THE history of Greek astronomy in its beginnings is part of the history of Greek philosophy, for it was the first philosophers, Ionian, Eleatic, Pythagorean, who were the first astronomers. Now only very few of the works of the great original thinkers of Greece have survived. We possess the whole of Plato and, say, half of Aristotle, namely, those of his writings which were intended for the use of his school, but not those which, mainly composed in the form of dialogues, were in a more popular style. But the whole of the pre-Socratic philosophy is one single expanse of ruins;1 so is the Socratic philosophy itself, except for what we can learn of it from Plato and Xenophon.

But accounts of the life and doctrine of philosophers begin to appear quite early in ancient Greek literature (cf. Xenophon, who was born between 430 and 425 B.C.); and very valuable are the allusions in Plato and Aristotle to the doctrines of earlier philosophers; those in Plato are not very numerous, but he had the power of entering into the thoughts of other men and, in stating the views of early philosophers, he does not, as a rule, read into their words meanings which they do not convey. Aristotle, on the other hand, while making historical surveys of the doctrines of his predecessors a regular preliminary to the statement of his own, discusses them too much from the point of view of his own system; often even misrepresenting them for the purpose of making a controversial point or finding support for some particular thesis.

From Aristotle’s time a whole literature on the subject of the older philosophy sprang up, partly critical, partly historical. This again has perished except for a large number of fragments. Most important for our purpose are the notices in the Doxographi Graeci, collected and edited by Diels.2 The main source from which these retailers of the opinions of philosophers drew, directly or indirectly, was the great work of Theophrastus, the successor of Aristotle, entitled Physical Opinions ![]() . It would appear that it was Theophrastus’s plan to trace the progress of physics from Thales to Plato in separate chapters dealing severally with the leading topics. First the leading views were set forth on broad lines, in groups, according to the affinity of the doctrine, after which the differences between individual philosophers within the same group were carefully noted. In the First Book, however, dealing with the Principles, Theophrastus adopted the order of the various schools, Ionians, Eleatics, Atomists, &c., down to Plato, although he did not hesitate to connect Diogenes of Apollonia and Archelaus with the earlier physicists, out of their chronological order; chronological order was indeed, throughout, less regarded than the connexion and due arrangement of subjects. This work of Theophrastus was naturally the chief hunting-ground for those who collected the ‘opinions’ of philosophers. There was, however, another main stream of tradition besides the doxographic; this was in the different form of biographies of the philosophers. The first to write a book of ‘successions’

. It would appear that it was Theophrastus’s plan to trace the progress of physics from Thales to Plato in separate chapters dealing severally with the leading topics. First the leading views were set forth on broad lines, in groups, according to the affinity of the doctrine, after which the differences between individual philosophers within the same group were carefully noted. In the First Book, however, dealing with the Principles, Theophrastus adopted the order of the various schools, Ionians, Eleatics, Atomists, &c., down to Plato, although he did not hesitate to connect Diogenes of Apollonia and Archelaus with the earlier physicists, out of their chronological order; chronological order was indeed, throughout, less regarded than the connexion and due arrangement of subjects. This work of Theophrastus was naturally the chief hunting-ground for those who collected the ‘opinions’ of philosophers. There was, however, another main stream of tradition besides the doxographic; this was in the different form of biographies of the philosophers. The first to write a book of ‘successions’ ![]() of the philosophers was Sotion (towards the end of the third century B.C.); others who wrote ‘successions’ were a certain Antisthenes (probably Antisthenes of Rhodes, second century B.C.), Sosicrates, and Alexander Polyhistor. These works gave little in the way ol doxography, but were made readable by the incorporation of anecdotes and apophthegms, mostly unauthentic. The work of Sotion and the ‘Lives of Famous Men’ by Satyrus (about 160 B.C.) were epitomized by Heraclides Lembus. Another writer of biographies was the Peripatetic Hermippus of Smyrna, known as the Callimachean, who wrote about Pythagoras in at least two Books, and is quoted by Josephus as a careful student of all history.3 Our chief storehouse of biographical details derived from these and all other available sources is the great compilation which goes by the name of Diogenes Laertius (more properly Laertius Diogenes). It is a compilation made in the most haphazard way, without the exercise of any historical sense or critical faculty. But its value for us is enormous because the compiler had access to the whole collection of biographies which accumulated from Sotion’s time to the first third of the third century A. D. (when Diogenes wrote), and consequently we have in him the whole residuum of this literature which reached such dimensions in the period.

of the philosophers was Sotion (towards the end of the third century B.C.); others who wrote ‘successions’ were a certain Antisthenes (probably Antisthenes of Rhodes, second century B.C.), Sosicrates, and Alexander Polyhistor. These works gave little in the way ol doxography, but were made readable by the incorporation of anecdotes and apophthegms, mostly unauthentic. The work of Sotion and the ‘Lives of Famous Men’ by Satyrus (about 160 B.C.) were epitomized by Heraclides Lembus. Another writer of biographies was the Peripatetic Hermippus of Smyrna, known as the Callimachean, who wrote about Pythagoras in at least two Books, and is quoted by Josephus as a careful student of all history.3 Our chief storehouse of biographical details derived from these and all other available sources is the great compilation which goes by the name of Diogenes Laertius (more properly Laertius Diogenes). It is a compilation made in the most haphazard way, without the exercise of any historical sense or critical faculty. But its value for us is enormous because the compiler had access to the whole collection of biographies which accumulated from Sotion’s time to the first third of the third century A. D. (when Diogenes wrote), and consequently we have in him the whole residuum of this literature which reached such dimensions in the period.

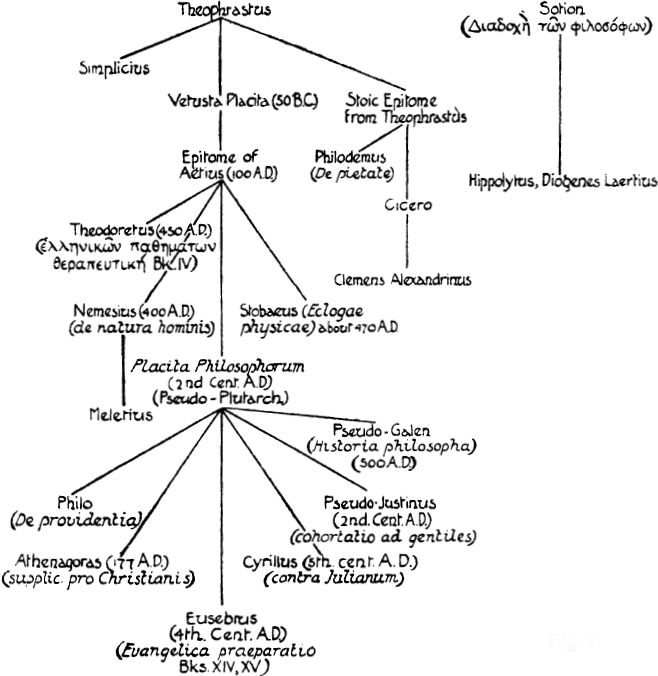

In order to show at a glance the conclusions of Diels as to the relation of the various representatives of the doxographic and biographic traditions to one another and to the original sources I append a genealogical table4:

Fig. 1

Only a few remarks need be added, ‘Vetusta Placita’ is the name given by Diels to a collection which has disappeared, but may be inferred to have existed. It adhered very closely to Theophrastus, though it was not quite free from admixture of other elements. It was probably divided into the following main sections: I. De principiis; IL De mundo; III. De sublimibus; IV. De terrestribus; V. De anima; VI. De corpore. The date is inferred from the facts that the latest philosophers mentioned in it were Posidonius and Asclepiades, and that Varro used it. The existence of the collection of Aëtius (De placitis, ![]()

![]() ) is attested by Theodoretus (Bishop of Cyrus), who mentions it as accessible, and who certainly used it, since his extracts are more complete and trustworthy than those of the Placita Philosophorum and Stobaeus. The compiler of the Placita was not Plutarch, but an insignificant writer of about the middle of the second century A.D., who palmed them off as Plutarch. Diels prints the Placita in parallel columns with the corresponding parts of the Eclogae, under the title of Aëtii Placita; quotations from the other writers who give extracts are added in notes at the foot of the page. So far as Cicero deals with the earliest Greek philosophy, he must be classed with the doxographers; both he and Philodemus (De pietate,

) is attested by Theodoretus (Bishop of Cyrus), who mentions it as accessible, and who certainly used it, since his extracts are more complete and trustworthy than those of the Placita Philosophorum and Stobaeus. The compiler of the Placita was not Plutarch, but an insignificant writer of about the middle of the second century A.D., who palmed them off as Plutarch. Diels prints the Placita in parallel columns with the corresponding parts of the Eclogae, under the title of Aëtii Placita; quotations from the other writers who give extracts are added in notes at the foot of the page. So far as Cicero deals with the earliest Greek philosophy, he must be classed with the doxographers; both he and Philodemus (De pietate, ![]() , fragments of which were discovered on a roll at Herculaneum) seem alike to have used a common source which went back to a Stoic epitome of Theophrastus, now lost.

, fragments of which were discovered on a roll at Herculaneum) seem alike to have used a common source which went back to a Stoic epitome of Theophrastus, now lost.

The greater part of the fragment of the Pseudo-Plutarchian ![]() given by Eusebius in Book I. 8 of the Praeparatio Evangelica comes from an epitome of Theophrastus, arranged according to philosophers. The author of the Stromateis, who probably belonged to the same period as the author of the Placita, that is, about the middle of the second century A.D., confined himself mostly to the sections de principio, de mundo, de astris; hence some things are here better preserved than elsewhere; cf. especially the notice about Anaximander.

given by Eusebius in Book I. 8 of the Praeparatio Evangelica comes from an epitome of Theophrastus, arranged according to philosophers. The author of the Stromateis, who probably belonged to the same period as the author of the Placita, that is, about the middle of the second century A.D., confined himself mostly to the sections de principio, de mundo, de astris; hence some things are here better preserved than elsewhere; cf. especially the notice about Anaximander.

The most important of the biographical doxographies is that of Hippolytus in Book I of the Refutation of all Heresies (the subtitle of the particular Book is ![]() ), probably written between 223 and 235 A.D. It is derived from two sources. The one was a biographical compendium of the

), probably written between 223 and 235 A.D. It is derived from two sources. The one was a biographical compendium of the ![]() type, shorter and even more untrustworthy than Diogenes Laertius, but containing excerpts from Aristoxenus, Sotion, Heraclides Lembus, and Apollodorus. The other was an epitome of Theophrastus. Hippolytus’s plan was to take the philosophers in order and then to pick out from the successive sections of the epitome of Theophrastus the views of each philosopher on each topic, and insert them in their order under the particular philosopher. So carefully was this done that the divisions of the work of Theophrastus can practically be restored.5 Hippolytus began with the idea of dealing with the chief philosophers only, as Thales, Pythagoras, Empedocles, Heraclitus. For these he had available only the inferior (biographical) source. The second source, the epitome of Theophrastus, then came into his hands, and, beginning with Anaximander, he proceeded to make a most precious collection of opinions.

type, shorter and even more untrustworthy than Diogenes Laertius, but containing excerpts from Aristoxenus, Sotion, Heraclides Lembus, and Apollodorus. The other was an epitome of Theophrastus. Hippolytus’s plan was to take the philosophers in order and then to pick out from the successive sections of the epitome of Theophrastus the views of each philosopher on each topic, and insert them in their order under the particular philosopher. So carefully was this done that the divisions of the work of Theophrastus can practically be restored.5 Hippolytus began with the idea of dealing with the chief philosophers only, as Thales, Pythagoras, Empedocles, Heraclitus. For these he had available only the inferior (biographical) source. The second source, the epitome of Theophrastus, then came into his hands, and, beginning with Anaximander, he proceeded to make a most precious collection of opinions.

Another of our authorities is Achilles (not Tatius), who wrote an Introduction to the Phaenomena of Aratus.6 Achilles’ date is uncertain, but he probably lived not earlier than the end of the second century A.D., and not much later. The foundation of Achilles’ commentary was a Stoic compendium of astronomy, probably by Eudorus, which in its turn was extracted from a work by Diodorus of Alexandria, a pupil of Posidonius. But Achilles drew from other sources as well, including the Pseudo-Plutarchian Placita; he did not hesitate to alter his extracts from the latter, and to mix alien matter with them.

The opinions noted by the Doxographi are largely incorporated in Diels’ later work Die Fragmente der Vorsokratiker.7

For the earlier period from Thales to Empedocles, Tannery gives a translation of the doxographic data and the fragments in his work Pour l’histoire de la science hellène, de Thalès à Empédocle, Paris, 1887; taking account as it does of all the material, this work is the best and most suggestive of the modern studies of the astronomy of the period. Equally based on the Doxographi, Max Sartorius’s dissertation Die Entwicklung der Astronomie bei den Griechen bis Anaxagoras und Empedokles (Halle, 1883) is a very concise and useful account. Naturally all or nearly all the material is also to be found in the monumental work of Zeller and in Professor Burnet’s Early Greek Philosophy (second edition, 1908); and picturesque, if sometimes too highly coloured, references to the astronomy of the ancient philosophers are a feature of vol. i of Gomperz’s Griechische Denker (third edition, 1911).

Eudemus of Rhodes (about 330 B.C.), a pupil of Aristotle, wrote a History of Astronomy (as he did a History of Geometry), which, is lost, but was the source of a number of notices in other writers. In particular, the very valuable account of Eudoxus’s and Callippus’s systems of concentric spheres which Simplicius gives in his Commentary on Aristotle’s De caelo is taken from Eudemus through Sosigenes as intermediary. A few notices from Eudemus’s work are also found in the astronomical portion of Theon of Smyrna’s Expositio rerum mathematicarum ad legendum Platonem utilium,8 which also draws on two other sources, Dercyllides and Adrastus. The former was a Platonist with Pythagorean leanings, who wrote a book on Plato’s philosophy. His date was earlier than the time of Tiberius, perhaps earlier than Varro’s. Adrastus, a Peripatetic of about the middle of the second century A.D., wrote historical and lexicographical essays on Aristotle; he also wrote a commentary on the Timaeus of Plato, which is quoted by Proclus as well as by Theon of Smyrna.

1 Gomperz, Griechische Denker, i3, p. 419.

2 Doxographi Graeci, ed. Diels, Berlin, G. Reimer, 1879.

3 Doxographi Graeci (henceforth generally quoted as D. G.), p. 151.

4 Cf. Günther in Windelband, Gesch. der alten Philosophie (Iwan von Müller’s Handbuch der klassischen Altertumswissenschaft, Band v. 1), 1894, p. 275.

5 Diels, Doxographi Graeci, p. 153.

6 Excerpts from this are preserved in Cod. Laurentian. xxviii. 44, and are included in the Uranologium of Petavius, 1630, pp. 121–64, &c.

7 Second edition in two vols, (the second in two parts), Berlin, 1906–10.

8 Edited by E. Hiller (Teubner, 1878).