IN order to obtain an accurate view of Plato’s astronomical system as a whole, and to judge of the value of his contributions to the advance of scientific astronomy, it is necessary, first, to collect and compare the various passages in his dialogues in which astronomical facts or theories are stated or indirectly alluded to; then, secondly, allowance has to be made for the elements of myth, romance, and idealism which are, in a greater or less degree depending on the character of the particular dialogue, invariably found as a setting and embellishment of actual facts and theories. When these elements are as far as possible eliminated, we find a tolerably complete and coherent system which, in spite of slight differences of detail and a certain development and even change of view between the earlier and the later dialogues, remains essentially the same.

In considering this system we have further to take into account Plato’s own view of astronomy as a science. This is clearly stated in Book VII of the Republic, where he is describing the curriculum which he deems necessary for training the philosophers who are to rule his State. The studies required are such as will lift up the soul from Becoming to Being; they should therefore have nothing to do with the objects of sensation, the changeable, the perishable, which are the domain of opinion only and not of knowledge. It is true that sensible objects are useful in so far as they give the stimulus to the purely intellectual discipline required, in so far, in fact, as they suffice to show that sensations are untrustworthy or even self-contradictory. Some objects of perception are adequately appreciated by the perception; these are non-stimulants; others arouse the intellect by showing that the mere perception produces an unsound result. Thus the perception which reports that a thing is hard frequently reports that it is also soft, and similarly with thickness and thinness, greatness and smallness, and the like. In such cases the soul is perplexed and appeals to the intellect for help; the intellect responds and looks at ‘great’ and ‘small’ (e.g.) as distinct and not confounded; we are thus led to the question what is the ‘great’ and what is the ‘small’ Science then is only concerned with realities independent of sense-perception; sensation, observation, and experiment are entirely excluded from it. At the beginning of the formulation of the curriculum for philosophers gymnastic and music are first mentioned, only to be rejected at once; gymnastic has to do with the growth and waste of bodies, that is, with the changeable and perishing; music is only the counterpart, as it were, of gymnastic. Next, all the useful arts are tabooed as degrading. The first subject of the curriculum is then taken, namely the science of Number, in its two branches of ![]()

![]() , dealing with the Theory of Numbers, as we say, and of

, dealing with the Theory of Numbers, as we say, and of ![]() , calculation, with the proviso that it is to be pursued for the sake of knowledge and not for purposes of trade. Next comes geometry, and here Plato, carrying his argument to its logical conclusion, points out that the true science of geometry is, in its nature, directly opposed to the language which, for want of better terms, geometers are obliged to use; thus they speak of ‘squaring’, ‘applying’ (a rectangle), ‘adding’, &c., as if the object were to do something, whereas the true purpose of geometry is knowledge. Geometrical knowledge is knowledge of that which is, not of that which becomes something at one moment and then perishes; and, as such, geometry draws the soul towards truth and creates the philosophic spirit which helps to raise up what we wrongly keep down. Astronomy is next mentioned, but Socrates corrects himself and gives the third place in the curriculum to stereometry, or solid geometry as we say, which, adding a third dimension, naturally follows plane geometry. And fourth in the natural order is astronomy, since it deals with the ‘motion of body’

, calculation, with the proviso that it is to be pursued for the sake of knowledge and not for purposes of trade. Next comes geometry, and here Plato, carrying his argument to its logical conclusion, points out that the true science of geometry is, in its nature, directly opposed to the language which, for want of better terms, geometers are obliged to use; thus they speak of ‘squaring’, ‘applying’ (a rectangle), ‘adding’, &c., as if the object were to do something, whereas the true purpose of geometry is knowledge. Geometrical knowledge is knowledge of that which is, not of that which becomes something at one moment and then perishes; and, as such, geometry draws the soul towards truth and creates the philosophic spirit which helps to raise up what we wrongly keep down. Astronomy is next mentioned, but Socrates corrects himself and gives the third place in the curriculum to stereometry, or solid geometry as we say, which, adding a third dimension, naturally follows plane geometry. And fourth in the natural order is astronomy, since it deals with the ‘motion of body’ ![]()

![]() , literally ‘motion of depth’ or of the third dimension).

, literally ‘motion of depth’ or of the third dimension).

When astronomy was first mentioned, Socrates’ interlocutor hastened to express approval of its inclusion, because it is proper, not only for the agriculturist and the sailor, but also for the general, to have an adequate knowledge of seasons, months, and years; whereupon Socrates rallies him upon his obvious anxiety lest the philosopher should be thought to be pursuing useless studies. When the speakers return to astronomy after the digression on solid geometry, Glaucon tries a different tack : at all events, he says, astronomy compels the soul to look upward and away from the things of the earth. But no ! he is using the term ‘upward’ in the sense of towards the material heaven, not, as Socrates had meant it, towards the realm of ideas or truth; and Socrates at once takes him up. On the contrary, he says, as it is now taught by those who would lead us upward to philosophy, it is calculated to turn the soul’s eye down.

‘You seem with sublime self-confidence to have formed your own conception of the nature of the learning which deals with the things above. At that rate, if a person were to throw his head back and learn something by contemplating a carved ceiling, you would probably suppose him to be investigating it, not with his eyes, but with his mind. You may be right, and I may be wrong. But I, for my part, cannot think any other study to be one that makes the soul look upwards except that which is concerned with the real and the invisible, and, if any one attempts to learn anything that is perceivable, I do not care whether he looks upwards with mouth gaping or downwards with mouth closed : he will never, as I hold, learn—because no object of sense admits of knowledge—and I maintain that in that case his soul is not looking upwards but downwards, even though the learner float face upwards on land or in the sea’ ‘I stand corrected’, said he; ‘your rebuke was just. But what is the way, different from the present method, in which astronomy should be studied for the purposes we have in view?’

‘This’, said I, ‘is what I mean. Yonder broideries in the heavens, forasmuch as they are broidered on a visible ground, are properly considered to be more beautiful and perfect than anything else that is visible; yet they are far inferior to those which are true, far inferior to the movements wherewith essential speed and essential slowness, in true number and in all true forms, move in relation to one another and cause that which is essentially in them to move : the true objects which are apprehended by reason and intelligence, not by sight. Or do you think otherwise?’ ‘Not at all’, said he. ‘Then’, said I, ‘we should use the broidery in the heaven as illustrations to facilitate the study which aims at those higher objects, just as we might employ, if we fell in with them, diagrams drawn and elaborated with exceptional skill by Daedalus or any other artist or draughtsman; for I take it that any one acquainted with geometry who saw such diagrams would indeed think them most beautifully finished but would regard it as ridiculous to study them seriously in the hope of gathering from them true relations of equality, doubleness, or any other ratio.’ ‘Yes, of course it would be ridiculous’, he said. ‘Then’, said I, ‘do you not suppose that one who is a true astronomer will have the same feeling when he looks at the movements of the stars? That is, will he not regard the maker of the heavens as having constructed them and all that is in them with the utmost beauty of which such works admit; yet, in the matter of the proportion which the night bears to the day, both these to the month, the month to the year, and the other stars to the sun and moon and to one another, will he not, think you, regard as absurd the man who supposes these things, which are corporeal and visible, to be changeless and subject to no aberrations of any kind; and will he not hold it absurd to exhaust every possible effort to apprehend their true condition?’ ‘Yes, I for one certainly think so, now that I hear you state it.’ ‘Hence’, said I, ‘we shall pursue astronomy, as we do geometry, by means of problems, and we shall dispense with the starry heavens, if we propose to obtain a real knowledge of astronomy, and by that means to convert the natural intelligence of the soul from a useless to a useful possession.’ ‘The plan which you prescribe is certainly far more laborious than the present mode of studying astronomy.’1

We have here, expressed in his own words, Plato’s point of view, and it is sufficiently remarkable, not to say startling. We follow him easily in his account of arithmetic and geometry as abstract sciences concerned, not with material things, but with mathematical numbers, mathematical points, lines, triangles, squares, &c, as objects of pure thought. If we use diagrams in geometry, it is only as illustrations; the triangle which we draw is an imperfect representation of the real triangle of which we think. And in the passage about the inconsistency between theoretic geometry and the processes of squaring, adding, &c, we seem to hear an echo of the general objection which Plato is said to have taken to the mechanical constructions used by Archytas, Eudoxus, and others for the duplication of the cube, on the ground that ‘the good of geometry is thereby lost and destroyed, as it is brought back to things of sense instead of being directed upward and grasping at eternal and incorporeal images’.2 But surely, one would say, the case would be different with astronomy, a science dealing with the movements of the heavenly bodies which we see. Not at all, says Plato with a fine audacity, we do not attain to the real science of astronomy until we have ‘dispensed with the starry heavens’, i.e. eliminated the visible appearances altogether. The passage above translated is admirably elucidated by Dr. Adam in his edition of the Republic.3 There is no doubt that Plato distinguishes two astronomies, the apparent and the real, the apparent being related to the real in exactly the same way as practical (apparent) geometry which works with diagrams is related to the real geometry. On the one side there are the visible broideries or spangles in the visible heavens, their visible movements and speeds, the orbits which they are seen to describe, and the number of hours, days, or months which they take to describe them. But these are only illustrations ![]() of real heavens, real spangles, real or essential speed or slowness, real or true orbits, and periods which are not days, months, or years, but absolute numbers. The broideries or spangles in both the astronomies are stars, but stars regarded as moving bodies. Essential speed and essential slowness seem to be, as Adam says, simply mathematical counterparts of visible stars, because they are said to be carried in the true motions of real astronomy, and therefore cannot be the speed and slowness of the mathematical bodies of which the visible stars are illustrations, but must be those mathematical bodies themselves. The true figures in which they move are their mathematical orbits, which we might now say are the perfect ellipses of which the orbits of the visible material planets are imperfect copies. And lastly, as a visible planet carries with it all the sensible properties and phenomena which it exhibits, so does its mathematical counterpart carry with it the mathematical realities which are in it. In short, Plato conceives the subject-matter of astronomy to be a mathematical heaven of which the visible heaven is a blurred and imperfect expression in time and space; and the science is a kind of ideal kinematics, a study in which the visible movements of the heavenly bodies are only useful as illustrations.

of real heavens, real spangles, real or essential speed or slowness, real or true orbits, and periods which are not days, months, or years, but absolute numbers. The broideries or spangles in both the astronomies are stars, but stars regarded as moving bodies. Essential speed and essential slowness seem to be, as Adam says, simply mathematical counterparts of visible stars, because they are said to be carried in the true motions of real astronomy, and therefore cannot be the speed and slowness of the mathematical bodies of which the visible stars are illustrations, but must be those mathematical bodies themselves. The true figures in which they move are their mathematical orbits, which we might now say are the perfect ellipses of which the orbits of the visible material planets are imperfect copies. And lastly, as a visible planet carries with it all the sensible properties and phenomena which it exhibits, so does its mathematical counterpart carry with it the mathematical realities which are in it. In short, Plato conceives the subject-matter of astronomy to be a mathematical heaven of which the visible heaven is a blurred and imperfect expression in time and space; and the science is a kind of ideal kinematics, a study in which the visible movements of the heavenly bodies are only useful as illustrations.

But, we may ask, what form would astronomical investigations on Plato’s lines have taken in actual operation? Upon this there is naturally some difference of opinion. One view is that of Bosanquet,4 who relies upon the phrase ‘we shall pursue astronomy as we do geometry by means of problems’, and suggests that the discovery of Neptune, picturesquely described by De Morgan as ‘Leverrier and Adams calculating an unknown planet into visible existence by enormous heaps of algebra’,5 is the kind of investigation which ‘seems just to fulfil Plato’s anticipations’. Plato was a master of method, and it is an attractive hypothesis to picture him as having at all events foreshadowed the methods of modern astronomy; but Adam seems to be clearly right in holding that the illustration does not fit the language of the passage in the Republic which we are discussing. For Plato says that the person who thought that the heavenly bodies should always move precisely in the same way and show no aberrations whatever would properly be thought ‘absurd’, and that it would be absurd to exhaust oneself in efforts to make out the truth about them; hence, on this showing, the visible perturbations of Uranus would scarcely have seemed to Plato very extraordinary or worth any very deep investigation by ‘heaps of algebra’ or otherwise. Besides, the discovery of Uranus’s perturbations could hardly have been made without observation, and observation is excluded by the words ‘we shall let the heavens alone’, The fact is that, at the time when our passage was written, Plato’s ‘problems’ were a priori problems which, when solved, would explain visible phenomena; Adams began at the other end, with observations of the phenomena, and then, when these were ascertained, sought for their explanation.

It may be that, when Plato is banning sense-perception from the science of astronomy in this uncompromising manner, he is consciously exaggerating; it would not be surprising if his enthusiasm and the strength of his imagination led him to press his point unduly. In any case, his attitude seems to have changed considerably by the time when he wrote the Timaeus and the Laws, both as regards the use made of sense-perception and the relation of astronomy to the visible heaven. In the Republic sense-perception is only regarded as useful up to the point at which, owing to its presentations contradicting one another, it stimulates the intellect. In the Timaeus the senses, e.g. sight, fulfil a much more important rôle. ‘Sight, according to my judgement, has been the cause of the greatest blessing to us, inasmuch as of our present discourse concerning the universe not one word would have been uttered had we never seen the stars and the sun and the heavens. But now day and night, being seen of us, and months and revolutions of years have made number, and they gave us the notion of time and the power of searching into the nature of the All; whence we have derived philosophy, than which no greater good has come nor shall come hereafter as the gift of the gods to mortal man. This I declare to be the chiefest blessing due to the eyes.’6 In the Laws Plato makes the Athenian stranger say that it is impious to use the term ‘planets’ of the gods in heaven as if they and the sun and moon never kept to one uniform course, but wandered hither and thither; the case is absolutely the reverse of this, ‘for each of these bodies follows one and the same path, not many paths but one only, which is a circle, although it appears to be borne in many paths.’7 Here then we no longer have the view that the visible heavenly bodies should be neglected as being subject to perturbations which it would be useless to attempt to fathom, and that true astronomy is only concerned with the true heavenly bodies of which they are imperfect copies; but we are told that the paths of the visible sun, moon, and planets are perfectly uniform, the only difficulty being to grasp the fact. Bosanquet observes, on the passage in the Republic contrasting the visible and the true heavens, that’ Plato’s point is that there are no doubt true laws by which the periods, orbits, accelerations and retardations of the solids in motion can be explained, and that it is the function of astronomy to ascertain them’.8 On the later view stated in the Laws this would be true with ‘the visible heavenly bodies’ substituted for ‘solids in motion’.

We are told on the authority of Sosigenes,9 who had it from Eudemus, that Plato set it as a problem to all earnest students to find ‘what are the uniform and ordered movements by the assumption of which the apparent movements of the planets can be accounted for’, The same passage says that Eudoxus was the first to formulate hypotheses with this object; Heraclides of Pontus followed with an entirely new hypothesis. Both were pupils of Plato, and it is a fair inference that the stimulus of the Master’s teaching was a factor contributing to these great advances, although it is probable that Eudoxus attacked the problem on his own initiative.

When we come to extract from the different dialogues the details of Plato’s astronomical system, we find, as already indicated, that, if allowance is made for the differences in the literary form in which they are presented, and for the greater or less admixture of myth, romance, and poetry, the successive presentations of the system at different periods of Plato’s life merely show different stages of development; the system remains throughout fundamentally the same. Some of the passages have nothing mythical about them at all; e.g. the passage in the Laws, which is intended to combat prevailing errors, gives a plain statement of the view which Plato thought the most correct. In the passages in which myth has a greater or less share, that which constitutes the most serious part is precisely that which relates to astronomy; and that which proves that the astronomical part is serious is the fact that, in different forms, and with more or fewer details in different passages, we have only one and the same main hypothesis; the variations are on points which are merely accessory.10 Nor was the system revolutionary as compared with previous theories; on the contrary, Plato evidently selected what appeared to him to be the best of the astronomical theories current in his time, and only made corrections which his inexorable logic and his scientific habit of mind could not but show to be necessary; and the theory which commended itself to him the most was that of Pythagoras and the early Pythagoreans—the system in which the earth was at rest in the centre of the universe—as distinct from that of the later Pythagorean school, with whom the earth became a planet revolving like the others about the central fire.

Plato’s system is set out in its most complete form in the Timaeus, and on this ground Martin, in his last published memoir on the subject, began with the exposition in the Timaeus and then added, for the purpose of comparison, the substance of the astronomical passages in the other dialogues. This plan would perhaps enable a certain amount of repetition to be avoided; but I think that the development of the system is followed better if the usual plan is adopted and the dialogues taken in chronological order.

We begin therefore with the Phaedrus, perhaps the earliest of all the dialogues. The astronomy in the Phaedrus consists only in the astronomical setting of the myth about souls soaring in the heaven and then again falling to earth. Soaring in the heaven, they with difficulty keep up for a time with the chariots of the gods in their course round the heavens.

‘Zeus, the great captain in heaven, mounted on his winged chariot, goes first and disposes and oversees all things. Him follows the army of Gods and Daemons ordered in eleven divisions; for Hestia alone abides in the House of God, while, among the other gods, those who are of the number of the twelve and are appointed to command lead the divisions to which they were severally appointed.

Many glorious sights are there of the courses in the heaven traversed by the race of blessed gods, as each goes about his own business; and whosoever wills, and is able, follows, for envy has no place among the Heavenly Choir . . .

The chariots of the gods move evenly and, being always obedient to the hand of the charioteer, travel easily; the others travel with great difficulty . . .

The Souls which are called immortal, when they are come to the summit of the Heaven, go outside and stand on the roof and, as they stand, they are carried round by its revolution and behold the things which are outside the Heaven’.11

Here, then, the army of Heaven is divided into twelve divisions. One is commanded by Zeus, the supreme God, who also commands-in-chief all the other divisions as well; subject to this, each division has its own commander. Zeus is here the sphere of the fixed stars, which revolves daily from east to west and carries round with it the other divisions except one, Hestia, which abides unmoved in the middle. Hestia, the Hearth in God’s House, stays at home to keep house; the other divisions follow the march of Zeus but perform separate evolutions under the command of their several leaders. Hestia is here undoubtedly the earth, unmoved in the centre of the world,12 and is not the central fire of the Pythagoreans. The gods in command of the ten other divisions are, in the first place, the seven planets, i. e. the sun and moon and the five planets, and then between them and the earth come the three others which are the aether, the air, and the moist or water.13 The sun, moon, and planets are all carried round in the general revolution of the whole heaven from east to west, but have independent duties and commands of their own, i.e. separate movements which (as later dialogues will tell us) are movements in the opposite sense, i. e. from west to east

In the Phaedo Plato puts into the mouth of Socrates his views as to the shape of the earth, its position and its equilibrium in the middle of the universe. The first passage on the subject is that in which he complains of the inadequate use by Anaxagoras of his Nous in explaining phenomena.

‘When once I heard some one reading from a book, as he said, of Anaxagoras, in which the author asserts that it is Mind which disposes and causes all things, I was pleased with this cause, as it seemed to me right in a certain way that Mind should be the cause of all things, and I thought that, if this is so, and Mind disposes everything, it must place each thing as is best. . . . With these considerations in view I was glad to think that I had found a guide entirely to my mind in this matter of the cause of existing things, I mean Anaxagoras, and that he would first tell me whether the earth is flat or round, and, when he had told me this, would add to it an explanation of the cause and the necessity for it, which would be the Better, that is to say, that it is better that the earth should be as it is; and further, if he should assert that it is in the centre, that he would add, as an explanation, that it is better that it should be in the centre. . . . Similarly I was prepared to be told in like manner, with regard to the sun, the moon, and the other stars, their relative speeds, their turnings or changes, and their other conditions, in what way it is best for each of them to exist, to act, and to be acted upon so far as they are acted upon. For I should never have supposed that, when once he had said that these things were ordered by Mind, he would have assigned to them in addition any cause except the fact that it is best that they should be as they are. . . . From what a height of hope then was I hurled down when I went on with my reading and saw a man that made no use of Mind for ordering things, but assigned as their cause airs, aethers, waters, and any number of other absurdities’, [Then follows the sentence stating that it is as if one were to say that Socrates did everything he did by Mind and then gave as the cause of his sitting there the fact that his body was composed of bones and sinews, the former having joints, and the sinews serving to bend and stretch out the limbs consisting of the bones with their covering sinews and flesh and skin, and so on. This inability to distinguish between what is the cause of that which is and the indispensable conditions without which the cause cannot be a cause suggests that most people are fumbling in the dark.] ‘Thus it is that one makes the earth remain stationary under the heaven by making it the middle of a vortex, another sets the air as a support to the earth, which is like a flat kneading-trough.’14

The last sentence alludes to some of the familiar early views as to the form of the earth. Only Parmenides and the Pythagoreans thought it to be spherical, the Ionians and others supposed it to be flat, though differing as to details; the theory that it is the motion of a vortex with the earth in the middle that keeps it stationary is that of Empedocles, while the idea that it is a disc, or like a flat kneading-trough, supported by air, is of course that which Aristotle attributes to Anaximenes, Anaxagoras, and Democritus.15

Plato’s own view is stated later in the dialogue.

‘There are many and wondrous regions in the earth, and it is neither in its nature nor in its size what it is supposed to be by those whom we commonly hear speak about it; of this I have been convinced, I will not say by whom. . . . My persuasion as to the form of the earth and the regions within it I need not hesitate to tell you . . . I am convinced then, said he, that, in the first place, if the earth, being a sphere, is in the middle of the heaven, it has no need either of air or of any other such force to keep it from falling, but that the uniformity of the substance of the heaven in all its parts and the equilibrium of the earth itself suffice to hold it; for a thing in equilibrium in the middle of any uniform substance will not have cause to incline more or less in any direction, but will remain as it is, without such inclination. In the first place I am persuaded of this.’16

When Socrates says he has been convinced by some one of the fact that the earth is different from what it was usually supposed to be, he is considered by some to be referring to Anaximander who drew the first map of the inhabited earth. But surely Anaximander’s views, no doubt with improvements, would be represented in those of his successors, the geographers of the time, whom Socrates considers to be wrong (we are told, for instance, that Democritus, who, like Anaximander, thought the earth flat, compiled a geographical and nautical survey of the earth17). ‘Some one’ may possibly be no one in particular, in accordance with Plato’s habit of ‘giving an air of antiquity to his fables by referring them to some supposititious author’.18 On the other hand, the explanation of the reason why the spherical earth remains in equilibrium in the centre of the universe, namely that there is nothing to make it move one way rather than another, is sufficiently like Anaximander’s explanation of the same thing.19

Socrates proceeds :

‘Moreover, I am convinced that the earth is very great, and that we who live from the river Phasis as far as the Pillars of Heracles inhabit a small part of it; like to ants or frogs round a pool, so we dwell round the sea; while there are many other men dwelling elsewhere in many regions of the same kind. For everywhere on the earth’s surface there are many hollows of all kinds both as regards shapes and sizes, into which water, clouds, and air flow and are gathered together; but the earth itself abides pure in the purity of the heaven, in which are the stars, the heaven which the most part of those who use to speak of these things call aether, and it is the sediment of the aether which, in the forms we mentioned, is always flowing and being gathered together in the hollow places of the earth. We then, dwelling in the hollow parts of it, are not aware of the fact but imagine that we dwell above on its surface; this is just as if any one dwelling down at the bottom of the sea were to imagine that he dwelt on its surface and, beholding the sun and the other heavenly bodies through the water, were to suppose the sea to be the heaven, for the reason that, through being sluggish and weak, he had never yet risen to the top of the sea nor been able, by putting forth his head and coming up out of the sea into the place where we live, to see how much purer and more beautiful it is than his abode, neither had heard this from another who had seen it. We are in the same case; for, though dwelling in a hollow of the earth, we think we dwell upon its surface, and we call the air heaven as though this were the heaven and through this the stars moved, whereas in fact we are through weakness and sluggishness unable to pass through and reach the limit of the air; for, if any one could reach the top of it or could get wings and fly up, then, just as fishes here, when they come up out of the sea, espy the things here, so he having come up, would likewise descry the things there, and if his strength could endure the sight would know that there is the true heaven, the true light, and the true earth. For here the earth, with its stones and the whole place where we are, is corrupted and eaten away, as things in the sea are eaten away by the salt, insomuch that there grows in the sea nothing of moment nor anything perfect, so to speak, but there are hollow rocks, sand, clay without end. and sloughs of mire wherever there is also earth, things not worthy at all to be compared to the beautiful objects within our view; but the things beyond would appear to surpass even more the things here.’20. . .

Then begins the myth of the things which are upon the real earth and under the heaven,

‘First it is said that, if one saw it from above, the earth is like unto a ball made with twelve stripes of different colours, each stripe having its own colour. . . .’

We need not pursue the picture of the idealized earth with its varied hues, its precious stones, its race of men excelling us in sight, hearing, and intelligence in the same proportion as air excels water, and aether excels air, in purity, and so on.

Reading the story of the hollows in the earth, we recall the idea of Archelaus, which he perhaps learnt from Anaxagoras, that the earth was hollowed out in the middle but higher at the edges. This shape would correspond to the flat kneading-trough mentioned by Plato as the form given by some to the earth.21 Plato, realizing that certain inhabited regions such as that from the river Phasis (descending from the Caucasus into the Black Sea) to the Pillars of Hercules, being partly bounded by mountains, did appear to be hollows, had to reconcile this fact with his earnest conviction of the earth’s sphericity. Archelaus regarded the whole earth as one such hollow; to which Plato replies that the inhabited earth may be a hollow, but it is not the whole earth. The earth itself is very large indeed, so that the apparent hollow formed by the portion in which we live is quite a small portion of the whole. There are any number of other hollows of all sorts and sizes; these hollows are separated by the ridges between them, and it is only the tops of these ridges that are on the real surface of the spherical earth. Consequently there is nothing in the existence of the hollows that is inconsistent with the earth being spherical; they are mere indentations. The impossibility of our climbing up the sides to the top of the bounding ridges, or taking wings and flying out of the hollows, and so reaching the real surface of the earth and obtaining a view of the real heavens, is of course poetic fancy and has nothing to do with astronomy.

The extreme estimate of the size of the earth made by Plato in the Phaedo seems to be peculiar to him. For the sake of contrast, Aristotle’s remarks on the same subject may be referred to.22 Aristotle says that observations of the stars show not only that the earth is spherical, but that it is ‘not great’. For quite a small change of position from north to south or vice versa involves a change of the circle of the horizon. Thus some stars are seen in Egypt and Cyprus which are not seen in the northern regions, and some stars which in the northern regions are always above the horizon are, in Egypt, seen to rise and set. Such differences for so small a change in the position of an observer would not be possible unless the earth’s sphere were of quite moderate size. Aristotle adds that the mathematicians of his day who tried to calculate the circumference of the earth made it approach 400,000 stades. This estimate had, according to Archimedes,23 been reduced in his time to 300,000 stades, and Eratosthenes made the circumference to be 252,000 stades on the basis of a definite measurement of the arc separating Syene and Alexandria on the same meridian, compared with the known distance between those places.

On the negligibility of the height of the highest mountain in comparison with the diameter of the earth, Theon of Smyrna24 has some remarks based on the estimates of 252,000 stades for the circumference and of 10 stades (a low estimate, it is true) for the height of the highest mountain above the general level of the plains.

Coming now to the Republic, Book X, we get a glimpse of a more complete system, though again the astronomy is blended with myth. The story is that of Er, the son of Armenius, who, after being killed in battle, came to life twelve days afterwards and recounted what he had seen. He first came with other souls to a mysterious place where there were two pairs of mouths, one pair leading up into heaven, the other two down into the earth; between them sat judges who directed the righteous to take the road to the right hand leading up into the heaven and sent those who had wrought evil down the left-hand road into the earth; at the same time other souls were returning by the other road out of the earth, and others again by the other road coming down from the heaven : the two returning streams met, the former travel-stained after a thousand years’ journeying under the earth, the latter returning pure from heaven, and they foregathered in the meadow where they related their several experiences.

‘Now when seven days had passed since the spirits arrived in the meadow, they were compelled to arise on the eighth day and journey thence; and on the fourth day they arrived at a point from which they saw extended from above through the whole heaven and earth a straight light, like a pillar, most like to the rainbow, but brighter and purer. This light they reached when they had gone forward a day’s journey, and there, at the middle of the light, they saw, extended from heaven, the extremities of the chains thereof; for this light it is which binds the heaven together, holding together the whole revolving firmament as the undergirths hold together triremes; and from the extremities they saw extended the Spindle of Necessity by which all the revolutions are kept up. The shaft and hook thereof are made of adamant, and the whorl is partly of adamant and partly of other substances.

Now the whorl is after this fashion. Its shape is like that we use; but from what he said we must conceive of it as if we had one great whorl, hollow and scooped out through and through, into which was inserted another whorl of the same kind but smaller, nicely fitting it, like those boxes which fit into one another; and into this again we must suppose a third whorl fitted, into this a fourth, and after that four more. For the whorls are altogether eight in number, set one within another, showing their rims above as circles and forming about the shaft a continuous surface as of one whorl; while the shaft is driven right through the middle of the eighth whorl.

The first and outermost whorl has the circle of its rim the broadest, that of the sixth is second in breadth, that of the fourth is third, that of the eighth is fourth, that of the seventh is fifth, that of the fifth is sixth, that of the third is seventh, and that of the second is eighth. And the circle of the greatest is of many colours, that of the seventh is brightest, that of the eighth has its colour from the seventh which shines upon it, that of the second and fifth are like each other and yellower than those aforesaid, the third is the whitest in colour, the fourth is pale red, and the sixth is the second in whiteness.

The Spindle turns round as a whole with one motion, and within the whole as it revolves the seven inner circles revolve slowly in the opposite sense to the whole, and of these the eighth goes the most swiftly, second in speed and all together go the seventh and sixth and fifth, third in the speed of its counter-revolution the fourth appears to move, fourth in speed comes the third, and fifth the second. And the whole Spindle turns in the lap of Necessity.

Upon each of its circles above stands a Siren, carried round with it and uttering one single sound, one single note, and out of all the notes, eight in number, is formed one harmony.

And again, round about, sit three others at equal distances apart, each on a throne, the daughters of Necessity, the Fates, clothed in white raiment and with garlands on their heads, Lachesis, Clotho, and Atropos, and they chant to the harmony of the Sirens, Lachesis the things that have been, Clotho the things that are, and Atropos the things that shall be.

And Clotho at intervals with her right hand takes hold of the outer revolving whorl of the Spindle and helps to turn it; Atropos with her left hand does the same to the inner whorls; Lachesis with both hands takes hold of the outer and inner alternately (i.e. of the outer with her right hand and of the inner with her left).’25

On the precise interpretation of the details of this description there has been a great deal of discussion and difference of opinion.26 Some of the details are hardly astronomical, and this is not the place for more than a short statement of the principal points at issue.

First, what is the form and position of the ‘straight light, like a pillar’, and at what point is ‘the middle’ of the light where the souls saw ‘the extremities of the chains’ binding the heavens together? As early as Proclus‘s time one supposition was that the light was the Milky Way.27 Proclus rejected this view, which in modern times is represented by Boeckh28 and Martin.29 Boeckh supposes the souls to be beyond the north pole, outside the circle of the Milky Way which, if seen from the outside edgeways, would look straight; the middle of the light is for him the north pole, from which stretch the chains of heaven, one of which is the light. Martin makes the souls see the Milky Way as a straight column of light from below; thence they go quickly up in the day’s journey to the middle of the light (Martin compares the souls in Phaedrus 247 B–248 B, which get to the outside of the sphere of the fixed stars); they there see both poles of the sphere, and the curved column is, for them, like a band forming a complete ring round the sphere and holding it together; this curved column can only be the Milky Way. Martin supports his view by pressing the comparison of the column to a rainbow, which, he says, must refer to its form and not to its colours; and for the illusion of supposing the curved column to be straight he cites the parallel of Xenophanes, who thought the stars moved in straight lines which only appeared to be circles. I agree with Adam’s opinion that to suppose the column to be curved and only to appear straight does violence to the language of Plato. Then again, it would be strange that the souls, one class of which has come back from a thousand years’ journey in the heaven, and the other from the same length of journey under the earth, should next be taken up, all of them, to the top of the heavenly sphere; there is nothing to suggest that, either in the four days elapsing between the time when they leave the meadow and the time when they first see the straight column of light, or in the one day following which brings them to the middle of the light, they leave the earth at all. The other alternative is to take the ‘straight light’ to be, in accordance with the natural meaning of the words, a straight line or straight cylindrical column of light passing from pole to pole right through the centre of the universe and of the earth (occupying the centre of the universe), which column of light symbolizes the axis on which the sphere of the heaven revolves. Where then is ‘the middle’ of this column of light which the souls are supposed to reach one day after they first see the column? Adam thinks it can only be at the centre of the earth, and he seems to base this view mainly on the fact that, later on, the souls, after passing under the throne of Necessity and encamping by the river of Unmindfulness in the plain of Lethe, are said (621 B) to go up, ‘shooting like stars’, to be born again. Here also I cannot but think it strange that all the souls should be brought down to the centre of the earth, seeing that one class of them had just returned from a thousand years’ wandering in the interior of the earth, to say nothing of the shortness of the time allowed for reaching the centre of the earth, namely, one day from the time when they first saw the column of light, while there is nothing in the language describing the five days’ journey to suggest that they did anything but walk ![]() . Now the place of the judgement-seat which was between the mouths of the earth and the heaven, and to which the souls returned after their thousand years in the earth and heaven respectively, was on the surface of the earth; presumably therefore the meadow to which they turned aside from that place was also on the surface of the earth (and not even on the surface of the ‘True Earth’ of the Phaedo, as Adam supposes); and Mr. J. A. Stewart30 has pointed out that the popular belief as to the river Lethe made it a river entirely above ground and not one of the rivers of Tartarus. Hence I am disposed to agree with Mr. Stewart that the whole journey from the meadow by the throne of Necessity to the plain of the river Lethe was along the surface of the earth. Although Adam rightly rejects Boeckh’s identification of the ‘straight light’ with the Milky Way, he is induced by the parallel of the ‘undergirths’

. Now the place of the judgement-seat which was between the mouths of the earth and the heaven, and to which the souls returned after their thousand years in the earth and heaven respectively, was on the surface of the earth; presumably therefore the meadow to which they turned aside from that place was also on the surface of the earth (and not even on the surface of the ‘True Earth’ of the Phaedo, as Adam supposes); and Mr. J. A. Stewart30 has pointed out that the popular belief as to the river Lethe made it a river entirely above ground and not one of the rivers of Tartarus. Hence I am disposed to agree with Mr. Stewart that the whole journey from the meadow by the throne of Necessity to the plain of the river Lethe was along the surface of the earth. Although Adam rightly rejects Boeckh’s identification of the ‘straight light’ with the Milky Way, he is induced by the parallel of the ‘undergirths’ ![]() of triremes to assume, in addition to the straight light forming the axis of the universe, a circular ring of light passing round it from pole to pole and joining the straight portion at the poles;31 this he does because the more proper meaning of ‘undergirths’ appears to be ropes passed round the vessel outside it and horizontally, rather than planks passing longitudinally from stem to stern as Proclus and others supposed.32 But there is nothing in the Greek to suggest the addition of this circle to the straight light; and the assumption seems, as Mr. Stewart says,33 to make too much of the man-of-war or trireme. Moreover, the ground for assuming a ring, as well as a straight line, of light vanishes altogether if the

of triremes to assume, in addition to the straight light forming the axis of the universe, a circular ring of light passing round it from pole to pole and joining the straight portion at the poles;31 this he does because the more proper meaning of ‘undergirths’ appears to be ropes passed round the vessel outside it and horizontally, rather than planks passing longitudinally from stem to stern as Proclus and others supposed.32 But there is nothing in the Greek to suggest the addition of this circle to the straight light; and the assumption seems, as Mr. Stewart says,33 to make too much of the man-of-war or trireme. Moreover, the ground for assuming a ring, as well as a straight line, of light vanishes altogether if the ![]() are, after all, cables stretched tight, i.e. in straight lines, inside the ship from stem to stern, as Tannery holds.34 It seems to be enough to regard Plato as saying that the pillar (which alone is mentioned) holds the universe together in its particular way as the undergirths do the trireme in their way. I prefer then to believe that the light is simply a straight column or cylinder of light, and that the ‘middle of the light’ is the point on the surface of the earth which is in the centre of the column of light, i.e. the centre of the circular projection of the cylinder of light on the earth’s surface. I do not see why the souls, looking from that point along the cylinder of light in both directions, should not in this way be supposed to see (illuminated by the column as by a searchlight) the poles of the universe, nor why these should not be called the extremities of the chains holding the heaven together, the pillar of light having by a sudden change of imagery become those chains themselves.

are, after all, cables stretched tight, i.e. in straight lines, inside the ship from stem to stern, as Tannery holds.34 It seems to be enough to regard Plato as saying that the pillar (which alone is mentioned) holds the universe together in its particular way as the undergirths do the trireme in their way. I prefer then to believe that the light is simply a straight column or cylinder of light, and that the ‘middle of the light’ is the point on the surface of the earth which is in the centre of the column of light, i.e. the centre of the circular projection of the cylinder of light on the earth’s surface. I do not see why the souls, looking from that point along the cylinder of light in both directions, should not in this way be supposed to see (illuminated by the column as by a searchlight) the poles of the universe, nor why these should not be called the extremities of the chains holding the heaven together, the pillar of light having by a sudden change of imagery become those chains themselves.

By another sudden change of imagery the chains following the course of the pillar of light become a spindle which is similarly extended from the same ‘extremities’ or poles, and the spindle with its whorls representing the movements of the universe is seen to turn in the lap of Necessity. The throne of Necessity must on the above view be at the point on the surface of the earth which is in the middle of the column of light; and on this hypothesis, as on others, the attempt to translate the details of the poetic imagery into a self-consistent picture of physical facts is hopeless, for the simple reason that one thing cannot both be entirely outside another thing and entirely within it at the same time. Let us assume with Boeckh that the souls are outside the universe when they see the apparently straight light; Necessity will then presumably be outside the universe which in the form of the spindle and whorls she holds in her lap. It is on this assumption impossible to give an intelligible meaning to ‘under the throne of Necessity’ as an intermediate point on the journey of the souls from the meadow to the plain of Lethe. The same difficulty arises if, with Zeiler, we suppose Plato to be availing himself of the external Necessity which, according to Aëtius, Pythagoras regarded as ‘surrounding the world’35 Plato’s Necessity is certainly not outside but in the middle. If, however, Necessity sits either at the centre of the earth as supposed by Adam, or at a point on the surface of the earth as supposed by Mr. Stewart, how can she, being inside the universe, hold the spindle and whorls forming the universe in her lap? This is no doubt the difficulty which makes Mr. Stewart infer that Necessity does not hold the universe itself in her lap, but a model of the universe.36

The real astronomy of the Republic is contained in the description of the whorls and their movements. The first question arising is, what was the shape of the whorls? They are not spheres because they have rims (‘lips’, ![]() ) one inside the other, which are all visible and form one continuous flat surface as of one whorl. We might, on the analogy of Parmenides’ bands, suppose that they are zones of hollow spheres symmetrical about a great circle, i.e. so placed that the plane of the great circle is parallel to, and equidistant from, the outer circles bounding the zones. Adam supposes them to be hemispheres, which Plato possibly obtained by cutting in half the Pythagorean spheres mentioned by Theon of Smyrna.37 It is true that there is nothing in the text of Plato requiring them to be hemispheres, although Proclus regards them as segments of spheres38; but the supposition that they are hemispheres has the great advantage that it eliminates all question of the depth of the whorls measured perpendicularly (downwards, let us say) from the visible flat surface formed by their rims. Plato says nothing of the depth of the whorls, but merely gives the rims different breadths. The moment we suppose the whorls to be zones or rings we have to consider what depth or thickness (i.e. perpendicular distance between the two bounding surfaces) must be assigned to them. The thickness of the rings would presumably be great enough to hold symmetrically the largest of the heavenly bodies which the rings carry round with them.39 Martin40 takes the thickness of the rings to be greater than this; he supposes that the outer whorl is an equatorial zone of the celestial sphere included between two equal circular sections ‘which are doubtless the tropics’. But Martin admits that there is, in the whole passage, no reference to any obliquity of movements relatively to the equator, and he can only suppose such obliquity to be tacitly implied by the thickness of each whorl. I think that this supposition is unsafe, and that it is better to assume that, at this stage in the development of his astronomy, or perhaps merely for the purpose of the imagery of this particular myth, Plato did not recognize any obliquity, still less any variations of obliquity in the movements of the planets.41 I prefer therefore to suppose the whorls to be hemispheres, or similar segments of spheres fitting one inside the other, and having their bases in one plane. The planets, sun, and moon would perhaps be regarded as fixed in such a position that their centres would be on the plane surface which is the common boundary of all the whorls, so that half of each planet would project above that surface and half of it would be below.

) one inside the other, which are all visible and form one continuous flat surface as of one whorl. We might, on the analogy of Parmenides’ bands, suppose that they are zones of hollow spheres symmetrical about a great circle, i.e. so placed that the plane of the great circle is parallel to, and equidistant from, the outer circles bounding the zones. Adam supposes them to be hemispheres, which Plato possibly obtained by cutting in half the Pythagorean spheres mentioned by Theon of Smyrna.37 It is true that there is nothing in the text of Plato requiring them to be hemispheres, although Proclus regards them as segments of spheres38; but the supposition that they are hemispheres has the great advantage that it eliminates all question of the depth of the whorls measured perpendicularly (downwards, let us say) from the visible flat surface formed by their rims. Plato says nothing of the depth of the whorls, but merely gives the rims different breadths. The moment we suppose the whorls to be zones or rings we have to consider what depth or thickness (i.e. perpendicular distance between the two bounding surfaces) must be assigned to them. The thickness of the rings would presumably be great enough to hold symmetrically the largest of the heavenly bodies which the rings carry round with them.39 Martin40 takes the thickness of the rings to be greater than this; he supposes that the outer whorl is an equatorial zone of the celestial sphere included between two equal circular sections ‘which are doubtless the tropics’. But Martin admits that there is, in the whole passage, no reference to any obliquity of movements relatively to the equator, and he can only suppose such obliquity to be tacitly implied by the thickness of each whorl. I think that this supposition is unsafe, and that it is better to assume that, at this stage in the development of his astronomy, or perhaps merely for the purpose of the imagery of this particular myth, Plato did not recognize any obliquity, still less any variations of obliquity in the movements of the planets.41 I prefer therefore to suppose the whorls to be hemispheres, or similar segments of spheres fitting one inside the other, and having their bases in one plane. The planets, sun, and moon would perhaps be regarded as fixed in such a position that their centres would be on the plane surface which is the common boundary of all the whorls, so that half of each planet would project above that surface and half of it would be below.

It is not difficult to see what is the astronomical equivalent of each of the concentric whorls. The outermost (the first) represents the sphere of the fixed stars; and here we have somewhat the same difficulty as we saw in the case of Parmenides’ wreaths or bands. The fixed stars being spread over the whole sphere, how can that sphere be represented by a hemisphere, or a segment of a sphere, or a ring or zone? The answer is presumably that the whorls are pure mechanism, designed with reference to the necessity of making the movements of the inner whorls give plane circular orbits to the seven single heavenly bodies, the sun, the moon, and the five planets. Mr. Stewart, in accordance with his idea that it is a model which Necessity holds in her lap, suggests that the model might be an old-fashioned one with rings instead of spheres, or that, if it were an up-to-date model, with spheres, it might be one in which only the half of each sphere was represented so that the internal ‘works’ might be seen; he compares the passage in the Timaeus42 where the speaker says that, without the aid of a model of the heavens, it would be useless to attempt to describe certain motions.

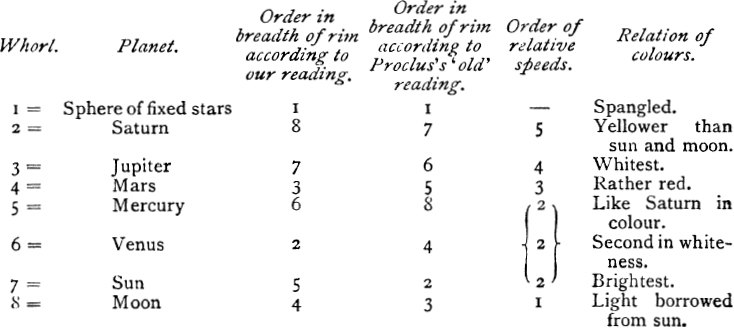

The second whorl (reckoning from the outside) carries the planet Saturn, the third Jupiter, the fourth Mars, the fifth Mercury, the sixth Venus, the seventh the sun, and the eighth the moon. The earth, as always in Plato, is at rest in the centre of the system. The outer rim of each whorl clearly represents the path of the heavenly body which that whorl carries. The breadth of each whorl, that is, the difference between the radii of its outer and inner rims respectively (the inner radius of the particular whorl being of course the outer radius of the next smaller whorl), is the difference between the distances from the earth of the planet carried by the particular whorl and of the planet carried by the next smaller whorl. The rim of the innermost whorl (the eighth) is the orbit of the moon, the outer rim of the next whorl (the seventh) is the orbit of the sun, and so on. Proclus43 says that there was an earlier reading of the passage about the breadths of the rims of the successive whorls which made them dependent on, i.e. presumably proportional to, the sizes of the successive planets. Professor Cook Wilson observes that ‘this principle would be a sort of equable distribution of planetary mass, allowing the greater body more space. It would come to allowing the same average of linear dimension of planetary mass to each unit of distance between orbits throughout the system.’44 Adam, however, for reasons which he gives, decides in favour of our reading of the passage as against the ‘earlier’ reading of Proclus.

As regards the speeds we are told that, while the outermost whorl (the sphere of the fixed stars) and the whole universe (including the inner whorls) along with it are carried round in one motion of rotation in one direction (i.e. from east to west), the seven inner whorls have slow rotations of their own in addition, the seven rotations being at different speeds but all in the opposite sense to the rotation of the whole universe. Hence the quickest rotation is that of the fixed stars and the whole universe, which takes place once in about 24 hours; the slower speeds of the rest are speeds which are not absolute but relative to the sphere of the fixed stars regarded as stationary, and of these relative speeds the quickest is that of the moon, the next quickest that of the sun, Venus, and Mercury, which travel in company with one another, i.e. have the same angular velocity and take about a year to describe their orbits respectively; the next is that of Mars, the next that of Jupiter, and the last and slowest relative motion is that of Saturn. The speeds here are all angular speeds because, if the sun, Venus, and Mercury describe their several orbits in the same time, the sun must have the least linear velocity of the three, Venus the next greater, and Mercury the greatest, since the actual length of the orbit of the sun is less than that of the orbit of Venus, and the length of the orbit of Venus is again less than that of the orbit of Mercury. To obtain the absolute angular speeds in the direction of the daily rotation, i. e. from east to west, we have to deduct from the speed of the daily rotation the slower relative speeds of the respective planets in the opposite sense; the absolute angular speeds are therefore, in descending order, as follows :

Sphere of fixed stars, Saturn, Jupiter, Mars,  , Moon.

, Moon.

The following table gives the order of orbital distances, or breadths of rims of whorls, as compared with the order of the whorls themselves, the order of relative speeds, and the relation of the colours of the planets respectively :

As, according to either reading, Plato only gives the order of the successive rims as regards breadth, not the ratios of their breadths, we cannot gather from this passage what was his view as to the ratios of the distances of the respective heavenly bodies from the earth. Nor can his estimate of the ratios be deduced from the mere allusion to the harmony produced by the eight notes chanted by the Sirens perched upon the respective whorls; as to this harmony see pp. 105–15 above.

As regards the Sirens, Theon of Smyrna tells us that some supposed them to be the planets themselves; some, however, regarded them as representing the several notes which were produced by the motion of the several stars at their different speeds.45 It is clear that the latter is the right view; the Sirens are a poetical expression of the notes.

It will be noticed that Plato has the correct theory with regard to the moon’s light being derived from the sun, a fact which, as before stated, he evidently learned from Anaxagoras.

The Timaeus is one of the latest of Plato’s dialogues and is the most important of all for our purpose because in it Plato’s astronomical system is most fully developed and given with the fewest lacunae. I shall continue to follow the plan of quoting passages in Plato’s own words and adding the explanations which appear necessary. First, we are told that the universe is one only, eternal, alive, perfect in all its parts, and in shape a perfect sphere,46 that being the most perfect of all figures.

’ He (the Creator) assigned it that motion which was proper to its bodily form, that motion of all the seven which most belongs to reason and intelligence. Wherefore turning it about uniformly, in the same place, and in itself, he made it to revolve round and round; but all the other six motions he took away from it and stablished it without part in their wanderings.’47

’ And in the midst of it he put soul and spread it throughout the whole, and also wrapped the body with the same soul round about on the outside; and he made it a revolving sphere, a universe one and alone.’48

Here then we have all plurality of worlds denied and the one universe made to revolve uniformly, carrying with it in its revolution all that is within it, as in the Republic; the uniform revolution is of course the daily rotation. Turning ‘in itself’ means about its own axis and therefore, so to speak, coincidently with itself, so that one position does not overlap another, but in all positions the sphere occupies exactly the same space and place. The other ‘six motions’ from which it is entirely free are the three pairs of translatory motions, forward and backward, right and left, up and down.

Next Plato explains how the Creator made the Soul by first combining in one mixture Same, Other, and Essence, and then ordering the mixture according to the intervals of a musical scale, so that its harmony pervaded the whole substance. This substance, considered as having taken the form of a bar or band, a soul-strip as it were, he proceeds to divide.

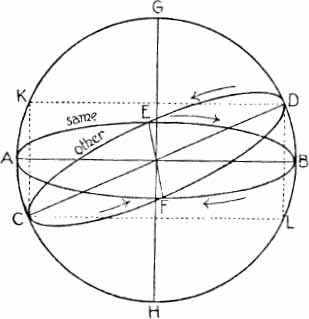

‘Next he cleft the structure so formed lengthwise into two halves and, laying them across one another, middle upon middle in the shape of the letter X, he bent them in a circle and joined them, making them meet themselves and each other at a point opposite to that of their original contact; and he comprehended them in that motion which revolves uniformly and in the same place, and one of the circles he made exterior and one interior. The exterior movement he named the movement of the Same, the interior the movement of the Other. The revolution of the circle of the Same he made to follow the side (of a rectangle) towards the right hand, that of the circle of the Other he made to follow the diagonal and towards the left hand, and he gave the mastery to the revolution of the Same and uniform, for he left that single and undivided; but the inner circle he cleft, by six divisions, into seven unequal circles in the proportion severally of the double and triple intervals, each being three in number; and he appointed that the circles should move in opposite senses, three at the same speed, and the other four differing in speed from the three and among themselves, yet moving in a due ratio’49

The two circles in two planes forming an angle and bisecting one another at the extremities of a diameter common to both circles are of course the equator and the zodiac or ecliptic. The equator is the circle of the Same, the ecliptic that of the Other. In the accompanying figure, AEBF is the circle of the Same (the equator), CFDE the circle of the Other (the ecliptic), and they intersect at the ends of their common diameter EF. GH is the axis of the universe which is at right angles to the plane of the circle AEBF. If we draw chords DK, CL parallel to the diameter AB common to the circles AEBF, AGBH, and join CK, DL, we have a rectangle of which KD is a side and CD is a diagonal. As the universe revolves round GH, each point on the circumference of the circle AGBH describes a circle parallel to the circle AEBF, i.e. a circle about a diameter parallel to AB or KD; that is, the revolution ‘follows the side’ KD of the rectangle. Similarly the revolution of the circle of the Other about an axis perpendicular to the plane of the circle CFDE ‘follows the diagonal’ CD of the rectangle.

Fig. 4.

The circle of the Same or the equator is the outer, and the circle of the Other, the ecliptic, is the inner. When Plato says that the Creator ‘comprehended them’ (i.e. both circles) in the motion of the Same, and then again later that he gave the supremacy to that circle, he means that the movement of that circle is common to the whole heaven and carries with it in its motion the smaller circles, the subdivisions of the circle of the Other, and everything in the universe; this he makes still clearer in a later passage where he speaks of the motion of the planets in the circle of the Other being ‘controlled’ by the motion of the Same, and the motion of the Same twisting all their circles into spirals.1 The subjection of all that is in the universe, including all the independent motions of the planets, to the one general movement of daily rotation is of course the same as we saw in the Republic; but there all the circles were in one plane, whereas the bodies moving in the opposite sense to the daily rotation here move in a different plane, that of the ecliptic, instead of that of the equator.

I have represented the directions of the motions in the two circles by arrows in the figure. The motion in the circle AEBF is in the direction represented by the order of the letters.

The statement of Plato that the Creator made the circle of the Same (i.e. the circle of the fixed stars) revolve towards the right hand and the circle of the Other (comprising the circles of the planets) towards the left hand has given the commentators, from Proclus downwards, much trouble to explain. It is also in contradiction to the observation in the Laws that motion to the right is motion towards the east,51 while the writer of the Epinomis again represents the independent movement of the sun, moon, and planets as being to the right and not to the left.2 There is of course no difficulty in the circumstance that Plato has previously said that the Creator took away from the world-sphere the six motions, up and down, right and left, forwards and backwards; for this refers to movements of translation such as take place inside the sphere, not to the revolution of the sphere itself. The axis of such revolution being once fixed, the revolution may be in one of two (and only two) directions;3 consequently there is nothing to prevent one of the two directions being described as to the right and the other as to the left. But why did Plato speak of the revolution from east to west as being motion to the right? Boeckh has discussed the question at great length, giving a full account of earlier views before stating his own.4 Martin’s explanation is that Plato is speaking from the point of view of a spectator looking south, as he would have to do in northern latitudes in order to see the apparent revolution of the sun from east to west; that is, the movement is from left to right. Boeckh, however, points out that the Greeks were accustomed, from the earliest times when diviners foretold events by watching the flight of birds, to turn their faces to the north; the east would therefore be on the right hand and would naturally be regarded as the most auspicious, and therefore as ‘right’ It is also true that the common view among the Greeks (we find it later in Aristotle5) would make of the sphere of the universe a sort of world-animal, which would have a right and left of its own, as it might be a man masked in a sphere put over him; and no doubt, on such a view, the east would be sure to be regarded as ‘right’ and the west as ‘left’ Boeckh therefore finds it difficult to believe that Plato could have represented the east as left. Assuming then that Plato regarded the east as right, Boeckh thinks Martin’s view untenable, and concludes that the only possible alternative is to suppose that Plato must have thought, in the Timaeus, of a movement from the right to the right again, i.e. of the whole revolution from east to east instead of the portion from the east to the west. But the movement, on the assumptions made, is undoubtedly left-wise, and it seems to me that Boeckh’s explanation is almost as violent as the desperate method of interpretation suggested by Proclus.1 Where Boeckh is in error is, I think, in supposing that Plato would identify the east in his world-sphere with the right hand at all; it seems to me that he could not possibly have done so consistently with the scientific attitude he adopted in denying the existence of any absolute up and down, right and left, forward and backward in the spherical universe. He explains, for example, that ‘up’ and ‘down’ have only a relative meaning as applied to different parts of the sphere,2 and it is clear that, in the same connexion, he would say the same of right and left. Now suppose that a particular point on the equator of the universe is east at a given moment; after about six hours the same point will be south, after six more west, and so on. The case then is similar to that put by Plato when he says that a man going round the circumference of a solid body placed at the centre of the universe would at some time arrive at the antipodes of an earlier position and would therefore, on the usual view of ‘up’and down, have to call ‘down’ what he had before described as ‘up’, and vice versa58 Plato would never, surely, have made the same mistake in speaking of the universe. On the contrary, when he spoke of the daily rotation, he properly ignored all question of a starting-point, whether east or west, right or left, or of the position of a person setting the sphere in motion, and confined himself to distinguishing by different names the two possible directions of motion in order to make it clear that the circles of the Same and of the Other moved in opposite directions. The expressions to the right and to the left were obviously well adapted to express the distinction, and it seems to me that the reason of Plato’s particular application of them is simply this. He considered that the circle of the Same must have the superior motion; but right is superior to left; he therefore described the revolution of the circle of the Same as being to the right, and the revolution of the circle of the Other as being to the left, for this sole reason, without regard to any other considerations, just as in the Republic he confines himself to saying that Clotho at intervals, with her right hand, helps to turn the outer whorl of the spindle, and so on,1 without saying anything about the actual directions in which the respective whorls revolve. On the other hand, when he says in the Laws that revolution from west to east is to the right and revolution from east to west is to the left, he is, as Boeckh properly observes, merely using popular language.

The cutting of the circle of the Other into seven concentric circles (including the original circumference as one of the seven) produces seven orbits in exactly the same way as the eight whorls in the Myth of Er give eight orbits, the difference being that the outermost circle of the Republic, the circle about which the sphere of the fixed stars moves, is not now in the same plane with the other seven, but is the circle of the Same in a different plane. Plato here says that the seven circles move in opposite directions, literally ‘in opposite senses to one another’, which, as there are only two directions, can only mean that a certain number of the seven revolve in one direction, and the rest in the other; we shall return later to this point, which presents great difficulty. The three which move at the same speed are of course the circles of the sun, Venus, and Mercury, as in the Republic, the same speed meaning, as there, not the same linear speed (as they are at different distances from the earth), but the same angular speed.

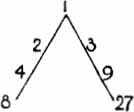

The seven circles are said to be ‘in the proportion of the double and triple intervals, three of each’. The allusion is to the Pythagorean ![]() represented in the annexed figure, the numbers on the one side after 1 being successive powers of 2 and those on the other side successive powers of 3. When the concentric circles into which the circle of the Other is divided are said to correspond to these numbers, it is clear that it must be the circumferences (or, what is the same thing in other words, the radii), not the areas, which so correspond; for, if it were the areas, the radii would not be commensurable with one another. The dictum is generally1 taken to mean that the radii of the successive orbits, i.e. the distances between the successive planets and the earth, are in the ratio of the numbers 1, 2, 3, 4, 8, 9, 27. But Chalcidius2 apparently takes the several numbers to indicate the successive differences between radii, for he says that, while the first distance (1) is that between the earth and the moon, the second (2) is the distance between the moon (not the earth) and the sun; on this view, the successive radii are 1, 1 + 2 = 3, 1+2 + 3 = 6, &c. Macrobius3 says that the Plato-nists made the distances cumulative by way of multiplication, the distance of the sun from the earth being thus (in terms of the distance of the moon from the earth) 1 × 2 or 2, that of Venus 1x2x3 = 6, that of Mercury 6 × 4 = 24, that of Mars 24 × 9 = 216, that of Jupiter 216 × 8 = 1,728, and that of Saturn 1,728 × 27 = 46,656. (It will be observed that in this arrangement 9 comes before 8, Macrobius having previously explained this order by saying that, after 1, we first take the first even number, 2, then the first odd number, 3, then the second even number, 4, then the second odd number, 9, then the third even number, 8, and last of all the third odd number, 27.) But, whatever the exact meaning, it is obvious that we have here no serious estimate of the relative distances of the sun, moon, and planets based on empirical data or observations; the statement is a piece of Plato’s ideal a priori astronomy, in accordance with his statement in the Republic, Book VII, that the true astronomer should ‘dispense with the starry heavens’.

represented in the annexed figure, the numbers on the one side after 1 being successive powers of 2 and those on the other side successive powers of 3. When the concentric circles into which the circle of the Other is divided are said to correspond to these numbers, it is clear that it must be the circumferences (or, what is the same thing in other words, the radii), not the areas, which so correspond; for, if it were the areas, the radii would not be commensurable with one another. The dictum is generally1 taken to mean that the radii of the successive orbits, i.e. the distances between the successive planets and the earth, are in the ratio of the numbers 1, 2, 3, 4, 8, 9, 27. But Chalcidius2 apparently takes the several numbers to indicate the successive differences between radii, for he says that, while the first distance (1) is that between the earth and the moon, the second (2) is the distance between the moon (not the earth) and the sun; on this view, the successive radii are 1, 1 + 2 = 3, 1+2 + 3 = 6, &c. Macrobius3 says that the Plato-nists made the distances cumulative by way of multiplication, the distance of the sun from the earth being thus (in terms of the distance of the moon from the earth) 1 × 2 or 2, that of Venus 1x2x3 = 6, that of Mercury 6 × 4 = 24, that of Mars 24 × 9 = 216, that of Jupiter 216 × 8 = 1,728, and that of Saturn 1,728 × 27 = 46,656. (It will be observed that in this arrangement 9 comes before 8, Macrobius having previously explained this order by saying that, after 1, we first take the first even number, 2, then the first odd number, 3, then the second even number, 4, then the second odd number, 9, then the third even number, 8, and last of all the third odd number, 27.) But, whatever the exact meaning, it is obvious that we have here no serious estimate of the relative distances of the sun, moon, and planets based on empirical data or observations; the statement is a piece of Plato’s ideal a priori astronomy, in accordance with his statement in the Republic, Book VII, that the true astronomer should ‘dispense with the starry heavens’.

Fig. 5.

Plato goes on to the question of Time and its measurement. As the ideal after which the world was created is eternal, but no created thing can be eternal, God devised for the world an image of abiding eternity ‘moving according to number, even that which we have named time’.

‘For, whereas days and nights and months and years were not before the heaven was created, he then devised their birth along with the construction of the heaven. Now these are all portions of time. . .’1

‘So, then, this was the plan and intent of God for the birth of time; the sun, the moon, and the five other stars which are called planets have been created for defining and preserving the numbers of time.