and who therefore ran through the icy streets obsessed with a sudden flash of the alchemy of the use of the ellipsis the catalog the meter & the vibrating plane,

who dreamt and made incarnate gaps in Time & Space through images juxtaposed, and trapped the archangel of the soul between 2 visual images

—Allen Ginsberg2

This book has been a study of the creative uses of fragmentation in art and literature, and an examination of the workings of collage across different media, showing how diverse practitioners of collage could be whilst sharing many of the same influences. As such, I was keen that the main subjects of my study embody this practice, and be themselves relatively divergent, using different techniques, and moving in largely unrelated social and creative circles. This priority, as well as more practical concerns about the length of this book, led me to occlude several figures who also worked in collage or the collage-esque during this period and who had close links with New York City, two of whom – Allen Ginsberg and John Ashbery – I will discuss in more detail below. Of course, as Pierre Joris asserts, ‘there isn’t a 20th century art that was not touched, rethought or merely revamped by the use of [collage]’,3 and so a degree of arbitrariness in my choice of subjects was inevitable. Brandon Taylor’s observation that ‘collage looms large enough in the annals of the New York scene to underscore virtually every achievement of note’,4 further confirms this.

Robert Rauschenberg (‘the trashcan laureate’5), Jasper Johns, Franz Kline, Willem de Kooning, Lee Krasner, Ann Ryan, and Larry Rivers were among the New York-based artists who carried collage forward through the 1950s and on into the 1960s, helping to buoy it up in the engulfing waters of Abstract Expressionism and Pop Art, and, as had happened previously in Europe, to enable it to extend productively into other disciplines. Whilst Gregory Ulmer is correct to suggest that collage had lost some of its revolutionary sheen by the 1960s,6 this did not prevent it from continuing to flourish, and many artists, most notably Joe Brainard, Jess, and Romare Bearden, worked successfully in collage until late in the twentieth century. The idiosyncratic Brainard, ‘painter among poets’,7 distanced himself from the seriousness and machismo of the New York art scene, and popularised the comic-strip cartoon as a collaborative medium. His delicate, intelligent, labour-intensive collages require engagement from and exchange with the viewer, and significantly, as Jenni Quilter notes, in Brainard’s work ‘error is seen as a trace of development rather than an imperfection’.8 Jeff Koons, John Ashbery, Rosemary Karuga, Star Black, and Wangechi Mutu continue to work in collage. John Cage and Morton Feldman developed collage musically, Cage relishing particularly the validation of everyday minutiae: ‘beauty is now underfoot wherever we take the trouble to look’.9 In addition to Bob Dylan’s trans-location of the blues and employment of collage techniques in his songwriting, George Martin and the Beatles spliced up tape, and David Bowie used the cut-up method to write lyrics, a practice which later influenced Thom Yorke and Kurt Cobain. Julio Cortázar used collage and cut-ups to write his ‘counter-novel’, Hopscotch (1963), whilst Allen Ginsberg also realised, as the quotation above indicates, the potency of ‘images juxtaposed’ and the facility, offered by collage, for processing and presenting real information.

Collage represented, for Ginsberg, a means of getting close to and of recreating the human consciousness. It also enabled him to find an appropriate tone in which to articulate his prophetic politics: asked about The Fall of America: Poems of These States (1973), he commented that the collection’s purpose was ‘to cover like a collage a lone consciousness travelling through these states during the Vietnam War’.10 Indebted to Pound and to William Carlos Williams, Ginsberg felt that a poem could be

a collage of the simultaneous data of the actual sensory situation [which] the very nature of the composition ties … together. You don’t really have to have a beginning, middle, and end – all they have to do is register the contents of one consciousness during the time period.11

This approach is evident in poems such as ‘Wichita Vortex Sutra’, in which auditory phenomena, such as snippets from the radio (‘you certainly smell good’) and visual images (‘Turn Right Next Corner / The Biggest Little Town in Kansas’), recorded as Ginsberg saw them, are juxtaposed with imaginary scenes (‘When a woman’s heart bursts in Waterville / a woman screams equal in Hanoi’).12 It is also manifest in Howl’s sequence of surreally juxtaposed collage-esque vignettes, whose dizzying visual, temporal, and syntactical shifts, which make up the fabric of much of the poem, give it a dynamic collage texture. This is fundamental to Howl’s strikingly performative nature: it extends beyond the poet and demands that the reader bear witness to the metamorphic collage actions of the ‘angelheaded hipsters’ and listen to the poet’s attempts ‘to recreate the syntax and measure of poor human prose’, thus coercing a quasi-political engagement with the poem, not just as a reader of the catalogue of insanity, but also as a viewer of the succession of apocalyptic scenes, and an active listener to the poet’s howl.13

When John Ashbery made his debut as a professional artist at the age of eighty-one, exhibiting a collection of collages at the Tibor de Nagy Gallery in New York in September 2008, he confessed that he ‘did the collages for amusement, without thinking anyone else would see them or be interested’.14 In one sense, this remark is a testament to Ashbery’s modesty and understatedness as an artist, but there is also more to it than that. As a poet, Ashbery has always seemed more interested in the process of writing poetry than in the poetry itself – his own work, as he said of Frank O’Hara’s, is also the ‘chronicle of the creative act that produced it’.15 Furthermore, Ashbery’s collages make clear his artistic debt to Joe Brainard, in whose work, as noted above, ‘error is [always] seen as a trace of development rather than an imperfection’.16 Far from being artworks which would never be seen or in which no one would be interested, Ashbery’s collages, like his poems, are simultaneously an aesthetic end in themselves, and also a creative process laid bare.

Collage is something that Ashbery does, regularly, and has always done, in a sense, in his poetry. To borrow from John Yau, ‘if … you didn’t suspect that [Ashbery] might be a man with a pair of scissors (along with Max Ernst, Andre Breton, Joseph Cornell, and his friend Joe Brainard), then you probably haven’t read a single thing he has written’.17 For Ashbery, collage is more than just a crucial part of his creative process: it is almost a way of life. He is an ‘enthusiast who gets excited by all manner of things, from the loftiest realms of high culture to the weirdest currents of popular culture’.18 Collage enables him to present ideas or concepts whilst resisting grandeur – he values its accessibility and democracy, its ability to keep secrets, drop hints, and provoke discussions, to play with time, and to be simultaneously the simple souvenirs of a life and also compelling works of art. Physically, his visual collages enable him to embody the pluralism he has manifested throughout his oeuvre, as well as ‘the fated nature of encounter’,19 to quote Geoff Ward, with which Ashbery has always been fascinated.

Although the 2008 exhibition was Ashbery’s first solo show, two of the collages shown dated back to the late 1940s, having been made when he was still a student at Harvard. As well as several pieces created with the event in mind, the exhibition also featured work dating from the 1970s, which had only been recently rediscovered. The bulk of this was made at Joe Brainard’s house in Vermont, where, Ashbery recalls, ‘after dinner we got in the habit of sitting around and cutting up old magazines and making collages’. Not only are several collages dedicated to Brainard, but they are, in fact, made up of old postcards and cut-out things which he had sent to Ashbery over the years.

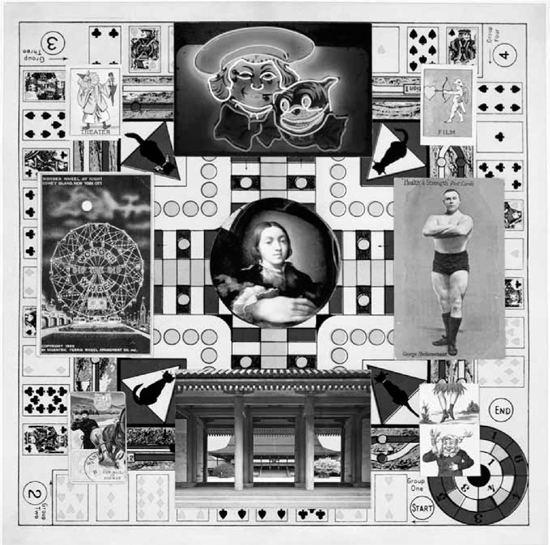

Given the wide temporal scope of Ashbery’s first exhibition, the collages displayed differed widely in terms of their content, but their style – and indeed that of the collages he has made since – possessed the same inventiveness, eclecticism, and lightness of touch which characterises his poetry. His influences as an artist and writer emerge almost as a collage in their own right: images of birds and children, superheroes and cities, Renaissance figures and cartoons encounter each other in media ranging from postcards to board games to simple scraps of paper, with the legacies of Picasso, Ernst, Schwitters, Cornell, Anne Ryan, and Brainard all in evidence. In particular, as Dan Chiasson observed in the New York Review of Books in 2009, ‘Ashbery is spiritual cousin to Joseph Cornell, the great collector of clay pipes, pill boxes, and girls’ dolls, and to the outsider artist Henry Darger, whose homemade cosmology, brilliantly embellished in watercolor and collage, influenced Ashbery’s 1999 book Girls on the Run’.20 Many of the collages are compellingly seamless in their composition, forcing the viewer to peer closely in order to establish the nature of the almost invisible fissures. In his juxtaposition of figures, often children, with disquieting grounds, Ashbery succeeds in evoking a kind of time-limited innocence, in which lurks the devastation and excitement of incipient knowledge.

Ashbery exhibited further collages with Tibor de Nagy in 2011. In 2013, the Loretta Howard Gallery put on an exhibition entitled John Ashbery Collects: Poet Among Things, which invited viewers to experience the ‘living collage’21 which is Ashbery’s house in Hudson, New York. Embellishing the gallery walls with trompe-l’oeil paintings of doorframes and windowsills, and even a grand piano, curators Adam Fitzgerald and Emily Skillings made public a version of Ashbery’s art-filled home, displaying pieces of vintage bric-a-brac, ceramic pots, sheet music, a flier of Sylvester the Cat speaking French, various well-loved books by Ronald Firbank, Henry James and Gertrude Stein, among others, and, of course, selected pieces from Ashbery’s art collection, including work by Joe Brainard, Jane Freilicher, Alex Katz, Joseph Cornell, Willem and Elaine de Kooning, Joan Mitchell, Fairfield Porter, and Henry Darger. To call this an ‘art collection’, however, is to mislabel it as something far more cold and pecuniary than it is – many of these artists were or are Ashbery’s friends, and as Holland Cotter observed, in his review of the show for the New York Times, ‘it’s a comfort, really, to know that, once the show’s over, they’ll be returning home, to resume their roles in an art-filled life that has been so much, and so movingly, of a piece’.22 These items are less a collection, then, than a public presentation of a private life, in keeping with Ashbery’s poetry, which succeeds in being simultaneously secret and well-known, incomprehensible and democratic.

Ashbery has written articulately and persuasively about numerous collagists, including Anne Ryan, E.V. Lucas and George Morrow, Max Ernst, and Kurt Schwitters, and his sustained interest in the collage process is evident in much of his poetry. His most notable and successful use of poetic collage is in his highly experimental, oppositional collection The Tennis Court Oath, published in 1962. The Tennis Court Oath was met with disapproval even by Ashbery’s admirers, including Helen Vendler, who views it as an unsuccessful ‘mixture of wilful flashiness and sentimentality’, Marjorie Perloff, who finds the poems to be ‘excessively discrete’, and Harold Bloom, who argues that Ashbery ‘attempted too massive a swerve away from the ruminative continuities of Stevens and Whitman’.23 Certainly, the collection can be troubling, difficult, and obscure, but the poems are powerful in their raw experimentalism, and their embrace of an Emersonian state of flux and an alternative interpretation of what it means to be avant-garde. As Frank O’Hara announced, having apparently found himself brought almost to hysteria by it, it is ‘a work of desperate genius’.24 The poems in The Tennis Court Oath subvert readerly expectations of poetry, demanding, in their ellipses, missing words, swift transitions, disjunctive syntax, partial erasure and illogical constructions, that the reader find ways of understanding his work other than straightforward or traditional critical analysis, eschewing New Critical-style ‘symbol-hunting’.25 In a 1983 interview with Paris Review, Ashbery recalled the process of publishing The Tennis Court Oath:

I didn’t expect to have a second book published, ever. The opportunity came about very suddenly, and when it did I simply sent what I had been doing. But I never expected these poems to see the light of day. I felt at that time that I needed a change in the way I was writing, so I was kind of fooling around and trying to do something I hadn’t done before.26

Many of the poems in the collection, then, are chronicles of their own creative acts, and Ashbery seems to ask that the reader of his work give precedence to the same principle to which he adheres as a writer – namely, to value the processes of reading and attempting to understand over any definitive answers that the poetry may or may not yield. The collection also, despite manifest associations with avant-garde art techniques, succeeds in situating itself at a remove from the movements – including Dada, Surrealism and Abstract Expressionism – which generated them. Harold Bloom lamented that the collection was an exercise in ‘calculated incoherence’,27 but imaginatively the poetry is relatively straightforward, if one is prepared to accept ‘that the imagination is not an inward quality in search of expression, but, rather, an event that occurs when perception contacts the world with the force of desire in the form of words or paint or sounds’.28

The collection, whose unique meditative qualities are merged with noticeable affinities with Duchamp’s readymades and found objects, and with the deliberate erasure practised by Jasper Johns, Robert Rauschenberg, and Willem de Kooning, requires that the reader actively contribute to the poetry in a non-traditional way. Given the absence of any internal explanation on Ashbery’s part, and the use, throughout the text, of the word ‘I’ as a verbal found object rather than as an expression of character or direct opinion, the reader must provide their own flexible interpretations of the work, taking into account the significance of ellipses, the poetry’s auditory qualities, and the possibilities engendered by the fissures which run throughout the text. As in his visual collages, the collection’s success is in its ‘distribution of the elements of discontinuity so that they are just held in balance, or framed, by the fewest necessary cohesive elements’.29

Ashbery’s view on Surrealism fell in line with that of Henri Michaux, the painter and poet whom he interviewed in 1961, who observed that the movement gave to writers and artists ‘la grande permission’. In other words, as Ashbery wrote, its significance lay in ‘the permission [the Surrealists] gave everybody to write whatever comes into their heads’.30 Notwithstanding, he maintained a certain distance from the European avant-garde, downplaying its influence on his work, primarily because, as David Sweet suggests, ‘to be avant-garde in the wake of the radical Avant-Garde is to have a kind of perverse recourse to tradition, illusionism, and obsolete form’.31 Ashbery also pointed out that

What has in fact happened is that Surrealism has become a part of our daily lives: its effects can be seen everywhere, in the work of artists and writers who have no connection with the movement, in movies, interior decoration, and popular speech. A degradation? Perhaps. But it is difficult to impose limitations on the unconscious, which has a habit of turning up in unlikely places.32

Sweet suggests that Ashbery, in the 1960s, sought a new ‘true Avant-Garde’ which ‘only properly exists in a condition of cultural tenuousness: unconsolidated and largely unrecognized’.33 His observation chimes with Ashbery’s own disparaging remarks about Grove Press’s exhortations on subway posters to ‘join the “Underground generation” as though this were as simple a matter as joining the Pepsi generation’.34 The Tennis Court Oath embodies Ashbery’s refusal to ascribe fixed meanings to his poems, and thereby place limitations on the unconscious, either his own or that of his readers; and as such the collection is a model of an uncircumscribed avant-garde poetic.

The second poem in the collection, ‘They Dream Only of America’, exemplifies Ashbery’s use of collage in The Tennis Court Oath, and also, in direct relation to this, the sense that Andrew Epstein has of Ashbery as ‘a pragmatist, tolerant of infinitely multiple perspectives, who sees life as an often baffling struggle with randomness and contingency, where human experience consists of limited and always provisional attempts to cope with and adjust to changing circumstances’.35 Like Bob Dylan’s ‘Tangled Up in Blue’, and Ginsberg’s Howl and ‘Wichita Vortex Sutra’, this poem is both a multi-layered assemblage of stories and a quasi-nomadic collage of America. Its illusions, misrepresentations, disguises, temporal shifts, and unstable roles invite a multiplicity of interpretations. Some read it as a tale of two gay fugitives waiting ‘for our liberation’,36 others as a Twain-esque murderer and child ‘hiding from darkness in barns’;37 it could even be read as a more conventional Beat-style trip taken by a pair of lovers. Of course, even if one accepts the possibility of these multiple narratives, one is still circumscribing oneself within the limitations of chronological story-telling, which this poem, in its unstable, mercurial lyricism seems to be striving to undermine. As Ashbery remarked in the Paris Review interview:

Things are in a continual state of motion and evolution, and if we come to a point where we say, with certitude, right here, this is the end of the universe, then of course we must deal with everything that goes on after that, whereas ambiguity seems to take further developments into account.38

‘They Dream Only of America’ begins with an unidentified personal pronoun (‘They dream only of America’), which is repeated in the second stanza (‘They can be grownups now’), before transitioning into an also unidentified ‘he’, which then segues into ‘we’, then ‘I’, and, finally, ‘you’. The collaging of multiple identities in this way prevents the reader from interpretively using the numerous poetic symbols which, self-reflexively, punctuate the poem (‘Was the cigar a sign? / And what about the key?’). The poem advocates a suspicion of symbols, highlighting the worthlessness of symbolism for symbolism’s sake, and illustrating the futility of a symbol if we cannot tell to whom or to what it refers. David Herd points out that Ashbery goes so far as to suggest that an uninhibited fondness for symbols may even be dangerous, noting that the ‘delicious’ honey ‘burns the throat’, that the carefree drive ‘at night through dandelions’ causes a headache, and that the final seduction by ‘cigar’ and ‘key’ results in a broken leg:

Whenever the speaker seems to be growing too fond of signs and symbols – at each point at which they seem in danger of preoccupying him – he receives a painful reminder that such fondness is inappropriate, dangerous even, insofar as it causes one to neglect the reality of the situation.39

However, the fact that the poem is full of discontinuously employed poetic symbols, that rear incongruously up out of the collage syntax, indicates that Ashbery both acknowledges and understands our love of and need for them, as well as his own, both in poetry and in life. He knows what it is to ‘care only about signs’, and seems to suggest, in the lines – ‘There is nothing to do/For our liberation, except wait in the horror of it’ – an awareness that the writing and reading of this new, oppositional kind of poetry is difficult and painful, but that it requires patience and a willingness to absorb rather than methodically collect meanings. The uncertainty and discontinuity in the poem, expedited by the collage form and manifested in broken syntax, rejection of metaphor, demarcated fragments of speech, and incongruous adverbs, prevents rhythm from building, or acceleration from taking place Although the words in the poem unilaterally indicate flight either to or from something undefined, ultimately the poem itself, detached from verbal meanings, embodies an impulse to pause and wait. This is typical of Ashbery’s larger preoccupation with the relationship between stasis and motion: after all, he ends his poem ‘The Bungalows’, from The Double Dream of Spring, with the lines:

For standing still means death, and life is moving on,

Moving on towards death. But sometimes standing still is also life.40

Ashbery seems, in ‘They Dream Only of America’, in The Tennis Court Oath, and in his visual collages, to be attempting to combine together the ‘self-abnegating’41 creative methods of Surrealism with the ruminative styles of Baudelaire, Eliot, or even Joseph Cornell, in which fleeting intersections create constellations of imagery which can, but are not necessarily required to represent anything beyond themselves. In spite of the affiliations of his poetry to Dada and Surrealism, Ashbery rejects his role as the successor of an avant-garde which had been undone by its own success, and which had, as a result, become mainstream; instead he creates his own avant-garde, which may be ‘unconsolidated and largely unrecognized’,42 which may run the gamut of being labelled calculatedly incoherent, but whose main achievement is to resist solitary posturing, didacticism, and the urge to provide a definitive poetic or aesthetic statement. As Ashbery remarked in ‘The Invisible Avant-Garde’, published in ARTnews in 1968, ‘artists are no fun once they have been discovered’.43

Fig. C.1 John Ashbery. The Mail in Norway, 2009. Collage, digitized print, 16 ¼ × 16 ¼ inches. Courtesy Tibor de Nagy, New York.

Alfred Leslie asserted that his 1964 film, The Last Clean Shirt, should provoke the question: ‘“What the fuck is going on?”’ because, ‘to most people, reality is nothing more than a confirmation of their expectations’.44 Expectations of collage are that it is strictly flat, one-dimensional, and limited to the realm of plastic art, but the reality is quite different, often provoking, on the part of the viewer, reader or listener, precisely Leslie’s question. This is its fundamental appeal: in and of itself, it subverts expectations and alters our perception of reality. I began this book by showing that the tendency to circumscribe the art of collage within the limited sphere of cut-and-paste is misleading. Collage is a practice which demands a multiplicity of approaches: to delineate it stringently as either one thing or another is to severely limit our understanding of the work of the artists, writers, and musicians who came to use it in a non-traditional way. In part, this is the reason for the lack of attention thus far devoted to collage in the work of Joseph Cornell, William Burroughs, Frank O’Hara, and Bob Dylan. It is also why, in spite of the considerable amount of existing scholarship on collage as a plastic art form, relatively little work has been carried out relating to the interdisciplinary aspects of the practice. However, as I hope I have illustrated, a view of collage that is as open and adaptable as the collage practice itself, enables the critic not only to appreciate the multiple ways in which it operates as an art form, but to also insert into its history individuals who might not otherwise have taken up their place there.

For Cornell, Burroughs, O’Hara, and Dylan, as for many other twentieth-century artists, writers, and musicians from Picasso to Ashbery to Bowie, in spite of their very different personalities and creative output, encountering collage had a catalytic effect, enabling each to overcome a crisis in representation that threatened to destabilize their work. Cornell, who felt convinced that he was an artist and yet was hampered by his inability to draw or paint, used collage to gain access to the art world and to show what he was capable of creating given the right medium. For Burroughs, his formal, organisational problems with linear composition were turned to his advantage by his use of collage, which enabled him to move beyond requirements for narrative and chronology; collage is also a key tool for readers approaching his cut-up novels. For O’Hara, collage provided a means of writing poetry that navigated an effective path between plastic art and literature, enabling him to choose the facets of each which best suited his compositional style and what he wanted to say. Dylan was able to use collage to uniquely enunciate his brand of social commentary whilst also succeeding in discovering new possibilities within a genre that apparently had no more to give.

Part of the problem with existing work on collage in Cornell, Burroughs, O’Hara, and Dylan is that it fails to situate them within the wider context of the evolution of twentieth-century collage, tending to treat their uses of collage in isolation, which limits its impact and has the effect of blinkering the reader’s understanding of what they were doing and why it was important. Collage changed not just the ways in which art is made, but also the ways in which viewers approach art, giving them a newly subjective and interactive role to play, and simultaneously abolishing the notion of a single approach or solution to any given piece of art, writing, or music. It had a similar effect on literature, changing the reading experience by allowing the author to abdicate his or her role as absolute arbiter of meaning, making the process of reading and interpreting more fluid, more subjective, more experiential, and bringing it closer to art. Collage can be seen as both an assault on the reader or viewer, and as an invitation to participate in the artwork or text’s plastic or conceptual processes. Either way, it is an invitation to engage, rather than to look or to read in passivity. Whilst historically the pasting to paper of miscellaneous items is, of course, a key part of the collage practice, it evolved, from 1912, to encompass the artist or writer or musician’s emotional and intellectual relationship with their aesthetic universe, which includes not just whatever it is that constitutes their work, but also the individuals who will, collectively, come to interpret it, and to whom, as a result, a ‘new thought’ is yielded.45

1 Emerson, ‘The Poet’, 463.

2 Ginsberg, Howl, in Collected Poems 1947–1997 (New York: HarperCollins, 2006), 138.

3 Joris, 86.

4 Taylor, 106.

5 Jonathan Jones, ‘The Trashcan Laureate’, Guardian, 15 May 2008, 23.

6 Ulmer, 409.

7 Richard Deming, ‘Everyday Devotions: The Art of Joe Brainard’, Yale University Art Gallery Bulletin (2008): 82.

8 Quilter, ‘The Love of Looking: Collaborations between Artists and Writers’, in Painters and Poets: Tibor de Nagy Gallery (New York: Tibor de Nagy, 2011), 78.

9 Cage, ‘On Robert Rauschenberg, Artist and His Work’, from Silence: Lectures and Writings, 98.

10 Quoted in Michael Andre, ‘Levertov, Creeley, Wright, Auden, Ginsberg, Corso, Dickey: Essays and Interviews with Contemporary American Poets’, unpublished doctoral dissertation (Columbia University, 1974), 146. (Source: Fred Moramarco, ‘Moloch’s Poet: A Retrospective Look At Allen Ginsberg’s Poetry’, in American Poetry Review 11, no. 5 (September/October 1982): 10–14, 16–18.

11 Ginsberg, ‘Improvised Poetics’, in Composed on the Tongue, ed. Donald Allen (Bolinas: Grey Fox, 1980), 26–7.

12 Ginsberg, ‘Wichita Vortex Sutra’, Collected Poems, 402–19.

13 Quotations are from Howl, in Collected Poems, 134 and 138.

14 Ashbery, quoted in Holland Cotter, ‘The Poetry of Scissors and Glue’, New York Times, 8 September 2008, http://www.nytimes.com/2008/09/14/arts/design/14cott.html [Accessed 20 June 2012].

15 Ashbery, Introduction to The Collected Poems of Frank O’Hara, viii-ix.

16 Quilter, 78.

17 John Yau, ‘John Ashbery: Collages: They Knew What They Wanted’, The Brooklyn Rail, 10 October 2008.

18 Ibid.

19 Geoff Ward, Statutes of Liberty: The New York School of Poetry (New York: St Martin’s Press, 1993), 160.

20 Dan Chiasson, ‘John Ashbery: “Look, Gesture, Hearsay”’, New York Review of Books, 9 April 2009.

21 Adam Fitzgerald, ‘Right at Home: On John Ashbery’s Hudson House and Its Collections’, in John Ashbery Collects: Poet Among Things (online exhibition catalogue), 10–18, http://issuu.com/lorettahoward/docs/ashbery_pages_pages_issufinal [Accessed 15 April 2014].

22 Holland Cotter, ‘John Ashbery Collects’: ‘Poet Among Things’, New York Times, 25 October 2013.

23 Helen Vendler, ‘Understanding Ashbery’, The New Yorker (16 March 1981), 114–36; Marjorie Perloff, ‘Fragments of a Buried Life’, in Lehman, Beyond Amazement: New Essays on John Ashbery (Ithaca and London: Cornell University Press, 1980), 78; Harold Bloom, John Ashbery (New York: Chelsea House, 1985), 50.

24 Frank O’Hara (9 March 1962), quoted in Epstein, Beautiful Enemies, 241.

25 Lehman, 157.

26 John Ashbery, ‘The Art of Poetry No. 33’, interviewed by Peter A. Stitt, Paris Review 90 (Winter 1983), 30–60.

27 Harold Bloom, ‘The Charity of the Hard Moments’, in John Ashbery, ed. Harold Bloom (New York: Chelsea House, 1985), 53.

28 Donald Revell, ‘Purists Will Object: Some Meditations on Influence’, in The Tribe of John: Ashbery and Contemporary Poetry, ed. Susan Schultz (Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1995), 91–100.

29 David Shapiro, John Ashbery: An Introduction to the Poetry (New York: Columbia University Press, 1979), 61.

30 Ashbery, Reported Sightings, 398.

31 David Sweet, ‘“And Ut Pictura Poesis Is Her Name”: John Ashbery, the Plastic Arts, and the Avant-Garde’, Comparative Literature 50, no. 4 (Autumn 1998): 319.

32 Ashbery, ‘In the Surrealist Tradition’, Reported Sightings, 4.

33 Sweet, 230.

34 Ashbery, ‘Writers and Issues: Frank O’Hara’s Question’, 81.

35 Epstein, Beautiful Enemies, 133.

36 John Shoptaw, On the Outside Looking Out (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1994), 65–6.

37 Alan Williamson, Introspection and Contemporary Poetry (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1984), 121–2.

38 Ashbery, ‘The Art of Poetry’ (No. 33), Paris Review 90 (Winter 1983), 46.

39 David Herd, John Ashbery and American Poetry (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2000), 85.

40 John Ashbery, ‘The Bungalows’, from The Double Dream of Spring (New York: Dutton, 1970).

41 Sweet, 325.

42 Sweet, 320.

43 John Ashbery, ‘The Invisible Avant-Garde’, ARTnews Annual, October 1968.

44 Quoted in Daniel Kane, We Saw the Light: Conversations between the New American Cinema and Poetry (Iowa City: Iowa University Press, 2009), 96.

45 Emerson, ‘The Poet’, 463.