2. Conservation and utilization of ecosystem services

3. Conservation of provisioning ecosystem services

4. Conservation of regulating ecosystem services

5. Conservation of cultural ecosystem services

6. The future of ecosystem services in conservation planning

Ecosystem services have not been traditional targets of biodiversity conservation efforts. Researchers, practitioners, and policy makers have focused their attention on genes, populations, species, or ecosystems. As societal interest in ecosystem services grows, however, these may provide an improved platform for communicating and quantifying their value to humans and thus improving our understanding of the dependence of our well-being on nature and ecosystem services. Once this link is firmly established, conservation of ecosystem services should be a more natural societal choice.

biological diversity. The variety and variability of all forms of life on Earth, encompassing the interactions among them and the processes that maintain them.

ecosystem services. The benefits people obtain from ecosystems. They can be of four primary types: provisioning, regulating, cultural, and supporting ecosystem services.

ecosystem service trade-off. Reduction of the provision of one ecosystem service as a consequence of increased use of another ecosystem service. They arise from management choices made by humans, which can change the type, magnitude, and relative mix of services provided by ecosystems.

Millennium Ecosystem Assessment. A global assessment carried out between 2001 and 2005 that involved more than 1360 experts worldwide and had the objectives of assessing the consequences of ecosystem change for human well-being and establishing the scientific basis for conservation and sustainable use of ecosystem services.

systematic conservation planning of ecosystem services. A scientific process for integrating social and biological information, to support decisionmaking about the location, configuration, and management of areas designated for the conservation and sustainable use of ecosystem services.

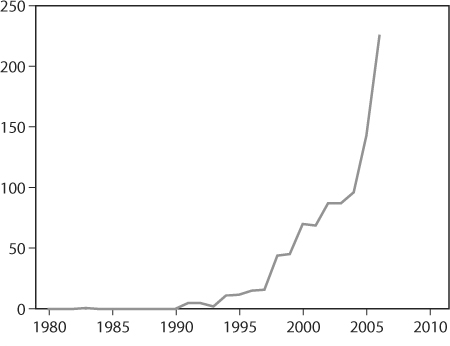

The visibility of the term ecosystem services recently exploded in the scientific literature: the total number of references accumulated by the late 1990s is smaller than the figure for 2005 or 2006 alone (figure 1). Attempts to preserve, restore, or enhance ecosystem services, however, clearly predate this. The first national park of the world, Yellowstone National Park, located in the northwestern United States, was established in 1872. A remarkable combination of unique geological features, striking landscapes, and abundant wildlife were preserved “for the benefit and enjoyment of the people”—in other words, for the cultural ecosystem services (ES) provided to humans. As an even earlier example, the entire global herd of Père David’s deer (Elaphurus davidianus) descends from a few animals kept for recreation in the Imperial Hunting Park south of Beijing (a cultural ES)—the deer is believed to have become extinct in the wild during the Ming Dynasty (1368–1644). The Inca empire arose in Peru in the thirteenth century and thrived in part because of its effective management of provisioning ES, such as maize (Zea mays) cultivation and herding of llamas (Lama glama). Soils, a supporting ES, were conserved by terracing the mountainside. Between 300 BC and AD 200, Rome built 11 major aqueducts, developed by the Roman Empire to service its roughly 1 million inhabitants. Major engineering achievements allowed the emperor, rich citizens, and the general public to access a network of water fountains within the city, never located more than 100 m apart. Water, a provisioning ES, was actively managed and conserved by Romans two millennia ago.

Figure 1. Number of times that the term ecosystem services appears in the article database of the ISI Web of Knowledge (http://www.isiwebofknowledge.com/) between 1980 and 2006. Search was conducted by entering “ecosystem services” in the topic field of the search engine.

Given how recently “ecosystem services” entered the conservation jargon, however, there are not many examples where conservation activities have been explicitly linked to ecosystem services. However, there are many examples where the motivation of a conservation action has been the implicit conservation of an ES. The IV Worlds Park Conference, held by the World Conservation Union (IUCN) in 1992, concluded that “protected areas are about meeting people’s needs,” and that they should be “part of every country’s strategy for sustainable management and the wise use of its natural resources.” In a follow-up guidelines document, published in 1994, IUCN identified six types of protected areas:

In the context of ES, types I–III focus on all but provisioning ES, whereas types IV–VI are primarily concerned with provisioning and cultural ES. In all cases, however, the goods and services provided by nature are clearly identified. Even type I protected areas, which are set aside for strict protection, still are able to provide ES, such as “genetic resources,” “ecologicalprocesses,” “education,” and “spiritual well-being.”

The recognition that human interests must be taken into consideration when areas of land are set aside for conservation purposes goes one step further in the Man and the Biosphere Programme (MAB) of the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). The cornerstones of MAB are biosphere reserves, or “areas of terrestrial and coastal ecosystems promoting solutions to reconcile the conservation of biodiversity with its sustainable use.” With over 500 sites in more than 100 countries, biosphere reserves are a global network that serves as testing grounds for “integrated management of land, water and biodiversity” (http://www.unesco.org/mab/BRs.shtml). A typical biosphere reserve fulfills conservation, development, and logistic objectives and is organized in a core area, a buffer zone, and a transition area (figure 2). Human settlements are an integral part of biosphere reserves, and research on how to best enhance human well-being while assuring environmental sustainability is key.

Although ES are never mentioned by IUCN or UNESCO, they are implicitly at the core of both initiatives. In fact, ES offer an excellent platform on which to build a general framework for all efforts to conserve biological diversity. The classical approach of focusing on genes, species, or ecosystems can be redefined in terms of the ES that they provide. For example, conservation efforts can be thought of as attempts to conserve different ES: (1) managers that enhance wild populations of birds, mammals, or fish for commercial or recreational users are conserving provisioning and cultural ES; (2) planners who seek to design an optimal reserve network for maximizing species diversity are targeting all of biological diversity and the various services that they provide; (3) ecological restoration of native vegetation around agricultural areas to increase native pollinator populations can be seen as enhancing their regulating ES; and (4) the protection of sacred burial grounds is equivalent to the conservation of a cultural ES.

The challenge of focusing biodiversity conservation on ES is that these services are not independent of each other. A decision to conserve one ES may influence the delivery of another, either positively or negatively. For example, protecting a watershed for the provision of water may enhance other provisioning ES, such as wild foods, genetic resources, or biochemicals; help improve regulating ES, such as air quality, erosion control, and water quality; and strengthen cultural ES, such as aesthetics, recreation, and tourism. But setting aside land for conservation also has opportunity costs, and some ES are forgone: timber cannot be extracted, crops cannot be planted; livestock cannot graze; and access to wild foods may be limited. How such a policy impacts human well-being will depend on the relative importance of the ES that are enhanced versus those that are forgone or degraded.

Figure 2. Schematic of the zones of a biosphere reserve. The core area is the only one that requires legal protection (e.g., national park, nature reserve) and where human activities tend to be limited to research and monitoring. Human settlements are located in the buffer zone or the transition area. Low-intensity economic activities are carried out in the buffer zone, and allowed uses in the transition area tend to be more diverse. (http://www.unesco.org/mab/BRs.shtml)

When the provision of one ES is reduced as a consequence of increased use of another, a trade-off is said to have taken place. Trade-offs are an integral component of decisions related to the management of ES, as they are likely to be inevitable under many circumstances. In some cases, a trade-off may be the consequence of an explicit choice, but in others, trade-offs arise without premeditation or even awareness that they are taking place. These unintentional trade-offs happen when we are ignorant of the interactions among ecosystem services or when we are familiar with the interactions but our knowledge about how they work is incorrect or incomplete.

As human societies expand across the wilderness areas of the world, the emphasis on different ES shifts as well (figure 3). Initially, people occupy wildlands, land is cleared for small-scale agriculture, and population begins to grow. The primary focus is agricultural production, and other ES are traded off against the provision of food, fiber, fuel, etc. Often subsistence lifestyles are gradually replaced by large-scale agricultural operations and urban areas, and attention shifts to regulating ES: as the human domination of the landscape increases, processes such as water regulation and purification must be enhanced. In the final stages, restoration or protection that focuses on recreation may come to dominate. The main point is that the value placed on different ES will change as societies develop and also change in ways that depend on culture and history.

Figure 3. Schematic trajectory of land-cover changes from before human settlement to the human domination of the landscape. (From Rodriguez et al., 2006)

In the following three sections, I present a series of examples of recent explicit or implicit efforts to conserve ES, organized around the Millennium Assessment (MA) categories for ES—provisioning, regulating, and cultural—and focusing on ES identified by the MA as degraded. The list of cases is illustrative, not exhaustive; for each type of ES, I selected two examples. Supporting services, the fourth category of ES identified by the MA, are underlying services necessary for the production of all other ecosystem services. But because supporting ES are not used directly by people, the focus of the following sections is on the other three types, which are subject to being degraded or enhanced by humans.

Provisioning services are products obtained from ecosystems. The MA examined the condition of 11 provisioning ES, six of which were considered degraded: capture fisheries, wild food products, wood fuel, genetic resources, biochemicals, and fresh water. Timber, fiber, crops, livestock, and aquaculture either showed mixed results or appeared to have been enhanced during the period examined by the MA. Examples regarding fisheries and fresh water are briefly presented below.

Roughly one-fourth of marine fisheries are overexploited or considerably depleted. Global marine fish harvests peaked in the late 1980s and have declined ever since. Over a billion people depend on fish as their primary or only source of protein, especially in developing countries.

Fishery exclusion areas, or marine reserves characterized by being closed to all forms of fishing, are emerging as a successful tool for managing fisheries in a wide diversity of habitats, such as coral reefs, kelp forests, seagrass beds, mangrove swamps, and the deep sea. Likewise, they work for a variety of fishing styles, including various recreational, artisanal, and industrial fisheries. Exclosures allow an increased reproductive output of fish stocks, increasing the harvest outside of the reserves (Gell and Roberts, 2003, present a comprehensive review of the topic).

The Soufrière Marine Management Area is located in the Caribbean island of Saint Lucia. It was created in 1995, spanning 11 km of coast. The reserve included several no-take areas within the island’s fringing coral reefs as well as areas open to fishing located mostly along beaches. Within the following 6 years, commercial fish biomass increased fourfold within the no-take areas and threefold in the fishing beaches. Total catch and catch per unit effort of local fishers also significantly increased.

Success of this initiative was linked to the spatial design of the network, which interspersed no-take areas among other uses. Fishers complied with the reserve but took advantage of the distribution of no-take areas by placing their fishing gear near the boundaries of reserve and harvesting the fish that “spilled over” into the areas open to fishing. In this way, there was a “balance” between enhancing provisioning services and preserving biodiversity—more species, or a greater abundance of existing species, could potentially be saved by eliminating fishing altogether, but this solution contains a recognition that fishing provides an important provisioning ES.

Limited access to fresh water is a major global problem, affecting 1–2 billion people worldwide, with consequences over the production of food, human health, and economic development. Roughly 1.7 million deaths occur every year because of poor water quality or inadequate sanitation. Global freshwater use is estimated to expand by 10% between 2000 and 2010. Forests and montane ecosystems remain the primary source of water for two-thirds of the global population, together accounting for 85% of the total runoff.

The establishment of protected areas is often opportunistic, without any explicit plan. Whatever is easily available is set aside first, particularly if lands are of low economic value or have no other competing uses (e.g., Yellowstone). The history of protected areas in Venezuela, however, followed another track. The country’s first national park, Henri Pittier National Park, was established in 1937, protecting the headwaters of several rivers that drain into the city of Maracay and several major cacao (Theobroma cacao) plantations and towns along the Caribbean coast. At present, Venezuela has 43 national parks, covering over 13 million hectares. The majority of national parks are found along the country’s northern mountain ranges (plate 21), in the vicinity of large cities and agricultural areas. Canaima National Park, one of Venezuela’s largest national parks (30,000km2), includes the high watershed of the Caroní River. Guri Dam, located in the lower Caroní, produces electricity equivalent to 300,000 oil barrels per day. Water conservation has been the leading justification for the establishment of national parks. Effective and equitable distribution of this water still remains a problem to be solved.

Regulating services are the benefits obtained from the regulation of ecosystem processes. The MA assessed the status and trends of 10 regulating ES and concluded that seven are degraded: air quality regulation, regional and local climate regulation, erosion regulation, water purification, pest regulation, pollination, and natural hazard regulation. The three remaining regulating ES—water regulation, disease regulation, and global climate regulation—were classified as mixed or enhanced. Below, I present examples of water purification and pollination.

Mangroves are woody plants that develop naturally along tropical coastlines and in subtropical areas bathed by warm currents. They form wetlands that supply numerous ecosystem services, such as coastal erosion protection, improvement of water quality (by absorbing pollutants), and organic matter accumulation. Artificial mangrove wetlands have been used in Colombia to remediate lands degraded by the oil industry and to remove pollutants from contaminated waters.

In 1994, the Colombian Petroleum Institute initiated a project for the bioremediation of an area located more than 600km from the coast and at 75m above sea level, inundated by wastewaters of the petroleum industry, and characterized by their high contents of chloride (>30 parts per thousand), iron (up to 13%), and barium (65ppm). Stands of red mangrove (Rhizophora mangle), black mangrove (Avicennia germinans), and white mangrove (Laguncularia racemosa) were created within an artificial lagoon in the polluted area. Mangroves demonstrated a high capacity for extracting and isolating pollutants from the surrounding water. The salinity of water before treatment was 42,000ppm, whereas at the exit of the artificial lagoon, it had declined to 3300ppm. By 2000, 6 years after initiation of the project, plant cover had been fully restored; before treatment, no woody plants grew there.

Another project involving an artificial mangrove wetland was carried out by a shrimp-farming company in San Antero, Cóirdoba Department, with the objective of treating the wastewaters of their shrimp farm. The wetland was built 0.5 m above the maximum tide level, taking advantage of the topography so that the area selected would easily form an artificial lake. Red mangrove trees were planted from seedlings and embryos. Shrimp farms used water from a nearby wetland, the Ciénaga de Soledad. This “natural” water source fills the shrimp ponds, and flows into a wastewater channel that feeds the artificial wetland, or the “collector.” One year of monitoring revealed that the artificial wetland was highly efficient in significantly reducing total suspended solids and biological oxygen demand, from 145 to 94mg/liter and 14 to 9 mg/liter, respectively. In fact, water quality after exiting the facility was superior to that at the Ciéinaga de Soledad itself. Six years after it was built, the wetland had become a true refuge for local biodiversity, and commercially valuable fish had naturally established themselves. In 2003, a study analyzed the catch of 24 fishing trips by artisanal fishers; each trip consisted of 5 hr in one small nonmotorized boat and three fishers. After a combined effort of 120hr of fishing, they produced 200kg of fish (1.7 kg/hr). Each fisher caught 2.9kg/day, representing about US$12/day. This is equivalent to a monthly income of US$240 (assuming 20 working days/month), which is 40% higher than Colombia’s 2006 minimum salary of approximately US$170/month.

Pollinators are involved in the sexual reproduction of roughly 80% of the 300,000 species of flowering plants of the world. Their regulating ES enhances provisioning ecosystem services, such as the production of food crops, as well as any other ES linked to flowering plants (primarily provisioning and cultural ES). Over 200,000 pollinators are known, and roughly 10% of them are bees. Animal pollinators are predominantly insects (Hymenoptera: bees, wasps, and ants; Coleoptera: beetles; Diptera: flies; Lepidoptera: butterflies and moths; Thysanoptera: thrips), mammals (including bats, marsupials, monkeys, and procyonids), and birds (primarily, but not exclusively, hummingbirds).

The most important managed pollinator in the United States and Europe, the honeybee (Apis mellifera), recently has shown a clear decrease in population size. Although the data supporting wild pollinator trends are less reliable, there is evidence of the decline in several other bee species (especially bumblebees) as well as some butterflies, bats, nonflying mammals, and hummingbirds. In the United States, pollination by insects produces US$40 billion annually, and the value of crop pollination by honeybees alone is estimated at US$6 billion per year in Europe. The global figure for the value of pollinators has been estimated to be on the order of US$120–200 billion per year (Díaz et al., 2005).

Pollinator conservation is a very active discipline. The African Pollinator Initiative summarized a series of recommendations, which include conserving and restoring natural habitat, growing flowering plants preferred by pollinators, promoting mixed farm systems, establishing nectar corridors for migratory species, and providing nesting and feeding habitats alongside croplands. A mosaic of materials such as dry wood, bare ground, mud, resin, sand, carrion, host plants, and caves are needed to maintain pollinator diversity at any particular site.

In Mexico, several species of columnar cacti, plants in the genus Agave, and trees in the Family Bombacaceae rely on bats for their sexual reproduction. Founded in 1994, the Program for the Conservation of Migratory Bats (PCMB) focuses on research and environmental education for the protection of bats by conserving habitat along migratory corridors. The Brazilian free-tailed bat (Tadarida brasiliensis), for example, overwinters in South and Central Mexico, and migrates north each spring, forming very large breeding colonies in northern Mexico and the southwestern United states that may be as large as 20 million individuals. They perform a natural pest-control service, feeding on vast quantities of insects during the migration, but especially while at their breeding grounds; in South-Central Texas, the value of the service provided by breeding free-tailed bats feeding on cotton bollworm (Helicoverpa zea) is estimated at about US$1 million per year. By highlighting the economic value of bats to the Mexican government, PCMB succeeded in promoting an amendment of the national Wildlife Law to include all caves and crevices as protected areas, thus conserving key habitat for bats and enhancing their ecosystem services.

Cultural ES are nontangible benefits that people obtain from ecosystems through spiritual enrichment, cognitive development, reflection, recreation, and aesthetics. The MA assessed the status of three cultural services: spiritual and religious services, aesthetic values, and recreation and tourism. The first two were classified as degraded, and the last was considered mixed. Below, I focus on aesthetic values and, although the evidence is mixed, on recreation and ecotourism.

Studies carried out primarily in industrialized countries have shown that people tend to prefer nonurban over built environments, and there is a range of preferences between wild and cultivated landscapes. In other words, the appreciation of aesthetic ES is a major feature of human behavior. Research shows that people rate the scenic beauty of natural scenes to be higher that urban images; natural settings that are healthy, lush, and green are perceived as more attractive, especially when contrasted with arid habitats; parklike settings, which are safe and likely to provide primary needs such as food and water, are also favored; and patients recover from surgical interventions faster and with less medical attention in rooms with a natural view than when they are looking at a blank wall.

This is not a recent phenomenon, and it appears to be prevalent over different cultures and times. The Hanging Gardens of Babylon, one of the original seven wonders of the world, were built to showcase the beauty of trees and other plants. “Imperial gardens” were carefully designed, aesthetically pleasing landscapes integrated with the palaces of Chinese dynasties. In modern times, people continue to exercise these preferences when making choices about where to live: a study of 3000 real estate transactions in the Netherlands showed that house prices were higher when the property had a garden facing large water bodies or open space. Billions of dollars are spent every year worldwide on lawn and garden maintenance in homes; in the United States, for example, the annual figure is approximately US$40 billion.

Tourism generates approximately 11% of global GDP and employs over 200 million people. Approximately 30% of these revenues are related to cultural and nature-based tourism, and nature travel is increasing between 10% and 30% per year. The tourism industry was identified by Agenda 21 as one of the few industries with the potential of simultaneously improving the economic condition of nations and the general state of the environment.

Approximately 50 million people in the United States, or 20% of the population, are bird watchers. These are people who travel away from their homes with the primary purpose of observing birds. For these trips, birders annually spend around US$20 billion on equipment and US$7 billion on travel. The overall economic output of this process is estimated at US$85 billion, generating US$13 billion in state and income taxes and creating more than 850,000 jobs. This means that each of the 1000 bird species in the United States has, on average, a value for bird watchers that is equivalent to US$85 million in overall economic output, US$13 million in tax revenue, and 850 jobs.

The Ecotourism Society defines ecotourism as “travel to natural areas that conserves the environment and sustains the well-being of local people.” For developing countries, ecotourism is often seen as one of the primary economic alternatives to support the conservation of threatened ecosystems. In Kenya and Costa Rica, for example, tourism brings in several hundred million dollars per year, much of it from tourists interested in nature and wildlife. The challenges are to assure that the presence of tourists does not unacceptably degrade ecosystems, the natural capital of ecotourism, and that revenues indeed reach local communities. Evidence to date suggests that a healthy dose of skepticism and caution are warranted. The Galáipagos Islands attract more than 62,000 tourists every year, drawn by the promise of spectacular seascapes and a unique array of animals and plants. The majority of the islands’ inhabitants (80%) receive a share of the income generated by this economic activity, which has been designed such that human impact is kept to the minimum possible. At a first glance, one might consider this a win-win situation, but trade-offs are clearly taking place. The economic success of Galáipagos has attracted people from the mainland, who migrate to the islands in search of jobs. The growth in human population has led to increased pressure on the limited infrastructure and on local provisioning ES such as fish. But the biggest problem is that local communities only receive about 15% of the income generated by tourism; most of the funds are captured by large companies that provide luxury transportation and lodging.

Systematic conservation planning seeks the adequate representation of species, or other biological or physical attributes of landscapes, in a network of nature reserves. Numerous algorithms have been developed for the identification of priority sites for inclusion in existing reserve networks. In recent years, efforts have centered on optimizing the investment of limited funds and examining the availability of human resources for implementing conservation priorities. Ecosystem services, however, are not typically considered in systematic conservation planning. In part, this is probably because ES have not been adequately quantified at the scale of large geographic areas, such as nations, continents, or the globe. In other words, data on how ES supply varies spatially or temporally are simply unavailable. But two recent studies, one carried out in the Atlantic Forests of Paraguay (Naidoo and Rickets, 2006) and another in the Californian Central Coast Region of the United States (Chan et al., 2006), have began to lay the framework for explicitly integrating ES into systematic conservation planning.

In the Paraguayan Atlantic Forests example, economic costs and benefits of the conservation of this highly threatened landscape were assessed in terms of five ecosystem services: wild food (bush meat), timber, biochemicals, carbon sequestration, and existence values. As one might expect, spatial variability of costs and benefits were large, although carbon sequestration dominated among ES values. Their contrast of three potential corridor designs to improve connectivity to the core area of the landscape allowed researchers to identify one that had net benefits that were three times higher than the other two when all five ES were considered.

The second study also carried out a spatially explicit analysis, but in this case, researchers compared priority areas based on biodiversity conservation, with those generated from the provision of water, forage production, water regulation (flood control), crop pollination, carbon sequestration, and recreation. They found relatively low correlation between the spatial distribution of ES supplies and little overlap between priority sites identified from each variable individually. Sites selected in terms of their importance to biodiversity did not capture the benefits provided by ES. Network designs would thus have to consider the relative value placed on each ES by society in order to maximize the flow of benefits.

The question that remains is whether ES offer an appealing platform for a general framework for the conservation of biological diversity. The MA showed that humans have negatively impacted ES during the last 50 years and that natural capital has been eroded: of 24 ES examined by the MA, 15 are currently degraded globally. Tens of thousands of Web pages now refer to the MA (which generated its final published products in 2005), and nearly a million include the term ecosystem services. In contrast, biodiversity, a term first used in 1988, roughly when “ecosystem services” began to expand (figure 1), draws over 22 million hits. The “popularization” of ES, although apparently on the right track, still has a long way to go.

A global agenda for the conservation of ecosystem services would also need to overcome a series of major obstacles (Irwin et al., 2007):

These obstacles will sound familiar to anyone with practical experience in the conservation of biological diversity as well as the actions required to counteract them: increased availability and application of information on ES, stronger rights in the use and management of ES, management of ES at multiple temporal and spatial scales, improvement of accountability regarding the use of ES, and development of incentives to encourage sustainable use of ES. Ecosystem services, however, may still provide one of the best conceptual frameworks for posing conservation priorities to the general public. Because ES are the benefits people obtain from ecosystems, their value should be relatively easy to understand and to communicate.

Chan, Kai M. A., M. Rebecca Shaw, David R. Cameron, Emma C. Underwood, and Gretchen C. Daily. 2006. Conservation planning for ecosystem services. PLoS Biology 4: e379. Downloadable from http://www.plosjournals.org/.

Díaz, Sandra, David Tilman, Joseph Fargione, F. Stuart Chapin III, Rodolfo Dirzo, Thomas Kitzberger, Barbara Gemmill, Martin Zobel, Montserrat Vilà, Charles Mitchell, Andrew Wilby, Gretchen C. Daily, Mauro Galetti, William F. Laurance, Jules Pretty, Rosamond Naylor, Alison Power, and Drew Harvell. 2005. Biodiversity regulation of ecosystem services. In Rashid Hassan, Robert Scholes, and Nevilae Ash, eds. Ecosystems and Human Well-being: Current State and Trends, Volume 1. Findings of the Condition and Trends Working Group. Washington, DC: Island Press, 297—329. Downloadable from http://www.maweb.org/.

Eardley, Connal, Dana Roth, Julie Clarke, Stephen Buchman, and Barbara Gemmill, eds. 2006. Pollinators and Pollination: A Resource Book for Policy and Practice. Pretoria, South Africa: African Pollinator Initiative (API). Downloadable from http://pollinator.org/Resources/Pollination%20Handbook.pdf.

Gell, Fiona R., and Callum M. Roberts. 2003. The Fishery Effects of Marine Reserves and Fishery Closures. Washington, DC: World Wildlife Fund. Downloadable from http://www.worldwildlife.org/oceans/pubs.cfm.

Hassan, Rashid, Robert Scholes, and Neville Ash, eds. 2005. Ecosystems and Human Well-being: Current State and Trends, Volume 1. Findings of the Condition and Trends Working Group. Washington, DC: Island Press. Downloadable from http://www.maweb.org/.

Irwin, Frances, Janet Ranganathan, Mark Bateman, Albert Cho, Hernan Darío Correa, Robert Goodland, Anthony Janetos, David Jhirad, Karin Krchnak, Antonio La Viña, Lailai Li, Nicolàs Lucas, Mohan Munasinghe, Richard Norgaard, Sudhir Chella Rajan, Iokiñe Rodríguez, Guido Schmidt-Traub, and Frances Seymour. 2007. Restoring Nature’s Capital: An Action Agenda to Sustain Ecosystem Services. Washington, DC: World Resources Institute. Downloadable from http://pdf.wri.org/restoring_natures_capital.pdf.

IUCN. 1994. Guidelines for Protected Area Management Categories. Gland, Switzerland and Cambridge, UK: Commission on National Parks and Protected Areas (CNPPA) with the assistance of World Conservation Monitoring Centre (WCMC), and The World Conservation Union (IUCN). Downloadable from http://www.unep-wcmc.org/protected_areas/categories/eng/index.html.

Millennium Ecosystem Assessment. 2003. Ecosystems and Human Well-being: A Framework for Assessment. Washington, DC: Island Press. Downloadable from http://www.maweb.org/.

Millennium Ecosystem Assessment. 2005. Ecosystems and Human Well-being: Synthesis. Washington, DC: Island Press. Downloadable from http://www.maweb.org/.

Naidoo, Robin, and Taylor H. Ricketts. 2006. Mapping the economic costs and benefits of conservation. PLoS Biology 4: e360. DOI: 310.1371/journal.pbio.0040360. Downloadable from http://www.plosjournals.org/.

Rodríguez, Jon Paul, T. Douglas Beard Jr., Elena M. Bennett, Graeme S. Cumming, Steven J. Cork, John Agard, Andrew P. Dobson, and Garry D. Peterson. 2006. Trade-offs across space, time, and ecosystem services. Ecology and Society 11: 28. Downloadable from http://www.ecologyandsociety.org/vol11/iss1/art28/.