, oil, and natural gas deposits.

Our crude first approximation of state space as the concentration of grain production and manpower in a manageable space must then be modified. The distance-demolishing properties of navigable water routes and the existence of nodes of power represented by choke points and strategic commodities can compensate for deficiencies in grain and manpower close at hand, but only to a point. Without sufficient manpower, it is frequently difficult for toll states to hold onto the site that confers a positional advantage. In the case of a showdown, agrarian states have generally been able to prevail over maritime or “trade-route” states by force of numbers. The disparity is highlighted by Barbara Andaya’s comparison of the Vietnamese Trinh (an agrarian state) and Johore (a maritime state) at the beginning of the eighteenth century: “The point can be made clearly by comparing the armed forces of Johore, the most prestigious of the Malay States, but one without any agrarian base, with those of the Trinh. In 1714, the Dutch estimated that Johor could bring into battle 6,500 men and 233 vessels of all types. In Vietnam, by contrast, the Nguyen army was tallied at 22,740 men, including 6,400 marines and 3,280 infantry.”24 The earliest cautionary tale of maritime-state vulnerability is, of course, Thucydides’ Peloponnesian War, in which a resolutely maritime Athens is, finally, undone by its more agrarian rivals, Sparta and Syracuse.

State-building in precolonial mainland Southeast Asia was powerfully constrained by geography. Here, in a rough and ready way, I shall attempt to outline those major constraints and their effects on the location, maintenance, and power dynamics of such states.

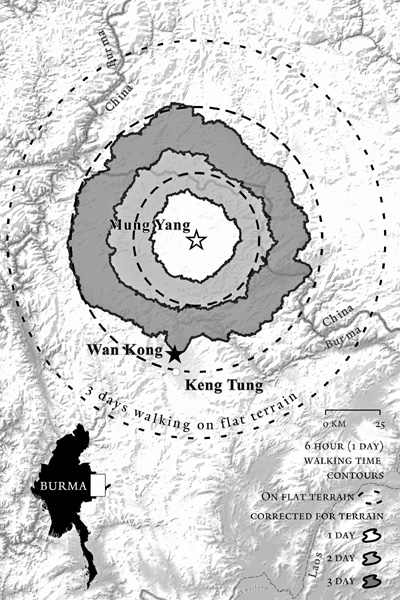

The necessary, but by no means sufficient, condition for the rise of a substantial state was the existence of a large alluvial plain suitable for the cultivation of irrigated rice and hence capable of sustaining both a substantial and concentrated population. Unlike maritime peninsular Southeast Asia, where the ease of movement over the calm waters of the Sunda Shelf permitted the coordination of a far-flung thalassocracy on the order of Athens, mainland states had to contend with far higher levels of geographical friction. Because of the generally north-south direction of mountain ranges and major rivers in the region, virtually all of the classical states were to be found along the great north-south river systems. They were, moving from west to east, the Burman classical states along the Irrawaddy near its confluence with the Chindwin (Pagan, Ava, Mandalay) or along the Sittang not far to the east (Pegu, Toungoo); the Thai classical state (Ayutthaya and, much later, Bangkok, along the Chao Phraya); the Khmer classical state (Angkor and its successors) near the great lake of Tonle Sap, a tributary of the Mekong; and finally, the early heartland of the Kinh (Trinh) classical state along the Red River in the vicinity of Hanoi.

The common denominator here is that all such states have been created near navigable water courses, but above the flood plain, where a flat, arable plain and perennial streams made wet-rice cultivation possible. It is striking that none of the early mainland states was located in the delta of a major river. Such delta regions—the Irrawaddy, the Chao Phraya, and Mekong—were settled in force and planted to wet rice only in the early twentieth century. The reasons for their late development, apparently, are that 1) they required extensive drainage works to be made suitable for rice cultivation, 2) they were avoided because they were malarial (especially when newly cleared), and 3) the annual flooding was unpredictable and often devastating.25 This bold generalization, however, needs to be clarified and qualified. First, the political, economic, and cultural influence emanating from such centers of power, as Braudel would have predicted, spread most easily when least impeded by the friction of distance—along level terrain and navigable rivers and coastlines. Nothing illustrates this process more strikingly than the gradual, intermittent displacement of Cham and Khmer populations by the Vietnamese. This expansion followed the thin coastal strip southward, with the coast serving as a watery highway leading, eventually, all the way to the Mekong Delta and the trans-Bassac.

The economic reach of such state centers was almost always greater than their political reach. While their political control was limited by their degree of monopoly access to mobilized manpower and food supplies, their influence on trade might reach considerably farther. The friction of distance is at work here too; the greater the exchange value of a product vis-à-vis its weight and volume, the greater the distance over which it might be traded. Thus precious commodities such as gold, gemstones, aromatic woods, rare medicines, tea, and ceremonial bronze gongs (important prestige goods in the hills) linked peripheries to centers on the basis of exchange rather than political domination. On this basis, the geographical scope of certain forms of trade and exchange, requiring no bulk transport, was far more extensive than the comparatively narrow range within which political integration might be achieved.

I have thus far considered only the major classical states in mainland Southeast Asia. The key condition for state formation was present elsewhere as well: a potential heartland of irrigated rice cultivation that might constitute a “fully-administered territorial nucleus, having a court capital at its center.”26 The difference was purely a matter of scale. Where the heartland of irrigated rice was large and contiguous, it might, under the right conditions, facilitate the rise of a major state; where the heartland was modest, it might, also under the right conditions, give rise to a modest state. A state on this account would be a fortified town of, say, at least six thousand subjects plus nearby hill allies, situated on wet-rice plain and having, in theory at least, a single ruler. Scattered throughout mainland Southeast Asia, often at fairly high altitudes, one finds the agro-ecological conditions that favor state formation, usually on a more Lilliputian scale. Most such places were at one time or another the sites of small Tai statelets. More rarely, leagues or confederacies of such statelets might combine, briefly, to forge a more formidable state. State formation around wet-rice cores, large or small, was always contingent and, typically, ephemeral. One might emphasize with Edmund Leach the fact that “the riceland stayed in one place” and thus represented a potential ecological and demographic strong point, which a clever and lucky political entrepreneur might exploit to create a new, or revived, state space. Even a successful dynasty was by no means a Napoleonic state; it was rather a shaky hierarchy of nested sovereignties. To the degree that it held together, the glue was a prudent distribution of spoils and marriage alliances and, when necessary, punitive expeditions for which, in the final analysis, control over manpower was vital.

Map 4. Rivers and classical states of Southeast Asia: The coincidence of classical states with navigable water courses is the general rule, as the map illustrates. The Salween/Nu/Thanlwin River spawned only one classical state, Thaton, at its estuary. For much of its long course, the Salween runs through deep gorges and is not navigable. It is, solely for this reason, an exception. Keng Tung and Chiang Mai are also exceptions in the sense that neither is located close to a major navigable river. Each, however, commands a large, arable plain suitable for padi cultivation and hence for state-making.

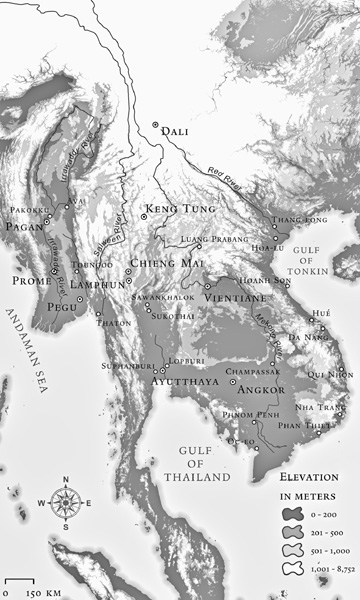

Our conception of what constituted precolonial Burma must therefore be adjusted according to these basic principles of appropriation and span of control. Under a robust, flourishing dynasty, “Burma,” in the sense of an effective political entity, consisted largely of wet-rice core areas within a few days’ march from the court center. Such wet-rice areas need not necessarily be contiguous, but they had to be relatively accessible to officials and soldiers from the center via trade routes or navigable waterways. The nature of the routes of access was itself crucial; an army on its way to collect grain or to punish a rebellious district had to provision itself en route. This meant locating a route of march through territory sufficiently rich in grain, draft animals, carts, and potential recruits for the army to sustain itself.

Thus marshes, swamps, and, especially, hilly areas, though they might be quite close to the court center, were generally not a part of “political, directly administered Burma.”27 Such hills and marshes were sparsely populated and, except in the case of a substantial plateau suitable for irrigated rice, their population practiced a form of mixed cultivation (dispersed swiddens for hill rice, root crops, foraging, and hunting) that was difficult to assess, let alone appropriate. Areas of this kind might have a tributary alliance with the court specifying the periodic renewal of oaths and the exchange of valuable goods, but they remained generally outside the direct political control of court officials. As a rule of thumb, hilly areas above three hundred meters in elevation were not a part of “Burma” proper. We must therefore consider precolonial Burma as a flatland phenomenon, rarely venturing out of its irrigation-adapted ecological niche. As Braudel and Paul Wheatley noted in general, political control sweeps readily across a flat terrain. Once it confronts the friction of distance, abrupt changes in altitude, ruggedness of terrain, and the political obstacle of population dispersion and mixed cultivation, it runs out of political breath.

Modern concepts of sovereignty make little sense in this setting. Rather than being visualized as a sharply delineated, contiguous territory following the mapmaking conventions for modern states, “Burma” is better seen as a horizontal slice through the topography, taking in most areas suitable for wet rice below three hundred meters and within reach of the court.28

Imagine a map constructed along these lines, designed to represent relative degrees of potential sovereignty and cultural influence. One way of visualizing how the friction of distance might work is to imagine yourself holding a rigid map on which altitudes were represented by the physical relief of the map itself. Further, let’s imagine that the location of each rice-growing core is marked by a reservoir of red paint filled to the very brim. The size of the reservoir of paint would be proportional to the size of the wet-rice core and hence the population it might accommodate. Now visualize tilting this map, now in one direction, now in another, successively. The paint as it spilled from each reservoir would flow first along level ground and along the lowland water courses. As you increased the angle at which the map was tilted, the red paint would flow slowly or abruptly, depending on the steepness of the terrain, to somewhat higher elevations.

Map 5. Elevation in central Burma: The “reach” of the precolonial state, at its most robust, stretched most easily along the low elevation plains and navigable river courses. All of the upper Burma kingdoms hugged the Irrawaddy above or below its confluence with the Chindwin. The Shan Hills to the east of Mandalay and Ava, though closer as the crow flies than the downriver towns of Pokokku and Magway, were outside the effective limits of the kingdom. The precolonial state also skirted the north-south Pegu-Yoma range of modest but rugged hills that bisected the rice plain. These hills remained effectively outside state control in the precolonial period, in much of the colonial period, and in independent Burma, where they were the redoubt of communist and Karen rebels until 1975. It is a striking example of how even relatively modest changes in the friction of terrain can impede state control.

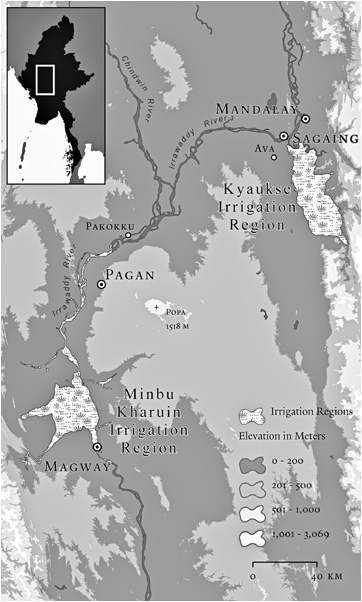

Map 6. Minbu Kharuin (K’à yaín) and Kyaukse irrigation works: These two main irrigation zones were the rice basket of precolonial states in upper Burma. The Minbu Kharuin irrigation works considerably predate the Pagan kingdom’s rise in the ninth century CE. These two rice cores formed the repository of manpower and grain necessary to state formation and its inevitable accompaniment, warfare. (The term k’à yaín— —often transliterated kharuin, means “district” and connotes a walled town, as in the famous “nine K’à yaín” making up classical Kyaukse. It is the equivalent in most respects of the Shan term maín—

—often transliterated kharuin, means “district” and connotes a walled town, as in the famous “nine K’à yaín” making up classical Kyaukse. It is the equivalent in most respects of the Shan term maín— :—or the Thai muang.) Outside these two zones, on the plain, there was rain-fed, arable land, but the yields were neither as reliable nor as bounteous as those from the irrigated lands. In the north salient of the Pegu Yoma—Mount Popa and the elevated hills extending from it—population and agricultural production were even sparser. And the population and produce present were difficult to appropriate.

:—or the Thai muang.) Outside these two zones, on the plain, there was rain-fed, arable land, but the yields were neither as reliable nor as bounteous as those from the irrigated lands. In the north salient of the Pegu Yoma—Mount Popa and the elevated hills extending from it—population and agricultural production were even sparser. And the population and produce present were difficult to appropriate.

The angle at which you had to tilt the map to reach particular areas would represent, very roughly, the degree of difficulty the state would face in trying to extend its control that far. If we assume that the intensity of the red fades both in proportion to the distance it has traveled and the altitude it has attained, we have an approximation, again very roughly, of the diminishing influence and control or, alternatively, the relative cost of establishing direct political control in such areas. At higher elevations, the red would give way to white; if the terrain there was both steep and high, the transition would be quite abrupt. From above, depending on the number of hilly areas near the court center, this depiction of sovereignty would reveal a number of irregular white spots against a dark or pale red background. The population that inhabited the white blotches, although it might often be in a tributary relation to the court center, was rarely if ever directly ruled. If political control weakened suddenly before the daunting hills, cultural influence weakened as well. Language, settlement patterns, kinship structure, ethnic self-identification, and subsistence practices in the hills were distinctly different from those in the valleys. For the most part, hill peoples did not follow valley religions. Whereas the valley Burmans and Thais were Theravada Buddhists, hill peoples were, with some notable exceptions, animist and, in the twentieth century, Christians.

The color scheme of this fantasy friction-of-distance map would also offer a rough and ready guide to patterns of cultural and commercial, but not political, integration. Where the red color spreads with the least resistance, along river courses and flat plains, there one is likely to find more homogeneity in religious practices, language dialects, and social organization as well. Abrupt cultural and religious changes are likely to occur at the same places where there is, as with a mountain range, an abrupt increase in the friction of distance. If the map could also show, like a time-lapse photograph, the volume of human and commercial traffic across a space as well as the relative ease of movement, we would have an even better proxy for the likelihood of social and cultural integration.29

Our metaphorical map, like any map, though it serves to foreground the relationships we wish to highlight, obscures others. It cannot easily account, in these terms, for the friction of distance represented, say, by swamps, marshes, malarial zones, mangrove coasts, and thick vegetation. Another caution concerns the “pot of paint” at the state core. It is purely hypothetical; it represents the plausible reach of influence of a vigorous, ambitious state core under the most favorable conditions. Few state cores even came close to realizing this degree of sway over their hinterlands.

None of these state cores, large or small, had the terrain to itself. Each existed as one unit among a galaxy of waxing and waning contending centers. Before colonial domination and the codification of the modern territorial state vastly simplified the terrain, the sheer numbers of state centers, mostly Lilliputian, was bewildering. Leach was not exaggerating when he noted that “practically every substantial township in ‘Burma’ claims a history of having been at one time or another the capital of a ‘kingdom’ the alleged frontiers of which are at once both grandiose and improbable.”30

How might we represent, again schematically, this plurality of state centers? One alternative is to invoke the Sanskritic term mandala (“circle of kings”), much used in Southeast Asia, in which the influence of a ruler, often claiming divine lineage, emanates from a court center, almost always located on a rice plain, out into the surrounding countryside. In theory, he rules over lesser kings and chiefs who recognize his claim to spiritual and temporal authority. The anachronistic metaphor of a light bulb with varying degrees of illumination to represent the charisma and sway of a ruler, first suggested by Benedict Anderson, captured two essential features of mandala-style political centers.31 Its dimming suggested the gradual diminution of power, both spiritual and temporal, with distance from the center, and its diffuse glow avoided any modern assumption of “hard” boundaries within which 100 percent sovereignty prevailed and beyond which it disappeared altogether.

In figure 1 I attempt to depict some of the striking complexities of sovereignty in a plural mandala system. In order to do so, I have represented a number of mandala (negara, muang, maín, k’à yaín) by fixed circles with power concentrated at the center and fading gradually to zero at the outer circumference. This requires us, for the moment, to overlook the massive influence of terrain. We assume, in effect, a plain as flat as a pancake. Burmese authorities in the seventeenth century also made such simplifying assumptions in their own territorial order: a province was imagined as a circle and specified to have an administrative radius of exactly one hundred tiang (one tiang equals 3¼ kilometers), a big town a radius of ten tiang, a medium town five tiang, and a village two and a half tiang.32 The reader should imagine how geographical irregularities—say, a swamp or rugged terrain—would truncate these circular shapes or how a navigable river might extend their reach along the waterway. More egregious, still, the very fixity of the representation of space completely ignores the radical temporal instability of the system: the fact that “centers of spiritual authority and political power shifted endlessly.”33 The reader should rather imagine these centers as sources of light that blaze, go faint, and are in time extinguished altogether, while new sources of light, points of power, suddenly appear and glow brighter.

Each circle represents a kingdom; some are smaller, others are larger, but the power of each recedes as one moves to the periphery, as represented by the diminishing density of icons within each mandala. The purpose of this rather facile graphic is merely to illustrate some of the complexities of power, territory, and sovereignty in precolonial mainland Southeast Asia, worked out in considerably more detail by Thongchai Winichakul.34 In theory, the lands within a mandala’s sway provided an annual tribute (which might be reciprocated by a gift of equal or greater value) and were obliged to send troops, carts, draft animals, food, and other supplies when required. And yet, as the graphic indicates, many areas fell within the ambit of more than one overlord. Where dual sovereignty, as in the area D/A, was located at the periphery of both kingdoms, it might well represent a case of mutually canceling, weak sovereignty, affording local chiefs and their following great autonomy in this buffer area. Where it affected much of the kingdom, as in B/A or A/C, it might be the occasion of competing exactions and/or punitive raids by the center on noncompliant, disloyal villages. Many hill peoples and petty chieftaincies strategically manipulated the situation of dual sovereignty, quietly sending tributary missions to two overlords and representing themselves to their own tributaries as independent.35 Calculations of tribute were not an allor-nothing affair, and the endless strategic choices of what to send, when to send it, when to delay, when to withhold manpower and supplies were at the very center of this petty statecraft.

1. Schema of mandalas as fields of power

Outside the central core of a kingdom, dual or multiple sovereignty or, especially at higher elevations, no sovereignty, was less an anomaly than the norm. Thus Chaing Khaeng, a small town near the current borders of Laos, Burma, and China, was tributary to Chiang Mai and Nan (in turn, tributary to Siam) and to Chiang Tung/Keng Tung (in turn, tributary to Burma). The situation was common enough that small kingdoms were often identified as “under two lords” or “under three lords” in the Thai language and its Lao dialect, and a “two-headed bird” in the case of nineteenth-century Cambodia’s tributary relationship to both Siam and Dai Nan (Vietnam).36

Unambiguous, unitary sovereignty, of the kind that is normative for the twentieth-century nation-state, was rare outside a handful of substantial rice-growing cores, whose states were, themselves, prone to collapse. Beyond such zones, sovereignty was ambiguous, plural, shifting, and often void altogether. Cultural, linguistic, and ethnic affiliations were, likewise, ambiguous, plural, and shifting. If we add to this observation what we understand about the friction of terrain and altitude in projecting political power, we can begin to appreciate the degree to which much of the population, and most especially the hill peoples, were, though never untouched by the court centers of the region, hardly under their thumb.

Even the most robust kingdom, however, shrank virtually to the ramparts of its palace walls once the monsoon rains began in earnest. The Southeast Asian state, in its precolonial mandala form, its colonial guise, and, until very recently, as a nation-state, was a radically seasonal phenomenon. On the mainland, roughly from May through October, the rains made the roads impassable. The traditional period for military campaigns in Burma was from November to February; it was too hot to fight in March and April, and from May through much of October it was too rainy.37 Not only were armies and tax collectors unable to move far in any force, but travel and trade were reduced to a trivial proportion of their dry-season volume. To visualize what this meant, we would have to consider our mandala map as a dry-season representation. For the rainy season, we would have to shrink each kingdom to something like a quarter to an eighth of its size, depending on the terrain.38 As if some semiannual flood tide virtually marooned the state as the rains began and then released its watery grip when they stopped, state space and nonstate space traded places with meteorological regularity. A hymn of praise to a fourteenth-century Javanese ruler notes the periodicity of rule: “Every time at the end of the cold season [when it is quite dry] he sets out to roam through the countryside.… He shows the flag especially in remote areas.… He displays the splendor of his court.… He receives homage from all and sundry, collects tribute, visits village elders, checks land registers and examines public utilities such as ferries, bridges and roads.”39 Subjects knew roughly when to expect their ruler. They also knew roughly when to expect armies, press-gangs, military requisitions, and the destruction of war. War, like fire, was a dry-season phenomenon. Military campaigns, such as the several invasions of Siam by the Burmese, always began after the end of the rainy season, when the tracks were again passable and the crops ripening.40 Any thorough examination of traditional state-making would have to give almost as large a place to weather as to pure geography.

Colonial regimes, though they worked mightily to construct all-weather roads and bridges, were thwarted in much the same way as the indigenous states they replaced. In the long, arduous campaign to occupy upper Burma, the progress made by colonial troops (mostly from India) in the dry season was often undone by the rains and, it seems, by the diseases of the wet season as well. An account of the effort in 1885 to clear Minbu, in upper Burma, of rebels and bandits, revealed that the rains forced a withdrawal of British troops: “And by the end of August the whole of the western part of the district was in the hands of the rebels and nothing remained to us but a narrow strip along the river-bank. The rains and the deadly season which succeeds them in the water-logged country at the foot of the Yoma [Pegu-Yoma mountain range] … prevented extended operations from being undertaken before the end of the year [again the dry season].”41 In the steep, mountainous terrain along the Thai border where the Burmese army today fights a war without mercy against its ethnic adversaries, the rainy season remains a major handicap to regular armed forces. The typical offensive “window” for Burmese troops has been exactly that of the former kings of Pagan and Ava: November through February. Helicopters, forward bases, and new communications gear have allowed the regime to mount, for the first time, wet-season offensives. Nevertheless, the capture of the last major Karen base on Burmese territory took place on January 10, 1995, just as the earlier pattern of seasonal warfare would have dictated.

For those wishing to keep the state at arm’s length, inaccessible mountain redoubts constituted a strategic resource. A determined state might mount a punitive expedition, burning houses and aboveground crops, but long-term occupation was beyond its reach. Unless it had hill allies, a hostile population need only wait for the rains, when supply lines broke down (or were easier to cut) and the garrison was faced with starvation or retreat.42 Thus the physical, coercive presence of the state in the remotest, hilly areas was episodic, often to the vanishing point. Such areas represented a reliable zone of refuge for those who lived there or who chose to go there.