Chapter 7

Genes, Genomics, and Environmental Health

David L. Eaton and Christopher M. Schaupp

Dr. Eaton and Mr. Schaupp report no conflicts of interest related to the authorship of this chapter. Disclosures by Dr. Frumkin, who wrote Tox Box 7.1, appear in the front of this book, in the section titled “Potential Conflicts of Interest in Environmental Health: From Global to Local.” Dr. Woods reports no conflicts of interest related to the authorship of Text Box 7.2.

“Why me, Doc?” is not an uncommon question when you or a family member has been diagnosed with a dreaded but all too common disease, such as cancer or Alzheimer's disease. “Was it something bad in my genes?” “Something I ate?” “Perhaps something I was exposed to in my workplace?” The answers to these very personal questions have their roots in the age-old debate over whether nature or nurture makes us who and what we are. Today, with the entire human genome sequence available and a plethora of modern techniques ready to probe it, the answer to this nature versus nurture question should be at hand. However, as is commonly the case, it is not that simple.

In this chapter you will learn about what it is that nature (your genes) contributes to your life as well as some ways in which the world around you (your environment) has an impact on your health. Importantly, you will also learn how various genes and environmental factors interact in complex ways to increase or decrease your risk of developing some unwanted outcome, such as a disease, an adverse drug reaction, or an allergic response to something in your food, air, or water. So in the rest of this chapter you will learn from numerous examples about gene-environment interactions (GxE interactions). But first, you need some fundamental understanding of how genes operate, and how environmental exposures can modify your health either directly (see Chapter 6, on toxicology) or by interacting with your genes.

Fundamental Concepts of Genetics and Genomics

Basic Components of a Gene and a Genome

Every living organism uses an elegant and seemingly simple string of chemicals, called bases, hooked together end to end to form deoxyribonucleic acid, or DNA. Just four different bases make up DNA: thymine (T), guanine (G), cytosine (C), and adenine (A). Each of these bases has a 5-carbon sugar molecule, called deoxyribose, attached to it. When the sugar is attached to the base, the combined molecule is called a nucleotide. But in the cell, this string of nucleotides called DNA is actually two complementary strands of DNA woven together in the famous double helix first described by Watson and Crick in 1954. The elegance of DNA is that the four bases pair up in a specific way: A always pairs with T, and G always pairs with C. So, if one strand of DNA has the nucleotide sequence CGTCCGAT, you can immediately deduce that the corresponding strand that pairs with this has the sequence GCAGGCTA. The order of bases is what determines an individual's genetic code. Approximately 3 billion base pairs constitute a human genome. If you were to grab one end of a single molecule of DNA and stretch it out, those 3 billion base pairs that make up your genome would be over 1 meter long! And every cell in your body has an exact copy of all 3 billion base pairs in the exact same order. Imagine a single book, 600,000 pages long (with each base representing 1 character, and 5,000 characters on a single-spaced page). But even more amazing than packaging a 600,000 page book of code into each cell is that only a small fraction of that information is actually used in any given cell or tissue. A liver cell expresses a different set of genes than a brain cell or kidney cell.

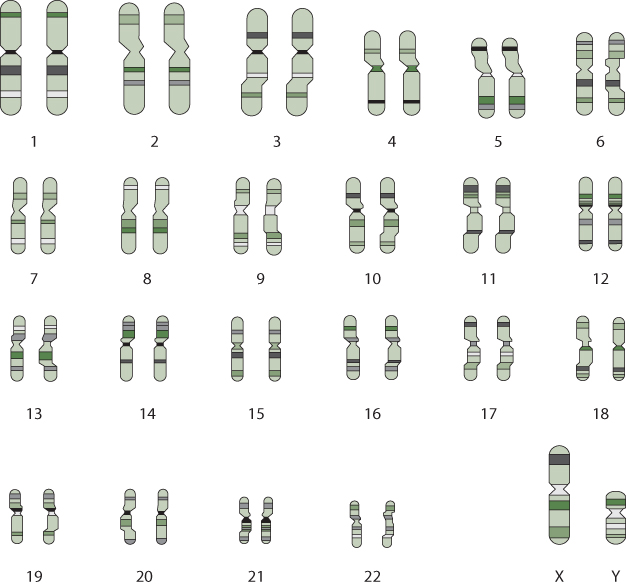

So what is a gene? A gene is a specific sequence of nucleotides that contains information and that controls some function in the cell, such as forming a protein. Within the continuous 3 billion base pairs (nucleotides) in a molecule of DNA are “start” and “stop” signals that constitute the boundaries of each gene. There are approximately 24,000 genes in the human genome. That is a startlingly small number of genes, given the complexity of human life! The genome and the genes within it, however, are not packaged as a single long chain of DNA, but rather in discrete units called chromosomes, and every chromosome is part of a matched set of two. There is a total of forty-six chromosomes. Forty-four of these are present as duplicates; thus there are twenty-two autosomes and two more chromosomes that are sex-specific—the X chromosome (female) and the Y chromosome (male) (Figure 7.1). One chromosome in each of the twenty-two autosomes comes from the mother and one comes from the father. Females also receive an X chromosome from both mother and father, whereas males also receive an X chromosome from the mother and a Y chromosome from the father.

Figure 7.1 The Human Genome

The genome consists of 3 billion base pairs of nucleotides, packaged in discrete units called chromosomes. There are 23 pairs of chromosomes—22 pairs are autosomes, and 2 consist of sex chromosomes (XX or XY). Chromosomes vary in size (chromosome 1 being the largest with about 4,000 genes, and the Y chromosome being the smallest, with 458 genes).

Within each of these chromosomes are packaged hundreds to thousands of individual genes. Since a child receives half of his or her chromosomes from the mother and the other half from the father, every child has two copies of every gene, a fifty-fifty mixture from the two parents. Since you have two copies of every gene, it is convenient to have a term that refers to just one of these copies. The term allele is used to identify the single gene from each parent. So while the two chromosomes of a pair carry very similar DNA, the two alleles of any given gene are not necessarily identical in sequence. If one of these alleles is different in sequence from the common form, it is called the variant allele. The reason why two people don't look, act, or sound exactly alike is in part the result of small differences in the sequence of genes, and in how much of the gene is expressed. We will discuss how the regulation of gene expression occurs later.

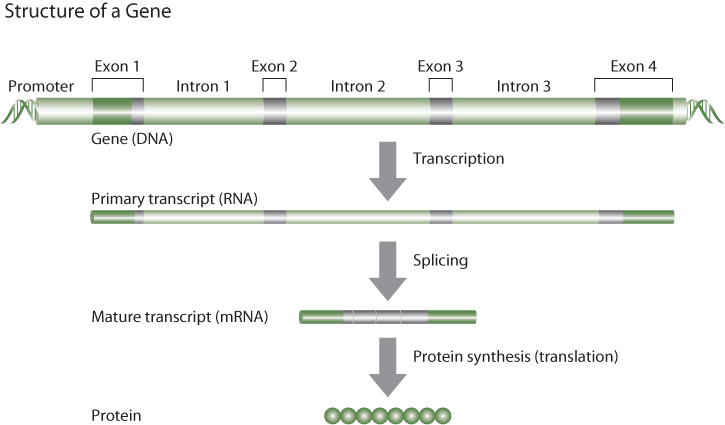

The basic structure of a gene is shown in Figure 7.2. The core function of most genes is to make proteins, which are the business end of biology. Almost all the cellular work in an organism is done by proteins. Proteins are constructed by linking amino acids together in a specific order. There are twenty-one different amino acids that make up the proteins in the body. The order of the amino acids is determined explicitly by the order of the bases in DNA.

Figure 7.2 The Basic Structural Elements of a Gene

But there is an intermediary between the sequence of DNA in a gene and the protein product that is coded by that gene. That intermediary is ribonucleic acid, or RNA. Like DNA, RNA is made up of four bases, each coupled with a sugar (ribose). The bases in RNA include three of the same bases found in DNA: guanine (G), adenine (A), and cytosine (C). But RNA uses the base uracil (U) in place of thymine. Thus RNA is copied from DNA based on the same base-pairing principles as apply in double-stranded DNA. This process is known as gene transcription (Figure 7.2). There are several different types of RNA, each with its own function. The RNA that codes directly for proteins is called messenger RNA (mRNA). You may have noticed that there are only four different nucleotides in DNA and in RNA, yet there are twenty-one different amino acids in proteins. The genetic code is conferred by the fact that sequences of three consecutive nucleotides (e.g., TCG, or ATT), called codons, represent a signal for a specific amino acid. Since there are four nucleotides in three possible positions (first, second, or third) there are sixty-four unique combinations of bases, more than enough to code for the twenty-one amino acids, as well as start and stop codons. Indeed, there is some redundancy in the genetic code such that most amino acids have more than one triplet codon.

When a gene is transcribed into an mRNA molecule, portions of the gene are spliced out of the sequence, such that the mature mRNA molecule is much shorter than the sequence of the gene (Figure 7.2). Most genes contain noncoding DNA interspersed between segments of coding DNA. The coding DNA sequences are referred to as exons, and the interspersed noncoding DNA segments are called introns. All of the DNA sequence is initially transcribed into RNA, but enzymes that recognize splice junctions (specific nucleotide sequences at the boundary between an intron and an exon) cut out the noncoding DNA and reassemble the parts into mature mRNA that contains only the complementary sequence of coding DNA from the gene (plus a little bit of noncoding RNA at the beginning and end of the mRNA). Metabolic machinery in the cell then utilizes the triplet codon sequence information in the mature mRNA molecule to assemble amino acids in exactly the correct order. This process is referred to as translation (Figure 7.2). It follows that a small difference from the reference DNA sequence in a particular gene can result in a different protein being formed by that gene.

Types of Genetic Variability

Differences in single nucleotides in the same position of the same gene are the most common type of genetic variability and are referred to as single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs). It is estimated that there are approximately 3 million SNP differences between any two individuals' genomes. In other words, any two people's genomes are roughly 99.9% identical. But variability is not randomly distributed across the genome. Genes that code for critically important functions have very few SNP differences, and are considered to be highly conserved. Most of the SNP variability in the human genome is scattered throughout the large part of the genome that is not part of a gene (intergenic regions), or located in noncoding (intronic) sequences within genes. In fact only about 5% of the 3 billion nucleotides in the human genome are actually in exons (the coding parts of genes), and even then, not all changes in nucleotide sequences within an exon actually change the protein. When there is a change in the nucleotide sequence but the different sequence does not result in a different amino acid (recall that there are usually two or three different codons for the same amino acid), that change is referred to as a synonymous cSNP. The “c” stands for coding, recognizing that most of the DNA sequence in the genome does not even code for proteins. If a SNP in an exon of a particular gene results in a change in the triplet codon for a particular amino acid, resulting in a changed protein, the cSNP is referred to as a non-synonymous cSNP. A substantial amount of the remaining 95% of the genome still provides important information, such as the switching mechanism that determines when genes are or are not expressed, as well as coding for RNA genes, a relatively newly discovered way in which the cell controls its own growth. Even certain intronic sequences have been shown to have a functional role in partially determining the level of expression of a gene or the stability of the mRNA that is formed from the gene.

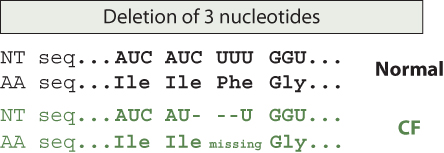

Although SNPs are by far the most common type of genetic variability in the human genome, many other types of differences exist. For example, there can be small (a few nucleotides) or even large (hundreds or thousands of nucleotides) insertions or deletions (so-called indels) in genes. Depending on where the indel occurs, it may have no effect or a little effect, or it may completely eliminate the function of a gene. For example, the genetic disease known as cystic fibrosis can result from a simple three base pair deletion across codons in a gene that codes for a protein that helps to regulate chloride ion flux across cell membranes (Figure 7.3). Because of the three-nucleotide deletion, the protein from the defective gene is missing one amino acid, and that in turn makes the protein ineffective. This is an example of a disease gene. Genetic variants that directly cause a disease are rare (generally occurring in less than 1% of the population), and thus such variants are usually referred to as mutations, rather than polymorphisms.

Figure 7.3 The Cystic Fibrosis Mutation

Note: NT = nucleotide, AA = amino acid.

This figure shows the mRNA sequence for a protein that gives rise to cystic fibrosis, when mutated a certain way (there are other mutations that can also give rise to cystic fibrosis). In this example, three nucleotides (CUU) in the disease gene are deleted, resulting in three missing nucleotides in the corresponding mRNA. This deletion results in one missing amino acid in the protein, an amino acid critical to the protein's function. It is this loss of function that gives rise to the disease characteristics.

Another form of genetic variability occurs when an entire gene is either missing (deletion polymorphism) or occurs more than once in the same genome (gene duplication). One of the most widely studied genetic variants in the human genome is the human glutathione S-transferase M1 (GSTM1) polymorphism, in which about 50% of the human population is homozygous null, meaning that the gene is completely absent from their genome (Text Box 7.1). The form of genetic variability in which someone has inherited multiple copies of the same gene is referred to as copy number variation (CNV). CNVs are actually quite common in the human genome, amounting to an estimated 13% of human genomic DNA, and accounting for about 0.4% of the variability between any two genomes. In rare circumstances, such as with Down's syndrome (Trisomy 21), an entire chromosome can exist with three copies (triploid), instead of the normal two copies (diploid).

How Gene Expression Is Regulated

Transcription Factors and Promoter Regions of Genes

While the structure of the human genome is elegant in its design, equally remarkable are the processes that determine when a gene is expressed in a given cell and how much of it is expressed. As noted previously, every cell has the entire genome but only a small part of it is used to determine the phenotype of a cell, tissue, or individual. What specifically signals a gene to begin the process of transcription, and then translation? Much of this is determined by specific sequences of DNA in the 5′-flanking region of a gene, sometimes called the promoter (or regulatory) region (Figure 7.2). Located at the very “front end” of a gene, these switching signals are represented by unique DNA sequences, from five to over twenty nucleotides long, that provide binding sites for specific proteins that uniquely recognize only that sequence of DNA. By binding to the DNA sequence, these proteins, called transcription factors, initiate the process of transcription. Generally the transcription factor proteins do not act alone but manage to recruit other critical proteins in the process, such that it is actually a complex of proteins that bind to the transcription factor binding site in DNA. In some instances, transcription factor proteins need a small molecule to bind to the protein before they can recruit other proteins, move to the nucleus of the cell, and bind to the binding site on a gene. Such proteins are called ligand-activated nuclear transcription factors. A good example of this is hormonal signaling by such molecules as estrogen, testosterone, and thyroid hormone. Estrogen—either produced normally in the body (endogenous) or from an exogenous synthetic estrogen (such as a birth control pill)—is recognized by a specific protein called the estrogen receptor. When the ligand (estrogen) binds to its receptor, the complex moves to the nucleus, and binds to estrogen receptor binding sites on certain genes, which are then turned on to express the gene (make the specific protein). Thus it is transcriptional activation via estrogen of a whole host of genes involved in the female reproductive function that provides the phenotype associated with endogenous production of estrogen. Likewise, some chemicals in the environment, called endocrine disruptors, can also affect estrogen signaling, either by mimicking estrogen and activating the estrogen receptor (an estrogen receptor agonist) or by blocking estrogen from binding to the receptor (an estrogen receptor antagonist). (See Text Box 6.4, in Chapter 6.)

Epigenetic Regulation of Gene Expression

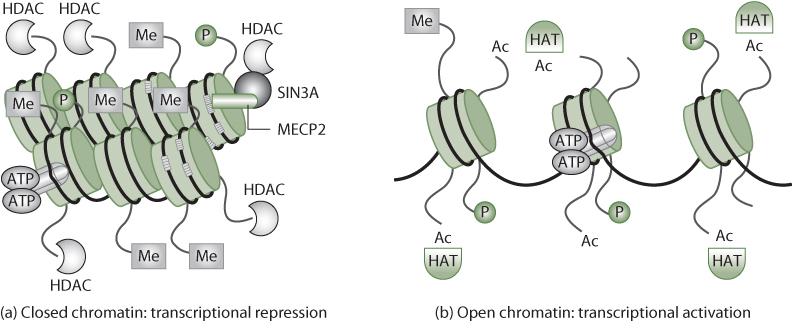

Although ligand-activated transcription factors represent an important pathway for regulation of gene transcription, there are many other cellular processes involved in regulating gene expression. An exciting new area of discovery is epigenetic regulation of gene expression (Figure 7.4). It was discovered many decades ago that some of the nucleotides in regulatory regions of genes could exist in two forms—with a methyl group attached to certain bases in certain positions or in a normal, unmethylated state. It is now recognized that early in life, during embryonic and fetal development, and throughout life, when cells are undergoing replication, regulatory regions of genes across the entire genome manifest differing states of DNA methylation. In general, genes with more methylated bases in the regulatory region (hypermethylation) are underexpressed (mostly switched off), whereas genes with fewer methylated bases in the regulatory region (hypomethylation) tend to be overexpressed (switched on). Modulation of gene expression via changes in DNA methylation is one form of epigenetic regulation of genes.

Figure 7.4 Chromatin Dynamics in Response to Epigenetic Modification

Source: Johnstone, 2002.

In this figure, methylation induces a closed chromatin state, while removal of methyl groups (Me) and addition of acetyl (Ac) groups results in an opened chromatin state, allowing easier access for transcriptional machinery. Also involved in nucleosome structure are phosphorylation (P), the enzymes histone acetyltransferases (HATs) and histone deacetylases (HDACs), and methyl-binding proteins (MECP2).

The elegant switching on and off of genes during embryonic and fetal development is what allows the amazing development of a fertilized egg into a healthy baby. And complex regulation of gene expression through methylation of DNA continues to occur throughout early development and into adulthood. Obviously, interference with or perturbations of DNA methylation could have grave consequences for a developing embryo or for the successful growth and development of a young child into a healthy adult. Changes in DNA methylation are a common characteristic of many neoplasms (benign and cancerous tumors). Changes in gene expression, because of altered epigenetic regulation, and/or the accumulation of mutations in DNA in somatic cells in the body are what cause a normal stem cell to veer into cancerous growth.

Although methylation is one of the most important and best understood mechanisms of epigenetic regulation of gene expression, there are other epigenetic modes of alteration of gene expression. For example, a group of proteins known as histone deacetylases (HDACs) have the unique function of changing how histone proteins are folded. Histones facilitate the proper winding of DNA into chromosomes in the nucleus. In order for a gene to be expressed, it has to be unwound from the histones to allow DNA and RNA synthesis machinery to read the DNA sequence (transcription and translation). The addition of an acetyl group (two carbons and one oxygen) to a histone will affect its ability to wind and unwind DNA and thereby affect the efficiency of transcription. Thus alterations in histone acetylation and deacetylation, like alterations in DNA methylation and demethylation, can affect transcriptional efficiency of a gene.

Lastly, epigenetic regulation of gene expression can also be determined in part by the binding of a relatively newly discovered class of RNA, called microRNA (miRNA), to the 3′-terminal ends of mRNA molecules. These miRNAs are derived from non-protein-coding genes (so-called RNA genes). Once fully formed, miRNAs are twenty-one to twenty-three nucleotides long, and function by recognizing specific sequences in the 3′ end of a mature mRNA molecule (Figure 7.2). The miRNA binds to the mRNA where it inhibits the efficient translation of that mRNA and/or targets the mRNA for degradation, such that the level of gene expression is decreased.

As described earlier, changes in DNA—mutations—have a role in many diseases. However, many (perhaps most) environmental diseases are not the result of mutations; instead, the epigenetic mechanisms just described are responsible. The epigenome responds dynamically to cues from the environment, including the drugs you take, the air you breathe, the food you eat, how stressed you are, and what toxicants you are exposed to.

To get a better sense of the epigenetic regulation of gene expression, consider the example of identical twins. Although they are genetically identical (they are from the same embryo), they become phenotypically divergent; they look different from one another as they age and they act differently. This is the result of differences in diet, exercise, lifestyle, and so forth, which change the methylation and acetylation patterns in their epigenomes. The more we learn about epigenetics, the more apparent it has become that epigenetic changes can influence health, not only of directly affected people but also of subsequent generations. The choices a person makes in his or her lifetime can affect his or her own epigenome and also that of his or her offspring. This hereditary transmission of environmental information is known as transgenerational epigenetic inheritance.

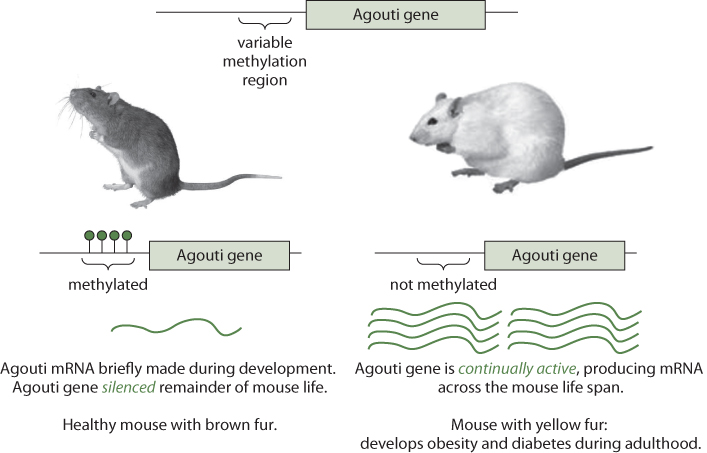

Experiments in mice highlight the important of maternal diet in shaping the epigenome of offspring. For example, all mammals have a gene called the agouti gene. The product of this gene is a 131 amino acid peptide that causes the pigment cells in hair follicles to synthesize a yellow pigment instead of black or brown pigment. But the same agouti peptide also binds to certain receptors in the brain, causing changes in metabolism that result in obesity. Thus, when a mouse's agouti gene is demethylated, its coat is yellow, and the mouse is obese and prone to diabetes and cancer. When the agouti gene is methylated (as it is in normal mice), the coat color is brown and these mice have a low obesity risk. Fat yellow mice and skinny brown mice are genetically identical (Figure 7.5). The fat yellow mice have an altered phenotype because of epigenetic modifications that simultaneously change hair color and fat metabolism (Duhl, Vrieling, Miller, Wolff, & Barsh, 1994). When researchers fed pregnant yellow mice (those that have the demethylated agouti gene) a diet rich in methyl group precursors, such as Vitamin B12 or betaine, most of the pups were brown and stayed healthy for life. The results of this experiment show that the environment in the womb influences adult health, and support the fetal origins of adult disease hypothesis, which states that early developmental exposures involve epigenetic modifications that influence disease susceptibility as an adult.

Figure 7.5 Schematic of the Agouti Gene and How Its Methylation Status Affects Phenotype in Mice

Source: Hudson Alpha Institute for Biotechnology, 2009.

Chemicals and additives that enter our bodies can also affect the epigenome. Bisphenol A (BPA), a synthetic chemical with endocrine-disrupting properties, is a plasticizer previously used in many consumer products, including water bottles and tin cans (as described in Tox Box 6.1 in Chapter 6). But in recent years its use has been phased out following studies suggesting health hazards, especially in infants and children. Perhaps the most striking evidence for BPA's toxicity came from a study of the agouti gene in lab mice (Dolinoy, Huang, & Jirtle, 2007). When pregnant yellow mothers were fed BPA, more yellow, unhealthy babies were born than normal. Exposure to BPA during early development had resulted in decreased methylation of the agouti gene. However, when BPA-exposed, pregnant yellow mice were fed food supplemented with methyl donors (e.g., vitamin B12 and folic acid), the offspring were predominantly brown (methylated agouti gene). Thus the maternal nutrient supplementation had counteracted the negative effects of exposure. Taken together, these studies suggest that our health is not only determined by what we eat and to what we are exposed but also by what our parents ate and perhaps their environmental exposures when they were young.

Omics Technologies

The suffix -omics first came into widespread use in association with genetics. The complete set of genes contained in an organism's DNA was referred to as the genome, so the study of the genome was called genomics. Following suit has been a host of similar terms used to describe the study of particular aspects of genomics. For example, the entire complement of mRNA molecules (gene transcripts) in a given cell is referred to as that cell's transcriptome, and the study of the entire set of transcripts in a particular cell or tissue at a particular point in time is referred to as transcriptomics. Since most transcripts (mRNA) in a cell can be converted to proteins, the entire population of proteins within a cell or tissue is referred to as the proteome, and the study of the proteome is proteomics. Likewise, all parts of a cell that are involved in the cell's complex metabolism, such as the substrates, cofactors, and products of each of the thousands of enzymatic reactions carried out by the proteome, are referred to as the metabolome, and the study of metabolomes is thus metabolomics. Not surprisingly, similar terminologies have arisen to describe the study of the global process by which epigenetic factors influence gene expression—epigenomics. One subset of the epigenome is the global pattern of methylation of nucleotides throughout an entire genome, and it is referred to as the methylome. New tools and technologies in molecular biology now make it possible to acquire not only the entire sequence of someone's genome but also his or her transcriptome, proteome, metabolome, and methylome. However, it is important to note that the genome of an individual is identical in every cell, whereas the transcriptome, proteome, metabolome, and methylome are unique to each tissue, and even to the time the sample from that tissue was collected! Thus, although genomes are highly stable across tissues and time, all of the other omics outputs are tissue and time specific. Given that there are about 24,000 genes, probably more than 100,000 different proteins, and literally millions of potential measurement values across tissues and time in a single individual, managing such a huge amount of information is very challenging and requires sophisticated mathematical and computational approaches.

Fortunately, new computing approaches and hardware, software programs, and robust statistical analyses are continuously being developed and improved to collect, organize, and analyze DNA and protein sequences, transcriptomes, metabolomes, and other sources of large data generated by modern biological and health sciences research. This growing field, known as bioinformatics, is an essential component of all omics technologies. One of the biggest challenges scientists face when confronted with literally hundreds of thousands to millions of comparisons is the so-called false discovery rate. Recall the familiar statistical concept of comparing two variables to determine whether one is significantly different from the other, often using simple tests such as the t-test. One of the first decisions in applying any such test is to decide on a level of significance. For example, a common choice of p value is 0.05; when p < .05, there is less than a 5% probability that an observed difference between two values occurred by chance, suggesting that some factor—perhaps the independent variable under study—is truly associated with the difference. However, accepting this 5% threshold implies that in 5% of observations, what seems statistically significant is in fact a chance occurrence (assuming that the data are normally distributed). Now imagine doing 1 million different comparisons, having set the p value at 0.05. This means that 50,000 of the comparisons would show statistically significant differences just as a result of random variation rather than of true, functional differences. This is referred to as the multiple comparisons problem, and the erroneous positive associates are called false discoveries. Thus statistical approaches that utilize far more rigorous comparison thresholds than p < 0.05 are required to identify changes that are truly significant. For this reason, modern biostatistical analyses increasingly include a bioinformatics perspective, to help researchers analyze and interpret the huge amounts of data that are becoming commonplace in molecular biology laboratories around the world. This is especially important in the study of gene-environment interactions, where many comparisons of different gene polymorphisms with respect to environmental factors can lead to spurious associations that arise just by chance (false discoveries).

Approaches for Identifying Gene-Environment Interactions

The early concepts that genes and environment could somehow interact to produce disease came from pioneering studies over 100 years ago on the origins of metabolic diseases. Sir Archibald Garrod (1857–1936), a distinguished English physician, was the first to describe familial “inborn errors of metabolism,” including the conditions known as alkaptonuria and albinism. Although he did not use the term genetics, Garrod clearly described the concept of individual susceptibility, and envisioned the role of genetic factors in diseases: “In every case of every malady there are two sets of factors at work in the formation of the morbid picture, namely internal or constitutional factors, inherent in the sufferer and usually inherited from his forebearers and external ones which fire the train” (Omenn & Motulsky, 2006). One of Garrod's coworkers, William Bateson (1861–1926), coined the term genetics, to describe the occurrence of these metabolic disorders in families (parents and siblings). Bateson noted that these metabolic diseases often occurred in marriages among first cousins whose parents did not display the disease, an occurrence that we now know is consistent with a recessive Mendelian trait.

In the early years of genetic discovery, research focused solely on the effect of an individual organism's genes or genome on that organism's health. However, variations in single genes that cause disease (Mendelian disorders) are quite rare, and thus relatively few individuals benefit from identification of these genes. Common afflictions such as type 2 diabetes and obesity, which have great public health significance, are far too complex to be explained by the action of a variant in a single gene. Instead, such conditions result from gene-environment interactions. For the purposes of this discussion, environment refers to anything outside the body that can affect one's health. Such a broad definition is necessary, given that virtually any type of exposure (e.g., climate, food, drugs, radiation, chemicals) can be associated with a health outcome in an individual or population, possibly resulting in a diseased state. Elucidating the interactions between genes and also between genes and the environment in the context of multifactorial diseases such as obesity, is extremely important in reducing the burden they impose on society.

There is a distinction between an environmental response gene and a disease gene. An environmental response gene dictates a person's response to certain environmental exposures, but without such an exposure this gene generally has no health consequence. One example is a polymorphism in a gene called N-acetyltransferase 2 (NAT2), which is discussed later in this chapter. (Note also that an environmental response gene may be responsive to many different exposures if that gene encodes for a protein in a common metabolic pathway.) Conversely, a disease gene is one that causes a disease irrespective of environmental cues. Cystic fibrosis, a terribly debilitating disease, is caused by mutations in the CFTR gene, which encodes for the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator protein. Many different mutations within the CFTR gene may result in this disease, most resulting in an amino acid substitution or deletion (see Figure 7.3) that causes the CFTR protein to malfunction or be degraded. Many other disorders are caused by heritable disease genes, including Huntington's disease, Duchenne muscular dystrophy, and sickle-cell anemia, as well as certain types of Parkinson's disease. However, very rarely are diseases the result of mutations in a single gene; more often disease results from the interactions of multiple genes, all or some of which may have uncommon genetic variants. A final point to keep in mind is that environmental exposures can affect the severity or progression of a disease even when the disease itself is not caused by an exposure per se. For example, cystic fibrosis is not caused by exposure to smoke or airborne pollutants but is certainly aggravated by these exposures.

Although significant strides have been made in understanding the genetic bases of disease, this knowledge remains incomplete. As we have already discussed, many factors can influence disease and the risk of disease; however, there are now specific types of studies that aim to parse the genetic components underlying disease. They are termed genetic association studies. Genetic association is the co-occurrence, more frequently than would occur by chance, of a genetic characteristic and some other trait(s). There are two main approaches used in genetic association studies. The first, the candidate gene approach, is hypothesis driven, building on a detailed understanding of biochemical pathways. Given a gene's known role in a pathway important to a disease of interest, scientists can advance an educated guess as to what might occur if that gene's functionality were altered in some way. Researchers then sequence the gene of interest in patients with a particular disease, and determine whether a mutation is more common among them than among people without that disease. An example is the LMNA gene responsible for Hutchinson-Gilford progeria syndrome (Eriksson et al., 2003).

Technical advances have allowed for a newer, so-called agnostic approach to genetic association studies, one that is much broader in scope. Instead of focusing on one or a few genes, a genome-wide association study (GWAS) scans a wide range of genes, seeking associations between particular genes and traits of interest. Proponents of this approach consider it less inherently biased than candidate gene studies. However, GWAS require much larger sample sizes and more complex statistical analyses, and due to the sheer amount of data, such studies may result in spurious positive results. Nonetheless, GWAS studies are particularly relevant to environmental health because they can integrate environmental exposure data with genetic analysis. For example, a GWAS might compare a group of diseased factory workers with nondiseased workers from the same factory, genotyping them all for common SNPs, and stratifying them according to their workplace exposures. Sophisticated statistical analysis can then be employed to reveal genes or GxE interactions that may be associated with the disease outcome. This powerful technique can be harnessed together with candidate gene approaches to understand more completely the genetic underpinnings of disease.

Examples of Gene-Environment Interactions in the Real World

Drug Responses

Much of what we know today about GxE interactions stems from early discoveries related to individual, or in some instance racial/ethnic, differences in response to drugs given to treat a disease. One of the first observations of a clinically relevant drug response that differed between racial groups occurred during World War II. When U.S. troops were fighting in parts of the world where malaria was common, it was noticed that some but not all soldiers developed a blood disease called hemolytic anemia following treatment with the antimalarial drug primaquine. Moreover, nearly all those who developed this adverse effect from the drug were African American (Earle, Bigelow, Zubrod, & Kane, 1948), which strongly suggested that some genetic difference conferred susceptibility. Today we know that this response is due to a variant in a gene for the protein, glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PDH), and that the variant allele is much more common in people of African and Mediterranean ancestry than it is in Caucasians.

One of the most dramatic early examples of a drug-gene interaction involves a drug that is widely used to cause local muscle paralysis during surgery. This drug, succinylcholine, is a very effective inhibitor of the neurotransmitter acetylcholine, released at the neuromuscular junction. When the brain signals a muscle fiber to contract, that electrical signal is converted to a chemical signal, the neurotransmitter acetylcholine, which binds to a receptor in the muscle fiber, causing it to contract. Succinylcholine is an inhibitor of the acetylcholine receptor, thereby blocking the stimulation of the muscle fiber. Normally succinylcholine is rapidly broken down in the bloodstream by an enzyme called pseudocholinesterase (also called butyrylcholinesterase). Because it is so quickly broken down, physicians normally just drip the drug into an IV to maintain paralysis. Once the surgery is complete, the drip is stopped, and the patient quickly regains muscle function as the drug is eliminated from the body. As the name suggests, pseudocholinesterase doesn't participate in the normal breakdown of acetylcholine, so there are no serious physiological consequences if the enzyme is deficient. Indeed, there is a genetic polymorphism that is present in a small percentage of the population that results in a pseudocholinesterase enzyme with little or no activity—ordinarily a harmless trait, even in people who are homozygous for the defective enzyme. But if these people receive a normal therapeutic dose of succinylcholine, they remain paralyzed for hours or even days, because it is not promptly broken down and continues to block excitation of muscle fibers (Omenn & Motulsky, 2006).

The term pharmacogenetics was first used in 1959, by Vogel, to describe such phenomena. Other investigators utilized studies comparing drug responses in identical and fraternal twin pairs. Such studies revealed that identical twins had much more similar plasma levels and elimination rates of common drugs than did fraternal twins (Omenn & Motulsky, 2006). However, it was also discovered that some drugs have a bimodal or trimodal distribution of pharmacological effects, toxicity, and plasma levels across populations, suggesting a simple pattern of Mendelian inheritance (Omenn & Motulsky, 2006). Numerous drugs have such profiles, indicating important single gene differences in how these drugs are metabolized.

Dietary, Occupational, and Environmental Exposures

Medications provide revealing examples of GxE interactions, but the same principles can be seen in dietary, workplace, and general environmental exposures as well. This section offers three more examples in which multiple genes are involved in modulating risk: one involving alcohol, a dietary exposure; a second involving beryllium, a workplace exposure, and the third involving exposure to pesticides, which can occur as either an occupational or a nonoccupational exposure. Additional examples appear in Tox Box 7.1, on benzene, and in Text Box 7.2, on mercury. These examples illustrate the complexity of many GxE interactions.

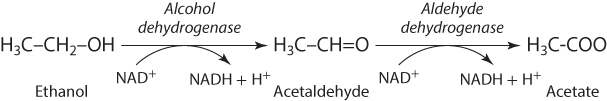

Alcohol

Drinking excessive amounts of alcohol can lead over time to multiple pathologies in the liver, including cirrhosis, or fibrotic hardening of the liver, and liver cancer. There are also acute effects that can be modulated by genotype. As with many chemical exposures, these effects are related primarily to biotransformation of the parent compound. In this metabolic pathway, ethanol is converted to acetaldehyde by an enzyme called alcohol dehydrogenase (ADH), which is most active in the liver and stomach, and then to acetate by a second enzyme, aldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH) (see Figure 7.6).

Figure 7.6 Primary Biotransformation Pathway for Alcohol

Although acetate is relatively nontoxic, acetaldehyde is toxic, and it is therefore important to keep circulating levels of acetaldehyde low. A relatively common polymorphism, seen primarily in Asian populations, exists in the ALDH2 gene. This variant, known as ALDH2*2, results in reduced function of the ALDH2 enzyme, leading to a buildup of acetaldehyde in the blood following consumption of alcohol, and causing severe flushing and very unpleasant “hangover-like” symptoms (Crabb, Matsumoto, Chang, & You, 2004). For people harboring the ALDH2*2 variant, even very small amounts of alcohol can result in a severe reaction. Interestingly, based on an understanding of this mechanism of action, a drug called disulfiram, or Antabuse, that inhibits the ALDH2 enzyme was developed for the treatment of alcoholism and remains an effective approach. People who take Antabuse know that they will become very ill if they drink alcohol, so it provides a strong and usually effective means of discouraging alcohol consumption.

Chronic Beryllium Disease

A unique example of workplace exposure and risk of disease involves beryllium, the fourth element in the periodic table. Beryllium is most commonly used to make metal alloys that are exceptionally strong, light, and flexible and are used in settings such as the aerospace industry. Although beryllium is present in microgram quantities in our bodies, it is highly toxic. Like many other metals, beryllium's toxicity is related to its ability to displace metal ions (in this case, primarily magnesium) in enzymes, thereby impairing their function. Not only is beryllium classified as a Group I carcinogen by IARC but beryllium poisoning can also lead to debilitating, incurable lung illnesses, including acute beryllium disease and chronic berylliosis. While dermal and oral exposure can occur, the most common route of exposure is inhalation, especially among workers manufacturing beryllium alloy–containing products, and the pathology related to beryllium exposures manifests primarily in the lungs.

Chronic berylliosis is notable for a few reasons. First, workers who develop berylliosis may not display symptoms until many years after exposure. This is because the immune response elicited by beryllium exposure first requires sensitization, or priming, of the immune system. A person who is sensitized to beryllium may, when reexposed, mount an immune response that recognizes beryllium as a threat and activates a unique group of scavenging cells called macrophages. This is usually a helpful process, but in people who develop berylliosis, the macrophages begin to cluster after repeated exposures, forming granulomas in the lung that eventually impair lung function.

Interestingly, sensitivity to beryllium seems to be governed primarily by variation in a single gene, HLA-DPB1, which encodes human leukocyte antigen class II histocompatibility antigen, DP(W2) beta chain, a cell surface receptor responsible for eliciting a particular immune response. The SNP called HLA-DBP1*0201 results in an amino acid substitution of a glutamate instead of the normal lysine at amino acid position 69. Although this variant is quite common, present in about 33% of the general population, only about 5% of beryllium-exposed workers develop chronic berylliosis. Thus the variant is not necessarily a specific predictor of berylliosis risk (in epidemiological terms, the positive predictive value is low). However, between 75% and 97% of beryllium-exposed workers who develop chronic berylliosis harbor the Glu69 variant, compared to only 30% to 45% of workers who do not develop berylliosis (Silver & Sharp, 2006). Thus the negative predictive value is high. These facts raise fascinating ethical, social, and legal issues, which are explored in the discussion questions at the end of this chapter.

Pesticides

One of the most complicated examples of a GxE interaction involves organophosphate (OP) pesticides and the serum enzyme paraoxonase 1 (PON1). As described in Tox Box 18.1, OP compounds elicit nearly all of their toxic effects by inhibiting the action of acetylcholinesterase (AChE), an enzyme that breaks down the important neurotransmitter acetylcholine. When the action of AChE is blocked, acetylcholine is allowed to continue stimulating neuromuscular junctions. As a result, OP poisoning can result in excessive stimulation of the nervous system, leading to a constellation of symptoms summarized as SLUDGE (salivation, lacrimation, urination, defecation, gastrointestinal movement, and emesis). PON1 hydrolyzes some OP compounds to prevent their toxic effect on AChE, and variations in PON1 can modify these toxic effects.

Two polymorphisms in PON1 are usually considered: PON1 a nonsynonymous cSNP called Gln192 and a non-coding variant called PON1 108C → T. Substituting the wild type arginine at codon 192 for a glutamine increases the catalytic efficiency of PON1, while the PON1 108C → T variant affects the expression of the gene and thus decreases the serum levels of PON1. Only by examining the genotype for both of these alleles can one make an accurate assessment of a person's susceptibility to OP toxicity. Factors other than OP exposure can also modulate PON1 activity, including alcohol, smoking, certain drugs, diet, and certain physiological and pathological conditions (Costa, Vitalone, Cole, & Furlong, 2005).

These examples illustrate the ways in which genes and environmental exposures interact to affect people's responses to exposures, and they also highlight some of the challenges public health professionals must consider when investigating gene-environment interactions.

Summary

Most of the chronic diseases of greatest public health importance, such as cancers, heart disease, degenerative neurological diseases (e.g., Parkinson's, Alzheimer's), and diabetes and other metabolic disorders, arise from complex interactions between a person's inherited biology (both genetic and epigenetic in origin) and his or her environment. While the genetic and epigenetic deck of cards you are dealt at birth is not readily modifiable, many environmental factors are. Thus there is great interest and value in understanding gene-environment interactions, to permit interventions such as environmental control measures that can reduce disease burden. In this chapter, we have discussed the tools, technologies, and approaches used by public health scientists to tease apart these complex interactions. The wonderful discoveries made possible through advances in genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics and metabolomics—coupled with advances in computational and statistical approaches to managing the massive amounts of data derived from these tools (bioinformatics), and large, novel population-based study designs (e.g., genome-wide association studies, GWAS)—hold great promise. This field will increasingly help to identify modifiable environmental factors that can reduce the incidence of environment-related diseases, and improve both early diagnosis and treatment.

Key Terms

- 5′ flanking region

- Region of DNA adjacent to the 5′ region, or beginning of the gene, in contrast to the 3′ region, which is at the end of a gene.

- adenine

- A nitrogenous purine base (abbreviated “A”) found in DNA and RNA; pairs with thymine in DNA and uracil in RNA.

- aflatoxin B1 (AFB1)

- Mycotoxin produced by the mold Aspergillus flavus, which grows commonly on corn and peanuts. This B1 form is among the most potent liver carcinogens yet discovered.

- agonist

- A chemical that binds and activates a receptor, eliciting a biochemical response.

- allele

- One of a number of alternative forms of a gene or DNA sequence that can occupy a genetic locus on a chromosome. Different alleles produce variation in inherited characteristics, and one form of an allele may be expressed more than another form in an individual (dominant versus recessive alleles).

- amino acid

- Organic molecule containing both an amine (-NH2) and carboxyl (-COOH) group. There are twenty-one amino acids that link together to form peptides (fewer than ≈50 amino acids) and proteins (more than ≈50 amino acids).

- antagonist

- Chemical that blocks agonist-mediated responses rather than eliciting a biological response itself upon binding to a receptor.

- autosome

- Any chromosome other than a sex chromosome. Humans have twenty-two pairs of autosomes and one pair of sex chromosomes (XX in females and YY in males).

- berylliosis

- A lung disease resulting from exposure to beryllium or beryllium alloys; it involves an immune response and may persist irrespective of exposure level.

- bioinformatics

- A field that uses computer science, mathematics, and statistics to collect, organize, and analyze complex biological data.

- candidate gene

- A gene located on a chromosome region suspected of being involved in a disease and producing a protein that could contribute to the development of the disease in question.

- chromosome

- A structure composed of long, threadlike packages of DNA and associated proteins that carries all the information of an organism.

- codon

- A three-base sequence in DNA that is transcribed into mRNA and specifies a single amino acid to be added into a polypeptide chain or causes termination of translation.

- copy number variation (CNV)

- Differences between individuals in the number of copies of a particular gene. Although every gene in a genome typically has two alleles, it is not unusual for multiple copies of one or the other allele to be present in the gene region.

- cytosine

- A nitrogenous pyrimidine base (abbreviated “C”) found in DNA and RNA; pairs with guanine in DNA and RNA.

- deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA)

- The chemical in the cell nucleus that carries genetic instructions for an organism's structure and function.

- deoxyribose

- Pentose (5-carbon) sugar present in a nucleotide subunit of DNA, with only one hydroxyl group on the sugar (in contrast to ribose, which has two hydroxyl groups on the pentose sugar).

- diploid

- Containing two sets of homologous chromosomes (i.e., a “double” genome) and hence two copies of each gene or genetic locus. The diploid number in humans is 46.

- disease gene

- A gene or gene variant that results in a disease state, irrespective of environmental cues.

- double helix

- The structural arrangement of DNA, resembling a spiraling ladder and created by the specific base pairing of individual nucleotides through hydrogen bonding.

- endocrine disruptor

- An exogenous agent that interferes with the production, release, transport, metabolism, binding, action, or elimination of natural hormones, such as estrogen, androgens, and the thyroid hormone.

- endogenous

- Originating within an organism.

- environmental factors

- Abiotic or biotic factors that influence living organisms.

- environmental response gene

- A gene that dictates a person's response to certain environmental exposures but that without such an exposure generally does not confer injury or advantage.

- epigenetic

- Involving heritable, phenotypic changes in gene expression that do not involve changes in gene sequence; often these changes are controlled by methylation of cytosine bases in DNA and/or modification of histone proteins.

- epigenome

- All the chemical modifications (e.g., methylation, histone acetylation) accrued to the entirety of one's genome, other than changes in the core composition of DNA (mutations).

- epigenomics

- The study of heritable, phenotypic changes in gene expression that do not involve changes in gene sequence.

- exogenous

- Originating outside an organism.

- exon

- Segment of a gene consisting of a sequence of nucleotides that will be represented in mRNA. In protein-coding genes, exons encode the amino acids in the protein. Exons are usually adjacent to introns.

- false discovery rate

- The expected percentage of false predictions based on chance alone in a set of predictions.

- fetal origins of adult disease

- The concept that events during early development (e.g., malnutrition) have a profound impact on a person's risk for development of certain chronic diseases as an adult. Also referred to as the Barker hypothesis.

- gene

- The basic unit of heredity. A chromosomal segment that carries information for a discrete hereditary characteristic, usually corresponding to an RNA sequence or protein.

- gene-environment interaction

- Differential effect of a particular environmental exposure on disease risk in people with different genotypes. Ecogenetics is the study of genetic determinants that define susceptibility to environmentally influenced adverse health effects.

- genetic association

- The co-occurrence, more often than can be explained by chance, of two or more traits in a population of individuals and where at least one trait is known to be genetic.

- genetic code

- The complete set of triplet codons in DNA that signals for protein production, including start and stop codons, and multiple triplet codons specific for each of the 21 amino acids used to construct peptides and proteins from mRNA.

- genome

- A single complete set of genetic information (i.e., the genes plus all the noncoding information) contained in an organism's or cell's DNA.

- genome-wide association study (GWAS)

- Investigation of many common genetic variants in different individuals to determine whether any genetic variant is associated with a particular trait or phenotype.

- genomics

- The comprehensive study of whole sets of genes and their interactions, rather than single genes.

- genotype

- The allelic constitution, which does not show directly as outward characteristics. The genotype is dictated by the specific nucleotide sequences within genes.

- guanine

- A nitrogenous pyrimidine base (abbreviated “G”) found in DNA and RNA; pairs with cytosine in DNA and RNA.

- Hepatitis B virus (HBV)

- A virus that primarily manifests its effects in the liver, resulting in chronic hepatitis. HBV is a major risk factor for hepatocellular carcinoma.

- hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC)

- A type of liver cancer arising from the epithelium, which can result from a number of preventable factors, such as Hepatitis B and C infection, chronic alcohol consumption, aflatoxin ingestion, and diabetes.

- histones

- Small, positively charged proteins that fold to form nucleosome cores around which DNA is wrapped in chromosomes. Histones can be important in epigenetic regulation (see epigenetic).

- histone deacetylase (HDAC)

- Enzyme that removes acetyl groups from core histones.

- homozygous

- Possessing two identical forms of a particular gene (allele), one inherited from each parent.

- indel

- A region in a gene where a small segment of nucleotides (from two to several hundred) has been inserted in or deleted from the normal sequence of the gene.

- intergenic region

- A length of DNA sequence located between defined genes.

- intron

- A noncoding region of a gene that is transcribed into an RNA molecule but then excised by RNA splicing. Although often considered to have no biological function, introns may encode other regulatory RNAs, such as miRNAs, or include recognition motifs that control transcription and/or RNA stability.

- ligand-activated nuclear transcription factor

- Transcription factor activated by the binding of a specific substrate, which may induce a conformational change in the transcription factor or facilitate its transit into the nucleus.

- locus

- In genetics, the place on a gene where a specific gene is located.

- messenger RNA (mRNA)

- Template for protein synthesis that binds to ribosomes. The sequence of a strand of mRNA is complementary to the cognate sequence of DNA from which it is transcribed.

- metabolome

- The complete set of small molecules in a biological sample; they reflect biochemical processes occurring within the cells or tissue of interest. The metabolome may be altered in response to an environmental exposure or disease state.

- metabolomics

- The systematic study of metabolites or suites of metabolites within a given cell or tissue.

- methylation

- Addition of methyl (CH3-) groups to DNA. Methylation of certain cytosine bases in a gene's DNA often results in silencing that gene's expression. Chemical perturbations and certain disease states may result in or from hypo- and hypermethylated genes.

- methylome

- Set of methylation modifications to DNA in an organism's genome.

- microRNA (miRNA)

- Short (21 to 23 nucleotides) RNA molecule encoded by a gene that can regulate gene expression through complementary base-pairing with mRNA.

- multiple comparisons problem

- The problem inherent in a data analysis with a large enough number of comparisons to raise the risk of false positive findings.

- mutation

- A permanent structural alteration in DNA. In most cases, mutations either have no effect or cause harm, but they can occasionally confer an advantage to the organism. The concept of natural selection is based on the theory that random mutations can give rise to beneficial changes that provide a selection advantage over other organisms that do not have the mutation.

- non-synonymous cSNP

- A SNP in the coding region of a gene (e.g., in an exon) that produces a change in the translated sequence, resulting in an altered amino acid sequence being translated from the mRNA transcript of the gene of interest.

- nucleotide

- A structural component of DNA and RNA that is composed of a 5-carbon sugar (ribose in RNA and deoxyribose in DNA), at least one phosphate group, and a nitrogenous base.

- phenotype

- The observable characteristics, including physical appearance and behavior, of a cell or organism. Phenotype can be defined at the level of the organism or at discrete levels of function, such as at the enzyme activity level.

- polymorphism

- A change in the nucleotide sequence of a specific region of DNA in one DNA sample when compared to the sequence in many samples. Polymorphism can exist in many different forms, including gene deletions, gene duplications, indels, or single nucleotide polymorphisms.

- promoter

- Nucleotide sequence in DNA to which RNA polymerase binds to begin transcription; most often upstream of the transcriptional initiation site.

- proteome

- The entirety of proteins expressed in a cell, tissue, or organism at any given moment in time.

- proteomics

- Study of all the proteins produced by a cell, tissue, or organism. Proteomics often investigates changes in the proteome caused by changes in the environment or by extracellular signals.

- receptor

- Any protein that binds to a specific signaling molecule (ligand) and initiates a cellular response; receptors may be present on the cell surface or within the cell.

- ribonucleic acid (RNA)

- A polymer formed from covalently linked ribonucleotide monomers. In RNA, uracil is substituted for thymine in the genetic code.

- single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP)

- A SNP arising through a single base pair change in a specific region of DNA compared to the same region in a population of DNA samples. To be classified as a SNP, the allele frequency (variant form) must be present in a population of at least 1% of the alleles; if it occurs at a lower rate, it is considered a rare variant or a mutation.

- splice junctions

- Sites at which introns and exons join and the exons are then ligated following removal of the intronic sequences during transcription.

- splicing

- Linking two RNA exons together while removing the intronic DNA sequence that lies between them.

- synergism

- An instance in which the combined effects of two chemicals are greater than the sum of the effects of each agent alone.

- synonymous cSNP

- A SNP in the coding region of a gene (e.g., in an exon) that results in no change in the translated sequence (cf. non-synonymous SNP).

- thymine

- A nitrogenous purine base (abbreviated “T”) found in DNA. Thymine pairs with adenine in DNA. In RNA, thymine is replaced with uracil.

- transcription

- Copying of one strand of DNA into a complementary RNA sequence by RNA polymerase.

- transcription factor

- Sequence-specific DNA binding protein that binds to gene promoters and other regulatory elements (transcription factor binding sites) and initiates gene-specific transcription.

- transcriptome

- The entire complement of RNA molecules in a given cell.

- transcriptomics

- The study of the transcriptome.

- transgenerational epigenetic inheritance

- The passing of epigenetic alterations to the genome (and associated phenotypic alterations) to subsequent generations. Most, but not all, epigenetic modifications are cleared and reestablished during each generation. Environmental factors may modify the extent of transgenerational epigenetic inheritance.

- translation

- The process by which ribosomes decode an RNA message (mRNA) to synthesize a protein.

- triploid

- Possessing three sets of a particular chromosome or chromosomes. Whole organism triploidy would result in 69 chromosomes. Trisomy 21, in which a third copy of chromosome 21 results in the phenotype described as Down syndrome, is the best known triploid disease.

- uracil

- A nitrogenous purine base (abbreviated “U”) found in RNA. Uracil pairs with adenine in RNA.

- variant (allele)

- An alteration in the normal sequence of a gene. Hundreds of variants may exist for a single gene. Whether the sequence variability is considered the common form (sometimes called wild type) or the variant form (sometimes called mutant) may depend on the reference population, since variant alleles are heritable and will be enriched in populations with many carriers.

Discussion Questions

- Almost all workers who develop chronic berylliosis harbor the Glu69 variant, compared to only 30% of workers who do not develop berylliosis. At least three approaches to the use of genotyping for the Glu69 variant might be considered:

- Employers that use beryllium require all potential employees to be genotyped prior to hiring, and reject applicants based on a positive finding.

- Employers that use beryllium require all potential employees to be genotyped prior to hiring, provide a detailed explanation of the risks involved for Glu69-positive workers, then allow each applicant to decide whether to accept employment, and ask hired workers to sign a waiver taking full responsibility for any adverse outcomes.

-

Employers do not use genetic testing.

Which approach do you favor, and why? How would your answer change if the predictive value of genetic testing were 100%?

- As you read in Text Box 7.2, genetic variants in CPOX and COMT genes can increase susceptibility to mercury (Hg) exposure (e.g., from fish consumption or dental amalgams), especially in boys. However, fish are also a leading dietary source of omega fatty acids, which are important for neurological development. How would you frame this issue for public education, and how would you present possible testing options for children who may be at risk of increased mercury exposure?

References

- Costa, L. G., Vitalone, A., Cole, T. B., & Furlong, C. E. (2005). Modulation of paraoxonase (PON1) activity. Biochemical Pharmacology, 69(4), 541–550.

- Crabb, D. W., Matsumoto, M., Chang, D., & You, M. (2004). Overview of the role of alcohol dehydrogenase and aldehyde dehydrogenase and their variants in the genesis of alcohol-related pathology. Proceedings of the Nutrition Society, 63, 49–63.

- Dolinoy, D. C., Huang, D., & Jirtle, R. L. (2007). Maternal nutrient supplementation counteracts bisphenol A-induced DNA hypomethylation in early development. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 104, 13056–13061.

- Duhl, D.M.J., Vrieling, H., Miller, K. A., Wolff, G. L., & Barsh, G. S. (1994). Neomorphic agouti mutations in obese yellow mice. Nature Genetics, 8(1), 59–65.

- Earle, D. P., Bigelow, F. S., Zubrod, C. G., & Kane, C.A. (1948). Studies on the chemotherapy of the human malarias: IX. Effect of pamaquine on the blood cells of man. Journal of Clinical Investigation, 27, 121–129.

- Eriksson, M., Brown, W. T., Gordon, L. B., Glynn, M. W., Singer, J., Scott, L.,…Collins, F. S. (2003). Recurrent de novo point mutations in lamin A cause Hutchinson-Gilford progeria syndrome. Nature, 423, 293–298.

- Feitshans, I. L. (1989). Law and regulation of benzene. Environmental Health Perspectives, 82, 299–307.

- Hudson Alpha Institute for Biotechnology. (2009). Epigenetics. Retrieved from http://archive.hudsonalpha.org/education/outreach/basics/epigenetics

- Johnstone, R. W. (2002). Histone-deacetylase inhibitors: Novel drugs for the treatment of cancer. Nature Reviews: Drug Discovery, 1(4), 287–299.

- Omenn, G. S., & Motulsky, A. G. (2006). Ecogenetics: Historical perspectives. In D. L. Eaton & L. G. Costa (Eds.), Gene-environment interactions: Fundamentals of ecogenetics (chap. 1). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

- Rothman, N., Smith, M. T., Hayes, R. B., Traver, R. D., Hoener, B., Campleman, S.,…Ross, D. (1997). Benzene poisoning, a risk factor for hematological malignancy, is associated with the NQO1 609C → T mutation and rapid fractional excretion of chlorzoxazone. Cancer Research, 57, 2839–2842.

- Silver, K., & Sharp, R. R. (2006). Ethical considerations in testing workers for the -Glu69 marker of genetic susceptibility to chronic beryllium disease. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 48(4), 434–443.

- Woods, J. S., Heyer, N. J., Echeverria, D., Russo, J. E., Martin, M. D., Bernardo, M. F.,…Farin, F. M. (2012). Modification of neurobehavioral effects of mercury by a genetic polymorphism of coproporphyrinogen oxidase in children. Neurotoxicology and Teratology, 34, 513–521.

- Woods, J. S., Heyer, N. J., Russo, J. E., Martin, M, D., Pillai, P, B., Bammler, T. K., & Farin, F. M. (2014). Genetic polymorphisms of catechol-O-methyl transferase modify the neurobehavioral effects of mercury in children. Journal of Toxicology and Environmental Health: Part A, 77, 293–312.

For Further Information

- Costa, L. G., & Eaton, D. L. (Eds.). (2006). Gene-environment interactions: The fundamentals of ecogenetics. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

- Kari, E., North, K. E., & Martin, L. J. (2008). The importance of gene-environment interaction implications for social scientists. Sociological Methods & Research, 37(2), 164–200.

- Kelada, S. N., Eaton, D. L., Wang, S. S., Rothman, N. R., & Khoury, M. J. (2003). The role of genetic polymorphisms in environmental health. Environmental Health Perspectives, 111, 1055–1064.

- National Institute for Environmental Health Sciences. (2014). Gene-environment interaction. Available at http://www.niehs.nih.gov/health/topics/science/gene-env