The pagoda is finished; the country is ruined.

—Burmese proverb

When an expanding community, in taking over new territory, expels the old occupants (or some of them), instead of incorporating them into its own fabric, those who retreat may become, in the new territory into which they spread, a new kind of society.

—Owen Lattimore, The Frontier in History

The 9/11 Commission, reporting on its investigation into the attacks on the World Trade Center in New York in 2001, called attention to the novel location of the terrorist threat. Rather than coming from a hostile nation-state, it came from what the commission called “sanctuaries” in “the least governed, most lawless,” “most remote,” “vast un-policed regions,” in “very difficult terrain.”1 Particular sanctuaries, such as the Tora Bora and Shah-i-Kot regions along the Pakistan-Afghan border and the “hard to police” islands of the southern Philippines and Indonesia, were singled out. The commission was quite aware that it was the combination of geographical remoteness, forbidding terrain, and, above all, the relative absence of state power that made such areas recalcitrant to the exercise of power by the United States or its allies. What they failed to note was that much of the existing population in such areas of sanctuary were there precisely because these areas had historically been an area of refuge from state power.

Just as a relatively stateless, remote region provided sanctuary for Osama bin Laden and his entourage, so has the vast mountainous region of mainland Southeast Asia we have called Zomia provided an historical sanctuary for state-evading peoples. Providing that we take a long view—and by “long” I mean fifteen hundred to two thousand years—it makes best sense to see contemporary hill peoples as the descendants of a long process of marronnage, as runaways from state-making projects in the valleys. Their agricultural practices, their social organization, their governance structures, their legends, and their cultural organization in general bear strong traces of state-evading or state-distancing practices.

This view of the hills as peopled, until very recently, by a process of state-evading migration is in sharp contrast to an older view that is still part of the folk beliefs of valley people. This older view saw hill people as an aboriginal population that had failed, for one reason or another, to make the transition to a more civilized way of life: specifically, to settled, wet-rice agriculture, lowland religion, and membership (as subject or citizen) in a larger political community. Hill peoples, in the most stringent version of this perspective, were an unalterably alien population living in a kind of highland cultural sump, and hence unsuitable prospects for cultural advancement. On the more charitable view that currently prevails, such populations are thought to have been “left behind” culturally and materially (perhaps even “our living ancestors”), and ought, therefore, to be made the object of development efforts to integrate them into the cultural and economic life of the nation.

If, on the contrary, the population of Zomia is more accurately seen as a complex of populations that have, at one time or another, elected to move outside the easy reach of state power, then the evolutionary sequence implied by the older view is untenable. Hilliness instead becomes largely a state effect, the defining trait of a society created by those who have, for whatever reason, left the realm of direct state power. As we shall see, such a view of hill peoples as state-repelling societies—or even antistate societies—makes far more sense of agricultural practices, cultural values, and social structure in the hills.

The overarching logic of the demographic peopling of the hills, despite the murkiness and large gaps in the evidence for earlier periods, is reasonably certain. The rise of powerful valley padi states with demographic and military superiority over smaller societies led to a double process of absorption and assimilation on the one hand and extrusion and flight on the other. Those absorbed disappeared as distinctive societies, though they lent their cultural color to the amalgam that came to represent valley culture. Those extruded, or fleeing, tended to head for more remote sanctuaries in the hinterlands, often at higher altitudes. The zones of refuge to which they repaired were not by any means empty, but, over the long haul, the demographic weight of the state-evading migrants and their descendants tended to prevail. Seen from a long historical perspective, the process was characterized by fits and starts. Periods of dynastic peace and expanding commerce as well as periods of successful imperial expansion enlarged the population living under the aegis of state authority. The standard narrative of a “civilizing process,” though hardly as benign or voluntary as its rosier versions imply, might be said to characterize such eras. At times of war, crop failure, famine, crushing taxation, economic contraction, or military conquest, however, the advantages of a social existence outside the reach of the valley state were far more alluring. The reflux of valley populations into those areas, often the hills, where the friction of terrain provided asylum from the state, played a major role in the peopling of Zomia and in the social construction of state-repelling societies. Migrations of this kind have been occurring on both small and large scales for the last two millennia. Each new pulse of migrations encountered those who had come earlier and those long established in the hills. The process of conflict, amalgamation, and reformulation of identities in this little-governed space accounts in large measure for the ethnic complexity of Zomia. Because it found no legitimate place in the self-representations of valley-state texts, this process was rarely chronicled. Until the twentieth century, however, it was very common. Even today, as we shall see, it continues on a smaller scale.

One state above all the others was the propulsive force setting multitudes of people in motion and absorbing others. From at least the expansion of the Han Dynasty southward to the Yangzi (202 BCE-22O CE), when the Chinese state first became a great agrarian empire, and continuing, in fits and starts, all the way to the Qing and its successors, the Republic and the People’s Republic, populations seeking to evade incorporation have moved south, west, and then southwest into Zomia—Yunnan, Guizhou, Guangxi, and Southeast Asia proper. Other padi states, established later, mimicked the same process on a smaller scale and occasionally posed a strategic obstacle to Chinese expansion. The Burmese, Siamese, Trinh, and Tibetan states were the most prominent, but still minor-league states, whereas a good many even smaller padi states that played, for a time, a similar role—Nan Chao, Pyu, Lamphun/Haripunjaya, and Kengtung, to name only a few—have passed into history. As manpower machines capturing and absorbing population, they also, in the same fashion, disgorged state-fleeing populations to the hills and created their own “barbarian” frontier.

The importance of the hills as sanctuary from the many burdens imposed on state subjects has not gone unnoticed. As Jean Michaud has observed, “To some extent montagnards can be seen as refugees displaced by war and choosing to remain beyond the direct control of state authorities, who sought to control labor, tax productive resources, and secure access to populations from which they could recruit soldiers, servants, concubines, and slaves. This implies that montagnards have always been on the run.”2 Michaud’s observation can, if examined in the light of the historical, agro-ecological, and ethnographic evidence, provide a powerful lens through which to understand Zomia as a vast state-resistant periphery. The purpose of this chapter and the following two is to outline in broad strokes an argument for the resolving power of this particular lens.

The perspective we propose for understanding Zomia is not novel. A similar case has been made for many regions of the world, large and small, where expanding kingdoms have forced threatened populations to choose between absorption and resistance. Where the threatened population was itself organized into state forms, resistance might well take the shape of military confrontation. If defeated, the vanquished are absorbed or migrate elsewhere. Where the population under threat is stateless, its choices typically boil down to absorption or flight, the latter often accompanied by rearguard skirmishes and raids.3

An argument of just this kind for Latin America was made nearly thirty years ago by Gonzalo Aguirre Beltrán. Under the title Regions of Refuge, he argued that something like a preconquest society remained in remote, inaccessible regions far from the centers of Spanish control. Two considerations determined their location. First, they were regions of little or no economic value to the Spanish colonizers. Second, they were geographically forbidding areas where the friction of distance was particularly high. Aguirre Beltrán pointed to areas of “rugged countryside isolated from transportation routes by physical barriers, with a harsh landscape and scanty agricultural yields.” Three environments that met these conditions were deserts, tropical jungles, and mountain ranges, all of which were “hostile or inaccessible to human movement.”4 In Aguirre Beltrán’s formulation, the indigenous population was largely a remnant not so much pushed into, or fleeing into, such zones as left alone because it was of no economic interest to the Spanish and posed no military threat.

Aguirre Beltrán allows for the fact that some of the indigenous population was forced by Spanish land grabs to abandon the fields and retreat to the safety of those regions that were least desired by Ladino settlers.5 Subsequent research, however, would greatly enlarge the role that flight and retreat played in this process. On a long view, it would seem that some, if not most, of the “indigenous” peoples Aguirre Beltrán discusses may actually have once been sedentary cultivators living in highly stratified societies who had been compelled by both Spanish pressure and a massive demographic collapse, owing to epidemics, to reformulate their societies in a way that emphasized adaptation and mobility. Thus Stuart Schwartz and Frank Salomon write of “downward alterations in modular group size, [less] rigidity of kinship arrangements, and [less] socio-political centralization,” which transformed the inhabitants of complex riverine systems into “separately recognized village peoples.” What might later be seen as a backward, even Neolithic, tribal population was more accurately seen as a historical adaptation to political threat and a radically new demographic setting.6

The contemporary understanding, as documented by Schwartz and Salomon, is one of massive population movements and ethnic reshuffling. In Brazil, natives fleeing from the colonial reducciones and the forced labor of the missions—“remnants of defeated villages, mestizos, deserters, and escaped black slaves”—often coalesced at the frontier, sometimes identified by the name of the native peoples among whom they had settled, and sometimes assuming a new identity.7 Like Asian padi states, the Spanish and Portuguese projects of rule required the control of available manpower in state space. The net result of the flight provoked by forced settlement was to create a distinction between state zones on the one hand and state-resisting populations, geographically out of reach and often at higher altitudes, on the other. Allowing for the massive demographic collapse particular to the New World, the resonance with the Southeast Asian pattern is striking. Writing of the 1570 reducción, Schwartz and Salomon claim that the Spanish

forced settlement in nucleated parishes, in the face of population decline and colonial labor needs. This dislocated thousands of Indians and reshuffled people all over the former Inka domains. The project to concentrate dispersed agro-pastoral settlements into uniform European style towns rarely succeeded as planned, but its consequences were somewhat regular if not uniform. They include the enduring antithesis between native outlands and high slopes, and “civilized” parish centers.… Population decline, tightening tribute and the regimen of forced labor quotas drove thousands from home and reshuffled whole populations.8

In the Andes, at least, this sharp contrast between civilized centers and “native outlands” appears to have had a pre-Conquest parallel in the distinction between Inca courts and a state-resisting population at the periphery. The altitudinal dimension, however, was reversed, with the Inca centers at higher altitudes and the periphery being the low, wet, equatorial forests whose inhabitants had long resisted Inca power. This reversal is an important reminder that the key to premodern state-building is the concentration of arable land and manpower, not altitude per se. In Southeast Asia, the larger expanses of arable padi land lie at lower elevations; in Peru, by contrast, there is actually less arable land below twenty-seven hundred meters than above, where the New World staples maize and potatoes, unlike irrigated rice, thrive.9 Despite the reversal of altitudes in the case of Inca civilization, both the Inca and the Spanish states gave rise to a state-resisting, “barbarian” periphery. In the Spanish case, what is most striking and instructive is that much of that barbarian periphery was composed of defectors from more complex, settled societies deliberately placing themselves at a distance from the dangers and oppressions of state space. To do this often meant forsaking their permanent fields, simplifying their social structure, and splitting into smaller, more mobile bands. Ironically, they even succeeded admirably in fooling an earlier generation of ethnographers into believing that scattered peoples such as the Yanomamo, the Siriono, and the Tupo-Guarani were the surviving remnants of ur-primitive populations.

Those populations that had managed to fight free of European control for a time came to represent zones of insubordination. Such shatter zones, particularly if they held abundant subsistence resources, served as magnets, attracting individuals, small groups, and whole communities seeking sanctuary outside the reach of colonial power. Schwartz and Salomon show how the Jívaro and the neighboring Záparo, who had fought off the Europeans and come to control several tributaries of the upper Amazon, became such a magnet.10 The inevitable consequence of the demographic influx gave rise to a characteristic feature of most regions of refuge: a patchwork of identities, ethnicities, and cultural amalgams that are bewilderingly complex.

In North America in the late seventeenth and much of the eighteenth century, the Great Lakes region became a zone of refuge and flux as Britain and France vied for supremacy through their Native American allies, most prominently the Iroquois and Algonquin. The area teemed with runaways and refugees from many areas and backgrounds. Richard White calls this zone “a world made of fragments”: villages of greatly varied backgrounds living side by side and still other settlements of mixed populations thrown together by circumstances.11 In this setting, authority, even at the level of an individual hamlet, was tenuous, and each settlement itself was radically unstable.

The crazy-quilt ethnic array in the New World zones of refuge is further complicated by runaways from a new population imported precisely to counteract the failure to enserf the remaining native population: namely African slaves. As slaves—themselves, of course, a polyglot population—fled servitude, they found themselves in zones of refuge already occupied by native peoples. In places such as Florida, Brazil, Colombia, and many parts of the Caribbean, this encounter gave rise to hybrid populations that defied simple description. Nor were slaves and native peoples the only ones tempted by the promise of life at a distance from the state. Adventurers, traders, bandits, fugitives from the law, and outcasts—the stock figures of many frontiers—also drifted into these spaces and added further to their recondite complexity.

There is something of a rough historical pattern here. State expansion, when it involves forms of forced labor, fosters (geographical conditions permitting) extrastate zones of flight and refuge. The inhabitants of such zones often constitute a composite of runaways and earlier-established peoples. European colonial expansion surely provides the best documented instances of this pattern. But the pattern is equally applicable to early modern Europe itself. The Cossack frontier created by runaways from Russian serfdom from the fifteenth century on is a case in point to which we shall return.

A second instance, that of the “outlaw corridor” in the late seventeenth and early eighteenth century between the agrarian states of Prussia and Brandenburg and the maritime powers of Venice, Genoa, and Marseille, is particularly instructive.12 Competition among the agrarian states for conscripts led to constant sweeps for “vagrants”—virtually anyone without a fixed residence—to fulfill draconian recruitment quotas. Gypsies, the most stigmatized and scourged of the itinerant poor, were criminalized and made the object of the notorious Zegeuner Jagt (Gypsy hunts). To the southwest there was an equally ferocious competition between maritime states for galley slaves, who were also forcibly conscripted from among the itinerant poor. Military or galley servitude, in both zones, was a recognized alternative to the death penalty, and the raids for vagrants correlated closely with the demand for military manpower.

Between these two zones of forced servitude, however, there was a seam of relative immunity to which many of the migrant poor, particularly gypsies, fled. This no-man’s land, this narrow zone of refuge, became known as the “outlaw corridor.” The outlaw corridor was simply a concentration of migrants “between the Palatine and Saxony, which was too far from the Prussian-Brandenburg recruitment area as well as from the Mediterranean (in the latter case, the transportation costs were higher then the price per slave).”13 As in the case of Aguirre Beltrán’s regions of refuge and of maroon communities generally, the outlaw corridor was a state effect and, at the same time, a state-resistant social space forged in conscious response and opposition to subordination.14

Before we turn to Zomia proper, two examples of “hilly” refugees from state control in Southeast Asia merit brief examination. The first—the case of the Tengger highlands in East Java—is one example for which cultural and religious survival appears to loom particularly large in the motives for migration.15 The second case appears to be a nearly limiting case—that of northern Luzon, in which the zone of refuge to which runaways repaired was virtually uninhabited.

The Tengger highlands are distinctive for being the major redoubt on Java of an explicitly non-Islamic, Hindu-Shaivite priesthood, the only such priesthood to have escaped the wave of Islamicization that followed the collapse of the last major Hindu-Buddhist kingdom (Majapahit) in the early sixteenth century. In local accounts, part of the defeated population fled to Bali, while a fraction sought refuge in the highlands. As Robert Hefner notes, “it is a curiosity that the present population of the Tengger highlands should have kept a firm attachment to a Hindu priesthood while utterly lacking Hinduism’s other distinguishing features: castes, courts, and an aristocracy.”16 The highland population was periodically replenished by new waves of migrants seeking refuge from lowland states. As the valley kingdom of Mataram rose in the seventeenth century, it sent repeated expeditions into the hills to capture slaves, driving those who had evaded capture farther up the slopes to relative safety. In the 1670s a Madurese prince revolted against Mataram, now under Dutch protection, and, when the revolt was crushed, the disbanded rebels fled to the hills ahead of their Dutch pursuers. Another rebel and founder of Pasuruan, the ex-slave Surapati, was later routed in turn by the Dutch, but his descendants continued their resistance for years from their redoubts in the Tengger highlands. The case for the Tengger highlands as a product of what Hefner terms 250 years of political violence, as an accumulation of runaways—from slavery, defeat, taxes, cultural assimilation, and forced cultivation under the Dutch—is overwhelming.

By the end of the eighteenth century, much of the population had moved to the highest ground that was least accessible and most defensible, though economically precarious. The history of flight is remembered annually by the non-Islamic highlanders who throw offerings into the volcano in remembrance of their escape from Muslim armies. Their distinct tradition, despite its Hindu content, is culturally encoded in a strong tradition of household autonomy, self-reliance, and an antihierarchical impulse. The contrast with lowland patterns forcibly struck a forestry officer on his first visit: “You couldn’t tell rich from poor. Everyone spoke in the same way, to everyone else too, no matter what their position. Children talked to their parents and even to the village chief using ordinary ngoko. No one bent down and bowed before others.”17 As Hefner observes, the overriding goal of the Tengger uplanders is to avoid “being ordered about”; an aspiration that is deliberately at odds with the elaborate hierarchies and status-coded behavior of the Javanese lowlands. Both the demography and the ethos of the Tengger highlands, then, might fairly be termed a state effect—a geographical place peopled for half a millennium by state-evading refugees from the lowlands whose egalitarian values and Hindu rites are quite self-consciously drawn up in contrast to the rank-conscious, Islamic lowlanders.18

A second historical case from insular Southeast Asia that structurally resembles the case I hope to make for Zomia in general is that of mountainous northern Luzon. Together with the Tengger highlands, northern Luzon can be understood as a smaller-scale Zomia, peopled largely by refugees from lowland subordination.

In his carefully documented Ethnohistory of Northern Luzon, Felix Keesing sets himself the task of accounting for the cultural and ethnic differences between upland and lowland peoples. He rejects accounts that begin from the premise of an essential, primordial difference between the two populations, a premise that would require us to construct separate migration histories to account for their presence on Luzon. Instead, he claims that the differences can be traced to the long Spanish period and to the “ecological and cultural dynamics operating upon an originally common population.”19 The overall picture once again is of flight going back more than five hundred years.

Even before the arrival of the Spanish in the sixteenth century, some of the island population was moving inland out of the range of Islamic slave-traders who raided along the coast. Those remaining near the coast often built watchtowers to provide ample warning in case of approaching slavers. The reasons for evading bondage, however, increased severalfold once the Spanish presence was felt. As in the padi state, the imperative of concentrating population and agricultural production in a confined space was the key to state-making.20 The friar estates, like the Latin American reducciones, were systems of forced labor with a patina of “Christianizing civilization” as their ideological rationale. It was from these “forcing-houses” of lowland power that people fled to the hinterlands and to the hills, which were, Keesing believes, virtually unpopulated until then. The documentary evidence, he claims, “show[s] how the accessible groups faced a choice between submitting to alien control or retreating to the interior. Some retreated into the interior and others subsequently retreated to the mountains in the course of uprisings from time to time against Spanish rule.… Under Spanish rule, retreat into the mountains became a major theme of historical times in all nine of the sectional studies.”21

The uplanders had, for the most part, once been lowlanders whose flight to higher altitudes had begun an elaborate and complex process of differentiation.22 In their new ecological settings, the various groups of refugees adopted new subsistence routines. For the Ifugao, this meant elaborating a sophisticated system of terracing at higher altitudes, allowing them to continue to plant irrigated rice. For most other groups it meant moving from fixed-field agriculture to swiddening and/or foraging. Encountered much later by outsiders, such groups were held to be fundamentally different peoples who had never advanced beyond “primitive” subsistence techniques. But as Keesing warns, it makes no sense to simply assume that a people who are foragers today were, necessarily, foragers a hundred years ago; they might just as easily have been cultivators. The varied timing of the many waves of migration, their location by altitude, and their mode of subsistence account, Keesing believes, for the luxuriant diversity of the mountain ethnoscape in contrast to valley uniformity. He suggests a schematic model for how such ethnic differentiation might have come about: “The simplest theoretical picture … is of an original group, of which part stays in the lowlands and part goes into the mountains. Each then undergoes subsequent ethnic reformulation, so that they become different. Continuing contact, i.e., trade or even war, would affect them mutually. The upland migrating group might split and settle in different ecological settings as, say, at varying elevations, diversifying the mountain opportunities for reformulation.”23 The dichotomy between hill and valley is established by the historical fact of flight from the lowland state by a portion of its population. The cultural, linguistic, and ethnic diversity within the hills is created both by upland conflict and by the great variety of ecological settings and their relative isolation, owing to the friction of terrain, from one another.

Hill and valley lifestyles were, as in most other cases, culturally coded and charged. In Luzon the lowlands were associated with Catholicism, baptism, submission (tax and corvée), and “civilization.” The hills, from the valley perspective, were associated with heathenism, apostasy, primitive wildness and ferocity, and insubordination. Baptism was for a long time seen as a public act of submission to the new rulers and flight a form of insurrection (those who fled were called remontados). There were, as elsewhere, distinctions made in the valley centers between “wild” (feroces) hill people and “tame” (dociles), rather like the U.S. cavalry distinguished between “friendlies” and “hostile redskins.” In Luzon what was a common population riven by a basically political choice between becoming a subject of a more hierarchical valley polity or electing a relatively autonomous life in the hills was reconfigured as an essential and primordial difference between a civilized and advanced population on the one hand and a primitive, backward people on the other.

The term savages, used by so many authors to denote all the hill tribes of Indo-China, is very inaccurate and misleading, as many of these tribes are more civilized and humane than the tax-ridden inhabitants of the plain country, and indeed merely the remains of once mighty empires.

—Archibald Ross Colquhoun, Amongst the Shans, 1885

The peopling of Zomia has largely been a state effect. The nearly two millennia–deep movement of peoples from the Yangzi and Pearl river basins and from Sichuan and the Tibetan plateau defies a simple accounting, even in hands far more competent than my own. Theories and legends abound, but verifiable facts are scarce, not least because the “peoples” in question were designated by so many different and incompatible labels that one can rarely be sure just whom is being specified. There is no reason to assume, for example, that a group designated as Miao—in any case an exonym—in the fifteenth century bears any necessary relation to a group labeled Miao by a Han administrator in the eighteenth century. Nor is the confusion confined to the terminology. In the jumble of repeated migrations and cultural colli sions, group after group was reshuffled and transformed so frequently that there is no reason whatever to assume any long-run genealogical or linguistic continuity to such peoples.

In the face of this truly radical uncertainty about identities, it is possible to hazard some broad generalizations about the general pattern of movement.

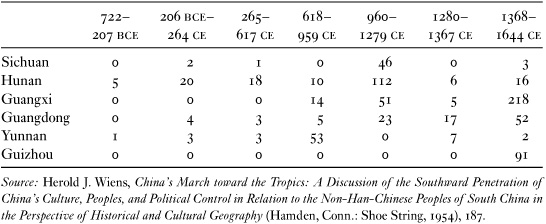

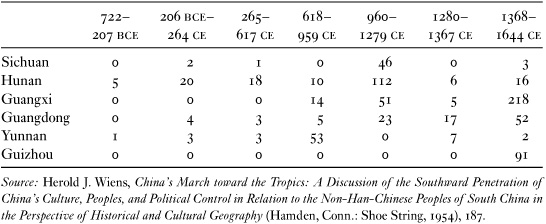

Table 2 Uprisings in Southwest China by Province, as recorded in the Great Chinese Encyclopedia to the Mid-Seventeenth Century

As the Han kingdoms expanded beyond their original, nonpadi heartland in the Yellow River area, they expanded into new padi state zones—that is, the Yangzi and Pearl river basins and westward along river courses and flatlands. The populations living in these zones of expansion had three choices: assimilation and absorption, rebellion, or flight (often after failed resistance). The shifting tempo of revolt by province and dynasty provides a rough geographical and historical gauge of Han state expansion. Revolts typically occurred in those zones where Han expansionary pressure was most acute. A table of uprisings sufficiently large to make it into the Great Chinese Encyclopedia is suggestive.

Table 2 reflects the major thrust in the early Tang Dynasty into Yunnan and the subsequent Song efforts to control Sichuan, Guangxi, and Hunan. A comparative lull, in this region at least, was followed in the late fourteenth century by a massive Ming invasion of some three hundred thousand troops and military colonists designed to rout the Yuan holdouts. Many of the invaders stayed on as settlers like the Yuan before them, and this provoked numerous uprisings, especially among the Miao and Yao in Guangxi and Guizhou.24 Imperial aggression and armed resistance in these same areas, though not shown in the table, continued under the Manchu/Qing, whose policy of shifting from tributary rule to direct Han administration provoked further unrest and flight. Between 1700 and 1850 some three million Han settlers and soldiers entered the southwest provinces, swelling the Han proportion of the twenty million inhabitants of this zone to 60 percent.25

At each stage of the Han expansion, a fraction, large or small, came under Han administration and was eventually absorbed as taxpaying subjects of the kingdom. Though such groups left their mark, often indelible, on what it meant to be a “Han” in that area, that fraction disappeared as a named, self-identified ethnic group.26 Wherever there were open lands to which those preferring to remain outside the Han state could flee, however, emigration remained an ever-present possibility. Those groups accustomed to irrigated-padi agriculture, most notably the Tai/Lao, sought out the small upland valleys where wet-rice cultivation was easiest. Other groups retreated to the more remote slopes and ravines regarded by the Han as fiscally sterile and agriculturally unpromising, where they had a sporting chance of remaining independent. This process is the dominant process by which, over centuries, it seems, the hills of Zomia were populated. As Herold Wiens, the pioneer chronicler of these vast migrations, summarizes at length,

The effect of these invasions was the settlement of southern China by Han-Chinese in progressive stages from the Yangtzu River valley southwestward to the Yunnan frontiers, and the shifting of the tribal peoples of south China from their old stamping grounds, forcing them from the better agricultural lands. The movement of the tribes people determined to preserve their way of life were toward the sparsely settled frontier lands where the more unfavorable environment promised to deter the rapid advance of the Han-Chinese—i.e. the humid, hot, malarial regions. A second direction of movement was the vertical movement into the more unfavorable environments of the high mountain lands mostly unsuitable for rice-cultivation and undesired by the Han-Chinese agriculturalists. In the first direction moved the valley-dwelling, rice-raising, water-loving Tai tribes people. In the second direction moved the mountain-roving, fire-field or shifting agriculturalists, the Miao, the Yao, the Lolo and their related agricultural groups. Nevertheless, the vertical movements did not find sufficient room for the displaced mountain tribesmen, so that among them, also, there have been migrations to the south and southwest frontier regions and even across the frontiers into Vietnam-Laos and northern Thailand and northern Burma.27

The great hilly barrier to the expansion of Han state power and settlement, where the friction of distance that impedes movement is at its greatest, is in the uplands of Yunnan, Guizhou, and northern and western Guangxi. Since this rugged topography continues southward, across what have become international boundaries, into the northern sections of the mainland Southeast Asian states and northeastern India, these areas too must be considered a part of what we are calling Zomia. It is to precisely this geographical bastion against state expansion that the populations seeking to evade incorporation have been driven. Having, over time, adapted to a hilly environment and, as we shall see, developed a social structure and subsistence routines to avoid incorporation, they are now seen by their lowland neighbors as impoverished, backward, tribal populations that lacked the talent for civilization. But, as Wiens explains, “There is no doubt that the early predecessors of the present day ‘hill-tribes’ occupied lowland plains as well.… It was not until much later that there developed a strict differentiation of the Miao and Yao as hill-dwellers. This development was not so much a matter of preference as of necessity for those tribesmen wishing to escape domination or annihilation.”28

Any attempt to craft a historically deep and accurate narrative of migration for any particular people is fraught with difficulty, in part because the groups have been reformulated so often. Wiens has, nevertheless, tried to piece together a sketchy history for the large group known, to the Han, as the Miao, a portion of whom call themselves Hmong. It appears that around the sixth century, the “Miao-Man” (“barbarians”), with their own gentry, were a major military threat to Han valleys north of the Yangzi—fomenting more than forty rebellions between 403 and 610. At a certain point they were broken up and those not absorbed were then thought to have become a dispersed, ununified people without a nobility. The term Miao came over time to apply rather indiscriminately to almost any acephalous people on the frontier of the Han state—virtually shorthand for “barbarian.” For the past five hundred years, under the Ming and Qing, campaigns for assimilation or “suppression and extermination” were nearly constant. Suppression campaigns following insurrections in 1698, 1732, and 1794, and above all the rising in Guizhou in 1855 dispersed the Miao in many different directions throughout southwest China and mountainous mainland Southeast Asia. Wiens describes these campaigns as ones of expulsion and extermination comparable to “the American treatment of the Indians.”29

One result of the Miao’s headlong flight was their wide dispersal throughout Zomia. Although generally at higher altitudes growing opium and maize, the Miao/Hmong can be found planting wet rice, foraging, and swiddening at intermediate altitudes. Wiens explains this diversity by the timing of the Hmong appearance in a particular locality and their relative strength vis-à-vis competing groups.30 Latecomers, if they are militarily superior, will typically seize the valley lands and force existing groups to move upward, often in a ratcheting effect.31 If the latecomers are less powerful, they must occupy whatever niches are left, often higher up the slopes. Either way, there is a vertical stacking of “ethnicities” on each mountain or range of mountains. Thus in southwest Yunnan there are some Mon below fifteen hundred meters, Tai in upland basins up to seventeen hundred meters, Miao and Yao at even higher elevations, and finally the Akha, presumably the weakest group in this setting, who are near the crest of the mountains, up to eighteen hundred meters.

Of the cultures and peoples pushed west and southwest into the hills of Zomia, the Tai were apparently the most numerous and, today, the most prominent. The greater Tai linguistic community includes the Thai and lowland Lao, the Shan of Burma, the Zhuang of southwestern China (the largest minority in the People’s Republic), and various related groups from northern Vietnam all the way to Assam. What distinguished many (but not all) of the Tai from most other Zomia peoples is that, by all accounts, they seem always to have been a state-making people. That is, they have long practiced wet-rice cultivation, they carry the social structure of autocratic rule, military prowess, and, in many cases, a world religion that facilitates state formation. “Tainess” historically may in fact more accurately be seen like “Malayness”: that is, as a state-making technology borne by a thin superstratum of military elites/aristocrats into which many different peoples have, over time, been assimilated. Their greatest state-making endeavor was the kingdom of Nan Chao and its successor Dali, in Yunnan (737–1153), which fought off Tang invasions and, for a time, managed to seize Sichuan’s capital, Cheng-du.32 Before being destroyed by the Mongol invasion, this center of power had conquered the Pyu kingdom in central Burma and expended its reach into northern Thailand and Laos. The Mongol victory led to a further dispersal throughout much of highland Southeast Asia and beyond. In the hills, wherever there was a suitable rice plain, one was likely to find a small state on the Tai model. Apart from favorable settings like Chiang Mai and Kengtung, most such states were small affairs in keeping with their confined ecological limits. They were, in general, in competition with one another for population and trade routes, such that one British observer could aptly describe the hills of eastern Burma as “a bedlam of snarling Shan states.”33

The complexities of migration, ethnic reformulation, and subsistence patterns in Zomia, or any shatter zone of long duration, are daunting. Although a group may have moved initially to the hills to escape, say, the pressure of the Han or Burmese state, innumerable subsequent moves and fragmentations might have any number of causes—for example, competition with other hill peoples, shortage of land for swiddens, intragroup friction, a run of bad luck indicating that the spirits of the place were ill-disposed, evading raids, and so forth. Any large migration, moreover, set off a chain reaction of subsidiary moves impelled by the first—rather like the sequence of invasions of steppe peoples, themselves often set in motion by others, that brought the Roman Empire to its knees or, to use a more contemporary simile, like a maniacal game of fairground bumper-cars, each adding its shock wave to the previous impacts.34

Many also of the Burmans and Peguans, unable any longer to bear the heavy oppressions and continual levies of men and money made upon them, have withdrawn themselves from their native soil, with all their families … and thus not merely the armies but likewise the very population of this kingdom has been of late much diminished.… When I first arrived in Pegu, each bend of the great river Ava [Irrawaddy] presented a long continual line of habitations, but on my return, a very few villages were to be seen along the whole course of the stream.

—Father Sangermano, c. 1800

The nearly two-millennia push—sporadic but inexorable—of the Han state and Han settlers into Zomia has surely been the single great historical process most responsible for driving people into the hills. It has not by any means, however, been the only dynamic. The waxing of other state cores, among them Pyu, Pegu, Nan Chao, Chiang Mai, and various Burmese and Thai states have themselves set people in motion and driven many of them out of range. “Ordinary” state processes, such as taxation, forced labor, warfare and revolt, religious dissent, and the ecological consequences of state building have been responsible for both a routine extrusion of beleaguered subjects and, more historically notable, moments when circumstances provoked large-scale, headlong flight.

It would be difficult to exaggerate the degree to which the cultivators of Southeast Asia—in the plains or in the hills—were footloose. Early European visitors, colonial officials, and historians of the region note the exceptional proclivity of villagers to migrate whenever they were dissatisfied with conditions or perceived opportunities in a new direction. The Gazetteer of Upper Burma and the Shan States, which contains a brief account of literally thousands of villages and towns, bears this out.35 Again and again, the compilers are told that the village was founded recently or several generations back by people who had come from elsewhere, usually to escape war or oppression.36 In other cases, settlements that were previously quite prosperous towns are either completely deserted or reduced to small hamlets of remnants. All the evidence suggests that precolonial displacement and migration was the rule rather than the exception. The startling and generalized physical mobility of Southeast Asian cultivators—including those growing irrigated rice—was completely at odds with “the enduring stereotype of the territorially rooted, peasant household.” And yet, as Robert Elson explains, “mobility rather than permanency seems to have been a keynote of peasant life in this [colonial] era as well as previous ones.”37

Much of this migration was undoubtedly a lowland affair—between one lowland kingdom and another, from the core of a kingdom to its periphery, from resource-poor areas to resource-rich ones.38 But a good deal of this movement, as we have already seen, was movement to the hills, to higher elevations, and thus to areas more likely to be beyond the reach of a lowland state. Responding to Burmese conscription and taxes during an early-nineteenth-century Burmese invasion of Assam, the population of Möng Hkawn, a valley town in the upper Chindwin, fled to higher ground; “to avoid the oppression to which they were constantly exposed, the Shans sought an asylum in the remote glens and valleys on the banks of the Chindwin, and the Kachins among the recesses of the mountains at the eastern extremity of the valley.”39 Elaborating on this pattern, J. G. Scott wrote that the “hill-tribes” were relegated to the hills and to what he saw, mistakenly, as a far more onerous form of agriculture by virtue of defeat. “This hard work is left to mild aboriginal or other tribes, whom the Burman has long ago bullied out of the fat lowlands.”40 Elsewhere, contemplating the ethnic diversity of the hills, Scott hazarded a synoptic view of the whole of Zomia as a vast zone of refuge or “shatter zone.” His formulation, echoing as it does that of Wiens noted earlier, merits quotation at length:

Indo-China [Southeast Asia] seems to have been the common asylum for fugitive tribes from both India and China. The expansion of the Chinese Empire, which for centuries did not extend south of the Yang-tzu River, and the inroads of the Scythian tribes on the empires of Chandra-gupta and Asoka combined to turn out the aborigines both to the northeast and northwest and these met and struggled for existence in Indo-China. It is only some such theory that will account for the extraordinary variety and marked dissimilarity of races found in the sheltered valleys and the high ranges of the Shan States and the surrounding countries.41

Scott’s view of Zomia as a region of asylum is, I believe, substantially correct. What is misleading, however, is the implicit assumption that the hill peoples the colonizers encountered were all originally “aboriginal” peoples and that their subsequent histories were those of coherent, genealogically and linguistically continuous communities. Many of the people in the hills were, in all likelihood, valley peoples who long ago had fled state space. Others, however, were “state-making” valley peoples, like many of the Tai, who lost to more powerful states and who scattered or moved together to the hills. Still others, as we shall see, were the shards of valley states: deserting conscripts, rebels, defeated armies, ruined peasants, villagers fleeing epidemics and famine, escaped serfs and slaves, royal pretenders and their entourages, and religious dissidents. It is these peoples disgorged by valley states, together with the constant mixing and reconstitution of hill peoples in their migrations, that make identities in Zomia such a legitimately bewildering puzzle.42

Just how decisive flight over the centuries was demographically for the peopling of the hills is difficult to judge. To gauge that would require more data than we have about hill populations a millennium or more ago. What sparse archeological evidence we do have, however, suggests that the hills were thinly populated. Paul Wheatley claimed that in insular Southeast Asia—perhaps like Keesing’s mountainous Northern Luzon—the mountains were essentially unoccupied until very recently, making them “of no human significance prior to the late 19th century.”43

The reasons why subjects of valley states might wish to, or be forced to, move away, defy easy accounting. What follows is a description of some of the most common causes. It ignores one common historical event that, as it were, placed people beyond the reach of the state without actually moving: the contraction or collapse of state power at its core.44

The key to statecraft in precolonial Southeast Asia, one honored as often in the breach as in its observance, was to press the kingdom’s subjects only so far so as not to provoke their wholesale departure. In areas where relatively weak kingdoms competed for manpower, the population was not, generally, hard-pressed. Indeed, under such circumstances settlers might be enticed by grain, plow animals, and implements to settle in underpopulated districts of a kingdom.

A large state lording it over a substantial wet-rice core was, as a monopolist, more inclined to press its advantage to the limit. This was especially so at the core and when the kingdom faced attack or was itself ruled by a monarch with grandiose plans of aggression or pagoda-building. Inhabiting the classical agricultural core of all precolonial Burmese kingdoms, the population of Kyauk-se was ruinously poor because of overtaxation.45 The risk of overexploitation was aggravated by several features of precolonial governance: the use of “tax farmers,” who had bid for the right to collect taxes and were determined to turn a profit, the fact that something close to half the population were captives or their descendants, and the difficulty of estimating the all-important harvest yield for any particular year, and, hence, what the traffic would bear. Corvée labor and taxes on households and land were, moreover, not the end of it. Taxes and fees were levied, in principle at least, on every conceivable activity: livestock, nat worship shrines, marriages, timber, fish traps, caulking pitch, saltpeter, beeswax, coconut and betel trees, and elephants, as well, of course, as innumerable tolls on markets and roads. Here it is useful to recall that the working definition of being a subject of a kingdom was not so much ethnic as the civil condition of being liable to tax and corvée.46

Pushed to the breaking point, the subject had several choices. The most common, perhaps, was to evade crown service, the most onerous becoming a “subject” of an individual notable or of a religious authority, all of whom competed for manpower. Failing that, movement to another adjacent lowland kingdom was an option. In the past three centuries, many thousands of Mon, Burman, and Karen have moved into the Thai orbit in just this fashion. Another option was to move outside the state’s reach altogether—to the hinterland and/or the hills. All these options were generally preferred to the risks of open rebellion, an option confined largely to elites contending for the throne. As late as 1921 the response of the Mien and Hmong to intense pressure for corvée labor from the Thai state was to disappear into the forest, after which they fade from official notice. This was, presumably, precisely what they had intended.47 Oscar Salemink reports even more contemporary instances of hill peoples moving in groups to more remote areas, often at higher elevations, to escape the impositions of Vietnamese officials and cadres.48

The loss of population, as noted, operated as something like a homeostatic device, sapping the power of a kingdom. It was often the first tangible sign that certain limits of endurance had been breached. A proximate sign, much noted in the chronicles, was the appearance of a “floating” population either begging or resorting to theft and banditry in their desperation. The only sure way to evade the burdens of being a subject in bad times was to move away. Such a move quite often meant moving from wet-rice agriculture to swiddening and or foraging. How common this was is impossible to tell for sure, but to judge by the number of oral histories in which hill people recount a past as padi growers in the lowlands, it is not negligible.49

We are like ants, traveling away from our trouble to a safe place. We left everything behind to be safe.

—Mon villager fleeing to Thailand, 1995

Constant rebellions and wars between the Peguans and Burmese and Shans … afflicted the country for 500 years. All those who were not killed were driven away from their former homes by ruthless invaders or were drafted off to fight for the king.… Thus in some cases the proprietors [cultivators] were killed out, in others they left for districts so remote that it was impossible to retain a hold on the ancestral property, however great their attachment to it.

—J. G. Scott [Shway Yoe], The Burman

The expression “states make wars and wars make states,” coined by Charles Tilly, is no less true for Southeast Asia as it was for early modern Europe.50 For our purposes, the corollary of Tilly’s adage might be: “States make wars and wars—massively—make migrants.” Southeast Asia wars in the same period were at least as disruptive. Military campaigns mobilized more of the adult population than their European counterparts, and they were at least as likely to spawn epidemics (cholera and typhus, in particular), famine, and the devastation and depopulation of the defeated kingdom. The demographic impact of the two successful Burmese invasions of Siam (1549–69 and the 1760s) was enormous. The core population around the defeated capital vanished; a small fraction was captured and returned to the Burmese core, and most of the rest dispersed to areas of greater safety. By 1920 the population of the Siamese core region had only just recovered to its preinvasion level.51 The hardships even a successful war was likely to inflict on the staging area of the campaign were often no less devastating than those inflicted on the enemy. Having sacked the Siamese capital, Burmese King Bayin-naung’s mobilization had exhausted the food and population surpluses of the delta area around Pegu. After his death in 1581, subsequent wars between Arakan, Ayutthaya, and the Burmese court at Taung-ngu turned the territory near Pegu into a “depopulated desert.”52

Warfare for civilian noncombatants, especially those on the route of march, was, if anything, more devastating than for conscripts. If a late-seventeenth-century European army of sixty thousand troops required forty thousand horses, more than one hundred carts of provisions, and almost a million pounds of food per day, one can appreciate the wide swath of pillage and ruin a Southeast Asian army left in its wake.53 For this reason the invasion routes were seldom the most direct, as-the-crow-flies trajectory but rather traced routes calculated and timed to maximize the manpower, grain, carts, draft animals, and forage—not to mention the private looting—that a large army required. A simple calculation can help convey the extent of the devastation. If we assume, as John A. Lynn does, that an army forages 8 kilometers on either side of its line of march and marches 16 kilometers a day, it would then scour 260 square kilometers of countryside for each day of the campaign. A ten-day march by the same army might then affect 26 thousand square kilometers.54 The major threat from incessant wars was, in manpower-starved kingdoms, not so much that of being killed; a lucky combatant in this form of military “booty-capitalism” might actually aspire to capture people himself and sell them as slaves for a profit. The danger, rather, was the utter devastation visited on those who lay athwart the line of march—the danger of being captured or else having to flee and abandon everything to the army. It mattered little whether the army in question was “one’s own” or that of a neighboring kingdom, the quartermaster’s requirements were the same, and so, largely, was the treatment of civilians and property. A striking example comes from the Burmese-Manipur War(s), which continued sporadically from the sixteenth century into the eighteenth. The repeated devastation drove the Chin-Mizo plains-dwellers from the Kabe-Kabaw Valley up into the hills, where, subsequently, they became known as a “hill people”—presumably “always there.”

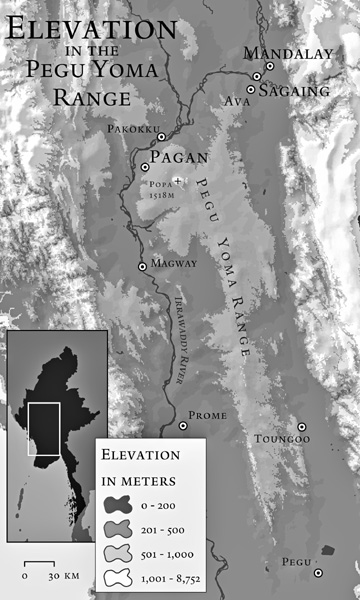

The late-eighteenth-century mobilizations of Burmese King Bò-daw-hpaya (r. 1782–1819) in the service of his extravagant dreams of conquest and ceremonial building were ruinous to the kingdom as a whole. First, a failed invasion of Siam in 1785–86 in which half the army of perhaps three hundred thousand disappeared, then a massive labor requisition to build what would have been the largest pagoda in the world, followed by mobilizations to repel the Thai counterthrust and to extend the Meiktila irrigation system, and, finally, another general mobilization for a last, and disastrous, invasion of Thailand from Tavoy sent the population of the kingdom reeling. An English observer noted that the population of lower Burma was fleeing “to other countries” in fear of conscription and the predations of armies. Banditry and rebellion were widespread, but the typical response was to flee to areas farther from the state core and from the king’s own marauding army. Rumors of its approach would send subjects across the horizon in dread and mortal fear, for their own troops “bore every appearance of the march of a hostile army.”55 And for every major war there were probably scores of smaller campaigns between petty kingdoms, or, for that matter, civil wars between claimants to the throne, like the one in 1886 in Hsum-Hsai, a petty principality in the modest Shan kingdom of Hsi-paw, that left the district largely deserted. The prolonged civil war in the late nineteenth century for control of another Shan state, Hsen-wi, was so devastating that finally “the greatest of the modern Shan capitals would hardly form a bazaar suburb to one of the older walled cities.”56

The first aim of a civilian was to avoid conscription. In a time of mobilization, conscription quotas were set for every district. Sure indications of evasion were the frequent successions of increasingly draconian quotas (for example, first, one of every two hundred households, then one of fifty, then one of ten, and finally a general mobilization). The quotas were rarely reached, and tattooing was used to mark recruits so that they could be identified later. It was also possible in the late Kon-baung period, and probably earlier as well, for those of some means to bribe their way out of conscription. But the surest way of avoiding the military draft was to move out of the padi state core and away from the army’s route of march. It was the misfortune of the Sgaw and especially the Pwo Karen to inhabit the invasion (and retreat!) routes in the Burmo-Siamese wars of the late eighteenth century. Ronald Renard claims that it was precisely in this period that they dispersed to the mountains along the Salween River and took to living in more easily defended longhouses along the ridges. Even those who much later placed themselves under Thai protection refused to establish permanent settlements since they “still preferred the wandering, swiddening life which, they claimed, freed them from the vulnerability of being attached to specific lands.”57

Once an army was conscripted, heroic efforts were necessary to hold it together throughout an arduous campaign. A late-sixteenth-century European voyager noted the pillaging and burning characteristic of Burmese-Siamese warfare and then added, “but in the end they never return home without leaving half of their people.”58 Since we know that such wars were not particularly sanguinary, it is most likely that the bulk of the losses were to desertion. Evidence from the Glass Palace Chronicle account of a failed Burmese siege confirms this suspicion. After a five-month siege, the attackers were short of provisions and an epidemic broke out. The army, which began with 250,000 troops, according to the chronicle, disintegrated totally, and after a disastrous retreat, “the King reached his capital with a small escort.”59 The vast majority, one imagines, deserted once the siege faltered and the epidemic began, making their way back or beginning new lives in a safer place. In a late-nineteenth-century Burmese military expedition against the Shan, J. G. Scott reported, the minister in charge of the troops “effected nothing warlike, and rumor said he was so fully occupied keeping the troops from dispersing, that he had no time to fight.”60 We know that rates of desertion, as in virtually all premodern armies, were high, especially in a failed campaign.61 How many of the deserters—or displaced civilians, for that matter—ended up in the hills and other faraway places is impossible to judge. But the fact that many of the troops were either “press-ganged” or slaves and their descendants and that, owing to the warfare itself, many of them had nothing to return to suggests that many of the deserters began new lives elsewhere.62

There are some shards of evidence that the dangers and displacement of warfare pushed many onetime padi cultivators to the hinterlands and to higher elevations, and hence to new subsistence routines. The Ganan, for example, are today an apparently minority people, some eight thousand strong, living in the headwaters of the Mu River (Sagaing Division, Burma) among three thousand–foot peaks cleaved by deep ravines.63 They were, or had become, it seems, a lowland people and an integral part of the Pyu padi state until its centers were sacked and destroyed by Mon, Burman, and Nan Chao forces between the ninth and fourteenth centuries. They fled up the Mu River watershed because it was “away from the battlefields”; there they became, and remain, swiddeners and foragers. They have no written language, and they practice a heterodox variant of Buddhism. Their account accords, as we shall see, with that of many contemporary hill people who claim a lowland past.

Here and there, one encounters more contemporary evidence of flight to the hills to evade capture or the predations of warfare. J. G. Scott believed that the present hill groups around Kengtung/Chaing-tung, in Burma east of the Salween, were once settled on the plain around Kengtung and were driven by Thai invasions into the hills where they now swidden.64 And Charles Keyes cites a nineteenth-century missionary account of an isolated Karen group which had fled the Siamese to a nearly inaccessible mountain gorge between Saraburi and Khorat from a previously more lowland setting.65 The northern Chin, for their part, fled to more remote hills to escape Shan-Burmese warfare in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, occasionally providing refuge in turn to rebel Burmese princes fleeing the king’s troops.66

In the context of warfare, it is important to note that the devastation of a state’s padi core has the effect of nullifying state space in terms of both political power and ecology. Even allowing for hyperbole, the following description of Chiang Mai after the Burmese invasion is instructive: “Cities became jungles, rice fields became grasslands, land for elephants, forests for tigers, where it was impossible to build a country.”67 It would be tempting to believe that plainsmen, now free of their burdens as state subjects, could remain in place. The problem, however, was that the defeat of a kingdom provoked a competitive scouring of the remnant population by neighboring states and slave-raiders. Shifting from the plains to a location far less accessible to armies and slavers offered a reasonable chance of autonomy and independence. This is exactly the option, Leo Alting von Geusau claims, that was taken by the Akha and many other groups today viewed as hill people “from time immemorial”:

Over many centuries, therefore, the more inaccessible parts of mountainous Yunnan and neighboring Vietnam, Laos, and Burma became the zones of refuge for tribal groups marginalized by the smaller vassal states which occupied the lower land areas. In this process of marginalization, tribal groups such as the Hani and Akha also selected and constructed their habitats—in terms of altitude and surrounding forestation—in such a way that they would not easily be accessible to soldiers, bandits, and tax collectors. Such processes have been termed “encapsulation.”68

Raiding is our agriculture.

—Berber saying

Concentrated population and grain production was, as we have seen, normally a necessary condition for state formation. Precisely because such areas offered a potential surplus for state-building rulers, so also did they represent an irresistible target for raiders. For all but the largest court centers, the threat of raids by slavers and/or bandits was a real and present danger. Fear of Malay slave raiders in the early colonial period had depopulated many of the coastal areas of Burma and Siam; the Karen on this account avoided roads and exposed beaches. Prolonged vulnerability was likely to be turned into a system of subordination and predation. A situation of this kind prevailed in the upper Chindwin Kubo Valley, where the hill-dwelling Chins had made themselves masters of the valley Shans, carrying many of them off as slaves.69 A substantial town of five hundred households and thirty-seven monasteries in 1960 was reduced, in this way, to only twenty-eight houses.

It was generally in the interest of hill people, where they did dominate the adjacent valley, to defend valley settlements with which they could trade and from which they could extract a regular tribute. Under stable conditions, a kind of protection racket–cum–blackmail relationship developed. On occasion, hill groups such as the Kachin found it in their interest actually to establish settlements “in the plains or on the rivers at the foot of the hills.” Much as the Berbers talked about tribute from sedentary communities as “our farming,” so, in the Bhamo area along the upper Irrawaddy, did the Kachin appoint Burmese and Shan headmen. “It appears that there was hardly a village in the whole Bhamo district which was thus not protected and the Kachins were really masters of the country.”70 At its most placid and routinized, this arrangement comes close to resembling the successful premodern state: namely, a monopolistic protection racket that keeps the peace and fosters production and trade while extracting no more rents than the traffic will bear.

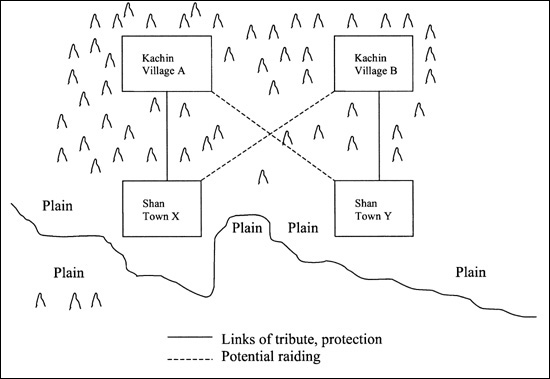

And yet again and again, hill people in such zones raided valley settlements to the point where they “killed the goose that laid the golden egg,” leaving a devastated and uninhabited plain.71 Why? The answer, I believe, is to be found in the political structure of the hills, characterized by many small competing polities. Each of these hill polities might have “associated” valley settlements that they were protecting. In the simplest, most schematic terms, it would look roughly like figure 2.

Because Kachin group A might live three or four days from a village it protected, Kachin group B might be able to raid the village protected by A and get away. When the raid became known, Kachin group A might then retaliate by raiding another lowland settlement protected by offending group B. This might, of course, spark a highland feud unless some accommodation was reached.72

There are several consequences of this pattern that bear on the general argument I am making. The first is that what looks, especially to valley peoples(!), as generalized raiding by hill “tribes” is, in fact, a fairly finely articulated expression of hill politics. Second, if this pattern is widespread, it leads to the depopulation of large areas and a withdrawal of vulnerable lowlanders to, in this case, places farther from the hills and nearer the river where flight was easiest. Finally, and perhaps most important, the primary objective of these raids was the taking of slaves, many of whom would be kept by the Kachin or sold to other hill peoples or slave-traders. To the degree that such raiding was successful, it represented a net demographic transfer of population to the hills. It was yet another process by which valley people became hill people and by which the hills were made more cosmopolitan culturally.

2. Schema of hill-valley raiding and tribute relations

Certain hill peoples became known, and even notorious, as slave-raiders. In the Shan states generally, the Karenni (Red Karen) were particularly feared. Postharvest raiding for slaves became, in certain areas, routine.73 “Thus, in most of the Karenni villages are to be found Shan-yangs of the Karen tribes, Yondalines, Padaungs, and Let-htas of the mountain ranges to the northwest, all doomed to a hopeless state of slavery…. They are sold to the Yons (Chiang Mai Shan) by whom they are resold to the Siamese.”74 The list of Karenni captives is indicative, for it contains the names of hill peoples as well as valley populations. Slave-raiding peoples like the Karenni, specializing in the most valuable trade good, people, not only abducted valley dwellers to incorporate them into hill society or to resell them in valley markets; they also abducted vulnerable hill people and enslaved them or resold them. They were, in a sense, a reversible conveyor belt of manpower, now supplying the raw material for state-making in the valley, now looting vulnerable valley settlements for their own manpower needs. In any event, the pattern helps explain why plainsmen were wary of raiders and why weaker hill peoples retreated to inaccessible locations, often in fortified and concealed ridgetop stockades, to minimize their exposure.75

Rebellions and civil wars in the lowlands hold many of the same terrors for villagers as do wars of conquest or invasions. They provoke similar patterns of flight as people frantically move to locations where they imagine they will be safer. What is notable, however, is that these repertoires of flight have logic to them, and that logic depends heavily on class, or, more precisely, on the degree to which one’s status, property, and life are guaranteed by the routines of state power. The logic is evident even in the fracture lines of flight during the early years of the Vietnam War in the south from 1954 to 1965. Landlords, elites, and officials, fearing for their safety, increasingly gravitated away from the countryside and toward provincial capitals and eventually, as the conflict escalated, to Saigon itself. The closer to the state core, their movements seemed to say, the safer they were. Many ordinary peasants, by contrast, shifted from a more sedentary life in large villages to more remote, mobile settlements outside the state’s easy reach. It is as if the tenuous, social compact of state-based society had come undone: elites heading for the center, where the coercive power of the state was most felt, and vulnerable nonelites heading for the periphery, where the coercive power of the state was least felt.

Rebels, of course, unless they are very powerful, have even more compelling reasons to head for the hills. The earlier stages of the war in Indochina (1946–54) caused, as Hardy explains, “the movement of large numbers of Viêt people from the Red River Delta into the remotest parts of the northern highlands. Forests provided cover for the revolution all the way to the valley of Dien Bien Phu, near the border with Laos.”76 The pattern is historically deep in Vietnam and elsewhere. It can be traced, at least, to the massive Tay Son rebellion (1771–1802), which began when three brothers from Tay Son village fled to the nearby hills for safety and to recruit followers. It continued through the Can Vuong movement in early colonial Vietnam, to the Nghe-Tinh uprisings of 1930, and, finally, to the Vietminh base area in the hills among the minority Tho people.77 State evasion by threatened rebels and noncombatants alike often entails migration to new ecological settings and the adoption of novel subsistence routines. Such routines are not only more suited to the new location but are also typically more diverse and mobile, thus making their practitioners less legible to the state.

Defeated rebellions, like war in general, drove the vanquished to the margins. The larger the rebellion, the greater the population displaced. In this respect, the second half of the nineteenth century in China was a time of enormous upheavals, which put hundreds of thousands to rout, many of whom then sought refuge farther away from Han power. The greatest of these upheavals resulted from the Taiping Rebellion from 1851 to 1864, certainly the largest peasant rebellion in world history. The second upheavals, in Guizhou and Yunnan, sometimes called the Panthay Rebellion, were massive uprisings lasting from 1854 to 1873 and involving “renegade” Han and Miao/Hmong hill people, as well as Hui-Chinese Muslims. Although the so-called Miao Rebellion never reached the amplitude of the Taiping rising—which cost the lives of some twenty million people—it nevertheless persisted for nearly two decades before its suppression. Defeated rebels, their families, and whole communities in headlong flight retreated into Zomia in the case of the Taiping Rebellion and, in the case of the Miao Rebellion, deeper and farther south within Zomia. In flight from Han power, these migrations not only led to widespread looting, banditry, and destruction but they also further complicated the already diverse ethnoscape of the hills. In a ratchet effect, fleeing groups often drove others before them. Thongchai Winichakul claims that many of the Chinese entering northern Siam in the late nineteenth century were remnants of the Taiping forces.78 The defeated remnants of the Miao Rebellion pushed south and many Lahu and Akha groups, not involved in the rebellion itself, moved south with them or ahead of them to stay out of harm’s way.79 In the twentieth century, a successful rebellion—the Communist Revolution in China—produced a new stream of migrants: defeated Republican-Kuomintang troops. Settling in the area that is today known as the Golden Triangle, where Laos, Burma, China, and Thailand (nearly) meet, they have with their hill allies come to control much of the opium trade. Thanks to the friction of terrain that their remote location in the hills affords, they also take political advantage of being situated along the seam of four nearly contiguous national jurisdictions.80 They are hardly the most recent migrants into Zomia’s region of refuge. In 1958, under pressure from Chinese party cadres and soldiers, fully one third of the Wa population crossed the border from the People’s Republic into Burma seeking refuge.81 During the Cultural Revolution, another pulse of migration followed.

The retreat of Kuomintang forces to the Golden Triangle serves to remind us that the hills and Zomia in particular have long been a destination of retreat (and renewed military preparations) for officials of a defeated dynasty, princely pretenders, and losing factions in court politics. Thus at the beginning of the Manchu Dynasty, fleeing Ming princes and their entourages retreated to safety in Guizhou and beyond. In Burma the Shan and Chin Hills were host in precolonial and early colonial times to princely rebels and fugitive claimants to the throne of Burma (mín laún).

Political dissent and religious heresy or apostasy are, especially before the nineteenth century, difficult to distinguish from each other, so frequently are they alloyed. Nevertheless, it merits emphasis that the hills are associated as much with religious heterodoxy vis-à-vis the lowlands as they are with rebellion and political dissent.82 That this should be the case is not surprising. Given the influence of the clergy (sangha) in Theravada countries like Burma and Siam and a cosmology that potentially made the ruler into a Hindu-Buddhist god-king, it was at least as vital for the crown to control the abbots of the realm as it was to control its princes—and at least as difficult. The crown’s ability to impose its religious writ at a distance was about as extensive as its ability to impose its political writ and its taxes. This distance varied not only with the topography but also temporally, with the power and cohesion of the court. The religious “frontier” beyond which orthodoxy could not easily be imposed was therefore not so much a place or defined border as it was a relation to power—that varying margin at which state power faded appreciably.

The wet-rice valleys and the level plains of the typical valley state are not merely topographically flat; they can also be thought of as having been culturally, linguistically, and religiously flattened. The first thing that strikes any observer is the relative uniformity of valley culture compared to the luxuriant diversity of dress, speech, ritual, cultivation, and religious practice to be found in the hills. This relative uniformity is, to be sure, a state effect. Theravada Buddhism, as a would-be universal creed, was very much the religion of a centralizing state compared with the local deities (nat, phi) that predated its spread. Despite their syncretism and incorporation of animist practice, Theravada monarchs, when they could, proscribed heterodox monks and monasteries, outlawed many Hindu-animist rites (many of them dominated by females and transvestites), and propagated what they took to be “pure,” uncorrupted texts.83 The flattening of religious practice was, then, a project of the padi state to ensure that the only other kingdomwide institution of elites besides the crown’s own establishment was firmly under its control. A certain uniformity was also achieved because the larger abbeys were, after all, run by a surplus-appropriating elite that, like the crown itself, thrived best on the rich production and concentrated manpower available at the state core.

Centralized power helps explain a certain level of religious orthodoxy at the core, but it doesn’t fully account for the enormous religious diversity in the hills. The heterodoxy of the hills was itself a kind of state effect. Aside from being beyond the easy reach of the state, the hill populations were more scattered, diverse, and more often isolated. Where there was a Buddhist clergy, it was more dispersed and more decentralized, poorer, and, because it lacked royal patronage or supervision, more dependent on the favor of the local population. If that population was heterodox, as it often was, so too was its clergy.84 Schismatic sects were therefore quite likely to spring up in the hills. If and when they did, they were difficult to repress, being at the margins of state power. Two other factors, however, are decisive. The first is that the combination of scriptural Buddhism and the Jataka stories of the previous lives of the Buddha, not to mention the cosmology of Mount Meru around which palace architecture was organized, provided a strong warrant for withdrawal. Hermits, wandering monks, and forest orders all partook of the charisma and spiritual knowledge that came from a position outside society.85 The second decisive factor is that heterodox sects, proscribed in the valleys, typically moved out of danger and into the hills. Hill demography and geography not only facilitated religious heterodoxy, they also served as a zone of refuge for persecuted sects in the valleys.