Chapter 6

Toxicology

Gary W. Miller

The author would like to thank his colleague Dr. Jason Richardson, who coauthored the first two versions of this chapter. Dr. Miller reports no conflicts of interest related to the authorship of this chapter. Marissa Smith reports no conflicts of interest related to the authorship of the tox boxes.

Introduction to Toxicology

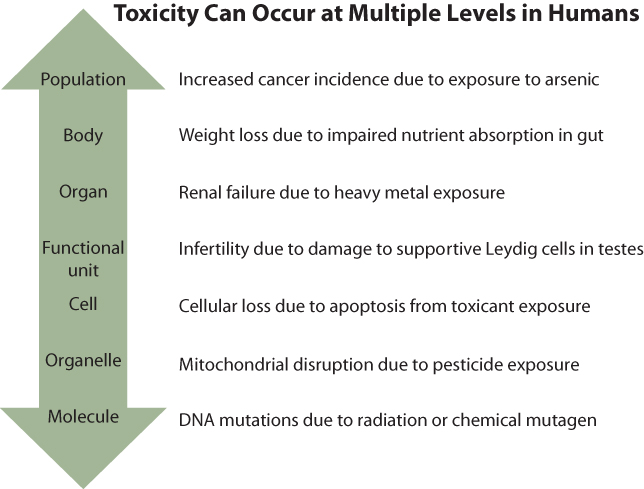

Toxicology (from the Greek toxinos, meaning “poison”) is the study of the adverse effects of chemicals on biological systems. These adverse effects can range from mild skin irritation to liver damage, birth defects, and even death. Chemicals of natural origin are referred to as toxins, while chemicals that result from synthetic processes are referred to as toxicants. The breadth of topics in toxicology requires the field to take an interdisciplinary approach, borrowing techniques and methods from numerous scientific fields including chemistry, pharmacology, pathology, physiology, biochemistry, and more recently, bioinformatics and computational biology. The term biological system can be broadly defined, and so a toxicologist might study the effects of pesticides on insect physiology, of herbicides on plant development, of antibiotics on bacterial growth, or of pollution on an entire ecosystem (the latter has evolved into a separate discipline termed ecotoxicology; see Walker, Sibly, Hopkin, & Peakall, 2012). However, most work in the field of toxicology as it relates to public health is focused on the adverse effects of chemicals on human health. Toxicology is a dynamic field that examines toxic interactions from the level of the molecule all the way to populations (Figure 6.1). This chapter explores how these adverse effects are determined, with an emphasis on the impact of environmental contaminants on human health and the ways in which modern scientific approaches are being applied to ongoing and emerging concerns.

Figure 6.1 Toxicology: From Populations to Molecules

Toxicological effects can be observed at levels ranging from large human populations to specific organs or molecules. The skills and approaches needed to examine each level vary considerably, which necessitates the collaboration of investigators with various areas of expertise.

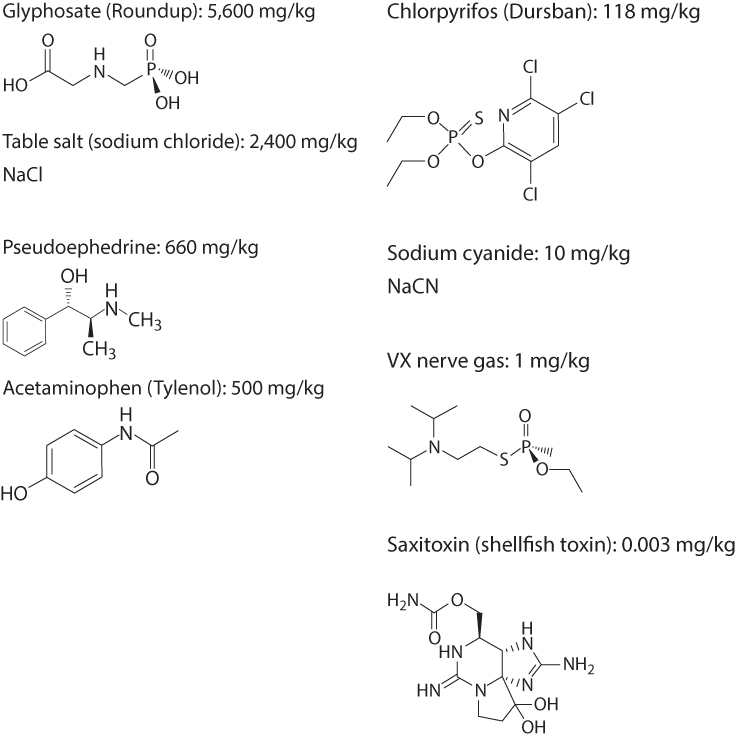

A basic tenet of toxicology is that all substances have the potential to be toxic, not just the poisons that come readily to mind such as strychnine, cyanide, or nerve gas. Paracelsus (born Philippus Aureolus Theophrastus Bombastus von Hohenheim), considered the father of toxicology, was the first to articulate this concept, in the1500s. Of course, all compounds are not equally toxic; some have effects at minuscule doses and others require very high doses (see Figure 6.7 for lethal dose examples). Moreover, while Paracelsus's dictum that “the dose makes the poison” is frequently quoted and often true, new insights suggest a more complex reality—that for some chemicals the maximal toxicity and adverse health effects may occur at very low doses and not increase with increasing dose (as discussed further next).

Figure 6.7 Molecular Structure and LD50 for Eight Chemicals

For example, table salt (sodium chloride) used in moderation is fine in the human diet, but consuming half a cup of salt a day would eventually cause significant electrolyte and kidney problems and possibly death. Conversely, ingestion of even a small amount of potassium cyanide (one gram) can kill a human. It is the job of the toxicologist to determine the relative toxicity of various compounds within the context of anticipated human exposures. This information, when combined with information about the potential utility of a compound and the mechanisms and frequency of exposure, aids regulatory bodies in deciding whether a compound is acceptable for a particular use and what levels of exposure are permissible. For example, the general public (and regulatory agencies) would not tolerate a cold remedy that caused mild liver or kidney damage in 10 percent of users or a food additive that caused cancer in 1 in 1,000 consumers. However, if a new chemotherapeutic agent cured cancer in 80% of the cases, some mild liver or kidney damage might be considered acceptable. Toxicology helps researchers to characterize the adverse effects that form part of the risk-benefit balance for a given chemical, and defining the dose-response relationship is perhaps the most critical aspect of this process (Text Box 6.1).

The dose-response relationship is a quantitative description of the association between exposure to a compound and the toxic effects produced by that exposure. In order for a chemical to exert a toxic effect, the chemical or its active metabolite must reach the site in the body where it can exert its adverse actions, it must do so at a concentration sufficient to cause an effect, and it must persist at this site long enough to exert the effect. In order to assess the toxicity of a given chemical, we need to know not only about the toxic effects it produces but also how an individual might be exposed to the compound and how frequently that exposure occurs (exposure is examined further in Chapter 8). In adults, dermal exposure, ingestion, and inhalation are the major routes by which individuals can be exposed to chemicals. There are also some unusual exposure routes, such as through broken skin or through the eyes.

For the developing embryo or fetus the primary route of exposure is via the placenta. Given the inherent vulnerability of the fetus, in utero exposures via the placenta are of major concern. Major research efforts are under way to better understand the role of the placenta in human health (National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, 2015). After birth, the nutrient-rich breast milk on which infants rely represents another unique source of exposure.

The timing and route of administration can have a significant effect on the toxicity of certain chemicals. For example, the pesticide chlorpyrifos, an organophosphate (see Text Box 6.7), is ten times more toxic via oral administration than via dermal application, and in utero exposures that occur during critical windows of development can have greater overall effects on the health of the developing child than exposures that occur during adolescence.

Several issues must be considered when evaluating a dose-response relationship. First and foremost, it must be known that the response observed is due to the exposure to the compound. Second, the magnitude of the response is generally a function of the dose administered, although these relationships are not necessary linear. Some dose-response curves are very steep, while others resemble an inverted U where maximal toxicity does not occur at the maximal dose or exposure. There also needs be a quantitative method for measuring the response, as discussed in Chapter 8. An additional layer of complexity is that one must consider windows of susceptibility. For example, a particular dose considered to be safe during adulthood could have more deleterious effects during pubertal development. Also, during embryogenesis and fetal development there are particular points in time when chemicals have a much more detrimental effect. Thus “the dose makes the poison” concept needs to take into consideration the temporal and relational aspects that can significantly modify the relationship.

Decades ago many compounds could be detected in the environment or in the body only at relatively high concentrations; for example, in parts per million. Today's detection systems, such as gas and liquid chromatography, mass spectrometry, and atomic absorption spectrometry, are up to a million times more sensitive. As a result, dangerous chemicals are now routinely detected in environmental and human samples, even though present at extremely low levels. It is essential to remember that the biological dose, and not the mere presence of a toxicant in a sample, is the key driver of toxicity. If it takes a concentration of 10 parts per billion of a particular compound to cause any toxicity and if that compound is detected at 1 part per trillion, it is very unlikely to cause an effect. There are several critical questions to ask: How much of the chemical is in the environment? How much of the chemical is in sufficient proximity to a human population to cause exposure? How much of the chemical actually enters the human body? What level of the chemical is necessary to cause an adverse biological effect? As described in Chapter 8, this is the domain of an exposure assessment professional, often working in conjunction with a toxicologist or chemist. The toxicologist is primarily focused on the effects of the chemical of interest once it is in the body.

Toxicology and Environmental Public Health

Toxicology plays a key role in the field of environmental health and public health in general. By focusing on biological mechanisms of action and physiological pathways perturbed by various chemicals, toxicology provides a biological anchor for association studies. This foundation helps to connect environmental concerns to biomedical or clinical strategies for preventing or treating certain conditions. The field of toxicology helps to determine the conditions under which a given compound may cause adverse effects, so it is important for public health professionals to understand key concepts that toxicologists use to make these determinations. Once exposure has occurred, through what routes does the compound enter the body? How much of the compound enters? Where in the body does it go? What does it do once it reaches a particular organ? What physiological effects follow, and if appropriate, what forms of treatment exist? How does the body handle the compound? Does it persist in particular organs? Is it metabolized and excreted in the urine? Armed with the scientific principles of toxicology, the public health professional can find answers to these questions and make prudent decisions on how to manage a particular exposure.

Toxicology is integrated into public health practice in several ways. For example, in providing safe drinking water to a community, it is important to understand both the adverse effects of organisms found in the water and the adverse effects of chemicals used to kill the organisms. As discussed in Chapter 16, chlorination is an effective means of reducing microbiological contamination in water, but chlorine is a dangerous chemical to transport, as explored in Text Box 6.2, and once in drinking water, chlorine can form chlorinated organic compounds known as disinfection by-products. Toxicology can help in identifying these compounds, assessing the risk they pose, and balancing that risk against the risk of microbiological contaminants. In risk assessment as in many areas of health, collaboration between professionals in related disciplines becomes critical in protecting the public.

Another reason that a student in any discipline, but especially environmental health, should develop an appreciation for toxicology is that it is highly relevant to his or her own health. We are exposed to myriad chemicals every day. We ingest chemical residues in the food we eat and we inhale particles in the air we breathe. Many people voluntarily ingest pharmaceutical and recreational drugs, with little or no knowledge of the potential adverse effects. An understanding of toxicology can clarify some of these issues and help us make healthy and informed choices. For example, a student who has a basic understanding of toxicology will realize that a claim that a product—whether a vitamin, a herbal supplement, an agricultural chemical, a medication, or an illegal drug—has no side effects is erroneous and misleading. No agent is completely free of adverse effects, given sufficient doses and circumstances. Similarly, a student who thinks in terms of toxicological action will realize that natural is not the same as safe. Nature produces some highly toxic compounds, such as arsenic, snake venoms, and the carcinogenic toxins produced by some molds. Many psychogenic compounds are completely natural but can have dramatic and long-term adverse effects on brain chemistry. Natural is not necessarily safe.

Toxicant Classifications

Toxic compounds are categorized in three major ways: by chemical class, by source of exposure, and by effects on human health, or more specifically, on specific organ systems. A knowledge of each category helps in understanding toxicology.

Examples of chemical classes are heavy metals, alcohols, and solvents. In essence, the rules of chemistry create the classes, based on such features as functional groups, the presence of metallic elements, and physical properties, such as vapor pressure. Chemical classification may also address physical state; that is, whether a toxicant exists as a liquid, solid, gas, vapor, dust, or fume.

The second system of categorization is functional and is based on the source of exposure. Examples are industrial pollutants, waterborne toxicants, air pollutants, and pesticides. These categories are useful in identifying the source of a problem and are commonly used by environmental health professionals. However, chemicals used in similar ways may vary greatly in their mechanism of toxicity. Because this categorization system groups together chemicals with little chemistry in common, it can obscure connections based on molecular structure. To the toxicologist this system ignores the biological mechanisms that underlie toxicity, even though it is quite relevant when attempting to reduce exposures.

The third system of categorization looks at the organ system in which toxic effects are most pronounced (the target organ). For example, chemicals may target the liver (hepatotoxic), the kidney (nephrotoxic), or the nervous system, whether peripheral or central (neurotoxic). Chemicals that disrupt DNA structure or function are classed as genetic toxicants, mutagens, or carcinogens, depending on their specific effects; carcinogenicity has been a central focus of toxicology, as discussed in Text Box 6.3.

Other organ systems that can be the targets of toxicity include the respiratory system, cardiovascular system, skin, reproductive system, endocrine system, immune system, and blood. Endocrine disruption has been of special interest in recent years, as described in Text Box 6.4. Fetal development is more a process than an organ system, but it too is often viewed as a target of toxic exposures.

The organ system classification of toxicants is commonly used in teaching graduate toxicology, but studying the compounds by chemical class and source has considerable value. When working to protect human health, one needs to consider how a chemical will affect a particular physiological function, whether it be blood pressure, respiration, memory, or urine production. Because each of these functions is controlled by a particular organ system (or systems), organ system classification provides a logical framework for toxicologists; indeed, toxicologists often specialize in the actions of compounds on a specific organ system. Also, even though compounds that affect a specific system may differ in their chemical composition, they often share the features that lead them to target that system. A public health professional should not be satisfied with knowing that a particular substance is toxic, but should ask, What does it do to the body? What system is it disrupting? What are the expected effects? The organ system approach is especially helpful in answering such questions, but if one is trying to determine how a mixture of endocrine-disrupting compounds is impacting reproduction, one also needs to evaluate the chemical characteristics and source of exposures.

To evaluate the toxic effects of a chemical on a particular organ system, one needs a general understanding of how that system works. For example, the main function of the kidneys is to maintain fluid and electrolyte homeostasis in the body. This is accomplished by the reabsorption of material filtered from the blood, including water, ions, and nutrients, and by the excretion of waste material. The kidneys receive a disproportionate amount of the body's blood flow, approximately 20% of cardiac output, considering that they represent less than 1% of the total body weight. This high blood flow, in combination with the numerous transport mechanisms within the kidney designed to reclaim water and nutrients and excrete waste, renders the kidneys exquisitely sensitive to damage by blood-borne toxicants. Of all the cell types in the kidney, one of the most common targets of toxicant-induced injury is the proximal tubule. The proximal tubule is divided into three morphologically distinct segments that vary in structure and function. The proximal tubule reabsorbs 99% of the filtered material. The numerous transport mechanisms in the proximal tubule allow reabsorption of amino acids, sugars, proteins, many electrolytes, and other solutes. Damage to the proximal tubules by toxicant exposure can lead to deterioration of renal function and ultimately renal failure. Exposure to mercury, for example, is known to damage one particular segment of the proximal tubule due to its specific complement of enzymes (see Tox Box 6.2). A toxicologist interested in identifying how mercury alters renal function might isolate proximal tubules in the laboratory, perform toxicity tests on these isolated cellular sections, and compare these animal results with human urine clearance studies and postmortem examination.

Toxicokinetics

It is a useful exercise to track a potentially toxic compound from the environment (from water, air, soil, or food) into and then through the body all the way to its molecular site of action. This study of this process is referred to as toxicokinetics. Suppose that a given compound is generated as a by-product of a particular industrial process. Whereas an exposure assessor measures the concentrations of the compound in the air and an epidemiologist studies the incidence of certain diseases in the surrounding community, the toxicologist is concerned with how the compound gets into the body and what it does once it is there. For example, the compound may be inhaled into the lungs. Once there, it rapidly crosses the alveolar membrane and enters the pulmonary circulation. It travels through the pulmonary vein to the left side of the heart and then circulates throughout the entire body. A large proportion of the compound goes to the liver, where it is activated into a reactive epoxide. This metabolite then finds its way to the kidneys, where it is reabsorbed along with salts and other polar compounds and transported across the cellular membrane of the proximal tubule. There it accumulates and damages cellular macromolecules.

If the toxicologist can show that this compound damages the kidney and if the epidemiologist identifies an exposure-related increase in the incidence of renal failure in a population, regulatory steps may be taken to eliminate or limit the use of this compound. Toxicology helps researchers to provide biological plausibility to association studies conducted in large human populations. Toxicology can also be very useful in monitoring the development of new compounds. If a toxicologist shows that a new compound has an effect in rats or mice similar to the effect of a known toxicant, the new compound is likely to show the same toxicity in humans, so a manufacturer would be wise to discontinue development of that compound. Thus the understanding of mechanisms can lead to the development of safer chemicals and drugs. In fact, toxicology can inform developments in green chemistry, the design of chemical products and processes that reduce or eliminate the use or generation of hazardous substances.

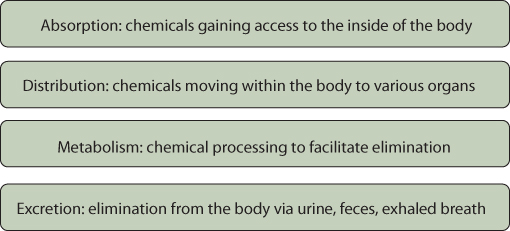

After a person is exposed to a particular chemical (the term xenobiotic is used to describe chemicals that are foreign to the body), a sequence of steps determines the response to the chemical: absorption into the body, distribution throughout the body, metabolism, and excretion (Figure 6.5). Each of these steps can impact the toxicity of the chemical by influencing where it goes, how it can be chemically modified, and how long it stays in the body. This toxicokinetic sequence is described in the following sections.

Figure 6.5 Key Steps in Toxicokinetics

Absorption

Once a person has come in contact with a toxic compound, that compound may gain access to the body. It is not enough for this compound to contact the skin, be inhaled into the lungs, or enter the intestinal track; it must actually traverse the biological barrier. Each of these pathways exhibits characteristics that affect absorption. One of the most important characteristics affecting the entire process of toxicokinetics is solubility. Compounds that readily dissolve in water are called hydrophilic (meaning “water loving”), and compounds that dissolve in lipids instead are called hydrophobic (“water hating”) or lipophilic (“fat loving”). Recall from chemistry the terms polar and nonpolar used to describe chemicals. Asymmetric molecules, such as water or chemicals with long side chains and functional groups, are often polar, whereas symmetric molecules with minimal added groups, such as benzene, are nonpolar. Salad dressing illustrates this property; the oil (hydrophobic) and the vinegar (hydrophilic) don't readily mix. The octanol:water coefficient (termed Kow) is a way chemists measure the relatively solubility of chemicals. Urine is composed primarily of water, explaining how water-soluble chemicals can be excreted in urine. Furthermore, if one considers that most of the biological barriers that exist in our bodies are composed of lipids, the ability of chemicals to traverse these barriers has much to do with whether or not they are fat soluble.

The gastrointestinal system is designed for nutrient absorption, and it has a large surface area with numerous transport mechanisms. The presence of gut bacteria (the microbiome) can affect absorption (see Text Box 6.5). Many toxicants can take advantage of this system to enter the body. Toxicants can also be absorbed through the pulmonary alveoli. The alveoli are the functional units of the lung and the sites of gas exchange between the air and the blood supply. The skin represents a third key route of toxicant exposure. Many occupational exposures occur via this route. Although intact skin offers an effective barrier against water-soluble toxicants, fat-soluble toxicants can readily penetrate the skin and enter the bloodstream.

Distribution

Once in the bloodstream a toxicant can be distributed throughout the body. If the toxicant is fat soluble, it is often carried through the aqueous environment of the bloodstream in association with blood proteins, such as albumin. Toxicants generally follow the laws of diffusion, moving from areas of high concentration to areas of low concentration. Chemicals absorbed in the intestine are shunted to the liver through the portal vein, in a first-pass process, and may undergo metabolism promptly. A limited number of chemicals may be excreted unchanged into bile or by the kidneys into urine.

Metabolism

Once in the body most toxicants undergo metabolic conversion, or biotransformation, a process mediated by enzymes. The majority of biotransformation reactions occur in the liver, which is rich in metabolic enzymes. However, nearly all cells in the body have some capacity for metabolizing xenobiotics. In general, metabolic transformations lead to products that are more water soluble and less fat soluble. The metabolic product is therefore more soluble in urine, which facilitates its excretion. For example, benzene is oxidized to phenol (see Tox Box 7.1, in Chapter 7), and glutathione combines with halogenated aromatics to form nontoxic and more polar mercapturic acid metabolites. However, metabolic transformations sometimes yield increasingly toxic products. One example is the oxidation of methanol (a relatively nontoxic compound in its native form) to formaldehyde and formic acid (a compound that is quite toxic to the optic nerve and causes blindness).

Traditionally, metabolic transformations are divided into four categories: oxidation, reduction, hydrolysis, and conjugation. Transformations in the first three of these reaction categories, known as phase I reactions, generally increase the polarity of substrates and can either increase or decrease toxicity by revealing functional sites. Many compounds undergo bioactivation at this stage. In conjugation, the only phase II reaction, polar groups are added to the products of phase I reactions. Most chemicals pass sequentially through these two phases, as illustrated by acetaminophen (Figure 6.6), although some are directly conjugated. Many examples of each type of reaction can be found in standard toxicology textbooks (such as Klaasen, 2013).

Figure 6.6 The Metabolism of Acetaminophen

Acetaminophen (or paracetamol, as it is known in Europe) is one of the most commonly used over-the-counter medications. The drug can undergo hydroxylation (phase I) followed by glutathione conjugation (phase II), or also directly undergo glucuronidation or sulfation (phase II). When insufficient levels of glutathione are available, a very toxic metabolite can build up in the liver and lead to significant toxicity.

As mentioned earlier, various combinations of these reactions may be assembled in response to the same toxicant. Metabolic strategies for a particular toxin may vary widely among species, so an animal study, to be applicable to humans, should use a species with pathways similar to those of humans. The most prominent enzyme system for performing phase I reactions is the cytochrome system. These enzymes are found in the endoplasmic reticulum of hepatocytes and other cells. In recent years, advances in molecular biology have greatly expanded our understanding of a particular enzyme complex, cytochrome P450. Dozens of distinct P450 genes have been identified and sequenced. They have been grouped into eight distinct families, and for many, specific functions have been identified. For example, the enzyme CYP1A1 metabolically activates polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs); the enzyme CYP2D6 is responsible for metabolizing such medications as beta-blockers and tricyclic antidepressants, while the enzyme CYP2E1 bioactivates vinyl chloride, methylene chloride, and urethane. Polymorphism in the genes that code for various P450 proteins results in different metabolic phenotypes, explaining why people may vary widely in their responses to similar medications or chemical exposures. Chapter 7 explores this key principle in detail.

Disruption of enzymatic function is a common mechanism of toxicity, as when organophosphate pesticides compete with acetylcholine for the binding sites on cholinesterase molecules (see Tox Box 18.1, in Chapter 18), or when metals such as beryllium compete with magnesium and manganese for enzyme ligand binding. For example, methyl alcohol is oxidized first by the enzyme alcohol dehydrogenase to formaldehyde, and then, by aldehyde dehydrogenase, to formic acid, which is toxic to the optic nerve. This process can be blocked by large doses of ethanol, which competes for enzyme binding sites and slows the formation of the toxic metabolite. The drug fomepizole acts in the same way, by selectively inhibiting alcohol dehydrogenase. This drug has been used to treat ethylene glycol poisoning, preventing the formation of the toxic metabolites glycolic acid and oxalic acid.

The enzyme systems that metabolize xenobiotics are not static. When the demand is high, their synthesis can be enhanced in a process called enzyme induction. The resulting increase in enzyme activity helps the organism respond to subsequent exposures, not only to the original xenobiotic but to similar substances as well. DDT and methylcholanthrene are examples of substances known to induce metabolic enzymes. People vary in their capacity for biotransformation in several ways. Two mechanisms of variation have already been mentioned: genetic factors and enzyme induction. Other factors that account for interindividual differences in metabolism are general health, nutritional status, and concurrent medications.

Excretion

Biotransformation tends to make compounds more polar and less fat soluble; the beneficial outcome of this process is that toxins can be more readily excreted from the body. The major route of excretion of toxins and their metabolites is through the kidneys. Serum is filtered through the kidneys, key nutrients and most of the water are reclaimed, and some chemicals are actively secreted during this process. The daily volume of filtrate produced is about 200 liters—five times the total body water—in a remarkably efficient and thorough filtration process.

A second major organ of excretion is the liver. The liver occupies a strategic position because the portal circulation promptly delivers compounds to it following gastrointestinal absorption. Furthermore, the generous perfusion of the liver and the discontinuous capillary structure within it facilitate filtration of the blood. Thus excretion into the bile is potentially a rapid and efficient process. Toxicants that are secreted with the bile enter the gastrointestinal tract and, unless reabsorbed, are secreted with the feces. Materials ingested orally and not absorbed and materials carried up the respiratory tree and swallowed are also passed with the feces. All of this may be supplemented by some passive diffusion through the walls of the gastrointestinal tract, although that is not a major mechanism of excretion.

Volatile gases and vapors are excreted primarily by the lungs. The process is one of passive diffusion, governed by the difference between plasma and alveolar vapor pressure. Volatiles that are highly fat soluble tend to persist in body reservoirs and take some time to migrate from adipose tissue to plasma to alveolar air. Less fat-soluble volatiles are exhaled fairly promptly, until the plasma level has decreased to that of ambient air. Ethanol is amphipathic, meaning that it has both lipophilic and hydrophilic properties, allowing it to dissolve readily in liquids and to partition into lipid membranes, resulting in accumulation in lipid stores. As it slowly but predictably moves out of lipid stores, it is liberated into exhaled breath. This is the premise behind the use of the Breathalyzer to determine one's level of intoxication. Interestingly, the alveoli and bronchi can sustain damage when a vapor such as gasoline is exhaled, even when the initial exposure occurred percutaneously or through ingestion.

Other routes of excretion, although of minor significance quantitatively, are important for a variety of reasons. Excretion into mother's milk obviously introduces a risk to the infant, and because milk is more acidic (pH 6.5) than serum, basic compounds are concentrated in milk. Moreover, owing to the high fat content of breast milk (3% to 5%), fat-soluble substances such as DDT can also be passed to the infant. Some toxins, especially metals, are excreted in sweat or laid down in growing hair, which may be of use in diagnosis. Finally, some materials are secreted in the saliva and may then pose a subsequent gastrointestinal exposure hazard.

Testing Compounds for Toxicity

How does a toxicologist determine that one compound is more toxic than another? Several decades ago toxicologists used a rather crude method for determining the relative toxicity of compounds. By exposing laboratory animals to compounds and determining the dose that killed half the animals, they calculated the “lethal dose for 50%,” or LD50, an index that allowed comparisons among several unrelated compounds (Text Box 6.6).

Although crude, the LD50 has some important scientific strengths. The exposure is well defined (unlike the exposure in most human situations), the outcome is unambiguous, the measure can be applied across different compounds, and it can lead to a useful practical conclusion: if a compound is lethal at very low doses then human exposures should be prevented or strictly controlled. In today's modern laboratories, toxicologists focus more on how chemicals exert their toxic effects, such as through DNA mutation, enzyme inhibition, or altered nerve firing. This allows much of the testing to occur in test tubes, petri dishes, and 96- or 384-well trays. Experiments can focus on the effects of numerous chemicals on specific molecular or cellular targets. Such insight allows scientists to focus efforts when more complex experimental models like isolated organs or intact animals are needed. In recent years, questions about animal testing have been raised, and alternative methods are being actively pursued, as discussed in Text Box 6.7.

From Regulatory Toxicology to Public Health Policy

Toxicology can generate vast amounts of data on how chemicals affect human health, but in order to protect public health this information must be integrated into public policy. These issues fall into the domain of regulatory toxicology, which is closely aligned with the field of risk assessment (see Chapter 27). The basic principles of the dose-response relationship described earlier in this chapter are a critical part of that process. Through evaluation of dose-response curves generated during laboratory testing, several values can be determined that can be a basis for regulatory decisions. One of the most important values determined in such studies is the no-observed-adverse-effect level, or NOAEL. This is the highest dose administered for which no harmful effects are observed. The NOAEL is used by the Environmental Protection Agency in establishing the reference dose (RfD), which is an estimate of the daily oral dose of a chemical that is likely to be without appreciable risk for an individual over a lifetime of exposure. Results from toxicology studies directly impact a variety of regulatory and other policy approaches.

Public health policy to protect people from harmful chemicals is distributed across a series of agencies, defined by a range of laws, and as described below, far from complete. Policies are implemented according to the domains of exposure, including the workplace, the general environment, consumer goods, foods, and water.

Some of the highest exposures to chemicals occur in the workplace. In that setting, OSHA has regulatory responsibility. OSHA's approach to protecting workers from chemicals is explored in Chapter 21.

For nonworkplace exposures, the major piece of protective legislation in the United States is the Toxic Substances Control Act (TSCA) of 1976, which authorizes the EPA to regulate chemical substances and mixtures. Under TSCA, the EPA has three major responsibilities: gathering information on new and existing chemicals being manufactured in the United States, assembling data on chemical risks, and regulating chemicals that present an “unreasonable risk of injury to health or the environment.” The EPA had a formidable job when it first implemented the TSCA. More than 60,000 chemicals were already in commercial use, and the law required no testing, so these chemicals were presumed to be safe and were grandfathered in. With chemicals innocent until proven guilty, the EPA bears the burden of proof that a chemical poses an “unreasonable risk.” Nor does the TSCA require premarket testing for new chemicals; it only requires manufacturers to provide basic chemical information, along with any toxicity information they have. This is in sharp contrast to pharmaceutical regulation, which requires evidence of safety before a product is brought to market. The EPA can regulate only when the available data demonstrate toxicity—providing a strong incentive for manufacturers not to conduct toxicity testing.

Critics charge that under the TSCA, the EPA cannot require toxicity testing unless it knows that a chemical is toxic, but without such testing, a determination of toxicity is impossible—a regulatory Catch-22. And regulation has proven as difficult as data collection. When the EPA did try to regulate a well-established hazard, asbestos, in the 1980s, a court struck down the EPA's action, ruling that the agency had failed to meet TSCA's high burden of proof (“substantial evidence” of an “unreasonable risk”) and had not proposed the “least burdensome” approach to regulation. Consequently, the EPA has regulated only five chemicals under the TSCA in the decades since that law passed—decades during which over 20,000 new chemicals were brought to market. The law is widely considered ineffective (U.S. Government Accountability Office [GAO], 2005, 2007; Markell, 2010; Vogel & Roberts, 2011).

During the first decade of the twenty-first century, European nations developed a comprehensive approach to chemical management called REACH (Registration, Evaluation, Authorization and Restriction of Chemicals). A key feature of REACH is the requirement for premarket testing of chemicals, placing the burden of proof of safety on manufacturers (GAO, 2005, 2007; Williams, Panko, & Paustenbach, 2009). Moreover, some U.S. states began regulating chemicals on their own; examples include Washington State's Children's Safe Products Act and Maine's Toxic Chemicals in Children's Products Act; both passed in 2008. These developments have spurred calls for TSCA reform from across the political spectrum (Applegate, 2008; Denison, 2009; Vogel & Roberts, 2011), including from the EPA itself (www.epa.gov/oppt/existingchemicals/pubs/principles.html). Key provisions of TSCA reform include expanded safety reviews and testing of chemicals, increased access to information regarding chemical toxicity, and protection of vulnerable populations (Applegate, 2008); by late 2015, Congress was close to passing such a bill, the Lautenberg Act.

Other laws regulate chemical exposures in other ways. As described in Chapter 18, the Federal Insecticide, Fungicide, and Rodenticide Act (FIFRA) provides the basis for the EPA to regulate pesticides, principally through issuing registration—in effect a license for a particular pesticide to be used in particular ways. FIFRA has stronger provisions than TSCA for premarket evaluation, data generation, product labeling, and the EPA's ability to suspend or cancel a pesticide's registration—four key features of regulatory strategy. Under another law, the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act (FFDCA), the EPA sets maximum residue levels, or tolerances, for pesticides used in or on foods or animal feed. The regulatory framework under FFDCA is health based (“reasonable certainty of no harm”), with far less emphasis on risk-benefit analysis, a sharp contrast with the TSCA. Of note, FFDCA is also the law that enables the FDA to regulate the safety of foods, food additives, medications, and cosmetics. A third law, the Food Quality Protection Act (FQPA), amended FIFRA and FFDCA in 1996, setting tougher safety standards for new and old pesticides and creating uniform requirements regarding processed and unprocessed foods. FQPA includes several provisions that incorporate toxicological knowledge. First, assessment must include aggregate exposures including all dietary exposures, drinking water, and nonoccupational (e.g., residential) exposures. Second, when assessing a tolerance, EPA must consider cumulative effects and common modes of toxicity among related pesticides, the potential for endocrine disruption effects, and an appropriate safety factor. Third, EPA must incorporate a tenfold safety factor in setting tolerances, reflecting the special vulnerability of infants and children.

Still another law, the Emergency Planning and Community Right-to-Know Act (EPCRA) of 1986, was passed in the aftermath of one of the world's worst chemical disasters: the 1984 release from a Union Carbide plant in Bhopal, India, of forty tons of methyl isocyanate (MIC), killing as many as 5,000 people and injuring ten times that number. EPCRA addressed emergency preparedness for chemical disasters, defining local-level responsibilities and procedures. It also required industry to report on the storage, use, and releases of hazardous chemicals to federal, state, and local governments, and created an important repository of data, the Toxics Release Inventory (TRI). The TRI is not a complete inventory of hazardous chemical use—for example, small users such as dry cleaners are not required to report—but it represents a key approach to chemical protection: namely that disclosure and transparency lead to accountability, and ultimately to the adoption of cleaner, safer practices (Khanna, Quimio, & Bojilova, 1998)

While these laws are in some respects complementary, there is also a fragmented quality to them—intensified by the fact that still other laws regulate specific media such as air (the Clean Air Act; see Chapter 13) and water (the Clean Water Act and the Safe Drinking Water Act; see Chapter 16). For instance, if a pesticide is found to contaminate a river that supplies a community's drinking water, is this a concern for FIFRA or the Safe Drinking Water Act (Franklin, 2011–2012)?

Summary

Toxicology addresses the adverse effects of chemicals in terms of an exposure and effect sequence—from exposure to absorption to distribution to metabolism to excretion—and analyzes the end effects on organs and physiological systems that may occur during this process. Identifying mechanisms or pathways of toxicity can help to establish a biological basis for regulation. This knowledge is directly informative to regulators and others who work to identify the safest chemicals for our use and to set acceptable levels of exposure for chemicals that may be dangerous.

Key Terms

- absorption

- The movement of a chemical across a biological barrier, such as skin, intestinal lining, or alveoli.

- alcohol dehydrogenase

- An enzyme involved in the conversion of ethanol to acetaldehyde; the primary means of metabolizing ingested alcohol.

- animal testing

- The process of modeling the toxic effects of chemicals by exposing laboratory species in a control setting.

- bioactivation

- A metabolic process that alters a chemical in a way that increases its reactivity.

- biotransformation

- A metabolic process that changes the properties of a given chemical.

- carcinogenesis

- The process of cancer development, which typically includes a series of mutations to tumor-promoting and tumor-suppressing genes.

- carcinogens

- Chemicals that can induce cancer.

- conjugation

- The addition of chemical entities to increase the solubility and excretion of a given compound.

- cytochrome P450

- Enzymes involved in the metabolism of chemicals, found at high levels in the liver.

- dermal exposure

- The process by which a chemical gains entry to the body via the skin.

- distribution

- The movement of a chemical throughout the body.

- dose-response relationship

- The graphical representation of increasing exposure to a chemical compared to the biological effects.

- ecotoxicology

- The study of the adverse effects of chemicals on the environment or an ecosystem.

- Emergency Planning and Community Right-to-Know Act (EPCRA)

- A 1986 law aimed at preparing local communities and governments for potential exposures to toxic chemicals by providing access to information on the nature of the health risks posed by the chemicals.

- endocrine disruptors

- Exogenous agents that interfere with the production, release, transport, metabolism, binding, action, or elimination of natural hormones, such as estrogen, androgens, and the thyroid hormone, that are responsible for the maintenance of homeostasis and the regulation of developmental processes.

- enzyme induction

- A process that results in an increased expression of proteins involved in metabolizing a particular class of chemicals.

- epigenetic

- A term describing modifications to DNA that do not involve a change in the primary sequence of nucleotides.

- excretion

- The process by which a chemical exits the body.

- Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act (FFDCA)

- A law initially passed in 1938 and designed to protect consumers from hazards found in ingested or applied products.

- Federal Insecticide, Fungicide, and Rodenticide Act (FIFRA)

- A law initially passed in 1910 to protect users, consumers, and the environment from risks associated with pesticide use.

- Food Quality Protection Act (FQPA)

- A law passed in 1996 that requires health assessment–based changes to the laws governing the use of pesticides.

- genetic toxicants

- Chemicals that damage DNA or the machinery involved in maintaining DNA integrity.

- green chemistry

- A field devoted to the generation of materials in ways that focus on minimizing adverse effects on the environment and human health.

- hepatotoxic

- Inducing adverse effects in the liver.

- hydrolysis

- A chemical process that uses water to break apart chemical bonds.

- hydrophilic

- Polar, or water soluble.

- hydrophobic

- Nonpolar, or fat soluble.

- ingestion

- The introduction of a compound into the digestive tract via the mouth.

- inhalation

- The introduction of a gas or particle into the lungs via the airway.

- initiation

- An early step in the process of carcinogenesis that typically involves DNA mutation.

- LD50

- The dose at which one half of the test group dies in a certain period of time. LD stands for “lethal dose.”

- metabolism

- The processing of chemicals within the body; it can involve activation, inactivation, breakdown, or conjugation with other constituents.

- metastasis

- Movement of cancerous cells from the original site of the tumor or growth, typically involving distribution within the bloodstream or lymphatic system.

- microbiome

- The compilation of microbial organisms that live within the intestines, on the skin, and within various mucus membranes.

- mutagens

- Chemicals that can induce physical alterations in the structure of DNA.

- nephrotoxic

- Inducing adverse effects in the kidney.

- neurotoxic

- Inducing adverse effects in the central or peripheral nervous system.

- no-observed-adverse-effect level

- The highest exposure at which there are no discernable negative biological effects of a certain chemical.

- oxidation

- A metabolic process that involves the introduction of molecular oxygen to alter a chemical.

- phase I reaction

- A metabolic process that modifies a chemical; hydroxylation, oxidation, and reduction are common mechanisms.

- phase II reaction

- A metabolic process that generally involves the addition of side chains or functional groups (glucoronide, glutathione, methyl groups).

- progression

- A step in carcinogenesis that involves the acquisition of traits that increase the aggressive nature of a tumor.

- promotion

- A step in carcinogenesis that involves the expansion of the cells containing a particular mutation.

- REACH (Registration, Evaluation Authorization, and Restriction of Chemicals)

- The European approach to chemical management, entered into force in 2007. REACH includes many precautionary provisions such as the requirement for premarket testing of chemicals.

- reduction

- A metabolic process that involves the gain of an electron.

- reference dose (RfD)

- A level of daily oral exposure to a chemical, such as a pesticide, that has no apparent adverse effects on humans; the RfD is used in setting regulatory guidelines.

- registration (of pesticides)

- The process that industries must follow to inform the EPA of any intended use of chemicals to control unwanted species in agricultural or consumer settings.

- regulatory toxicology

- The subspecialty that focuses on the use of laboratory and epidemiological data to guide the development and enforcement of laws aimed at protecting consumers and the environment from chemicals.

- target organ

- The specific physiological system affected by a given toxicant.

- tolerance

- An EPA-set limit on the amount of residual pesticide that can be present in foods and consumer goods.

- Toxic Substances Control Act (TSCA)

- The 1976 law that governs the uses of chemicals, excluding drugs, cosmetics, and food.

- toxicant

- A synthetic compound that exerts notable adverse effects on a biological system.

- toxicokinetics

- The study of the movement of toxic compounds from the environment into and within a target organism.

- toxicology

- A field of science dedicated to the study of the adverse effects of chemicals on biological systems.

- Toxics Release Inventory (TRI)

- A database maintained by the EPA that provides information on incidents involving the introduction of hazardous chemicals into the environment.

- toxin

- A compound of natural origin that exerts notable adverse effects on a biological system.

- xenobiotic

- A chemical that is foreign to a given organism.

Discussion Questions

- Historically, toxicology testing has been focused on one chemical at a time, yet we are rarely exposed to chemicals in isolation. Why do you think this approach to testing has been taken? What challenges may be involved in studying mixtures of chemicals?

- If a company claims that its product is “all natural,” does that mean it is safe? Why or why not?

- What chemicals do you think are most harmful to your own health? How are you exposed? How could you go about determining whether or not each of these chemicals was harmful to you?

- The REACH legislation mandates a reduced reliance on animal testing, and Europe has long banned animal testing for cosmetics. Are there any potential negative consequences that could occur with the move away from animal testing?

- Manufacturers removed bisphenol A from most of their products over the past few years. What replaced it? What type of testing did the replacement chemical undergo?

References

- Applegate, J. S. (2008). Synthesizing TSCA and REACH: Practical principles for chemical regulation reform. Ecology Law Quarterly, 35(4), 721–770.

- Carson, R. (1962). Silent spring. Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

- Crews, D., Gillette, R., Scarpino, S. V., Manikkam, M., Savenkova, M. I., & Skinner, M. K. (2012). Epigenetic transgenerational inheritance of altered stress responses. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 109(23), 9143–9148.

- Denison, R. A. (2009). Ten essential elements in TSCA reform. Environmental Law Reporter, 39, 10020–10028.

- Dickerson, S. M., & Gore, A. C. (2007). Estrogenic environmental endocrine-disrupting chemical effects on reproductive neuroendocrine function and dysfunction across the life cycle. Reviews in Endocrine & Metabolic Disorders, 8(2), 143–159.

- Franklin, C. (2011–2012). FIFRA v. the courts: Redefining federal pesticide policy, one case at a time. Natural Resources & Environment, 26, 18.

- Hinterthuer, A. (2008). Safety dance over plastics. Scientific American, 299(3), 108, 110–111. Retrieved from http://www.scientificamerican.com/article/just-how-harmful-are-bisphenol-a-plastics

- Khanna, M., Quimio, W., & Bojilova, D. (1998). Toxic release information: A policy tool for environmental protection. Journal of Environmental Economics and Management, 36(3), 243–266.

- Klaasen, C. D. (Ed.). (2013). Casarett and Doull's Toxicology: The basic science of poisons (8th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill.

- Markell, D. (2010). An overview of TSCA, its history and key underlying assumptions, and its place in environmental regulation. Washington University Journal of Law and Policy, 32(1), 333–375.

- Meeker, J. D. (2012). Exposure to environmental endocrine disruptors and child development. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine, 166(6), E1–7.

- National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. (2015). The Human Placenta Project. Retrieved from http://www.nichd.nih.gov/research/HPP

- Tang, W. H., Wang, Z., Levison, B. S., Koeth, R. A., Britt, E. B., Fu, X.,…Hazen, S. L. (2013). Intestinal microbial metabolism of phosphatidylcholine and cardiovascular risk. New England Journal of Medicine, 368, 1575–1584.

- U.S. Government Accountability Office. (2005). Chemical regulation: Approaches in the United States, Canada, and the European Union (GAO-06-217R). Washington, DC: Author.

- U.S. Government Accountability Office. (2007). Comparison of U.S. and recently enacted European Union approaches to protect against the risks of toxic chemicals (GAO-07-825). Washington, DC: Author.

- Vogel, S. A., & Roberts, J. A. (2011). Why the Toxic Substances Control Act needs an overhaul, and how to strengthen oversight of chemicals in the interim. Health Affairs, 30(5), 898–905.

- Walker, C. H., Sibly, R. M., Hopkin, S. P., & Peakall, D. B. (2012). Principles of ecotoxicology (4th ed.). Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press.

- Wenck, M. A., Van Sickle, D., Drociuk, D., Belflower, A., Youngblood, C., Whisnant, M. D.,…Gibson J. J. (2007). Rapid assessment of exposure to chlorine released from a train derailment and resulting health impact. Public Health Reports, 122(6), 784–792.

- Williams, E. S., Panko, J., & Paustenbach, D. J. (2009). The European Union's REACH regulation: A review of its history and requirements. Critical Reviews in Toxicology, 39(7), 553–575.

For Further Information

Books and Monographs

- Anastas, P. T., & Warner, J. C. (2000). Green chemistry: Theory and practice. New York: Oxford University Press.

- International Agency for Research on Cancer. (2015). IARC Monographs on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans (Web site). http://monographs.iarc.fr/ENG/Classification

- Roberts, S. M., James, R. C., & Williams, P. L. (Eds.). (2015). Principles of toxicology: Environmental and industrial applications (3rd ed.). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

Organizations

- Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry (ATSDR): http://www.atsdr.cdc.gov. ATSDR maintains data on hazardous chemicals at http://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/toxfaq.html and http://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/toxpro2.html

- Center for Alternatives to Animal Testing (CAAT) at Johns Hopkins University: http://caat.jhsph.edu

- Society of Toxicology: http://www.toxicology.org. The Society of Toxicology is a professional organization that promotes the use of toxicology to improve human health.