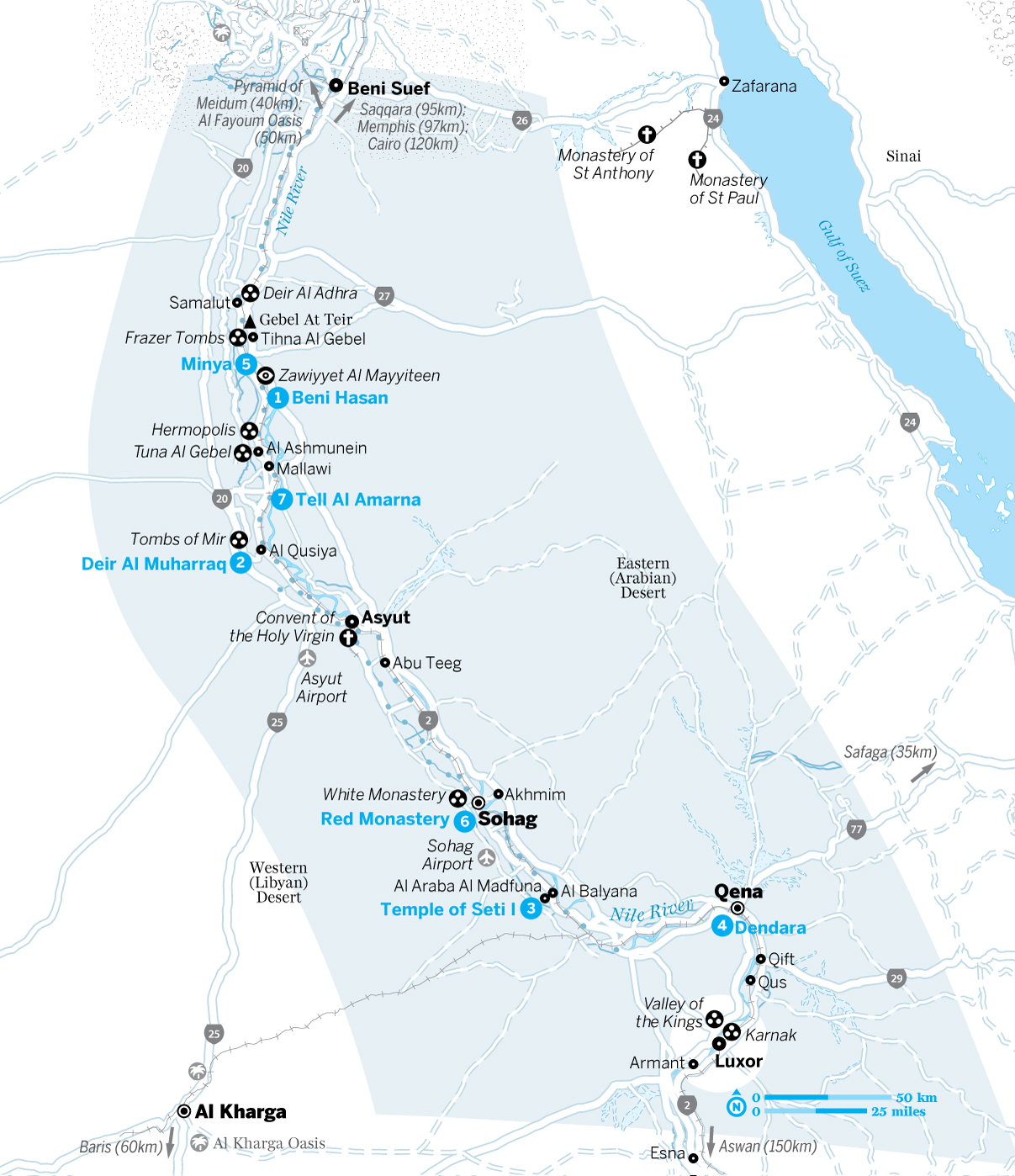

Northern Nile Valley

Beni Suef

Gebel At Teir & Frazer Tombs

Minya

Beni Hasan

Beni Hasan to Tell Al Amarna

Tell Al Amarna

Tombs of Mir

Deir Al Muharraq

Asyut

Sohag

Abydos

Qena

Northern Nile Valley

Why Go?

If you’re in a hurry to reach the treasures and pleasures of the south, it is easy to dismiss the places between Cairo and Luxor. But these less touristed parts of the country almost always repay what can be the considerable effort of a visit.

Some of this region remains less developed – you will see farmers still working by hand – but everyone here also has to grapple with modernity and its problems, with water and electricity shortages and, since the downfall of the Muslim Brotherhood, tension and security issues.

However much a backwater today, this region played a key role in Egypt’s destiny and there are archaeological sites to prove it – from the lavishly painted tombs at Beni Hasan and the remains of the doomed city of Akhetaten, where Tutankhamun was brought up, to the Pharaonic-inspired monasteries of the early Christian period.

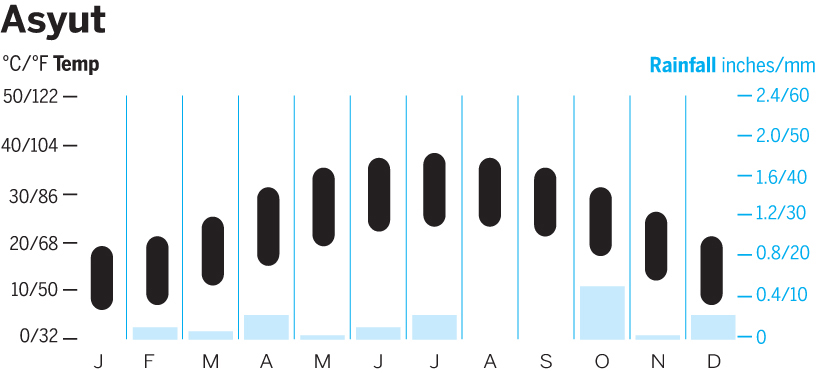

When to Go

- Apr Sham El Nessim, the spring festival, is celebrated in style in the region.

- Aug Millions of people arrive to celebrate the Feast of the Virgin outside Minya.

- Oct–Nov The ideal touring time, when the light is particularly beautiful.

Best Places to Stay

Northern Nile Valley Highlights

1 Beni Hasan Admiring lithe dancers, hunters and even wrestlers in these finely painted tombs.

2 Deir Al Muharraq Visiting the Coptic monastery to see why Copts claim to be heirs to the ancient Egyptians.

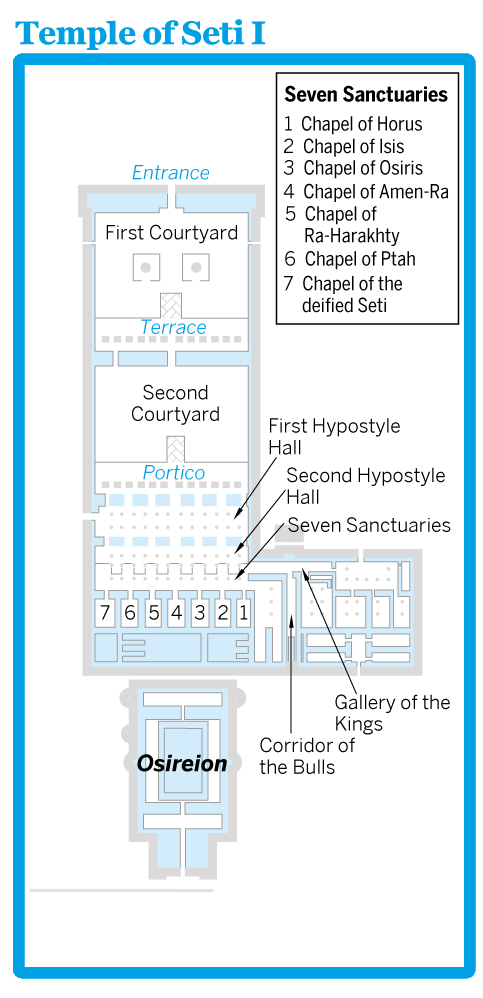

3 Temple of Seti I Gazing upon some of ancient Egypt’s finest temple reliefs in Abydos.

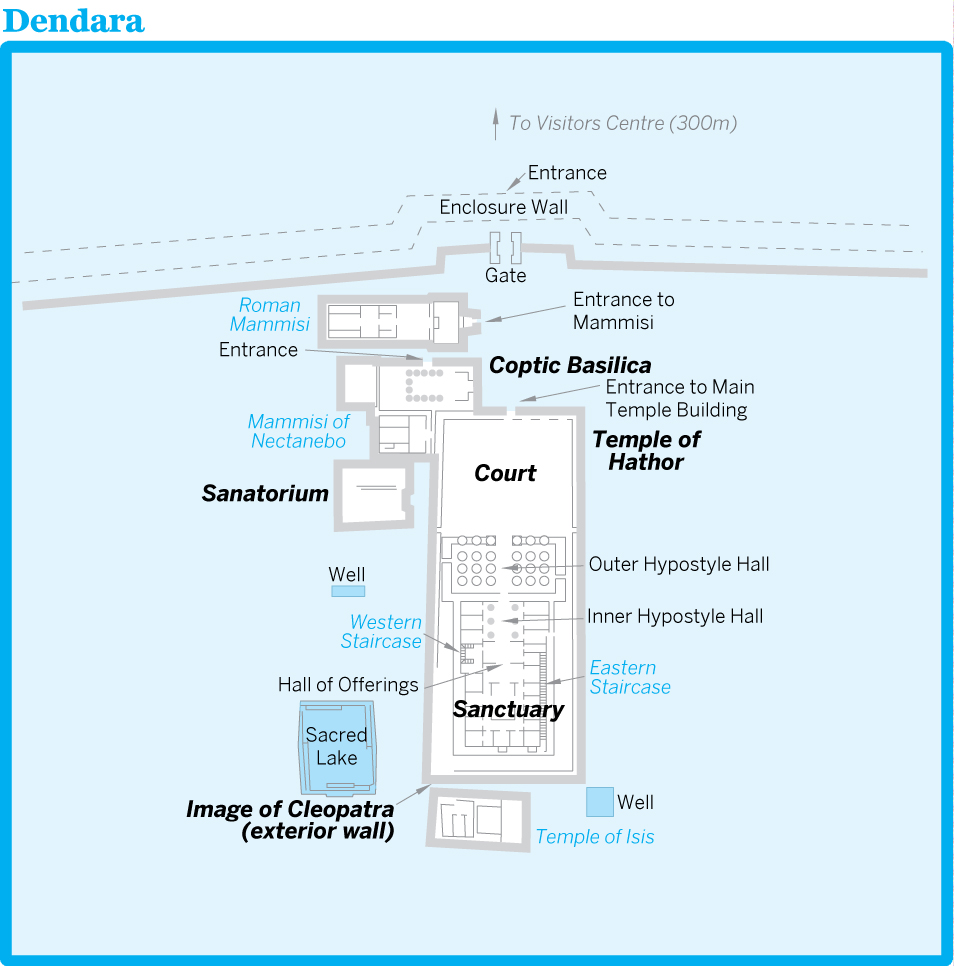

4 Dendara Marvelling at the Temple of Hathor, one of Egypt’s best-preserved temple complexes.

5 Minya Hanging out in the colonial-era centre.

6 Red Monastery Seeing the frescoes at one of the finest buildings from late antiquity.

7 Tell Al Amarna Wandering through the lush countryside around the doomed city of the heretic king Akhenaten.

History

For ancient Egyptians, Upper Egypt began south of the ancient capital of Memphis, beyond present-day Saqqara.

Egyptians divided the area that stretched between Beni Suef and Qena into 15 nomes (provinces), each with its own capital. Provincial governors and notables built their tombs on the desert edge, above the flood plain. Abydos, located close to modern Sohag, was once the predominant religious centre in the region as well as one of the country’s most sacred sites and a place of pilgrimage: Egypt’s earliest dynastic rulers were interred there and it flourished well into the Christian era.

When New Kingdom Pharaoh Akhenaten tried to break the power of the Theban priesthood, he moved his capital to a new city, Akhetaten (near modern Mallawi), one of the few places along the Nile that was not, at that point, associated with a deity.

Christianity arrived early in Upper Egypt. Sectarian splits in Alexandria and the popularity of the monastic tradition established by St Anthony in the Eastern Desert encouraged priests to settle in the provinces. The many churches and monasteries that continue to function in the area are testament to the strength of the Christian tradition: this area has the largest Coptic communities outside Cairo.

Dependent on agriculture, much of the area remained a backwater throughout the Christian and Islamic periods, although Qena and Asyut flourished as trading hubs: Qena was also the jumping-off point for the Red Sea port of Safaga, while Asyut linked the Nile with the Western Desert and the Sudan caravan route.

Today much of the region remains poor. Agriculture is still the mainstay of the local economy but cannot sustain the exploding population. The lack of any real industrial base south of Cairo has caused severe economic hardship, particularly for young people who drift in increasing numbers into towns and cities in search of work. Resentment at their lack of hope was compounded by the loss of remittances from Iraq: many people from this region who had found work abroad in the 1980s lost it with the outbreak of the first Gulf War. Religious militants exploited the violent insurrection that exploded in the 1990s, directing it towards the government in a bid to create an Islamic state. The insurrection was violently crushed. The Muslim Brotherhood found much support here after 2011, and there have been regular outbreaks of violence since the downfall of former president Morsi, most recently an attack on Copts heading to a monastery near Minya in May 2017. The unrest will continue until the causes of the unrest – poverty and thwarted hopes – are addressed.

Dangers & Annoyances

Travel restrictions have been in place on and off since the 1990s Islamic insurrection. Outbreaks of violence mean restrictions are in force at the time of writing, making this one of the most difficult regions to travel through, although Nile cruises between Cairo and Luxor have resumed. Although the situation remains fluid, some areas, particularly south of Sohag (Abydos and Dendara, for instance), can be visited without trouble.

8Getting Around

Trains are the best way of moving between cities in this part of Egypt. Foreign visitors are currently not permitted to travel by microbus, so the only alternative for shorter journeys is private taxi, and you might then find yourself being escorted by armed police.

Beni Suef

![]() %082 / Pop 272,850

%082 / Pop 272,850

Beni Suef is a provincial capital and a major transport hub between Cairo and Luxor, and the Red Sea and Al Fayoum. From antiquity until at least the 16th century, it was famous for its linen. In the 19th century, it was still sufficiently important (at least in the textile trade) to have an American consulate, but there is now little to capture the traveller’s interest beyond the sight of a provincial city at work.

1Sights

Beni Suef MuseumMuseum

(adult/student LE20/10; ![]() h

8am-4pm)

h

8am-4pm)

Next to the governorate building and behind the zoo, this museum is Beni Suef’s main attraction. There is a small but worthwhile collection of objects from the Old Kingdom to the Mohammed Ali period with good Ptolemaic carvings, Coptic weavings and 19th-century table-settings.

4Sleeping

City Center HotelHotel$

(

![]() %011-1007-2326; www.citychotel.net; Midan Al Mahatta; s/d LE265/295;

%011-1007-2326; www.citychotel.net; Midan Al Mahatta; s/d LE265/295; ![]() a

a![]() W)

W)

Around the corner from the forlorn Semiramis Hotel and across the square from the train station, this three-star 45-room hotel is popular with managers and white-collar workers posted to Beni Suef. Rooms are basic but have air-con, fridges and TVs. The 6th-floor restaurant serves a mixed menu including pizzas, chicken and pigeon for lunch and dinner, although you might need to order in advance.

Tolip InnHotel$$

(![]() %088-236-6993; www.tolipinnbns.com; Sharia Ahmed Orabi; s/d US$60/80;

%088-236-6993; www.tolipinnbns.com; Sharia Ahmed Orabi; s/d US$60/80; ![]() p

p![]() a

a![]() W

W![]() s)

s)

The newest and smartest address in Beni Suef, with spacious rooms, all with large flat-screen TVs, mini-bar, good internet and tea and coffee facilities. The restaurant serves a dull but reliable menu of local and European dishes, and there’s a large pool.

8Getting There & Away

The bus station is along the main road, Sharia Bur Said, south of the town centre. Buses run to Cairo, Minya, Al Fayoum and Zafarana. Microbuses also run the same routes. Depending on the security situation, you may be obliged to take a train or hire a private taxi.

There are frequent train connections north to Cairo and Giza (1st/2nd class LE39/23, 90 minutes to two hours), and south to Minya (LE39/23, 1½ hours).

Gebel At Teir & Frazer Tombs

Deir Al AdhraMonastery

(![]() h6am-dusk)

h6am-dusk)

The clifflike Gebel At Teir (Bird Mountain) rises east of the Nile, some 93km south of Beni Suef and 20km north of Minya. The mountain takes its name from a legend that all Egyptian birds paused here on the monastery’s annual feast day. Deir Al Adhra (Monastery of the Virgin) is perched 130m above the river and was formerly known as the Convent of the Pulley, a reminder of the time when rope was the only way of reaching the cliff top.

Coptic tradition claims that the Holy Family rested here for three days on their journey through Egypt. A cave-chapel built on the site in the 4th century AD is ascribed to Helena, mother of Byzantine Emperor Constantine. A 19th-century building encloses the cave, whose icon of the Virgin is said to have miraculous powers. The monastery, unvisited for most of the year, is mobbed by many thousands of pilgrims during the week-long Feast of the Assumption, culminating on 22 August.

You can get to the monastery by public transport (servees or microbus from Minya to Samalut and a boat across the river), but a private taxi from Minya shouldn’t cost more than LE100 to LE150 for the return trip.

Frazer TombsTomb

(adult/student LE30/15; ![]() h8am-4pm)

h8am-4pm)

Five kilometres south of Tihna Al Gebel, the Frazer Tombs date back to the 5th and 6th dynasties. These Old Kingdom tombs are cut into the east-bank cliffs and overlook the valley. Only two tombs are open and both are very simple, with eroded images and hieroglyphs but no colourful scenes. They are likely to appeal only if you have a passion for rarely visited sites.

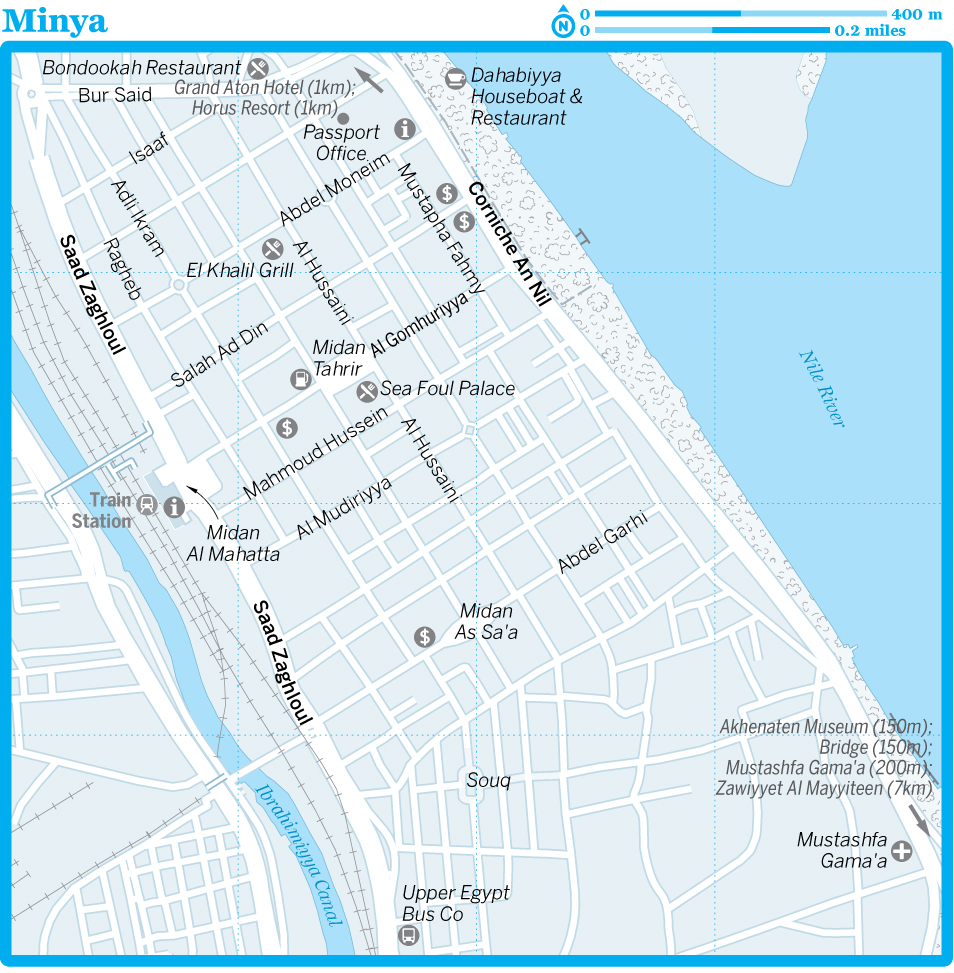

Minya

![]() %086 / Pop 283,000

%086 / Pop 283,000

Minya, the ‘Bride of Upper Egypt’ (Arousa As Sa’id), sits on the boundary between Upper and Lower Egypt. A provincial capital, its broad tree-lined streets, wide corniche and some great, if shabby, early-20th-century buildings make this one of the most pleasant town centres in Upper Egypt.

Once the hub of the Upper Egyptian cotton trade, its factories now process sugar, soap and perfume. The downturn in the local economy helped fuel an Islamist insurgency in the 1990s, which the government sent tanks and armoured personnel carriers to suppress. They did this again in 2013 to quell pro–Muslim Brotherhood protests. More recently, security was tightened in May 2017 following an attack on Coptic visitors to a monastery outside Minya in which 28 people died. In spite of the tension, Minya remains a good place to visit and its city centre retains the air of a more graceful era.

1Sights

Beyond the pleasure of strolling around the town centre and along the Nile corniche, against the background of the Eastern Hills, Minya doesn’t have many sights. That will change when the new Akhenaten Museum eventually opens. There is a souq (market) at the southern end of the town centre and the streets that run from it to Midan Tahrir are among the liveliest.

Hantours (horse-drawn carriages; per hour LE30 to LE40) can be rented for a leisurely ride around the town centre or along the corniche. Feluccas (Egyptian sailing boats; per hour LE50) can be rented at the landing opposite the tourist office for trips along the river.

Zawiyyet Al MayyiteenCemetery

On the east bank about 7km southeast of town, this large Muslim and Christian cemetery, called Zawiyyet Al Mayyiteen (Place of the Dead), consists of several hundred mudbrick mausoleums, many with beehive roofs. Stretching for 4km from the road to the hills and said to be one of the largest cemeteries in the world, it is an interesting sight.

Akhenaten MuseumMuseum

new Akhenaten Museum on the east bank is now complete, but no date has been set for its opening. If the Egyptian authorities can swing it, it will be home, for some months at least, to the iconic bust of Queen Nefertiti (now in Berlin) as well as treasures from the nearby Tell Al Amarna excavations.

4Sleeping

![]() oHorus ResortHotel$$

oHorus ResortHotel$$

(![]() %086-231-6660; www.horusresortminia.com; Corniche An Nil; s/d US$40/60;

%086-231-6660; www.horusresortminia.com; Corniche An Nil; s/d US$40/60; ![]() a

a![]() W

W![]() s)

s)

On the Nile about 1km from the centre, this remains our top-pick hotel although that is mostly because of the lack of competition. Staff are friendly and views of the Nile are good, but cleanliness and food standards have dropped since our last visit. The large riverside swimming pool and the playground make it popular with kids.

The popular riverside terrace serves cold beers, fresh juices and shisha; the restaurant serves a dire breakfast but some standard Egyptian as well as Italian dishes in the evening.

Grand Aton HotelHotel$$$

(![]() %086-234-2993, 086-234-2994; Corniche An Nil; s/d US$100/120;

%086-234-2993, 086-234-2994; Corniche An Nil; s/d US$100/120; ![]() a

a![]() W

W![]() s)

s)

Still referred to locally as the Etap (its former incarnation), the Grand Aton has emerged from a major renovation with the best rooms in town but the atmosphere of a mall more than a hotel. On the west bank of the Nile, many of the well-equipped bungalow rooms have great river views. Restaurants, a cafe/bar and pool.

5Eating & Drinking

![]() oBondookah RestaurantEgyptian $

oBondookah RestaurantEgyptian $

(Sharia Masaken El Gamaa; mains from LE45; ![]() hnoon-11pm)

hnoon-11pm)

The best grilled meat in Minya in an unfussy 2nd-floor restaurant. Grilled chicken, lamb chops, tagen (a stew cooked in a deep clay pot) and, best of all, kofta. There are salads, rice and bread, soft drinks and a good view through the large windows onto the busy street. Not somewhere to spend the evening, but good to refuel. The menu is in Arabic.

Sea Foul PalaceEgyptian$

(Midan Tahrir; mains from LE20)

Some of the best fuul and ta’amiyya in town from this takeaway beside the old Palace Hotel. Grab a bag-full and sit in the square, or up the road on the corniche, and watch the world go by.

El Khalil GrillEgyptian$$

(![]() %086-233-4433; Sharia Abdel Moneim; mains around LE65;

%086-233-4433; Sharia Abdel Moneim; mains around LE65; ![]() h11am-2am)

h11am-2am)

A popular, no-nonsense, reliable kebab and grill restaurant for when you need a meat fix, El Khalil is something of a legend in Minya. Kebabs (LE250 a kilo) are the main item. No alcohol, but there’s a really good juice bar next door.

Dahabiyya Houseboat & RestaurantCafe

(![]() %086-236-5596; Corniche An Nil;

%086-236-5596; Corniche An Nil; ![]() hnoon-11pm)

hnoon-11pm)

This old Nile sailing boat has been moored along the corniche near the tourist office for many years and is one of Minya’s most unusual addresses. The bedrooms downstairs are no longer for hire, but the top-deck cafe-restaurant remains popular with locals, especially for a coffee or cool drink on a warm evening.

8Information

The tourist office (MAP GOOGLE MAP; ![]() %086-236-0150; Corniche An Nil;

%086-236-0150; Corniche An Nil; ![]() h9am-3.30pm Sat-Thu) in the centre of town and facing the Nile might look derelict, but the willing staff should be able to help with basic information regarding hotels, excursions and onward travel. There’s also a branch (MAP;

h9am-3.30pm Sat-Thu) in the centre of town and facing the Nile might look derelict, but the willing staff should be able to help with basic information regarding hotels, excursions and onward travel. There’s also a branch (MAP; ![]() %086-234-2044) at the train station, although it is often closed.

%086-234-2044) at the train station, although it is often closed.

8Getting There & Away

Bus & Microbus

The Upper Egypt Bus Co (MAP GOOGLE MAP; ![]() %086-236-3721; Sharia Saad Zaghloul) has hourly services to Cairo (LE30, four hours) from 6am. Buses leave for Hurghada at 10.30am and 10.30pm (LE80, six hours).

%086-236-3721; Sharia Saad Zaghloul) has hourly services to Cairo (LE30, four hours) from 6am. Buses leave for Hurghada at 10.30am and 10.30pm (LE80, six hours).

A seat in a microbus or servees, if you are allowed to take one, will cost LE20 to Cairo and LE15 to Asyut.

Train

Trains to Cairo (1st/2nd class LE62/36, three to four hours) leave at least every 1½ hours starting at 4.25am. Trains heading south also leave fairly frequently, with the fastest trains departing from Minya between 11pm and 1am: Luxor (LE86/47, six to eight hours) and Aswan (LE109/59, eight to 11 hours), stopping at Asyut (LE39/26, two hours), Sohag (LE55/34, three to four hours) and Qena (LE78/44, five to seven hours).

Beni Hasan

The necropolis of Beni Hasan (adult/student LE60/40; ![]() h8am-4pm) occupies a range of east-bank limestone cliffs some 20km south of Minya. It is a superb and important location and has the added attraction of a rest house, although these days it is only occasionally open for drinks; you should bring your own water and food. Most tombs date from the 11th and 12th dynasties (2125–1795 BC), the 39 upper tombs belonging to nomarchs (local governors). Many remain unfinished and only four are currently open to visitors, but they are well worth the trouble of visiting for the fascinating glimpse they provide of the daily life and political tensions of the period.

h8am-4pm) occupies a range of east-bank limestone cliffs some 20km south of Minya. It is a superb and important location and has the added attraction of a rest house, although these days it is only occasionally open for drinks; you should bring your own water and food. Most tombs date from the 11th and 12th dynasties (2125–1795 BC), the 39 upper tombs belonging to nomarchs (local governors). Many remain unfinished and only four are currently open to visitors, but they are well worth the trouble of visiting for the fascinating glimpse they provide of the daily life and political tensions of the period.

A guard will accompany you from the ticket office, so baksheesh is expected (at least LE20). Try to see the tombs chronologically.

1Sights

Tomb of Baqet (No 15)Tomb

(adult /student LE60/40 incl all Beni Hasan tombs; ![]() h8am-4pm)

h8am-4pm)

Baqet was an 11th-dynasty governor of the Oryx nome (district). His rectangular tomb chapel has seven tomb shafts and some well-preserved wall paintings. They include Baqet and his wife on the left wall watching weavers and acrobats – mostly women in diaphanous dresses in flexible poses. Further along, animals, presumably possessions of Baqet, are being counted. A hunting scene in the desert shows mythical creatures among the gazelles.

The back wall shows a sequence of wrestling moves that are still used today. The right (south) wall is decorated with scenes from the nomarch’s daily life, with potters, metalworkers and a flax harvest, among others.

Tomb of Kheti (No 17)Tomb

Kheti, Baqet’s son, inherited the governorship of the Oryx nome from his father. His tomb chapel, with two of its original six papyrus columns intact, has many vivid painted scenes that show hunting, linen production, board games, metalwork, wrestling, acrobatics and dancing, most of them watched over by the nomarch. Notice the yogalike positions on the right-hand wall, between images of winemaking and herding. On the west-facing wall are images of 10 different trees.

![]() oTomb of Amenemhat (No 2)Tomb

oTomb of Amenemhat (No 2)Tomb

Amenemhat was a 12th-dynasty governor of Oryx. His tomb is the largest and possibly the best at Beni Hasan and, like that of Khnumhotep, its impressive facade and interior decoration mark a clear departure from the more modest earlier ones. Entered through a columned doorway, and with its six columns intact, it contains beautifully executed scenes of farming, hunting, manufacturing and offerings to the deceased, who can also be seen with his dogs.

As well as the fine paintings, the tomb has a long, faded text in which Amenemhat addresses the visitors to his chapel: ‘You who love life and hate death, say: Thousands of bread and beer, thousands of cattle and wild fowl for the ka of the hereditary prince…the Great Chief of the Oryx Nome…’

Tomb of Khnumhotep (No 3)Tomb

Khnumhotep was governor during the early 12th dynasty, and his detailed ‘autobiography’ is inscribed on the base of walls that contain the most detailed painted scenes. The tomb is famous for its rich, finely rendered scenes of plant, animal and bird life. On the left wall farmers are shown tending their crops while a scribe is shown recording the harvest. Also on the left wall is a representation of a delegation bringing offerings from Asia – their clothes, faces and beards are all distinct.

Speos ArtemidosMonument

(Grotto of Artemis; ![]() h8am-4pm)

h8am-4pm)

If the guardian allows, you can follow a cliffside track that leads southeast for about 2.5km and then some 500m into a wadi to the rock-cut temple called the Speos Artemidos, and referred to locally as Istabl Antar (Stable of Antar, an Arab warrior-poet and folk hero), but actually dedicated to the ancient Egyptian lion-goddess Pasht.

Dating back to the 18th dynasty, the small temple was started by Hatshepsut (1473–1458 BC) and completed by Tuthmosis III (1479–1425 BC). There is a small hall with roughly hewn Hathor-headed columns and an unfinished sanctuary. On the walls are scenes of Hatshepsut making offerings and, on its upper facade, an inscription describing how she restored order after the rule of the Hyksos, even though she reigned long after.

Expect to be accompanied by a police escort and a guard (who will want baksheesh).

Plundering the Past

Antiquity theft is nothing new in Egypt – people have been robbing tombs and other sites for millennia. But in the security void that followed Mubarak’s 2011 downfall, many sites were plundered across the country. With continuing economic hardship, more people have a motive to go digging, and looting continues to be widespread throughout Egypt. Famous sites, including the Egyptian Museum in Cairo, have suffered losses, but many more lesser-known places, including El Hibeh and Mallawi’s museum, have been plundered too. Although the unit of the Egyptian government charged with recovering antiquities has struggled to cope with the challenge, some major pieces have been recovered from salesrooms abroad. One of the loudest activists has been Dr Monica Hanna, an Egyptologist who happened to be inside the Mallawi Museum in 2013 when most of its 1000-plus antiquities were looted (the majority have since been recovered). Dr Hanna created Egypt’s Heritage Taskforce, one of several organisations helping to protect antiquities, but the threat remains.

8Getting There & Away

It may be possible to take a microbus from Minya to the east bank and then another heading south to Beni Hasan, but as elsewhere, this will take time and is often forbidden. A taxi from Minya will cost anything from LE200 to LE400, depending on your bargaining skills and how long you stay at the site.

Beni Hasan to Tell Al Amarna

Hermopolis

Hermopolis is the site of the ancient city of Khemenu. Capital of the 15th Upper Egyptian nome, its original Egyptian name, which translates as Eight Town, refers to four pairs of snake and frog gods that, according to one Egyptian creation myth, existed here before the first earth appeared out of the waters of chaos. This was also an important cult centre of Thoth, god of wisdom and writing, whom the Greeks identified with their god Hermes, hence the city’s Greek name, ‘Hermopolis’.

Although little remains of the wealthy ancient city, there are some wonderful things to see in and around its nearby cemetery, Tuna Al Gebel, although the seventeen mummies discovered in May 2017 will not be shown for some time.

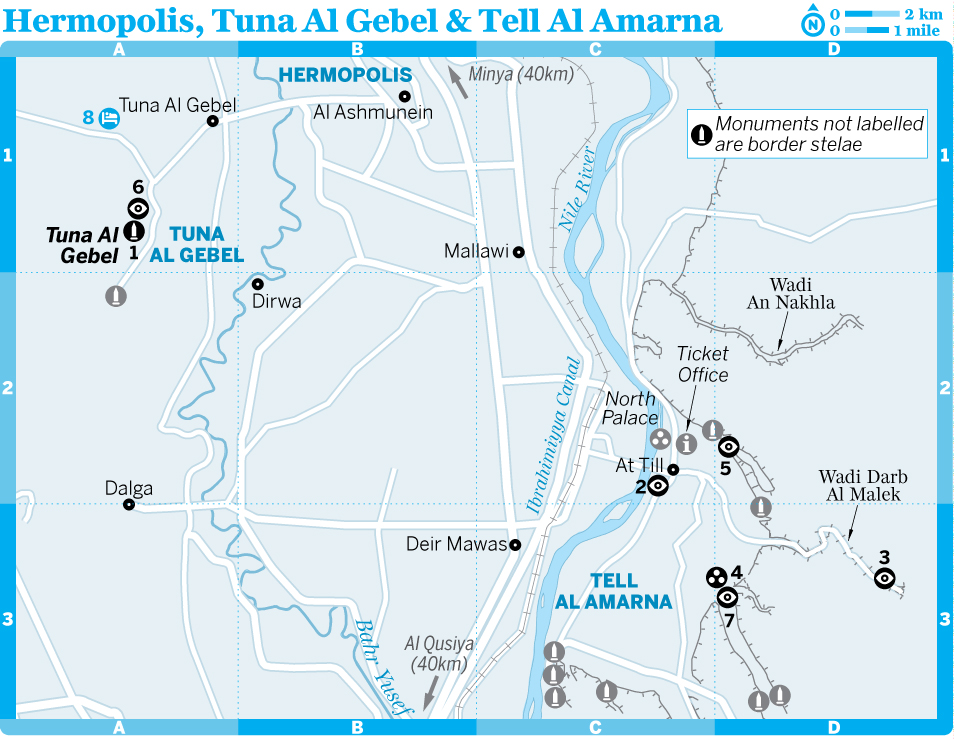

Hermopolis, Tuna Al Gebel & Tell Al Amarna

1Top Sights

1Sights

4Sleeping

1Sights

![]() oTuna Al GebelMonument

oTuna Al GebelMonument

(MAP; adult/student LE60/30; ![]() h8am-4pm)

h8am-4pm)

Tuna Al Gebel was the necropolis of Hermopolis; about 5km past the village of Tuna Al Gebel you’ll find the catacombs and tombs of the residents and sacred animals. The dark catacomb galleries once held many thousands of mummified ibis and baboons, both seen as the ‘living image of Thoth’. This wonderfully atmospheric subterranean cemetery is on two levels and extends for at least 3km, perhaps even all the way to Hermopolis.

There is an impressive shrine to the baboon god and a single human burial on the lowest level. You need a torch to get the most out of the galleries.

At one time Tuna Al Gebel belonged to Akhetaten, the short-lived capital of Pharaoh Akhenaten, and along the road you pass one of 14 stelae marking the boundary of the royal city. The large stone stele carries Akhenaten’s vow never to expand his city beyond this western limit of its farmlands and associated villages, nor to be buried anywhere else, although it seems he was eventually buried in the Valley of the Kings at Luxor. To the left, two damaged statues of the pharaoh and his wife Nefertiti hold offering tables; the sides are inscribed with figures of three of their daughters.

The most striking ruins at Hermopolis itself are two colossal 14th-century-BC quartzite statues of Thoth as a baboon. These supported part of Thoth’s temple, which was rebuilt throughout antiquity. A Middle Kingdom temple gateway and a pylon of Ramses II, using stone plundered from nearby Tell Al Amarna, also survive. There is also the remains of a Coptic basilica, which reused columns and even the baboon statues, though first removing their giant phalluses.

The site is several kilometres south of Hermopolis and then 5km along a road into the desert.

Tomb of PetosirisTomb

(![]() h8am-4pm)

h8am-4pm)

The Tomb of Petosiris, a high priest of Thoth from the late period (between the Persian and Greek conquests), is unusual because it copies the form of what has come to be labelled as a Ptolemaic temple. Like his elaborate sarcophagus in the Egyptian Museum in Cairo, Petosiris’s tomb is a fascinating mix. Although built in the reign of Nectanebo II, it shows both Persian and Greek influence. There are wonderful coloured reliefs of farming and of the deceased being given offerings, as well as others of daily life. The rectangular inner chamber is supported by four pillars. The burial chamber is beneath the centre of this space.

Tomb of IsadoraTomb

Isadora was a wealthy woman who drowned in the Nile during the rule of Antoninus Pius (AD 138–161). Her tomb has few decorations but it does contain the unfortunate woman’s mummy, with her teeth, hair and fingernails clearly visible.

OFF THE BEATEN TRACK

Sustainable Tourism

A rarity in Egypt, New Hermopolis (www.newhermopolis.org; half board per person UK£60-90 depending on group size; ![]() hOct-May;

hOct-May; ![]() p

p![]() s) is a sustainable farm and lodge run as a not-for-profit to provide educational opportunities for the local community. Accommodation is in bee-hive-domed rooms, water is drawn from the farm’s well, and power is mostly from solar panels. The centre has meeting rooms and currently only accepts groups of 12 to 24 people. It has some senior foreign Egyptologists as its patrons.

s) is a sustainable farm and lodge run as a not-for-profit to provide educational opportunities for the local community. Accommodation is in bee-hive-domed rooms, water is drawn from the farm’s well, and power is mostly from solar panels. The centre has meeting rooms and currently only accepts groups of 12 to 24 people. It has some senior foreign Egyptologists as its patrons.

8Getting There & Away

The slow village train service from Minya stops at Mallawi. From there, a network of microbuses runs around the villages. But unless you have time to burn, the only way to get around these sites is by taxi from Minya, perhaps continuing on to Asyut. Expect to pay up to LE1000, depending on the time you want to spend, the distance you want to travel and your bargaining skills.

Tell Al Amarna

In the fifth year of his reign, Pharaoh Akhenaten (1352–1336 BC) and his queen Nefertiti abandoned the gods and priests of Karnak and established a new religion based on the worship of a single deity, Aten, god of the sun disc.

They also built a new capital, Akhetaten (Horizon of the Aten), now known as Tell Al Amarna. This beautiful crescent-shaped plain, about 10km from north to south, sits between the river and a bay of high cliffs. After Akhenaten’s death, his successor changed his name from Tutankhaten to Tutankhamun (1336–1327 BC), re-established the cult of Amun and moved the capital back to Thebes. Akhetaten, capital of Egypt for some 30 years, fell into ruin.

Akhenaten’s doomed project is a complex site and the ruins, scattered across the desert plain, are hard to understand. Pre-trip planning helps: more detailed information is available on the excavation site www.amarnaproject.com.

1Sights

Two groups of cliff tombs, about 8km apart, make up the Tell Al Amarna necropolis (adult/student LE60/30; ![]() h8am-4pm Oct-May, to 5pm Jun-Sep), which features colourful, albeit defaced, wall paintings of life during the Aten revolution. Remains of temples and private or administrative buildings are scattered across a wide area: this was, after all, an imperial city. Buy tickets at the ticket office.

h8am-4pm Oct-May, to 5pm Jun-Sep), which features colourful, albeit defaced, wall paintings of life during the Aten revolution. Remains of temples and private or administrative buildings are scattered across a wide area: this was, after all, an imperial city. Buy tickets at the ticket office.

1 Central Ruins

Central CityTemple

The centre of Akhetaten contained the temple complex, the Great Palace and the King’s House. The temple complex contained two main buildings, a sanctuary and the Long Temple, 190m in length and divided into six courts. Along the south wall of the Long Table, archaeologists found the remains of 920 offering tables. This was separated from the King’s House by storerooms. The palace was built of stone and decorated with great care, with faience mouldings and tiles, and alabaster balustrades.

Archaeologists value the site because, unlike most places in Egypt, it was occupied for just one reign. Also, it has proved to be one of the most useful sites for understanding how people lived in this early period.

1 Northern Tombs

Tomb of Huya (No 1)Tomb

Huya was the steward of Akhenaten’s mother, Queen Tiye, and relief scenes to the right and left of the entrance to his tomb show Tiye dining with her son and his family. On the right wall of this columned outer chamber, Akhenaten is shown taking his mother to a small temple he has built for her and, on the left wall, sitting in a carrying chair with Nefertiti.

Tomb of Meryre II (No 2)Tomb

Meryre II was scribe, steward and ‘Overseer of the Royal Harem of Nefertiti’. To the left of the entrance, you will find a scene that shows Nefertiti pouring wine for Akhenaten.

Tomb of Ahmose (No 3)Tomb

Ahmose, whose title was ‘True Scribe of the King, Fan-Bearer on the King’s Right Hand’, was buried in the northern cemetery. Much of his tomb decoration was unfinished: the left-hand wall of the long corridor leading to the burial chamber shows the artists’ different stages. The upper register shows the royal couple on their way to the Great Temple of Aten, followed by armed guards. The lower register shows them seated in the palace listening to an orchestra.

Tomb of Meryre I (No 4)Tomb

High priest of the Aten, Meryre is shown, on the left wall of the columned chamber, being carried by his friends to receive rewards from the royal couple. On the right-hand wall, the royal couple are shown making offerings to the Aten disc; note here the rare depiction of a rainbow.

Tomb of Penthu (No 5)Tomb

Penthu, the royal physician and ‘First under the King’, was buried in a simple tomb. The left-hand wall of the corridor is decorated with images of the royal family at the Great Temple of Aten and of Pentu being appointed their physician.

Tomb of Panehsy (No 6)Tomb

The tomb of Panehsy, chief servant of the Aten in Akhetaten, retains the decorated facade most others have lost. Inside, scenes of the royal family, including Nefertiti driving her chariot and, on the right wall of the entrance passage, Nefertiti’s sister Mutnodjmet, later married to Pharaoh Horemheb (1323–1295 BC), with dwarf servants. Panehsy appears as a fat old man on the left wall of the passage between the two main chambers.

With the end of the ancient rites, Copts created a Christian community around these tombs and Panehsy’s tomb was converted to a church. Two of the first chamber’s four columns were removed by the Copts and an apse was added. The remains of painted angel wings can be seen on the walls.

1 Southern Tombs

Tomb of Mahu (No 9)Tomb

This is one of the best preserved southern tombs. The paintings show interesting details of Mahu’s duties as Akhenaten’s chief of police, including taking prisoners to the vizier (minister), checking supplies and visiting the temple.

Tomb of Ay (No 25)Tomb

This tomb, in the southern group, is the finest at Tell Al Amarna, with the images reflecting the importance of Ay and Tiyi. Scenes include the couple worshipping the sun and Ay receiving rewards from the royal family, including red-leather riding gloves. Ay wasn’t buried here, but in the west valley beside the Valley of the Kings at Thebes.

Ay’s titles were simply ‘God’s Father’ and ‘Fan-Bearer on the King’s Right Hand’, and he was vizier to three pharaohs before becoming one himself (he succeeded Tutankhamun and reigned from 1327 to 1323 BC). His wife Tiyi was Nefertiti’s wet nurse.

1 Royal Tomb of Akhenaten

Royal Tomb of AkhenatenTomb

(additional ticket adult/student LE40/20)

Akhenaten’s tomb (No 26) is in a ravine about 12km up the Royal Valley (Wadi Darb Al Malek), which divides the north and south sections of the cliffs and where the sun was seen to rise each dawn. It is similar in design and proportions to the royal tombs in the Valley of the Kings but with several burial chambers. The tomb decoration was painted on plaster, most of which has fallen, so very little remains.

The right-hand chamber has damaged reliefs of Akhenaten and his family worshipping Aten. A raised rectangular outline in the burial chamber once held the sarcophagus, which is now in the Egyptian Museum in Cairo (after being returned from Germany).

A well-laid road leads up the bleak valley. The guard will need to start up the tomb’s generator before allowing you inside. Akhenaten himself was probably not buried here, although members of his family certainly were. Some believe he was buried in KV 55 in Luxor’s Valley of the Kings, where his sarcophagus was discovered. The whereabouts of his mummy remains are a mystery.

8Information

You will be accompanied by a guard, who will be hanging around the ticket office (necropolis adult/student LE60/30; ![]() h8am-4pm Oct-May, to 5pm Jun-Sep).

h8am-4pm Oct-May, to 5pm Jun-Sep).

There is a cafe with toilets near the ticket office and another newer one near the Southern Tombs, but neither were open at the time of research. Be sure to bring food and drink with you.

8Getting There & Away

Even if the security situation allows it, getting to Tell Al Amarna by public transport remains a challenge, made more so by the ban on foreigners travelling on local microbuses. The site is so large that it is impossible to visit on foot, so the best way to visit is by taxi from Asyut, Minya or Mallawi and a long drive down the east bank of the river, or a crossing on the irregular car ferry (per car LE30). Expect to pay up to LE1000 depending on where you start and how long you want to stay. Be sure to specify which tombs you want to visit or your driver may refuse to go to far-flung sites.

Tombs of Mir

The necropolis of the governors of Cusae, the Tombs of Mir (adult/student LE40/20; ![]() h9am-4pm Sat-Wed) as they are commonly known (sometimes also Meir), were cut into the barren escarpment during the Old and Middle Kingdoms. Nine tombs are decorated and open to the public; six others were unfinished and remain unexcavated.

h9am-4pm Sat-Wed) as they are commonly known (sometimes also Meir), were cut into the barren escarpment during the Old and Middle Kingdoms. Nine tombs are decorated and open to the public; six others were unfinished and remain unexcavated.

Tomb No 1 and the adjoining tomb No 2 are inscribed with 720 Pharaonic deities, but as the tombs were used as cells by early Coptic hermits, many faces and names of the gods were destroyed. In tomb No 4, you can still see the original grid drawn on the wall to assist the artist in designing the layout of the wall decorations. Tomb No 3 features a cow giving birth.

The tombs are about 50 minutes’ drive from Asyut towards Minya. The bus will drop you at Al Qusiya. Few vehicles from Al Qusiya go out to the Tombs of Mir, so you’ll have to hire a taxi to take you there. Expect to pay at least LE70, depending on how long you spend at the site. A taxi from Asyut to Mir will cost LE20 to LE300. Ideally, you could combine this with a visit to Deir Al Muharraq.

Deir Al Muharraq

Deir Al MuharraqMonastery

(Burnt Monastery; ![]() h6am-dusk)

h6am-dusk)

Deir Al Muharraq, an hour’s drive northwest of Asyut, is a place of pilgrimage, refuge and vows, where the strength of Coptic traditions can be experienced. Resident monks believe that Mary and Jesus inhabited a cave on this site for six months and 10 days after fleeing from Herod, their longest stay anywhere they are said to have rested in Egypt. Tradition states that the Church of Al Azraq (the Anointed) sits over the cave and is the world’s oldest Christian church, consecrated around AD 60.

There has been monastic life here since the 4th century, although the current building dates from the 12th to 13th centuries. Unusually, the church contains two iconostases; the one to the left of the altar came from an Ethiopian Church of Sts Peter and Paul, which used to sit on the roof. Other objects from the Ethiopians are displayed in the hall outside the church.

The keep beside the church is an independent 7th-century tower, rebuilt in the 12th and 20th centuries. Reached by drawbridge, its four floors can serve as a mini-monastery, complete with its own small Church of St Michael, a refectory, accommodation and even burial space behind the altar.

Monks believe the monastery’s religious significance is given in the Book of Isaiah (19:19–21). The monastery has done much to preserve Coptic tradition: monks here spoke the Coptic language until the 19th century (at that time there were 190 of them) and, while other monasteries celebrate some of the Coptic liturgy in Arabic (for their Arabic-speaking congregation), here they stick to Coptic.

Also in the compound, the Church of St George (Mar Girgis) was built in 1880 with permission from the Ottoman sultan, who was still the official sovereign of Egypt. It is decorated with paintings of the 12 apostles and other religious scenes, its iconostasis is made from marble and many of the icons are in Byzantine style. Tradition has it that the icon showing the Virgin and Child was painted by St Luke.

Remember to remove shoes before entering either church and respect the silence and sanctity of the place. For a week every year (usually 21 to 28 June), thousands of pilgrims attend the monastery’s annual feast, a time when non-pilgrim visitors may not be admitted.

You will usually be escorted around the monastery and, while there is no fee, donations are appreciated. Visits sometimes finish with a brief visit to the new church built in 1940 or the nearby gift shop or, sometimes, with a cool drink in the monastery’s reception room.

The monastery is about 50 minutes’ drive from Asyut towards Minya. The bus will drop you at Al Qusiya, but currently you are not allowed to take a microbus, so you would have to walk. A taxi is the obvious alternative.

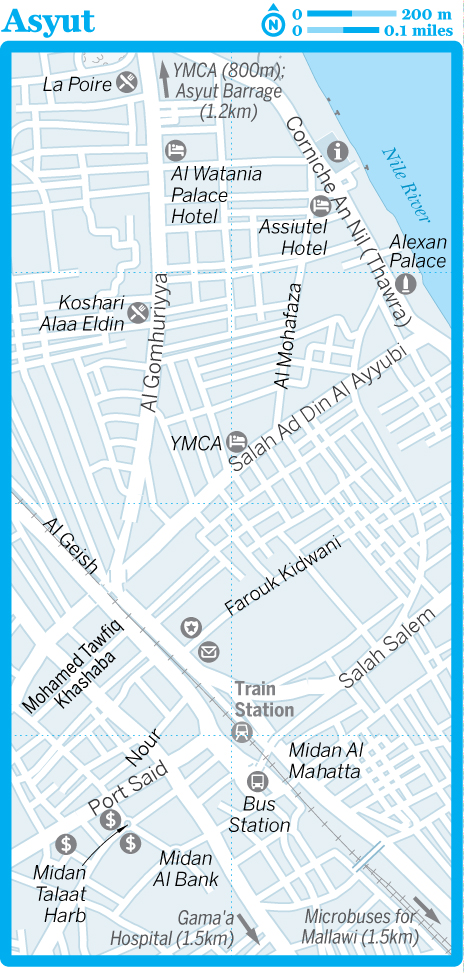

Asyut

![]() %088 / Pop 429,538

%088 / Pop 429,538

Asyut offers a very different view of Egypt than one might gain from Cairo or Luxor: it belongs to the provinces, a capital not of the country but of the area’s farming communities. Settled during Pharaonic times on a fertile plain west of the Nile, it has preserved an echo of antiquity in its name: as Swaty it was the ancient capital of the 13th nome of Upper Egypt. Sitting at the end of one of the great caravan routes from south of the Sahara via Sudan and then Al Kharga Oasis, it has always been important commercially, if not politically. For centuries, slaves were one of the main commodities traded here and caravans stopped to quarantine them before they were traded, a period in which slavers used to prepare some of their male slaves for the harem.

1Sights

For a city of such history, Asyut has surprisingly little to show for itself. In part, this is because much of what survives of ancient Asyut is either unexcavated or survives in the hills on the edge of the irrigation, which is currently off-limits to foreigners. Spiritual tourists did flock to Asyut in 2000 after the Virgin Mary was seen by both Copts and Muslims floating above the Church of St Mark. The apparitions continued for some months.

Asyut BarrageLandmark

Until the Nile-side Alexan Palace, one of the city’s finest 19th-century buildings, has been renovated and reopened, the Asyut Barrage serves as the most accessible introduction to Asyut’s period of wealth. Built over the Nile between 1898 and 1902 to regulate the flow of water into the Ibrahimiyya Canal and assure irrigation of the valley as far north as Beni Suef, it also serves as a bridge across the Nile.

As the barrage still has strategic importance, photography is forbidden, so you should keep your camera out of sight.

Banana IslandIsland

(Gezirat Al Moz)

Banana Island, to the north of town, is a shady, pleasant place to picnic. You’ll have to bargain with a felucca captain for the ride: expect to pay at least LE40 an hour.

Convent of the Holy VirginConvent

(![]() h6am-6pm)

h6am-6pm)

At Dirunka, some 11km southwest of Asyut, this convent was built near a cave where the Holy Family are said to have taken refuge during their flight into Egypt. Some 50 nuns and monks live at the convent, built into a cliff situated about 120m above the valley. One of the monks will be happy to show you around. You will need to go by taxi (LE60 to LE80).

During the Moulid of the Virgin (a festival held in the second half of August), many thousands of pilgrims come to pray, carrying portraits of Mary and Jesus.

4Sleeping

As a large provincial centre, Asyut has a selection of hotels, but many are overpriced and noisy. While prices have risen in the past few years, standards have not.

YMCAHostel$

(![]() %088-230-3018; Sharia Salah Ad Din Al Ayyubi; dm LE30;

%088-230-3018; Sharia Salah Ad Din Al Ayyubi; dm LE30; ![]() a)

a)

This hostel with a large garden offers basic rooms with fridges. A popular stop for Egyptian youth groups, make sure to book ahead.

Al Watania Palace HotelHotel$$

(![]() %088-228-7981; Sharia Al Gomhuriyya; s/d US$60/80;

%088-228-7981; Sharia Al Gomhuriyya; s/d US$60/80; ![]() a

a![]() W)

W)

The newest, smartest and largest hotel in Asyut is already looking a little worn. Part of a property development by a Gulf-backed consortium, it has an impressive lobby, spacious rooms, various function rooms and more stars than anywhere else in town. What you lose in location and atmosphere is made up for with comfort and service.

Assiutel HotelHotel$$

(![]() %088-231-2121; 146 Corniche An Nil (Thawra); s/d LE620/840;

%088-231-2121; 146 Corniche An Nil (Thawra); s/d LE620/840; ![]() a

a![]() i)

i)

Overlooking the Nile and the noisy corniche, this was once the best place in town, but it now looks drab. There are two levels of rooms, but neither are particularly welcoming and the cheaper ones are worn. All have satellite TV, fridge and private bathroom. There is a dull restaurant and one of Asyut’s only bars.

5Eating

The mid-priced rooftop restaurant at Al Watania Palace Hotel is among the more reliable places for a sit-down meal. There are several good fast food places along nearby Sharia Al Gomhuriyya. There are the usual fuul and ta’amiyya stands around the train station, and some more upmarket options along the Nile, where there is also a very friendly cafe.

![]() oKoshari Alaa EldinEgyptian$

oKoshari Alaa EldinEgyptian$

(Sharia Al Gomhuriyya; mains LE6-10; ![]() h10am-11pm)

h10am-11pm)

Excellent kushari from this friendly, simple place on one of the main streets in town.

La PoirePastries$$

(Sharia Al Gomhurriya; ![]() h10am-9pm Sat-Thu)

h10am-9pm Sat-Thu)

Excellent Egyptian and international pastries and ice cream in an offshoot of an upmarket Cairo patisserie. The kunafa (vermicelli-like pastry over a vanilla base soaked in syrup) with dates and almonds (LE110 a kilo) is particularly good.

8Information

There are ATMs at Midan Talaat Harb and along Sharia Port Said.

The very welcoming staff at the tourist office (![]() %088-231-0010; Governorate Bldg, Corniche An Nil (Thawra), which can look derelict when the doors are shut, can provide maps of the city and help arrange onward travel.

%088-231-0010; Governorate Bldg, Corniche An Nil (Thawra), which can look derelict when the doors are shut, can provide maps of the city and help arrange onward travel.

8Getting There & Away

Asyut is a major hub for all forms of transport, although if you want to go by road to Luxor and the south you will have to change at Sohag.

Bus

The Upper Egypt bus station (![]() %088-233-0460) near the train station has services to Cairo (LE80, five to six hours), Hurghada (LE80, 5½ hours), Sharm El Sheikh (LE130, 10 hours) and Alexandria (LE110, eight hours).

%088-233-0460) near the train station has services to Cairo (LE80, five to six hours), Hurghada (LE80, 5½ hours), Sharm El Sheikh (LE130, 10 hours) and Alexandria (LE110, eight hours).

Microbus & Taxi

There are no microbuses to Luxor. You might be able to take one to Mallawi, but this is sometimes forbidden. A private taxi to Luxor will cost up to LE1000.

Train

There are several daytime trains to Cairo (1st/2nd class LE79/44, four to five hours) and Minya (LE39/26, one hour), and about 10 daily south to Luxor (LE70/40, five to six hours) and Aswan (LE95/52, eight to nine hours). All stop in Sohag (LE33/21, one to two hours) and Qena (LE59/35, three to four hours).

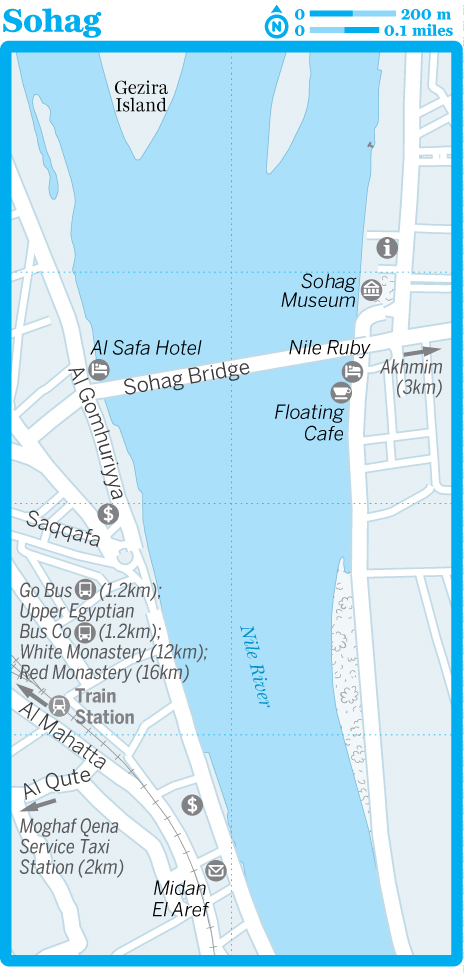

Sohag

![]() %093 / Pop 211,181

%093 / Pop 211,181

Sohag is one of the major Coptic Christian areas of Upper Egypt. Although there are few sights in the city, the nearby White and Red Monasteries are well worth a visit, and the town of Akhmim, across the river, is of interest.

1Sights

To get to the monasteries, you’ll have to take a taxi (about LE100 per hour).

![]() oRed MonasteryMonastery

oRed MonasteryMonastery

(Deir Al Ahmar; LE20; ![]() h7am-dusk)

h7am-dusk)

The Red Monastery, 4km southeast of the White Monastery and hidden at the rear of a village, is one of the most remarkable Christian buildings in Egypt. It was founded by Besa, a disciple of Shenouda who, according to legend, was a thief who converted to Christianity; he dedicated it to St Bishoi. Opening hours might be affected by services and Coptic holidays.

The older of the monastery’s two chapels, the Chapel of St Bishoi and St Bigol, dates from the 4th century AD and some 80% of its surfaces are still covered with painted plaster and frescoes, giving a good idea of how all late antique religious buildings might have looked. An extensive restoration by the American Research Center in Egypt and United States Agency for International Development (USAID) has revealed them in full glory. The quality and extent of the surviving work has led this chapel to be likened to the Aya Sofya in Istanbul and the church of Ravenna as one of the great surviving monuments of late antiquity. The chapel of the Virgin, across the open court, is a more modern and less interesting structure, but the services held here, with much incense, can be atmospheric.

White MonasteryMonastery

(Deir Al Abyad; LE20; ![]() h7am-dusk)

h7am-dusk)

On rocky ground above the old Nile flood level, 6km northwest of Sohag, the White Monastery was founded by St Shenouda around AD 400 and dedicated to his mentor, St Bigol. White limestone from Pharaonic temples was reused, and ancient gods and hieroglyphs still look out from some of the blocks. The design of the outer walls echoes ancient temples.

The monastery once supported a huge community of monks and boasted the largest library in Egypt. Research is finally underway on the manuscripts, while the monastery is currently home to 23 monks. The fortress walls still stand though they failed to protect the interior, most of which is in ruins. Nevertheless, it is easy to make out the plan of the church inside the enclosure walls. Made of brick and measuring 75m by 35m, it follows a basilica plan, with a nave, two side aisles and a triple apse. The nave and apses are intact, the domes decorated with the Dormition of the Virgin and Christ Pantocrator. Nineteen columns, taken from an earlier structure, separate the side chapels from the nave. Visitors wanting to assist in services may arrive from 4am.

AkhmimRuins

(Meret Amun; adult/child LE40/20)

The satellite town of Akhmim, on Sohag’s east bank, covers the ruins of the ancient Egyptian town of Ipu, itself built over an older predynastic settlement. It was dedicated to Min, a fertility god often represented by a giant phallus, equated with Pan by the Greeks (who later called the town Panopolis). A taxi to Akhmim should cost around LE50 per hour. The microbus, if you are allowed to take it, costs LE6 and takes 15 minutes.

The current name echoes that of the god Min, but more definite links to antiquity were uncovered in 1982 when excavations beside the Mosque of Sheikh Naqshadi revealed an 11m-high statue of Meret Amun. This is the tallest statue of an ancient queen to have been discovered in Egypt. Meret Amun (Beloved of the Amun) was the daughter of Ramses II, wife of Amenhotep and priestess of the Temple of Min. She is shown here with flail in her left hand, wearing a ceremonial headdress and large earrings. Nearby, the remains of a seated statue of her father still retain some original colour.

Little is left of the temple itself, and the statue of Meret Amun now stands in a small archaeological park, among the remains of a Roman settlement and houses of the modern town. Another excavation pit has been dug across the road and a more extensive excavation is underway nearby.

Akhmim was famed in antiquity for its textiles – one of its current weavers calls it ‘Manchester before history’. The tradition continues today and opposite the statue of Meret Amun, across from the post office, a green door leads to a small weaving factory (knock if it is shut). Here you can see weavers at work and buy hand-woven silk and cotton textiles straight from the bolt (silk LE200 per metre, cotton LE90 to LE125) or packets of ready-made tablecloths and serviettes.

Sohag MuseumMuseum

(adult/child LE60/30)

At the time of writing, the new Sohag Museum had not yet opened, but it will eventually display local antiquities, including those from ongoing excavations of the temple of Ramses II in Akhmim.

4Sleeping

Al Safa HotelHotel $

(![]() %093-230-7701, 093-230-7702; Sharia Al Gomhuriyya, west bank; s/d LE300/400;

%093-230-7701, 093-230-7702; Sharia Al Gomhuriyya, west bank; s/d LE300/400; ![]() a

a![]() W)

W)

This well-placed west-bank spot across the river from the new museum is the best hotel in town (which isn’t saying much). Rooms are comfortable and the riverside terrace is very popular in the evening for snacks, soft drinks and water pipes. Prices vary according to demand.

Nile RubyHouseboat$$

(![]() %012-2223-5440)

%012-2223-5440)

The downturn in Nile cruising has seen a number of boats converted to hotels, the latest being the Nile Ruby, moored near the bridge in Sohag. The boat was being cleaned up at the time of our last visit, and prices for the 70 cabins had not yet been fixed.

The King List

Ancient Egyptians constructed their history around their pharaohs. Instead of using a continuous year-by-year sequence, events were recorded as happening in a specific year of a specific ruler: at each pharaoh’s accession they started at year one, continuing until the pharaoh died, and then began again with year one of the next pharaoh.

The sequence of pharaohs was recorded on so-called king lists. These can be seen in the Egyptian Museum in Cairo, the Louvre in Paris and the British Museum in London. But the only one remaining in its original location can be found in Seti I’s Temple at Abydos. With an emphasis on the royal ancestors, Seti names 75 of his predecessors beginning with the semi-mythical Menes (usually regarded as Narmer). But the list is incomplete: Seti rewrites history by excluding pharaohs considered ‘unsuitable’, omitting the foreign Hyksos rulers of the Second Intermediate Period, the female pharaoh Hatshepsut and the Amarna pharaohs. So Amenhotep III is immediately followed by Horemheb, and in the process Akhenaten, Smenkhkare, Tutankhamun and Ay are simply erased from the record.

5Eating & Drinking

The best food options are in the two main hotels. Budget kushari, fuul and ta’amiyya places line the roads near the train station. For something more romantic, there is a cafe on Gezira Island, reached by boat from the north side of the Hotel Al Nil.

Floating CafeCafe

(![]() hnoon-midnight)

hnoon-midnight)

Moored on the west bank of the Nile, close to the bridge, this Nile-boat-turned-cafe looks tired, but still attracts crowds on a warm evening. There is a basic menu and sometimes a buffet, but avoid eating and stick to the nonalcoholic drinks. It can be a fun place to people-watch.

8Information

There are banks along Sharia Al Gomhuriyya.

The helpful tourist office (![]() %093-460-4913; Governorate Bldg;

%093-460-4913; Governorate Bldg; ![]() h8.30am-3pm Sun-Thu), in the building beside the museum on the east bank, can help arrange visits to the monasteries.

h8.30am-3pm Sun-Thu), in the building beside the museum on the east bank, can help arrange visits to the monasteries.

8Getting There & Away

Go Bus has a twice daily service to Cairo (LE135). The Upper Egyptian Bus Co has regular departures to Cairo between 7.30am and 9.30pm (LE85 to LE120).

There is a frequent train service north and south along the Cairo-Luxor main line, with a dozen daily trains to Asyut (1st/2nd class LE34/21, one to two hours) and Luxor (LE94/63, three to four hours). The service to Al Balyana (3rd class only, one to two hours) is very slow.

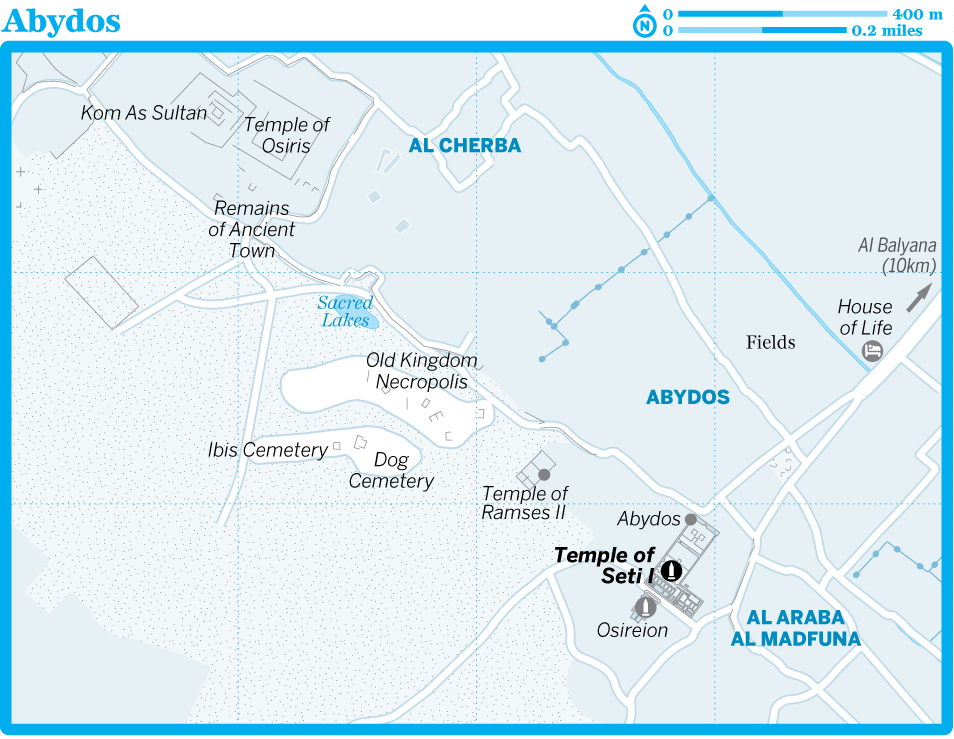

Abydos

There were shrines to Osiris, god of the dead, throughout Egypt, each one the supposed resting place of another part of his body, but the main cult centre of Osiris was Abydos (adult/student LE80/40; ![]() h8am-4pm). This was where his head was believed to rest and it became somewhere Egyptians tried to visit on pilgrimage during their lives and also the place to be buried: it was used as a necropolis for more than 4500 years from predynastic to Christian times (c 4000 BC–AD 600). Most tombs remain unexcavated, a fact reflected in the Arabic name for the place, Arabah El Madfunah (‘the buried Arabah’). The area behind the Temple of Seti I, known as Umm Al Qa’ab (Mother of Pots), contains the tombs of many early pharaohs including Djer (c 3000 BC) of the 1st dynasty. With excavations ongoing, this area is closed to the public.

h8am-4pm). This was where his head was believed to rest and it became somewhere Egyptians tried to visit on pilgrimage during their lives and also the place to be buried: it was used as a necropolis for more than 4500 years from predynastic to Christian times (c 4000 BC–AD 600). Most tombs remain unexcavated, a fact reflected in the Arabic name for the place, Arabah El Madfunah (‘the buried Arabah’). The area behind the Temple of Seti I, known as Umm Al Qa’ab (Mother of Pots), contains the tombs of many early pharaohs including Djer (c 3000 BC) of the 1st dynasty. With excavations ongoing, this area is closed to the public.

1Sights

![]() oTemple of Seti IMonument

oTemple of Seti IMonument

(Cenotaph; MAP GOOGLE MAP; adult/student LE80/40; ![]() h8am-4pm)

h8am-4pm)

The first structure you’ll see at Abydos is the Great Temple of Seti I, which, after a certain amount of restoration work, is one of the most complete, unique and beautiful temples in Egypt. With exquisite decoration and plenty of atmosphere, it is the main attraction here, although the nearby Osireion is also wrapped in mystery and the desert views are spectacular.

This great limestone structure, unusually L-shaped rather than rectangular, had seven great doorways and was dedicated to the six major gods – Osiris, Isis, Horus, Amun-Ra, Ra-Horakhty and Ptah – and also to Seti I (1294–1279 BC) himself. Less than 50 years after the end of the Amarna ‘heresy’ – when Pharaoh Akhenaten broke with tradition by creating a new religion, capital and artistic style – this is a clear attempt to revive the old ways. As you roam through Seti’s dark halls and sanctuaries, an air of mystery surrounds you.

The temple is entered through a largely destroyed pylon and two open courtyards, built by Seti I’s son Ramses II, who is depicted on the portico killing Asiatics and worshipping Osiris. Beyond, originally with seven doorways but now only entered through the central one, is the first hypostyle hall, also completed by Ramses II. Reliefs depict the pharaoh making offerings to the gods and preparing the temple building.

The second hypostyle hall, with 24 sandstone papyrus columns, was the last part of the temple to have been decorated by Seti, who died before the work was completed. The reliefs here are of the highest quality and hark back to the finest Old Kingdom work. Particularly outstanding is a scene on the rear right-hand wall showing Seti standing in front of a shrine to Osiris, upon which sits the god himself. Standing in front of him are the goddesses Maat, Renpet, Isis, Nephthys and Amentet. Below is a frieze of Hapi, the Nile god.

At the rear of this second hypostyle hall are sanctuaries for each of the seven gods (right to left: Horus, Isis, Osiris, Amun-Ra, Ra-Horakhty, Ptah and the deified Seti), which once held their cult statues. The Osiris sanctuary, third from the right, leads to a series of inner chambers dedicated to the god, his wife and child, Isis and Horus, and the ever-present Seti. More interesting are the chambers off to the left of the seven sanctuaries: here, in a group of chambers dedicated to the mysteries of Osiris, the god is shown mummified with the goddess Isis hovering above him as a bird, a graphic scene which records the conception of their son Horus.

Immediately to the left of this is the corridor known as Gallery of the Kings, carved with the figures of Seti I, his eldest son the future Ramses II, and a long list of the pharaohs who preceded them. The stairway leads out to the Osireion and the desert beyond.

One of the temple’s most recent residents was Dorothy Eady. An Englishwoman better known as ‘Omm Sety’, Eady believed she was a reincarnated temple priestess and lover of Seti I. For 35 years she lived at Abydos and provided archaeologists with information about the workings of the temple, in which she was given permission to perform the ancient rites. She died in 1981 and is buried in the desert.

OsireionMonument

Directly behind the Temple of Seti I, the Osireion is a weird and wonderful structure, unique in Egypt and still baffling for Egyptologists. The entire structure is closed to visitors, making inspection of the funerary and ritual texts carved on its walls impossible, but you can look down on it from the rear of Seti’s temple, from where there is a good overview of the cenotaph and its surrounding waters.

Originally thought to be an Old Kingdom construction, on account of the great blocks of granite, it has now been dated to Seti’s reign and is usually interpreted as a cenotaph to Osiris, or more specifically to Seti as Osiris. Its design is believed to be based on the rock-cut tombs in the Valley of the Kings. Reached by a 420-ft subterranean passage, the centre of its 10-columned ‘burial chamber’, which lies at a lower level than Seti’s temple, is a dummy sarcophagus. This chamber is surrounded by water channels to simulate an island.

Temple of Ramses IITemple

Northwest of Seti I’s temple, this smaller, less well-preserved, roofless structure was built by his son Ramses II (1279–1213 BC). Following the rectangular plan of a traditional temple, it has sanctuaries for each god Ramses considered important, including Osiris, Amun-Ra, Thoth, Min, the deified Seti I and Ramses himself. The reliefs still retain a significant amount of colour, clearly seen on figures of priests, offering bearers and the pharaoh anointing the gods’ statues. The site is occasionally placed off-limits.

4Sleeping

House of LifeHotel$$

(![]() %010-1000-8912, 093-494-4044; www.houseoflife.info; s/d €55/70;

%010-1000-8912, 093-494-4044; www.houseoflife.info; s/d €55/70; ![]() a

a![]() i

i![]() W

W![]() s)

s)

This large Dutch-Egyptian-run complex with a mock-Pharaonic facade is on the road leading to the Temple of Seti I. Spacious, quiet and well-equipped rooms have walk-in showers. Most look onto the swimming pool or surrounding countryside (no temple views). There is a healing centre using ancient remedies and an outdoor cafe serving soft drinks and water pipes.

8Getting There & Away

Al Araba Al Madfuna is 10km from the nearest train station, at Al Balyana. Most people arrive from Luxor, where many companies offer day-long coach tours. A private taxi from Luxor will cost from LE900 return, depending on bargaining skills and how long you want at the temple. A train leaves Luxor at 8.25am (1st/2nd class LE52/42, three hours). A private taxi from Al Balyana to the temple will cost about LE60 depending on the wait time. A microbus from Al Balyana costs LE3.

Qena

![]() %096 / Pop 257,939

%096 / Pop 257,939

Qena sits on a huge bend of the river, and at the intersection of one of the main Nile roads and the road running across the desert to the Red Sea port of Port Safaga and resort town of Hurghada. A market town and provincial capital, it is a useful junction for a visit to the nearby spectacular temple complex at Dendara. It’s also the place to be on the 14th of the Islamic month of Sha’ban, when the city’s 12th-century patron saint, Abdel Rehim Al Qenawi, is celebrated.

1Sights

![]() oDendaraTemple

oDendaraTemple

(adult/student LE80/40; ![]() h7am-6pm)

h7am-6pm)

Dendara was an important administrative and religious centre as early as the 6th dynasty (c 2320 BC). Although built at the very end of the Pharaonic period, the Temple of Hathor is one of the iconic Egyptian buildings, mostly because it remains largely intact, with a great stone roof and columns, dark chambers, underground crypts and twisting stairways, all carved with hieroglyphs.

All visitors must pass through the visitors centre with its ticket office and bazaar. While it is still mostly unoccupied, before long this may involve running the gauntlet of hassling traders to get to the temple. One advantage is a clean, working toilet. At the time of our visit, it was not possible to buy food or drinks at the site.

Beyond the towering gateway and mud walls, the temple was built on a slight rise. The entrance leads into the outer hypostyle hall, built by Roman emperor Tiberius, the first six of its 24 great stone columns adorned on all four sides with Hathor’s head, defaced by Christians but still an impressive sight. The walls are carved with scenes of Tiberius and his Roman successors presenting offerings to the Egyptian gods: the message here, as throughout the temple, is the continuity of tradition, even under foreign rulers. The ceiling at the far left and right side of the hall is decorated with zodiacs. One section has now been cleaned and the colours are very bright.

The inner temple was built by the Ptolemies. The smaller inner hypostyle hall again has Hathor columns and walls carved with scenes of royal ceremonials, including the founding of the temple. But notice the ‘blank’ cartouches that reveal much about the political instability of late Ptolemaic times – with such a rapid turnover of pharaohs, the stonemasons seem to have been reluctant to carve the names of those who might not be in the job for long. Things reached an all-time low in 80 BC when Ptolemy XI murdered his more popular wife and stepmother Berenice III after only 19 days of co-rule. The outraged citizens of Alexandria dragged the pharaoh from his palace and killed him in revenge.

Beyond the second hypostyle hall, you will find the Hall of Offerings leads to the sanctuary, the most holy part of the temple, home to the goddess’ statue. A further Hathor statue was stored in the crypt beneath her temple, and brought out each year for the New Year Festival, which in ancient times fell in July and coincided with the rising of the Nile. It was carried into the Hall of Offerings, where it rested with statues of other gods before being taken to the roof. The western staircase is decorated with scenes from this procession. In the open-air kiosk on the southwestern corner of the roof, the gods awaited the first reviving rays of the sun-god Ra on New Year’s Day. The statues were later taken down the eastern staircase, which is also decorated with this scene.

The theme of revival continues in two suites of rooms on the roof, decorated with scenes of the revival of Osiris by his sister-wife, Isis. In the centre of the ceiling of the northeastern suite is a plaster cast of the famous ‘Dendara Zodiac’, the original now in the Louvre in Paris. Views of the surrounding countryside from the roof are magnificent.

The exterior walls feature lion-headed gargoyles to cope with the very occasional rainfall and are decorated with scenes of pharaohs paying homage to the gods. The most famous of these is on the rear (south) wall, where Cleopatra stands with Caesarion, her son by Julius Caesar.

Facing this back wall is a small temple of Isis built by Cleopatra’s great rival Octavian (the Emperor Augustus). Walking back towards the front of the Hathor temple on the west side, the palm-filled Sacred Lake supplied the temple’s water. Beyond this, to the north, lie the mudbrick foundations of the sanatorium, where the ill came to seek a cure from the goddess.

Finally there are two mammisi (birth houses): the first was built by the 30th-dynasty Egyptian pharaoh, Nectanebo I (380–362 BC), and decorated by the Ptolemies; the other was built by the Romans and decorated by Emperor Trajan (AD 98–117). Such buildings celebrated divine birth, both of the young gods and the pharaoh himself as the son of the gods. Between the mammisi lie the remains of a 5th-century-AD Coptic basilica.

Dendara is 4km southwest of Qena on the west side of the Nile. Most visitors arrive from Luxor. A return taxi from Luxor will cost you about LE200. There is also a day cruise to Dendara from Luxor. If you arrive in Qena by train, you will need to take a taxi to the temple (LE40 to the temple and back with some waiting time).

8Getting There & Away

Bus

The Upper Egypt Bus Co (Midan Al Mahatta), at the bus station opposite the train station, runs regular services to Cairo via the Red Sea, Hurghada and Suez.

Microbus

At the time of writing, foreigners were not allowed to use microbus services. When this changes, from the station, 1km inland from the bridge, you will be able to get south to Luxor and Aswan, east to Hurghada, Marsa Alam and Suez, and north to Nag Hamadi, Sohag and Asyut.

Train

All main north–south trains stop at Qena. There are 1st-/2nd-class air-con trains to Luxor (from LE27/19, 40 minutes) and trains to Al Balyana (2nd/3rd class LE18/12, two hours).