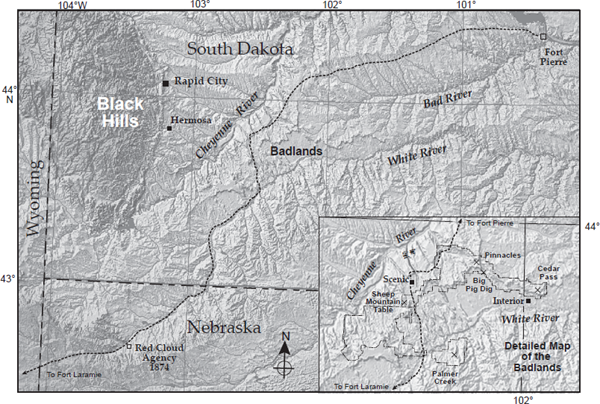

1.1. Regional map of southwest South Dakota and adjacent states showing the features related to the history of the geologic and paleontologic studies of the Big Badlands. The dashed line indicates the route of the Fort Pierre–Fort Laramie road, plotted after the map of Warren (1856). The inset map of the details of the Badlands area includes the boundaries of the three units of present Badlands National Park (dash–dot lines). The base map is from the U.S. National Atlas Web site (http://nationalatlas.gov/mapmaker).

THE FIRST FOSSILS FROM THE BADLANDS OF SOUTH Dakota were collected by employees of the American Fur Company and sent to scientists in the eastern United States. The fur company had opened up a wagon road between Fort Pierre on the Missouri River and Fort John, later known as Fort Laramie, on the Platte River (Fig. 1.1). This was a much shorter route from the Missouri than the long Platte River road, and it crossed the Big Badlands in the headwaters of Bear Creek near the modern town of Scenic, then went south on the east side of Sheep Mountain Table to the White River. Various fur company employees may have collected fossils from this area in the 1840s, but it was the chief agent of the upper Missouri posts for the fur company, Alexander Culbertson, who sent fossils to St. Louis and to his father and uncle in Pennsylvania. Dr. Hiram Prout of St. Louis had been sent a lower jaw fragment of a huge mammal that he identified as Palaeotherium because of its similarity to figured specimens of this European fossil mammal. He sent a cast of this specimen and a letter to Yale University in 1846. The letter and a crude drawing of the specimen’s teeth were published in 1846. Prout described the specimen in greater detail the following year, 1847, and this became the first White River fossil mammal to be described in the scientific literature (Fig. 1.2A). The other fossils sent to Culbertson’s father and uncle eventually made their way to Dr. Joseph Leidy of the Philadelphia Academy of Sciences (Fig. 1.3). One of Leidy’s many academic talents was vertebrate paleontology, and beginning with the description of the first fossil camel skull found in the United States, which he named Poebrotherium in 1847 (Fig. 1.2B), he started a long career as the preeminent vertebrate paleontologist of the United States.

These first publications on the fossils from the Badlands piqued the interest of geologists and naturalists, some of whom eventually visited the Badlands. Among these was Dr. David Dale Owen, who was making a geologic survey of Wisconsin, Minnesota, and Iowa. In 1849 Owen sent one of his assistant geologists, Dr. John Evans, to the Badlands to collect fossils and to determine the age relations of the fossil-bearing rocks. Evans and his field party spent about a week in the Badlands, and all the fossils were sent to Leidy. The results of Evan’s expedition plus descriptions of the vertebrate fossils by Leidy were published in 1852. This report included the first map of the region (Fig. 1.4) and the first diagram of the Badlands (Fig. 1.5). Evans described the Badlands as follows:

To the surrounding country . . . the Mauvaises Terres present the most striking contrast. From the uniform, monotonous, open prairie, the traveler suddenly descends, one or two hundred feet, into a valley that looks as if it had sunk away from the surrounding world; leaving standing, all over it, thousands of abrupt, irregular, prismatic, and columnar masses, frequently capped with irregular pyramids, and stretching up to a height of from one to two hundred feet, or more.

So thickly are these natural towers studded over the surface of this extraordinary region, that the traveler threads his way through deep, confined, labyrinthine passages, not unlike the narrow, irregular streets and lanes of some quaint old town of the European Continent. Viewed in the distance, indeed, these rocky piles, in their endless succession, assume the appearance of massive artificial structures, decked out with all the accessories of buttress and turret, arched doorway and clustered shaft, pinnacle, and finial, and tapering spire. (Evans, 1852:197)

Thaddeus A. Culbertson was the younger half-brother of Alexander Culbertson and was educated at what is now Princeton University. He decided to travel in the summer of 1850 to the upper Missouri country to study the Native Americans along the river and to collect natural history specimens. He discussed his trip with Spencer F. Baird, who was soon to become a curator at the Smithsonian Institution. Baird urged the younger Culbertson to make a visit to the Badlands to collect fossil vertebrates. Culbertson traveled with two guides to the upper Bear Creek drainage and spent about a day collecting. He returned to Fort Pierre with a small but good collection of fossils. Culbertson returned to Washington in August 1850 but died 3 weeks after his return from complications related to tuberculosis. Baird had some of Culbertson’s journal of the trip published in 1851, but Culbertson’s entire journal was not completely published until 1952 by McDermott. All of the fossils that Evans and the Culbertson brothers collected were sent to Leidy, who published his first monograph on the Mauvaises Terres fauna in 1853.

1.2. Illustrations of the first two fossils described from the Big Badlands. (A) Diagram of “gigantic Palaeotherium” jaw published in Prout (1847). (B) Type specimen of Poebrotherium wilsoni published by Leidy (1847). This diagram is from Leidy (1853:plate 1, fig. 1). All early diagrams of White River fossils were made from specimens, not from reconstructed complete skulls and jaws.

Eighteen fifty-three was the year not only of Leidy’s first monograph but also of the second trip of Evans to the Badlands, and the first trip to the Badlands by Fielding B. Meek and Ferdinand V. Hayden (Fig. 1.3). Meek became the preeminent invertebrate paleontologist in the United States, specializing in the invertebrate fossils of the west, and Hayden would later become the director of one of the five great geologic surveys of the American West after the Civil War. In 1853 both were assistants of James Hall of the New York Geological Survey. Hall wanted collections from the upper Missouri basin, including fossils from the Badlands. Sent by Hall to St. Louis, Meek and Hayden initially met opposition to their proposed collecting trip to the Badlands by Evans, who considered the two to be interlopers in the fossil beds. However, the two groups finally cooperated and spent about a month collecting along the Fort Pierre–Fort Laramie road (Fig. 1.6). Hayden would return to the Badlands in May 1855, traveling along buffalo trails along the south side of the White River, and collecting at such areas as the Palmer Creek area of the modern South Unit of Badlands National Park (Hayden, 1856). Hayden served for the Union army as a surgeon during the Civil War, and after the war he would make one last trip to the Badlands. In May 1866 Hayden traveled from Fort Randall along the Missouri River up the Niobrara River, across the Pine Ridge, to his old fossil-collecting areas at Palmer Creek, the south end of Sheep Mountain Table, and the upper Bear Creek drainage. Hayden (1869) was disappointed in the relatively small numbers of fossils that he found in the areas that he had collected in 1853 and 1855. Apparently there had not been enough erosion to uncover fossils in the numbers that he had found in his earlier surveys. In 1869 Hayden wrote the geology discussion to Leidy’s great monograph, The Extinct Mammalian Fauna of Dakota and Nebraska. This monograph summarized all of the fossil mammals from the White River Group (named as the White River Series by Meek and Hayden in 1858) that had been collected over the previous two decades (Fig. 1.7). This work would be the best description of White River fossils for the next 70 years.

1.3. Some of the important early paleontologists who worked in the Badlands. Joseph Leidy worked at the Philadelphia Academy of Sciences and was the first to publish a monograph of the fossils from the Big Badlands. Fielding B. Meek and Ferdinand V. Hayden collected in the Badlands in 1853 and named the White River Group in 1859. John Bell Hatcher worked as a collector for O. C. Marsh at Yale and later taught at Princeton University.

1.4. Details of the Evans map compiled in 1849 showing the route to the Badlands, published in Evans (1852). The perspective on this map is to the west, as if one were traveling to the Badlands from Fort Pierre. The road from Fort Pierre to Fort Laramie is plotted with the thin dashed line (cf. Fig. 1.1).

Collecting parties from East Coast universities and museums dominated the studies of the Badlands in the late nineteenth century and first half of the twentieth century. Othniel C. Marsh of the Yale Peabody Museum collected in the White River Badlands in 1874 (Schuchert and LeVene, 1940). Marsh collected primarily in northwest Nebraska, though he may have made excursions as far north as the South Dakota Badlands. While at the Red Cloud Agency, Marsh learned of the following Lakota tale from a friend, Captain James H. Cook. Cook had been shown a huge molar from a brontothere by the Lakota, and Cook’s friend, American Horse, told the following legend about the beast:

American Horse explained that the tooth had belonged to a “Thunder Horse” that had lived “away back” and that then this creature would sometimes come down to earth in thunderstorms and chase and kill buffalo. His old people told stories of how on one occasion many, many years back, this big Thunder Horse had driven a herd of buffalo right into a camp of Lacota [sic] people during a bad thunderstorm, when these people were about to starve, and that they had killed many of these buffalo with their lances and arrows. The “Great Spirit” had sent the Thunder Horse to help them get food when it was needed most badly. This story was handed down from the time when the Indians had no horses. (Osborn, 1929:xxi)

1.5. First image of the topography of the Badlands, published in the Evans report (1852:196). The image was made from a sketch by Eugene de Girardin, the artist on the Evans expedition. De Girardin’s sketches reproduced the topographic features of the Badlands quite well, but somehow the badland slopes and cliffs became translated by the engraver into a series of vertical pillars not seen in the Badlands.

Not long after, Marsh named one of the genera of these huge relatives of the rhinoceros Brontotherium, “thunder beast.” Though this genus name is not widely used today, the group is still referred to as brontotheres.

After 1874 Marsh hired collectors to send him fossils from the West. The most capable and renowned of these collectors was John Bell Hatcher (Fig. 1.3). In 1886 Marsh sent Hatcher out to the Great Plains to collect skulls and skeletons of brontotheres that occur in the lower deposits of the White River Group. Hatcher started his work in northwest Nebraska and adjacent Wyoming, but in 1887 he traveled to the Badlands east of Hermosa, South Dakota, where he collected 13 skulls, including three skulls in a single day. In the 15 months that he collected brontothere fossils during the three field seasons of 1886, 1887, and 1888, Hatcher collected 105 skulls and numerous skeletons and isolated bones of brontotheres (Hatcher, 1893:214) that totaled about 24.5 tons of fossil materials (estimated from the figures given in Schuchert and LeVene, 1940). No other collector of White River fossils has matched the volume of materials collected by Hatcher.

Between 1890 and 1910 many major museums and universities sent collecting parties to the Badlands. These included the American Museum of Natural History in New York; the Carnegie Museum in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania; the Field Museum of Natural History in Chicago; Princeton University; Amherst College in Massachusetts; the University of Nebraska in Lincoln; the University of Kansas in Lawrence; the University of South Dakota in Vermillion; and the South Dakota School of Mines (O’Harra, 1910). Meek and Hayden (1858) had given the name White River Series to the rocks of the South Dakota Badlands, and they subdivided the rocks by their fauna into the lower titanothere beds and the overlying turtle–Oreodon beds. Jacob L. Wortman, while working in the South Dakota Badlands in 1892 as a collector for the American Museum of Natural History, recognized an additional faunal subdivision for the White River (Wortman, 1893). He subdivided Hayden’s turtle–Oreodon beds into the lower Oreodon beds (dominated by the oreodont Merycoidodon) with the Metamynodon channels and the upper Leptauchenia beds (another kind of oreodont) with the Protoceras channels. Metamynodon is a large, primitive, odd-toed ungulate (perissodactyl) related to the rhinoceros, and Protoceras is a medium-size, even-toed ungulate (artiodactyl) that is a member of an extinct group related to the camels and deer. This three-part faunal division of the White River sequence was later formalized as the Chadronian, Orellan, and Whitneyan land mammal ages (Wood et al., 1941). The first subdivisions of the White River rocks on the basis of rock types (lithology) was made by N. H. Darton (1899) of the U.S. Geological Survey, who recognized the lower Chadron Formation as well as the upper Brule Formation in western Nebraska and South Dakota. The Chadron Formation included the basal red beds and the overlying greenish-gray claystone beds of the lower White River, while the Brule Formation included the tan mudstone and siltstone beds of the upper White River. Together, the Chadron and Brule formations make up the White River Group of South Dakota and Nebraska.

1.6. Fielding B. Meek’s sketch of the Badlands made in 1853 and published in Hayden’s geology report in Leidy’s 1869 monograph. The area shown is of the large buttes near the modern access road to Sheep Mountain Table.

Paleontologists could position their fossil localities to within these broad faunal subdivisions, but the lack of detailed maps in the 1800s prevented the detailed recording of geographic locations of fossil sites, and only rudimentary sedimentology concepts were understood. Evans (1852), Hayden (1869), and most nineteenth-century geologists thought the White River sediments had been deposited in a huge lake. Fine-grained, fairly well-bedded rocks were thought to have been deposited in quiet water, and the presence of freshwater snails and clams were used as evidence of the existence of a lake that covered a huge area of the Great Plains and butted up against the flanks of the Black Hills and Rocky Mountains. The bones of mammals and other land-dwelling organisms were thought to have washed into the lake from rivers during floods. This so-called lacustrine theory for the origin of the White River and other Tertiary rocks of the Great Plains was questioned as early as 1869 by Leidy, who found few aquatic vertebrates in the White River fossil record to support the existence of the lake. The lacustrine theory was finally debunked by Hatcher in 1902. Hatcher made his argument that the White River rocks were deposited by rivers because of the presence of ancient river channels represented by long, thin, sinuous gravel and coarse sand deposits scattered throughout the White River fine-grained mudrocks. The White River fauna included almost all land-dwelling organisms, along with extremely few aquatic vertebrates and invertebrates except in channel deposits or the thin limestone deposits. The few plant fossils (hackberry seeds, fossil roots, and rare tree stumps) also were widely distributed in the White River mudrocks. Because of his arguments and professional stature as a well-respected vertebrate paleontologist, Hatcher put the lacustrine theory to rest.

1.7. A diagram of a complete skull of Oreodon culbertsoni, published by Leidy (1869:plate 6, fig. 1). By 1869 enough complete skulls were available for complete reconstructions of some White River mammals.

For six decades, paleontologists and geologists from Princeton University made extensive studies of the rocks and fossils from the South Dakota Badlands. William Berryman Scott led the first Princeton students into the Badlands in 1882. While publishing extensively on the White River mammals, he returned with students to the area in 1890 and 1893. John Bell Hatcher had been hired as a curator of vertebrate paleontology by Princeton in 1893, and he joined Scott and the students in the Badlands that summer. Scott turned the student field camp duties over to Hatcher, who made many more extensive collections for Princeton. Hatcher left Princeton in 1900, and in 1905 Dr. William J. Sinclair was hired as vertebrate paleontologist. In 1920 he started a major study of the fossils and geology of the lowest beds of the Brule Formation in the Badlands, then called the red layer. Sinclair was not only an excellent vertebrate paleontologist but also an excellent geologist. Sinclair (1923) was one of the first to consider the detailed origins of the White River bone beds on the basis of the lithologic context and postmortem (taphonomic) features of the fossil bones. He carefully recorded the vertical positions of the fossils within the lower Brule Formation and documented vertical changes in the faunas. Sinclair’s first student, Harold R. Wanless, made one of the most extensive studies of the White River rocks in the South Dakota Badlands. Wanless (1921) studied the lithologic features of the White River Group and the distribution and origin of the rocks over a large area, mainly west of Sheep Mountain Table (Wanless, 1923). Wanless carefully recorded his observations and interpretations and his papers are still essential reading for anyone who studies the geology of the Badlands. Sinclair was to work with William Berryman Scott on a monographic study of the White River fauna, but Sinclair died in 1935. Sinclair’s student Glenn L. Jepsen took over as Scott’s colleague in the monumental monograph The Mammalian Fauna of the White River Oligocene, published between 1936 and 1941. The well-illustrated five-part set (Fig. 1.8) was divided into the following taxonomic groups; insectivores and carnivores (Scott and Jepsen, 1936), rodents (Wood, 1937), lagomorphs (Wood, 1940), artiodactyls (Scott and Jepsen, 1940), and perissodactyls, edentates and marsupials (Scott, 1941). This was the first extensive White River monograph since Leidy (1869) and has never been duplicated.

Jepsen took over as the vertebrate paleontologist at Princeton but his interest drifted into older Paleogene faunas, ending White River studies at Princeton. His student John Clark continued the work on the White River Group from the 1930s well into the 1970s. Clark’s doctoral dissertation, published in 1937, was on the geology and paleontology of the Chadron Formation in the South Dakota Badlands. Similar in methods to those of Sinclair and Wanless, Clark also made analyses of the vertebrate fauna of the Chadron formation. Working primarily for the Carnegie Museum of Natural History in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, and later at the Field Museum of Natural History in Chicago, Clark continued his studies of the Chadron Formation and expanded into studying the lower Brule Formation (Scenic Member). Clark (1954) gave names to the three parts of the Chadron Formation west of Sheep Mountain Table: the Ahearn, Crazy Johnson, and Peanut Peak members. After 30 years of study, Clark and two contributors, James R. Beerbower and Kenneth K. Kietzke, published a memoir in 1967 about their work in White River rocks and faunas of the Badlands titled Oligocene Sedimentation, Stratigraphy, Paleoecology, and Paleoclimatology in the Big Badlands of South Dakota. This memoir discusses such topics as paleoclimatology as interpreted from the rocks and fauna, paleoecology from the distribution of the fauna in the rocks and the rocks’ depositional environments, and details of fluvial sedimentology. These discussions predated modern detailed sedimentologic and faunal analyses by decades.

The school with the longest continual record of study of the White River rocks and fossils in the Badlands is the South Dakota School of Mines and Technology in Rapid City. Cleophas C. O’Harra was the first School of Mines geology professor to take students into the Badlands, primarily for geologic studies and secondarily to collect fossils. His first trip was in 1899 to the Sheep Mountain Table area, and O’Harra continued to take students on yearly trips to the Badlands for the next two decades. In 1920 O’Harra wrote a popular guide to the geology and paleontology of the Badlands and surrounding areas that is still available in print and has served as a model for this volume. In 1924 Glenn Jepsen, then an instructor at the School of Mines organized the first trip to solely collect vertebrate fossils in the Badlands for the School of Mines Museum. When Jepsen left for his studies at Princeton, James D. Bump took over the role of paleontologist, becoming the director of the museum in 1930. In 1940 Bump and other faculty at the School of Mines were awarded a grant from the National Geographic Society to collect exhibit-quality White River fossils for the Museum. Bump and his crew spent 3 months collecting in the upper Brule rocks in the Palmer Creek area, which is now in the South Unit of Badlands National Park. These fossils became the basis of exhibits in the new museum hall in the O’Harra Building that was completed in 1944, though the final exhibits were constructed through the 1960s. The exhibits of White River fossil vertebrates are still on display in this building and include some of the finest White River mammal skeleton reconstructions in the nation. In 1956 Bump formally named the two members of the Brule Formation, the Scenic Member of the lower Brule Formation and the Poleslide Member of the upper Brule Formation, and designated type sections near the town of Scenic and on the south side of Sheep Mountain Table, respectively. The rocks that overlie the Brule Formation were named and described as the Sharps Formation in 1961 by J. C. Harksen, J. R. Macdonald, and W. D. Sevon, all from the School of Mines. Macdonald had been hired as the first vertebrate paleontology curator for the school in 1949. The volcanic tuff on the top of the Brule Formation, the Rockyford “Ash,” was named and described by a J. M. Nicknish and J. R. Macdonald in 1962. Later, paleontologists from the School of Mines Museum, Robert W. Wilson and Philip R. Bjork, worked extensively in the Badlands during the 1960s through the 1980s. Dr. Bjork was especially active in collecting White River fossils from the upper Brule Formation (the Poleslide Member) in the Cedar Pass and Palmer Creek areas of Badlands National Park. To date, there have been eight completed Master’s theses on geology and 18 theses on paleontology of the Badlands at the School of Mines. As a result of this research, the South Dakota School of Mines Museum has perhaps the largest collection of fossil vertebrates from the Badlands in the United States. As a partner repository with Badlands National Park it is the primary repository for the fossils collected in the park and surrounding areas.

1.8. Diagrams of the skulls of Poebrotherium wilsoni and Merycoidodon culbertsoni by the artist R. Bruce Hornsfall. These were made for part 4 of the Artiodactyla of the Mammalian Fauna of the White River Oligocene monograph by Scott and Jepsen (1940:plate 64, fig. 1, and plate 69, fig. 1). Almost all the diagrams in the Scott and Jepsen monographs are reconstructions based on complete skeletons, skulls, and bones from the vast collections of White River vertebrates amassed by the mid-twentieth century. Compare these with the original images of the type specimen of Poebrotherium (Fig. 1.2B) and the first reconstruction of the skull of Oreodon (Fig. 1.7).

During the 1980s, new methods were developed to analyze the rocks of the White River Group. One such technique is the analysis of ancient soils (or paleosols). Sedimentary rocks are typically described by lithology in depositional packages. Terrestrial sedimentary rocks deposited by rivers or as dust deposits (eolian sediments) are greatly modified by weathering and the action of soil organisms (plants and animals) to form soils. The remains of these soil processes are preserved in the rock, and require detailed analysis. In 1983 Dr. Greg J. Retallack of the University of Oregon described in great detail the ancient soil features of White River rocks in the upper Conata basin and Pinnacles area of Badlands National Park. From these data Retallack related the ancient soils to modern soil types that form under specific climatic and depositional environments (Fig. 1.9). He documented changes through time in the vegetation and climate as recorded in the White River Group in a single section located south of the Pinnacles Overlook. His report, published in 1983, was a landmark study showing the potential of paleosol studies for detailed paleoenvironmental interpretations. Retallack’s study was the predecessor to the work of Dr. Dennis O. Terry Jr. and his students from Temple University, Philadelphia, who have studied many additional paleosol sequences in the Badlands throughout the North Unit of Badlands National Park (see the discussion in chapter 3). Terry, along with Dr. James E. Evans, proposed in 1994 a new formation at the base of the White River Group, the Chamberlain Pass Formation.

1.9. Reconstruction of ancient environments during the deposition of the Scenic Member made by Retallack (1983a:fig. 7). The Zisa, Gleska, and Conata series are types of ancient buried soils that were formed in active channels, heavily forested river riparian (near channels), and open distal overbank (far from channels) environments.

Another advanced technique of studying the White River rocks is the study of the ancient magnetic signals in the rocks, called paleomagnetism analysis. This technique measures in rocks the magnetic orientation of tiny magnetic minerals. These magnetic minerals record the properties of the Earth’s magnetic field at the time the rock was formed. The dynamics of the Earth’s magnetic field will sometimes allow the magnetic poles to switch position. This switching occurs relatively quickly relative to geologic time and its effects are global. The times when the Earth’s magnetic field has switched have been calibrated by radiometric dates, so the changes in the paleomagnetic signals in rocks give us a proxy for time. Donald R. Prothero, emeritus of Occidental College in Los Angeles, is a pioneer in the study of paleomagnetism of Cenozoic sedimentary rocks in the western United States. He has analyzed the paleomagnetism of the White River rocks in the Badlands and has published a series of publications on this paleomagnetic record (Prothero, 1985; Tedford et al., 1996; Prothero and Whittlesey, 1998).

The Big Badlands were first protected in 1939 by the establishment of Badlands National Monument. The Monument included what is now known as the North Unit, but in 1978 Badlands became a national park with the inclusion of 130,000 acres of lands to the south that was to be jointly administered by the National Park Service and the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation. This southern addition is now the South Unit of Badlands National Park. In 1994 the National Park Service hired Rachel C. Benton as the first park paleontologist for Badlands National Park. Dr. Benton has developed an extensive paleontological resource management program that has included locating, surveying, and monitoring fossil localities; evaluating and permitting proposed geological and paleontological research projects in Badlands National Park; evaluating and recording new fossil sites discovered by researchers and visitors to the park; and overseeing monitoring of fossil resources that are uncovered during construction projects in the park. To do all of this work, Dr. Benton oversees as many as 12 seasonal employees and interns each summer. She is also involved with public education, teaching seasonal interpreters about the fossils of Badlands; overseeing new additions to the exhibits in the Ben Reifel Visitor Center; opening and maintaining quarries so visitors can see fossil excavations in progress; and establishing and overseeing a fossil preparation laboratory in the Ben Reifel Visitor Center that has been open for public viewing.

One of the most popular visitor attraction and a major scientific study organized by Dr. Benton was the development and excavation of the Big Pig Dig. This is a bone bed situated near the Conata Picnic Ground that contained a large number of fossil bones and skulls, primarily of the large piglike entelodont Archaeotherium, and the rhinoceros, Subhyracodon. The site was discovered in 1993 and was excavated for 15 field seasons. Over 19,000 bones, teeth, and skulls were excavated from the site and are now stored at the Museum of Geology at the South Dakota School of Mines and Technology. The site was open to the public as it was excavated by SDSM seasonal paleontologists, students, and interns, and it was visited by between 5000 and 10,000 visitors per year. The fossils of the bone bed were eventually all collected, and the site was closed in 2008.

Two research projects organized by Dr. Benton that were extremely important for the science and the management of fossil resources in Badlands National Park were two multi-year fossil and geologic surveys within the Brule Formation in the North Unit of the park. The first, informally known as the Scenic Bone Bed Project, was a survey of the detailed paleontology and geology of the lower and middle Scenic Member in the western half of the North Unit. The project was active during the summers of 2000 to 2002, with the final report compiled by Dr. Benton in 2007. The second project, the Poleslide Bone Bed Project, was a survey of the paleontology and geology of the lower Poleslide Member in the eastern third of the North Unit. The Poleslide Project research was active in the summers of 2003 to 2005, and the final report was compiled in 2009 (Benton et al., 2009). The research for both projects included the location and description of fossils sites by two paleontology crews, one overseen by Dr. Benton and the other by Carrie L. Herbel, then the collections manager at the South Dakota School of Mines Museum. The paleosols associated with many of the individual bone beds were described by Dr. Dennis Terry and his students, contributing to our understanding of the origins of the bone beds. Dr. Emmett Evanoff of the University of Northern Colorado worked out the detailed stratigraphy (distribution and sequence) of rock layers in the Scenic and Poleslide members of the North Unit of Badlands National Park. This work allows the widespread and scattered bone beds to be placed in the proper order in time and space. Much of the following discussion of the geology, taphonomy, paleoenvironments, and paleontological resource management of this book is derived from these studies and subsequent work in the Badlands National Park.