Pittsburgh’s Lawrenceville neighborhood is definitely where it’s at. “Gus’s Café gives you a chance to show your DJ prowess at Open Turntables every Monday,” writes Chloe Detrick in NEXTpittsburgh, a publication that bills itself as the source of information about cool stuff in Pittsburgh. “On Wednesday, head over to Brillobox to test your knowledge at Pub Quiz night. If you like improv, keep an eye on Unplanned Comedy’s calendar.”2 Lawrenceville has a dog park and a place where you can launch your kayak into the Allegheny River, right under the 40th Street Bridge. On Butler Street, the neighborhood’s main drag, hip new stores and restaurants are supplanting the delis and hardware stores.

On one block, channeling two of the principal passions of the Young Grads we met in chapter 2, a yoga studio and a bike store sit side by side. Across the street in the next block are Café Gepetto, Gerbe Glass (a glass artists’ studio), and Bierport, which bills itself as “Pittsburgh’s great beer destination,” with nineteen beers on tap and over 800 more bottled and canned beers to choose from. In addition to drinking beer, patrons of Bierport can participate in educational classes, brewmaster visits, and food pairings. Eight years earlier, Bierport was Starr Discount, “Lawrenceville’s largest convenience store,” Gerbe Glass a hair salon, and Café Gepetto a shot-and-beer joint.

In 2000, despite a few urban pioneers here and there, Lawrenceville was an aging white working-class neighborhood, where 36 percent of the residents were over sixty-five. The numbers tell the story. Looking at the heart of what is known as Lower Lawrenceville,3 from 2000 to 2014 median household incomes more than doubled, going from $19K to $49K—while citywide, they went from $29K to $40K. The share of college graduates in the area’s population went from 14 percent to 36 percent, and the millennial share from 11 percent to 23 percent. In other words, over little more than a decade Lawrenceville flipped. It became a neighborhood of younger and increasingly affluent people. In other words, one might say it was gentrified.

If there is one word that has come to stand for all of the conflicts, controversies, and the sheer existential angst associated with the twenty-first-century urban revival, it is gentrification. While its roots may be economic, gentrification is far more than an economic phenomenon. It raises sensitive social, political, and cultural issues, prompting complex questions about the power relationships that underlie urban change, and about to whom a city or neighborhood belongs—or whether that question should even be asked. To understand gentrification, and the role it plays in the changes currently going on in America’s industrial cities, we need to parse these different meanings and subtexts.

The word gentrification itself was coined in 1964 by British sociologist Ruth Glass, looking to put a name to her observation that “one by one, many of the working-class quarters of London have been invaded by the middle classes….”4 From the beginning, as Glass’s choice of words suggests, it was never meant to be an objective description of a neutral phenomenon, but a politically charged and indeed pejorative term. Georgetown law professor J. Peter Byrne writes that “the very word ‘gentrification’ implies distaste,”5 while journalist Justin Davidson put it even more strongly: “It’s an ugly word, a term of outrage.”6 For that reason, many people, myself included, have tried to avoid the term when talking about what may be going on in a given city or neighborhood. By now, though, it is too firmly grounded in how people talk about cities to be easily sidestepped.

At the same time, it is dangerously misleading when it is seen, as is often the case, as a phenomenon outside the context of the larger ebb and flow of neighborhood change, or as a frame for venting outrage over any of the many ways in which social injustice and inequity are perpetuated in American cities. There is nothing inevitable about gentrification. As long as there have been cities and those cities have had neighborhoods, they have been changing, some moving upward and some downward. In most of America’s legacy cities, though, more hard-working families are seeing their quality of life erode and their home equity disappear as their neighborhoods decline than there are people living in places where affluent people are moving in and where house prices are going up. Still other neighborhoods are hollowing out as all but the poorest residents flee, and whole blocks of homes and storefronts are abandoned. To understand what’s going on in our cities, we need to see gentrification as part of this larger picture.

At its core, gentrification is economic. In its most widely recognized form, it is the process by which a formerly lower-income neighborhood like Lawrenceville draws a growing number of more affluent residents, at some point reaching a critical mass that changes the character of the neighborhood in fundamental ways. Businessdictionary.com defines gentrification in a way that goes to the heart of the issue: “the process of wealthier residents moving to an area, and the changes that occur due to the influx of wealth.”7 While the term is sometimes used in other contexts, gentrification is most fundamentally about what happens in urban neighborhoods when they experience an influx of wealth in the form of higher-income households.

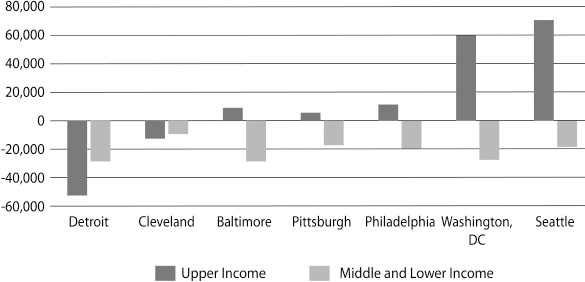

When it comes to growth in the number of wealthier households, American cities are a mixed bag. A handful of cities I like to call “magnet” cities, cities like Seattle and Washington, DC, are seeing an extraordinary influx of mostly young higher-income residents, profoundly changing those cities’ social and economic profile. Figure 5-1 compares those two cities with four legacy cities. It shows how the number of people in upper-income households, earning 25 percent more than the national median income, or roughly $70,000 per year or more in 2015, and the rest, the middle- and lower-income households, have changed between 2000 and 2015.

Figure 5-1 The uneven influx of wealth: change in number of households by income, 2000–2015. (Source: US Census Bureau)

Wealth is reshaping Seattle and Washington. Since 2000, upper-income households have been growing by 4,000 a year in Washington, DC, and almost 5,000 a year in Seattle. By comparison, while the fact that there is any net influx of even moderately wealthy people into Baltimore and Pittsburgh after decades of decline represents a dramatic shift from the past, the fact remains that this influx is still small, and far less than the continuing outflow of less affluent families. Finally, Detroit and Cleveland are seeing a net outflow of all family types, affluent and otherwise.

The graph is a quick and dirty way of getting a handle on the extent to which gentrification, in the sense described above, is likely to be taking place. Neighborhoods in Washington, DC, and Seattle are changing virtually overnight. Large parts of those cities have already been or are being gentrified, and thousands of new homes and apartments are being constructed. Even in areas like Anacostia, Washington’s poorest neighborhood, where little demographic change has taken place to date and where the residents are still largely poor and near-poor, the sheer pressure of growth has pushed house prices upward. As I write this in December 2016, a developer is offering a new house for $600,000 on a block of modest frame houses in a section of Anacostia where the average family earns barely $20,000 a year:

Existing structure will be razed and a FABULOUS NEW 4-SIDED BROWNSTONE HOME will be built. Delivery in February 2017. This home will boast AMAZING VIEWS of DC. It will feature 4 large bedrooms, 4.5 luxurious bathrooms, a chef’s kitchen, and fine finishes. 2,700 SF above grade. With an “optional elevator,” this home will be a dream come true.8

Washington, DC, and Seattle are outliers among American cities. The picture is very different in Baltimore and Pittsburgh. Both cities are seeing gentrification, but it is confined to small parts of both cities—mainly areas near downtown, major universities, and medical institutions—and is not spilling over much to other neighborhoods, the way one sees in Anacostia. In Baltimore, it’s only a short walk from thriving Bolton Hill to Sandtown-Winchester or Mondawmin. While a row house will sell for $500,000 or more in Bolton Hill, a seller in Mondawmin, where boarded-up, abandoned houses can be seen on almost every block, might be lucky to get $20,000 for what is basically the same house.

Will Sandtown-Winchester or Mondawmin ever gentrify? It is impossible to tell for sure, and ever is a long time, but despite the rhetoric of those who see every empty house as a stalking horse for gentrification, the likelihood is vanishingly small, at least in the foreseeable future. Wealth in Baltimore is growing, but it’s growing slowly, and there are lots of places available to even moderately affluent young people which don’t nearly require such a leap of faith. Elsewhere, the threat or the promise of gentrification, depending on one’s perspective, remains remote.

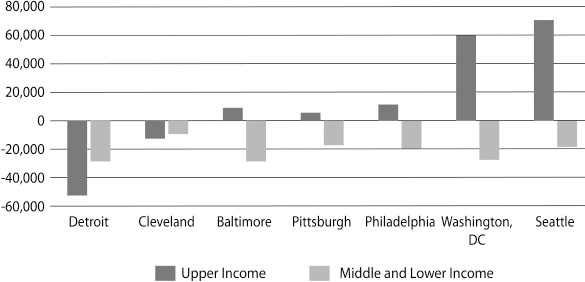

The same is true in Pittsburgh. To measure gentrification in Pittsburgh, I looked at change in two features for each census tract: an increase in median household income at least 25 percent greater than the citywide average increase, and an increase in median house value at least 25 percent greater than the citywide average increase, between 2000 and 2015. Then I included only those tracts that were low- or moderate-income areas in 2000. Only eight out of more than one hundred census tracts in Pittsburgh met all the criteria, shown in figure 5-2. They may not be the only areas in Pittsburgh where prices and incomes are rising, but they’re the only areas where it’s happening that were not already fairly well-to-do in 2000.

Figure 5-2 Gentrification in Pittsburgh, 2000–2015. (Source: PolicyMap)

If gentrification is a remote prospect for distressed areas in Baltimore or Pittsburgh, it is even more so in Cleveland or Detroit, where more wealth is still flowing out of those cities than is flowing in. While small pockets of revival exist in both cities, like Tremont in Cleveland or Corktown in Detroit, they are small and few in number. Decline is a far more pervasive reality, not only in areas that have long been distressed and disinvested, but even in areas that were healthy neighborhoods until recently, as I’ll describe in the next chapter. To the extent that wealth is flowing in, little of it is going into residential neighborhoods. Instead, almost all is going into areas like downtown Detroit or University Circle where few people lived before. In city after city, downtowns are becoming the new upscale neighborhoods.

What has been going on in downtowns like Detroit’s may actually be the biggest transformation story in America’s once-industrial cities. To understand why, we need to step back briefly into the history of American downtowns. The early-twentieth-century American downtown was a bustling, crowded, dynamic place, which downtown historian Robert Fogelson has described as “an extremely compact, highly centralized, largely depopulated business district to which nearly all the residents, even those who lived far away, would come every day to work, to shop, to do business, and to amuse themselves” (emphasis added).9

While in the small cities of the early years of the American republic downtowns and residential areas were not clearly distinguished, that changed dramatically during the late nineteenth century, as the growth of cities, and the business activity that came with that growth, gradually pushed residential uses out of downtowns. Most urban thinkers of the time saw this as a good thing; in 1871, Frederick Law Olmsted, the designer of Central Park, saw the “strong and steadily increasing tendency” toward the separation of businesses and residences as part of the “law of progress,” and “a fixed tendency among civilized men.”10 The early-twentieth-century downtown was crowded during the day but largely abandoned at night. Except for a handful of janitors and the denizens of the skid rows that popped up on the edges of some downtowns, people lived elsewhere. They lived in the residential areas that were being built all around downtown and used the burgeoning networks of subways, streetcars, and street and elevated railways to get conveniently in and out of downtown.

The 1920s may have been the high point of the traditional American big-city downtown. Highly ornamented skyscrapers with spires, turrets, and exuberantly decorated lobbies went up by the hundreds. Downtown department stores were at their grandest. John Wanamaker’s downtown Philadelphia store, which he had opened in 1874, was completely rebuilt in 1911, and reopened with 2 million square feet of space covering an entire city block, featuring a 150-foot-high Grand Court with the world’s second largest organ and a great eagle recovered from the 1903 St. Louis World’s Fair. With the Great Depression, though, downtowns, most heavily overbuilt from the 1920s’ building boom, collapsed. Construction ground to a halt, values plummeted, and vacancies skyrocketed. In most cities, the tallest building in 1929 was still the tallest three decades later.11

Although downtowns were struggling, they were still the centers of urban life into the 1960s. When I moved to the Trenton area in 1967, downtown Trenton was not what it was, by all accounts, but it was still the place to be. It had three movie theaters, five department stores—although one closed just about the same time I arrived—and the local custom of driving into downtown and driving around and around on Saturday nights, in a sort of wacky motorized parody of the Spanish paseo, was still alive. Within ten years, though, it was all gone. The bustling city seen in figure 5-3 was gone. The movie theaters were closed, the department stores had closed or moved to the new suburban malls, and no one drove downtown on Saturday night anymore.

Figure 5-3 Downtown Trenton in the 1940s. (Source: Alan Mallach collection)

The solution, if that’s the right word, that politicians, planners, developers, and downtown business people came up with was urban renewal. Large tracts of downtown business districts and nearby residential areas, usually low-income and often black, were cleared for new office towers, shopping malls, and highways. Expectations were high; as urban renewal chronicler Jon Teaford writes, “At the beginning of each project, planners presented drawings of a jet-age rebuilt city, with glistening high-rise towers in fountain-adorned plazas. Metropolitan newspapers faithfully reprinted these images, rallying support for proposals that seemed to promise a transformation from grit to glitter.”12 From one city to the next, large parts of the prewar fabric of downtown was obliterated in the name of progress, yet the results rarely lived up to expectations. Many projects never got built, while many of those that did turned out to be failures, either economically or aesthetically, or both. The highways seemed to do little or nothing to reverse downtown decline, as the remaining businesses continued to flee for the suburbs.

Luring upscale households to live in downtown was often part of the plan. Downtown housing, though, generally took the form of sterile, boxlike high-rise towers in a sea of parking, with few amenities beyond, perhaps, a deli and a dry cleaners establishment. A few, like Lafayette Park in Detroit, were big enough to create their own self-contained world, but most failed. As Teaford sums it up, “In one city after another, middle- and upper-income Americans shunned areas whose reputations had been so odious that they required renewal. With millions of new homes on the market during the 1950s and 1960s, there was no compelling reason to opt for life amid the bulldozed wastelands of once-blighted areas.”13

That remained the picture over the next few decades. More office buildings were built during the eighties and nineties, and here and there an imaginative project like James Rouse’s Inner Harbor project in Baltimore caught fire, but downtowns continued to be shunned by most people except as a place to work, while, even as new office buildings were constructed, the once-shining skyscrapers of the 1910s and 1920s increasingly stood empty, millions of square feet abandoned by tenants and, increasingly, by their owners. “By the early 1980s,” architectural historian Michael Schwarzer writes, “downtown appeared a lost cause. It was burdened by aging, emptying office buildings, struggling discount retailers, and vanishing entertainment complexes.”14

Exactly when and how things started to change is hard to tell, and a lot of it has to do with the Young Grads we met in chapter 2 moving to the cities first in the 1990s, and then in even larger numbers after the turn of the millennium. The story of St. Louis’s Washington Avenue illustrates their role, but also highlights the importance of many other players. I mentioned Washington Avenue briefly in chapter 2, the onetime garment and shoemaking district shown in its heyday in figure 5-4. By the early 1980s, all the factories had moved out, leaving block after block of magnificent early-twentieth-century five- and six-story factory buildings behind.

Figure 5-4 St. Louis’s Washington Avenue in the early 1900s. (Source: Missouri History Museum, St. Louis)

Washington Avenue never emptied out completely. Even as the last factories were still winding down, one or two property owners had started to make just enough improvements to a couple of the buildings to make it legal for them to rent out cheap live/work space to artists. By the early 1990s, the avenue was mostly empty, but with just enough artists, galleries, and funky shops scattered here and there to make it a hub of St. Louis’s small counterculture scene. By that point, a few people were starting to pick up buildings on the avenue for pennies. One of them was a sculptor named Bob Cassilly, who bought a 250,000-square-foot building for sixty-nine cents per square foot and opened it in 1997 as the City Museum, an eclectic hodgepodge of everything and anything, which Mental Floss blogger Erin McCarthy calls the “coolest—and most entertaining—place on earth.”15 Meanwhile, in 1996, using federal housing subsidies, another developer had converted the Frances Building at the corner of 16th Street to Arts Lofts, live/work spaces for sixty low-income artists.

Developers started to realize that there were quite a few people interested in moving into old loft buildings along Washington Avenue. Their problem was that the rents they could charge weren’t high enough to cover the cost of restoring these magnificent old buildings—perhaps cheap to buy but expensive to restore. In 1997, though, the state of Missouri enacted what is called a Historic Tax Credit, a program that gave developers a major tax break for restoring and renting out historic buildings. Combined with the existing federal historic-preservation tax credit, the program meant that, with any luck, a developer could recover one-third or more of her cost from these tax breaks, meaning in turn, that she could charge the lower rents that the market demanded, and still make a decent profit.

That opened the floodgates. Before the end of 1999, eight separate redevelopment projects had been announced along Washington Avenue. By the end of 2000, nearly 500 apartments were under construction, and another 800 planned. By the end of 2004, 1,400 apartments had been completed since 1999, and another 1,000 were on the way.16 As buildings were restored, stores and restaurants opened their doors, with eighteen bars and restaurants along the avenue between 10th and 14th Streets alone. By 2007, although a building here or there still awaited renovation, the transformation of Washington Avenue was effectively complete. It took only twelve years, almost overnight in the real estate world.

What happened along Washington Avenue has its counterparts in the downtowns of every major older industrial city, and a fair number of small ones as well. In struggling Youngstown, Ohio, local developer Dominic Marchionda has turned five downtown office buildings into apartments, renting to a mix of Youngstown State University students, Young Grads, and a few retirees. What is behind this is that the physical shape and layout of traditional American big-city downtowns turns out to be the Young Grads’ dream environment. The density, the activity level, the combination of stores and restaurants on the ground floors and apartments or lofts overhead, the ability to get around on foot or by public transportation, all make it easier to create the “scene” I described in chapter 3, ultimately becoming a self-sustaining chain reaction.

The areas, though, which are drawing people back are not the areas that were “improved” through urban renewal in the fifties and sixties. In fact, the opposite. Washington Avenue was one of the few parts of downtown St. Louis to escape the urban renewal wrecking ball, something that is equally true of reviving downtown areas in Cleveland, Philadelphia, and elsewhere. The theory behind urban renewal, that cities had to rebuild themselves around the automobile in order to thrive, turned out to be no more sound than the medieval idea that the sun revolved around the earth. It was actually the opposite. Cities needed to maintain their urban character—their density, their diversity of buildings and people, and their mixture of uses and activities—to thrive. It was an expensive, painful lesson to learn.

Washington Avenue is not the only reason that the number of Young Grads in the city of St. Louis has been going up by 1,500–2,000 each year since 2010—up from 500 each year between 2000 and 2005—but it’s an important part of the picture. Since 2000, the population of the three census tracts that make up downtown St. Louis has more than tripled, going from 3,400 to 12,600. During the same period, the downtown population of Cleveland more than doubled, from 5,000 to 11,300.17

Every city has its own story that parallels the Washington Avenue story. In Detroit, downtown revitalization has been given a jump-start by billionaire Quicken Loans founder Dan Gilbert, to the point where some critics are calling downtown Detroit “Gilbertville.” A tally by the Detroit News in the spring of 2016 found that Gilbert-connected entities had spent $451 million to buy downtown properties, with at least eleven more deals still in the pipeline, and untold hundreds of millions more to restore the properties, converting them from office space to apartments—all in all probably over $2 billion.18 Along with the apartments, Gilbert’s buildings are drawing retailers popular with Young Grads, such as Nike, Under Armour, Moosejaw, and Warby Parker.

Whether Gilbert and his investors will get their money back, and if so, by when, are open questions. What is not in question is that his buildings are filling up, as Detroit has started to catch up with other cities like St. Louis and Pittsburgh in drawing Young Grads. On a balmy fall night in 2016, I found myself walking down Woodward Avenue, downtown Detroit’s main street. It was nearly 10:30 on a weeknight, but restaurants were open, young people were sitting at outdoor tables, knots of young people were gathered talking on the wide, brand-new sidewalks, and from time to time a jogger would come running by. For those like me who remember the emptiness of downtown Detroit only five or six years earlier, this was a sea change.

Is this gentrification, or something else entirely? Clearly, downtowns are not the “working-class quarters” Ruth Glass was writing about, and if displacement, direct or indirect, is one’s touchstone for gentrification, it is hard to make the case that that is going on to any extent in the course of what might be called the “residentialization” of downtown. At the same time, it is a form of transformation, not only physical but social and economic, as fundamental and as far-reaching as any neighborhood change characterized as “gentrification.”

In fact, the implications of downtown revitalization may be even more profound. Downtowns, at least in part because they were not residential areas, were historically a common ground within the city, nobody’s turf and open to all. In many cities, historically fragmented into a jigsaw puzzle of ethnic and racial enclaves, downtowns may well have been the only common ground those cities could offer. The significance of that common ground has frayed over decades of decline, but was never completely lost. As downtowns, though, become increasingly residential and redefine themselves as upscale neighborhoods, that could easily disappear, further cementing the spatial polarization that is increasingly the new reality of urban America. If only for that reason, the transformation of downtowns needs to be discussed in the same breath as gentrification, as another manifestation of how revival and inequality go hand in hand.

Another question has to do with spin-offs. While downtown residentialization may not displace anyone, the course of downtown revival can trigger powerful spin-offs, and a disproportionate number of gentrifying neighborhoods are in fact adjacent to reviving downtowns. This reflects what we know about which neighborhoods are more likely or less likely to gentrify.

Reviving neighborhoods tend to have a number of features that distinguish them from other areas, of which the first, and most important, is location. Revival does not jump around, leapfrogging from one area to another. It moves incrementally from areas that are already strong or from major nodes of activity, such as a downtown or a university campus. Exceptions to this rule are few and far between.

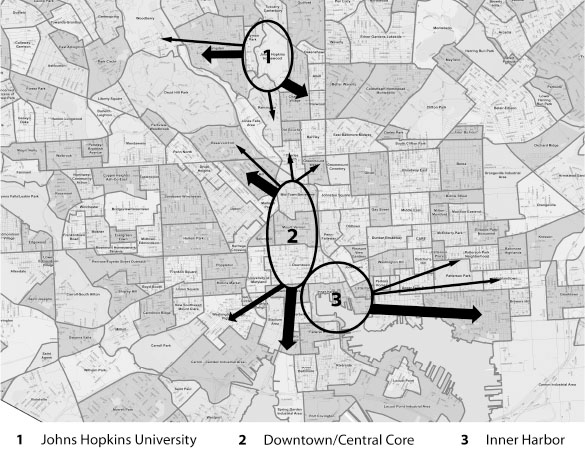

In Baltimore, gentrification has moved gradually east and south of the inner harbor from Fells Point to Canton and Patterson Park, and north of downtown toward the Johns Hopkins campus, as well as in a growing band of neighborhoods around the campus itself. Figure 5-5 shows what one might call Baltimore’s gentrification vectors; thick arrows show established middle- and upper-income areas—some of which are the product of earlier waves of gentrification in the 1970s or 1980s—and narrow arrows show areas that appear to be experiencing revival today. All of the vectors flow from one or another of three nodes—Johns Hopkins, downtown, and the Inner Harbor.

Figure 5-5 Baltimore’s gentrification vectors. (Source: base map from City of Baltimore Department of Planning, overlay by author)

The second feature is what designers call the neighborhood’s “fabric”—the weave of houses, small apartment buildings, and storefronts that collectively create the built landscape of the traditional urban neighborhood. In areas that gentrify, that fabric is still largely intact. Vacant lots, where houses have been demolished, are few in number. The houses themselves may not be architectural gems, but are generally attractive, if perhaps run-down, and reasonably close together. Such areas often have a shopping street running through them, built for walking rather than driving, as most places had before the automobile era. They almost always predate World War II, having been laid out before we started to design neighborhoods for cars rather than people.

Gentrifying areas are rarely the most distressed areas of a city, particularly those where the cumulative effect of demolishing vacant buildings has undone the neighborhood’s fabric, as can be seen in the street scene from North City St. Louis in the last chapter. Indeed, the idea one hears that urban demolition is a stalking horse for future gentrification is yet another urban myth; in reality, it more often creates a moonscape of vacant land that all but guarantees gentrification will not take place.

The third feature may come as a surprise to people who learn about gentrification from blogs and social media, but predominantly African American neighborhoods are less, not more, likely to experience gentrification than largely white, working-class neighborhoods. In a 2014 study of Chicago, sociologists Jackelyn Hwang and Robert Sampson found that “upward neighborhood trajectories tend to follow a pattern of Black and Hispanic neighborhood avoidance.”19 They found that neighborhoods that were more than 40 percent black or Hispanic were significantly less likely to gentrify than other similarly situated areas.

This pattern is not unique to Chicago; Todd Swanstrom and his colleagues in St. Louis found that only five out of thirty-five of what they called rebounding neighborhoods had more than 40 percent black population in 1970.20 In Baltimore, a city that is nearly two-thirds African American, hardly any of the gentrification vectors point to majority African American areas; in fact, they are largely concentrated in what Baltimore scholar-activist Lawrence Brown has called the city’s “White L,” the L-shaped area clearly visible in figure 5-5 that tends to be predominately white, in contrast to the “Black butterfly” that makes up most of the rest of the city.21 The same is largely true in Pittsburgh. Only two of the eight gentrifying census tracts shown earlier had 30 percent or more black population in 2000. One of those two is at most a borderline case of gentrification; although rising economically, it was still a poor area, and well below city averages in both income and house value in 2015.

Racial considerations are never far away in America’s urban centers, many of which became majority-black communities during the second half of the twentieth century. Since gentrification by its nature starts out as an uncertain proposition—the first urban pioneers have no idea who, if anyone, will follow them—race can be seen to add another layer of uncertainty, particularly for the mostly white families and individuals likely to be putting their resources on the line.

What happens when a neighborhood starts to change is a function of how the market works, which is based on the all but inexorable laws of supply and demand. If more people want to live in a particular area, demand for the homes in that area goes up. If the supply of housing does not go up at the same time, more people are now competing for the same pool of homes and apartments. If the people who now want to live there have more money to spend on housing than those who have previously done so, they will bid up the prices—whether sales or rental—of the housing. As prices rise, some people who already live in the neighborhood may be unable to stay, and more often, people like them will be less able to move in.

That is a very bloodless, abstract description. It depicts the underlying economic reality behind gentrification, but does not reflect the messiness on the ground. The process may be gradual and quiet, with a minimum of overt pressure or visible strain; or it may be faster and be accompanied by overt or covert conflict, ranging from the tensions of contrasting lifestyles and values to speculation, flipping, and intimidation. In cities like Pittsburgh or St. Louis, it is likely to be slower, in Washington or San Francisco, faster and with more visible conflict.

The initial stages of gentrification are usually fairly gradual, involving people making individual choices to buy or rent in a traditionally lower-income neighborhood; as Kalima Rose of PolicyLink writes, “At first, this causes little displacement or resentment. This process may occur over several years, and initially may cause little change in the appearance of long-disinvested communities.”22 While public investment in housing rehab, beautification, or transit may sometimes fuel gentrification, few if any cities have a grand design or plan for gentrification, even though it may sometimes seem otherwise to people living in gentrifying neighborhoods in hot markets like Brooklyn or Washington, DC. It is more likely to be informal and spontaneous, taking local planners and elected officials by surprise. More often, once a neighborhood begins to show significant signs of gentrification, the city may start to think after the fact about how it can move the process along, gracing the area with park improvements or new street lighting, or selling city-owned land to developers.

Whatever the intentions of the families wanting to move into a neighborhood, the low-key, informal quality of the first stages of gentrification eventually ends. Either the effort fizzles, the pioneers fade away, and the neighborhood reverts to its earlier state, or the potential profits to be made from the demand for the houses in the area bring out the members of what a 2014 public radio report called the “gentrification-industrial complex,” the “web of real estate leasing agents, listing agents, landlords, and investors whose business models are built on stoking and profiting from neighborhood change.”23 Individual actors, though, tend to be small operators marketing or flipping houses, or developers and contractors buying and restoring individual properties.

Large-scale developers usually come last, after the small fish have created an environment where lenders are now willing to put up the millions that developers need to get a major project off the ground. This may not be true in some “hot” cities like New York or San Francisco, where no neighborhood is immune from the intense market pressures at work in those cities, but it is generally true elsewhere. The first large-scale development to go up in Pittsburgh’s Lawrenceville neighborhood, a mixed-use project with 243 apartments, retail space, and a pedestrian walkway leading to a new one-acre park, was only announced in 2016, well after the newly upscale character of the area had already been firmly established.

Local developer Bart Blatstein’s role in the transformation of Philadelphia’s Northern Liberties area is a big, and unusual, exception. Northern Liberties, just north of Center City along the Delaware River, had been the “next hot neighborhood” in Philadelphia for decades. In fact, when my wife and I were house-hunting in the late 1970s, some of our hipster friends told us to look in that area. One Saturday morning, we drove around what was a wasteland of scattered clumps of row houses, vacant lots, and derelict industrial buildings, and quickly decided that it wasn’t for us, even if it was within walking distance (albeit a scary walk in those days) to the restaurants of Old City. Perhaps it was up and coming, but it had a long way to go. We weren’t that hip.

By the 1990s little had changed, except for a few contrarian artists here and there and a brief flurry of activity that was snuffed out by the real estate recession of the late 1980s. Blatstein, who had made a fortune building conventional shopping centers, saw the area’s potential, and started buying properties there in the 1990s, culminating in his acquiring the landmark Schmidt’s Brewery complex in 2000. With enough capital of his own so that he didn’t need to rely on bankers, he began developing properties in the area.

Originally, Blatstein had planned to build another shopping center on the site and get out, but “then,” he said, “the midlife crisis hit, and I thought, What do I do? Do I get the bright red Ferrari? And then I decided, Let me do the creative thing here. I have the opportunity to do something really cool here.”24 What he created was the Piazza at Schmidt’s, since renamed Schmidt’s Common, which opened in 2009. Inspired, Blatstein said, by Rome’s Piazza Navona, the complex contains office space, stores, and over 400 apartments surrounding a nearly two-acre plaza or piazza, which has since become a popular gathering place for Philadelphia’s Young Grads.

It’s impossible to tell how often pressure of one sort or another is part of the gentrification process, but there’s no doubt that it happens. As New York legal aid lawyer Scott Stamper says, “We’ve seen a real rise in landlords stalking, threatening, and badgering tenants with unwanted buyout demands. This isn’t negotiation, it’s harassment.”25 Homeowners receive letters from realtors, describing how much a nearby house sold for, and get notes slipped under their front doors, such as the one that appeared in Brooklyn, as described by Jerome Krase and Judith DeSena: “I am interested in buying your building. I will pay Cash now or in the future. Please give me a call if you are ready to sell.”26 Homeowners may receive calls from people trying to buy them out, or find would-be buyers on their doorsteps making their pitch in person. Harassment may never be too far away, while low-income, elderly homeowners with few other assets and painful debt burdens may easily be convinced to sell for less than the true value of their homes. At the same time, gentrification offers a rare opportunity for struggling lower-income homeowners who see the value of their sole asset rising to the point that it really means something, if they can realize that value.

Gentrification of a neighborhood brings benefits, but uneven ones. Once a neighborhood begins to change, it is easy to look back with rose-colored glasses and recreate an idealized image of the past. The bodega down the street that has been replaced by a coffee place had overpriced milk, and tired, often rotten produce. The young people clustering on the street corner were not always engaged in harmless pursuits. People remember the cookouts, but not the fear. Moreover, as City Observatory’s Joe Cortright aptly points out, the idea that “if a neighborhood doesn’t gentrify, it somehow stays the same” is a fallacy.27 The reality is that today most neighborhoods that don’t revive, go downhill.

As neighborhoods revive, they become safer, cleaner places. Vacant houses, which undermine the health and safety of residents as well as the value of their property, are rehabilitated and reused. New stores and businesses open; some may replace existing ones, but many others fill long-vacant storefronts. The yoga studio may have little appeal to longtime residents, but they are more likely to appreciate the new grocery store with its fresh produce. Neighborhoods that have seen all the problems of blight and concentrated poverty, with all of the devastating effects those conditions have on both child and adult life outcomes, have become less blighted and more integrated.

Public services may improve, not just because the area is becoming more affluent but because the newcomers are often more effective advocates for their neighborhoods. In one changing neighborhood in St. Louis, newcomers took the lead in starting City Garden, a Montessori charter school committed to maintaining an economically and racially integrated student body, which has since been recognized as one of the outstanding schools in the region. Over and above the direct benefits to neighborhoods, financially and economically stressed cities benefit from a more economically diverse population and higher tax revenues, which in turn enhance their ability to maintain their physical environment and provide better public services. These are not insignificant benefits, and there is evidence that in legacy cities they are shared by many gentrifying neighborhoods’ longtime residents.

The issue is not only whether those benefits are shared to any meaningful extent by lower-income families, but whether they outweigh other damage done in the process. The critique of gentrification typically identifies three distinct forms of harm: displacement, loss of housing affordability, and what might be called cultural displacement. All three demand attention, but to see all change as inherently harmful is to fail to recognize the complexity of what is actually going on and what might or should be done about it. This is particularly the case in cities like Philadelphia or St. Louis where, in contrast to Washington, DC, or San Francisco, neighborhood transitions tend to be more gradual, with less of the feeding frenzy that takes place in magnet cities, and where rents and house prices even in gentrifying neighborhoods are rarely stratospheric. Indeed, it is striking how much of what a national audience reads about the evils of gentrification emanates from New York and San Francisco among the handful of magnet cities, and how little from the far larger number of legacy cities.

At one level, common sense would suggest that displacement is an inevitable product of gentrification. If prices go up to the point that they are no longer affordable to many of the area’s residents, they will be displaced. It’s actually far from that simple. It’s important to distinguish between displacement in the literal sense—when a tenant is forced to move by gentrification, either as a result of a rent increase that renders her unable to afford her apartment, or some other form of pressure from her landlord—and longer-term loss of affordability. Despite individual horror stories, most of which seem to come from New York City, the former is rarer and much harder to establish than one might think.

Turnover of urban renters, particularly low-income renters, for all kinds of reasons, is extremely high. The median stay of urban renters in the same house or apartment is barely two years. Much of this turnover is involuntary, but for reasons unrelated to gentrification. As Matthew Desmond has powerfully shown in his book Evicted, poor tenants, particularly single mothers with small children, face a constant struggle to come up with the rent every month for even the most modest house or apartment. Their lives are a desperate battle to survive on the edge of eviction, doubling up, and potential homelessness, a battle they often lose. This reality has nothing to do with gentrification. It is about what it means to be poor in America, and about the disgraceful way in which we as a nation fail to recognize, let alone address, the housing needs of the poor.

The issues are different for homeowners. The conventional wisdom is that lower-income homeowners are forced out of gentrifying neighborhoods as a result of skyrocketing property taxes, themselves the result of the dramatic rise in property values. Again, I would not suggest that this never happens; what little research has been done on the question, however, suggests that it is not that widespread. Some cities have tried to prevent it, although at a cost. Through its Longtime Owner Occupant Program, or LOOP, Philadelphia has provided tax relief for homeowners who have lived in their homes for ten years or more and are facing rapidly rising property tax bills; 17,000 people qualified for the program in the first two years.28 This looks like a pretty blunt instrument, though. Given the generous income ceilings for the program—from $83K for a single individual to nearly $119K for a family of four—many of these families are at little risk of losing their homes. Instead, the financially strapped city is going without property taxes from a large number of people in order to benefit a much smaller number.

The real issue is well summed up by journalist Jarrett Murphy, who writes, “The issue isn’t displacement of the poor, but replacement.”29 In a poor neighborhood, when a lower-income tenant leaves her current home—by choice, eviction, or otherwise—she is usually replaced by another low-income tenant, someone much like her. In a neighborhood that is seeing growing demand from higher-income people, she is more likely to be replaced by a higher-income tenant, or perhaps—if the home is a single-family house, rather than an apartment—by a home-buyer. Looking at a neighborhood as a whole, this process is likely to take place gradually, over the course of many moves by many tenants over many years. The question is, though, under what conditions should this be seen as a problem associated with gentrification?

While replacement may be all but total in a neighborhood in the path of gentrification in Brooklyn, the picture is quite different in a city like St. Louis. In the St. Louis neighborhoods that Swanstrom and his colleagues studied, they found that “the influx of higher-income white professionals has not caused rents to soar to the point that poor populations are displaced entirely. […] Rebound neighborhoods remain the most economically diverse neighborhoods in the region.” Consistent with those findings, I found that while house sales prices had risen faster in a cluster of gentrifying neighborhoods than they did citywide in St. Louis from 2000 to 2015, rents actually went down, although very slightly, relative to the city as a whole. Even then, house prices were still far from out of reach of most people, with houses selling in most of these neighborhoods for prices from around $150K to not much more than $200K. Swanstrom also points out that over the forty-year period he studied, from 1970 to 2010, “Only 5,816 people live in census tracts that transitioned … from high poverty to low poverty, whereas 98,953 live in neighborhoods that became newly poor during that period.”30

Figuring how much harm replacement does hinges on two separate issues: first, whether nearby areas provide housing that is as affordable as where the tenant previously lived, and second, the way in which it changes the neighborhood and how those changes affect people. On the first issue, we must once again distinguish between magnet cities and legacy cities. In a city like Washington, DC, prices and rents are going up all over the city, and finding affordable housing anywhere in the city can be increasingly difficult. Families double up, put up with overcrowding, or move out of the city entirely to Prince Georges County or even farther afield. In Baltimore or St. Louis, they may have to do little more than move a few blocks to find housing no more expensive than their last home.

If the family involved is poor or near-poor, that does not mean that they will find high-quality housing at a truly affordable price, unless they are among the chosen few who win the affordable-housing lottery and get a housing voucher or an apartment in a high-quality affordable-housing project. But, again, that is not the result of gentrification; it is the result of poverty and systemic housing costs that all but guarantee that even crumbling, roach-infested housing is too expensive for a poor family to afford without hardship. It is also the result of our nation’s failure to come up with a housing policy or provide the resources that might make the pledge Congress made back in 1949 of “a decent home in a suitable living environment for every American family” more than empty rhetoric.

The replacement triggered by gentrification does not only change people’s lives, it also changes the neighborhood and creates a neighborhood populated by an increasingly heterogenous group of people, black and white, young and old, well-to-do and struggling, with different values, tastes, and norms. Even more, it means that a neighborhood that people thought of as their more or less clearly defined territory is no longer theirs. This can mean many things. It can be as fundamental as identity, as Michelle Lewis, a black former resident of one Portland neighborhood told a reporter: “It’s a horrible feeling, to come to a neighborhood where you grow up in, and have the people there look at you as if you don’t belong.” The reporter added that Lewis “recalled … the funeral home where she buried her grandfather. Little Chapel of the Chimes is now a craft beer pub.”31

In a 2014 gentrification rant that went viral, film director Spike Lee put it differently: “You just can’t come in the neighborhood. I’m for democracy and letting everybody live but you gotta have some respect. You can’t just come in when people have a culture that’s been laid down for generations and you come in and now shit gotta change because you’re here?”32 Newcomers bring different norms and preferences with them. Conflicts can arise over almost anything—noise, trash, or as one longtime resident of a changing St. Louis plaintively said, “Why can’t we do what we do? Why can’t we put chairs outside of our houses?”33 It can be about less tangible matters like attitudes, as in the words of Bill Francisco, a longtime resident of Philadelphia’s gentrifying Fishtown neighborhood: “There are too many real problems in life in general to be weird about a bar or a restaurant. It’s about respect, that’s all.”34

It is impossible not to sympathize with the sense of loss that’s reflected in these comments. At the same time, change is a constant in American neighborhoods, and while respecting the passion and pain in Spike Lee’s voice, the reality is that shit does change one way or another all the time, and that the pain and loss are just as real and maybe worse for people living through decline as a neighborhood they remember as warm and supportive deteriorates, houses are abandoned on once-stable blocks, crime increases, and families no longer allow their children to play outside. Decline gets far less ink than gentrification, for reasons which I will explore in the next chapter.

Why people react to gentrification the way they do, though, is driven by a separate but closely related issue that in turn is part and parcel of the racial dimension that plays such a large role in this conversation. My friend Paul Brophy, one of the wisest thinkers about these issues I know, taught a graduate seminar at Washington University in St. Louis a few years ago and told me a story that captures this better than anything else I can think of. A young African American student in the class was clearly unhappy with much of his presentation; finally, he made his point directly. “Listen, professor,” he said. “When you talk about gentrification, you talk about numbers, about incomes and house prices and such. When we talk about gentrification, it’s about powerlessness.”

The question of power is never far from any discussion of urban change, whatever one’s ideological stripes. If you are poor, it is hard not to believe that the system is rigged against you. If you are poor and black, infinitely more so. It is hardly surprising that perhaps the greatest disparity between the rhetoric of gentrification and the reality of it on the ground is in Detroit. Over 80 percent of the city’s population is African American, and yet almost every decision that has any significant bearing on Detroit’s future is made by a small group of white men. Detroit is also a place where the deeply offensive proposition that it is a blank slate waiting to be brought back to life by newcomers has become a recurrent media theme.

In that context, gentrification becomes a powerful code word, as reporter Jake Flanagin writes: “The most unsettling thing about gentrification, however, is how it reflects the utter and complete lack of control the poor and the nonwhite have in where they are permitted to live. And this potential Great Return to Detroit is a high-contrast, technicolor example.”35 In a similar vein, a woman protesting against the city’s policy of shutting off water service for nonpayment asserted that “the Detroit water shut-offs are gentrification on steroids.”36 To that protestor, the meaning of gentrification has long since transcended any connection to neighborhood change; to her, it is any policy that further impoverishes and marginalizes the already poor and marginalized members of society. The reality that far more middle-class families and individuals are moving out of Detroit than are moving in is, from this perspective, irrelevant.

In the final analysis, gentrification is about neighborhoods, but it is also about much more than neighborhoods. At its most fundamental level, it is about the changes that take place in lower-income neighborhoods when more-affluent people begin to move in, house prices go up, and coffee places and craft beer pubs open up. That is a complicated enough matter, which can be both good and bad for people, but often not for the same people. At a second level, though, neighborhood change reflects a larger change in the cities themselves, part and parcel of the larger economic transformation that saw those cities go from an economy based on people’s strength and willingness to do hard physical labor, to one based on specialized skills and higher education, a change that is increasingly sidelining thousands of these cities’ residents and erstwhile workers. While the changing urban scene is indeed bringing gentrification to many neighborhoods, it is bringing accelerated decline to still more. Finally, though, it is about power, and how economic polarization breeds political polarization, and how both become increasingly racialized, shifting the ways in which the reins of power are distributed in the city. It is the cri de coeur of the thousands of people who rightfully feel marginalized by their city’s transformation.

That said, it is still also about neighborhoods. And when we look at the neighborhoods in America’s legacy cities, as I said at the beginning of this chapter, the story of neighborhood decline is a far bigger one, certainly in terms of the sheer number of people, homes, and city blocks affected, than gentrification. In the next chapter, I will first look at the numbers and show how decline and gentrification compare in a few cities, and then delve into why, even as one might say that many of these cities are prospering beyond even their boosters’ wildest dreams, neighborhood decline is not only still present, but a growing crisis.